In June, the leaders of the G7 countries, meeting at a three day summit in Cornwall, issued a strongly worded statement demanding that China “respect human rights and fundamental freedoms, especially in relation to Xinjiang” and Hong Kong.1 The backers of Israel’s murderous assaults on Gaza and Saudi Arabia’s bloody war against the people of Yemen have no right to accuse anyone of human rights abuses, and the real concerns of these hypocrites soon became clear. China’s rising economic power presents “challenging non-market policies and practices which undermine the fair and transparent operation of the global economy”. As a communique at the subsequent NATO meeting in Brussels made clear, China is seen as a strategic competitor whose “stated ambitions and assertive behaviour present systemic challenges to the rules-based international order”.2

China’s rise has made it a serious competitor to the interests of the West’s ruling classes, and if the rules of your “rules-based” order are not enough, then they need to be bent a little. Donald Trump took the lead, imposing a set of tariffs on Chinese goods in 2018, and then banning Chinese tech companies Huawei and ZTE from United States government contracts. Despite major differences in other areas, his successor, Joe Biden, has maintained this confrontational stance towards China.3

Xinjiang and the plight of the region’s Muslim Uyghur population, along with the suppression of democracy in Hong Kong, are invoked to give a high-minded gloss to measures that are really about trying to protect the dominance of Western corporations. This newly discovered concern for the Uyghurs has led to allegations that a million or more of them—at least a tenth of their total population—are incarcerated in labour camps. China has also been accused of genocide.

How should the left respond to all this? Predictably enough Keir Starmer’s Labour have uncritically accepted the accusations and urged sanctions on China. However, there are also those on the left who, taking China’s side, try to excuse the repression that undoubtedly does take place. For instance, in October last year, the US-based Monthly Review journal hosted a report by the Qiao Collective, a group that “willfully ignores domestic repression of political dissidents in China” according to one Taiwanese activist.4

Others have taken more creditable positions. Critical China Scholars, a group based in the US that has opposed both US propaganda against China and racism against American Asians, issued an open letter criticising both the Qiao Collective’s report and Monthly Review for hosting it.5 This article attempts to outline a similar position, based on Marxist understandings of imperialism and national liberation, that supports Uyghur self-determination while opposing co-option of their cause by US imperialism and its British junior partner.

The evidence

Where does the often quoted figure of one million detainees come from? Jessica Batke, senior editor at the ChinaFile website, suggests that there are two key sources.6 One is a Washington-based non-governmental organisation, Chinese Human Rights Defenders, whose figure is extrapolated from interviews with just eight Uyghurs asked to estimate the number detained in their villages.

The other source is Adrian Zenz, whose findings have been widely drawn on by the mainstream media. He describes himself as an “independent researcher”, but, as a born again Christian, Zenz reports to a higher authority. He claims he feels “very clearly led by God” to investigate Xinjiang, though he admits he is no specialist on the area.7 He is also a senior fellow at the rabidly anti-communist Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation. This organisation has form when it comes to providing conveniently round numbers as soundbites. It claims that communism is responsible for a “holocaust” of 100 million victims globally, a figure repeated by Donald Trump when still president. Like Trump it also blames China for the coronavirus pandemic.8

The claims of Zenz have been amplified by “think-tanks” aligned with the US establishment. For instance, another of his reports, “Coercive Labor in Xinjiang”, is published by Newlines Institute, an organisation that claims to be a “non-partisan think-tank” but actually has close ties to the US military.9 Its parent organisation, Fairfax University of America, was nearly shut down by regulators in 2019 for plagiarism and providing “patently deficient” education.10

Another feature of the “evidence” is the use of aerial photographs, a technique surely discredited by the Iraq war.11 There is clearly a wide margin of error in assumptions about the purposes of institutions identified in these images and estimates of their capacities, let alone their actual populations. A report by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) implicitly acknowledges this, stating that estimates of the number of re-education camps in Xinjiang range from 181 by Agence France-Presse to 1,200 by our friend Zenz.12 ASPI is another “independent, non-partisan think-tank” that is a little shy about its connections—fully 85 percent of its funding comes from the Australian, US and UK governments.13

The Chinese government provides no figures for camp inmates, so estimates are inevitably based on supposition and guesswork, unsurprisingly varying widely. Political scientist Sean Roberts, for instance, quotes figures of 100,000, 500,000 and 800,000 from different sources.14 Nevertheless, organisations close to the US government, such as the various think-tanks and Radio Free Asia, take the highest figures and most sensational stories and promote them. These are then adopted uncritically by more widely respected organisations such as the BBC and Human Rights Watch, helping to create a consensus that supports the US’s agenda.15

Both the Trump and Biden administrations have used propaganda from such dubious sources to label China’s treatment of the Uyghurs as “genocide”. This seems deliberately designed to imply that something akin to the Nazi Holocaust is taking place, something worse than human rights violations being committed elsewhere. It is not a word, for instance, that they would ever apply to Palestine, despite Israel’s well-documented crimes.

The self-serving and opportunist nature of US “support” for the Uyghurs is shown by its earlier accommodation with China’s attempt to hitch its repression of the Uyghurs to the newly declared global “War on Terror”. In a sordid piece of political horse trading, the US complied with demands for the East Turkestan Independence Movement (ETIM) to be condemned as terrorist in order to get Chinese acquiescence in the war on Iraq. ETIM remains on the terrorist list despite apparently only ever having been a figment of the Chinese government’s imagination.16 The US also incarcerated 22 Uyghurs in Guantanamo Bay in 2002. Despite the US later admitting they should never have been detained, the last of them were only released in 2013.17

However, this does not mean that the left should take a “my enemy’s enemy is my friend” attitude and become apologists for the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The Qiao Collective are rightly “skeptical that the US—having engaged in two decades of perpetual war in Muslim-majority nations—has any legitimate moral interest or grounds on which to defend Muslim religious rights in Xinjiang.” Yet, having stated that “there are aspects of PRC policy in Xinjiang to critique”, the Qiao Collective instead try to justify China’s actions in terms borrowed from the “War on Terror”, offering no criticism whatsoever.18

It is unnecessary to accept all the claims made by supporters of US imperialism in order to recognise the abundant evidence of the Chinese state’s oppression of the Uyghurs, and that it has taken a decided turn for the worse in recent years. In fact oppression and exploitation of national minorities was built into the Communist Party’s nation-building programme from the start.

The Communist Party and China’s minorities

Although people who are not Han Chinese make up only around eight percent of the population, they occupy a much larger proportion of the country’s land.19 Thus, relations with these groups was an important consideration for the early Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Initially they followed the Bolsheviks, who at the time of the 1917 Russian Revolution supported the right of self-determination of minority peoples, including the right to secede and form independent states.

The point was to break Russian workers from the chauvinism of their own rulers. Thus, it was not “a demand for separation, fragmentation and the formation of small states’’, but an “expression of struggle against all national oppression”.20 To do otherwise would “play into the hands” of “the absolutism of the oppressor nation”.21 The right of secession was crucial because it made the oppressed peoples agents of their own destiny. Anything less would hand the initiative to the dominant power.

A resolution of 1930 declared that “the toiling masses” of those areas where the non-Chinese population was in the majority “have the right to determine by themselves whether they want to secede from the Chinese Soviet Republic and form their own independent state”.22 However, “from the moment they included Lenin’s principle of national self-determination in the party’s political program, CCP leaders attempted to circumscribe it”.23 By the time they came to power this about turn was complete and it was officially stated that no region could secede.24 This reflected the essentially nationalist nature of the 1949 Revolution.

This new nation, Mao Zedong explained, “is a country vast in territory, rich in resources and large in population; although, as a matter of fact, it is the Han nationality whose population is large and the minority nationalities whose territory is vast and whose resources are rich.” When Mao said this, he was polemicising against Han chauvinism. Unfortunately, this was a pragmatic rather than a principled position, as became clear. Mao set out his logic: “No material factor can be exploited and utilised without the human factor. We must foster good relations between the Han nationality and the minority nationalities…in order to build our great socialist motherland”.25 Winning the hearts and minds of the minorities would allow the state to exploit their resources.

Chinese Communist theories on the national question drew on Stalin’s formula of a nation as “a historically formed stable community of people arising on the basis of common language, common territory, common economic life and a typical cast of mind manifested in a common culture”.26 Although too rigid to be applied without modification, by rejecting the right to self-determination in favour of such ostensibly objective criteria, the CCP took the initiative away from the minority peoples. Instead, it arrogated to itself the power to decide who qualified for nationality status and what their rights would be.

This top-down approach is manifested in paternalistic attitudes to the minorities. Leading sociologist Fei Xiaotong, for instance, writes:

The national minorities generally are inferior to the Han in the level of culture and technology indispensable for the development of modern industry… Our principle is for the better developed groups to help the underdeveloped ones by furnishing economic and cultural aids.27

The similarity with the “white man’s burden”, the supposed civilising task of the European empires, led one writer to dub this idea the “Han man’s burden”. The same author shows how such elitism also “denied the minorities any political agency of their own”.28

Once officially endorsed, minorities were granted autonomy at provincial level, as with Xinjiang and Tibet, or, moving down the hierarchy, at prefectural, county or township level. In theory this gives them the right to develop their own policies but only under approval of the higher level authority.29 Although supposedly run by their eponymous minority, in reality, with a single exception, “all party secretaries in all five provincial-level autonomous regions have been Han”.30 Only the less powerful chairmen of the regional governments belonged to the relevant ethnic group.

The actual implementation of nationalities policy followed the political swings of China as a whole. Hence, during the Cultural Revolution period, many of Tibet’s monasteries and Xinjiang’s mosques were closed or destroyed as part of a campaign to eliminate the “four olds”.31 However, in reaction to the excesses of the preceding period, the 1980s were relatively liberal. Many places of worship were reopened and religious practice was accepted once again. Xinjiang’s Muslims, for instance, were allowed to travel to Saudi Arabia for the hajj pilgrimage for the first time in 15 years.32

However, from around the turn of the millennium there has been a distinct hardening of official attitudes. Already in 2000, Becquelin detected a “radical alteration of nationalities policies”.33 This was made explicit in 2011 when two academics close to the government coined the term “second generation ethnic policy”. This policy advocates the abandonment of any positive discrimination measures that assist minority people in favour of a more assimilationist “proactive forging of a common culture, consciousness and identity”.34

The second generation policy has not been formally adopted. However, under the leadership of President Xi Jinping there has been an assault on minority “privileges” such as one child policy exemptions and lower university entrance requirements. The right of people to be taught in their mother tongue has also come under attack as Chinese language instruction has been imposed, and concerted efforts have been made to curtail religious practice.35 Both of these measures contravene the constitution of the People’s Republic.36 Political scientist Christian Sorace describes the new policies as “undoing Lenin’’. Indeed, they are certainly a further step away from the Bolsheviks, but in truth the CCP left Lenin behind more than 80 years ago.37

Xinjiang

When the Communists came to power in 1949, they inherited the vast territories accumulated by the last imperial dynasty, the Qing, which ruled between 1644 and 1912. The region that became known as Xinjiang was carved out in the mid-18th century following a long and ultimately genocidal campaign against the Western, or “Zunghar”, Mongols.38 It was acquired for strategic reasons—to prevent another great nomadic confederation emerging—rather than for economic ones.

The conquest of Xinjiang, meaning “New Frontier”, was part of a longer-term process by which the once open steppe of Central Asia was partitioned by the expanding Russian and Chinese empires, with significant involvement from British India.39 The frontier stopped “where the Tsarist conquests stopped”, dividing “similar peoples instead of separating different peoples from one another”.40

Xinjiang covers a huge area—more than six times the size of Britain—so although it has less than 2 percent of the population, it makes up around a sixth of China’s land mass. The region is divided in two by the Tian Shan mountains. To the north is the former steppe land of the Zunghars, which in Qing times shared a frontier with Russian Central Asia, but now borders Kazakhstan.

Following its bloody conquest, the Qing repopulated this northern region by forcibly relocating Muslims from the Kashgar area. These people became known as “Taranchi”, meaning farmer. However, in the 20th century, they were subsumed under the rediscovered “Uyghur” ethnic category. This created the basis for Uyghur nationalists to lay claim to “Xinjiang in its entirety” rather than just the southern Uyghur heartland.41

The extremely arid Taklamakan desert lies at the heart of the larger southern part of Xinjiang. Most of the population lives in the oasis towns at the feet of the Tian Shan to the north and the Kunlun mountain range to the south. The “typical oasis”, orientalist Owen Lattimore wrote in the 1920s, “is placed near the end of a river flowing from the mountains into the desert, at a point where the flow of water retains enough impetus to be carried out fanwise in irrigation ditches.” Trade was “vertical” and “self-contained” between the mountain pastoralists who “bring down wool, hides and metals” to exchange with the oasis farmers for grain, cloth and simple manufactured products. There was little incentive for commerce between similar oases, and lateral trade was mostly long distance; both the northern and southern oasis towns lay along the routes that became known as the Silk Road.42

Two maps in Lattimore’s book Pivot of Asia neatly illustrate the congruence between the way people made a living and their ethnic group. In the northern steppe Kazakhs and Mongols practised pastoral nomadism. The Uyghurs were (and many still are) oasis agriculturalists, and the upland areas of the south were home to Kirghiz “alpine nomads”.43

According to government figures, by 2018, Uyghurs made up just over 50 percent of the 22.8 million population of Xinjiang, with Han comprising 34 percent. There were also 1.5 million Kazakhs and just over a million Hui—Chinese Muslims who are spread across China but concentrated in the northwest. Smaller numbers of other groups, such as Mongols and Kirghiz, make up the remainder.44

East Turkestan or an inseparable part of China?

Different versions of Xinjiang’s history are used by both Chinese and Uyghur nationalists to lay claim to this land. Communist Party dogma asserts that “Xinjiang has since ancient times been an inseparable part of China”.45 This is based on the efforts of the Han Dynasty, which ruled China between 206 BCE and 220 CE, to establish military colonies in the area in the last decades of the first millenium BCE as part of its long conflict with the nomadic Xiongnu people. However, as historian James Millward points out, full Han control of the Turfan and Tarim basin oases lasted only 125 years and they “never had a foothold in Zungharia”.46

The Tang dynasty, which ruled between 618 and 907, then enjoyed “some hundred years of relatively firm sovereignty over the Tarim city states” and “about twenty” years over Zungharia. However, they relied on an alliance with the East Turks to make their conquests and their rule was “indirect, with local elites left in place”. There were very few Chinese settlers.47

Almost a millenium passed before another dynasty, the Qing, established permanent Chinese control. This was a by-product of the Zunghar wars and was certainly not seen at the time as reconquering an integral part of the nation. “During the military campaign”, Gardner Bovingdon argues, “there was not a word about ‘unification’ or ‘reunification’.” Neither was it considered an “inseparable” part of the empire after the event; “on numerous occasions both the imperial house and much of the Qing policy elite seriously contemplated abandoning the colony”.48

In contrast to the contemporary situation, at least until the late 19th century, the Qing ruled with a “light hand”.49 Authority was delegated to the traditional local elites of the various peoples, supervised by Qing officials, and the state did not “interfere much in the Islamic legal system or religious matters”.50

Therefore, far from being an integral part of the empire, parts of what is now Xinjiang were only intermittently ruled by a Chinese state. When they did take over, it was to deny the oases’ resources to any hostile nomadic confederation rather than to integrate it into the empire.51 It was only after defeating a major rebellion, which had expelled Qing forces from the region for 13 years, that Xinjiang was incorporated as an imperial province in 1884.52 As late as the 1960s, when there was a real fear of invasion following China’s split with their erstwhile Russian allies, “planners viewed Xinjiang primarily as ‘strategic depth’ to slow a soviet assault and stretch out its supply lines rather than as a piece of the motherland to be held at all costs”.53

Unsurprisingly, Uyghur nationalists also draw on history to develop their own nationalist vision. However, although China’s historical claim to Xinjiang is flimsy, Uyghur assertions of “a history of more than 4,000 years”, in what they prefer to call “East Turkestan”, are highly problematic too.54 The mobility of the steppe nomads and the presence of the Silk Road trade routes made the region a melting pot of peoples and beliefs rather than the preserve of a single “nationality”.

The centre of the Uyghur empire, which lasted from 744 to 840, lay not in East Turkestan but in what is now Mongolia and helped keep the Chinese Tang dynasty in power.55 When the empire fell, some of these Uyghurs migrated to the oases of what is now Xinjiang, integrating with the existing population. They retained their language but, over the following centuries, their culture changed in almost every other respect. These former nomads settled as farmers, and they adopted the religions of the Silk Road—Manichaeism and Buddhism—and then later Islam.56

These small oasis settlements dotted along continental trade routes were absorbed by a variety of kingdoms and empires, none of which aligned with modern borders. When conversion to Islam was finally completed by the 16th century, the name “Uyghur” dropped out of use.57 Identities were both grander (Turkic or Muslim, befitting the vast sweep of Central Asia) and more local (Kashgarlik, Turpanlik and so on, reflecting the parochialism of oasis life).

The World Uyghur Congress claims the “Uyghurs and other peoples of East Turkestan valiantly opposed” foreign rule, revolting 42 times “with the purpose of regaining their independence”.58 Yet it is completely anachronistic to see these events as nationalist uprisings. Xinjiang was an entity carved out by the Qing that had never had an independence to regain. Revolt was prompted, as the Qing dynasty entered its terminal crisis in the mid-19th century, by “economic distress” and the “rampant misrule” of both Qing officials and the local elite they relied on.59

The biggest uprising was started in 1864 by Hui Chinese Muslims (then known as Dungan) before spreading to Turkic Muslims, none of whom would have identified as Uyghur at this time. Various aristocratic factions attempted to lead the movement, but Yakub Beg eventually took over at the head of an army from neighbouring Kokand. Conquering most of Xinjiang, Yakub Beg at times allied with Han Chinese and at others fought Uyghurs. However, he alienated the population to such an extent that the ailing Qing could retake Xinjiang with little resistance in 1877. Yakub Beg, Millward concludes, “was no Uyghur freedom fighter”.60

The development of Uyghur nationalism bears comparison to that of early Chinese nationalism, which emerged among disgruntled intellectuals at the end of the 19th century in response to the depredations of the European powers. Sun Yatsen, the statesman and political philosopher often seen as the father of the nation, could still complain that in 1924, “The Chinese people have shown the greatest loyalty to family and clan with the result that in China there have been family-ism and clan-ism but no real nationalism”.61 It was only the experience of the brutal Japanese occupation during the Second World War, and the resistance to it, that spread nationalist thinking to the mass of the people.

Similarly, the term “Uyghur” began to be revived by exiled Taranchi and Kashgari intellectuals under Russian influence in the early 20th century.62 In the 1920s, according to one contemporary account, identification as “Uyghur” was still “not widespread”.63 The experience of life under brutal Chinese warlord regimes in the Republican period between 1912 and 1949 strengthened nationalist sentiment sufficiently to ensure Uyghur inclusion in the Communists’ ethnic classifications after 1949.64 Yet the goal of “fostering national identification among the province’s Turkic-speaking Muslims” was “still far from realised at the inauguration of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region” in 1955.65

Based on research in the 1980s, Justin Rudelson argues that, due to the fragmentation inherent in oasis society, nationalist sentiment remained weak among the Uyghurs. Intellectuals tended to be “secular, virulently anti-Islamic, pan-Turkic nationalists”, whereas peasant farmers were “devout Muslims” with strong local identities, and merchants trading outside the region identified more with China. However, the greater mobility occasioned by rapid economic development and the experience of Chinese repression have since strengthened Uyghur identity.66

Mass Uyghur nationalism has been forged, as Chinese nationalism was, in the furnace of foreign oppression. However, there is a conflict at the heart of Uyghur nationalism between the promotion of Uyghur ethnicity and its claims to East Turkestan, which is very much a multi-ethnic area. The Chinese state can play on fears among the other minority groups that Uyghur rule would reproduce ethnic oppression on a more local scale.

Development and exploitation

Until the late 19th century, there was little attempt to exploit Xinjaing’s natural resources along the lines of the contemporary European colonies.67 Nevertheless, after being elevated to provincial status in 1884, the borders of Xinjiang were more clearly delimited, marking its transformation from a traditional tributary zone to a fully fledged colony.68

In the early 20th century, China lacked both the capital and expertise to develop the region effectively and so turned to Russia for investment. Enormous distances and a severely underdeveloped infrastructure—the railway line to the capital city, Urumqi, was only completed in 1962—meant that transport to cities in China proper would be prohibitively expensive. Because of this, assets such as the oil wells at Dushanzi and various mining operations were all situated in the northernmost parts, where their output could be exported across the border to Russian Turkestan.69 This was to have long term consequences for patterns of economic development and ethnic demography in Xinjiang. To this day, industry is concentrated in the north, where Han Chinese make up the majority of the population, but most Uyghurs live in the less developed (and so poorer) south.

If the Communists initially took over Xinjiang primarily for security reasons—China and the Soviet Union were already uneasy allies—there were important economic considerations too. The oil and non-ferrous metal extraction operations pioneered by Russians were soon in Chinese hands. A programme of infrastructure development was initiated to orient trade eastward towards China proper, rather than over the border to Russia.70

Another product of the security-economy nexus was the creation of the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corp (XPCC), also known as the “bingtuan”. Based on a long tradition of settling soldiers in border regions as farmers, the bingtuan was created to consolidate Communist control of this frontier region. It remains under the direct control of Beijing rather than the provincial government. In subsequent years, this quasi-military organisation grew to gargantuan proportions. It had 3.1 million members by 2018, almost 14 percent of the provincial population.71 About 86 percent of these were Han Chinese, reflecting the organisation’s history of absorbing the majority of Han immigrants.72

Despite this, development in Xinjiang remained slow until the 1990s. Then, through campaigns such as “Open up the West” and later the Belt and Road Initiative, the central government began concerted efforts to spread China’s economic boom westwards from the eastern coastal cities.

This was also a process of “assimilation and national territorial integration”.73 Economic growth and repression are seen by the Communist leadership as mutually reinforcing. In the words of President Xi: “Development is the foundation of security, and security is the precondition for development”.74 Although this approach worked to some extent in much of China, recent growth in Xinjiang has only served to exacerbate existing divisions, and the level of repression has reached a level that inhibits the economy.

In practice, development in Xinjiang turned out to mean ramping up output of primary products, which already dominated the economy, for use as raw materials in factories in China proper. Under the slogan “One White and One Black”, cotton production and oil extraction dramatically increased.75

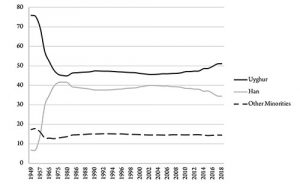

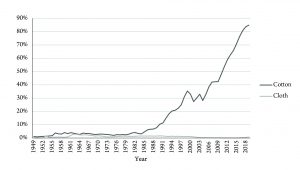

Figure 1 shows how Xinjiang’s contribution to national cotton output leapt from just a few percent in the 1980s to no less than 85 percent by 2019. It also indicates how marginal Xinjiang was to the national economy before the 1990s. Over the same period, cloth production declined proportionally, highlighting the province’s continuing role as a source of primary products rather than as a manufacturing centre. In 2018, 37 percent of the province’s cotton was produced by the overwhelmingly Han XPCC.76 The XPCC’s control of water sources and economies of scale give it a distinct advantage in agriculture over the small scale farming prevalent in the Uyghur south.77

Figure 1: Xinjiang cotton and cloth production as percentage of national totals

Source: China Data Online.

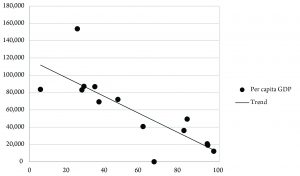

Xinjiang’s growing importance as a site of energy production is shown in figure 2. The region already accounted for 5 percent of national oil output in 1990, but production has almost quadrupled since then. In the same period coal and electricity output multiplied by over 10 and 50 fold respectively. Xinjiang also accounts for nearly 30 percent of national natural gas production.78

Source: China Data Online. Gaps reflect the incomplete data for coal.

China has been a net importer of oil since 1993.79 However, imports from the Middle East come by tanker through the strategically vulnerable Strait of Malacca, a narrow shipping lane between Malaysia and Indonesia. So, to diversify supply, since the early 2000s oil has been imported from neighbouring Kazakhstan via a pipeline that runs through Xinjiang, making the province a key component in China’s energy security.

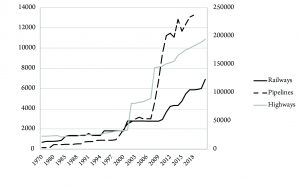

All this required a massive investment in infrastructure. Figure 3 shows a sudden increase from around the millennium following decades of much slower development. This infrastructural development is about control as well as commerce. US researcher Jonathan Hillman draws a comparison between China’s Belt and Road Initiative, in which Xinjiang is a key link, and the expansion of European powers in the 19th century. These states used infrastructure projects to “expand their influence at the expense of indigenous people, the environment and economic stability”.80 The extension of the rail network to Kashgar and beyond has drawn isolated Uyghur communities closer to China.81

Figure 3: Railways, pipelines (left axis) and highways (right axis) in kilometers

Source: China Data Online.

Immigration and inequality

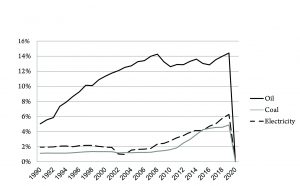

Economic growth and improved living standards were supposed to “promote the unification of all peoples towards the Communist Party”, as one official hoped, but the Uyghurs have become progressively more alienated from the CCP.82 One cause of resentment is the influx of Han Chinese to the region. In 1949, Han made up just 7 percent of the population, and Uyghurs accounted for 76 percent. However, as a consequence of government resettlement policies, by 1978, they were almost equal, with Han at 42 percent compared to 46 percent for Uyghurs.

It is a common assumption that the recent push to develop Xinjiang has been accompanied by mass Han immigration, but the figures do not bear this out. Though the Han population continued to increase in absolute terms until recently, it has been declining proportionally since 2003 and absolutely since 2015, as can be seen in figure 4.83

Figure 4: Percentage of ethnic groups in Xinjiang population