Environmentalism is a crucial societal reaction to capitalism’s ecocide.1 In all its political guises, it can be interpreted as an expression of revulsion at the wanton destruction and barbarism that capitalist society has unleashed upon nature. However, although its advocates share a core philosophy—that the living Earth is unique and finite and should be treated with care for the sake of nature and human civilisation—environmentalism itself is a very broad political church. To the extent that environmentalism can be described as a social movement, its political unity coalesces around the symptoms of capitalism’s ecological dysfunctionality. This focus on symptoms encourages a degree of political consensus on the significant environmental “issues” that have emerged such as climate change, biodiversity loss and pollution.

However, once deeper causal factors and remedial steps are considered, environmentalism breaks down along the well-established lines of “mainstream” (pro-capitalist) and “critical” (anti-capitalist) social theories. Mainstream approaches advocate capitalist and technocratic solutions, such as nature financialisation and carbon trading, that are consistent with the profit motive and corporate power. Critical approaches reject capitalist norms in favour of alternative and redistributive value systems or democratic controls over corporate and ruling class actors.

This political division of environmentalism into right and left is important. Marxist, socialist and ecosocialist strategies within environmental politics need to highlight these underlying political divisions. By doing so, we can make meaningful and effective environmental gains that contribute to societal transition and are enduring in the face of mainstream co-option. On many fronts, such radical interventions are straightforward. Billionaires such as Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk, who claim to hold the keys to climate change mitigation through “philanthropy”, are touting limited “solutions” consistent with their own astronomical wealth.2 Nevertheless, there is one topic that runs across environmentalism’s political spectrum and poses a significant challenge for socialist intervention because it obfuscates environmental politics: human population growth and “overpopulation”.

Ideologically, especially during the Cold War, the overpopulation argument has played an important function as a victim-blaming narrative—painting the “underdeveloped” countries in the Global South as victims of their own demographic folly. It usefully ignores capitalism and its histories of imperialism, colonialism and neoliberalism. Yet, concerns over rapid population growth and the notion of overpopulation have played a more nuanced role within modern environmentalism since it first developed in the early 1960s. Environmentally, the argument that rapid population growth is incompatible with our finite planet appears intuitive. Indeed, influential natural historians and environmentalists such as David Attenborough have focused much of their attention on advocating population control as they have witnessed ecological destruction and biodiversity loss.3

Some population concerns within environmentalism reflect straightforward disciplinary bias from the ecological and biological sciences. Simplified ecological arguments claim that we are a rogue species that has surpassed the “natural limits” of Earth and overshot our “carrying capacity”. They assume there is an optimum (inevitably lower) population size for humanity, which, if realised, would return us to a balanced relationship with nature. This erroneous perspective leads some to raise concerns about population growth from misanthropic and anti-human positions; it can even encourage contorted eugenic and Malthusian arguments that see wars, famines and diseases as nature’s way of controlling our numbers. Ecological generalisations, eugenics and misanthropy are easy to rebuke from a socialist perspective—they are crude reactionary positions that often claim to show large-scale demographic statistical associations without sufficient analysis or interpretive care. In this way, broad correlations between population numbers and environmental crises are presented as causal rather than co-symptomatic of capitalism’s assault on nature.

As we shall discuss below, socialism has a rich heritage of refuting crude ideological arguments around overpopulation—especially where Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels countered the work of Thomas Malthus and his associates. Malthus’s 18th century concerns that population growth would outstrip food production were more or less immediately undone by early agricultural expansion and improvements after the Industrial Revolution. The more recent application of population growth concerns to environmentalism can be construed as just a modern reiteration of these ideas; reactionary authors have sought new ground on which to make their views on overpopulation relevant.

The degree to which such authors contort their arguments to maintain a focus on population numbers instead of capitalism’s systemic failures is remarkable. As birth rates and projections of population growth have fallen, infamous writers such as Paul Ehrlich—who we will discuss in depth shortly—have adapted their arguments. They argue that population growth should still be the focus of environmental attention, but that the number of “super consumers” is now the problem.4 Recently, other mainstream approaches have attempted to integrate population growth concerns with economic arguments for nature financialisation as the means by which nature can be protected from rich and poor alike.5

However, despite the blatant ideological functions of population growth and overpopulation concerns, there is been a resurgence of these arguments within activist groups such as Extinction Rebellion and on the left. In his recent book on environmental protests in Britain, Extinction Rebellion activist and transport expert Steve Melia comments that, almost four decades since the Club of Rome concluded there were “limits to growth”, “economic and population growth have continued unabated”.6 Melia’s passing reference to unabated population growth might be considered minor, but others in the environmental movement and on the left have made these argument more explicit. In 2013, naturalist David Attenborough said, “All of our environmental problems become easier to solve with fewer people, and harder—and ultimately impossible—to solve with ever more people”.7

Even the revolutionary left is not immune from these arguments. For example, the British socialist Alan Thornett has written:

Africa faces the most dangerous situation. Nigeria, for example, Africa’s most populous and most ethnically diverse nation…is now expected to reach 278 million by 2050, and to surpass that of the United States by 2060—at which point it would become the third most populous country in the world.8

Later he continues:

I am not arguing that rising population is the root cause of the ecological crisis… That is the fault of the capitalist system of production and the commodification of the planet… What I am arguing is that rising population is a major contributory factor.9

Such simplistic population growth arguments continue to be brought into play within the sphere of progressive environmental politics. This article is written, in part, to counter these. It also highlights the dangers that population arguments bring when used by racists, the far right and capitalist interests.

Marx and Engels’s critique of Malthus

The figure most associated with overpopulation theory is Thomas Robert Malthus.10 Malthus was born into a family of small landholders. He studied mathematics at Cambridge, becoming a curate in the Surrey village ofWotton in 1789. While a clergyman, he became interested in political economy and read extensively. He is best known for An Essay on the Principle of Population, first published in 1798 and revised through six editions, the final being published in 1826. The Essay was tremendously influential—the two most important figures of early evolutionary theory, Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace, both saw it as a key work. Malthus went on to become Chair of Political Economy at the East India Company College. His pupils included Charles Trevelyan, later in charge of the British government’s response to the Irish Great Hunger, and many other colonial administrators. Many years after Malthus’s death, his ideas still shaped state policy. As Mike Davis notes, “Malthusian principles, updated by Social Darwinism, were regularly invoked to legitimise Indian famine policy at home in England”.11

Today, Malthus’s Essay is mostly remembered for its argument that population increases at a geometric rate (1, 2, 4, 8, 16 and so on) which would inevitably outstrip food production, which only increased in arithmetic progression (1, 2, 3, 4 and so on). However, Malthus’s Essay should chiefly be understood as a response to radical ideas in the aftermath of the French Revolution.12 Chapter 1 of the first (1798) edition of the Essay concludes that the “natural inequality of the two powers of population and of production in the earth” meant no “escape from the weight of this law, which pervades all animated nature”:

No fancied equality, no agrarian regulations in their utmost extent, could remove the pressure of it even for a single century. And it appears, therefore, to be divisive against the possible existence of a society, all the members of which should live in ease, happiness and comparative leisure; and feel no anxiety about providing the means of subsistence for themselves and families.13

Later in the same edition he writes:

Man cannot live in the midst of plenty. All cannot share alike the bounties of nature. Were there no established administration of property, every man would be obliged to guard with force his little store. Selfishness would be triumphant.14

Malthus’s attacks on radical ideas were also an attack on the lives of the poor. After deciding that population growth meant economic equality was not possible, he concluded that charity was inadvisable. As Malthus wrote:

With regard to illegitimate children…they should not be allowed to have any claim to parish assistance, but be left entirely to the support of private charity. If the parents desert their child, they ought to be made answerable for the crime. The infant is, comparatively speaking, of little value to the society, as others will immediately supply its place.15

Helping the poor, Malthus claimed, would only cause more population growth:

We cannot, in the nature of things, assist the poor, in any way, without enabling them to rear up to manhood a greater number of their children.16

The publication of the first edition of the Essay saw an immediate critical response. William Godwin, whose radical work had been inspired by the French Revolution, was one of the key targets of Malthus’s Essay. He wrote: “Advocates of old establishments and old abuses…could not have found a doctrine more to their hearts’ content and more effectual to shut out all reform and improvement for ever”.17 Godwin initially agreed with Malthus’s main argument, but believed—in fitting with his own ideas—that the “problem” of population growth could be dealt with through personal decisions about children.18 Later, his position hardened. In November 1820, Godwin published his book, Of Population, arguing, against Malthus, that “inequality was the direct result of the political and moral errors that Malthus’s theory apparently sought to absolve”. Godwin’s book used census data from around the world to attack Malthusianism.19 However, it was Marx and Engels who firmly located a critique of Malthus within the wider context of society and historical change. Nearly 50 years after the initial publication of Malthus’s Essay, Engels’s The Condition of the Working Class in England argued that Malthus’s ideas had become the “pet theory of all genuine English bourgeois”.20

Like Godwin before him, Engels noted that Malthus’s theory justified the inequality of capitalist society. He highlighted how Malthus always linked his theories of overpopulation to wider economic debates:

We may sum up its final result in these few words: that our Earth is perennially overpopulated, whence poverty, misery, distress and immorality must prevail; that it is the lot and the eternal destiny of mankind to exist in too great numbers, and therefore in diverse classes, of which some are rich, educated and moral, and others are more or less poor, distressed, ignorant and immoral…that charities and poor-rates are, properly speaking, nonsense, since they serve only to maintain, and stimulate the increase of, the surplus population, whose competition crushes down wages for the employed; that the employment of the poor by the Poor Law guardians is equally unreasonable, since only a fixed quantity of the products of labour can be consumed, and, for every unemployed labourer thus furnished employment, another hitherto employed must be driven into enforced idleness, whence private undertakings suffer at cost of Poor Law industry. In other words, the problem is not how to support the surplus population, but how to restrain it as far as possible.

Thus, Malthus “declares in plain English that the right to live…is nonsense”.21

Marx and Engels were the most trenchant critics of Malthus’s economic and population theories. Space prevents a detailed critique of Malthus’s economic work.22 Nonetheless, we will draw attention to the way that Malthus’s ideas on population fitted with his economic theory. He argued, for instance, that because underconsumption was the main driver of economic crisis, solving this meant expanding the class of “unproductive consumers” to increase those able to purchase commodities. In a letter to the political economist David Ricardo in 1821, Malthus wrote, “A certain proportion of unproductive consumption…is absolutely and independently necessary to call forth the resources of a country”.23 For Malthus, “unproductive consumers” were non-producers such as landowners, but also state employees who “ensure the consumption that is necessary to give the proper stimulus to production”.24 Marx pointed out that Malthus’s argument served both to “demonstrate that the poverty of the working classes is necessary” and to “demonstrate to the capitalists that a well-fed tribe of church and state servants is indispensable for the creation of an adequate demand for their commodities”.25

Marx did acknowledge Malthus as superior to other bourgeois historians, not least because he “amplifies” the antagonisms between classes and “blazons them forth”.26 Yet, this did nothing to restrain his anger at Malthus’s ideas. In his Grundrisse, Marx calls Malthus a “baboon”:

Malthus implies that the increase of humanity is a purely natural process, which requires external restraints and checks to prevent it from proceeding in geometrical progression. This geometrical reproduction is the natural reproduction process of humanity. He would find in history that population proceeds in very different relations. Overpopulation is likewise a historically determined relation. It is in no way determined by abstract number or by the absolute limit of the productivity of the necessaries of life, but by limits posited rather by specific conditions of production.27

Marx and Engels attacked Malthus from several directions. This included highlighting the lack of scientific evidence for Malthus’s central argument—that population grows in geometric progression, but resources only grow in arithmetic progression. Marx was scathing, saying that this argument, which is so central to Malthus’s thinking, was “fished purely out of thin air”.28 He also noted that Darwin’s Origin of the Species undermined Malthus on this point; Darwin argued that geometrical population growth applied to plants and animals as well as humans, whereas Malthus insisted such growth was only applicable to humans.29

Crucially, Marx argues that Malthus abstracted humans from our historical context. In a famous passage Marx notes that overpopulation meant different things at different points in human history: “How small do the numbers that meant overpopulation for the Athenians appear to us!” For Marx, the specific social relations pertaining in a given society imbue overpopulation with a particular meaning: “An overpopulation of free Athenians who become transformed into colonists is significantly different from an overpopulation of workers who become transformed into workhouse inmates.”

Marx continues by arguing that Malthus’s key mistake was to view the question of population in an ahistorical fasion, which, furthermore, imposed his theory on reality rather than learning from the actual historical evidence:

Real history appears to Malthus in such a way that the reproduction of his natural humanity is not an abstraction from the historic process of real reproduction, but just the contrary, that real reproduction is an application of the Malthusian theory. Hence the inherent conditions of population, as well as of overpopulation, at every stage of history appear to him as a series of external checks that have prevented the population from developing in the Malthusian form.

He continues:

Malthus transforms the immanent, historically changing limits of the human reproduction process into outer barriers; and he transforms these outer barriers to natural reproduction into immanent limits of natural laws of reproduction.30

In opposition to this ahistorical argument, Marx and Engels argued that it was impossible to come up with a general law of population for humanity. Instead, they contended that any attempt to create premisses for understanding population growth must be rooted in historical context:

The working population produces both the accumulation of capital and the means by which it is itself made relatively superfluous; and it does this to an extent that is always increasing. This is a law of population peculiar to the capitalist mode of production; and in fact every particular historical mode of production has its own special laws of population, which are historically valid within that particular sphere. An abstract law of population exists only for plants and animals, and even then only in the absence of any historical intervention by man.31

Under capitalism, Marx and Engels argued, unemployment and underemployment were not the result of too many people. Instead, they were the consequence of the system of production, which produced only in the interests of profit. Since each person can produce more than they need, a growing population ought to be able to satisfy its own requirements—especially given the advances in productivity opened up by the application of modern science. As Engels explained in 1844 Outlines of a Critique of Political Economy:

Means of employment are not means of subsistence. The means of employment increase only as the final result of an increase of machine power and capital, whereas the means of subsistence increase as soon as there is any increase at all in productive power.32

Engels recognised that the work of scientists like Sir Humphry Davy and Justus von Liebig had dramatically improved agricultural yields. He argued that these types of technical improvements could allow far larger populations than had hitherto been possible. Additionally, there was a great deal of land that had been uncultivated or underproductive that could be used to produce food for growing populations. For Engels, it was “ridiculous to speak of overpopulation” while “the valley of the Mississippi alone contains enough waste land to accommodate the whole population of Europe” and “only one third of Earth can be described as cultivated.” Here, he is guilty of ignoring that lands such as the Mississippi Valley were already inhabited by Indigenous people. Nevertheless, Engels was correct to point out that developments in science and production would, even given the irrational nature of capitalist production, enable larger populations to be supported.

Subsequent developments, including the Green Revolution of the 1950s, have demonstrated capitalism’s ability to use new technology to increase available food far beyond so-called Malthusian limits.33 Of course, Engels and Marx never suggested that limitless population was possible; they merely pointed out the inaccuracies and lack of scientific evidence in Malthus’s core ideas.

So, why then were people hungry? Engels explains:

Too little is produced; that is the cause of the whole thing. But why is too little produced? Not because the limits of production—even today and with present-day means—are exhausted. No, it is because the limits of production are determined not by the number of hungry bellies but by the number of purses able to buy and to pay. Bourgeois society does not and cannot wish to produce any more. The moneyless bellies, the labour that cannot be utilised for profit and therefore cannot buy, is left to the death rate.34

For Marxists, hunger, as well as lack of access to resources, housing, education, employment and so on, was not and is not a function of population. Instead, it is related to the structure of society. Today, people live in inadequate housing, lack food and have inadequate access to essential services because they are unable to pay or due to the erosion of public services originally granted during periods of expanding capitalism.

Paul Burkett argues that Malthus’s arguments are important to the ruling class precisely because they offer such effective justification for their own system. For the capitalists, bent on maximisation of profit, Malthus “provided ideological justification for capital’s treatment of human beings and their natural conditions as superfluous and disposable whenever they cannot serve as vehicles for profit and accumulation”.35

So, how might the issue of population relate to a society where production has been transformed in order to provide for the needs of the whole population? Later in his life, Engels was engaged in debates about the question of population and communist society. In 1881, in a discussion with the German Marxist Karl Kautsky during a resurgent debate about overpopulation, Engels noted the “abstract possibility” that “limits will have to be set” on the number of people in society. However, he also cautions:

If at some stage communist society finds itself obliged to regulate the production of human beings, just as it has already come to regulate the production of things, it will be precisely this society, and this society alone, which can carry this out without difficulty. It does not seem to me that it would be at all difficult in such a society to achieve a result through planning that has already been produced spontaneously and without planning in France and Lower Austria. At any rate, it is for the people in the communist society themselves to decide whether, when and how this is to be done and what means they wish to employ for the purpose. I do not feel called upon to make proposals or give them advice about it. These people, in any case, will surely not be any less intelligent than we are.36

Engels noted that he had made a similar point in his 1844 Outlines of a Critique of Political Economy, which we quoted from earlier. There, Engels argued that, were Malthus right, it would only be a socialist society that could manage demographic change in ways that did not scapegoat the poorest and most vulnerable in society. The revolutionary overthrow of capitalism would transform the relationship between society and nature, giving the collective producers the ability to manage their relationship to nature in a rational way. As Burkett points out:

Compared to class-divided societies, including anarchically competitive capitalism, communism’s collective-democratic relations would more effectively “regulate” human production and reproduction in a environmentally sustainable fashion.37

Such arguments should not be seen as giving ground to Malthusianism. On the contrary, they highlight how a socialist society could solve problems of hunger and unemployment, ensuring ordinary people had the knowledge and democratic access needed to make important social decisions about matters such as demographics. Such an understanding is far from that offered by Malthus; it is much closer to Godwin’s ideal of a universally educated population able to engage in real political and democratic debate.

Today, Malthus’s ideas have been appropriated by some sections of the environmental movement. Yet, as John Bellamy Foster has pointed out, Malthus had nothing to say about wider ecological issues. In contrast to the neo-Malthusians, Malthus never generalised from his views on population and food to wider issues such as resource shortages. Indeed, he argued quite the opposite. As Foster emphasises, according to the first edition of his Essay, Malthus saw “raw materials” as being available “in as great a quantity as they are wanted”. Foster writes:

There can be little doubt that the real aim of the neo-Malthusians…is to resurrect what was after all the chief thrust of the Malthusian ideology from the outset: that all of the crucial problems of bourgeois society, and indeed of the world, could be traced to excessive procreation on the part of the poor, and attempts to aid the poor directly would…only make things worse.38

Population growth, demography and capitalism

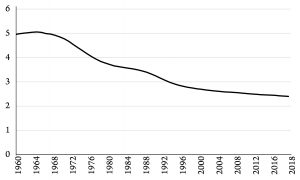

The resurgence of population growth concerns appears strange when set against the demographic patterns of the last 50 years and consequent population projections. If only the issue of high birth rates is considered (despite its merely partial role in population growth, discussed below), then the advocates of population control ought to be some of the most content environmentalists around. Despite the doom-laden tone of the population debates of the 1970s and 1980s, birth rates as measured by “total fertility rate” (TFR)—the average number of children born to the average woman over her reproductive lifespan—have fallen dramatically across the world over the last 40 years (figure 1). Indeed, globally, our collective TFR of around 2.5 is now at the “replacement level”; that is to say, the number of children being born has fallen to a rate only sufficient to replace their parents under prevailing life expectancies.

Figure 1: World fertility rate (births per woman), 1960-2018

Source: World Bank, 2021.

The United Nations’ projections for global population size now peak at around 11 billion by the end of this century.39 These predictions assume that mortality will continue to decline to the point where births and deaths across the world reach equivalence and replacement TFR is maintained. This would mean a rate of roughly 2.1 children per woman insofar as mortality rates equate to Western life expectancies. Birth rate declines have occurred across the world over the last 40 years. Indeed, for some countries, such as South Korea and China, the birth rates are so far below replacement level now that population declines and “ageing populations” are seen as growing problems, resulting in calls for pro-natalist policies to be introduced.40

With the global TFR now at replacement level, the motivations for a continuing environmental focus on population growth should be scrutinised. The fact that fertility levels are still highest in the Global South (particularly sub-Saharan Africa) means that continued prioritisation of population growth within part of the environmentalist movement cannot be seen as an apolitical scientific stance. Environmentalists who focus on population growth and birth control are thus—as discussed below—open to accusations of racism and cultural chauvinism.

As a historical phenomenon, the rapid increase in our numbers has been uniquely associated with capitalism. However, that association needs to be examined with care. Yes, global population has risen sharply since the Industrial Revolution—from around half a billion in 1750 to 7.7 billion today. Another 3 to 5 billion are expected to join us by the end of the 21st century.41 On the surface, as presented in the kind of crisp and selective graphs that punctuate the websites of various environmental NGOs, this growth appears to correlate with other outputs of industrial capitalism such as poverty, atmospheric carbon dioxide, deforestation and species extinctions. Yet, correlation is not the same as causation. The human population growth that has advanced alongside these trends is just one more symptom of capitalism’s chaotic class dynamic.

The interplay between capitalism and population growth is very often misunderstood. Population myths reflect Western cultural bias and bourgeois judgements that reproductive behaviour in humans is a shared species attribute, rather than a sophisticated combination of cultural, gender, class and material considerations. Some straightforward demographic errors are ideologically driven misinterpretations. For example, a simple arithmetical and abstract focus on “high birth rates” ignores the fact that population growth is initially driven by declining mortality as a result of improvements in public sanitation, disease control and healthcare provision. With the rare exceptions of post-war baby booms, the issue of high birth rates comes into play not because households are having more children, but because declining mortality sees more offspring survive to adulthood. It is the lag between declines in mortality and falling birth rates—themselves resulting from the cultural and material impacts of economic development—that causes population growth.

From a socialist perspective, the health improvements and declining mortality that drive population growth are obviously positive signs of social progress—the more so because they have often been achieved through class struggle. However, there are some misanthropic “deep green” arguments that compare our numerical rise to a planetary plague or virus whose growth must be kept in check through wars, famine, disease and environmental collapse. Most liberals worried about population growth are at least decent enough to focus their efforts on reducing birth rates rather than increasing mass mortality. Despite these stated good intentions, however, their advocacy of population reduction through birth control measures is problematic. Of course, socialists are, rightly, in favour of free and universal access to birth control for women. Nonetheless, an exclusive political focus on fertility control policies and programmes is a glaring example of capitalism’s victim-blaming ideological techniques. It is also a position that finds fertile ground in racism.

To understand the overlap between the politics of population control, capitalism and racism, we need to look at how demographic arguments have developed. The many myths and misconceptions that surround population growth have emerged due to the political use and abuse of demography to justify the capitalist status quo. Defenders of capitalism have used population growth as polemic to counter the threats to capitalism posed by radical reforms and revolutionary change. Historically, the focus of their ire has always been higher birth rates amongst other rival classes—proletarian and peasant—and the poor.

In the 19th century, the notion that poverty was a self-inflicted condition resulting from too many children informed the moral atmosphere in Victorian Britain, Europe and the US. As Western birth rates declined during the 20th century, neo-Malthusians turned their attention towards the Global South and the rapid population growth that emerged as new nation states threw off the colonial yoke. Western concern over population growth shifted from domestic poverty and cultural prejudices against beliefs such as Catholicism, towards issues of “economic development” and post-colonial struggles for self-determination. In the last 50 years, environmental degradation has merely been added to this blame game, with the defenders of post-war capitalism continuing to focus their population concerns on the Global South.

Between the late 1960s and the mid-1990s, UN and international “aid” agencies such as the World Bank sponsored various attempts to develop explicit population control measures through birth control targets, policies and programmes across the Global South.42 These efforts were informed by a misreading of the demographic experience of China, where birth rates were already near replacement level before the infamous One Child Policy was introduced in 1980.43 Another driver was the moral panic that followed India’s 1971 census, which revealed rapid population growth. In this atmosphere, enforced sterilisation programmes were even introduced under Indira Gandhi, India’s prime minister during the state of emergency in the mid-1970s that saw clampdowns on her political opponents. The mistaken belief that anti-natal policies could be enforced through state-sponsored family planning programmes was encouraged by right-wing and neo-Malthusian thinkers such as Stanford University professor Paul Ehrlich. In a modern parallel to Malthus, Ehrlich published The Population Bomb at the height of the global struggles of 1968, painting the poor of the Global South as an existential threat to human civilisation. These reactionary positions were countered by the slogan “Development is the best contraceptive” by activists and radical governments in the Global South at the World Population Conference in Bucharest in 1974. In the atmosphere of confidence following decolonisation and the defeat of the US in Vietnam, these states pointed out that the West had been able to complete the “demographic transition”—from high birth and death rates to low birth and death rates—through economic development alone.

Since the 1990s, as fertility rates have declined across the world, the advocates of population control have been forced to temper their arguments. The poor masses of the Global South are still their primary targets. However, in addition to advocating population control, the latest generation of neo-Malthusians have focused on women’s education and employment in regions where birth rates are still relatively high such as sub-Saharan Africa. Here, the assumption is that education-based gender empowerment can encourage women in the Global South to have fewer children as their material empowerment challenges patriarchal cultural practices.44 Of course, targeted efforts to empower women living in rural poverty are to be applauded and there is little doubt that there is a statistical association between levels of women’s educational attainment and lower birth rates. Yet, there is a great deal of uncertainty over the causal and motivational mechanisms at play beneath that correlation. Women’s educational attainment itself is a product of economic development and class-based access to education; the association between female education and decisions over childbirth is co-symptomatic of deeper socio-economic trends including reduced poverty and higher household levels of material security. Indeed, the general correlations between economic indicators and fertility rates are almost identical to those for female education. This suggests that material factors such as poverty, health, employment and security in old age are overridingly influential in shaping family size irrespective of cultural norms and practices.45

In the end, the various camps—radical and reactionary—that participated in the post-war population debates have all been caught out by the rapid decline in birth rates that have occurred in the early decades of the 21st century. Whatever the causes of that decline, however, neoliberalism is obviously not a humane and progressive social context for demographic transition. Its chaotic economic strategies may have driven declines in fertility through regressive economic restructuring and through the cultural influences as individualism and consumerism have penetrated the Global South. Yet, these outputs of neoliberalism cannot be judged as demographic victories when set against the ideology’s high costs in environmental degradation, extreme inequalities and wasted human potentials. Human population growth may be slowing, but our global society’s long-term viability is far from secure. The decrease in fertility rates and looming population decline may seem like a success to those who preach the “overpopulation” argument; nevertheless, they will reveal themselves as hollow victories when they fail to lead to the expected environmental and social improvements.

Demographically, apart from sub-Saharan Africa and sections of the Middle East, most countries, and the globe itself, have seen fertility rates approach or fall below replacement levels. This means that nearly all the world’s remaining population growth projected is a product of “population momentum”—the demographic echo of previously high birth rates as young people move into reproductive age, even if they have fewer children themselves. This phenomenon plays out just as effectively in reverse with low fertility; concerns are now being expressed over future population declines and ageing population structures in “advanced” countries.

The fact that overpopulation arguments continue even though global population growth is essentially plateauing, tells us a great deal about their proponents’ desperation to deflect blame away from capitalism. In the hope of pulling well-meaning activists away from such neo-Malthusians, we must be prepared to argue that recent reductions in birth rates are a hollow victory. Instead of adopting a humane approach with poverty alleviation at its core, population control advocates continue to promote fallacious arguments—as they did even as the Global South was being thrown to the economic wolves by the international architects of neoliberalism.46 Whatever the causes of recent rapid birth rate declines, we know they are a far cry from the social and health measures that would accompany a just demographic transition under socialism.

Contemporary racism and population debates

Discussing global population size need not be racist. However, because most contemporary population growth is in Africa and Asia, arguments that seek to link population size to resource use, hunger and environmental destruction inevitably become tinged with racism. Clear socialist arguments that contextualise the issue within capitalism are important to counter this.

The modern debate about population has been closely associated with the politics of immigration and migration. Although discussing the politics of population is not inherently racist, it is notable that the issue is often taken up by the right and far right, who use it to strengthen a racist narrative. Thus, the overpopulation narrative is often linked solely, or at least mostly, to concerns about the Global South. Moreover, the right use arguments that link migration and population levels to wider political questions. These arguments are often closely linked to the misuse of per capita consumption figures, which we discuss later in this article.

In some parts of the world the environmental movement has had close links to anti-immigrant ideas. Recent descriptions of “eco-fascist” politics often portray this as a new phenomena, but these far right and fascist ideas have deep roots.47 In his 1971 radical ecological book, The Closing Circle: Nature, Man and Technology, Barry Commoner highlights a US newspaper advert by the Campaign to Check the Population Explosion, which argued:

A hungry, over-crowded world will be a world of fear, chaos, poverty, riots, crime and war. No country will be safe, not even our own… What can we do about it? A crash program is needed to control population growth both at home and abroad.48

Similar sentiments were expressed in a 2008 advert placed in the New York Times by an organisation calling itself “America’s Leadership Team for Long Range Population-Immigration-Resource Planning”. The ad began by saying that the US’s population was racing from 300 million towards a projected 400 million and asked what this meant for the environment. Noting environmental problems such as air quality, water consumption and traffic, it argued:

All these problems are caused by a large and rapidly growing population. The more people there are, the more challenging the problems become… Population growth is destined to be exponential. But the reality is that Americans are having few children. The other reality is that 82 percent of America’s future population growth will be driven by immigration and births to immigrants.49

In a few short paragraphs the advertisers linked environmental destruction to overpopulation using per capita consumption arguments, and turned this into an argument for limitations on migration into the US. The crude, though not uncommon, basis to this argument might be that immigrants from Mexico, which has per capita emissions of 3.9 tonnes of carbon dioxide, would emit more when they arrived in the US, where per capita carbon dioxide emissions are 15.5 tonnes. Yet, the reality is that immigrants to the US are most likely to be poor and thus have the lowest impact on the environment. By implying that immigrants have more children (a common racist trope about people from the Global South), this rhetoric ignores that fertility rates among immigrant communities tend to decline in subsequent generations.

In Britain in 2019, a year marked by big environmental protests and climate strikes, a far-right group posted fake Extinction Rebellion stickers with slogans like “Third World Over-breeding Destroys the Planet”, “Only White People Care About the Environment” and “Sink the Boats, Save the World”. Although the group that produced these is tiny, the slogans reflect a wider racist narrative that uses overpopulation arguments to blame environmental destruction on those least responsible for it. In his history of anti-immigrant ideas in the US environmental movement, John Hultgren identified two different phases of this rhetoric. Between the late 1800s and the late 1930s, a romantic and Darwinian understanding of nature was linked to a “racial nationalism” through a “shared commitment to natural and national purity”. From the 1940s to the 2000s, neo-Malthusianism enabled “restrictionists to reinforce American sovereignty through the exclusion of immigrants”.50 For the far right and fascists, these ideas perfectly dovetail with racist fears about “replacement” of white populations.

In fact, countries in the developed world facing aging populations and declining birth rates will need immigration to provide labour in the future. Already immigration is a significant contribution to population levels in the Global North. Between 2005 and 2010, for instance, 70 million babies were born in “developed countries’’, while immigration added a further 17 million people, thus making up nearly 20 percent of “new arrivals’’. Immigration in these years has become a “very significant—indeed, structural—element of the rich world’s economic and social systems” despite increased attempts by governments to restrict migration.51 In many European countries, total population would fall without immigration. In Italy, population decline would be very dramatic were there no new migrants, with numbers falling from 61 million to 45 million by 2050.52

In the US, “restrictionist” individuals and groups have attempted to take over mainstream environmental organisations to push an anti-immigrant argument about overpopulation. Hultgren documents the intense arguments over migration within the Sierra Club, one of the largest and oldest American environmental organisations, as right wingers attempted to force it to take anti-migrant positions. The Southern Poverty Law Centre warned that “the Sierra Club, is the subject of a hostile takeover attempt by forces allied with anti-immigration activist John Tanton and a variety of right-wing extremists”.53 In 1998, this battle culminated with members of the Sierra Club narrowly agreeing to reassert their “neutrality” on the question. However, by the early 2000s, when the Sierra Club again faced anti-immigration lobbying, it had already taken a more progressive position of “showing up in solidarity with immigrant communities and organisations advocating for immigrant rights”.54

The initial vulnerability of the Sierra Club to anti-immigration hijacking lay in their earlier negative position on immigration and racism. In 1980, the Sierra Club’s Population Committee had recommended that “immigration to the US should be no greater than that which will permit achievement of population stabilisation”.55 In 2018, Hop Hopkins, the Club’s Director of Organisation Transformation, explained the roots of the support for anti-immigrant ideas among its membership:

It is a reflection of our exclusionary history and one marker of the environmental movement’s problematic overlap with the ideologies and activist members of population control, eugenics, and conservative movements. An example of this exclusionary history is the fact that the Angeles Chapter of the Sierra Club in southern California had a policy against allowing African American members in the 1950s.56

The Sierra Club was not unique in having these sorts of positions. Hultgren argues that the weakness of some US environmental organisations on the question of immigration and population stems from their incorrect understanding of how the environment is linked to wider social, political and economic issues:

The movement has struggled to come to terms with the complexities of nature, political community, political economy, race, class and gender, which the dominant articulations are unable to adequately represent. They illustrate a disconnect between the models of sovereign power that inform ecological action and the actually existing structures of authority that any effective and ethical socio-ecological resistance must engage.57

Debates in contemporary movements show that these arguments remain important. One example is the internal discussions within Extinction Rebellion about adopting a “fourth demand” focused on social justice. This is an explicit attempt by activists within Extinction Rebellion to acknowledge the historical legacy of colonialism and imperialism, as well as contemporary racism, sexism and social inequality, as part of a wider understanding of the structural causes and consequences of ecological destruction.58

Overpopulation arguments can fuel racist ideas, and the far-right uses and abuses the population issue. However, we should also note that overpopulation arguments can fuel right-wing policies in a more general sense. Paul Ehrlich, for instance, argued in 1970:

The US should withhold all aid from a country with an expanding population unless it convinces us that it is doing everything possible to limit its population… Extreme political and economic pressure should be placed on any country or international organisation impeding a solution to the world’s most pressing problem. If some of these measures seem repressive, reflect on the alternatives. 59

Indeed, overpopulation theories became central to the US foreign policy in the post-war period. The US ruling class feared that population growth would lead to food shortages that could fuel revolutionary movements. Their launch of the “Green Revolution” was an attempt to forestall “red revolution” through the transformation of the food system to increase crop yields and other outputs. Nevertheless, the Green Revolution also meant the transformation of the food system to an industrial, US-centric model. John Bellamy Foster describes this as the “commercialisation of land in the Global South using the model of US agribusiness—a ruthless form of ‘land reform’ (that is, land expropriation) that was legitimated by reference to Malthusian population tendencies”.60

Population growth, capitalism and the environment

Capitalism is a fossil fuel system. Fossil fuels, as Andreas Malm has shown, became the energy source of choice for the capitalist class because they allowed them to break free from the geographical restrictions imposed upon them by their previous reliance on water power. Crucially, this also gave the capitalist class access to urban workforces.61 Once one group of capitalists began to use fossil fuels, capitalists everywhere followed, ensuring fossil fuels became integral to the workings of the system. In 2019, the US produced 63 percent of its energy from burning fossil fuels. Global energy generation, and its transportation, is responsible for almost three quarters of greenhouse gases pumped into the atmosphere.

It is important that we do not reduce capitalism’s environmental destruction simply down to fossil fuels. Even a hypothetical capitalism based on renewable energy would be environmentally destructive because capitalism has an unsustainable relationship with the natural world. John Bellamy Foster has shown that Marx understood that capitalism had created an irreparable fissure in the metabolism between human society and nature. This “metabolic rift” exists because capitalism is a system of production only interested in maximising profit, and it can only be healed through the rational organisation of the relationship between society and nature.62 Environmental degradation is inherent to capitalism precisely because nature is embedded into capitalist production.

We emphasise this because it is key to comprehending why the overpopulation argument is wrong. We can understand this further by observing that those who link overpopulation to environmental issues often focus on per capita emissions: the figure calculated by looking at the total emissions from a country and dividing by total population. Concentrating on per capita emissions obscures more than it clarifies. Such figures hide regional differences in emissions, as well as variations between industries and between urban and rural areas. Most importantly, they disguise the role of class.

Take Britain, for example, where carbon dioxide emissions were around 5.8 tonnes per person per year in 2016.63 Compare this with countries like Syria (1.7 tonnes), Uganda (0.1 tonnes) and India (1.8 tonnes). It seems logical to argue that population growth in Britain—and other industrialised countries such as US (15.5 tonnes), Australia (15.5 tonnes) and Germany (8.8 tonnes)—will have a much more detrimental effect on the environment in terms of emissions than in the Global South.

What all this hides, however, is the enormous difference in emissions caused by people within countries in the Global North. To take one example, a recent study showed that just 1 percent of people were responsible for 50 percent of global aviation emissions in 2018.64 Of course, as the Guardian coverage points out, there are marked regional differences: “North Americans flew 50 times more kilometres than Africans in 2018, 10 times more than those in the Asia-Pacific region and 7.5 times more than Latin Americans. Europeans and those in the Middle East flew 25 times further than Africans and five times more than Asians.” Nevertheless, the bulk of emissions within Britain, Europe and the US come from “frequent flyers”. The air travel of this group were “equivalent to three long-haul flights a year, one short-haul flight per month, or some combination of the two.” In the US and Britain, around 50 percent of people made no flights at all. Most emissions from passenger aircraft are caused by a wealthy minority.

A crude “populationist” argument based on per capita emissions from flights would suggest that a general increase in the population of, say, Britain would lead to a proportional increase in the amount of emissions from flying. Yet, this ignores the difference in numbers of flights made by rich and poor people. Unfortunately, the per capita approach to emissions allows overpopulation theorists to generalise about whole populations and sheer numbers of people.

This approach has attained a veneer of scientific plausibility through the infamous IPAT equation. This formula suggest that environmental impact (I) is equal to population size (P) multiplied by affluence (A) and technology (T). This installs population size as one of three determining factors for environmental destruction. The more affluent, technological and populous a society is, the more environmentally destructive it is. The IPAT equation was put forward in its earliest form by Ehrlich and John P Holden in their attack on the work of radicals such as Commoner. In a 1971 paper, Ehrlich and Holdren argue against a set of what they called “questionable assertions”:

Perhaps the most serious of these is the notion that the size and growth rate of the US population are only minor contributors to this country’s adverse impact on local and global environments.65

In contrast, the authors propose five “theorems”. The first argues, “Population growth causes a disproportionate and negative impact on the environment”:

Population size influences per capita impact in ways other than diminishing returns. As one example, consider the oversimplified but instructive situation in which each person in the population has links with every other person—roads, telephone lines and so forth. These links involve energy and materials in their construction and use. Since the number of links increases much more rapidly than the number of people, so does the per capita consumption associated with the links.66

Ehrlich and others developed these arguments in further papers, but the scientific veneer given to the IPAT equation in these writings falls apart under scrutiny. As Ian Angus and Simon Butler explain:

In fact, IPAT isn’t a formula at all—it is what accountants call an identity, an expression that is always true by definition. Ehrlich and Holdren didn’t prove that impact equals population times affluence times technology; they simply defined it that way. 67

Angus and Butler go on to show how IPAT, despite coming to define an entire approach to population debates, has also had a series of powerful rebuttals. They quote Patricia Hynes, who concludes in her 1993 article, “Taking Population Out of the Equation: Reformulating I=PAT”, that the equation is based on a “singular view of humans as parasites and predators on the natural environment”.68

To understand further the problems with the IPAT approach, let’s look at how Ehrlich uses similar arguments to explain a contemporary environmental issue, smog in Los Angeles, in his 1971 book The Population Bomb. He argues that the growth of the city’s population led to more cars and thus more exhaust fumes:

In Los Angeles and similar cities the human population has exceeded the carrying capacity of the environment—at least with respect to the ability of the atmosphere to remove waste. Unfortunately, Los Angeles smog laws have just barely been able to keep pace with their increasing population of motor vehicles (the main source of the smog). And it seems unlikely that much improvement can be expected in this aspect of air pollution until a major shift in our economy takes place… Unless a lot more effort is put in on perfecting and producing devices to restrict smog output, the growing population of motor cars should keep Los Angeles and similar cities unfit for human habitation.69

Ehrlich knows that there are changes that can be made to reduce pollution. For instance, he says “factories and motor cars can be forced to meet standards of pollutant production”.70 Still, he wrongly locates the source of the problem. The growth in car use was not to do with increased population but more complex issues. As Angus and Butler explain while discussing the work of environmental sociologist Alan Schnaiberg:

Between 1960 and 1970, US population increased by 23.8 million, and private automobile ownership increased by 21.8 million. A populationist model would conclude that more people equaled more cars. However, there is a major logical flaw in that reasoning. Population growth between 1960 and 1970 was almost entirely made up of children born in that decade, none of whom were old enough to buy cars.

Angus and Butler explain Schnaiberg’s conclusions:

So the increase in cars was caused not by more people or more families, but by some families buying more than one car… Families with no car tended to be older, poorer and urban, while those with two cars tended to be middle aged, better off, and suburban or rural.

Schnaiberg suggests that the increase in cars was related to an increase in women entering the workforce.71 As Angus and Butler’s summary of Schnaiberg’s work shows, the growth in car use was a secondary result of wider social, political and economic changes. This can clearly be seen in the case of Los Angeles.

Until the 1950s, Los Angeles had been a city served by an extensive electric tram network. As the city grew, planners wanted to expand the suburbs, but they did not expand the tram system. A massive road network was built and public transport companies switched from trams to buses. Thus, the growth of the city led to more smog, not because of population growth, but because transport became geared towards cars and buses over other less polluting alternatives.

The example of transport in Los Angeles demonstrates that correctly understanding changes in environmental pollution means moving away from superficial relationships between numbers of people and volumes of pollution. Trying to understand environmental destruction using equations such as IPAT means that we ignore the nature of capitalism itself. For instance, the US military produces the same amount of emissions as 140 countries combined. As one journalist points out, “The Pentagon would be the world’s 55th largest carbon dioxide emitter if it was a country”.72 However, the scale of the US military is not a function of the country’s population—it is a consequence of the US’s post-war global economic dominance and its imperial ambitions.

Population is not “one strand” in political argument. It is a rhetorical distraction from the real argument. Focus must be kept on the system of capitalist production, not the way that individuals consume. Capitalism has always created new demands and markets; this is necessary because the anarchic market system tends to overproduce commodities. The problem is not an increased number of people buying and consuming more, but a system that has inefficiency, waste and fossil fuels at its heart.

Conclusion

Those who argue that the world is overpopulated do not always come from the right. However, the dominant argument about population is one that stems from a right-wing view of society. From this perspective, ecological disaster, unemployment, poverty and hunger arise from the aggregate sum of individual choices, not structural problems of capitalism. In contrast, socialists do not argue that numbers are irrelevant, but that the environmental impacts of our species and its numbers are dictated by societal form, and that the enemy is a system that places the accumulation of capital before people and planet. That is why Marx and Engels attacked Malthusian politics with such vigour. They understood that these arguments, by placing the blame on the masses, end up diverting anger away from capitalism. This is not to say that a socialist society could increase human population indefinitely with no negative consequences. We can be confident that this would not happen. Revolutionary transformation and the creation of a society organised on the basis of human need would lead to an associated transformation of human demographics.

Capitalist production fuels ecological destruction because it is driven by an unrelenting quest to accumulate more wealth in the hands of capitalists. The organisation of production under capitalism has concentrated wealth in the hands of a tiny minority, at the same time as concentrating workers in urban areas, factories and other large-scale workplaces. The irrational organisation of production leads to the depopulation of rural areas in favour of cities. In this way, capitalism constantly creates and recreates unsustainable social relations that will need to be transformed if there is hope of a sustainable future.

Marx and Engels were clear that a socialist society would allow a more rational organisation of humanity’s relationship to our environment. As one of their ten demands in the Communist Manifesto, they called for the “gradual abolition of the distinction between town and country by a more equable distribution of the populace over the country.”

Capitalism’s unsustainability hides the real relationship of population to the environment. A socialist society would transform our relationship to nature and create a new, sustainable way of organising production. This, as Angus and Butler point out, might finally allow us to “measure Earth’s carrying capacity scientifically”.73 Indeed, were it conducted in a world where the corrupting profit motive had been replaced, we may be pleasantly surprised by such an exercise. However, to achieve such clarity we must get rid of capitalism. The first vital step in achieving that requires focusing on the system, not giving grounds to arguments that maintain the capitalist status quo by placing the blame for our societal ills on the masses.

Today, millions of people understand that capitalism is leading the world to catastrophe. We must fan the flames of the growing rebellion without conceding to the idea that ordinary people, their reproductive rights and their decisions over childbearing are to blame. Our alternative is a society based on a rational organisation of the relationship between humans and nature, where production is democratically planned by what Marx called the “associated producers”. Getting there means we must begin by siding with the oppressed and highlighting the real enemy: capitalism.

Martin Empson is the author of Kill all the Gentlemen: Class Struggle and Change in the English Countryside (Bookmarks, 2018) and the editor of System Change not Climate Change: A Revolutionary Response to Environmental Crisis (Bookmarks, 2019).

Ian Rappel is an ecologist and member of the SWP. He was a lecturer in Population Studies at Cardiff University during the 1990s.

Notes

1 Barry, 2007. We would like to thank Ian Angus, Joseph Choonara, Sheila McGregor, Laura Miles, Camilla Royle and Neil Thomas for their helpful comments on drafts of this article.

2 Gates, 2021; Holmes, 2012.

3 Attenborough, 2020.

4 Webb, 2020

5 For a recent example of this, see Dasgupta, 2021.

6 Melia, 2021, p208.

7 Carrington, 2019.

8 Thornett, 2019, p133. Thornett’s estimations are actually below those calculated by the United Nations, which predicted a 2050 figure of 399 million in its 2015 report, and 401 million in its 2019 report. See United Nations, 2015, p31; United Nations, 2019a, p15.

9 Thornett, 2019, p161.

10 For an introduction to Malthus’s life and ideas, see Reisman, 2018, pp1-25.

11 Davis, 2002, p32.

12 It should be noted that Malthus was building on the earlier, but today largely forgotten, arguments of Robert Wallace. In 1761, Wallace published Various Prospects of Mankind, which argued that an egalitarian society was impossible because inevitable population growth would outstrip available resources. See Reisman, 2018, p41 and Foster, 2002, pp138-139.

13 Malthus, 1970, p72.

14 Malthus, 1970, p134.

15 Malthus, 1826, p340.

16 Malthus, 1826, p424.

17 Quoted in Thomas, 2019, p80. Richard Gough Thomas’s book on William Godwin is an excellent introduction to the ideological and political atmosphere in which Malthus and Godwin wrote. Godwin’s initial engagement with population debates was in response to Wallace and Malthus’s Essay was in reply to Godwin’s critique of this earlier work. See Foster, 2002, p139.

18 Thomas, 2019, pp80-81.

19 Thomas, 2019, p128.

20 Engels, 1982, p309.

21 Engels, 1982, p309.

22 A good critical summary of Malthus’s economics, and Marx and Engels’s response, can be found in Meek, 1971, pp16-26.

23 Quoted in Reisman, 2018, p204.

24 Quoted in Reisman, 2018, p227.

25 From Theories of Surplus Value, volume 3. Quoted in Meek, 1971, p33.

26 Meek, 1971, pp16-17.

27 Marx, 1977, p606.

28 Marx, 1977, p606.

29 Foster, 2002, pp146-147.

30 Marx, 1977, pp606-607.

31 Marx, 1990, pp783-784.

32 Quoted in Meek, 1971, p60.

33 The Green Revolution vastly increased agricultural productivity, but its emphasis on technology and chemical inputs had huge social and ecological impacts. Closely linked to the Green Revolution was the expansion of industrialised agriculture from the US to the Global South. This undermined existing farming methods in the Global South, tying peasant and small-scale producers into a global food economy geared towards maximising the profits of multinational food producers primarily based in the Global North. For more on this, see Leather, 2021, pp30-32.

34 Meek, 1970, p87.

35 Burkett, 1998, p140.

36 Meek, 1971, p120.

37 Burkett, 1998, p136.

38 Foster, 2002, pp150-151.

39 United Nations, 2019b.

40 McCurry, 2021; Yu, 2021.

41 United Nations, 2019b.

42 Rappel and Thomas, 1998.

43 Thomas, 1995.

44 Kim, 2016.

45 Kim, 2016; Roser, 2017; Thomas, 1991.

46 A humane approach to population management might involve applying the lessons in social development that led to rapid birth rate declines in Cuba and the state of Kerala in southern India. See William Murdoch’s seminal work in this area—Murdoch, 1980.

47 For more on contemporary “eco-fascism” and its long history see Sparrow, 2020 and Hultgren, 2015.

48 Commoner, 1971, p233.

49 See the image of this advert in Hultgren, 2015, p15

50 Hultgren, 2015, p25.

51 Bacci, 2017, p46.

52 Bacci, 2017, p49.

53 Quoted in Hultgren, 2015, p50.

54 Hopkins, 2018.

55 Hultgren, 2015, p46.

56 Hopkins, 2018.

57 Hultgren, 2015, p144.

58 The text of the fourth demand adopted by Extinction Rebellion US reads: “We demand a just transition that: prioritises the most vulnerable people and Indigenous sovereignty; establishes reparations and remediation led by and for black people, Indigenous people, people of colour and poor communities for years of environmental injustice; establishes legal rights for ecosystems to thrive and regenerate in perpetuity; and repairs the effects of ongoing ecocide to prevent extinction of humans and all other species, maintaining a livable, just planet for all.”—https://extinctionrebellion.us/demands

59 Quoted in Commoner, 1972, p241.

60 Foster, 2002, p149. For analysis of the ecological and social impacts of the Green Revolution, see Shiva, 2016.

61 Malm, 2016.

62 See Foster and Clark, 2020 for a recent reassertion of these arguments.

63 All per capita figures taken from World Bank databank—https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EN.ATM.CO2E.PC

64 Carrington, 2020.

65 Ehrlich and Holdren, 1971, p1212.

66 Ehrlich and Holdren, 1971, p1213.

67 Angus and Butler, 2011, pp47-48.

68 Quoted in Angus and Butler, 2011, p49. This erroneous and simplistic view of human ecological impacts has been discussed previously in this journal—see Rappel, 2021.

69 Ehrlich, 1971, p66.

70 Ehrlich, 1971, pp66-67.

71 Angus and Butler, 2011, pp38-39.

72 McCarthy, 2019.

73 Angus and Butler, 2011, p62.

References