Along with 10.1 million other viewers, I awaited 10pm on 12 December last year and the broadcasting of the BBC/Sky/ITV general election exit poll of voters. “Here we go,” I anxiously WhatsApped a friend as the time-signal sounded. Ten seconds later he replied: “Fuck”. The poll was not entirely accurate, overstating both the Tory and Scottish National Party (SNP) gains. However, it was immediately apparent that, unless there was some historic error in its findings, we were not going to see a Labour Party led by Jeremy Corbyn evict Conservative prime minister Boris Johnson from Downing Street.1 When the full results were in, the grim reality was confirmed—Conservative 365 MPs, Labour 203, SNP 48, Lib Dems 11. Boris Johnson enjoys the first big majority for a governing party since 2005—the first for the Conservatives since 1987.

Why did it happen? Understanding this is not some academic exercise. Millions invested massive hope in a Corbyn victory. Some of this was overblown, exaggerating the radicalism of Labour’s programme. But Corbyn did reflect the yearning for an end to a decade of cruel austerity, a hunger for a different sort of politics, no longer centred on the priorities of big business and the rich. Instead it was an electoral disaster for Labour. Many on the Labour right—who preferred a Tory victory to a Corbyn one—are using the result to demand a return to the “centre”, precisely the politics that have proved disastrous in Britain and many other parts of the word. It is also being used by opponents of socialism across the world. Joe Biden, former US vice president and challenger for the Democrat nomination for the 2020 presidential election, pointed to Labour’s defeat as a warning of what happens if you go too far to the left—by which he meant Bernie Sanders and even Elizabeth Warren. “Boris Johnson is winning in a walk,” Biden said as the results came in. He told supporters that international headlines the next day would read: “Look what happens when the Labour Party moves so, so far to the left.”2

The British voting system accentuates the scale of the shift. There was no massive increase in the Tories’ vote. It was up only 1.2 percent on 2017. They gained 300,000 votes in 2019 compared with Theresa May’s increase of 2,000,000 in 2017. There are no Tory MPs in Bradford, Bristol, Cardiff, Coventry, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Hull, Leeds, Leicester, Liverpool, Manchester, Newcastle, Nottingham or Sheffield. In London, the Tories gained two seats and lost two, and still have just 21 of the capital’s 73 MPs. When the Conservatives won in 1987, they had more than two-thirds of London’s MPs.3

Nevertheless, Labour’s defeat is serious. The tally of 203 seats is Labour’s lowest since 1935:

Looking at the last century, only in 1983 has an opposition lost more seats than Labour did last night. Crucially that was after only four years of Margaret Thatcher’s government, whereas the Conservatives have now been the incumbents for nine long years—by now the public tend to fancy a change. Clever clogs might say that Labour lost by ten percentage points in 1987 after an almost comparable eight years of Conservative rule. But even then Labour didn’t lose seats and the economic backdrop was very different to today. For those people and places not scarred by unemployment, 1987 was boom time Britain. Today, our economy is hardly growing and earnings are only just returning to their pre-crisis level a full decade on.4

It is also true that Labour received only 455,000 fewer votes in 2019 than 18 years earlier (10,269,000 in 2019 compared with 10,725,000 in 2001 when Tony Blair won a majority of 166). Labour’s vote in 2019 was higher than in 2005, 2010 and 2015. The story of 2019 is a fall in Labour’s vote compared with 2017, not a soaring Conservative vote. The big picture is that 2019 saw Labour return to a trend of stagnation and decline that has been apparent for decades—a trend that was bucked only by Corbyn’s message of hope and transformation in 2017. As Labour’s vote slumped by 2,500,000 in 2019 it was not plumbing new depths but returning closer to the total won by former Labour leader Ed Miliband in 2015. One analyst writes, “2019 was not an earthquake but a tipping-point”.5

Did the poor vote for the toffs?

When looking at class and voting it is important to start with a health warning. For Marxists, class is not an individual or subjective attribute defined by where you come from, what sort of accent you have or what individual consumer choices you make. It is a social relationship. The capitalist class owns and control the “means of production”—the offices and computers, call centres and phones, factories and machinery. Because working class people do not own these things, they have to sell their labour power, their ability to work, in return for a wage. Postal workers and cleaners are part of the working class, but so too are most teachers and university staff.

Most pollsters, by contrast, use the National Readership Survey (NRS) social classification grades. These are based on occupation and are widely used in market research. Table 1 shows the grades and what percentage of the population falls into each. These classifications are not the same as class divisions; they can, at best, paint a very broad picture of the relation between class and the vote. Every group except A includes large numbers of workers. The B group, for example, includes some lecturers, teachers and health workers.

Table 1: Breakdown of UK population among NRS grades

Source: NRS, 2020.

|

Grade |

Occupations |

% |

|

A |

Higher managerial, administrative and professional |

4 |

|

B |

Intermediate managerial, administrative and professional |

23 |

|

C1 |

Supervisory, clerical and junior managerial, administrative and professional |

28 |

|

C2 |

Skilled manual workers |

20 |

|

D |

Semi-skilled and unskilled workers |

15 |

|

E |

State pensioners, casual and lowest grade workers and unemployed with state benefits |

10 |

Therefore, polling using the NRS grades should be used with care, and this is intensified by the way pollsters act and the nature of who votes in capitalist society—a third of eligible people did not vote at all in the 2019 general election. In addition, even after the surge in 2019 registration, around 30 percent of 18 to 34 year olds are not registered to vote and millions of others are not registered or wrongly registered.6 As table 1 shows, categories A and B together make up 27 percent of the population, but the Ashcroft poll is made up of 42 percent people in A and B—because they are more likely to vote.

Another problem is seeking to measure election outcomes over many years against particular social groups when those groups may go through important changes. A recent article by Michell and Jump looks at one study that “uses vote shares from the 2010, 2015, 2017 and 2019 general elections, but only uses data on blue-collar occupation shares from the 2011 census. The figure therefore ignores any changes in the populations of blue-collar workers since 2011”.7

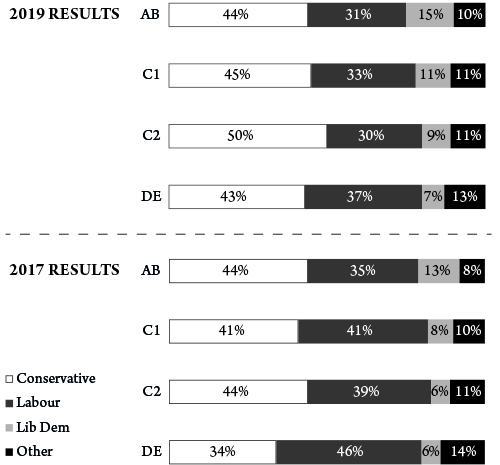

With all those caveats, we can still compare similar analyses at different elections. The breakdown from Ashcroft’s poll for the 2019 and 2017 elections are shown in figure 1.

Figure 1: Breakdown of vote among NRS grades, 2017 and 2019

Source: Ashcroft, 2019.

The Tory vote is almost unchanged in category AB. It is significantly up in C2 (six points) and DE (nine points). Labour’s vote is down in all categories, but the biggest fall is among C2 and DE (nine points each). The inescapable conclusion is that numbers of working class people who had voted for Corbyn’s Labour Party in 2017 changed their vote this time.

Some of them voted Tory; some abstained; some voted for other parties. The precise flows are hard to gauge because you cannot be sure that if one party’s vote in the DE category goes down nine points and another goes up nine points that there has been a simple transfer. A 2017 Labour voter might have switched to the SNP, or the Lib Dems. A UK Independence Party (UKIP) voter might have chosen the Tories this time. However, the overall trend is clear.8

We can also look at the detailed tables based on income from some of the post-election analyses. Among full-time workers, Labour was 2 percent behind the Tories in 2019. In 2017 Labour had been 6 percent ahead. But, in what comes as a bigger shock, the Tories led Labour by 11 percent (45 to 34) among people with a household income of less than £20,000. Even worse, in households with an income of between £20,000 and £40,000 (most of which must be people in work) the Tories led Labour by 47 percent to 31 percent—a gap of 16 percent. The Tory lead was actually more slender among households with an income of over £70,000.9

There are some important counter-trends. The Tories have not become the party of the poor. Figure 2 shows the party vote relative to the relative deprivation of a constituency. There is still a clear correlation: poorer areas tend to vote Labour; richer ones, Tory.

Figure 2: Relationship between deprivation and Conservative/Labour vote, English constituencies, 2019

Source: Commons Briefing Paper CBP-7327; House of Commons Library, 19 December 2019.

However, a more detailed analysis by the Resolution Foundation, comparing the 2019 result with those of earlier elections, demonstrates a weakening of this relationship between deprivation and voting Labour between 2017 and 2019.10 In 2017 Labour’s vote share in the most deprived constituencies was around 65 percent. Two years later it was down to just over 55 percent—although that is still above the figure for 2010. More generally, if we look at the most deprived constituencies in England, the top 16 are all Labour seats—and all are in the North of England or the Midlands.11 You have to get to number 17 on the list (Blackpool South) before there is a Tory gain. The working class has not “gone Tory” but some people have, and crucially they are concentrated in seats that were key in the 2019 election.

The role of Brexit

The immediate cause of Labour’s defeat in England and Wales was its position on Brexit and the European Union (EU). Labour lost 54 seats to the Conservatives and all but two had Leave majorities in the 2016 EU referendum.12 In those seats where more than 60 percent of voters backed Leave in the referendum, the average increase in Conservative support was 6 percent. Labour’s vote in these seats was down 10.4 percent.

Here are three examples. In Bolsover—former Labour MP Dennis Skinner’s seat, which voted by 70 percent for Leave in 2016—the Labour vote was down roughly 8,000. The Tory vote increased by about 3,000 and the Brexit Party took about 4,000—2,000 more than Ukip in 2017. Some who voted for other parties or who abstained last time voted Tory this time but it is also reasonable to assume that there are thousands of 2017 Labour voters who did not vote at all this time. It is reasonable to speculate that they did not feel motivated to vote Labour but could not bring themselves to vote for anyone else. In Workington—61 percent Leave—the Labour vote was down about 5,000 votes from 2017. The Tories were up 3,000 and the Brexit Party vote was only just above what UKIP took in 2017. Again it seems reasonable to argue that some former Labour voters did not vote, and indeed the percentage turnout was down. A final example is Blyth Valley—60 percent Leave and one of the most commented on seats at the 2019 election. The Labour vote was down around 7,000. The Tories were up just 1,500. The Brexit Party took 3,400—and probably quite large numbers of Labour voters stayed home.

Why such a consistent pattern across many constituencies? A YouGov study in January explored the views of voters who had switched from Labour to the Tories, finding:

Half (49 percent) said it was down to Brexit. This came above the leadership of the parties (27 percent) and the wider policy offering (10 percent)… There is a real feeling among these voters that the Labour Party has left them behind. In total, 74 percent think “Labour used to represent people like me, but no longer does”. In total, just 12 percent of Lab-Con switchers think the Labour Party is close to people like them.13

In contrast Johnson had a clear plan from when he became leader. It was to present himself—wholly falsely—as the friend of the Leave-voting masses, and a sturdy opponent of the elitism and privilege that was squashing their voices. His slogan of “Get Brexit Done” won out. The detail of the main YouGov analysis of the election showed that just 52 percent of those who had voted Leave and then voted Labour in 2017 stayed with Labour in 2019. A third of them voted Tory.14

As a final piece of evidence, look at the constituencies with the biggest declines in Labour’s vote share. These were also heavily Leave-voting areas:

- Wentworth and Dearne, down 25 percent (70 percent Leave)

- Bassetlaw, down 25 percent (68 percent Leave)

- Barnsley Central, down 24 percent, Barnsley East 22 percent (Barnsley was 68 percent Leave)

- Doncaster North, down 22 percent; Doncaster Central, down 18 percent (Doncaster was 69 percent Leave)

- Normanton, Pontefract and Castleford, down 22 percent (69 percent Leave)

- Jarrow, down 20 percent (62 percent Leave)

Over the two years preceding the election, Labour has edged closer and closer to a Remain position and has called for a second referendum. This was a major shift from its 2017 manifesto policy, which stated: “Labour accepts the referendum result and we will seek to unite the country around a Brexit deal that works for every community in Britain.” The new approach was disastrous. It alienated swathes of those who voted Leave. Tariq Ali put this pithily: “Let’s face it: Johnson won the election because the Tories pledged to implement the result of the 2016 referendum without any more shilly-shallying. Democracy matters. Labour’s rejection of the referendum outcome at its bubble party conference last September did them in”.15

Political responsibility for the Labour shift to support a second referendum begins with figures such as shadow Brexit secretary Sir Keir Starmer and shadow foreign secretary Emily Thornberry. They were backed by union leaders such as Tom Roache of the GMB and the Trade Union Congress’s Frances O’Grady. But the responsibility goes wider. At a People’s Vote rally in October 2019, shadow home secretary and Labour left-winger Diane Abbott told the crowd: “I’m a Remainer.” Shadow chancellor John McDonnell also spoke, saying: “We believe that our future best lies within the European Union itself.”

Most of Labour’s right, motivated by the concerns of business, had relentlessly put forward an argument for overturning the Brexit vote via a second referendum. Dragging Labour closer to this position was achieved through pressurising Corbyn—and through his compromises. At the 2018 party conference, it was overwhelmingly agreed that a fresh public vote had to be kept “on the table”. By July last year, following a shadow cabinet meeting, Corbyn wrote to party members to say Labour would campaign for Remain “against either no-deal or a Tory deal”. And he called on the next government to hold a second referendum before exiting the EU.

The “left exit” (Lexit) position of fighting for a workers’ Brexit was derided by many in Labour, but it was the correct position. It meant a radical critique of the EU from the left, based on internationalism, anti-racism, anti-capitalism and a fight for real democracy. Instead of attacking the EU for allowing in too many migrants as the right did, socialists should have pointed to its lethal “Fortress Europe” policy that led to drowned migrants and refugees. Lexit supporters said the true nature of the EU was revealed by its financial squeeze on Greece after the election of Syriza in 2012.16

Labour also allowed Brexit to be separated from all the other class issues—the NHS, housing, Universal Credit, jobs, education, climate chaos and so on. Instead, the impoverished imagination of far too many union leaders and Labour MPs led to Brexit being hived off into a wholly divisive area abstracted from all those where the Tories were weak. In a perceptive article written two months before the election, Sadie Robinson noted in Socialist Worker:

People had many reasons for voting Leave. But one of them was a deep dissatisfaction with mainstream politics and a desire to give the establishment a kicking. Three years on political leaders, bosses and others are still putting barriers in the way of leaving the EU. Many people have had enough. “I’m fed up of hearing about it,” said Joan, who works in a pawnbrokers in Doncaster, South Yorkshire. “It’s gone on too long now. I just want it to be sorted.” In Doncaster some 69 percent of those who voted in the EU referendum voted to Leave. Many now feel betrayed and let down by British “democracy”.17

A blog by Eyal Clyne, a Labour canvasser who campaigned in eight marginal constituencies in the north west of England, says:

Leave voters are sometimes seen as ignorant, brainwashed or racist, images that did not correspond with my impressions overall. However, for Leave voters, Brexit now symbolises the way in which their voices were being ignored, repeatedly and undemocratically, by the losing Remainers, who are also associated with other classes and more privileged groups… As far as they are concerned, Labour (and others) did not fully respect the will of the working class, and a democratic result. They feel betrayed.18

It is not just that many voters felt that Labour had betrayed them. The Brexit issue bled into other areas of policy. If Labour could not be trusted to implement the Brexit vote, how could they be trusted to carry though the raft of promises they were making now? Not credible on Brexit became not credible on everything. Analysing and understanding why workers were pulled to vote Tory or the Brexit Party is not to justify such a move or celebrate it. But it is no good simply denouncing them as ignorant dupes. These were people who could and should have voted against ruling class warrior Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson. In 2016, people who are generally forgotten, ignored or sneered at delivered a stunning blow against the people at the top of society. In 2019 Labour spurned them.

Of course, some people did vote Leave (and for Johnson or for Nigel Farage) for racist reasons.19 There is a serious problem of racist myths being widely accepted in society, including in parts of the working class. All the main political parties (including Labour until 2015) have spent years telling anyone who would listen that there are “too many” migrants coming to Britain and that they cause problems in terms of housing, jobs, wages and public services. Even Corbyn and his followers, such as Len McCluskey of the Unite union, repeated the idea that migrants force down pay in some sectors. Such ideas have to be confronted, not pandered to, but this cannot be done by simultaneously telling people their votes will be set aside or chortling at their alleged gullibility. You do it by showing how it is in their class interest to reject racism. It can only be done by linking anti-racism with a ferocious determination to wage the class war. This is one reason why the Socialist Workers Party rejected the idea that the way for Labour to regain the voters it lost was to become more racist and more nationalist. We must reject the idea that workers are a reactionary bloc. As Keenan Malik wrote:

The working class, runs the argument, is rooted in communities and cherishes values of family, nation and tradition. Labour now faces a choice: either accept that its traditional working class voters are gone forever or abandon liberal social policies. The trouble with this argument is that the key feature of Britain over the past half century has been not social conservatism but an extraordinary liberalisation. On a host of issues, from gender roles to gay marriage, from premarital sex to interracial relationships, Britain has liberalised. It’s not just metropolitan liberals but society as a whole, including the working class, which has embraced this change.20

What about Remainers?

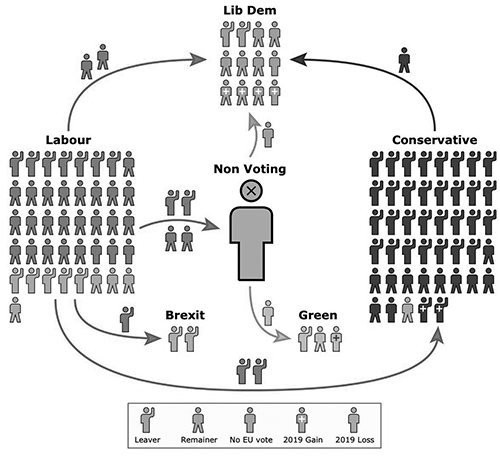

Some inside Labour now say that had Labour not adopted a second referendum policy they would have suffered an even greater drubbing. They also claim that Labour lost more Remainers than Leavers. The biggest single shift from Labour was to abstention from voting. Overall Labour lost five Leave voters to every four Remain voters (figure 3). Of course, we cannot know precisely what would have happened if Labour had stuck to its “respect the vote” position. The analysis above suggests Labour would have retained many of the seats it lost in the north of England and the Midlands. Perhaps it would have lost some votes in the most pro-Remain areas. However, in the three constituencies in the most pro-Remain area in Britain—Lambeth in south London—the Labour majorities in 2019 were 27,310 (Dulwich and West Norwood), 19,612 (Vauxhall) and 17,690 (Streatham). Even if Labour had lost a few thousand more votes, it would not have imperilled its majorities. There is, of course, an even stronger argument: respecting the referendum and not lining up with the neoliberal EU was the right thing to do.

Figure 3: Voter migration (raised hands represent Leave voters), 2017-2019

Source: Electoral Calculus.

“I don’t like Corbyn”

The polls show that lots of people said they did not vote Labour because of the leadership of Jeremy Corbyn. It is also true that millions of people voted for Labour because of Jeremy Corbyn. It was his promise of change that rescued Labour in 2017. So at first sight the feeling against Corbyn is strange—some who rejected him are people who had voted for him two years earlier on a similar manifesto. What did people in 2019 mean when they said they did not like Corbyn?

Certainly the Labour right encouraged voters to see him as extreme and outrageous. In Barrow and Furness, former Labour MP John Woodcock claimed that Corbyn “would pose a clear risk to UK national security as prime minister”. In Bassetlaw, John Mann—before resigning from the party and being made a baron—repeatedly called on Corbyn to step down. The outgoing MP for Dudley North, Ian Austin, called for a vote for the Tories. These three seats were all lost to the Tories. And of course the media waged the most brutal character assassination of Corbyn in particular and Labour in general. However, that does not explain the depth of the feeling.

The Labour blogger, Clyne, writes:

Surprisingly, only a relative few resonated the vilifications that they were fed through the media (like that he is a terrorist sympathiser, an extremist or an antisemite). It was more common to encounter a vague emotional negative hunch, a discomfort from the way they “felt” about him. For whatever reasons that they struggled to verbalise when asked, many explicitly “didn’t like him”, regardless of their strong rational agreement with his social policies. The media contributed to this image, sure, but if I may guess, I think that the voters did not want a “nice old man” who “never did any wrong”, almost inhumanely, who always engages in calm discussions, but would favour a more relatable and animated person, who gets angry sometimes (after all, we have much to be angry about), and whom is perhaps more dominant in conversations and offers simple messages, like Johnson or, better yet, Bernie Sanders. Remember that people vote more emotionally than rationally, as an expression of their identities and wishes, and, sadly, our leader, whose policies and personality were my own reasons for joining the canvassing, wasn’t popular with the masses.21

Corbyn could not escape the dither and slide of Labour’s Brexit position. Indeed his excruciating efforts to hold Labour’s position together but, in the end, swallowing a second referendum linked him to the feeling of betrayal over Brexit. This is not the whole story. There were elements of Labour’s campaign that could have been better. It should have centred on mass rallies and major public events open to all—as it did to a far greater extent in 2017. Instead there was a drive towards trying to implement a more “professional” approach, centred on canvassing. It was a much less insurgent and angry campaign than in 2017. It was more defensive, with Labour seeking to appear as a government in waiting, rather than any sort of movement for fundamental change. Corbyn himself should have been more confrontational with Johnson in the two televised debates, pinning the responsibility for the Grenfell fire, 130,000 deaths from austerity and Johnson’s foul racist and homophobic statements directly and personally on him. Labour could have had billboards across Britain and Facebook adverts recalling Johnson’s vile utterances—that the queen was routinely welcomed abroad by “cheering crowds of flag-waving piccaninnies”, that during a visit by Tony Blair to the Congo, the African warriors would all “stop their hacking of human flesh” and would welcome him with their “watermelon smiles”. More recently he claimed that the burka made the women wearing it look like “bank robbers” or “letterboxes”. Such assaults on Johnson would have forced him into a response. Either he would have had to retreat or to seek to justify what he had said. It would have heated up the atmosphere—and it would have been right to do it. As Gary Younge put it, “Time and again he had chances to nail Boris Johnson for his lies and duplicity, but he refused to do so. He’d say it’s not his style. But his style wasn’t working”.22

Instead Corbyn broadly stuck to the conventions of mainstream politics. In a terrible reversal of the truth, he often seemed closer than Johnson to an establishment position. When Johnson prorogued parliament in order to avoid scrutiny of his Brexit bill, Labour lined up with the mainstream acclamation of the Supreme Court and the veneration of its president Lady Hale. The judges’ finding, that Johnson had acted unlawfully, was celebrated by Labour. The Supreme Court’s role was not such an obviously good thing to lots of the voters who would later abandon Labour. A few months later judges said that the 97 percent vote by Royal Mail workers for a strike on a 76 percent turnout was not valid. One north London postal worker responded: “Judges! First they try to stop Brexit, then they stop our strike”.23 The two cases are not exactly the same, but it is easy to see that Labour did not gain with many Leave voters by lining up with the courts.

This sense of Labour looking like the political establishment was intensified by Labour-led councils meekly imposing austerity for a decade. The Tories have savaged local budgets. The Institute for Fiscal Studies claims spending on services in England fell by 21 percent between 2009-10 and 2017-18. The cut in their core funding from government is over 40 percent. The result has been horrendous attacks on key services. Yet Labour councils have not offered any serious response—and in many cases have made working class people pay the price of austerity. If you are in Durham, an area where Labour lost out at the election, one of the strongest memories for tens of thousands of people was the Labour county council slashing the pay of nearly 3,000 teaching assistants.

Antisemitism slurs and party democracy

Another big Corbyn-themed issue was antisemitism. For more than four years the lie has been peddled that Labour, and Corbyn in particular, are antisemitic. A tiny number of Labour members have made antisemitic comments or have antisemitic views, although as a proportion far less than is true of the general population. All such examples need to be confronted. Instead, lies about Labour’s “institutional antisemitism”, and Corbyn allegedly acting as a magnet for all those who hate Jews, were deployed for political gain. The slurs began during the 2015 leadership campaign and soon developed into a full-scale assault. This process began with attacks from the Labour right, and was quickly joined by most of the media, supporters of Israel and then the Tories. It was a grotesque reversal of reality—in the case of the Tories’ attack on Corbyn it was racists smearing an anti-racist as a racist. It is the Conservatives who have actively cooperated with real antisemites such as Hungarian leader Viktor Orban.

However, instead of angrily refuting claims that it was antisemitic, Labour made concession after concession towards its critics. Anti-racist activist Marc Wadsworth was expelled, Chris Williamson MP suspended and Ken Livingstone driven out of the party—while Tony Blair remained. The party adopted the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance definition of antisemitism and its examples. This meant accepting it is antisemitic to describe the state of Israel as “a racist endeavour”. It outlawed Palestinians from describing their oppression as racist. None of this halted the tirade of attacks. Predictably, it encouraged critics to demand more and more. During the election campaign the antisemitism slurs came back with added venom. Two weeks before election day, chief rabbi Ephraim Mirvis said Corbyn’s claims to be tackling antisemitism in his party were a “mendacious fiction”. He added, “A new poison—sanctioned from the very top—has taken root in the Labour Party.” Not to be outdone, Justin Welby, the Archbishop of Canterbury, tweeted that rabbi Mirvis’s “unprecedented statement at this time ought to alert us to the deep sense of insecurity and fear felt by many British Jews”.24 Corbyn’s refusal to confront these lies head-on simply added to his image of weakness.

More fundamentally, he had also spent four years failing to carry through any sort of attack on the Labour right. Not one of his bitter critics was deselected—largely because Corbyn himself had approved measures to block any genuine internal democracy. At the Labour conference in 2018, delegates voted for mild reforms that made it slightly easier for party members to deselect their MP and choose another in their place. But there ought to have been a majority for a far more thoroughgoing change that would require every MP to present themselves to local members for endorsement or removal. It did not pass because Unite voted against it, with the union’s leader Len McCluskey saying he was carrying out Corbyn’s wishes.

Just before the 2019 conference there was an attempt by Momentum founder Jon Lansman to remove the post of deputy leader, held by Corbyn critic Tom Watson. After a backlash from right-wing Labour MPs and union leaders, Corbyn intervened to block Lansman—handing the right a victory. This protection for the right contrasted sharply with Johnson’s purge of his critics. He did not hesitate to remove the whip from 21 Tory MPs—including Kenneth Clarke, Philip Hammond, Nicholas Soames and Rory Stewart—when they voted against him.

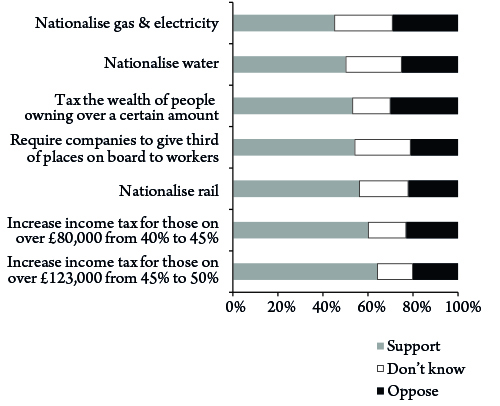

Were the policies unpopular—and were they credible?

The election was not a rejection of left policies of taxing the rich and taking back privatised industries. Poll after poll demonstrated this, for example one by YouGov a few weeks before the election (figure 4).

Figure 4: Support for key Labour policies

Source: YouGov.

A poll of Labour-Tory switchers found an even bigger backing for many of these measures. A majority wanted “to nationalise the railways (67 percent), energy companies (56 percent), and water companies (62 percent). They prefer the idea of more public spending (57 percent) to more tax cuts (17 percent), and more of them think that businesses should pay more tax (38 percent) than less tax (13 percent)”.25 The problem was not that people accepted pro-austerity lies or thought the free market was wonderful. The trouble was that Brexit was allowed to become the central issue, on which Labour ended up on the wrong side to many of its potential voters. Brexit overwhelmed a wider class politics.

It is also true that Labour’s programme of change would have seemed more credible if there had been a much greater sense of class resistance. When people are involved in strikes, protests and demonstrations they gain a sense of collective unity. They are more open to radical ideas. But we have not seen that sort of resistance. Corbyn’s election as Labour leader was a boost to the whole of the left, raising the confidence that socialist ideas can be popular, but the other side of his success was that union leaders, and many activists, staked everything on his electoral advance. There were no big demonstrations, no encouragement for strikes. Even when the Tories hit the rocks, the only response was parliamentary, not on the streets or in the workplace.

Just under a year ago Theresa May’s Brexit deal was rejected by a majority of 230 MPs. It was the biggest ever parliamentary defeat for a governing party. There were never any mass protests, no effort to force the Tories out. Later the parliamentary deadlock forced Johnson to offer a general election on 14 October. Labour ran away, saying it wanted to work with the Liberal Democrats and others to block a no-deal Brexit, rather than go to the polls or take to the streets. Throughout this period many trade union leaders have let down the working class. The failure to push for strikes and the determination to pull everything behind Labour was fatal. It is not automatic that Labour wins elections when there is a high level of struggle, but it is more likely. However, agitating for more struggle should not be posed as a useful electoral move. More struggle is good in itself—welding together working class people across the divides encouraged by our rulers and offering the best hope of working class progress.

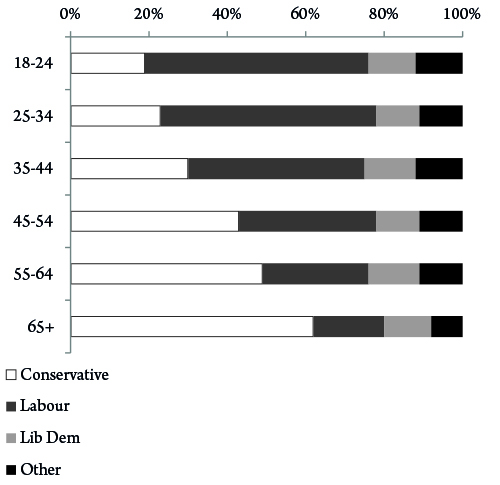

Is age now the big divide?

It has become widely accepted that age, not class, is the defining factor in voting now. The Ashcroft poll found 63 percent of retired people voted Tory, just 18 percent chose Labour. The broader picture is shown in figure 5.26 There is a clear pattern here, similar to one in 2017, but it is far from the whole story.

Figure 5: Party support by age-group

Source: Ashcroft, 2019.

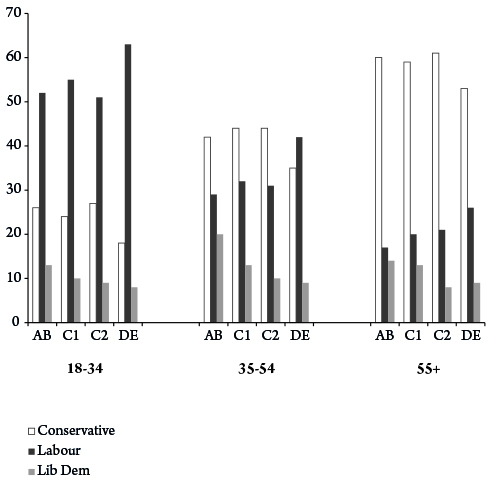

First, there is a class pattern inside the age groups. Roughly, the poorer you are the more likely you are to vote Labour, whatever your age-group (figure 6).

Figure 6: Voting by NRS grade and age-group

Source: Ipsos MORI.

Second, the question of why older people are less inclined to vote Labour is partly rooted in material circumstances. To be clear, I do not mean that all or most pensioners spend their time on luxury trips and defending their wealth from inheritance tax. About 5 percent live in severe poverty, the British state pension is among the worst in the Western world, the social care system is in crisis with 1.8 million people not receiving the help they need and, in the past five years, 170,370 pensioners have died from cold-related illnesses. Nor are all older people crotchety racists singing Vera Lynn or Cliff Richard songs. The ranks of Extinction Rebellion include significant numbers of older people. Older people worry about the planet’s future, their own lives and the future of their children and grandchildren. But it is significant that of those over 65 who vote, 46 percent were previously in the top two categories of “managers, directors or senior officials” or “professional occupations”. For comparison, these categories cover only 35 percent of 45-54 year olds. Over-65 voters make up a third of the AB category, twice as many as in the 45-54 group. On average people get richer as they go through their working life—and the better-off live longer than the poor. In addition four out of five voters over 65 own their own homes.27 This factor matters: someone who rents in their sixties is no more likely to vote Conservative than someone who rents in their thirties.

Moreover, older people are far more likely to vote than younger people. “If we look at the 20 constituencies with the highest proportion of 18-35 year olds, the average turnout was 63 percent. The turnout for the 20 constituencies with the fewest 18-35 year olds was 72 percent”.28 One of the factors behind Labour’s problems in the north of England and the Midlands is how some of those areas have aged on average. Table 2 shows changes from 1918-2011.

Table 2: Changes in age of population, 1918-2011

|

Town |

Change in over 65s population |

Change in 18 to 24 year olds population |

|

Workington |

Up 14.0% |

Down 28.4% |

|

Bury |

Up 27.3% |

Down 7.3% |

|

Southport |

Up 12.4% |

Down 21.8% |

|

Bishop Auckland |

Up 34.8% |

Down 24.9% |

|

Darlington |

Up 21.2% |

Down 16.6% |

|

Hartlepool |

Up 26.9% |

Down 24.5% |

|

Redcar |

Up 8.9% |

Down 24.3% |

|

Grimsby |

Up 39.6% |

Down 19.1% |

|

Scunthorpe |

Up 39.6% |

Down 21.0% |

|

Wakefield |

Up 29.0% |

Down 10.5% |

|

Mansfield |

Up 30.3% |

Down 14.4% |

|

Kirkby-in-Ashby |

Up 41.3% |

Down 15.5% |

|

Bolsover |

Up 35.2% |

Down 16.1% |

However, nothing is inevitable about younger people voting to the left. To take an example from the French presidential election run-off in 2017, some 44 percent of 18 to 24-year-olds backed the fascist Front National’s leader Marie Le Pen, but she was supported by just 20 percent of over 65s.

Something inside so wrong…

The immediate reason for Labour’s defeat was Brexit but this is not the only reason or even, in the longer-term, the most important one. It is crucial to insist on this because there are theories that all that is needed is an anti-EU tweak and Labour will be back on track and delivering for working class people. In reality, Labour has been losing support from significant numbers of workers for decades. In Ernest Hemmingway’s novel The Sun Also Rises one character asks another, “How did you go bankrupt?” The reply is: “Two ways. Gradually, then suddenly.” We might say the same about Labour. Tables 3 and 4 show the social class distribution of Labour’s vote over the past three decades.

Table 3: Breakdown of Labour’s vote by NRS grades, 1992-2010

Source: www.earlhamsociologypages.co.uk/classvotingbehaviourassignment.htm

|

|

1992 |

1997 |

2001 |

2005 |

2010 |

|

AB Labour |

20% |

31% |

30% |

28% |

28% |

|

C1 Labour |

25% |

39% |

38% |

32% |

28% |

|

C2 Labour |

41% |

50% |

49% |

40% |

29% |

|

DE Labour |

50% |

59% |

55% |

48% |

40% |

Table 4: Breakdown of Labour’s vote by NRS grade, 2015-19

Source: YouGov.

|

|

2015 |

2017 |

2019 |

|

AB Labour |

26% |

37% |

30% |

|

C1 Labour |

29% |

40% |

32% |

|

C2 Labour |

32% |

41% |

32% |

|

DE Labour |

41% |

47% |

39% |

It is important to remember that 1997-2007 was the era of Tony Blair, with Gordon Brown taking over from 2007-10. The 2015 election was headed by Ed Miliband. The biggest fall is in the DE category where Labour support slumped from 59 percent in 1997 to 39 percent now. The decline from 1997-2010 is remarkably steady between elections—minus 4 percent, minus 7 percent and minus 8 percent. Only Corbyn’s first election in 2017 reversed the trend, seeing a 6 percentage point increase from 2015. The slump in DE support in 2019 was electorally crucial, but it is simply a return to the levels of 2010 and 2015.

Again, the C2 level of support fell during the Blair and Brown years. This national picture was reflected locally. Between 2005 and 2015, Labour’s vote share fell by 14 percentage points in Bolsover, 12 in Sedgefield, 10 in Don Valley, nine in Bishop Auckland and eight in Rother Valley. As analyst Peter Kellner writes:

In the north east and east midlands, the two regions where Labour’s support has fallen most since 2005, three-quarters of the 8.1 point fall had taken place by 2015 in the north east—and all of the 7.3 point drop in the east midlands, where Labour’s vote share was virtually the same in 2015 and 2019. Labour’s sharp but, in the event, temporary rise in support in 2017 meant that last week’s results generated some huge 2017-19 swings. They obscured Labour’s long-term decline in its heartlands.29

This underlines that Corbyn and his allies should have scrapped the whole Blair legacy. Instead, McDonnell did a chummy interview with Blair’s liar-in-chief Alistair Campbell in GQ magazine, in which he said he would support Campbell’s return to the party. New Labour laid the foundations for 2019. Its veneration of the rich, defence of private firms, lies over Iraq and much else revolted millions. As Aditya Chakrabortty wrote in an article entitled “This Labour Meltdown has been Building for Decades”: “Even as the working class were marginalised politically and destroyed economically, New Labour patronised them into apathy”.30

Working class people saw those who claimed to be their political representatives float off into an alien realm. This created an opening for the rotten politics of Johnson and Farage. In a review of an important book about class, the Marxist author Terry Eagleton wrote in 2017:

The class system, then, has remained remarkably unchanged, and in some ways has become more entrenched. What has changed radically…is class representation at the level of national politics. What began to happen with New Labour’s shift to the right was that the working class no longer had anyone in this arena to champion their interests. It is this, not the dissolution of social class itself, that has altered the political landscape.31

Scotland: Not Brexit, but still a crisis for Labour

The election in Scotland was very different to the one in England. Here it was not principally Brexit that skewered Labour but the legacy of the 2014 referendum. The SNP gained 13 seats, taking it to 48 of Scotland’s 59 MPs. Labour’s vote was down 8 percentage points—to 18.6 percent. The last time Labour secured less than 20 percent was 1910 and even then it won more than the single MP achieved in 2019. This collapse follows the electoral earthquake of 2015 general election where Labour collapsed from 41 seats to one MP. In 2017, under Corbyn there was a slight recovery in seats won, but on the basis of only a 10,000 increase in the Labour vote across the whole of Scotland. Labour’s decision to campaign with the Tories during the 2014 independence referendum remains toxic, cutting them off from a huge swathe of people, particularly the young.

However, again, the roots of the problem go deeper—back to Blair’s time. “The SNP have been the dominant party in Scotland since 2007 and at Westminster since 2015—having won three Scottish Parliament elections and three Westminster elections in a row.”32 Historian Tom Devine has long argued that Labour’s decline in Scotland is a decades-long process:

The transformation in the 1990s of old Labour into New Labour, which seemed to embrace a free market philosophy and failed to reverse Thatcherite reforms, triggered much disenchantment among the party’s supporters in Scotland. Surveys taken after the 1999 Holyrood election concluded that less than half the respondents thought that New Labour looked after Scottish interests. Similar evidence covering the period between 1997 and 2001 demonstrated declining support for the proposition that New Labour looked after class and trade union concerns but increasing agreement with the view that the party primarily looked after the concerns of business and the affluent in society.33

Although Scotland saw a very different election to the one in the rest of Britain Labour’s travails also featured an immediate issue (Scottish independence) and a common long-term one (Blairism).

Going deeper into the defeat

Brexit and Blairism, the lack of struggle and the concessions to the right alone do not capture what happened at the election. There are more fundamental factors. The most important of all is Labourism itself. Whether right-wing or left-wing, Labour governments believe in change within the existing parliamentary system and state structure. Yet, as we know from every previous British Labour government and the recent experience of reformist governments such as Syriza in Greece and the Socialist Party in France, the state and the global financial institutions will not meekly allow fundamental change. The state is geared towards running capitalism and helping big business. Crucially, that means facilitating the exploitation of workers that is at the heart of the system. A vast tangle of laws legitimise capitalists’ right to own property and make profits—while the police, the army and the secret service protect them. State bodies are filled with unelected officials who share broadly the same interests as the bankers who will try to break a left-wing government.

While financial institutions blackmail Labour with investment strikes and market crashes, top civil servants, generals, cops and spies will sabotage the government from inside the state. In the 1970s sections of the bosses and the politicians were terrified by the scale of workers’ struggle in Britain. A leading Tory called Ian Gilmour, then the shadow defence secretary, wrote a book offering his perspective. “Majority rule is a device,” he argued. “Democracy is a means to an end not an end in itself. If it is leading to an end that is undesirable, then there is a theoretical case for ending it.” No such measures proved necessary. But the threat has not gone away. A “senior serving general” told the Sunday Times newspaper that if Corbyn became prime minister, there would be “the very real prospect” of “a mutiny”. Elements in the military would use “whatever means possible, fair or foul,” he said. Corbyn’s cothinkers insisted they knew all this. Hilary Wainwright said in 2018, “Jeremy Corbyn and John McDonnell understand the non-neutral nature of the state.” So the job was to build “the kind of counter-power that will be necessary in the face of the City, the power of the Confederation of British Industry (CBI), the power of the state, the power of media and their allies within the Parliamentary Labour Party and sometimes within the unions”.34

If this was supposed to be the task, it certainly did not happen. Corbyn and McDonnell tried to woo the City and the CBI, not develop a counter-power to them. They compromised with the bosses’ allies in the Parliamentary Labour Party. This was absolutely in tune with a party for which parliament always disciplines extra-parliamentary activity. The retreats over Brexit and antisemitism, the lack of focus on struggle, the support for the British state rather than Scottish independence and the government of Blair can all be presented as individual episodes or mistakes. But, in truth, they are all symptoms of Labourism. In opposition, it means seeking unity with the Labour right to win an election. In government it means trying to placate those forces that will try to destroy it.

Younger people who were attracted to Corbyn had never seen the election of a British Labour government with a left-wing manifesto. For many of them, this argument will have seemed remote, a matter to be dealt with later. Meanwhile, the former revolutionaries and older activists who unconditionally backed Corbyn went through a deliberate forgetting of what they know about capitalism, the state and reformism. But the issue has not gone away and Corbyn was defeated even before the test of office.

The defeat of 2019 was both a result of particular and immediate political choices over Brexit and other issues but also a sharp reassertion of the limitations of reformism itself. In this sense it does indeed hold lessons for the movement around Bernie Sanders or those around Podemos in the Spanish state. Labourism imprisons activists within the iron cage of parliamentary forms. The contest that has been taking place to decide Labour’s next leader has been dominated by one great question—who can help us win an election? The central issue was not that of policy or raising the level of struggle, but who could do best next time around. The Labour right unashamedly adopt such an approach; the Labour left do it more carefully.

The 2015 election loss for Labour led wholly unexpectedly to victory for probably the most left-wing leader the party has ever had. It tested the idea that if only Labour had a proper socialist in charge and a left manifesto then victory would follow—and then major changes in society. The 2017 result gave a further fillip to this idea. However, the 2019 defeat, and the demoralisation for many Labour supporters it has caused, will be used to drive Labour rightwards. The answer is not to hanker after a return to full Corbynism but to focus on the power of resistance by ordinary people outside parliament, in their workplaces and in the streets.

Charlie Kimber is the editor of Socialist Worker and a co-author of The Labour Party: A Marxist History (Bookmarks, 2019).

Notes

1 Norris and Dunleavy, 2020, makes a strong case that the BBC’s framing of the poll and its election night coverage in general helped to popularise the idea of a Tory landslide and that this did not represent reality.

2 Riotta, 2019.

3 Kellner, 2019.

4 Bell, 2019.

5 Gilbert, 2020.

6 There are many class biases behind the facade of equality in bourgeois democracy. Just 58 percent of private renters in Britain have up-to-date register entries, compared with 91 percent of those who own their homes outright.

7 Michell and Jump, 2020.

8 The YouGov survey returns very similar results—YouGov, 2019.

9 YouGov, 2019. Annoyingly, YouGov does not report whether it asked exactly the same questions at the 2017 election about household income, so a direct comparison is not possible.

10 Bell, 2019.

11 The most deprived Scottish constituencies are all held by the SNP. Scottish Government, 2020.

12 There is an argument about how Colne Valley voted in 2016. I have put it in the Leave column, but it does not change the argument if you move it.

13 Curtis, 2020.

14 YouGov, 2019.

15 Ali, 2020.

16 For further details see, for example, Choonara, 2015.

17 Robinson, 2019.

18 Clyne, 2019.

19 For a full analysis of the referendum result see Kimber, 2016.

20 Malik, 2019.

21 Clyne, 2019.

22 Younge, 2019.

23 Reported by Socialist Worker journalist Nick Clark.

24 Sherwood, 2019.

25 Curtis, 2020.

26 Ashcroft, 2019

27 Ashcroft, 2019.

28 Fox, 2019.

29 Kellner, 2019.

30 Chakrabortty, 2019.

31 Eagleton, 2017.

32 Hassan, 2019.

33 Devine, 2016.

34 Clark, 2018.

References