The Occupy movement that began in New York in September 2011 and has spread with remarkable speed across the country represents a massive shift in the politics of the United States.1 A year ago the seemingly inexorable rise of the Tea Party saw the startling resurgence of the right only two years after Obama’s election and the apparently decisive defeat of the Republicans.

In a forthcoming book that has already been partly superseded by events, Thomas Frank launches a stinging attack on the “new right” in the US and makes the point that conservative gains were made thanks to the ideological void left by the Democratic government’s response to the crisis: “The bailouts combined with the recession created a perfect situation for populism in the Jacksonian tradition, for old-fashioned calamity howlers, for Jeremiahs raging against the corrupt and the powerful”.2

We have discussed in this journal the Tea Party’s distorted dissemination of the anger and frustration in US society at the bailouts and the pain of the crisis that made it both a useful tool for big capital to shift the terms of debate rightward (though US capital is nothing like as opposed to government, immigration and so forth as the Tea Party) and an expression of alienation and anxiety among the US middle class. The Tea Party’s self-portrayal as a “grassroots” popular movement provided cover for its politicians, like Wisconsin’s governor Scott Walker, to carry out attacks on working class conditions and social welfare.3

The emergence of a reborn anti-capitalism has seen articulated the same frustration and anger at the gross inequality in US society and government response to the crisis but, rather than representing a middle class howl of protest, the new movement is an independent expression of the bitterness among the vast majority of US society. Its slogans, language and actions have caught the imagination of millions and are influencing workers used to more traditional methods of struggle in a widening ripple effect.

The Occupy movement has its roots in the anti-capitalist movement that emerged in the US at the end of the 1990s. The “Teamster-Turtle” alliance brought together workers and a myriad of activists against the World Trade Organisation at Seattle in 1999 and inspired a worldwide movement against the effects and priorities of capitalism. In the US the movement was effectively broken by 9/11 and the subsequent wars on Iraq and Afghanistan launched by the Bush government. The working class element of the movement—the presence of which at the time represented a significant change in the history of US protest movements—was deflected by Democrat betrayals, right wing Republican rhetoric and deeply conservative and passive union structures. However, the context of severe economic crisis and its devastating affect on US workers—and the rest of the 99 percent—has propelled the re-emergence of widespread protest against capitalism at a higher temperature and has given the Occupy movement an extraordinary energy and momentum, and a depth of reach into the working class, that is creating the conditions for mass resistance. It has itself drawn on the spontaneity and creativity shown during the battle of public sector workers to defend union rights and services in Wisconsin in February and March this year and, in this sense, the twin developments intersect and are conditioning one another in closer combination than has been the case for decades.

The speed of events and the ideological development of the movement means it is possible in this article to make only some general points about the conditions that have led to the shift in class struggle in the US and to point to some of the strengths and limitations of the situation. The central argument here is that the importance of the current moment in the US must not be underestimated.

The self-identification of the movement as the 99 percent of US society who have seen none of the benefits of the increase in wealth over the last 30 years, as opposed to the 1 percent who have been enriched to an enormous degree in the same period, has refocused the bitterness and anger in US society in a clear class direction. The slogan reflects the reality of the deep and growing inequality of wealth, the determination of the richest to make the rest of society bear the burden of the crisis and to use the recession as a political weapon to push through further austerity and attacks on working class conditions, and a developing sense of the role of the state in stifling collective democratic protest and protecting the 1 percent—and a determination, so far, to meet such repression with resistance.

h2 Inequality in the US

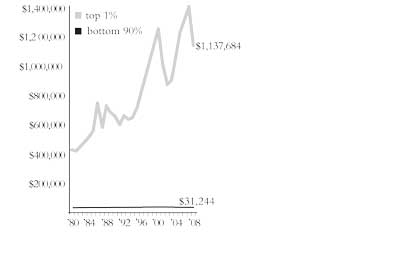

The Occupy movement’s highlighting of the fundamental economic and political inequality in the US has pushed discussion of the disparity of wealth and the enrichment of the ruling class into the national debate—and the ever-accelerating disparity in wealth is breathtaking.

Mark Weisbrot, director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research, in an article whose title, “The Occupy Wall Street Movement: The Real Moral Majority”, neatly encapsulates the transition from the right wing populism of the Tea Party to a genuine grassroots movement grappling with the realities of class, states: “Between 1979 and 2007, the richest 1 percent received three fifths of all the income gains in the country. Most of this went to the richest tenth of that 1 percent, people with an average income of $5.6 million (including capital gains).

This is outrageous”.4

The table below starkly illustrates this. As the Congressional Budget Office makes clear, and as has been discussed before in this journal, the link between increased productivity and increased wages that saw material gains for US workers during the long post-war boom has been broken, and the rate of exploitation forced up over the last three decades.5 Those benefiting from increased capacity in that period have been almost exclusively the top 1 percent in US society. “Average real after-tax household income for the 1 percent of the population with the highest income grew by 275 percent between 1979 and 2007”,6 while “the inflation-adjusted median income for working-age households declined by over $2,000 between 2000 and 2007. This is the only business cycle on record in which the typical working family had less income at the end of a cycle than at the beginning”.7

Figure 1: Average US household income before tax

Source: Congressional Budget Office

In 2008, despite the impact of the recession, the average income of the top 1 percent was still just under $1.2 million while the bottom 90 percent flatlined at $31,000, as the chart below shows.

Indeed, the recession has not had a lasting effect on the wealthiest Americans, who have seen their incomes continue to increase over the last year. In the fourth quarter of 2010 US business profits were up by an astounding 29.2 percent, the fastest growth since the 1950s. As the New York Times reported, the median pay for top executives at 200 major companies was $9.6 million in 2010—a 12 percent increase over 2009:

Many if not most of the corporations run by these executives are doing better than they were in the downturn. Many businesses were hit so hard by the recession that even small improvements in sales and profits look good by comparison. But CEO pay is also on the rise again at companies like Capital One and Goldman Sachs, which survived the economic storm with the help of all those taxpayer-financed bailouts… On this year’s list, the highest-paid CEO was Philippe P Dauman of Viacom, who made $84.5 million in just nine months.8

Figure 2: Average income including capital gains (2008 dollars)

Source: The World Top Incomes database9

As the super-rich have got richer, so the poor have got poorer. A Brookings Institute report based on the population census found that:

[Some] 20.5 million Americans, or 6.7 percent of the US population, make up the poorest poor, defined as those at 50 percent or less of the official poverty level. Those living in deep poverty represent nearly half of the 46.2 million people scraping by below the poverty line. In 2010, the poorest poor meant an income of $5,570 or less for an individual and $11,157 for a family of four. That 6.7 percent share is the highest in the 35 years that the Census Bureau has maintained such records, surpassing previous highs in 2009 and 1993.10

Such extreme poverty is now spreading beyond the industrial midwest where it is the result of the decline in manufacturing to urban “Sun Belt” areas like Las Vegas, Riverside, California, and Cape Coral, Florida, where the biggest growth in deep poverty stems from the destruction of property values and construction jobs in the housing market crash.

Nationally the official unemployment rate remains at around 9 percent, a consistent figure for the last two and a half years, though a broader measure which includes those who are discouraged from looking for work because there are no jobs, or they lack experience or skills or face discrimination, and those who work part-time but want full-time jobs, puts the figure at 16.5 percent: “According to the BLS, 11.4 million Americans do not have an income, do not pay income tax, and do not contribute to producing goods and services. Indeed, almost 15 percent of Americans (45.8 million) are now on food stamps”.11

For those in work, incomes in 2011 were at 1970s levels, while the cost of living—from housing to running a car to childcare to college—has risen markedly. Any lingering consideration that American workers are somehow “bought off” by their acquisition of consumer goods is countered by the material reality of the reduced ability to pay for such items. As the Economist reported in September:

Of course, many of today’s consumer products are of higher quality today than they were in the 1970s, and the typical household has access now to things like iPods and flatscreen televisions that didn’t exist then. On the other hand, the cost of everything from housing to education has risen steadily in recent decades. From a real income perspective, the American economy has already experienced a lost decade, but for the median household the picture is one of a generation of stagnation.12

The stagnation of household income has not been reflected at the top of society, so the share of national income accruing to the majority of Americans today is considerably less than in the 1970s: Between 1979 and 2007 the share of income of the bottom 80 percent of the population fell by between 10 and 30 percent, while that of the top 1 percent increased by 130 percent.

Figure 3: Change in share of after-tax income compared to 1979

Source: Congressional Budget Office

For those Americans with jobs, or students, the fall in real wages, fall in property values, rises in living costs and increasing debt exerts increasingly intolerable pressure on their lives. The moving record on the We Are the 99 Percent blog testifies to the economic strain and the toll it is taking on people’s family, social, working and mental lives.13 The frustration and desperation of the inescapability of economic hardship and political inequality, and their profound impact on the capacity for individual and social development, are common to the students and workers represented there—a commonality and connection that marks a significant change in the relation of these social forces to one another from, for example, the seismic movements of the 1960s.

Put briefly, the US emerged from the Second World War as the world’s largest economy, producing half of the world’s wealth, and US capitalism continued to expand for 25 years. Hourly wages increased 250 percent in the 30 years between 1945 and 1975.14 Workers’ living standards improved dramatically, as US employers were able to contribute to pension funds, insurance and medical benefits. By 1960 some 60 percent of Americans owned their own homes, the production of consumer goods expanded and workers could afford to buy refrigerators, televisions and cars and extend their leisure time. These material conditions meant that the movements against the Vietnam War and for civil rights—though powerful and deeply influential—did not break through to a wider challenge to capitalism, in part because the connections between the upsurge of rank and file anger and the movements were shaped, and weakened, by the conditions of the long boom.15

Four decades later the devastation wreaked on ordinary American lives by neoliberalism and economic crisis has largely collapsed the divisions between workers and wider social protest that existed in the 1960s. The new upsurge in struggle comes from US workers being compelled to confront employers and state governments to resist further degradation in living standards and conditions at a time when the real nature of the system is being exposed not only by their own struggles but by the ideas and language of anti-capitalist activists.

A painful groping towards consciousness

The shift from passive anger to active resistance began in response to the austerity programme of the Tea Party governor Scott Walker in Wisconsin in March 2011. It was collective, organised action by public sector workers in Madison, themselves inspired by the Egyptian Revolution, and articulating what would become the language of the Occupy movement, that first punched a hole in the consensus of recession and exposed the reality behind the threadbare populism of the Tea Party.

This is a tremendously important development in the class struggle in the US, as the reality of class rule and exploitation is revealed by workers’ resistance to the effects of capitalism on their lives—sometimes in piecemeal fashion, sometimes at great speed—beneath the veil of ruling class ideology. As Chris Harman puts it, workers “accept the bourgeois definitions of reality for much of the time. But struggle begins to lift the veil from their eyes. When they begin to struggle, for example, over the length of the working day, they begin to see that it is their exertions that have produced the wealth of existing society. They begin to understand the nature of exploitation and to grasp the underlying character of capitalism”.16

Part of this process has been the result of the dashing of popular expectations of Obama. The president’s lip-service to the “frustration” felt by the Occupy demonstrators cannot erase the fact that his government has consistently sided with those responsible for creating the crisis at the expense of ordinary Americans. Three years of bank and corporate bailouts, the defence of bonuses for executives at JP Morgan Chase and Goldman Sachs who were part of creating the sub-prime mortgage market, and inadequate and piecemeal stimulus measures have enraged millions. In November 2011 60 percent of voters said they disapproved of Obama’s handling of the economy, the highest on record, and his overall approval ratings were just 43 percent.

Kalle Lasn of Adbusters, the magazine that put out the call for the Occupy Wall Street demonstration, interviewed about why no action was called with the collapse of Lehmann Brothers in 2008 and the onset of the recession, expresses those hopes and the fallout when they were betrayed:

When the financial meltdown happened, there was a feeling that, “Wow, things are going to change. Obama is going to pass all kinds of laws, and we are going to have a different kind of banking system, and we are going to take these financial fraudsters and bring them to justice.” There was a feeling like, “Hey, we just elected a guy who may actually do this.” In a way, there wasn’t this desperate edge. Among the young people there was a very positive feeling. And then slowly this feeling that he’s a bit of a gutless wonder slowly crept in, and now we’re despondent again.17

That despondency meant that the movement—especially among young people—that got Obama elected was disillusioned by the time of the mid-term elections in November 2010, and Obama’s inability to deliver a different kind of system gave ground to the Republican and Tea Party right. The twin evils of a Democratic administration blatantly siding with the banks and the wealthy and Tea Party politicians forcing through austerity measures led to a growing sense of self-activity as the only option to resist the effects of the crisis by some workers and activists—a sense that is steadily gaining adherents. As Mark Weisbrot says:

It was a mass movement that elected President Obama, with record numbers of small contributors and volunteers. But we did not get the “change we can believe in”. The OWS [Occupy Wall Street] groundswell is the movement of the disenfranchised, the more than 99 percent who do not give the maximum political contribution to our corrupt political system and therefore have little or no voice. They are America’s conscience, and its greatest hope at this time.18

Rage against the bank bail-outs that the Republicans and the Tea Party directed at the “intellectual” ruling class in government to push a free-market, anti big government agenda now centres on the institutions of class power in the US that encompass Wall Street and Washington and the nexus of links between the two and, crucially, poses redistributive alternatives: calls for a tax on financial transactions, for public works, and opposition to union-busting and cuts in education and services stem from a rejection of the priorities of the free market and the devastation they cause, and represent a qualitative leap forward in mass consciousness in the US.

Connecting struggles

It is of central importance that this time around it was organised working class activity that shifted the balance in US politics. The mass protests in Wisconsin that erupted in February and escalated to several 100,000-strong rallies and the occupation of the state government building for several weeks, turning it into a collectively organised space with constant meetings and debates, launched a tremendous show of solidarity and strength against proposed cuts and attacks on union rights by Tea Party governor Scott Walker. Although the Madison uprising was defeated and the austerity bill passed, it put mass working class action firmly on the agenda in a way not seen in decades. The creativity, spontaneity and organising power seen over those months in Wisconsin began to pose an alternative pole of attraction to the populist right in US society.

The Occupy movement has sprung from the same ground, and the new movement has in turn struck a chord with ever-widening sections of the working class and is feeding into an increased confidence and combativity among US workers. Demands of the 99 percent are appearing on union websites and on placards. An AFL-CIO memo sent out at the end of October recommended that unions use the Occupy message about inequality and the 99 percent in their dealings with members, employers and voters. “The Occupy movement has changed unions,” Stuart Appelbaum, the president of the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union, told the New York Times. “You’re seeing a lot more unions wanting to be aggressive in their messaging and their activity. You’ll see more unions on the street, wanting to tap into the energy of Occupy Wall Street”.19

And new-found confidence and fresh methods of protest have delivered concrete victories. In November in Ohio unions and Occupy Cincinnati activists succeeded in overturning an anti-union Senate Bill and inflicted a major defeat on Republican governor John Kasich, who personally led the campaign to limit collective bargaining and the right to strike of public sector employees. An Occupy activist involved in the campaign to overturn Kasich’s bill explained how it had won:

The We Are Ohio coalition spent $30 million, including big investments from national unions. The National Education Association alone gave $10 million, while teachers’ unions in Ohio levied additional dues to help pay for the campaign. Rank and file members knocking on doors and talking on the phone won this one. Thousands of members from AFSCME [American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees], teachers’ unions, firefighters, and many other public and private sector unions put in untold hours.20

In Oakland on 2 November demonstrations closed the port down and won solidarity from dock and other workers. A planned shutdown of all West Coast ports by Occupy activists and workers in solidarity with the longshoremen’s dispute with EGT (an international grain export company) and the Teamsters’ with Goldman Sachs was due to go ahead on 12 December as this journal went to press. The aims of the blockade combine defence of workers with resistance to state repression of the Occupy movement, as the statement issued by the West Coast Port Blockade Assembly of Occupy Oakland made clear:

We’re shutting down these ports because of the union busting and attacks on the working class by the 1 percent: the firing of port truckers organising at SSA terminals in Los Angeles; the attempt to rupture ILWU [longshoremen] union jurisdiction in Longview, Washington, by EGT. EGT includes Bunge Ltd, a company which reported 2.5 billion dollars in profit last year and has economically devastated poor people in Argentina and Brazil. SSA is responsible for inhumane working conditions and gross exploitation of port truckers and is owned by Goldman Sachs. EGT and Goldman Sachs is Wallstreet on the Waterfront. We are also striking back against the nationally coordinated attack on the Occupy movement. In response to the police violence and camp evictions against the Occupy movement—this is our coordinated response against the 1 percent.21

In New York on 1 December some 20,000 people took part in a demonstration organised by the New York Labor Council, which called on anyone “who is frustrated and worried about the growing economic disparity in this country” to take to the streets and demand accountability from their elected officials. The involvement of workers, including teachers and electricity workers, was greater than in November. As if to demonstrate the disparity, the previous week in New York a fundraiser for Obama’s re-election campaign was held at $35,000 per ticket—a figure higher than the average American’s yearly income.

Unions in California, New York and elsewhere have been at the forefront of supporting the Occupy movement practically, providing showers, food and medical assistance to protesters. Such combined action and reciprocal support between anti-capitalism and the organised sections of the working class represent a real breakthrough and pose exciting possibilities, but to emphasise the positive developments in the US is not to underestimate the real difficulties the movement will need to overcome. The long-term decline in union membership is one such factor: unionisation now stands at 11.9 percent, down from 12.3 percent last year. During the last decade there were only 17 strikes, compared to 269 between 1970 and 1981. There were only 11 stoppages—which encompass strikes and lockouts—involving more than 1,000 workers in 2010. That is the second lowest on record after 2009, when stoppages hit a record low of five, the fewest since the department began tracking labour conflicts in 1947.22 Strike figures for 2011 so far appear to be higher, but it remains to be seen whether the movements of this year will translate into more significant organised challenges to the employers.

In addition, US union leaders have a long history of conservatism and passivity, and in some cases are not far from being part of the 1 percent themselves. As reported in Labor Notes, the number of union officials earning over $100,000 a year “tripled between 2000 and 2008, the latest year with complete data, and the number earning more than $150,000 also tripled… Officials earning more than $150,000 found themselves among the richest 5 percent of American households. Meanwhile, the typical union member earned $48,000 in 2008; the overall average US income was $40,000”.23

In many cases union leaderships are resistant to the emergent and spontaneous democracy of the Occupy activists. For example, although many individual ILWU members are supportive of the proposed West Coast shutdown, the ILWU’s official position is that its own democratic processes have to be followed before it can join the protest.

The overall unionisation rates also disguise the fact that in the south and the west unionisation is virtually non-existent, and the recession has made it easier for employers to replace entire workforces if they strike. Millions in call centres, hospitals, the meatpacking industry and the Walmart retail empire are not unionised, and the labour leaderships have consistently failed to commit to a campaign of recruitment and recognition in these areas. Significantly, however, the Occupy movement is drawing attention to the plight of non-union workers with a dynamism and outrage long missing from official union pronouncements, as this Occupy Denver statement shows:

We call on every occupation to organise a mass mobilisation to shut down its local Walmart distribution centre. Our eyes are on their continued union-busting and attacks on organised labour, their unfair trade practices, the slave labour products that are defiling the world. These horrors are being forced on our communities through a coordinated effort between the 1 percent and the government of the United States through corporate kickbacks, tax credits, and a pattern of unaddressed and unenforced workers’ rights claims. Walmart is a business that has commoditised and enslaved our entire world for the benefit and profit of a very few.24

Another concern for the movement is the mistrust on the part of some Occupy activists about the involvement of the unions. This in part reflects a desire for autonomy and a mistrust of unions as institutions but also reflects sensible concerns that union leaderships, and groups like MoveOn.org, are attempting to co-opt the movement and channel it into the Democratic election campaign. As one protester in Washington DC put it: “MoveOn’s been working very hard. They’d love to turn [the Occupy movement] into a pet until the election and then have it neutered. They don’t have the momentum or public support we have.” Another drew parallels with the Tea Party movement: “The Tea Party is exactly what we want to avoid. We’re not going to be led into the Democratic Party”.25

The history of the co-option of social movements in the US into the Democratic Party—from civil rights to the anti-war movement—makes this a genuine danger, but the movement’s ability to resist such pulls and to strengthen its independence will in large part depend on its ability to forge deeper and broader links with rank and file workers, and for those workers to draw on the movement’s imagination and verve to begin the process of regenerating their unions at the bottom to counter the conservative influence and weight of their leaderships.

A more immediate question for the occupations is police repression and the destruction of the camps. The pictures of a college policeman at University of California Davis pepper-spraying students in the face at point blank range is perhaps the most viewed image of police brutality against the occupations, but it is part of a state campaign of repression against the movement, and one that Obama has refused to condemn. At the time of writing the response from the occupiers has been one of defiance, and it appears that the repression has backfired—some 10,000 students rallied at UC Davis demanding the disbanding of the college police force and nowhere has the police action succeeded in derailing the protesters. In fact, the opposite is true. As Glen Greenwald wrote recently:

Acts of defiance, courage and conscience are contagious… For the first time in a long time, the use of force and other forms of state intimidation are not achieving their intended outcome of deterring meaningful (ie, unsanctioned and unwanted) citizen activism, but are, instead, spurring it even more. The state reactions to these protests are both highlighting pervasive abuses of power and generating the antidote: citizen resolve to no longer accept and tolerate it.26

Nonetheless, the ability of the movement to continue to resist state repression as the stakes rise will also depend on its connection and support among wider sections of organised workers that can spread political resistance to workplaces as well as on the streets in defence of the grassroots democracy that is causing increasing anxiety for college administrations and state governments.

Whatever the limitations and problems built into the current situation, however, the movement has the potential to unite the creativity and initiative of the protesters with the day to day struggles—and the power—of the working class, to place the organised working class at the heart of a movement that poses an alternative to the system as a whole and, in the process, to forge a new left wing politics. As such it is, without doubt, the most important political development in the US for many years.

Notes

11: One indication that US politics has shifted dramatically during the last 12 months since the mid-term elections is the candidature of the 99 percent for Time magazine’s “Person of the Year” – ultimately won by “The Protester” – www.time.com/time/person-of-the-year/2011/

2: Frank, 2012, p167.

3: See Trudell, 2011.

4: Weisbrot, 2011.

5: Trudell, 2010.

6: Congressional Budget Office, 2011.

7: Mishel and Shierholz, 2010.

8: Costello, 2011.

9: Chart composed using data from the World Top Incomes database for Mother Jones website. See http://motherjones.com/mojo/2011/10/one-percent-income-inequality-OWS

10: Guardian website data blog, 3 November 2011: www.guardian.co.uk/news/datablog/2011/nov/03/us-poverty-poorest

11: Guardian website economics blog, 4 November 2011: www.guardian.co.uk/business/economics-blog/2011/nov/04/true-picture-us-unemployment

12: Economist website blog, 14 September 2011: www.economist.com/blogs/dailychart/2011/09/us-household-income

13: wearethe99percent.tumblr.com

14: Le Blanc, 1999, p108.

15: For reasons of space this is a compressed discussion of the period. For more see Harman, 1988, and Le Blanc, 1999.

16: Harman, 1983.

17: Eifling, 2011.

18: Weisbrot, 2011.

19: Greenhouse, 2011.

20: La Botz, 2011.

21: West Coast Port Blockade press statement: http://westcoastportshutdown.org/content/press-release-support-grows-west-coast-port-shut-down

22: Yoshikane, 2011.

23: Smith, 2011.

24: Occupy Denver Walmart Port Shutdown Action: http://westcoastportshutdown.org/content/1212-occupy-denver-walmart-port-shutdown-action

25: Whelan, 2011.

26: Greenwald, 2011.

References

Congressional Budget Office, 2011, “Trends in the Distribution of Household Income Between 1979 and 2007” (October), http://cbo.gov/ftpdocs/124xx/doc12485/10-25-HouseholdIncome.pdf

Costello, Daniel, 2011, “The Drought Is Over (at Least for CEOs)”, New York Times (9 April), www.nytimes.com/2011/04/10/business/10comp.html

Mishel, Lawrence, and Heidi Shierholz, 2010, “Recession Hits Workers’ Paychecks”, Economic Policy Institute Briefing Paper 277 (August), www.epi.org/page/-/pdf/bp277.pdf

Eifling, Sam, 2011, “The Magazine Editor Who Launched the Occupy Movement on ‘Soft Regime Change’ in America”, Minyanville website (3 November), www.minyanville.com/businessmarkets/articles/kalle-lasn-adbusters-kalle-lasn-occupy/11/3/2011/id/37709

Frank, Thomas, 2012, Pity the Billionaire: The Hard Times Swindle and the Unlikely Comeback of the Right (Random House).

Greenhouse, Steven, 2011, “Occupy Movement Inspires Unions to Embrace Bold Tactics”, New York Times (8 November), www.nytimes.com/2011/11/09/business/occupy-movement-inspires-unions-to-embrace-bold-tactics.html

Greenwald, Glenn, “The Roots of the UC-Davis Pepper-Spraying”, Salon.com

(20 November), www.salon.com/2011/11/20/the_roots_of_the_uc_davis_pepper_spraying/

Harman, Chris, 1983, “Philosophy and Revolution”, International Socialism 21 (autumn),

www.marxists.org/archive/harman/1983/xx/phil-rev.html

Harman, Chris, 1988, The Fire Last Time: 1968 and After (Bookmarks).

La Botz, Dan, 2011, “Can Ohio Unions’ Rebuke To Republicans Be Sustained?”, Labor Notes (22 November), http://labornotes.org/2011/11/can-ohio-unions-rebuke-republicans-be-sustained

Le Blanc, Paul, 1999, A Short History of the US Working Class (Humanity).

Smith, Sharon, 2011, “The Future in the Present: Marxism, Unions and the Class Struggle”, International Socialist Review 178 (July-August).

Trudell, Megan, 2010, “From a Bang to a Whimper: Obama’s First Year”, International Socialism 125 (winter), www.isj.org.uk/?id=608

Trudell, Megan, 2011, “Mad as Hatters? The Tea Party Movement in the US”, International Socialism 129 (winter), www.isj.org.uk/?id=698

Weisbrot, Mark, 2011, “The Occupy Wall Street Movement: The Real Moral Majority”, CEPR website (1 December), www.cepr.net/index.php/op-eds-&-columns/op-eds-&-columns/protesters-reflect-vast-majority-on-99-percent-of-most-major-issues

Whelan, Aubrey, 2011, “Occupy DC wary of being hijacked by unions, Democratic activists”, Washington Examiner (1 December), http://washingtonexaminer.com/local/dc/2011/12/occupy-dc-wary-being-hijacked-unions-democratic-activists/1967056

Yoshikane, Akito, 2011, “Quiet on the Labor Front: 2010 Strikes and Lockouts Were Second Lowest on Record”, In These Times (9 February), www.inthesetimes.com/working/entry/6925/2010_strikes_and_lockouts_were_second_lowest_on_record/