Lazy clichés run through the liberal media’s depiction of the so-called “ungovernability of France, popular resistance to the advance of neoliberalism that seems so inexorable elsewhere” and the country’s “rigid labour market and work rules that supposedly stand in the way of economic progress”.1 Far from being restricted to the Anglo-Saxon press, this tune of “unreformable, archaic France” regularly tops the charts in France itself, from Jacques Chirac to Nicolas Sarkozy, François Hollande and Emmanuel Macron, not to mention the mouthpieces of MEDEF, the powerful bosses’ syndicate, and virtually all of the mainstream media. Needless to say, since the sudden irruption of the Gilets Jaunes (or Yellow Vest) movement on a scene already disturbed by the high-profile strikes and demonstrations of the past few years, such talk has intensified further, leaving one wondering how on Earth a capitalist country so impervious to the laws of modern political economy has managed to see its gross domestic product quintuple since the mid-1980s. Unfortunately, there is no French miracle, and, as Chris Howell reminds us, any serious assessment of the French scene should conclude that “all aspects of the French economy have experienced far-ranging liberalisation, through privatisation, supply-side macroeconomic policy and deregulation of financial and labour markets. The result has been growing inequality, dualism and insecurity”.2

French capital and labour in the neoliberal era

How and to what extent the French economy has liberalised is perhaps what distinguishes France from the textbook “neoliberalisation” scenarios of the violent, systematic union-busting professed and successfully applied by Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan. Unlike in Britain and the United States, French voters elected a left-wing president, François Mitterrand, in the early 1980s. Mitterrand and his Communist Party allies sought to save capitalism from itself, by responding to the crisis with an overall wage hike, stimulating consumption and manufacturing. When the capitalist class, through investment strikes, capital flight and attacks on the national currency, expressed its reluctance to be saved, Mitterrand announced the “tournant de la rigueur”—turn to austerity—in March 1983, meaning the beginning of neoliberal, pro-market reforms.

Thus the French version of what Tariq Ali likes to call the “extreme neoliberal centre” was born, not in a Thatcherite crucible of open confrontation with the working class, but through a tranquil betrayal by a left eager to accommodate to capital. Politically, the neoliberal consensus between left and right was gradually built in the 1980s and 1990s through successive so-called cohabitations between president and prime minister of opposing political affiliations, when the vagaries of the electoral calendar would return right-wing parliamentary majorities under a left-wing president and vice-versa. Privatisation, for instance, has progressed with little apparent regard to the political identity of presidents and prime ministers (see table 1).

Table 1: Rounds of privatisation under right-wing and left-wing governments, 1986-2005

Source: Poingt, 2018.

|

Period |

President |

Prime minister |

Value of privatised state assets |

|

1986-8 |

François Mitterand (left) |

Jacques Chirac (right) |

13 |

|

1993-5 |

François Mitterand (left) |

Édouard Balladur (right) |

26 |

|

1995-7 |

Jacques Chirac (right) |

Alain Juppé (right) |

|

|

1997-2002 |

Jacques Chirac (right) |

Lionel Jospin (left) |

30 |

|

2002-5 |

Jacques Chirac (right) |

Jean-Pierre Raffarin then Dominique de Villepin (right) |

13 |

Privatisation as pursued by successive governments must be seen as a move away from the “dirigiste” policies of state ownership that had presided over the destinies of French capital during the long boom—a 30-year period in which France was, incidentally, ruled by right of centre governments. Contrary to what is implied in David Harvey’s fashionable formula of “accumulation by dispossession”, privatisation does not necessarily open up new sectors for capitalist accumulation. In the case of France, companies that were privatised or part-privatised included building materials manufacturer Saint-Gobain, oil giant Elf Aquitaine, Renault, France Télécom and Air France, already dedicated to competitive capitalist accumulation under state ownership.

To put privatisation in the context of the long trajectory of capital and its imperative of wage suppression, we may take up Ben Fine’s suggestion that “privatisation has been an important way in which the relation between labour and capital has been reorganised”.3 The fates of Orange (previously France Télécom) and La Poste are particularly instructive in this regard. In both cases, the change in status from public service to state-owned business enterprise and finally to joint-stock company has allowed the introduction of ruthless policies of wage suppression.4 This has resulted in catastrophic increases in cases of nervous exhaustion, depression and other mental health issues among workers, driving many of them to suicide.5 Sectors as diverse as Renault and public healthcare also saw spikes in suicides in recent years, reflecting a secular increase in mental health risks at work against the backdrop of sped-up working rhythms, as bosses in both the private and public sectors ask workers to “do more with less”.6

Privatisation and austerity in public services deal the working class a double blow: not only do they degrade conditions inside the workplace, but they also degrade quality of life for the working class and the poor, who were the first to benefit from those services. To name but a few examples, two thirds of maternity wards in France have disappeared since 1989, as has 7 percent of public hospitals in the 2013-17 period, while a third of post offices have closed since 2005. Public care homes, already cut to the bone over the past 20 years, faced renewed cuts in 2017, leaving even Macronist MPs embarrassed by the “undignified” conditions they witnessed. Finally, an OECD report indicated that France’s public education system did little to remedy social inequalities.7 The population of rural areas and black working class suburbs (the banlieues) are among those disproportionately affected by the calamities of French neoliberalism. As Mathieu Rigouste argues: “The segregation of the new ‘wretched of the city’ in the suburbs turned them into the experimental fields of neoliberalism, consisting of cutting social funding while reducing the State to its security apparatuses”.8

Naturally, racism and Islamophobia were invoked to cover the failings of French capitalism, and a whole discourse around so-called “sensitive neighbourhoods” and problems of integration emerged to justify both the crimes of the police and the economic marginalisation of the descendants of immigrants. In a way, as many have repeated, the poverty and economic insecurity that gave birth to the Gilets Jaunes movement had been haunting the banlieues since the 1980s.

Precariousness in employment has also progressed: subcontracting, fixed-term contracts, temporary work agencies and other derogations in both the private and the public sector have allowed employers to bypass the most favourable collective bargaining agreements, while sapping solidarity between unionised workers on open-ended contracts and the rest.9 Over the past 15 years, the proportion of fixed-term contracts has slightly gone up from 10 to 12 percent of all waged workers; however, the average length of a contract has more than halved, from 112 to 46 days.10 A relatively small minority of workers is therefore working under shortening fixed-term contracts: the precarious are more and more precarious. Unsurprisingly, women and younger workers are overrepresented in this category.

So the wider French working class has not been spared from privatisation and austerity, but the ruling class remains far from satisfied with its neoliberal reforms: many opportunities to drive a Thatcherite dagger through the heart of the organised working class were missed down the road—notably in 1995, when the newly elected right-winger, Jacques Chirac, was compelled to back down from a generalised attack on pensions by the largest national strike since 1968. This defeat defined Chirac’s presidency, and he became somewhat of a Brezhnevian symbol of stagnation in the eyes of the bourgeoisie by the end of his “mandate for nothing” in 2007.

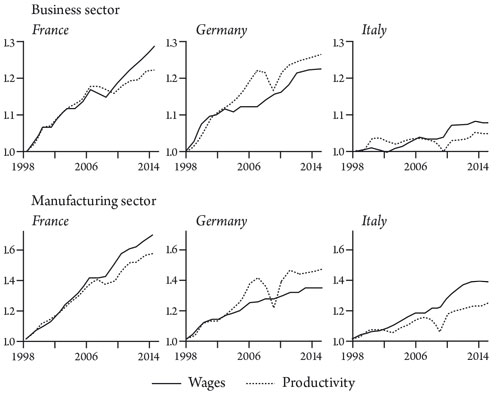

The years leading to the economic crisis of 2008 saw a slight increase in wages in France, while the French bosses’ German, Italian and British rivals, to name a few, have been able to squeeze their workers’ wages.11 Studies suggest that this tendency has actually accelerated since the crisis, with wages increasing faster than productivity in both manufacturing and the overall business sector, in spite of a stubbornly high unemployment rate. Again, this is compared to German wages, which have lagged behind productivity over the same period of time (figure 1).

Figure 1: Evolution of wages and productivity in France, Germany and Italy, 1998-2014

Source: Berger and Wolff, 2017. All variables indexed to 1998 levels.

One explanation for persistently high wages in France may be that in this advanced capitalist economy, bosses need to retain certain skilled workers, limiting their recourse to fixed-term or temporary work contracts. A recent upsurge in manufacturing demand also revealed an unexpected problem: the 2.6 million strong “reserve army of labour” proved incapable of remedying acute shortages of skilled workers.12

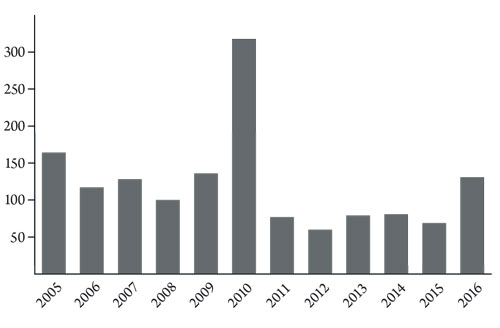

High levels of strike action also contributed an upwards pressure on wages. According to data put together by the Wirtschafts und Sozial-wissenschaftliches Institut (Institute of Economic and Social Research),13 France’s business sector remains the European champion of work stoppages with 132 strike days per 1,000 workers per year between 2005 and 2014, more than five times the British average over the same period. Strikes in the non-business public sector, including education and healthcare, are even more frequent, reaching 329 days per 1,000 workers in 2011.14

A more detailed review of the 2005-16 period (figure 2) reveals the fluctuations of labour struggle in the business sector. The high averages of 2005-9 are the norm under right-wing governments (Chirac then Sarkozy from 2007) and culminated with the national movement against Sarkozy’s pension reform in 2010; subsequent years under a supposedly left-wing government saw a notable dampening of struggle, but 2016 raised the bar again with the mobilisation against the new labour law, or El Khomri law. Looking at the years 2015 and 2016, it is interesting to notice that strikes in the business sector were concentrated in manufacturing and transport. Unlike 2016, which was dominated by a major national strike movement against the El Khomri law, 2015 saw mainly local or sectoral disputes, largely within the same pool of companies that mobilised nationally a year later. Unsurprisingly, those are the largest companies that concentrate both workers and trade union activists together in one place.15

Figure 2: Number of strike days per 1,000 workers per year, business sector

Source: Dares Résultats, 2018.

The most obvious paradox of French trade unionism is that its level of achievement is in spite of a very low aggregate density. Not more than 11 percent of French workers are members of a trade union, yet over nine tenths of them are covered by a collective bargaining agreement.16 This is another explanation for persistently high wages across the board, since pay and conditions resulting from national or sectoral agreements apply as a minimum to all companies, regardless of local union strength. Trade unions therefore perceive little immediate incentive for mass recruitment drives, as they are still capable of mobilising workers without recruiting them as members; the correlation between the presence of union activists on a site and the likelihood of strikes remains solid.17

In the light of this reality of stubbornly high wages, the strategy adopted by the French ruling class since Hollande becomes clear: after decades of temporary fixes, a radicalised ruling class seeks decisively to shift the balance of power towards the bosses.

Hollande: the crisis accelerates

After a largely oratorical flirtation with anti-austerity, in 2014 Hollande announced a sharp turn to the right by promoting interior minister Manuel Valls to prime minister.

Valls never hid his affinities with MEDEF, and its idée fixe of reducing the “cost of labour” at any price. He kicked off a vast programme of state subsidies for companies, and MEDEF chief Pierre Gattaz embarked on a media tour to promise the creation of “one million jobs” in return for the subsidies programme, which reached a yearly total of 172 billion euros in 2017 according to the CGT union confederation.18 A report mandated by the PM’s office found that the money “went primarily into restoring the business sector’s profit margins and to a lesser extent towards wage increases, without favouring mass job creations. No notable effect on investment has been observed”.19

After the November 2015 terrorist attacks, Hollande sought to unite the country behind the ruling class through nationalist rhetoric, notably organising a giant “republican march against terrorism”. As Ugo Palheta has argued: “It has become clear that the government has exploited the terrorist attacks to impose an authoritarian agenda around which the principal French political parties converge”.20

It was in this context, when it appeared as if a police state had suddenly descended upon society and filled the air with a deafening chauvinistic and Islamophobic racket, that Hollande launched his frontal attack against the working class with the “El Khomri” labour law. From the point of view of the ruling class and the state, the timing of the attack could not have been better, for “the eruption of the movement against the El Khomri law actually surprised union activists in the political context of the rise of the Front National and the security measures which had been reinforced following the 2015 terrorist attacks”.21

The fight against the labour law lasted several months and saw several different sectors of society throw themselves into struggle. Some strikes and demonstrations built from below fed into a high school and university movement. At the same time, the occupation of squares began in March 2016 with the Nuit Debout (“night on our feet”) movement before the heavyweight trade union federations began strikes in strategic sectors. All converged in massive demonstrations “against the labour law and its world” in the face of savage police repression. This in turn fed into a new phenomenon, the “head contingents” with hundreds of members of the radical left going ahead of the official demonstrations in a bid to confront the police directly.

Strikes among cleaners, whose working conditions are already worse than anything outlined in the El Khomri law, have continued to flash up, with small but high profile and victorious actions in hotels, hospitals and train stations, a significant development for this notoriously under-organised sector, with a largely black, female workforce.

However, the movement as a whole did not reach the critical mass needed to force the government to yield. In addition to the extraordinary police and judicial repression unleashed against striking workers, picket lines and demonstrations, militant trade unionists ultimately failed to mobilise sufficiently at company level. The sequence of events of 2016 shows that, although the slogan of the “general strike”, and behind it the recognition of the objective power of the working class, remain central even to “new” types of mobilisations like Nuit Debout, the translation of this slogan into reality cannot rely on national trade union leaderships.

But the rulers’ victory in the battle for the labour law came at a great political price. The imposition of the harshest neoliberal reforms turned into a kamikaze operation in which Hollande sacrificed not only what remained of his own popularity, but the Socialist Party itself, which definitively collapsed after a last stab in the back of the working class and the poor. This opened the door for Macron.

The rise of Macron

An up-and-coming former civil servant, economy minister Macron succeeded in building a solid reputation among the French ruling class, from the employers’ federation to politicians and high-ranking civil servants, quickly becoming a media favourite. He surrounded himself with communication advisors, founding the “La République En Marche!” (LREM) movement with the sole aim of marketing the “Macron candidate” brand. Shrewdly, he left the sinking Hollande-Valls ship on time and announced his candidacy as what remained of both the president and his prime minister’s electoral credentials melted into air.

At the same time, members of the conservative “Les Républicains” (or LR, a rebranding of the UMP, Chirac’s and Sarkozy’s presidential vehicle) overwhelmingly and unexpectedly chose François Fillon, Sarkozy’s former PM, to represent their formation in the 2017 elections. Ideologically, Fillon represents the reactionary, pro-Catholic, anti-Muslim and anti-gay provincial French bourgeoisie. His open Islamophobia, homophobia and nostalgia for the French colonial empire hid a no less significant radicalisation: in a speech given before a charmed employers’ federation, François Fillon promised a “blitzkrieg”22 of violent neoliberal measures that would radically transform the French economy in a matter of months.

The designation of Fillon as the candidate for Les Républicains was only another indicator of the strategic, inescapable right-wing turn taken by the French state as a whole. But Fillon’s campaign unravelled spectacularly when it was revealed that this moralising Catholic had paid his wife nearly a million euros in public money for a job she evidently did not do. Battered on all sides by the media and his own party’s cadres who demanded his withdrawal, Fillon hung on desperately and fell back on his reactionary supporters to weather the storm, steering his campaign further rightwards and accelerating the defection of voters towards the new media favourite, Macron. This left the former prime minister unable to cross the first round threshold in spite of an impressive—all things considered—score of 20 percent.

If Fillon’s campaign appealed to the hardened provincial reactionaries, Macron sought to flatter their polar opposites on the bourgeois spectrum: young, urban, well-to-do executives who hide their intellectual indigence behind deluded, LinkedIn-savvy talk of “disrupting” the French political field and turning their country into a “start-up nation”. Macron played the comedian and attuned all his discourse to this pitch; the pathetic punchlines in his bizarre speeches were welcomed with constant, and, as has been revealed, scripted applause.23

Macron’s meteoric rise dazzled the mainstream media, who started zealously to look for the secret to the young man’s success in his own persona. It would be difficult, however, to conceive of a figure who passively embodies the French political disarray as well as Macron; he did not “make history” but is the product of impersonal historical forces in which he played only a supporting role.

Indeed, the Socialist Party’s self-immolation on the altar of capital, the crisis of the mainstream right—of which the Fillon scandal was only a catalyst—and the rise of Marine Le Pen, which frightened enough left voters into turning towards the media favourite, and finally the record abstention rate, all those symptoms of the organic crisis of the French ruling class poured into the swamp of the “candidate Macron”. This is how a cunning opportunist was carried to the head of a major imperialist state to the stormy applause of starry-eyed halfwits.

Upon his election, Macron quickly exchanged his start-up sales manager costume for that, more solemn but no less pathetic, of the head of the French Republic. The executive army of the state replaced what remained of the naïve LREM activists.

Macron stayed on Hollande’s course full steam: on the one hand, he reinforced the state’s repressive apparatus, particularly against migrants and refugees, and on the other, he pursued a series of pro-capitalist fiscal and labour reforms. He set out to attack a bastion of the working class by announcing the coming privatisation of the railway company SNCF and the end of the railway workers’ hard-won terms and conditions. Even if the railway strike, which lasted three months, did not hit the government hard enough to make it blink, it produced a reaction similar to the struggle against the El-Khomri law: a great national strike occupying the front pages of the newspapers, a fierce high school and university student struggle and rising migrant and anti-racist movements, organising and converging on the streets in the face of an escalating police repression. All showed an ongoing accumulation of left-wing radicalism that was not stifled by the defeats of the labour movement of the past few years.

However, society will not simply tip to the left until power falls on our laps. The leftwards radicalisation is counterbalanced by a polarisation to the far right, most notably around the National Front (rebranded last year as Rassemblement National) and the 11 million votes it gathered at the 2017 presidential elections.

The far-right: republican racism nurturing a fascist core

In the midst of the long economic and political crisis, it has appeared to many commentators as if the principal French fascist party, the Front National, had succeeded in shaking off its fascist remains to become a “republican” party, republicanism being understood here as a French idiom for democratically legitimate. This analysis has justified an end to the effective boycott of the FN by nearly all mainstream bourgeois parties: Macron agreed to hold a televised confrontation with Marine Le Pen before the second round of the presidential election, while Chirac, hardly an anti-fascist activist, had refused to hold a similar debate with Marine’s father Jean-Marie, the Front’s candidate in 2002.

Like all political organisations, fascist parties are living organisms that are subject to evolution as they react and adapt to the concrete political situation they find themselves in, particularly when the possibility of a direct bid for power is excluded from the short-term agenda. The Front National, which was founded in the early 1970s as an attempt to unite small Nazi organisations and—already at the time—endow them with a mainstream electoral legitimacy, is certainly no exception to this rule. It has gone through multiple crises and transformation, but without estranging itself from its fascist nature.

This is not the place to go through a detailed history of the Front National and French fascism, but let us describe it in its current state, under Marine Le Pen, as a far-right electoral organisation around a fascist core. Over the past decade, Le Pen has sought to widen the influence and the electoral appeal of the FN by adopting a renewed racist discourse that puts Islamophobia, rather than antisemitism, at the forefront. That such a move has “detoxified” the FN and endowed it with a so-called republican veneer in the eyes of bourgeois commentators and politicians only shows to what extent French mainstream politics has moved to the right. Indeed, the FN’s racism was legitimised by the state, the mainstream parties and by a whole coterie of intellectuals, professors and journalists who have found in Islamophobia a way to advance their careers. This has led Le Pen to boast that the FN has “already won the ideological battle”. Le Pen only had to modulate the Front National’s discourse to adapt to the new “Islamic” scarecrow, and join a racist front “stretching right from the [Valls] government to the FN and taking in LR”.24

Naturally, the Front National also profits from the long economic crisis and its corollaries—unemployment, inequality and austerity—to woo voters from the working class and the poor who felt cheated by the promises of the mainstream right and left parties that have brought them nothing but more destitution. But the economic tree must not screen the racist forest: “Parts of the left were led to believe that what was at stake with Marine Le Pen’s so-called ‘social turn’ was to unveil…the pro-capitalist nature of the FN”25 at the price of neglecting its racism, the real engine behind the FN’s advance and its ideological cement. As Denis Godard has pointed out, “the whole history of the FN is marked by a double-dealing: turning towards anything that legitimises the Front (parliamentary work, media exposure, reaching out to sections of the right) to widen its appeal, and openly racist and fascist declarations and actions that aim to consolidate and develop an ideologically fascist heart”.26 This tactic, initiated by Jean-Marie Le Pen, was pursued by his daughter Marine during both the 2012 and 2017 elections27 to consolidate and flatter the party’s fascist, antisemitic core.

And what a core! An overly bloated “protection and security department” recruited among veterans of the French army’s imperialist escapades and organised along paramilitary lines through which real links are maintained with smaller Nazi groups, a string of small service provider companies whose owners’ list reads like a who’s who of the 1980s French far-right street-fighting scene, the odd nostalgics of Nazism and the regular antisemites… the Front National remains the undisputed gravitational centre for French fascists. According to Vanina Giudicelli, Marine Le Pen represents a middle way “between those who believe that the time has come to try and take power and those who believe that they are cruelly lacking a mass movement—that is, that it’s not enough to have influence inside the state [the FN is very popular in the police and the military], but that really, to put their political project into action they need a movement that can take it to the streets”.28

The accelerating crisis of the past few years has favoured the proliferation of Nazi street organisations like Génération Identitaire and Bastion Social. With a wide internet audience on the “fachosphere” attracted by antisemitic, homophobic and Islamophobic fantasies and conspiracy theories like the so-called “great replacement” of white Europeans by Muslim migrants, these groups number hundreds of active militants implanted in cities like Lyon, Marseille, Paris, Nantes and others. Focused on anti-migrant campaigns, street pogroms, attacks against left-wing movements and student occupations,29 their actions stem from the classic repertoire of older Nazi groups from whom they descend. Although they are not formally part of the Front National, an Al Jazeera undercover investigation into the Nazi groups has brought concrete proof of what the anti-fascist left had been warning against for a long time: the existence of ideological and organisational revolving doors between the two spheres. A member of Generation Identity even claimed that the “Front National does its work, which is politics. And we do our work, which is the streets”.30 This implicit division of labour, which does not need to be actively coordinated, is apparent in the patterns of intervention of the far-right in the Yellow Vests movement, to which we will return later.

Who are the Gilets Jaunes?

The question of who the Gilet Jaunes are tormented the left in the weeks running up to 17 November; a movement against “green taxes”, growing outside the left—outside unions, even outside known social media networks—whose only known spokespeople dangerously leant towards the far right, taking hold in small town and rural areas with a strong FN presence. Fears, both legitimate and fantastical, of the emergence of a mass petty-bourgeois reactionary movement dominated the left in the run-up to the first day of mobilisation. Thankfully, those fears were soon proven wrong.

The Gilets Jaunes are majority working class people organising outside the workplace and independently of existing working class organisations such as trade unions, political parties and other associations. Studies show that the working class, as well as the unemployed, form the bulk of those who declare themselves supportive of the mobilisation. A study found that 62 percent of the mobilised Gilets Jaunes had a negative balance on their bank account at the end of every single month.31

The working class Gilets Jaunes, including retired and unemployed workers, organised geographically and initially focused their grievances on a wide range of fiscal demands: reverting tax cuts for the very rich, fighting tax evasion, reducing taxes on pensions and essential products and, finally, increasing the minimum wage. Some saw the influence of the petty bourgeoisie behind the movement’s focus on the state and taxation. Indeed, the early phases of the movement saw small business owners join, with their specific grievances around company taxes and taxes on wages. But the subsequent development of the movement, with hundreds of different demands emerging from general assemblies organised democratically all over the country, shows a clear pattern of the predominance of working class concerns such as unemployment, public services, housing and pensions, as well as poverty among working women32 and little to no word on taxes on small firms.

This is clearly and objectively a working class movement driven by those who have found themselves on the receiving end of the economic crisis and its neoliberal “solution” in the past decades. However, the paradox lies in the fact that, first, the demands focused mainly on taxation issues and, secondly, national symbols predominated inside the mobilisation.

The early focus on taxes rather than wages, unusual for the traditional labour movement, is symptomatic of a mobilisation outside the—usually small—workplace, which can immediately draw in the unemployed and the retired. This is in the context of the relative retreat (and in some cases, disappearance) of local trade union presence and of the pull that a large, combative workplace can exert on its surroundings. But tax issues are underlined by class: the demands around the reinstatement of the wealth tax, on fighting tax evasion by big multinationals and on public services all concern the state-driven reforms of capitalism that have reduced the working class’s indirect wages and favoured the very rich.

The other, more problematic contradiction concerns the use of nationalist symbols long rejected by the French left and working class movement. French flags, the Marseillaise and “Marianne”—the gendered personification of the French nation—are foreign to the French left and traditionally prevalent on right-wing mobilisations (apart from Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s 2017 presidential election campaign). If it is quite obvious to everyone other than pedantic formalists that the movement is not a fascist or even predominantly nationalist mobilisation masquerading behind social demands, the question remains, how do we interpret the contradiction between the social engine of the mobilisation and its use of national ideological symbols?

In this we can turn to Antonio Gramsci, who, following Karl Marx, affirmed that “the claim that every fluctuation of politics and ideology can be presented and expounded as an immediate expression of the structure, must be contested in theory as primitive infantilism”.33 On the contrary, what is needed is a concrete study of the ideology and the role it plays in people’s actual practice.

The coherent, united French nation that the ruling class invokes to justify its rule is “nothing but a metaphor”. It is in reality akin to the “coexistence and juxtaposition of different civilizations and cultures, linked by state coercion and culturally organised as a ‘moral consciousness’, at once contradictory and ‘syncretic’”.34 This “moral consciousness” appears to be taken for granted by the Gilets Jaunes in their dissent against the ruling class. In their adoption of national symbols and rhetoric, they reproduce a classic phenomenon whereby rebels use the ethical symbols and discourse of the rulers and turn them against them. Martin Luther’s followers rose against the Catholic pope in the name of “true” Christianity, the Gilets Jaunes rise against their rulers using some of the classic symbols with which the heroic 18th century bourgeoisie has burdened its conservative, decidedly unheroic heirs: “Liberty, equality, fraternity”, and a national anthem, the Marseillaise, that smells terribly of revolution. The Gilets Jaunes have thus decreed that the current French rulers have betrayed their own “moral consciousness”, and proclaim themselves to be the “people”, the custodians of a “real France” where this moral consciousness is actually applied.

Naturally, such a France has never existed. While it is not the sign of an inherently racist, reactionary movement, the use of nationalist symbols nevertheless reveals the movement’s weaknesses and limitations: first and most obviously, the French flag and the Marseillaise, while they attract working class people who would never have marched under a party banner, also attract the organised far right like flies to manure.

Second, the use of the French flag, of the national anthem, of an overwhelmingly “French” discourse, betrays the movement’s reformism and a conciliatory approach to class society. What is implied is that the French values of “liberté, égalité, fraternité” and the famous “French social system”, which is being dismantled, can provide the umbrella under which one can have a conciliation between rich and poor and a mitigation of inequalities and antagonisms. France is then seen as an abstract idea, endowed with an almost religious quality which puts it above social classes and history itself.

An evolving movement

But if there is one thing we can learn from the Yellow Vests movement, it is that ideas can change. Ideas change when people start to move, when they stress test in practice the common sense they had hitherto uncritically accepted, thus challenging their own beliefs—such as the existence of an interest common to all French, or the neutral role of the police and the judiciary.

Sociologist Benoît Coquard reminds us that daily life in rural areas, among the centres of the early mobilisations, can tend to “blur class distinctions”, particularly as many workers are employed in small companies where there is a perceived sense of proximity to the boss, which may spill over into the sphere of leisure and cultural life outside the workplace. However, things began to change on the “filtering roadblocks”, a rural, non-workplace equivalent of picket lines where the Gilets Jaunes argue, agitate and try to convince motorists to join their mobilisation: “As cars cross the roadblocks and the roundabouts, we gradually see a dichotomy of the world that emerges between the ‘friendlies’, those who are ‘like us’, and the rich, ‘the fat bourges who don’t give a damn’”.35

The reactions of the “fat bourges” and their representatives alternated between disbelief, hysteria and resignation, particularly when the movement created insurrectionary scenes in central Paris in December, sending shockwaves around the world. Philosopher and former education minister Luc Ferry urged the police to “use their weapons once and for all”, while gender equality minister Marlène Schiappa, the feminist, liberal face of Macronism, reacted to the crowdfunding campaign in favour of Christophe Dettinger, the “boxer of CRS”,36 by demanding a register of the 9,000 contributors.

But the most lucid and telling reaction came from Xavier Bertrand, also a former minister, who sighed that “Sarkozy did not win a second mandate, Hollande couldn’t even run, and now we are wondering whether Macron will be able to finish his term”.37 Some of Macron’s MPs, who won’t risk showing their faces in their own constituencies, have attempted a diversion by attacking the high-ranking civil servants of the ministry of finance at Bercy and branding them responsible for Macron’s tax policies, just as the latter was yielding and announcing concessions. A series of articles by Le Monde have revealed the disarray at the top of the ministry: “If the Gilets Jaunes’ demands have provoked such emotions among Bercy’s cadres, it is because they thought their hour had finally come with Macron’s election. A former finance ministry inspector reaching the Elysée, what a triumph! ‘He knew how to talk to us, he understood us’, a member of the administration explains”.38

The movement alternates roadblocks and roadside pickets during the week before converging on local cities for the traditional Saturday demonstration. The savage violence of the police and the judiciary’s expedited severity, the contempt that spurts from columnists and editorial boards and the outright rage of the very rich and their pundits, and every one of the movement’s jerky steps forward reveals unpleasant truths about society. Police repression in particular acts as a catalyst for political consciousness, as it is directly experienced by hundreds of thousands and witnessed via social media by millions of sympathetic supporters of the movement. One of the many turning points was a video which emerged in December of hundreds of high school students from Mantes-la-Jolie, a suburb of Paris, forced to kneel for hours and sneered at by the police who had arrested them en masse for blocking a road outside their school. In normal times, those overwhelmingly black and Muslim students are typically on the receiving end of the everyday violence of the French state under the cover of racism. But these are not normal times: while ministers and their media lackeys recycled their old racist talking points about the “banlieues thugs”, white Yellow Vest demonstrators all over the country kneeled in front of police lines in solidarity with their unlikely suburban comrades.39

Concrete developments have nailed questions of class, police violence and the role of the state to the centre of debates, positioning the movement on favourable ground for the radical left. Naturally, it is quite useless to stand on favourable ground without an army: the initiative actively to intervene in the Gilets Jaunes movement came not from the traditional, politically passive far-left organisations, but from a recently formed anti-racist group, the “Comité Adama”. Formed in 2016 in reaction to the killing of black youth Adama Traoré at the hands of the police in a Paris suburb, this group has since put itself at the centre of the fight against structural racism and police violence. As Adama’s sister Assa Traoré said: “who can better speak of poverty and unemployment than us who live in the suburbs? The police who are mutilating the Gilets Jaunes today spent decades training on impoverished Black and Arab youths.” Cutting through the pedantic debates about the “true nature” of the movement, she declared: “Our legitimate place is in this movement. Either we join or we run the risk of allowing this movement to be turned against us by the far right”.40 Thus on 1 December in a barricaded Paris, a thousands-strong far-left contingent brought together the Comité Adama and its close allies (notably the “Collectif intergare”, a group of radical railway workers forged in the 2017 strike and autonomous anti-fascists) with more traditional organisations such as the Nouveau Parti anticapitaliste (NPA) to join the Yellow Vests demonstration that day.

The explicitly political intervention by the far left in Paris, emulated across the country, is of crucial importance given the far right too is attempting to lead the movement. In its early days, it appeared that the movement’s poor, predominantly rural anchorage perfectly fitted the Front National’s rhetoric of the “forgotten France” outside the large cities. The presence of petty-bourgeois elements and their lumping together of billionaire bankers and poor “benefits profiteers” in the category of “parasites” also echoed a classical fascist discourse. An early study showed that there were as many Le Pen as Mélenchon voters mobilised under a yellow vest (although abstentionists and blank voters were even more numerous).41 In some instances openly racist actions were undertaken; some Gilets Jaunes called the police on migrants hidden inside a truck they had stopped, and others blockaded a company that had apparently “hired three immigrants instead of locals”.

So racists and Le Pen voters are mobilised, but even their “engine” is social demands. This puts Le Pen herself in an embarrassing position: on the one hand, she publicly supports the movement against the “elites”; however, the Front National cannot put its money where its mouth is when it comes to social justice demands. Le Pen, who is only too aware of her core petty-bourgeois base, had to repeat her opposition to any increase to the national minimum wage publicly. She also declared: “I suppose the movement has to stop now” after the terrorist attack on the Strasbourg Christmas market in December, and finally she felt compelled to remind readers that “people also speak of immigration on the roundabouts you know” in an interview in far-right publication Causeur. This is undoubtedly true because social demands are not a magic wand that makes racism disappear, but the predominance of the former as well as the growing popular resentment against the police has thrown the ball out of the FN’s court. Where the FN has tried ostentatiously to support the Gilets Jaunes, like in former mining areas in the North where it holds four MP seats and a city council, the movement has died down.42

The other far-right intervention in the movement comes from the smaller, street-oriented fascist groups. They have notably attempted to “solve” the question of violence during demonstrations by coordinating with the police and investing a self-proclaimed “Service d’Ordre” (steward and security service) for the demonstrations; naturally they used this position to try and play on the movement’s desire to remain “politically neutral” in order to kick the trade unionists off the demonstrations.43 However, this has backfired as many individuals forming the SO were identified by the media (with the help of radical left activists) as fascists. Therefore their preferred mode of intervention has been direct action in Lyon, Nantes, Toulouse, Marseille, Bordeaux and of course Paris, where they have attacked far-left activists including the NPA contingent on 27 January.

Almost every Saturday demonstration is the scene of serious street fighting between the fascists and mostly autonomist anti-fascist groups, both having grown on the back of the struggles and the accelerating crisis of the past few years. While the fascist groups need to be physically kicked out of the Gilets Jaunes protests, the culture of secrecy inherent to the autonomists means that they seldom provide any political cover for their direct actions. The Gilets Jaunes movement nevertheless offers a concrete opportunity to develop a united front tactic which complements physical confrontation with a political mobilisation, through “the diffusion of a mass anti-racist and anti-fascist message, revealing to every Gilet Jaune the truth about these Nazi groups and explaining why they need to be kicked out of protests by any means necessary”.44 However, when it comes to fighting fascism, traditional organisations stick to commonplace platitudes with no real follow-up in practice,45 which means that autonomist groups remain the only significant force on the left to propose a veneer of strategy to deal with the fascist danger.

On the eve of 17 November, the first Gilets Jaunes day of action, the CGT’s general secretary Philippe Martinez explicitly dissociated his union from the coming movement, stating that it was “impossible to imagine the CGT marching together with the Front National” and accusing bosses of manipulating an anti-tax mobilisation. He reflected the uneasiness with which the radical left and the labour movement apprehended a movement mobilising outside their traditional bases, and which appeared to be driven by social media networks harbouring suspicious links to the far-right. In return, a certain mistrust of trade unions seemed to pervade among Gilets Jaunes wary of seeing their “citizens movement” hijacked by any organisation.

The initial convergence had to be driven from below, through gradual and careful small steps. On 22 November, oil refinery workers went on a national strike to put pressure on their bosses during annual salary negotiations. In the southern Bouches-du-Rhône department, strikers joined Gilets Jaunes who had been manning a day and night filtering blockade outside their Total refinery, marking the first implicit convergence between trade unionists and Gilets Jaunes.46 As a reporter remarked, each side initially stood on opposite sections of the same roundabout, sending out scouts to break the ice. In the port town of Saint-Nazaire, a traditional bastion of working class struggle, the Gilets Jaunes occupied an empty building in late November to turn it into a “people’s house”. When the city council sent a bailiff to summon the occupiers to evacuate the premises, the dockers’ union threatened to go on strike; “la Maison du Peuple de St-Nazaire” remains to this day the headquarters of the local Gilets Jaunes, a place where working people come together and catch themselves red-handed dreaming of a different society:

I find myself with youngsters who have fought on the ZAD [zone d’aménagement différée, a radical movement against a new airport near Nantes]. I’ve never really understood the meaning of their struggle, and I still don’t, to be honest. But we are here together, we debate, we yell at each other and we embrace. What is going on between us, this solidarity, I’ve never seen anything like it. It’s unbelievable. It has become like a drug.47

There were signs that the government was wary of any significant convergence too. When truck drivers’ unions put out a strike notice in early December around the payment of overtime, the labour minister herself quickly intervened in favour of the workers to scuttle the strike.

On 13 December, an open letter was published by dozens of CGT shop stewards stating that:

Our friends and colleagues are wearing yellow vests. Often, they are precarious workers, far from the large cities, working in small companies or out of work. They are working people who, like us, cannot make ends meet. They are in large parts those whom we fail to organise in our unions, to drag along in our usual struggles, to mobilise under our slogans. Must we not ask why?48

This reflected a growing sentiment among militant trade unionists, who were alerted by the outcome of a meeting between a weakened Macron and national trade union leaders after a particularly riotous Saturday mobilisation in Paris, which managed to extort a common press statement “condemning violence”.

Martinez in particular is caught in the classical trap of the trade union bureaucrat, torn between his position as a credible interlocutor of the government and being at the head of what is by far the largest combative trade union in France. Although he has generally adopted a more confrontational attitude than his predecessor, given the scale of the attacks of the past few years, he is wary of calling for an indefinite mobilisation as he knows the CGT cannot carry it on its own. The fact that the other large union confederation, the CFDT, is backing the government, seems to condemn Martinez to the almost apologetic, passive attitude of calling for punctuated days of trade union mobilisation, on 5 February and 19 March.

But, regardless of oscillations at the top, the Gilets Jaunes movement has heightened the country’s political temperature and created favourable conditions for local strikes over bread and butter issues. In a speech after the December riots in Paris, Macron encouraged bosses to play their part and grant their workers end of year bonuses, in return for tax exemptions on bonuses up to €1,000. Almost every large French multinational, flush with cash and anxious to help a weakened Macron, has answered his call, but other bosses have not. This has encouraged a mushrooming of “Macron bonus” local strikes in companies with a well-established trade union presence, but not only them: workers at Derichebourg, an Airbus subcontractor, organised themselves in a “collective of angry workers” and went on strike with the belated support of one local trade union section, with two other unions siding with the bosses and citing the workers’ “irresponsible behaviour”49—their picket lines had more Yellow Vests than trade unionists on them. Apple retail workers unexpectedly went on strike on Christmas Eve, revitalising local unions, and ended up winning not a bonus but a permanent wage increase.

These sparse and localised struggles shed light on the labour movement’s future tasks. As the El-Khomri law takes hold, attacks on pay and conditions will come increasingly from within the companies, particularly where the combative trade unions are weak, and will require the local building of resistance. Unions will need to take the task of local building much more seriously and will run into difficulties, but the “Macron bonus” strikes show that the general political situation can diffuse into a multitude of localised struggles that trade unions will need to seize.

A crisis of hegemony

The Gilets Jaunes are the latest symptom of the long organic crisis that the French ruling class is going through. Gramsci described an organic crisis as a long-term economic crisis that the ruling class fails to solve, allowing it gradually to infect the ideological and political field of society and compromising the hegemony of the ruling class.

Among revolutionary Marxists it was indeed Gramsci who most systematically refuted the tendency to reduce the state to its “special bodies of armed men” (police, army, prisons, etc) and put forward the ways in which the bourgeoisie gained the consent of the subaltern classes—or at least of a majority within their ranks by claiming for its rule a universal validity that embodies the “common interest” in one way or another. To be sure, the theory of hegemony is a theory of the state, but of a state which is “no longer merely an instrument of coercion, imposing the interests of the dominant class from above. Now, in its integral form, it had become a network of social relations for the production of consent, for the integration of the subaltern classes into the expansive project of historical development of the leading social group”.50

To paraphrase Gramsci’s famous metaphor, the fortress of the bourgeoisie is not only protected by walls patrolled by armed guards, but surrounded with trenches and imbricated mazes which serve to delude and demoralise potential assailants while work goes on as usual inside the fortress. This does not mean, however, that the rulers’ hegemony is an ideological con trick played on the gullible masses, a simple fool’s bargain which must be intellectually exorcised separately from, or in substitution to political struggle directed against the state.51 Rather, ruling class hegemony is secured through what Gramsci called “civil society”, a network formed of reformist parties of various types, trade unions, schools and universities, cultural associations, the media, etc, and which appears to give the rulers’ ideology a concrete, material realisation in people’s practical life.

Although this is not the place for a comprehensive critique of Gramsci’s concept of civil society, we must nevertheless ask how today’s rulers maintain their hegemony—and how it is undermined. Writing in 1977, Chris Harman emphasised that advanced capitalism “has been characterised by the phenomenon of ‘apathy’—a falling away of mass participation in political and cultural associations …a centralisation of ideological power, to the atomisation of the masses—with the crucial exception of workplace-based union organisation—and to a weakening of old political and cultural organisations”.52 To this we must add public services and the so-called “welfare state”, which are not—normally—centres of ideological power but serve to give material legitimacy to the ideological claims of the integral state. Indeed, even as they had been wrenched from the ruling class through struggle, the state provision of public services and benefits in France has until recently been central to the ruling class’s political discourse around “the French social model” and the “Republican pact”.

This tendency towards “atomisation” has evidently accelerated in the neoliberal era, undermining the capacity of large trade unions and reformist parties to give expression to popular discontent but also channel it away from the centres of power; in this way they played the role of a safety valve protecting the bourgeoisie from unexpected catastrophic explosions. This had happened most clearly in 1968 when the CGT and the Communist Party were able to defuse the revolutionary potential of what was at the time the largest general strike on record, not without securing, admittedly, significant material concessions from the ruling class.

But this “safety valve” is not only active during periods of open struggle; even as apathy and atomisation progressed, the turning of electoral politics into a national spectacle covered passive consent with the veil of active adhesion, while the secular local implantation of reformist parties, this crucial but often overlooked thermometer, was gradually eaten away.

None of this means that the “special bodies of armed men” will only intervene after all ideological dams have yielded. In Gramsci’s own words:

The “normal” exercise of hegemony on what has become the classic terrain of the parliamentary regime is characterised by the combination of force and consent that balance each other in various ways, without force violating consent too much, even attempting to make force appear to be resting on the consent of the majority, expressed by the so-called organs of public opinion—newspapers and associations—which, therefore, in certain situations, are multiplied artificially.53

The production of majority consent in liberal democracies is therefore constantly combined with the forcible subjugation of a minority, or more precisely of a multitude of minorities under a centralised ideological barrage which aims, if not to gain the acquiescence of the majority, at least to secure its quiet indifference towards repression. State racism evidently plays a crucial role in covering the oppression of a minority while dividing working people.

However, unlike brick and mortar trenches and mazes, civil society is a living organism, a tissue of social and political relations built on an economic base. The long-term economic crisis and its neoliberal “solutions”, which increase poverty and unemployment while shrinking public services, inflates the suffering of the subaltern classes and gradually eats away the credit of civil society and its material and ideological capacity to contain discontent; and thus the integral state’s scale tips more and more towards its repressive apparatus, strengthening it and widening its reach to deal with the multiplied hotbeds of dissent, as is evident since the beginning of the Gilets Jaunes movement.

Conclusion

This article’s emphasis on Macron’s weakness has stemmed from an analysis of the historic phase of class struggle in France which can be summed up as follows: Macron’s election came at a period when a radicalised ruling class was in dire need of further neoliberal reforms given the decline of French capitalism compared to its international rivals—that was Macron’s historic task. At the same time, the reforms of the past few decades and the resistance put up by the working class have gradually discredited the traditional parties of the ruling class, leading to their catastrophic collapse in 2017. This left it to Macron to enact further violent reforms over a political field that is increasingly polarising between the far right and the far left. In other words, the French ruling class was preparing for a full-scale assault on workers and the poor, but without its traditional hegemonic political tools which it had been forced to sacrifice in previous battles. Does this not constitute a recipe for crisis?

Having said that, the scale, depth and endurance of the Gilets Jaunes movement surprised everyone—it showed how deeply the resentment against the ruling class, personified by the arrogant Macron, is rooted in popular soil. Whatever the future may hold for it, the movement has brought hundreds of thousands of working people out of apathy, atomisation and demoralisation, and onto the stage of history. A thousand times more effectively than far-left propaganda, the Gilets Jaunes revealed in practice and to a whole nation the ugly, coercive face of the state, of its police and its judiciary, as well as the class contempt and sheer hatred with which the bourgeoisie and its media lackeys consider the working masses. The Gilets Jaunes have also mercilessly lifted the veil on the weaknesses of our camp. It is a bitter irony of history, in a period so favourable to the dissemination of revolutionary ideas and practice, a period where whole sections of the working class are, consciously or not, looking for anti-capitalist answers, to see the traditional anti-capitalist left in a state of apathy and disorganisation, decidedly incapable of rising to the historical occasion.

The crisis of the centre, of which the Gilets Jaunes are a symptom and an accelerator, can also benefit the far right. If they have nullified the most alarmist predictions that saw in them the new face of fascism, one could not expect the Gilets Jaunes to be impermeable to racism. That is why the intervention of the anti-racist far left was so important, and should serve as a stepping stone for the construction of a wide anti-racist united front to confront the Front National and the smaller fascist groups.

So revolutionaries have an uphill battle ahead of them to rebuild their organisations and advance an anti-racist and anti-fascist agenda, but the task is far from desperate. In spite of the formal defeats of 2016 (El-Khomri) and spring 2018 (railway strike), the chapter opened by the struggle “against the labour law and its world” is far from over. The momentum gathered in 2016, 2017 and 2018 has defined the left’s uneven but enthusiastic intervention in the Gilets Jaunes movement, and will continue to grow as class antagonisms and the generalised political crisis intensify in the coming months and years.

Jad Bouharoun is a Middle Eastern revolutionary socialist living in France.

Notes

1 Howell, 2018.

2 Howell, 2018.

3 Fine, 2008, p15.

4 Nicolas, 2010.

5 “Apache”, 2012.

6 Dares Analyses, 2017.

7 OECD, 2018.

8 Rigouste, 2016.

9 Béroud, 2009. This is especially the case in manufacturing.

10 Dares Analyses, 2018.

11 ILO and OECD, 2015.

12 Agnew, 2018.

13 WSI, 2015.

14 Meistermann, 2016.

15 In 2015, the 1.3 percent of business sector companies that saw strikes or work stoppages employed 24.4 percent of the total workforce—the ratio was 1.7 percent and 26 percent respectively for 2016—Dares Résultats, 2018.

16 Howell, 2018.

17 Dares Résultats, 2018.

18 CGT Pôle économique, 2017.

19 Sénécat, 2018.

20 Palheta, 2016a.

21 Béroud, 2018.

22 Speech before CEOs organised by Fondation Concorde, 9 March 2016. Go to www.youtube.com/watch?v=iaaEICTmebs

23 Soudais, 2017.

24 Palheta, 2016b.

25 Godard, 2012.

26 Godard, 2010.

27 After the first round of the presidential elections of 2017, Le Pen appointed a Holocaust denier to head her party and declared that the state bore no responsibility for the 1942 “Vel’ d’Hiv roundup”, when thousands of Jews were snatched by the French cops and sent to Nazi death camps.

28 Giudicelli, 2017.

29 Flo and Adrien, 2018.

30 Al Jazeera, 2018.

31 Collectif “Quantité critique”, 2018.

32 Goanec, 2019.

33 Hoare and Nowell Smith, 1971, p407.

34 Gramsci and Keucheyan, 2012, p55.

35 Quoted in Duquesne, 2018.

36 Professional boxer Dettinger was filmed fighting riot police bare-handed on 5 January 2019 during a Gilets Jaunes demonstration in Paris.

37 Belouezzane, 2018.

38 Tonnelier, 2019.

39 As an old anarchist exclaimed to a rally in the suburb of Saint-Denis: “We are living through crazed times! Who would’ve thought that demonstrators carrying French flags would express solidarity with suburban youths against the police?”

40 Speaking to a mass meeting at the Bourse du Travail of St-Denis on 6 December 2018.

41 Collectif “Quantité critique”, 2018.

42 Bonnet, 2019.

43 Flo and Jad, 2019.

44 Flo and Jad, 2019.

45 Salingue, 2019.

46 Le Figaro, 2018.

47 Weiler, 2019.

48 Mathieu, Defresne, Kubecki, Tormos, and others, 2018.

49 Balestrini, 2019.

50 Thomas, 2010, p143.

51 Chris Harman wrote of “would-be intellectuals who want to pretend they are fighting the class struggle through ‘a theoretical practice’, ‘a struggle for intellectual hegemony’, when in fact they are only advancing their own academic careers”—Harman, 1977.

52 Harman, 1977.

53 Gramsci, 1971, p80.

References