A review of Anwar Shaikh, Capitalism: Competition, Conflict, Crises (Oxford University Press, 2016), £35.99

Anwar Shaikh is one of the world’s leading economists who draws on Karl Marx and the classical economists (“political economy”, if you like). He has taught at New York’s New School for Social Research for more than 30 years, and authored three books and six dozen articles.1 This is his most ambitious work. As Shaikh says, it is an attempt to derive economic theory from the real world and then apply it to real problems. He applies the categories and theory of classical economics to all the major economic issues, including those that are supposed to be the province of mainstream economics, like supply and demand, relative prices in goods and services, interest rates, financial asset prices and technological change.

A classical approach

Shaikh says that his approach “is very different from both orthodox economics and the dominant heterodox tradition”.2 It is the classical approach as opposed to the neoclassical one. In other words, he rejects the approach that starts from “perfect firms, perfect individuals, perfect knowledge, perfectly selfish behaviour, rational expectations, etc” and then “various imperfections are introduced into the story to justify individual observed patterns” although there “cannot be a general theory of imperfections”. Instead Shaikh starts with actual human behaviour instead of the so-called “economic man”, and with the concept of “real competition” rather than “perfect competition”. This is emphasised in Chapters 3, 7 and 8 in particular.

However, unlike the recent effort of Ben Fine and Ourania Dimakou in their two-volume Microeconomics and Macroeconomics, Shaikh does not conduct a critique of mainstream orthodox economics as such.3 Rather he aims to present a completely alternative economic approach, which he calls “classical”, following the tradition of the first political economists of industrial capitalism, Adam Smith, David Ricardo and Karl Marx.

The book is a product of 15 years work, so it has taken longer to gestate than Marx took from 1855 to 1867 to deliver volume one of Capital. But it covers a lot. All theory is compared to actual data in every chapter, as well as to neoclassical and Keynesian/post-Keynesian arguments. Shaikh develops a theory of “real competition” and applies it to explain empirical relative prices, profit margins and profit rates, interest rates, bond and stock prices, exchange rates and trade balances. Demand and supply are both shown to depend on profitability and interact in a way that is neither Say’s Law nor Keynesian, but based on the classical theory of value. A classical theory of inflation is developed and applied to various countries. A theory of crises is developed and integrated into macrodynamics.

That’s a heap of things. But readers can follow in detail Shaikh’s arguments through a series of 21 video lectures that cover each chapter of the book.4 These can be quite technical in part, but are worth the effort of concentration. See Lecture 15 in particular for Shaikh’s overall summary of capitalism. There are also short interviews with Shaikh on the main message of his book, all nicely compiled by Shaikh on his website.5

There are two basic pivots to his “classical” approach. Firstly, the profit motive, not making things or carrying out services, is seen as the driving force of capitalism: “Capital is a particular social form of wealth driven by the profit motive. With this incentive comes a corresponding drive for expansion, for the conversion of capital into more capital, of profit into more profit”.6

Secondly, the capitalist economy should not be viewed as a “perfect” market economy with accompanying “imperfections”, but as individual capitals in competition to gain profit and market share. Monopoly should not be counterposed to competition, as neoclassical, orthodox, and even some Marxist economists do. Real competition is a struggle to lower costs per unit of output in order to gain more profit and market share. In the real world, there are capitals with varying degrees of monopoly power competing and continually changing as monopoly power is lost with new entrants to the market and new technology that cuts costs. Real competition is an unending struggle for monopoly power (dominant market share) that never succeeds in total or forever: “each individual capital operates under this imperative…this is real competition, antagonistic by nature and turbulent in operation. It is as different from so-called perfect competition as war is from ballet”.7

A theory of value: classical or Marxist?

Shaikh’s work, with his analysis of crises under capitalism and his avowed support for Marx’s theory of value, has usually been considered as part of the Marxist tradition. But it is no accident that Shaikh does not want to be called a Marxist economist or for his Capitalism to be seen as a modern Marxist critique following Marx’s own similarly titled work (although Marx never used the word “capitalism”, only “capital”). Instead Shaikh subsumes Marxist theory into classical theory and attempts to bridge the gap between Marxist economic analysis and that of the major classical economist of modern capitalism, David Ricardo,8 along with the theories of Piero Sraffa, the 20th century “neo-Ricardian”.

Sraffa’s aim was similar to Shaikh’s: to draw on and reconcile Ricardo’s theoretical constructs with those of Marx. But the reality was that Sraffa dropped a theory of value (what things are worth and priced at) that was based on the labour time involved in producing them and instead went backwards into measuring things (and services?) by the physical amount of commodities and inputs that go into a new product. Thus Sraffa’s key work is not for nothing called The Production of Commodities by Means of Commodities.9

Sraffa breaks entirely with Marx’s theory of value and as a result is really unable to explain the nature of capitalist production as a process of exploitation for profit initiated by the input of money capital to employ labour to produce commodities that make more money. For Marx, the capitalist production process is M–C–P–C'–M' (where “M” stands for money, “C” for commodity, and “P” for production, where labour is put to work). Thus money makes more money (value) but only because of labour expended to create more value. Sraffa’s process is C–C'. For Sraffa, the role of labour disappears—it is just another “commodity”.

Marx greatly valued the work of Smith and Ricardo for their objective recognition that only labour creates value. But he was highly critical of their failure to see that through systemically. Smith was illogical. With one hand, he recognised that labour created value, but when he came to calculate value in a national economy, he reckoned that value should be added up from wages for labour, profits from capital and rents from land. And the underlying source of value was subsumed, while the accumulated capital used up in fixed assets and raw materials was ignored.

Marx exposed Ricardo’s failure to explain how prices for individual commodities differed from the labour time going into them. The answer of Sraffa and the neo-Ricardians was to drop the labour theory of value; Marx’s solution was to show that values of commodities are transformed into prices of production by the equalisation of profit rates across the economy through competition among individual capitals. Thus total value in an economy would equal total prices, but individual values would diverge from individual prices, depending on the size and composition of the capital invested and the average rate of profit.

Shaikh knows this and is very vocal in his theoretical and empirical analysis in the book to show that Marx’s solution was right and provides the best understanding of the movement of prices in the capitalist economy. But he also adopts a version of the Sraffian production process that cannot be reconciled with Marx and, more important, which fails to provide a logical explanation of capitalist production.

Fred Moseley, in his excellent new book, Money and Totality, provides an analysis of Marx’s logic in Capital and his method of transforming value embedded in commodities into prices in the market.10 Moseley takes up the contradiction in Shaikh’s position. In earlier works Shaikh argued that, by a multi-step “iterative” process (that he reckoned Marx also used), total value can eventually equal total prices, although total surplus value in an economy will not equal total profit (contrary to Marx) unless we add in profit held by capitalist households outside the production process. So Shaikh starts with Sraffa’s approach of profit as “surplus product” and tries to deliver the Marxist transformation of values into prices—unsuccessfully in Moseley’s view.

It is interesting to find that in Shaikh’s Capitalism, the “iterative solution” has been replaced by one based on another classical economist, James Steuart,11 and on another revisionist “new interpretation” proposed by Marxist economists Gerard Duménil and Duncan Foley,12 which in Moseley’s view (and that of Andrew Kliman13) also fails to interpret Marx correctly. Shaikh, unnecessarily in my view, adopts Steuart’s “crucial insight” that there are “two sources of aggregate profit, profit on production and profit on transfer”. This is clearly contradictory to Marx’s own transformation of values into profit, where there is only one source of profit: surplus value in production.

This all sounds complicated—does it matter that Shaikh attempts to reconcile Marx’s theory of value with that of Steuart and the neo-Ricardian Sraffa? Well, yes and no. The prodigious empirical work by Shaikh in many chapters of Capitalism appears to follow Marxist categories and delivers compelling support for the Marxist economic analysis of capitalism over the mainstream approach. For example, Shaikh delivers deep empirical evidence to back up his theory of real competition leading to an equalisation of profit rates across sectors, as Marx argued, over cycles of “fat and lean years”.14 This leads to a critique not only of mainstream theory à la Paul Samuelson15 that profit rates will rise with new technology, but also of the neo-Ricardian theory of Nobuo Okishio16 and of Sraffa.17

On the other hand, if Marx’s value theory is superseded by classical theory or “corrected” by neo-Ricardians, it opens the door to a rejection of exploitation for profit as the underlying driver of capitalism (which Shaikh holds to, but Smith, Ricardo and Sraffa did not), and undermines Marx’s theory of crisis, based on his law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall. Indeed, Marx’s law is never spelt out in the 759 pages of Capitalism. And the term, the “organic composition of capital”, is never used in explaining how profitability moves under capitalism. So we get an interesting, if ambiguous, suggestion that the empirically falling rate of profit can be explained “in neoclassical terms, as a falling average productivity of capital”, in Marxist terms as due to rising “money ratio of constant capital to living labour” and in Sraffian terms as a reduction in the maximum rate of profit (surplus product).18 But which is the right explanation?

Empirical backing

Moreover, Shaikh attempts to verify empirically the Ricardian argument that prices of individual commodities equal their values in labour time by showing that empirically they nearly do; they are only 7 percent out.19 This is an interesting observation that has been attacked by others.20 Trying to reconcile the Sraffian transformation of prices with Marx’s values to prices leads to an attempt empirically to say that total profits are “nearly” equal to total value (by just 1.6 percent).21 Thus, according to Shaikh, “the real difference between Marx’s and Sraffa’s prices is [just—MR] one of the degree of sensitivity”.22

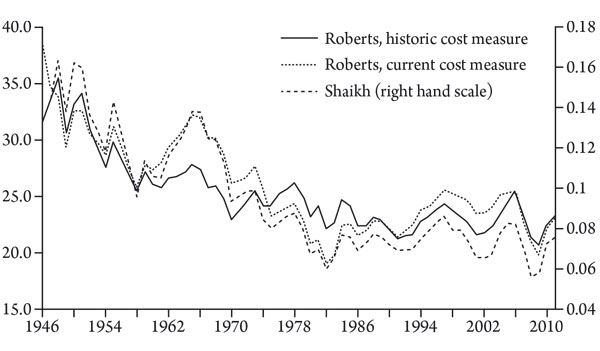

Nevertheless, Shaikh is keen to measure the profitability of capital à la Marx because he recognises that it is essential in understanding booms and slumps (and longer waves) under capitalism. So he measures profit and capital (in the United States) with care and precision.23 He makes some important adjustments to the official (US Department of Commerce) data by adding in interest to corporate profit and widening the definition of capital to include inventories and adjusting more accurately for depreciation. The result is that Shaikh confirms what many others before (including him) have shown—the profitability of corporate capital in the US has been in secular decline since the end of the Second World War with only a moderate stabilisation or recovery from the early 1980s in the so-called neoliberal era.24

In best modern practice, like Thomas Piketty with his book with a similar title (but an entirely different objective and method), Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Shaikh provides all the data used and worked up in the book online for others to follow and/or replicate.25 I ran Shaikh’s data for the US rate of profit against my own calculations (which use different assumptions, which is why the actual rate of profit differs)—see figure 1. Shaikh uses current cost measures of fixed capital contrary to the view of Kliman (and myself) who use historic costs.26 But either way the story is much the same; there is a secular decline in US post-war profitability, but with a limited recovery from the 1980s. So perhaps you could argue that the obscure debate over value theory becomes less important when pitched against real data and results.

Figure 1: The US rate of profit: Shaikh and Roberts.

Source: Author’s calculations.

Exposing the neoclassical and the heterodox

Shaikh takes up every aspect of the capitalist process and in doing so provides Marxist (sorry, classical) answers to the confusions and failures of mainstream economics. For example, his critique of Ricardo’s theory of comparative advantage as a justification for “free trade” benefiting all despite the obvious evidence to the contrary is terrific. In the US the big losers from the current wave of globalisation have been the working class, as Branko Milanovic of the City University of New York details in his new book, Global Inequality.27 Jobs will go as more efficient economies take trade share from the less efficient and with open markets (no tariffs and special restriction or quotas).

But the idea that “free trade” is beneficial to all countries and to all classes is a sacred tenet of mainstream economics. In Chapter 11 Shaikh analyses in detail the fallacious proposition that if each country concentrated on producing goods or services where it has a “comparative advantage” over others (and therefore lower “comparative costs”), then all would benefit. Trading between countries would balance and wages and employment would be maximised. Shaikh shows that this is not only demonstrably untrue (countries run huge trade deficits and surpluses for long periods, have recurring currency crises, and workers lose jobs to competition from abroad without getting new ones from more competitive sectors). Shaikh also explains why it is not comparative advantage or costs that drive trade, but the absolute costs. If Chinese labour costs are much lower than American companies’ labour costs in any market, then China will gain market share, even if America has some so-called “comparative advantage”. What really decides is the productivity level and growth in an economy and the cost of labour:“free trade will lead to persistent trade surpluses for countries whose capitals have lower costs and persistent trade deficits for those whose capitals have higher costs”.28

Although Shaikh’s Capitalism is not a critique of heterodox economic theory, at various places he delivers powerful blows not just to neoclassical theory but also to those heterodox and Marxist analyses that start by accepting the neoclassical view of “perfect competition” as “adequate to some earlier stage of capitalism” and “the necessary point of departure” for an “ever-accreting list of real world deviations” and then seek to amend it.

In particular, Shaikh’s criticisms of post-Keynesian economics, currently the dominant view of leftists in the labour movement internationally, and of the Monthly Review school of “monopoly capitalism”, are persuasive.29 He notes that the MR school considers competition as equivalent to “perfect competition”, thus ruling out capitalism as competitive and leaving us with monopoly capitalism. It’s as though there “was an imaginary golden age of perfect competition that at some time somehow metamorphosed itself into the monopolistic age, whereas it is quite clear that perfect competition has at no time been any more of a reality than it is at present”.30

As Shaikh retorts, the model of the MR school “is not true”.31 “The vision of competition to which the Marxian monopoly capitalism school pledges its allegiance was never valid, not then and not now…and this fact seems to have escaped them entirely”. In the imaginary mode of perfect competition, prices are set for firms; and under the equally imaginary polar opposite, firms are price setters.32 But this is contrary to a Marxist view of real competition “where firms always set prices” and there is a “turbulent equalisation of long-run rates of return of the price leaders”.33 Thus “disorder is its order”.34

Similarly, post Keynesian economics seems to depend at the outset on the imaginary model of “perfect competition”. Prices are costs plus a mark-up and that mark-up depends on the degree of monopolisation.35 Thus post-Keynesian authors argue that price-setting is a symptom of monopoly power. Shaikh counterposes that with real competition whereby firms “always set prices”.36 So capitalism has not changed its spots; the enemy is not monopoly power as such but capitalism, which is still the same leopard.

Shaikh argues that the failure of heterodox theory to start with real competition but merely try to counterpose perfect competition with monopoly also leads to wrong macroeconomic policy: “what neoclassical economics promises through the workings of the invisible hand of the market, Keynesian and post-Keynesian economics promise through the visible hand of the state”.37

On the macroeconomic front, Shaikh consummately dismisses the post-Keynesian argument that it is the change in the share of wages and profits that matters for crises and not the production of profit. And he dismisses the post-Keynesian view that investment depends on the “expectations” of entrepreneurs or on the expectation of future profits rather than profitability when investment was undertaken or even in some preceding period: “the present is not independent of the past. Just as the future is not independent of the present”.38 Indeed, Shaikh reckons that profitability is “the appropriate foundation for Keynes’s theory”—an argument that is a stretch, in my view.39

Shaikh shows sympathy with George Soros’s theory of “reflexivity”, which assumes that the expectation of profit can affect the actual profit as investment takes place assuming a certain return, only for that expectation to be brought “crashing down to earth” so that the expected rate of profit “fluctuates in a turbulent manner around the mutually constructed center of gravity”.40

Shaikh also delivers his verdict on Thomas Piketty’s rival book on capitalism: “Piketty’s measure of the rate of profit is logically inconsistent.” He excludes capital gains in his profit measure but adds in residential property in his fixed capital. This makes his rate of profit too low and “highly susceptible to fluctuations in the market value of assets”.41 This is similar to the critique presented by me and others that Piketty’s so-called stable rate of return is really a return on financial assets and not on productive ones.42

Profitability and cycles

For me, Shaikh’s book takes off when he deals with the nature of the current economic stage through which capitalism is passing. Shaikh reckons that, on the surface, the last crisis—the Great Recession—might look like a crisis of excessive financialisation. But this fails to identify the real cause of the crisis. Keynesians and post-Keynesians argue that the cause of the current crisis is rising inequality and falling wages, so there is a need to maintain a stable wage share and to use fiscal and monetary policy to maintain full employment. But Shaikh argues that such policies would not work because, at least in the US, the post-Keynesians have got the causes of the crisis wrong. The real cause is the movement in profitability—the dominant factor under capitalism.

The crisis was preceded by a long fall in the rate of profit. The neoliberal attack on labour from the 1980s suppressed wage growth and reduced the wage share in order to stabilise the rate of profit. And the enormous fall in the interest rate in the 1980s that fuelled credit expansion and massive debt finance also served to raise the net (or enterprise) rate of profit. So Keynesian fiscal policy by itself may pump up employment, but it will not restore growth. For growth it is necessary to raise the net rate of profit—and interest rates are already at record lows (and even negative).

Shaikh emphasises that it is profit under capitalism that drives growth. There are cyclical fluctuations in profitability which are expressed in business and fixed capital cycles inherent in capitalist production. The history of market systems reveals recurrent patterns of booms and busts over centuries, emanating precisely from the developed world—crises are normal in capitalism. The key crises under capitalism are “depressions”, such as that of the 1840s, the “Long Depression” of 1873-1893, the “Great Depression” of the 1930s, the “Stagflation Crises” of the 1970s and the Great Global Crisis now.

Shaikh revives the concept of long waves in capitalist production, something first identified by the Russian economist Nikolai Kondratieff and which Shaikh first cited in a paper in 1992.43 In that paper, according to Shaikh, Kondratieff’s main point is that business cycles are recurrent and “organically inherent” in the capitalist system. They are also inherently nonlinear and turbulent: “the process of real dynamics is of a piece. But it is not linear: it does not take the form of a simple, rising line. To the contrary, its movement is irregular, with spurts and fluctuations.”

Kondratieff believed that depressions were linked to long waves: “during the period of downward waves of the long cycle, years of depression predominate; while during the period of rising waves of a long cycle, it is years of upswing that predominate”. In a paper that Shaikh presented in 2014, he brought up to date his analysis of this, which is also developed in Capitalism.44

Shaikh reckons Kondratieff’s long waves have continued to operate, and that this is especially clear when measured by the gold dollar price, the key value measure in modern capitalism. He reckons that prices of commodities became a poor indicator of Kondratieff cycles in the post-war period of the 20th century and now looks to the gold price. Shaikh presents a graph of these waves as measured by the gold price of commodities.45

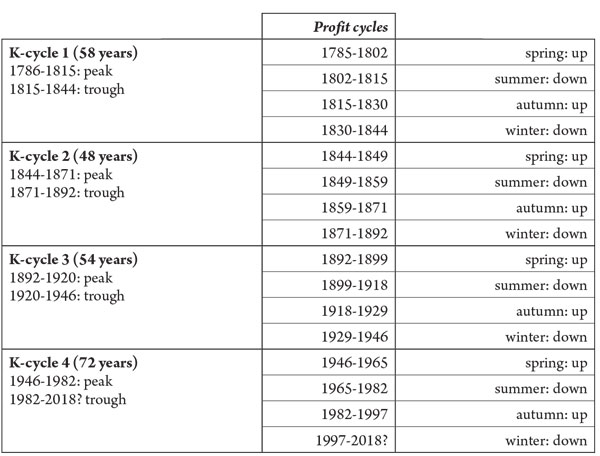

In my analysis, first outlined in my book The Great Recession, I found that the movement of interest rates also provides a very good proxy indicator of Kondratieff waves because it follows the movement in production prices. Kondratieff waves can also be synchronised with profit waves or cycles as in table 1.46

Table 1: Kondratieff cycles and profit cycles

Source: Roberts, 2016c.

So Shaikh’s position is similar to my own on the causes of capitalist crises, the nature and existence of depressions, and the role of Kondratieff and profit cycles.47 It is no accident that both of us made reasonably early (and independent) predictions of the Great Recession of 2008-9. Shaikh made his as early as 2003; I did so in 2005, when I said:

There has not been such a coincidence of cycles since 1991. And this time (unlike 1991), it will be accompanied by the downwave in profitability within the downwave in Kondratieff prices cycle. It is all at the bottom of the hill in 2009-2010! That suggests we can expect a very severe economic slump of a degree not seen since 1980-82 or more.48

From Capital to Capitalism

Shaikh summarises his main theme “which is that theory is important to an understanding of the economy”.49 He says he has taken a “different path” from modern mainstream neoclassical economics and heterodox alternatives like post-Keynesianism. They start from perfect competition as the model and then arrive at reality by “throwing a bucketful of grits” in the machinery of that model. Shaikh says he starts from a theory of “real competition” and uses it to ground theories of aggregate demand and persistent unemployment with profitability playing the dominant role. He has backed up his analysis with the “relevant empirical evidence” to focus on the real patterns of this “turbulent and dynamic system” that is capitalism. This approach is to be commended even if Shaikh’s own theory may have some shaky areas.

Capitalism is a book for economists and brave activists who want to get a bigger grip on the underlying processes of capitalism. It is a monster of a book (even more than Piketty’s), it is not easy to read (even Marx’s Capital is easier, in my view) and it can be very technical. The book covers a lot of ground on economic theory and empirical analysis, perhaps sometimes with a little too much repetition (and there are some editing and data errors—understandable in such a large book and with such detail). But those readers who stick to the task will be rewarded with new insights into the capitalist process and insightful critiques of mainstream and heterodox arguments. If you cannot “wade” through the whole book, at least read the opening introduction to whet your appetite and the comprehensive summary and conclusions.50

Next year will be the 200th anniversary of David Ricardo’s main work of political economy, which laid the theoretical foundations for the classical tradition that Shaikh adheres to in Capitalism. But it will also be 150 years since Karl Marx published volume one of his Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Last year we had the opus from Thomas Piketty that became a bestseller and replaced Stephen Hawking’s A Brief History of Time as the most bought but least read book ever.51 This year Anwar Shaikh’s Capitalism will get less media praise, but it will be read much more than Piketty’s, even if Marx’s Capital still remains the most prescient analysis of the capitalist mode of production.

Michael Roberts blogs at thenextrecession.wordpress.com and his facebook site can be found at http://tinyurl.com/MichaelRobertsFB. His new book, The Long Depression: Marxism and the Global Crisis of Capitalism, is published by Haymarket Books.

Notes

1 Go to www.newschool.edu/nssr/faculty/?id=4e54-6b79-4d77-3d3d

2 Shaikh, 2016, p4.

3 Fine, 2016; Fine and Dimakou, 2016. See also Roberts, 2016a, and my forthcoming review of both books in International Socialist Review, fall 2016.

4 Go to www.hgsss.org/anwar-m-shaikh-capitalism-competition-conflict-and-crises/

5 Go to http://realecon.org/

6 Shaikh, 2016, p259.

7 Shaikh, 2016, p259.

8 Ricardo, 2004.

9 Sraffa, 1960.

10 Moseley, 2015. See also Roberts, 2016b.

11 Shaikh, 2016, pp221-224. Steuart was also discussed by Marx in part one of Theories of Surplus Value—Marx, 1863.

12 Foley, 1982; Moseley, 2015.

13 Kliman, 2006.

14 Shaikh, 2016, pp301-313.

15 Samuelson, 1957.

16 Okishio, 1961.

17 Shaikh, 2016, p320, note 36.

18 Shaikh, 2016, p251.

19 Shaikh, 2016, pp413-416.

20 See Kliman, 2006.

21 Shaikh, 2016, p433.

22 Shaikh, 2016, p437, note 18.

23 Shaikh, 2016, pp243-256.

24 See Roberts, 2015a.

25 Go to http://realecon.org/data

26 See Roberts, 2011, and Basu, 2012.

27 Milanovic, 2016; see also Milanovic’s website at http://glineq.blogspot.co.uk/

28 Shaikh, 2016, p514.

29 Shaikh, 2016, p355.

30 Schumpeter, 1947, p40.

31 Shaikh, 2016, p356.

32 Shaikh, 2016, p363.

33 Shaikh, 2016, p363.

34 Marx, 1847.

35 Shaikh, 2016, p360.

36 Shaikh, 2016, p363.

37 Shaikh, 2016, p235.

38 Shaikh, 2016, p594-595.

39 Shaikh, 2016, p745, and Roberts, 2013a.

40 Shaikh, 2016, p608.

41 Shaikh, 2016, p759.

42 Roberts, 2015b.

43 Shaikh, 1992.

44 Shaikh, 2014; Shaikh, 2016, pp724-745.

45 Shaikh, 2016, p727, figure 16.1.

46 Roberts, 2009.

47 Roberts, 2013b.

48 Roberts, 2009.

49 Shaikh, 2016, p745.

50 Shaikh, 2016, pp3-56 and pp746-759.

51 Roland, 2014.

References