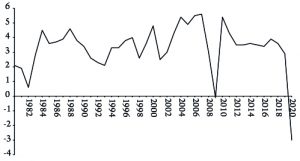

Around 2.7 billion workers worldwide have been affected by full or partial lockdown measures to combat the coronavirus pandemic—around 81 percent of the world’s 3.3 billion workforce. The world economy has seen nothing like this. Nearly all economic forecasts for global gross domestic product (GDP) in 2020 are for a contraction much worse than in the Great Recession of 2008-9 (figure 1).

Figure 1: Global real GDP growth (percentage)

Source: International Monetary Fund data.

During the lockdowns, output in most economies will be found to have fallen by a quarter according to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), with the effects felt in sectors amounting to a third of GDP in the major economies. For each month of containment, there is a loss of 2 percentage points in annual GDP growth. Kenneth Rogoff, co-author with Carmen Reinhart of work on the history of economic crises, reckons that the short-term collapse in global output is likely to rival or exceed any recession in the past 150 years.1 International Monetary Fund (IMF) chief Kristalina Georgieva projects that “over 170 countries will experience negative per capita income growth this year”.2 Investment bank JPMorgan’s economists predict that the pandemic will cost the world at least $5.5 trillion in lost output over the next two years, greater than the annual output of Japan. And that would be lost forever. That is almost 8 percent of GDP through to the end of next year. The cost to developed economies alone will be greater than that lost in the recessions of 2008-9 and 1974-5 combined. Furthermore, the Bank for International Settlements has warned that disjointed national efforts to contain the pandemic could lead to a second wave of cases that would leave the GDP of the United States close to 12 percent below pre-virus level by the end of 2020. That would be far worse than in 2008-9. One recent study argues that the lockdowns in the US will leave production 25-28 percent below normal levels in the short run. Employment there had already fallen by 30 million by the end of April.3

In my 2016 book The Long Depression,4 I found that the loss of GDP from the beginning of the Great Recession in 2008 through the 18 months to the trough in mid-2009 was over 6 percent in the major economies. Global real GDP fell by about 3.5 percent over that period, as the so-called emerging market economies did not contract—mainly because China continued to expand. The Institute of International Finance (IIF), the research body of international banks, now believes that the US will have contracted by an annualised rate of 10 percent by the end of June, and Europe by 18 percent.5

Then there is world trade, which was already falling at a 2 percent annual rate before the pandemic because of weakening economies and the US-China trade war. Now trade is expected to contract by over 13 percent this year, faster than during the Great Recession.6 The collapse in goods trade is particularly damaging to the so-called developing or emerging economies of the “Global South”. Many are exporters of basic commodities such as fuel, industrial metals and agricultural products, whose prices have plummeted since the end of the Great Recession.

Emerging markets disaster

Many larger economies in the Global South—such as Mexico, Argentina and South Africa—were already in a recession when the pandemic hit. Oxford Economics now forecasts that output in emerging markets will fall by 1.5 percent this year, the first decline since reliable records began in 1951. This figure includes the giant economies of China and India. It was their growth during the Great Recession that ensured that there was no average contraction among developing economies then. This time it is different.

As for the smaller emerging economies, the situation is already deteriorating fast. The World Bank believes that the pandemic will push sub-Saharan Africa into recession in 2020 for the first time in 25 years. In its Africa’s Pulse report, the Bank said the region’s economy will contract by 2.1-5.1 percent, compared to growth of 2.4 percent last year, and that coronavirus will cost sub-Saharan Africa $37-79 billion in lost output this year due to trade losses, value chain disruption and other factors.7 More than 90 “emerging” countries, nearly half the world’s nations, have enquired about bailouts from the IMF—and at least 60 have sought to avail themselves of World Bank programmes. These two institutions together have resources of up to $1.2 trillion available to battle the economic fallout but only $50 billion of this can be deployed to “emerging markets”, and only $10 billion to low-income members. These figures are tiny compared with the losses in income, GDP and capital outflows. Since January, nearly $100 billion of capital has flowed out of emerging markets, according to data from the IIF, compared to $26 billion outflow during the global financial crisis of a decade ago. According to Rogoff, “an avalanche of government-debt crises is sure to follow…the system just cannot handle this many defaults and restructurings at the same time”.8 Moreover, the last thing that distressed economies need is another loan from the IMF, as the example of Pakistan demonstrates. The IMF is still demanding austerity measures from the Pakistan government in the middle of this pandemic in return for previous loans.9

In addition to this government debt crisis, there has been a growth of private debt since the Great Recession, and this has been taking place fastest in the so-called developing economies. As a number of economists at the World Bank point out: “Most of the increase in debt since 2010 has been in emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs), which saw their debt rise by 54 percentage points of GDP to a record high of about 170 percent of GDP in 2018. This increase has been broad-based, affecting around 80 percent of EMDEs”.10 Much of this debt is denominated in US dollars, and as that hegemonic currency increases in value as a “safe haven” during the crisis, the burden of repayment will mount for these economies.

There is little room to boost government spending to alleviate the hit. The “developing” economies are in a much weaker position than during the global financial crisis of 2008-9. In 2007, 40 emerging market and middle-income countries had a combined central government fiscal surplus of 0.3 percent of gross domestic product. Last year, the same economies posted a fiscal deficit of 4.9 percent of GDP. The government deficit across “emerging market” economies in Asia went from 0.7 percent of GDP in 2007 to 5.8 percent in 2019; in Latin America, it rose from 1.2 percent of GDP to 4.9 percent; and in Europe it went from a surplus of 1.9 percent of GDP to a deficit of 1 percent.

So the pandemic heralds a global depression for “developing” economies. Global unemployment is also rocketing. The International Labour Organisation (ILO) believes that the global loss of working hours will be equivalent to 305 million full-time jobs. More than 400 million enterprises—made up of companies and self-employed people—are in “at risk” sectors such as manufacturing, retail, restaurants and hotels.11 Underemployment is also expected to increase on a large scale. And, as witnessed in previous crises, the shock to labour demand is likely to translate into significant downward adjustments to wages and working hours. The loss in labour incomes could reach $3.4 trillion. The strain on incomes resulting from the decline in economic activity will devastate workers close to or below the poverty line. Under the “mid and high” economic damage projections from the ILO, there will be 20-30 million more people in working poverty than before the pre-Covid-19 estimate for 2020.

There are few or no “safety nets” in these countries. The hit to working people in the advanced capitalist countries from a global slump, even if short-lived, will be severe, especially after years of austerity and wage suppression. For the billions in the “developing” countries, it will be devastating.

A quick recovery?

Nonetheless, mainstream economic forecasters remain optimistic. All foresee a sharp recovery in the second half of 2020. China is recovering fast, the argument goes, and by September the major capitalist economies will bounce back once the pandemic subsides or the authorities are able to contain it (as, at time of writing, they appeared to have done in China, South Korea and Japan).

Optimism has been seen in global stock markets too, particularly in the US. After falling around 30 percent when the lockdowns to contain Covid-19 were imposed, the US stock market jumped back 30 percent in April. There are two reasons. The first is the belief that the lockdowns will soon be over; treatments and vaccines are on their way to stop the virus and the pandemic will soon be forgotten. For example, the US treasury secretary, Steven Mnuchin, has reiterated his view, expressed at the beginning of the lockdowns, that “you’re going to see the economy really bounce back in July, August and September.” Senior White House economics advisor Kevin Hassett stated that by the fourth quarter of 2020, the US economy “is going to be really strong and next year is going to be a tremendous year.”

The second reason is the recent credit injections by the Federal Reserve (the US central bank) and the government’s fiscal measures. However, this slump will not be avoided by central bank largesse or the fiscal packages being planned. Once a slump gets under way, incomes collapse and unemployment rises fast. This has a cascade or “multiplier” effect through the economy, particularly for non-financial companies. This will lead to a sequence of bankruptcies and closures. In spite of this, it is not just government officials and bankers who think that the economic damage from the pandemic and lockdowns will be short, if not so sweet. Many Keynesian economists in the US are making the same point. Larry Summers, who was treasury secretary under Bill Clinton, reckons the lockdown slump was akin to businesses in summer tourist destinations closing down for the winter. As soon as summer comes along, they all open up and are ready to go just as before: “The recovery can be faster than many people expect because it has the character of the recovery from the total depression that hits a Cape Cod economy every winter or the recovery in American GDP that takes place every Monday morning”.12 The leading Keynesian guru Paul Krugman believes that this slump is not an economic crisis but a “disaster relief” situation.13 While there might have to be higher spending now, and an increase in the deficit, once this spending has worked, the economy will return to its previous state and the deficit will be repaid.

The reason for this optimism is that Keynesian theory starts with the view that slumps are the result of a collapse in “effective demand” that then leads to a fall in output and employment. But this slump is not the result of a collapse in “demand”, but of a closure of production, both in manufacturing and particularly in services. It is a “supply shock”, not a “demand shock”.

The “financialisation” theorists of the Hyman Minsky school are also at a loss, because this slump is not the result of a credit crunch or financial crash—although that may yet come.14 This pandemic hit the world economy through supply, not demand as the Keynesians want to claim.15 It is production, trade and investment that stops first when shops, schools and businesses are locked down in order to contain the pandemic. Of course, if people cannot work and businesses cannot sell, then incomes drop and spending collapses, producing a “demand shock”. Indeed, it is the way with all capitalist crises: they start with a contraction of supply and end up with a fall in consumption, not vice versa.

The Keynesians believe that as soon as people get back to work and start spending, “effective demand” (and even “pent-up” demand) will shoot up and the capitalist economy will return to normal. But if you approach the slump from the angle of supply or production, and in particular, the profitability of resuming output and employment, which is the Marxist approach, then both the cause of the slump and the likelihood of a slow and weak recovery become clear.

The tipping point

Covid-19 was the tipping point for the economy. One analogy is to imagine a pile of sand building up to a peak. Grains of sand start to slip off—and then comes a certain point when, with one more sand particle added, the whole sand pile collapses. If you are a post-Keynesian you might prefer calling this a “Minsky moment”, following Minsky’s argument that capitalism appears to be stable until it isn’t—because stability breeds instability. A Marxist would agree that, yes, there is instability, but would add that instability turns into an avalanche periodically because of the underlying contradictions in the capitalist mode of production.

As the British Marxist economist Chris Dillow argues, the coronavirus epidemic is really just an extra factor keeping the major capitalist economies dysfunctional and stagnant. He lays the main cause of the stagnation on the long-term decline in the profitability of capital: “Basic theory (and common sense) tells us that there should be a link between yields on financial assets and those on real ones, so low yields on bonds should be a sign of low yields on physical capital. And they are.” He identifies “three big facts”: the slowdown in productivity growth; the vulnerability to crisis; and low-grade jobs. As he says, “Of course, all these trends have long been discussed by Marxists: a falling rate of profit; monopoly leading to stagnation; proneness to crisis; and worse living conditions for many people. And there is plenty of evidence for them”.16

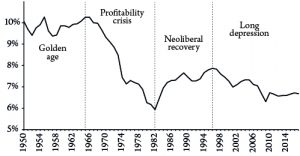

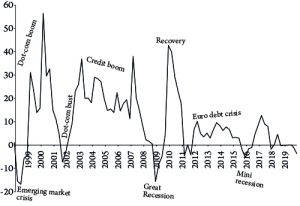

The profitability of capital in the major economies has been on a downward trend (figure 2). Moreover, the mass of global profits was also beginning to contract before Covid-19 exploded onto the scene (figure 3). So even if the virus does not trigger a slump, the conditions for any significant recovery are just not there.

Figure 2: G7 internal rate of return on capital (weighted by GDP)

Source: Penn World Tables 9.1 IRR series, author’s calculations.

Figure 3: Global corporate profits from six major economies (weighted mean, percentage year on year, Q4 2019 partially estimated)

Source: National statistics, author’s calculations.

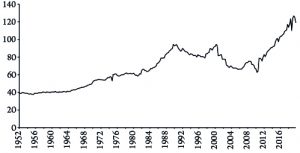

Then there is debt. Over the past decade, characterised by record low, or even negative, interest rates, companies have been on a borrowing binge. Everywhere corporate debt has soared during the long and weak “expansion” since 2009. Huge debt, particularly in the corporate sector, is a recipe for a serious crash if the profitability of capital drops sharply. According to the IIF, the ratio of global debt to gross domestic product hit an all-time high of over 322 percent, close to $253 trillion, in the third quarter of 2019. The rise in US non-financial corporate debt is particularly striking (figure 4). This has enabled large global tech companies to buy up their own shares and issue huge dividends to shareholders, while piling up cash abroad to avoid tax. It has also allowed small and medium-sized companies in the US, Europe and Japan, which have not been making any profits worth speaking of for years, to survive in what has been called a “zombie state”, making just enough to pay their workers, buy inputs and service their (rising) debt, but without having anything left over for new investment and expansion. A recent OECD report says that, by the end of December 2019, the global outstanding stock of non-financial corporate bonds reached an all-time high of $13.5 trillion, double the level reached in real terms in December 2008. As John Plender of the Financial Times puts it:

The rise is most striking in the US, where the Federal Reserve estimates that corporate debt has risen from $3.3 trillion before the financial crisis to $6.5 trillion last year. Given that Apple, Facebook, Microsoft and Google parent Alphabet alone held net cash at the end of last year of $328 billion, this suggests that much of the debt is concentrated in old economic sectors where many companies are less cash generative than big tech. Debt servicing is thus more burdensome.17

Figure 4: US non-financial corporate debt to net worth (percentage)

Source: US Federal Reserve.

The IMF’s latest Global Financial Stability report amplifies this point with a simulation showing that a recession half as severe as that in 2009 would result in companies with $19 trillion of outstanding debt having insufficient profits to service that debt.18 So if sales should collapse, supply chains be disrupted and profitability fall further, these heavily indebted companies could keel over. That would hit credit markets and banks, triggering a financial collapse.

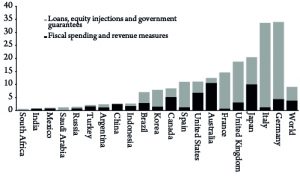

A recent paper by Joseph Baines and Sandy Brian Hager starkly reveals all. For decades, capitalists have been switching from investing in productive assets to investing in financial assets—“fictitious capital”, as Marx called it. Stock buybacks and dividend payments to shareholders have been the order of the day rather than re-investing profits in new technology in order to boost labour productivity. This applies in particular to larger US companies. A vast swathe of small US firms was already in trouble. For them, profit margins have been falling. As a result, the overall profitability of US capital has fallen, particularly since the late 1990s. Baines and Hager argue that “the dynamics of shareholder capitalism have pushed the firms in the lower echelons of the US corporate hierarchy into a state of financial distress.” As a result, corporate debt has risen, not only in absolute dollar terms, but also relative to revenue, particularly for the smaller companies. Everything has been held together because the interest on corporate debt has fallen significantly, keeping debt servicing costs down. Even so, smaller companies are paying out interest at a much higher level than the large companies. Since the 1990s, their debt servicing costs have held more or less steady but they are nearly twice as high as for the top ten percent. Now the days of cheap credit could be over, despite the Federal Reserve’s desperate attempt to keep borrowing costs down. Corporate debt yields have rocketed during this pandemic crisis. A wave of debt defaults is now on the agenda (figure 5). That could “send shockwaves through already-jittery financial markets, providing a catalyst for a wider meltdown”.19

Figure 5: Debt to revenue ratio of US non-financial firms, WRDS Compustat data

Source: Penn World Tables 9.1 IRR series, author’s calculations.

When the optimists talk about a quick V-shaped recovery, they are simply not recognising that Covid-19 is not generating a “normal” recession, and it is not hitting just a single region but the entire global economy. Many companies, particularly smaller ones, will not return after the pandemic. Before the lockdowns, there were anything between 10 to 20 percent of firms in the US and Europe that were barely making enough profit to cover running costs and debt servicing. These “zombie firms” may find the “Cape Cod winter” will be the final nail in their coffins. Several middling retail and leisure chains have already filed for bankruptcy, and airlines and travel agencies may follow. Large numbers of shale oil companies are also struggling. As financial analyst Mohamed El-Erian concludes:

Debt is already proving to be a dividing line for firms racing to adjust to the crisis, and a crucial factor in a competition of survival of the fittest. Companies that came into the crisis highly indebted will have a harder time continuing. If you emerge from this, you will emerge to a landscape where a lot of your competitors have disappeared.20

The mainstream policy reaction

What about the humongous injections of credit made by the central banks around the world, along with the huge fiscal stimulus packages from governments? Won’t that turn things around more quickly? There is no doubt that central banks and even the international agencies such as the IMF and the World Bank have jumped in to inject credit through the purchases of government bonds, corporate bonds, student loans and even more exotic financial assets on a scale never seen before, even during 2008-9. The Federal Reserve’s treasury purchases are already racing ahead of previous quantitative easing programmes. Economists project the central bank’s portfolio of bonds, loans and new programmes will swell to between $8-11 trillion from less than $4 trillion last year. In that range, the portfolio would be twice the size reached following the previous crisis and nearly half the value of US annual output. This would make the central bank’s role in the economy greater than during the Great Depression3 or Second World War. “The Federal Reserve is being sent on a mission to places it has never been before,” according to Adam Tooze, the author of Crashed: How a Decade of Financial Crises Changed the World. He writes that central bank officials “are being sucked into a series of entanglements that they cannot control and that they normally will not touch with a long pole, but this time felt they had to go in, and go in hard”.21

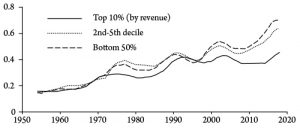

The fiscal spending approved by the US Congress far exceeds the spending programme during the Great Recession. It has reached over 4 percent of GDP in fiscal stimulus and another 5 percent in credit injections and government guarantees. That is twice the amount in the Great Recession, with some key countries ploughing in even more to compensate workers put out of work and small businesses closed down (see figure 6).

Figure 6: Fiscal packages as percentage of GDP as of 12 April 2020

Source: IMF data, author’s calculations.

Most of this largesse is to keep business, particularly big business, alive, rather than to help workers and small businesses. If we take the $2 trillion package agreed by the US Congress, two-thirds of it will go, in the form of outright cash injections and loans that may not be repaid, to big business (travel companies and so on) and to smaller businesses, but just one-third to helping the millions of workers and self-employed people to survive with cash handouts and tax deferrals. It is the same picture in Britain and Europe: first, save big business; second, tide over working people. Moreover, the payments for workers laid off and the self-employed are only expected to be in place for a short period, and often people will not receive any cash for several weeks. So these measures fall short of providing sufficient support for the millions that have already been locked down or have seen their companies lay them off. The reality is that the money being shifted towards working people compared to big business is minimal. For example, the British package offers 80 percent of the wages for employees and the self-employed, but that is no more than the usual unemployment benefits ratio offered by many governments in Europe. Britain had a very low benefit ratio, which is now being raised briefly to the European average. Even then, there are millions who will not qualify.

Yet these cash packages are new. Straight cash handouts by the government to households and firms are, in effect, what the infamous monetarist economist Milton Friedman called “helicopter money”, dollars to be dropped from the sky. Forget the banks; get the money directly into the hands of those who need it and who will spend it. Post-Keynesian economists who have pushed for helicopter money, or “people’s money” as they would prefer it, are thus apparently vindicated.22

In addition, an idea long excluded by mainstream policy has become acceptable: fiscal spending financed not by the issue of more debt (government bonds) but by simply “printing money” (that is, by a central bank depositing money in the government’s account). The policies of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) have arrived. This “monetary financing” is supposed to be temporary and limited, but supporters of MMT are cock-a-hoop, hoping that it could become permanent, as they advocate. Under this approach governments simply create money and spend to take the economy towards full employment and keep it there. Capitalism will be saved by the state and by MMT.23 The problem with this approach is that it ignores the crucial factor: the social structure of capitalism. Under capitalism, production and investment is for profit, not to meet the needs of people. Profit, in turn, depends on the ability to exploit the working class sufficiently compared to the costs of investment in technology and productive assets. It does not depend on whether the government has provided enough “effective demand”.

Michael Pettis, a well-known “balance sheet” macro-economist based in Beijing, challenges the optimistic assumption that printing money for increased government spending can do the trick: “If the government can spend these additional funds in ways that make GDP grow faster than debt, politicians don’t have to worry about runaway inflation or the piling up of debt. But if this money isn’t used productively, the opposite is true.” He adds: “creating or borrowing money does not increase a country’s wealth unless doing so results directly or indirectly in an increase in productive investment… If US companies are reluctant to invest not because the cost of capital is high but rather because expected profitability is low, they are unlikely to respond to the trade-off between cheaper capital and lower demand by investing more”.24 You can lead a horse to water but you cannot make it drink.

The historical evidence shows that the so-called Keynesian multiplier has limited effect in restoring growth, mainly because it is not the consumer who matters in reviving the economy but capitalist companies.25 There is little reason to believe that it will be more effective this time round. A recent study argues that a quick recovery from this pandemic is unlikely because “demand is endogenous and affected by the supply shock and other features of the economy.” This suggests that traditional fiscal stimulus is less effective in a recession caused by our supply shock. Demand may indeed overreact to the supply shock, leading to a demand-deficient recession, because of “low substitutability across sectors and incomplete markets, with liquidity constrained consumers.” This means that “various forms of fiscal policy, per dollar spent, may be less effective”.26

But what else can governments do, and what else can mainstream economists recommend? If the social structure of capitalist economies is to remain untouched, then all you are left with is printing money and raising government spending.

A social economy

However, there is an alternative. Once the current lockdowns end, what is needed to revive output, investment and employment is something like a “war economy” or, more accurately, a “social economy”. The slump can only be reversed with massive government investment, public ownership of strategic sectors and state direction of the productive sectors of the economy. Andrew Bossie and J W Mason outline the experience of the public sector role in the wartime US economy. They show that all sorts of loan guarantees, tax incentives and other measures were initially offered by the Franklin Roosevelt administration to the capitalist sector. But it soon became clear that the capitalists could not do the job of delivering on the war effort because they would not invest or boost capacity without profit guarantees. Direct public investment took over and government-ordered direction was imposed. Bossie and Mason find that federal spending rose from about 8-10 percent of GDP during the 1930s to an average of around 40 percent of GDP from 1942 to 1945. Most significantly, contract spending on goods and services accounted for 23 percent of GDP on average during the war. Currently in most capitalist economies public sector investment is about 3 percent of GDP, while capitalist sector investment is 15 percent or more. In the war that ratio was reversed.27

What happened was a massive rise in government investment and spending. In 1940, private sector investment was still below the level of 1929 and actually fell further during the war. So the state sector took over nearly all investment, as resources (value) were diverted to the production of arms and other security measures in a war economy. John Maynard Keynes himself said that the war economy demonstrated, “it is, it seems, politically impossible for a capitalistic democracy to organise expenditure on the scale necessary to make the grand experiments which would prove my case—except in war conditions”.28

The war economy of 1941-5 did not stimulate the private sector; it replaced the “free market” and investment for profit. To organise the war economy and to ensure that it produced the goods needed for war, the Roosevelt government spawned an array of mobilisation agencies that not only often purchased goods but closely directed their manufacture and heavily influenced the operation of private companies and whole industries. Bossie and Mason conclude that:

The more—and faster—the economy needs to change, the more planning it needs. More than at any other period in US history, the wartime economy was a planned economy. The massive, rapid shift from civilian to military production required far more conscious direction than the normal process of economic growth. The national response to the coronavirus and the transition away from carbon will also require higher than normal degrees of economic planning by government.29

Another leg in the Long Depression

In the absence of this, far from a quick snap back in the world capitalist economy when the lockdowns end, the prospect is for another leg in the “Long Depression”, characterised by low output, investment and income growth. After the Great Recession there was no return to previous trend growth whatsoever. When growth resumed, it was at a slower rate than before. Since 2009, US per capita GDP annual growth has averaged 1.6 percent. At the end of 2019, per capita GDP was 13 percent below trend growth prior to 2008. At the end of the 2008-9 recession, it was 9 percent below trend. So, in spite of a decade-long expansion, the US economy has fallen further below trend since the Great Recession ended. The gap is now equal to a permanent loss of income of $10,200 per person. Today Goldman Sachs is forecasting a drop in per capita GDP that will wipe out all the “gains” of the past ten years. The massive spending by the US Congress and the huge Federal Reserve monetary stimulus won’t stop this deep slump or even get the US economy back to its previous (low) trend.

An economic recession can lead to “scarring”—long-lasting damage to the economy. IMF economists have noted that after recessions there is not always a V-shaped recovery. Indeed, it has been often the case that the previous growth trend is never re-established. Using updated data from 1974 to 2012, they found that irreparable damage to output is not limited to financial and political crises. All types of recessions, on average, tend to lead to permanent output losses. That does not just apply to a single economy; it also impacts upon the gap between rich and poor economies: “Poor countries suffer deeper and more frequent recessions and crises, each time suffering permanent output losses and losing ground”.30

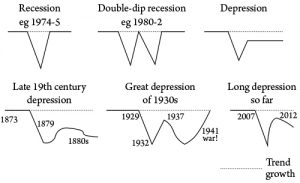

Their paper complements my view of the difference between “classic” recessions and depressions.31 In depressions, the recovery after a slump takes the form, not of a V-shape, but more of a reversed square root shape, which sets an economy on a new and lower trajectory (figure 7).

Figure 7: Schematic representation of the shape of various recessions

Perhaps the depth and reach of this pandemic slump will create conditions where capital values are so devalued by bankruptcies, closures and layoffs that weaker capitalist companies will be liquidated and more successful, technologically advanced companies will take over in an environment of higher profitability. This would be the classic cycle of boom, slump and boom that Marxist theory suggests. However, the past ten years have been more similar to the period of crisis in the late 19th century. Now it seems that any recovery from the pandemic slump will be drawn out and also deliver an expansion that is below the previous trend for years to come. It will be another leg in the long depression we have experienced for the past ten years.

The story of the Great Depression of the 1930s and the war that followed shows us that once capitalism is in the grip of a long depression, there must be a grinding destruction of the capital accumulated in previous decades before a new era of expansion becomes possible. There is no policy that can avoid that and preserve the capitalist sector. If the required capital destruction does not happen this time, then the Long Depression that the world capitalist economy has suffered since the Great Recession could enter another decade. The major economies (let alone the so-called emerging economies) will struggle to come out of this slump unless the law of the market and of value is replaced by public ownership, investment and planning, utilising all the skills and resources of working people. This pandemic has shown that.

Michael Roberts is a Marxist economist who blogs at thenextrecession.wordpress.com. He is the author of The Great Recession: A Marxist View (Lulu, 2009) and The Long Depression: Marxism and the Global Crisis of Capitalism (Haymarket, 2016). He is also co-editor of World in Crisis: A Global Analysis of Marx’s Law of Profitability (Haymarket,2018) and Marx 200: A Review of Marx’s Economics (Lulu, 2020)

Notes

2 Georgieva, 2020.

3 Mulligan, 2002.

4 Roberts, 2016.

5 Brooks and others, 2020.

6 World Trade Organisation, 2020.

7 World Bank, 2020.

8 Rogoff, 2020b.

9 See Ali Jan, 2020; Roberts, 2018.

10 Kose and others, 2020.

11 ILO, 2020.

12 Quoted in Cohan, 2020.

13 Krugman, 2020.

14 Hyman Minsky argued that financial systems would tend to move from stability to fragility, resulting in a sudden collapse of financial asset prices. His work has influenced many “post-Keynesian” economists. See Roberts, 2019a.

15 As Marx wrote in a letter to his friend Louis Kugelmann in 1868, “every child knows a nation which ceased to work, I will not say for a year, but even for a few weeks, would perish”—Marx, 1988, p68.

16 Dillow, 2020.

17 Plender, 2020.

18 IMF, 2020.

19 Baines and Hager, 2020.

20 El-Erian, 2020.

21 Tooze, 2020.

22 Coppola, 2020.

23 For a Marxist critique of MMT, see Roberts, 2019b.

24 Pettis, 2019.

25 Roberts, 2012.

26 Guerrieri and others, 2020.

27 Bossie and Mason, 2020.

28 Cited in Renshaw, 1999.

29 Bossie and Mason, 2020.

30 Cerra and Saxena, 2018.

31 I discuss this in depth in Roberts, 2016.

References