The new decade started with the news of flooding in Jakarta, Indonesia that killed more than 60 people and displaced tens of thousands. Caused by extremely heavy rainfall, the effects of the floods were exacerbated by poor infrastructure and the ongoing sinking of the city due to groundwater extraction. Homes were inundated with filthy water; one mother described trying to raise her baby in an emergency shelter full of wet garbage: “My baby is not sleeping as the rain comes in and the wind comes in… It is disgusting here, but we are stuck”.1 The response of the ruling class is to move the capital city to Borneo, but this will provide little comfort to the poorest inhabitants of Jakarta.2 Disasters like this can bring into sharp relief all the existing relations of class exploitation and oppression within a society. They reveal that the human relationship with the natural environment under capitalism is already irrational and destructive, even in “normal” times.

People around the world are responding to these events already by trying to find safer places to live and we can expect to see greater numbers of refugees and migrants in future due to climate change. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has stated that “the greatest single impact of climate change might be on human migration”.3 This means there is an urgent need for socialists to consider how to respond. It is a complex issue that affects huge numbers of people on every continent on Earth. Therefore, this article will not discuss every example of people moving due to climate change in detail. Instead, the aim is to provide an overview of the scale of environmental migration, an explanation of the arguments around the ongoing conflict in Syria, which is sometimes discussed as an example of a climate war, and some suggestions as to how Marxists can approach the issue. Some accounts have supposed that there is a linear relationship between increased climate change and more conflict (and therefore more refugees) in places such as the Middle East and sub-Saharan Africa. However, this discussion will caution against some of these mechanistic interpretations, arguing that it is not inevitable that people will turn to violence in response to a warming world. The article concludes with some thoughts on the importance of raising anti-racist arguments in the environmental movement.

Unnatural disasters

People moving from one part of the world to another due to ecological breakdown is not new. Indeed, climatic changes thousands of years ago played a role in the development of agriculture and the establishment of settled societies and cities. The Irish Great Hunger in the 1840s saw one million deaths, and a further one million people leaving Ireland, many of them settling in Britain, the United States and Canada. Although the immediate cause was ecological—the failure of the potato harvest due to a fungal disease—the scale of the suffering was made immeasurably worse due to the actions of the British government.4 Karl Marx outlined in Capital how British colonial policies had laid the ground for the disaster in the first place by moulding Irish agriculture to the requirements of the colonial power: “For a century and a half England has indirectly exported the soil of Ireland”.5 Similarly, anyone who has read John Steinbeck’s classic The Grapes of Wrath will also be aware of the suffering experienced by Americans in the 1930s trying to escape the dustbowl and searching for work elsewhere.

Environmental migration will undoubtedly become more of a political issue in the coming decades. There are various estimates of how many climate-related refugees and migrants there will be. The most widely cited study suggests that around 200 million people will be displaced due to climate change by 2050, around a ten-fold increase on current rates, although the academic who came up with this figure admits it is only an estimate. Another study from academics at Cornell University talks about 2 billion climate refugees by 2100, a staggering figure that would amount to a fifth of the global population.6

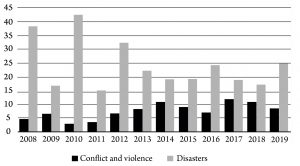

As figure 1 demonstrates, “disasters” have consistently been a bigger reason for internal displacement than conflict or violence in the past ten years. This category includes geophysical events such as earthquakes and volcanoes. But the vast majority of displacements of people are due to weather-related events such as storms, floods, fires and drought (table 1). It is these weather-related disasters that are likely to become more common with increased climate change. Warmer temperatures mean more moisture in the air. This is likely to contribute to “extreme precipitation events”, particularly in South East Asia. The risk of wildfires increases with warming, flooding is likely to become more common as sea levels rise and it is probable that tropical storms will be more frequent, intense and devastating, hitting coastal regions especially hard when combined with sea level rise.7

Figure 1: New displacements associated with conflict/violence and disasters in millions (2008-2019)

Source: Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, 2019; 2020.

Table 1: Causes of disaster-related internal displacement in 2019

|

Disaster type |

Number displaced |

|

|

Geophysical |

Earthquakes |

922,500 |

|

Volcanic eurptions |

24,500 |

|

|

Weather related |

Cyclones, hurricanes and typhoons |

11,900,000 |

|

Other storms |

1,100,000 |

|

|

Floods |

10,000,000 |

|

|

Wildfires |

528,500 |

|

|

Droughts |

276,700 |

|

|

Landslides |

65,800 |

|

|

Extreme temperatures |

24,500 |

|

Source: Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, 2020.

These will be unnatural disasters in several senses. Firstly, because dangerous climate change could have been avoided. As this journal has argued, the profit motives of a tiny proportion of the world’s population have been put before the survival of the many. Global capitalism has become dependent on fossil fuels and the industry and their supporters are powerful and influential. The science of climate change has been understood for several decades, yet governments have stuck to business as usual, failing to put in place the urgent measures needed to turn back from catastrophe and spreading doubt about the reality or seriousness of climate change.

Secondly, the effect that ecological breakdown has on people and the response of states is also shaped by the interests of capitalism. Indeed, the outcome of any disaster, whether climate-related or not, will be influenced by the type of society in which it takes place. For example, Cyclone Gorky in Bangladesh in 1991 left at least 138,000 people dead. The following year, Hurricane Andrew hit Florida and Louisiana. Despite being a stronger storm, the death count of 65 was much lower.8 The way in which social forces shape the outcomes of disasters (including the Covid-19 pandemic) has led many to conclude that the degree to which an event such as a storm becomes a disaster depends on how vulnerable the population is; there is no such thing as a “natural” disaster.9 Some scholars have also used the terminology of “hazards”, in recognition of the fact that facing extremes of environmental variation is an integral aspect of how societies relate to their surroundings. This also implies a longer-term perspective of how people understand and cope with risk rather than a focus only on a particular destructive event such as a fire or hurricane.10

Environmental hazards can force people from their homes, but the experience of being a refugee can itself make someone more vulnerable to the effects of climate change due to inadequate accommodation, resources or social support networks. Areesha camp in northern Syria has flooded several times, with heavy rainfall destroying people’s tented accommodation.11 This has also been illustrated recently by Covid-19—refugees and their supporters fear the consequences of an outbreak in refugee camps where people will not be able to self-isolate and may not even have access to adequate washing facilities.12

One of the most striking illustrations of the effects of a warming climate on human migration is the plight of people on low-lying islands. For example, Kiribati in the Pacific Ocean could become entirely uninhabitable in a matter of decades. Rising sea levels and storm surges are combining with biodiversity loss, warmer temperatures and the contamination of freshwater supplies with saltwater. Its government has already purchased an area of land in Fiji of over 6,000 acres to rehome the population and is encouraging people to leave.13

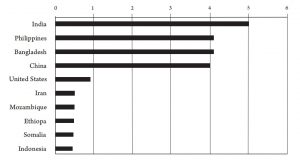

India and the Philippines currently account for huge numbers of displacements, with 5 million people displaced in India in 2019, mostly due to monsoons and cyclones (figure 2).14 Riverbank erosion, which is predicted to worsen in the coming years, displaced thousands of people in Bangladesh in 2018. The country has one of the highest rates of displacement due to flooding in the world, with 1.8 million displaced people in any given year. Many of them are expected to move to the capital, Dhaka.15 In Southern Africa, the unusually powerful Cyclone Idai displaced hundreds of thousands of people in 2019, mostly in Mozambique.

Figure 2: Ten countries with most new displacements associated with disasters in 2019 (numbers of people displaced in millions)

Source: Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, 2020.

A series of reports in the Guardian have argued that climate change has played a role in the recent movements of people from Central to North America, forcing them to join the “migrant caravans” trying to cross the border into the US. Changing weather and drought are proving devastating for people who rely on their crops to have enough food to eat, with some farmers reporting that there has been no maize crop at all in some years.16 As in other zones of mass displacement around the world, this is likely to be an example of mixed migration, with people trying to cross the border due to conflict or repression mixing with those forced to move due to the collapse of local food markets. In many cases the drought is likely to be the final factor in causing people to move who have already faced the crushing impact of trade deals such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which undermined domestic agriculture in Mexico.17

In the Western hemisphere it is the US itself that consistently experiences the most internal displacement due to disasters (at least in terms of absolute numbers of people). In 2018, more than 1.2 million people were forced to leave their homes. This included more than 350,000 people in California, which experienced the most destructive wildfires in its history in that year.18 The devastating fires in Australia over the past year and the effects of storms and fires in the US demonstrate that even the so-called “high-income” countries are ill-equipped to cope with climate change.

Although it seems clear from these examples that climate change will have an effect on migration, it has been fiendishly difficult to try to find an overall pattern at a global scale. In 2017, the New York Times published a world map showing forcible displacements of people and temperature change alongside an article suggesting that there is some correlation between the two.19 However, as we might expect, the map reveals many exceptions to the trend. There is a complex array of different factors involved. As we know, the issue is not generally one of high temperatures as such, but their effects in terms of oceanic warming or reduced or less predictable rainfall. Therefore, temperature change is only a proxy, and not an ideal one, for climate-related extreme weather events. This is before we even start to look at the social reasons why some populations are more vulnerable and why some people choose to move while others stay where they are.

The Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre treats “conflict” and “disasters” as two separate causes. However, commentators are increasingly concerned that climate change might lead to conflict. The United Nations has stated that: “While not in themselves causes of refugee movements, climate, environmental degradation and natural disasters increasingly interact with the drivers of refugee movements”.20 In particular, the 2003 conflict in Darfur marked a turning point in official interest in the link between climate and conflict. In the Darfur conflict, which followed a severe and long-lasting drought, hundreds of thousands of people died and more than 2 million were internally displaced.21 Although accepting that the causes of the war were extremely complex, Jonathan Neale points to the role of climate change:

Abrupt climate change will create famine and refugees on a massive scale. It will also mean war. Change the balance of economic and geographical power, and governments will use military might to grab it back. If you want to see that future, look at Darfur.22

More recently, some have looked at the role of drought as one factor in the Syrian civil war. To understand how environmental change, neoliberalism and political power struggles have fuelled the conflict it is necessary to understand a little about Syria’s recent history.

Revolution and war in Syria

Colonialism had a divisive influence in Syria. Established by the Sykes-Picot agreement in 1916, during the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, it was a French colony until 1946. The French Mandate authorities divided up Syria (and Lebanon) along religious lines, establishing distinct statelets for the Alawite and Druze populations and dividing the rest of the country into two, with one state centred on Damascus and the other centred on Aleppo. However, as Anne Alexander and Jad Bouharoun have described, there were repeated revolts against French rule in the 1920s that were often able to unite people across sectarian divisions.23

After independence, Syria was a deeply unequal state; a tiny elite dominated land ownership and played a disproportionate role in political life while landless sharecroppers made up two-thirds of the peasantry. Yet by the second half of the 20th century, a new political class had come to prominence. The Ba’ath Party, led by Hafez al-Assad, rose to power in a coup in 1970. The party drew on the new middle class for part of its support.24 In 2000, Bashar al-Assad succeeded his father as president. Assad junior instituted a series of neoliberal measures that resulted in the liberalisation of trade, cuts and privatisation of sections of the welfare state and the abolition of rent controls. Overall, real wages declined and poverty and youth unemployment increased.

Perhaps most significantly for this discussion of climate refugees, these measures also affected agriculture. Land in arid regions was privatised and used for growing wheat and cotton commercially, but the effect of this, combined with mismanaged irrigation, was a long-term decline in freshwater supplies, making rural Syrians particularly vulnerable to drought.25 Syrian oil production peaked and started to decline in the 1990s, leading to a cut in fuel subsidies in 2008. This had further consequences for water supply and agriculture because fuel is needed to work water pumps.26

Also, beginning in the 1970s, rainfall from the Mediterranean became less predictable, leading to what are thought to be the driest conditions in Syria in 900 years. Between 2006 and 2010 the drought was particularly intense and livestock farming and harvests of wheat and barley collapsed.27 As Alexander and Bouharoun explain:

The social consequences of the combination of natural disaster with neoliberal agricultural policies were profound. Up to 3 million small-scale farmers and herders lost their livelihood and were driven off their lands and into poverty.

Many of them migrated to the south and west of the country, to places such as Deraa in the south or to the periphery of Damascus. This fed into a growing population in these cities, which faced both poverty and political repression at a time when the Assad government and its cronies were continuing to enrich themselves, investing in golf courses and luxury apartments.28

The Syrian Revolution that began in March 2011 has been discussed at greater length elsewhere in this journal than is possible here.29 Starting as a popular uprising inspired by the revolts in Egypt, Tunisia and elsewhere that became known as the Arab Spring, the revolution drew its support from the urban peripheries, including among those who had migrated from rural areas. So, the anger among farmers who had lost their livelihoods may have played a role. Deraa, mentioned above, was one of the centres of the revolt after a group of teenagers were arrested and tortured for writing “the people want to overthrow the regime” on a wall, which sparked militant protests in the city.30 At its high point, the revolution brought up to one million people onto the streets and saw the beginnings of alternative modes of government in the form of revolutionary councils. In Idlib and Aleppo it inflicted military defeats, and at times it looked close to toppling the government.31 However, the Assad regime’s forces were able to contain the movement, responding to the protests with brutal force and using artillery, barrel bombs and chlorine gas against civilian populations.32 Both sides in the ensuing civil war gained the support of regional and international powers. The Lebanese Shia militia Hizbollah, the Iranian Revolutionary Guards and the Russian state all backed Assad at various points in the conflict, while armed anti-government forces attracted funding from the Gulf states, Turkey and the US. Islamist rebels such as Jabhat al-Nusra, whose politics are far from those of the initial uprising, became more prominent among the anti-government forces.33 The actions of the state and the intervention of the various regional actors rapidly polarised the war along sectarian lines, although this must be understood in the context of sectarian divisions that were already present in the Ba’athist state.34

Around 500,000 people have died in the Syrian civil war.35 Many more have been forced to move, with 6.6 million internally displaced and 5.6 million leaving Syria, making this the biggest movement of refugees in recent times. Although some Syrian refugees have come to Europe, the vast majority of those displaced by the fighting have remained within the region: there are 3.6 million Syrian refugees in Turkey, around one million in Lebanon, 655,000 in Jordan, 246,00 in Iraq and at least 126,000 in Egypt.36 Some of these people will have migrated twice—moving into urban areas during the period of drought and then fleeing again several years later as the war intensified.

Is Syria a source of climate refugees?

Naomi Klein argues that the impact of the drought on rural to urban migration was significant for the uprising and subsequent war and refugee crisis in Syria. She notes that the revolution started in areas that had experienced migration into cities:

Deraa is where Syria’s deepest drought on record brought huge numbers of displaced farmers in the years leading up to the outbreak of Syria’s civil war, and it is where the Syrian uprising broke out in 2011. Drought was not the only factor in bringing tensions to a head. But the fact that 1.5 million people were internally displaced in Syria as a result of the drought clearly played a role.37

Klein, drawing on the theories of Israeli architect Eyal Weizman, refers to the aridity line in trying to find a correlation between climate change and conflict. This line designates areas where the average rainfall is 200 millimetres per year. Populations on the aridity line will be able to grow cereal crops without irrigation but will be at risk of drought and desertification. A map in one of Klein’s articles shows how the aridity line circles the Sahara Desert and extends eastwards through the Middle East and into Afghanistan, Pakistan and the west of India. She intriguingly shows how many of the sites of Western drone strikes—taken as a proxy for conflict—including in Mali, Libya, Gaza, Yemen, Somalia, Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iraq, were on or close to the aridity line. Klein concludes: “Just as bombs follow oil, and drones follow drought, so boats follow both: boats filled with refugees fleeing homes on the aridity line ravaged by war and drought”.38

One advantage of accounts of climate wars is that they are a corrective to the type of analysis that blames religion and ethnicity for outbreaks of violence. The Assad regime and their supporters have tried to paint the Syrian uprising as a “terrorist conspiracy”.39 By contrast, those who point to the drought as a factor in the conflict make clear that Syrians had a genuine grievance against their government’s policies. It is a materialist explanation, rather than one that sees conflict as arising due to the invasion of “jihadist” ideas.

However, there are reasons to be cautious about the suggestion that conflict is bound to follow climate change. Some progressive thinkers are concerned that climate change is being “securitised” as it is adopted by militaries and linked to issues of conflict and terrorism.40 Indeed, the US Department of Defense has taken more of an interest in climate change in recent years. Its 2014 Climate Change Adaptation Roadmap made its concerns explicit:

The impacts of climate change may cause instability in other countries by impairing access to food and water, damaging infrastructure, spreading disease, uprooting and displacing large numbers of people, compelling mass migration, interrupting commercial activity, or restricting electricity availability. These developments could undermine already-fragile governments that are unable to respond effectively or challenge currently stable governments, as well as increasing competition and tension between countries vying for limited resources. These gaps in governance can create an avenue for extremist ideologies and conditions that foster terrorism.41

For the US military establishment, the prospect of “societal breakdown” and conflict in a warming world is a threat that calls for new strategies of counter-insurgency.42 This continued during Donald Trump’s presidency, despite his denial of climate change. As John Sinha argues, even far-right figures in the mould of Trump might switch their strategy in the future from climate denial to imposing their own solutions to climate change in the form of more walls and barbed wire.43

When employed by organisations such as the UN, arguments about climate refugees can be used as justification for intervention by international development bodies and non-governmental organisations (NGOs). This can obscure discussion of the often detrimental consequences of Western intervention in the first place, whether in the form of military intervention or structural adjustment policies mandated by the World Bank and International Monetary Fund.44 In the case of Syria, Jan Selby and Mike Hulme have criticised the securitised narrative around climate refugees, arguing that trying to link climate change to conflict is “sensationalist”.45 Similarly, some argue that the term “climate migrant” is misleading or even dangerous due to its association with alarmist calls for greater migration controls and because it conceals the economic and social reasons for migration.46

Betsy Hartmann adds that the narrative of a security threat from climate refugees builds on problematic ideas originating with colonialism such as the “degradation narrative”.47 This assumes that people in the Global South degrade the natural environment due to their farming and herding practices, causing soil depletion and desertification in response to the pressures of a growing population, which in turn causes migration. This interpretation overlooks other potential causes of damage to the environment, including those related to agricultural reform and the influence of extractive industries. Hartmann argues that the narrative of degradation has little basis in fact. It draws on racist “fears and stereotypes of the dark-skinned, over-breeding, dangerous poor” and old arguments that environmental problems are really caused by overpopulation.48

In the case of Syria it is difficult to tease out the specific influence of climate change, especially as the environmental factor was a drought that took place over a long time period, rather than a sudden onset event such as a flood or storm that caused people to migrate. For authors such as Christiane Fröhlich, climate change is certainly a real concern, but its effects cannot be understood without also addressing the economic and political context, including the neoliberal and authoritarian agricultural policies of the Syrian government.49

It is one thing to say that climate change will lead to hardship, another to argue further that this will result in conflict. Some have argued that such an analysis grossly oversimplifies the situation by playing down the role of political factors in conflict situations.50 Political rivalries certainly did play a role in the case of Syria. Our analysis of the roots of conflict and displacement should not absolve political forces such as the Assad regime of blame.51

Hartmann provides several examples from research in Africa that challenge the assumption that extreme weather might lead to conflict. For example, research in northern Kenya has shown that drought actually led to less violence among herders rather than more. This is because herders establish their own systems to negotiate and govern access to water and are not inclined to start fights during droughts. Where conflict does occur, Hartmann concludes that this is more often due to the detrimental effects of outside intervention, it is a sign that “local resource users themselves have been made powerless and that their negotiating system has been paralysed, either by external agencies or local elites”.52

However, Hartmann seems too dismissive of the very notion of a climate refugee. She suggests that accounts of climate refugees “depoliticise the causes of displacement” as they place the blame on an external environmental factor.53 Yet climate change is very much a political issue. In Latin America, South Asia, Syria and many other places, people have been made vulnerable to the effects of extreme weather by neoliberal agricultural and trade policies. A more radical analysis could address how the global expansion of fossil fuel extraction that is ultimately the cause of climate change is also a feature of the same aggressive drive towards neoliberalism. Research by Lucia Pradella and Rossana Cillo on Libya has outlined how oil extraction and the system of detention and militarised borders are interlinked. From 2014, Italy’s main oil and gas company, ENI (Ente Nazionale Idrocarburi), collaborated with the Al-Ammu and Brigade 48 militias in Libya in order to maintain its supplies. The resulting drain of Libya’s resources led to further impoverishment within the country and there was an increase in migrants being pushed towards Europe. These authors argue that the migrants acted as a reserve army of labour that was easily exploited in an Italian agricultural industry that also benefitted from energy imports from Libya. They point to a link between poverty and environmental degradation in the Global South and in the North.54

Andreas Malm is more sympathetic to the argument that drought played a role in Syria. However, he cautions that temperature rise will not act as a cause of unrest in a linear manner. This will depend on the levels of anger and discontent already present within a society.55 Responses to climate change might also involve people revolting against those at the top of society or even the kind of revolutionary upheavals seen in Syria. The degree of political organisation our side can draw on will undoubtedly play a role in determining these outcomes. The possibility of revolution has been little understood in much of the mainstream discussion of this topic. For instance, Selby and Hulme state that, in the case of rural to urban migrants in Syria, there is “no evidence that any of the early unrest was directed against these migrants”.56 But why should there have been? The Syrian civil war began as a revolution that, at least temporarily, united migrants from rural areas and urban dwellers against their government. Selby and Hulme seem to assume that it was a case of stressed poor people attacking each other.

There is strong evidence that climate change will lead to more extreme weather events and more movements of people. However, we should also accept that it is not inevitable that events such as droughts will be followed by conflict and consequently by flights of refugees. This downplays people’s own agency in coping with and adapting to the ecological circumstances in which they find themselves.

Climate justice and solidarity

Climate refugees are already being discussed as part of a growing movement around climate change. In recent years increasingly alarming reports about the extent and rapidity of climate and ecological breakdown have been met with mass, radical protest. In late September 2019 an estimated 7 million people around the world took part in some form of climate protest after the global movement of school strikers inspired by Greta Thunberg called for adults to walk out of work in solidarity.57 In Britain, this was almost certainly the biggest ever protest over the issue of climate change by working class people, organised in their unions as workers. It is a global movement. School strikes took place in 161 countries, with big protests in India, the Philippines, South Africa, Kenya, Brazil, Mexico, Australia, the US and many other places.58

Having declared a state of emergency in autumn 2018, Extinction Rebellion (XR) has embarked on a mass campaign of civil disobedience, blocking streets in Central London in two huge rebellions as well as organising numerous other actions around Britain and elsewhere. XR has been incredibly impressive and successful in mobilising people scared and angry about our government’s lack of action on climate change (and ecology more broadly) and in putting these issues on the media agenda. Alex Callinicos is right to say that there is a need for humility when socialists engage with this movement.59

However, more than two years on, there are intense debates within the movement, many of which concern issues of race and social justice. In 2019, a high-profile open letter to XR made several criticisms of the group, including that, by encouraging activists to get arrested as a central tactic, XR lacked awareness of black people’s experiences of police violence. The letter made the key point that the rhetoric of much of the environmental movement assumes that ecological breakdown is a looming threat that will happen in the future. For many people, especially in the Global South, ecological violence is already a present day reality.60

The founders of XR in the UK set out to make the organisation as broad as possible. Although they are not resistant to talking about social justice as such, they also wanted to make the group appealing to conservatives in an effort to recruit from beyond the left and those already involved in political activism.61 According to their line of reasoning, the struggle against climate change will be so monumental that it will need a movement on an unprecedented scale, and therefore it should include as many people as possible—XR has sometimes talked in terms of 3.5 percent of the population being needed to make the necessary change. Some therefore suggest that talking about race might alienate those with more conservative views. XR founder Roger Hallam has said that “identity politics” has significant drawbacks, in that “it can’t appeal to everyone”.62

In the US, XR has split over such issues. Although XR US had the need to prioritise “black people, indigenous people, people of color and poor communities” embedded within its demands, a group called XR America split away from XR US, removed this demand and replaced it with wording that talked about “one people, one planet, one future”.63 According to XR America founder Jonathan Logan, climate change is just too urgent to take on social justice demands:

If we don’t solve climate change, black lives don’t matter. If we don’t solve climate change now, LGBT+ people don’t matter. If we don’t solve climate change right now, all of us together in one big group, the #MeToo movement doesn’t matter… I can’t say it hard enough. We don’t have time to argue about social justice.64

Prominent XR member Rupert Read has written in the past that environmentalists should be in favour of halting mass immigration and that this would put us on the side of “working-class Britons”.65 However, aside from the obvious point that plenty of working class British people are from migrant backgrounds, this assumes that people’s ideas are static. Experience shows that people’s ideas change, especially when they are engaged with others in mass movements. Read’s position also ignores research that suggests that people from black and ethnic minority backgrounds are more likely to be concerned about environmental issues than white people.66 Playing down discussions of race in order to appeal to an (imagined) white conservative milieu ignores a big potential audience among people who are being drawn into political activity by their anger about racism.

The other reason to build an internationalist and anti-racist movement is that it is the best way to fight climate change. As Klein has argued, the “othering” or dehumanisation of many of the people most affected is, in part, what has allowed climate change to go on for so long in the first place. Environmental racism has allowed governments in the Global North to downplay the effect of their inaction and to treat parts of the world such as the Niger Delta as sacrifice zones for the extraction of fossil fuels. Klein talks about the Global South but also mentions rural poverty in the US, referring to the neglect of communities affected by mountain-top removal coal mining: “If you are a ‘hillbilly’, who cares about your hills?”67

However, it should be emphasised that environmentalists who want to limit discussions of social justice are in the minority, both in the US and Britain. There are ongoing discussions in XR groups across Britain about adopting a “fourth demand” in order to make climate justice a more explicit part of what the group stands for (the existing three demands of XR are “tell the truth”, “act now” and “beyond politics”). A recent online poll of XR supporters found that 77 percent of respondents were in favour of a fourth demand, with 60 percent strongly in favour. Rather than seeing these demands as unattractive, more people than not thought that such a demand would be popular with the public and most said that it would make them more contented to continue to be involved with XR.68

Debates about climate justice are refracted and magnified in discussions of climate refugees. It is tempting for those who say we do not have time to talk about social justice to also treat climate-related migration as a problem that must be solved by first addressing climate change. For others, discussions about migration are a distraction from these efforts. According to Read, one of the most effective and humane ways to limit migration is to tackle climate change, therefore removing a push factor that causes people to move.69 From a more sympathetic perspective, but with an argument that leads in the same direction, Lauren Markham argues in The Guardian that:

Migration is a natural human phenomenon and, many argue, should be a fundamental right, but forced migration—being run out of home against one’s will and with threat to one’s life—is not natural at all… If we want people to be able to stay in their homes, we have to tackle the issue of our changing global climate, and we have to do it fast.70

Few would argue in favour of people being forced from their homes. However, tackling climate change cannot be the end of the discussion on climate refugees. This again treats climate change as a calamity that will face us in the future. It ignores the role of colonial policies of the past and neoliberal capitalism in creating the conditions for both climate change and migration. As this article has shown, extreme weather is already displacing millions of people. Moreover, states around the world are already erecting borders and trying to prevent people from fleeing ecological breakdown that those selfsame states have played a role in causing.

Socialists need, therefore, to have a view on climate refugees. We should put anti-racist arguments against borders and controls on migration. Borders have not always existed but arose with the modern state and the colonial carve up of the world in the 19th and 20th centuries (including in Syria). They cause immediate suffering to those trying to cross them. As Klein puts it: “The same capacity for dehumanising the other that justified the bombs and drones is now being trained on these migrants, casting their need for security as a threat to ours, their desperate flight as some sort of invading army”.71 National borders also foster racism, creating a division between those who are included within the nation-state and those derided as aliens or outsiders. This divides people against each other and ultimately serves the interests of capitalists in exploiting and oppressing ordinary people.72 Socialists should try to convince others of these arguments, including those who see nation-states and borders as necessary or inevitable. It is hardly surprising that people think this way; in Britain all the mainstream political parties and most of the media argue for some kind of controls on migration. However, if any of the predictions of the numbers of climate refugees are accurate it will become more and more difficult to justify controls on migration in the decades to come. Bringing anti-racist ideas into the environmental movement provides an opportunity to discuss these ideas with a newly radicalised group of people who have been drawn into the climate movement.

We can also put arguments about migration that acknowledge the agency of the refugees and migrants themselves. We can point to the many examples of the contributions migrants and refugees make in the societies that they move to as well as the positive role that migration can play in the lives of migrants themselves. In Britain, migrants have staffed public services, including the NHS. They have organised in some key trade union struggles, from the strikes of Asian workers in the 1970s to the fight for decent pay for cleaners in more recent times. They have sometimes brought militant traditions with them. Refugees from Syria who were part of the revolution have been part of anti-racist protests in Greece, for example.73

Our solidarity with refugees should not be conditional on them “making a contribution”. All migrants and refugees should be welcome as a point of principle. Nevertheless, it is important to point to some positive examples of migrants playing an active role in working class movements. This is because there is a tendency for some environmentalists to treat the displacement of refugees as just another addition to the long list of terrible things that will happen if we do not address climate change. It is almost as if the “threat” of refugees is being used to try to force our governments to act on climate change. This is why Minnie Rahman of the Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants says that “the way forward is to ensure that any organising around climate migration has to be done in a way that does not treat movement as a threat”.74 The securitisation discourse described above likewise treats refugees as a potential danger for national security. On this point Selby and Hulme are right to say that there are strong enough reasons for acting on climate change already without trying to turn it into a security issue.75

Some participants in discussions around climate refugees have been tempted to use metaphors of natural disasters to refer to the refugees themselves, for instance, referring to “waves” or “floods” of people. Anti-racists should avoid such dehumanising language.76

A legal status for climate refugees?

Where people cross borders in an attempt to escape disasters, they will not be recognised as refugees by international law.77 The 1951 Refugee Convention states that a refugee is someone who, due to a “a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality, and is unable to or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country”. Written in the aftermath of the Second World War, this convention was shaped by the Cold War agenda and intended to attract defectors from the Soviet bloc towards the West. By defining refugees solely in terms of persecution, it has always excluded people moving due to ecological degeneration, economic collapse or the effects of new infrastructure such as mineral extraction, dams or plantations.78 Although people who move within a state do receive some support from the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), they are not legally defined as refugees.

So, should the definition of a refugee be expanded? There are arguments from migrant and refugee advocates on both sides. Michael Doyle of Columbia University points out that people escaping the effects of climate change are migrating against their will. They are just as much “forcibly displaced” as those escaping persecution:

If your farm has been dried to a crisp or your home has been inundated with water and you’re fleeing for your life, you’re not much different from any other refugee… The problem is that other refugees fleeing war qualify for that status, while you don’t.79

Avidan Kent and Simon Behrman further argue that climate refugees are faced with structural violence in the form of climate change, which might cause suffering comparable to the interpersonal violence feared by those escaping persecution.80

However, some point out that the reasons for leaving somewhere are complex and interrelated, and so it will be very difficult for people to prove in practice that climate change was a factor and therefore attain the status of a climate refugee. Richer countries are, unsurprisingly, unwilling to extend the definition of a refugee and the UNHCR is also resistant to the idea because it is already stretched and lacks the financial resources to cope with the huge rise in refugee numbers that would potentially result.81

The UN also points out that people fleeing from the effects of climate change will often stay within the same country. If drought, tropical storms and sea level rise cause more people to leave their homes in the coming decades, we might expect to see more people moving from rural to urban areas within the same country, or leaving coastal areas to head inland.82 Farmers in rural Nigeria affected by drought, for example, might lack the means or the inclination to travel to Europe, but may be able to move to a town or city. In many cases the poorest people will be “trapped” without the resources to migrate to another country, even if they want to.83 In this respect they differ from those escaping political persecution who may need to cross borders and cannot turn to their own state for support.

However, it is worth remembering that the vast majority of people who are displaced—for any reason—tend to move within a state (58 percent of forcibly displaced people) or to travel to a neighbouring state (a further 80 percent), so the existing legal protection is already inadequate. At present, the three countries that host the most refugees are Turkey, Pakistan and Uganda. With the exception of Germany, all of the world’s top eight refugee hosting countries share a border with a country of refugee origin.84 There has never been a huge exodus of people heading from the South to the North—at least not yet. If climate change makes large parts of the globe completely uninhabitable then there is likely to be a rerouting of global flows of refugees. However, even then this is unlikely to be a straightforward case of people leaving the Global South and heading to the Global North en masse.85

An end to controls on migration in their entirety would make debates about the legal distinction between refugees and migrants irrelevant. There would no longer be any need to justify moving from one part of the world to another. It could be accepted that everyone who moves does so for a number of reasons, including reasons to leave one place and the attractions of another. Kent and Behrman make this argument in their book on the legal aspects of climate and migration. However, they also make a compelling argument that, in the here and now, people crossing borders due to climate change should be defined as refugees. At least then their legal status would qualify them for more protection. In response to those who argue that talk of climate refugees deflects attention from solving climate change in the first place, these authors point out that the term “climate refugees” is actually more political than other terms such as “climate-induced migration”. Using the term “refugee” implies that someone is to blame, in this case the fossil fuel industry and the states that back it.86

Conclusion

In a welcome development, there have been some initial attempts to bring together anti-racist and environmental struggles over the past few years. The Campaign against Climate Change (CaCC) held a one-day conference in February 2017 with speakers from trade unions as well as anti-racist and environmental organisations.87 As part of XR’s first rebellion event in spring 2019, Stand up to Racism (SUTR), organised a rally with trade union banners and anti-racist speeches and some XR groups have incorporated an inflatable boat at their events in order to symbolise the issue of climate refugees. CaCC and others supported SUTR’s annual march in 2020 in order to make a clear link between climate change and refugees (although the demonstration unfortunately had to be turned into an online event due to the Covid-19 pandemic). A group called Global Justice Bloc (formerly Global Justice Rebellion) played a significant role during the 2019 and 2020 XR rebellions. In September 2020 they led a march from Parliament Square, where XR supporters had gathered, to the Home Office with the slogan “Climate Justice is Migrant Justice”. Protestors sat down and blocked the road and heard from a range of speakers on different aspects of climate justice. The group describes itself as anti-capitalist as well as anti-racist and anti-imperialist.88 Activists from the Global South have spoken out at climate events including a group of African women refugees at XR’s blockade of the BBC in December 2018, and an Ecuadorean striker from the PCS civil service union spoke on a picket line at the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy on 20 September 2019. The SUTR banner and placards and demands to welcome climate refugees have also been a regular and popular feature on school climate strikes. There are undoubtedly other examples like this. These modest initiatives show that there is much potential to link anti-racist arguments around refugees with the broader demands of the climate movement.

This article has argued that the world is already seeing the effects of climate and ecological breakdown in the form of disasters such as floods, fires and hurricanes. We know that these will lead to displacements of people—they already do—and they are likely to get worse in future. However, the effects of any disaster will be shaped by the social, political and economic context in which it happens. As Neale concludes in his discussion of Darfur, the tragedy was not a “simple climate change disaster”, but a process that must be seen in the context of competition rooted in the capitalist drive for profit on a global scale.89 The root cause of climate change is a global system based on profit. People are already feeling the catastrophic effects, and the worst affected tend to be the least responsible. However, this article has tried to put an account of climate refugees that recognises the agency of refugees themselves, rather than taking a liberal view that treats them as either passive victims or objects of charity. Climate change is a problem to be solved; people moving from one part of the world to another is not.

Camilla Royle teaches at King’s College London and is the author of A Rebel’s Guide to Engels (Bookmarks, 2020).

Notes

1 Associated Press, 2020. Thanks to Majed Akhter, Simon Behrman, Erica Borg, Alex Callinicos, Diego Macias Woitrin, Phil Marfleet, John Narayan and Lucia Pradella for their generous comments on this article in draft. The views expressed here are my own.

2 Varagur, 2020.

3 See Brown, 2008, p11.

4 Newsinger, 2006, pp34-38.

5 Marx, 1976, p860.

6 Brown, 2008, p10; Friedlander, 2017.

7 Berlemann and Steinhardt, 2017.

8 Brown, 2008, pp17-18. Sometimes measures of financial loss are used instead of death counts, which perversely implies that disasters are more damaging if they affect rich people—Mustafa, 2009.

9 See Pelling, 2001, for an overview of theoretical approaches to “natural disasters” and Choonara, 2020, on Covid-19.

10 Mustafa, 2009.

11 Save the Children, 2019.

12 KEERFA, 2020.

13 Ives, 2016.

14 Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, 2020, p48.

15 Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, 2019, pp34-35.

16 Milman, Holden and Agren, 2018; Markham, 2019.

17 Weisbrot, 2014.

18 Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, 2019, pp42-43.

19 Benko, 2017.

20 United Nations, 2018, p2. The UN currently does not include environmental migrants within the legal definition of “refugees”, an issue that will be discussed further below.

21 Ban, 2007.

22 Neale, 2010.

23 Alexander and Bouharoun, 2016, pp2-4.

24 Alexander and Bouharoun, 2016, pp5-10.

25 Fröhlich, 2016.

26 Fröhlich, 2016, p42.

27 Malm, 2016.

28 Alexander and Bouharoun, 2016, pp11-12; Malm, 2016.

29 Maunder, 2012; Alexander, 2016; Naisse, 2016; Hearn and Dallal, 2019.

30 Alexander and Bouharoun,2016, p14.

31 Hearn and Dallal, 2019.

32 Alexander, 2016.

33 Alexander and Bouharoun, 2016, pp22-23.

34 Alexander, 2016.

35 Hearn and Dallal, 2019.

36 All figures from www.unhcr.org/uk/syria-emergency.html

37 Klein, 2016.

38 Klein, 2016. The association of conflict with arid regions seems somewhat speculative. The attack on Gaza in 2014, in the context of decades of Israeli occupation and Palestinian resistance, is one example that sits uneasily with the narrative of a climate change war (although water rights certainly play a role).

39 Alexander and Bouharoun, 2016.

40 Selby and Hulme, 2015.

41 Department of Defense, 2014, p4, quoted in Callinicos, 2019, emphasis added.

42 Malm, 2016.

43 Sinha, 2020.

44 Writing in this journal, Julie Hearn and Abdulsalam Dallal make a strong case that NGOs have also played a damaging role in the case of Syria—see Hearn and Dallal, 2019.

45 Selby and Hulme, 2015. They doubt that 1.5 million people were displaced due to the drought in Syria and find that it was closer to 250,000.

46 Goodfellow, 2020.

47 Hartmann, 2010.

48 Hartmann, 2010, p238.

49 Fröhlich, 2016, pp40-41.

50 On Darfur, see Butler, 2007.

51 Malm, 2016.

52 Witsenburg and Roba, 2007, quoted in Hartmann, 2010, p237.

53 Hartmann, 2010, p236.

54 Pradella and Cillo, in press.

55 Malm, 2016.

56 Selby and Hulme, 2015.

57 Marches took place on either 20 September or 27 September, depending on local arrangements.

58 Socialist Worker, 2019.

59 Callinicos, 2019.

60 Wretched of the Earth, 2019.

61 Taylor, 2020.

62 See Roger Hallam’s comments in Dembicki, 2020.

63 Dembicki, 2020.

64 Quoted in Dembicki, 2020. This quote is from before the dramatic recent re-emergence of Black Lives Matter protests in the US.

65 Read, 2014.

66 Dembicki, 2020.

67 Klein, 2016.

68 The poll was initiated by Global Justice Rebellion and shared on their Facebook page on 2 July 2020. Go to https://bit.ly/34HwxDF

69 Read, 2014.

70 Markham, 2019.

71 Klein, 2016. One of the demands in the Wretched of the Earth’s open letter is also for an end to the hostile environment.

72 Marfleet, 2016.

73 Constantinou, 2016.

74 Goodfellow, 2020.

75 Selby and Hulme, 2015.

76 Markham, 2019.

77 Benko, 2017.

78 Thanks to Phil Marfleet for this point.

79 Quoted in Markham, 2019.

80 Kent and Behrman, 2018, p56.

81 Brown, 2008, pp13-15.

82 Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, 2019.

83 Brown, 2008, p22. Kent and Behrman, 2018, pp4-5.

85 Brown, 2008, p9.

86 Kent and Behrman, 2018, pp44-59. These authors point out that the definition of a refugee has in practice been extended to include other types of forced migrants not included in the 1951 convention and so it could in principle be further extended.

89 Neale, 2008, p233.