The ultimate outcome of the Russian invasion of Ukraine remained uncertain as International Socialism went to press. However, the brutality of the offensive was beyond doubt. This was epitomised by the siege of Mariupol, where shelling and airstrikes were said by Ukrainian officials to have killed thousands. A theatre in which 1,300 civilians were sheltering was struck, along with an art school housing another 400. Across Ukraine, although the number of deaths remains unclear, the United Nations has announced that ten million people, a quarter of the population, have been displaced.

If the plan by the Russian military was rapidly to crush resistance and topple the government in Kiev, it was unsuccessful. At the time of writing, almost a month into the offensive, the Russian army had suffered an estimated 7,000 or more casualties. There were reports of young, bewildered troops, some conscripts, wondering exactly what they were doing in Ukraine. Yet, as the offensive stalled, there were also fears that the Russian military would deploy increasingly destructive methods, as it had in previous conflicts in Chechnya and in Syria.

Among the radical left, the response to the invasion has been contested. One temptation has been to collapse into “campism”, a Cold War term applied to those who painted any state that clashed with the United States as progressive. This is the approach of the US-based Marxist periodical Monthly Review, whose April editorial refers to the invasion as the “Russian entry into the Ukrainian civil war”, and which, like Russian president Vladimir Putin, emphasises the role of “fascist” elements in Ukrainian politics. Though the editorial is rightly critical of the role that NATO has played in engendering the conflict, its main function is to exempt Russia from the charge of imperialism, reserving this for the US and its allies.

The opposite mistake is made by figures such as Paul Mason, a journalist and former Trotskyist, who views the conflict as a battle between the “the globalist, democratic former imperialist countries of the US and European Union versus the authoritarian, anti-modernist dictatorships of China and Russia”:

It is rivalry between capitalist power blocks, but it contains numerous just wars of resistance for national liberation and democracy. And, like it or not, it is a conflict between a democratic, socially liberal model of capitalism and an authoritarian, socially conservative one.

It is quite remarkable to propose that the US and European powers are no longer imperialist. Yet, in Mason’s view, the conflict requires that the left seek to prop up “socially liberal capitalism” in its contest against Russian authoritarianism. This represents the logical development of the position that Mason and some others on the left took during the Brexit referendum: to defend the neoliberal centre, represented by the EU, against the forces of the authoritarianism that might be unleashed were it to crumble.

A more sophisticated version of Mason’s argument is offered by Gilbert Achcar, an influential figure within the Trotskyist Fourth International. In his recent interventions, Achcar has rejected the notion that the conflict can be seen as an inter-imperialist war and downplays the role of NATO. Instead, he views the struggle through the framework of a straightforward national liberal struggle against an “autocratic and oligarchic ultra-reactionary” Russia, making comparisons with the resistance to the US during the Vietnam War. His conclusion is that the left should support arms shipments to the “Ukrainian state”. On sanctions, he argues that the left should “neither support sanctions, nor demand that they be lifted”.

The problem with these types of position is that they each fail properly to locate the invasion of Ukraine within a system of inter-imperialist competition, pitching imperialists and their allies against one another. Although it is certainly possible to condemn the Russian onslaught without such a conceptualisation, this condemnation is inadequate for two central reasons. First, it detaches the horror in Ukraine from the general brutality of the imperialist system. This includes the ongoing oppression of the Palestinians; the civil war in Yemen, where the Saudi government currently leads a bombing campaign every bit as murderous as that in Ukraine; the Syrian conflict that recently pulverised the country; and the 2003 US-led invasion of Iraq, which led to the death of over half a million civilians. Second, detaching Ukraine from the logic of inter-imperialist rivalries also undermines our capacity to explain the current invasion—thus weakening our efforts to intervene to challenge imperialism.

This analysis will briefly outline how the imperialist system has evolved over time, locate the development of Ukraine—and its relationship to Russia and the West—within this context, and argue for a response from the left that both condemns the invasion and the role the Western powers have played in provoking and escalating conflict in the region.

The imperialist context

Imperialism is best conceived not simply as the domination of weak countries by powerful ones, but also a system of inter-imperialist rivalries, drawing different capitalist states into conflict. It emerges as a distinct stage in the development of capitalism. This stage is a consequence of the firms making up capitalist economies reaching a size where they begin to play a decisive role in national life and in which their operations increasingly spill across national frontiers. Under these conditions there is a growing interdependence of state and capital, in which economic competition tends to fuse with geopolitical competition between states. States are able, through military and other means, to project their power abroad, furthering the interests of their capitalists, but those running states also depend on capitalist development to give them an adequate military and industrial base to do so.

In its early phase, imperialism saw with the creation of formal colonies, along with informal spheres of influence, dominated by one or other of the great powers. Because the development of capitalism is an uneven process, this leads to ongoing struggles to reconfigure patterns of influence, and thus to inter-imperialist clashes. The two world wars reflected the pressure that late-developing capitalisms such as Germany, the US and Japan imposed on the existing imperial order, which was dominated by the older established European powers.

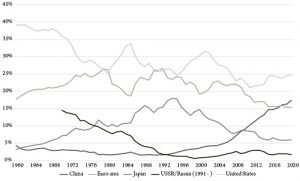

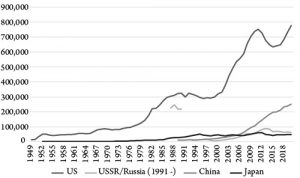

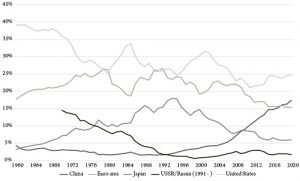

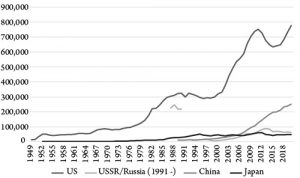

After the Second World War, the configuration of imperialism changed in important ways. Many of the former colonies were able to throw out their rulers, achieving formal independence, even if remaining in a subordinate position economically. Meanwhile, the US’s rulers, having emerged from the war with by far the most powerful economy—a status they maintained in the decades that followed (figure 1)—sought to create an imperialist order based not on colonies but on open markets. Powerful corporations, built around the US’s mass production industries, would possess major advantages in this arena. Meanwhile, the dollar would underpin the global financial system, again conferring advantages on the US. Finally, US military power would outstrip that of any potential rivals within the Western world (figure 2).

Figure 1: Share of global GDP (current US$), 1960-2020

Source: World Bank and United Nations data.

Figure 2: Military spending (millions US$, constant 2019 prices), 1949-2020

Source: Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

During the Cold War, the Soviet Union and its allies were excluded from the liberal market system, instead organising their economies as more or less autarkic “bureaucratic state-capitalisms”, each functioning somewhat like a single giant enterprise, with the state bureaucracy directing production.

The formation of two competing blocs of capitalist powers, with the leading state in each armed with nuclear weapons, led to a “partial dissociation of economic and political power”. In the Western bloc, the Japanese and European economies were reconstructed, the latter increasingly integrated through the forerunners of the EU, under the political and military leadership of the US. Although there could be sharp economic tensions within this bloc, they did not result in military clashes.

The wars that erupted during the Cold War typically took the form of proxy conflicts, in which one or other of the superpowers might intervene directly, but in which both avoided a direct confrontation. The overall global order remained broadly fixed: “Both the US and the Soviet Union, at least in the period of détente in the 1960s and 1970s, were willing to regard themselves and each other as status quo powers with no interest in revisiting the post-war settlement”.

However, preserving and expanding their military capacities placed immense strain on each of the superpowers. In the case of the Western bloc, extremely high levels of military spending in the post-war period helped to sustain the long boom; however, because the costs of this “permanent arms economy” were unevenly shared, this also contributed to the erosion of US economic preponderance in the face of competition from less militarised powers such as Germany and Japan. Meanwhile, the Soviet Union, reliant on more slender economic resources and without access to the emerging global division of labour that was developing in the West, stagnated. Stalinism would be swept away across much of Eastern Europe in 1989; two years later, the Soviet Union itself collapsed.

The end of the Cold War brought about a new phase in the development of imperialism. Initially, there was euphoria among the rulers of the Western camp. As President George H W Bush launched the first US-led war on Iraq in 1991, following Saddam Hussein’s invasion of neighbouring Kuwait, he pronounced “a new world order where diverse nations are drawn together in common cause to achieve the universal aspirations of mankind”:

For some two centuries, the US has served the world as an inspiring example of freedom and democracy… And today, in a rapidly changing world, US leadership is indispensable.

The opportunity presented by the collapse of the Eastern Bloc also led, by the late 1990s, to the start of NATO and the EU’s eastwards expansion, integrating former state capitalisms into the liberal capitalist order. This “unipolar moment” of unrivalled US supremacy was, however, short lived. In the following years, economic and military power would be rearticulated in new and dangerous ways.

This was demonstrated in dramatic fashion as the neoconservatives clustered around the administration of the younger Bush, George W, seized on the attacks in the US on 11 September 2001 to initiate the “War on Terror”. Here, the US’s colossal military advantages were to be used to shore up the country’s economic power. The invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq were supposed to demonstrate to potential rivals—in particular, China, now identified as the major long-term threat to US hegemony—that access to the vast oil reserves of the Middle East depended on US goodwill. In the event, the War on Terror proved disastrous, further weakening the grip of US imperialism.

The rise of China, meanwhile, prompted its own rulers to begin to develop a military capacity appropriate to their economic power. According to a 2020 report prepared for the US Congress, this involved striving for at least equivalence with the US military by 2049. The report claims that China already has superiority in shipbuilding, possessing the largest navy in the world; in “land-based conventional ballistic and cruise missiles”; and in integrated air-defence systems. Though it shows no sign of seeking to displace the US at a global level, China already threatens regional US hegemony—particularly in the South and East China Seas.

The resulting tensions between the US and China today constitute the main faultline in world politics. However, this does not mean the straightforward recapitulation of the Cold War. Even though China is excluded from the system of political alliances created under US leadership since the Second World War, it is highly integrated into global circuits of capitalism. Although this does not preclude future military clashes between the two biggest powers—after all, Germany and Britain were highly integrated prior to the First World War—it does imply a complex pattern of interdependence and rivalry. Within this increasingly unstable order, several less powerful imperialist or sub-imperialist powers have also been able to assert themselves at a regional level. This is reflected in the efforts of Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Iran, the United Arab Emirates and others to intervene in conflicts such as those in Syria and Yemen to try to shape the outcome in their own interests.

Russia’s growing efforts to reassert itself in its own “near-abroad” and the plight of Ukraine should also be situated in this context of inter-imperialist rivalry.

Ukraine and Russia

For much of its history, Ukraine has been subject to the control of external powers. By the late 17th century, it had become a battleground for several of these, inaugurating a period known as “The Ruin”. The clash, involving the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Russia, the Ottoman Empire and the Cossack Hetmanate, ultimately left much of present-day Ukraine partitioned between Poland and Russia. As Poland itself lost its independence, the Russian Empire absorbed the east of Ukraine, while, to the west, Galicia and western Volhynia were absorbed by Austria. These borders would be called into question by the First World War and the revolutions that helped to end it. Efforts to establish an independent Ukraine following the 1917 Russian Revolution were complicated, to put it mildly, by German occupation and then by the post-revolutionary civil war, in which Ukraine was a major battleground. Amid the chaos, Poland, which had now regained sovereignty, also managed to take control of Galicia and most of Volhynia. By 1922, with a pro-Soviet regime in power in areas of Ukraine outside of Polish control, albeit one dependent on support from Moscow and the Red Army, the Soviet Union was proclaimed by the Russian, Ukrainian, Belarusian and Transcaucasian republics.

For all the complexities, and the desperate struggle to preserve the 1917 Revolution, early Bolshevik policy was built around the right of formerly oppressed states to determine their own destiny. As Leon Trotsky put it:

The right to self-determination, that is, to separation, was extended by Lenin equally to the Poles and to the Ukrainians… Every inclination to evade or postpone the problem of an oppressed nationality he regarded as a manifestation of Great Russian chauvinism… In the conception of the old Bolshevik Party, Soviet Ukraine was destined to become a powerful axis around which the other sections of the Ukrainian people would unite.

However, early attempts by the Bolsheviks to promote the Ukrainian language and culture, along with efforts to improve social conditions, were short lived, falling victim to the broader reversal of the gains of the revolution under Stalin. As Trotsky argues: “To the totalitarian bureaucracy, Soviet Ukraine became an administrative division of an economic unit and a military base of the Soviet Union”. Not only was there a crushing of any aspiration to independence, the collectivisation of farming associated with Stalin’s attempts at rapid industrialisation would lead in 1932-3 to a famine, known as the “Holodomor”, in which several million Ukrainians died.

When the Second World War broke out, Ukraine was again subject to the predations of rival imperialisms. In the first phase of the war, under the Hitler-Stalin pact, Poland was partitioned. Then, when Germany launched its invasion of Russia, Ukraine was overrun. Some seven million Ukrainians lost their lives. This included around a million Jewish people, including those killed at the infamous Babi Yar ravine in Kiev, where tens of thousands were shot and dumped in mass graves. Tragically, a minority of Ukrainians sought to align themselves with Nazi Germany in this conflict, including the followers of Stepan Bandera, a figure rehabilitated by recent governments in Kiev. The war ended with the Soviet army expelling Germany forces, reunifying the east and west of Ukraine.

Looking at this history of oppression and bloody warfare, it is hard to disagree with historian Tim Snyder’s comment: “When Hitler and Stalin were in power, between 1933 and 1945, Ukraine was the most dangerous place on earth”.

The collapse of the Soviet Union was the first time a relatively stable and independent state was able to form within the borders of present-day Ukraine. It was a far from ideal moment for nation-building. Not only did independence occur in the wake of the stagnation of the Soviet Union, but worse was to follow. With the support of Western advisers, Russia, and a little later Ukraine, were subjected to neoliberal shock therapy to introduce a market economy. As political economist Isabella Weber puts it:

Shock therapy was at the heart of the “Washington consensus doctrine of transition”…propagated by the Bretton Woods institutions in developing countries, Eastern and Central Europe and Russia… The package consisted of (1) liberalisation of all prices in one big bang, (2) privatisation, (3) trade liberalisation, and (4) stabilisation, in the form of tight monetary and fiscal policies.

As Weber points out, privatising an entire economy previously based on state ownership goes well beyond the limited privatisations carried out by figures such as Margaret Thatcher in Britain. When Boris Yeltsin, Russia’s first post-Soviet era president, imposed price liberalisation in January 1992, the result was not an orderly transition to a market system, but prolonged price inflation and collapsing output. Instead of a new class of private entrepreneurs spontaneously developing, those who ran enterprises under the old state capitalist model, the so-called nomenklatura appointed by the Communist Party, sought to reinvent themselves as private capitalists. Some enterprises had already had their assets transferred illegally into private ownership through “spontaneous privatisations”. Now, in “voucher privatisations”, citizens were given vouchers that could be exchanged for cash or shares in enterprises. These traded on poorly regulated secondary markets and ended up in the hands of those “with large amounts of hard currency and connections”. Workers and managers in enterprises received preferential rates when they purchased shares, but workers often found their shares were “locked in trusts controlled by managers”.

It was out of this chaos that the oligarchs—rich and powerful individuals operating at the nexus of economic and political power—emerged in Russia and other post-Soviet states. Ukraine embarked on its privatisation programme more slowly than Russia, but it followed a similar pattern. As swathes of the economy collapsed, much of the wider population was plunged into deepening poverty.

In Russia, what growth there was came to depend on the export of primary goods, particularly oil and gas, the proceeds of which were largely funnelled abroad. Alongside this came wild financial speculation and endemic corruption. At one point, the rate of creation of new banks reached 40 a week. As the instability of this model of growth became clear, pressure grew on the rouble, whose value was propped up through an expansion of state debt. It took the 1998 East Asian financial crisis to trigger a full-scale currency collapse, a Russian default on its loans and a new phase of economic chaos.

Ukraine suffered many of the same problems but lacked even the energy resources accessible to Russia to cushion its economy. Instead, it depended largely on agriculture; what industrial base it had possessed before 1991 centred on military production, which became unsustainable without Soviet procurement programmes. Its transition was one of the most catastrophic among the former Eastern Bloc states, with the country remaining, to this day, by most measures, the poorest in Europe. The per capita GDP figures below (table 1) are all the more remarkable when one realises that the population has fallen from over 52 million in 1993 to around 41 million today—a result of rising mortality, declining births and huge levels of emigration.

Table 1: GDP per capita (current US dollars)

|

|

1990

|

1995

|

2000

|

2005

|

2010

|

2015

|

2020

|

|

Ukraine

|

1569

|

936

|

658

|

1895

|

3078

|

2125

|

3725

|

|

Russia

|

3493

|

2666

|

1772

|

5324

|

10675

|

9313

|

10127

|

|

Poland

|

1731

|

3687

|

4502

|

8022

|

12613

|

12579

|

15721

|

|

Romania

|

1681

|

1650

|

1660

|

4618

|

8214

|

8969

|

12896

|

Source: World Bank data.

A clash of imperialisms

As noted above, the 1990s, a period of sudden weakening of Russian influence, saw a push to expand both the EU and NATO towards Russia’s frontiers (figure 3).

Figure 3: NATO’s eastward expansion in Europe

Poland, Hungary and Czechoslovakia (later Czechia and Slovakia) had formed the Visegrád group as early as 1991 to press for both EU and NATO membership. However, it was under Bill Clinton’s US administration that expansion truly gathered pace. The 1999 NATO summit, held in Washington, formalised expansion into Hungary, Poland and the Czech Republic, and announced “Membership Action Plans”—a newly created procedure for would-be members—for Albania, Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, North Macedonia, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia.

Incorporation of the Baltic states in 2004 meant that former Soviet states bordering Russia were now part of a military pact viewed as hostile by Moscow. As Strobe Talbott, Clinton’s deputy secretary of state, put it:

Many Russians see NATO as a vestige of the Cold War, inherently directed at their country. They point out that they have disbanded the Warsaw Pact, their military alliance, and ask why the West should not do the same.

The eastward march also breached the understanding reached with the last Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, during 1990-1 talks that allowed a newly unified Germany to remain in NATO.

Despite its economic collapse, Russia remained an imperialist power. Now it sought to secure its borders, preventing other regions breaking away, and to restore its influence in its own “near abroad”. In the 1990s, this involved it in three major conflicts. Each reflects the way in which the patchwork of nations, languages and ethnicities absorbed into the Russian Empire, and later the Soviet Union, created scope for the promotion of rival versions of nationalism, many of them rooted in genuine experiences of national oppression. In the aftermath of the collapse of the Soviet Union local ruling classes could seek to build a base of support by promoting various nationalisms, and so too could imperialist powers looking to manipulate the resulting tensions in their own interests.

So, in Transnistria, on Moldova’s eastern border, separatists played upon attempts by the government to impose Moldovan, a Romanian dialect, on the region, even though only about a third of the population there were of Moldovan origin. Transnistria declared itself independent in 1991. A brief war in 1992, in which separatists were supported by Russian troops stationed in the area, along with Russian Cossacks, established a de facto state. The legacy was one of a series of “frozen conflicts”—unresolved clashes with the potential to be reignited by Russia and local leaders if the balance of power in the region looked as if it might shift against them. In particular, the conflict in Moldova acts as an impediment to the country’s attempts at EU membership, a formal application for which was issued in March this year during the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

A second frozen conflict developed in another former Soviet state, Georgia, when two regions with significant non-Georgian populations, Abkhazia and South Ossetia, sought to break away, the former waging a war in 1992-3 with Russian support. Georgia, like Moldova, applied to join the EU in the wake of the invasion of Ukraine, but is unlikely to be accepted while the separatist regions function effectively as separate states under Russian protection.

By far the most brutal conflict was fought within the Russian Federation’s own borders, in Chechnya, a region of the Caucasus bordering Georgia. Here the collapse of the Soviet Union was met with demands for independence, which was proclaimed in November 1991. After a failed attempt by Moscow to subvert the government, a full-scale Russian assault began in 1994. Yeltsin calculated that crushing the Chechen movement would not only preserve Russian influence in the Caucasus, but also secure control of routes for lucrative oil pipelines from the Caspian Sea and restore his now flagging popularity. However, the offensive met considerable resistance, drawing on a long history of opposition to Russian oppression. As the war escalated, the shelling of the capital, Grozny, left an estimated 27,000 dead. With the country’s infrastructure destroyed, a popular insurgency took hold, combining urban and guerrilla warfare, and fighting the Russian army to a standstill. A ceasefire was signed in 1996, by which time around 80,000 Chechens had died.

The destruction of Chechnya led to an explosion of criminality and warlordism, along with the rise of Islamist groups, and this provided the pretext for a second invasion. A land assault took place from 1 October 1999 to 31 May 2000, with the counter-insurgency campaign continuing a further nine years. By the end of 2002, there were, according to one estimate, 190,000 dead—17,000 Russian forces, 13,000 Chechen fighters and 160,000 civilians. Putin’s rise came in the context of this Second Chechen War. Yeltsin had appointed Putin, a former KGB officer and presidential chief of staff, as prime minister in autumn 1999. Just one year later, he succeeded Yeltsin as president.

Despite the carnage in Chechnya, Putin was at first feted by Western leaders. Tony Blair would describe him in 2000 as a leader who “talks our language of reform”, adding: “I believe that Vladimir Putin is a leader who is ready to embrace a new relationship with the EU and the US”. This view would be relatively short-lived. As the Russian economy rebounded from the recession of 1998, buoyed up by rising energy prices, Putin sought to consolidate his rule, to further extend Russian influence abroad and to push back against NATO’s advance. The partial restoration of Russian power that took place from this time was unwittingly assisted by the US-led invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, which drove a sharp rise in energy prices and, through their failure, created greater space into which rival imperialisms could insert themselves.

The Orange Revolution

Ukraine found itself at the seamline of the resulting clash of imperialisms, with these external tensions finding an echo in the country’s domestic politics. That is not to say that we should accept a simplistic concept of “two Ukraines”, which severs the country neatly into pro-Russian and pro-Western constituencies. Although it is true that the country has a substantial Russian minority concentrated in the east, there are multiple, overlapping differences of ethnicity, culture, language and religion, reflecting the country’s complex history, including its domination by external powers. Moreover, as Rob Ferguson argues, bilingualism has tended to rise—at least up to 2010—particularly among the young: “Most ethnic Ukrainians and Russians are bilingual. They intermarry and converse in both languages”.

Nonetheless, Ukraine’s oligarchic elite has sought to manipulate the divisions, as well as appealing to sources of external support such as Russia, the US and the EU. Yuliya Yurchenko argues: “In order to service their accumulating ambitions, fractions of the competing…capitalist class of the newly emerged kleptocratic regime designed political shell parties… Although the fractioning of the ruling and capitalist class bloc is real, the political differences between them are arbitrary”. In particular, she identifies two key blocs, originating from the industrial regions of Dnipropetrovsk in central Ukraine and Donetsk to the east, that have tended to dominate the country’s political system.

In this context, popular movements risk being subverted in the interest of imperialist powers or sections of the domestic elite. During the cycle of “colour revolutions” in Eastern Bloc states—Serbia in 2000, Georgia in 2003, Ukraine in 2004 and Kyrgyzstan in 2005—Ukraine was probably the instance with least genuine popular initiative and the highest degree of manipulation.

The immediate context for Ukraine’s Orange Revolution was the departure of President Leonid Kuchma after two terms in office. Kuchma was close to the Dnipropetrovsk capitalists but had to accommodate the growing power of those emerging from the Donetsk region. He also sought to balance between the US and Russia, seeking to secure loans from the Western financial institutions and cheap gas from Russia. By 2004, his regime was hated for its corruption, fraud and criminality—including the suspicious death of a Ukrainian journalist critical of the political elite.

When a fraudulent election gave the presidency to Viktor Yanukovych, the main candidate of the ascendant Donetsk capitalists, and backed by both Russia and Kuchma, his rival, Viktor Yushchenko, backed by the Dnipropetrovsk capitalists, some of the Donetsk oligarchs, the US and the EU, called on his supporters to take to the streets. This they did, and a well-prepared protest camp was funded by Yushchenko’s wealthy patrons—including US foundations and Ukrainian NGOs backed by the US State Department. Initiative shifted quickly away from the streets and into Ukraine’s Supreme Court, which ruled that the election had to be re-run. Yushchenko emerged victorious and appointed another Orange Revolution leader, Yulia Tymoshenko, an influential Dnipropetrovsk oligarch turned politician, as his prime minister. Yushchenko rapidly began to drive through legislation aiming at closer relations with—and ultimately integration into—the EU and a rapprochement with NATO. Within months, Tymoshenko, who had declared a “war on the oligarchs” through which she sought to settle scores with her rivals, was forced out by Yanukovych’s supporters in parliament. She would again assume the role after 2007 elections, when her party gained seats in parliament, but the squabble between the two leaders of the Orange Revolution now dominated politics, undermining Yushchenko’s rule.

Moreover, the Yushchenko-Tymoshenko government was about to confront three major crises that erupted in 2008. First, there was the global economic meltdown that began that year. Ukraine was hit particularly hard as its weak banking system seized up and the market price of steel, one of its major exports, slumped. Those Ukrainians who had taken advantage of loans or mortgages issued in dollars found they could not repay them as the local currency collapsed.

Second, there was a sudden reassertion of Russian power as it warmed up its frozen conflict in Georgia. The Russian move came in the wake of the Bucharest NATO summit that had acceded to Bush’s push to expand the alliance. According to the official declaration on 3 April 2008:

NATO welcomes Ukraine’s and Georgia’s Euro-Atlantic aspirations for membership in NATO. We agreed today that these countries will become members of NATO. The Membership Action Plan (MAP) is the next step for Ukraine and Georgia on their direct way to NATO membership. Today, we make clear that we support these countries’ applications for MAP.

Two weeks later, Putin recognised the breakaway regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. When, in August that year, Georgian troops entered South Ossetia in response to the shelling of Georgian villages, Russia launched a full-scale offensive, forcing the Georgian army into a humiliating retreat.

Third, a brewing dispute between Russia and Ukraine over gas supplies came to a head. Already, in 2006, Russia had briefly cut off its supply to Ukraine after accusing it of diverting supplies away from their intended markets in the EU. Now, a dispute over debts owed by Ukraine to Russia led to new disruption to supplies, impacting not just Ukraine but 18 European countries reliant on Russian gas.

The failure of the Yushchenko-Tymoshenko period to bring about the radical change promised by the Orange Revolution, along with these multiple crises, allowed Yanukovych to capture the presidency. He won the 2010 election and proclaimed a “balanced policy”—continuing to promise cooperation with the EU but pulling back from the aspiration for NATO membership.

NATO was, anyway, by now deeply divided over its expansion policies. France and Germany had already blocked granting immediate membership action plans to Ukraine and Georgia at the April 2008 summit, and now they would double down on this, preventing any further steps towards membership. The continental European powers were highly dependent on supplies of gas from Russia, home to the world’s largest reserves. Indeed, the German government had, against the wishes of the US, Britain, Poland and Ukraine, invited Russia to build a new gas pipeline, Nord Stream 2. This would run in parallel to the existing Nord Stream 1, conveying gas directly from Russia to Germany—the plans were shelved only in 2022 as the invasion of Ukraine took place. France was not quite as dependent as Germany on Russian gas, which, prior to the invasion, covered about half of Germany’s needs and a quarter of France’s. However, France has also sought to assert an independent role for the EU, and a reduced role for the US, in relations with Russia.

Maidan, Crimea and the Donbas

By the time Yanukovych came to power in Ukraine, the government was desperate for hard currency to bail out the stuttering economy. In an effort to secure external backing, Yanukovych flirted with both Russia and the EU. Russia offered Ukraine entry to a customs union, alongside Belarus and Kazakhstan, while the EU offered a free trade agreement, together with an association agreement designed to pave the way for eventual membership. As one journalist put it:

Yanukovych had hoped for generous concessions on Russian gas prices that would help him arrest Ukraine’s plunging economy. Instead he received a small temporary price drop—further evidence, if any were needed, that Putin is unwilling to dole out favours for free. Putin offered to slash gas prices by nearly 40 percent…but only if Kiev accedes to the customs union… The International Monetary Fund has suspended loans to Kiev because Yanukovych refused to make the belt-tightening measures recommended by the IMF due to fears that they would lose him votes. However, Moscow’s intransigence about gas prices could yet propel Kiev towards the EU choice.

Yanukovych’s ultimate refusal to sign the deal with the EU led to the Maidan protests in 2013-14, initially involving students and young people who resented the misrule of the Ukrainian oligarchs and saw the EU as providing an alternative. It was when the president unleashed interior ministry troops, known as the Berkut (“golden eagles”), to break up these protests that the movement was transformed into one involving hundreds of thousands. The Maidan protests, named after the central square in Kiev, spread throughout central and western areas of the country.

A variety of different forces were involved in the demonstrations. Many ordinary protesters were sceptical about the entire political set-up in post-1991 Ukraine and hoped to see significant changes, and many more were angry at the police repression; however, very few claimed, when polled for their view, that they were there because of the calls of opposition politicians. Nonetheless, in the absence of a credible organised force capable of challenging the established order, pro-Western oligarchic parties would emerge as the movement’s official representatives. Alongside these were a highly visible minority of fascists and far-right nationalists associated with the Right Sector organisation. Although the portrayal of the movement as a “fascist coup d’etat” by the Russian state media is a myth, these forces were nonetheless among the most organised and visible in confronting the Berkut.

As the movement grew, Yanukovych fled to Russia and his party began its disintegration. The official opposition stepped in the vacuum. Fearful that Ukraine might depart entirely from its sphere of influence, Russia annexed Crimea, which already hosted a naval base leased by Russia and was home to its Black Sea fleet. Crimea was a bridgehead into eastern Ukraine. Veterans of Russia’s prior proxy wars moved into the Donbas region and began an uprising against the government. There is little evidence that the majority in Donetsk and Luhansk supported separatism. Nevertheless, deadly clashes in which 42 Russian nationalists were killed in Odessa and Kiev’s reliance on militias, often linked to the far-right, to substitute for the dilapidated Ukrainian army helped fuel the separatist cause. In Donbas:

The conflict gradually grew into a full-scale war with a flow of volunteers, supply of arms, and equipment from Russia, and ultimately an incursion of Russian regular forces during the decisive fighting in August 2014… Two rounds of international negotiations in 2014 and 2015 in Minsk, Belarus, led to an agreed road map for political solution of the conflict; however…a stable ceasefire failed to be secured.

Ukraine now had its own frozen or, rather, simmering conflict.

Petro Poroshenko, one of the wealthiest oligarchs in Ukraine, now won the presidency, ushering his allies into positions of power and influence. The EU association agreement was signed, and later the constitution was amended to commit the country to join both the EU and NATO. Roughly $1.8 billion in US military aid would pour into the country over the next six years. A $3.9 billion International Monetary Fund loan was obtained, in exchange for which the government agreed to raise household gas prices and impose cuts to its budget deficit. Together with continued rampant corruption, the resulting austerity programme led to Poroshenko’s crushing defeat in the 2019 presidential election. His successor, Volodymyr Zelensky, stood as a political outsider, best known for playing a character who wins Ukrainian presidency in a hit comedy show. After his landslide victory, many expected Zelensky would finally tackle corruption, tame the oligarchs and end the conflict with Russia.

In fact, following a brief early phase of anti-corruption measures up to March 2020, Zelensky’s reforms quickly stalled as the government sought to balance between competing imperialist forces externally and rival groups of oligarchs internally. This included some increasingly influential oligarchs with Russian connections, particularly Viktor Medvedchuk, who was able to massively expand his media empire during these years. By early 2021, the popularity of Zelensky and his party had fallen considerably.

Meanwhile, Moscow, initially hopeful of obtaining concessions from Zelenksy, claimed increasing frustration at the failure to implement the “Minsk agreements”, which would have reintegrated Donetsk and Luhansk into Ukraine with a special autonomous status. If Zelensky was unwilling to yield to pressure from Russia, his most likely successors among the opposition forces were felt by Moscow to be even less pliant. Moreover, the inauguration of Joe Biden as US president in early 2021 suggested that pressure might grow in Ukraine for reform. Indeed, Zelensky did now begin to target specific oligarchs—particularly those deemed problematic by Washington, such as Medvedchuk and Ihor Kolomoisky, whose “1+1” channel used to broadcast Zelensky’s television shows.

It was in this context that the build-up of Russian troops on the Ukrainian border began in spring 2021, accompanied by demands that Washington honour Russian security interests. Biden, whose presidency had stuttered since he announced the US withdrawal from Afghanistan, hoped to restore his fortunes by calling Putin’s bluff, setting in motion a spiral of escalation.

Following the pattern of previous conflicts, such as that in Georgia, Moscow first gave official recognition to the two breakaway regions in Ukraine before launching an invasion.

Responses to the invasion

The response of Zelensky has been to seek to draw the Western powers into the conflict—a request that met with its most positive response from Central and Eastern European countries drawn into the EU or NATO. Biden has been more muted when it comes to direct involvement, France and Germany even more so. Thus far, calls from Zelensky and others for a “no fly zone” over the country have been resisted. Such an initiative would be a disaster—making a direct military clash between NATO and Russia almost inevitable. The US has also rejected a Polish plan to transfer MiG-29 fighter jets to the US and then on to Ukraine. A Pentagon spokesperson commented: “The prospect of fighter jets ‘at the disposal of the US government’ departing from a US base in Germany to fly into airspace over Ukraine that is contested with Russia raises serious concerns for the entire NATO alliance”.

However, the West has escalated the conflict in two other ways. First, there is indirect military support. This includes a package of $3.5 billion in military supplies authorised by the US Congress in March, and a further $3 billion to deploy US forces in allied countries in Europe and to provide intelligence support. Military aid includes portable drones that detonate on impact with their target, Stinger anti-aircraft missiles, Javelin anti-tank weapons and the Patriot air defence missile system. Germany has reversed its historic policy of not sending weapons to conflict zones. The country’s new chancellor, Olaf Scholz of the Social Democratic Party, also pledged to spend €100 billion to renew the German armed forces and increase its defence spending to above 2 percent of GDP.

Second, there has been an extensive sanctions programme. What began as a commitment to target oligarchs connected to Putin evolved in a matter of days to become a broader assault on the Russian economy. This included the US pushing through, in the face of some resistance from Europe, the exclusion of many Russian banks from the SWIFT messaging system, making foreign financial transactions more difficult. This was followed by a far more powerful move, as the US, EU, Japan and Switzerland coordinated to freeze Russian Central Bank assets aboard and ban transactions with the bank. As James Meadway argues, this reflects the way that central banks have been weaponised in recent years. The role of the European Central Bank in forcing through EU bailout programmes in Ireland and Greece during the European debt crisis of the early 2010s offer cases in point.

These moves should be resisted. The idea that the economic warfare being waged by the West on Russia can be neatly separated from military confrontation ignores the whole logic of imperialism, which is premised on the integration of economic and geopolitical conflict. This was made entirely clear by Putin, who responded to the moves, along with frustration at the progress of the Russian military on the ground, by raising the alert level of his nuclear forces. These measures form part of an “escalatory spiral” between nuclear-armed powers at a time when the left should be seeking de-escalation. Moreover, the indiscriminate nature of the sanctions, which are likely to cause a collapse in the value of the rouble and a major recession in Russia, will result in untold suffering among the mass of ordinary people. There is also very little evidence that sanctions have historically led to rapid shifts in policy, as shown by North Korea and Iran.

Beyond the West, the response has been far more mixed, a fact that can be obscured by the blanket condemnation of Russia in the Western media. Saudi Arabia, for instance, historically a key US ally, has stood aloof from condemnation of Russia. In part this reflects the way that the US has emerged as a competitor to Saudi oil exports—along with growing Saudi-Russian cooperation to maintain high prices through the OPEC+ group of countries. It also reflects the US-Saudi tensions over the murder of dissident journalist Jamal Khashoggi and limited US support for the Saudi-backed forces in Yemen. Similarly, the United Arab Emirates abstained on the UN security council vote demanding Russian withdrawal.

Other countries such as South Africa and India have also avoided joining the Western chorus of attacks on Russia. Indeed India, which has ties to Russia stretching back to the Cold War and fears the growing alliance between Russia and its neighbour and rival, China, has gone further. Its central bank has engaged in talks to create a rupee-rouble trade arrangement to circumvent the sanctions, following a similar mechanism used to buy Iranian oil in the past.

However, it is the role of China that may prove most decisive. Prior to the invasion, Russia and China had drawn closer, issuing a joint statement in February announcing a friendship with “no limits” and “no ‘forbidden’ areas of cooperation”. However, this is a friendship in which China, whose economic weight and military spending now far exceeds those of Russia (figures 1 and 2), is the senior partner. As noted above, US-China relations involve both mutual dependence and antagonism, and China will have to weigh its desire to see NATO weakened against its desire to retain access to Western markets and the global financial system that still rests heavily on the dollar and Western central banks. At the time of writing, China had criticised the role of NATO expansion in precipitating the war but abstained at the crucial UN security council vote, rather than openly back Russia. US policy has been to seek to prevent China answering Russia’s call for economic support and weapons. Indeed, Biden has described a series of “implications and consequences if China provides material support to Russia” in calls to President Xi Jinping.

As Mike Davis argues, this also reveals something of the nature of Biden’s regime, which has rapidly lost any progressive gloss it once had:

All the think-tanks and genius minds that supposedly guide the Clinton-Obama wing of the Democratic Party are in their own way just as lizard-brained as the soothsayers in the Kremlin. They can’t imagine any other intellectual framework for declining US power than nuclear-tipped competition with Russia and China… In the end, Biden has turned out to be the same warmonger in power that we feared Hilary Clinton would be. Although Eastern Europe now distracts, who can doubt Biden’s determination to seek confrontation in the South China Sea—waters far more dangerous than the Black Sea?

Social impacts

As this suggests, the issues posed by the Russian invasion go far beyond the immediate geopolitical implications for the region. It has often been said by radical left-wing opponents of war that military interventions have social consequences—that they can ratchet up class antagonisms at home—but the social impact of this war is far more immediate than most.

Economies such as Britain’s were already experiencing their sharpest acceleration in inflation for decades, driven to a large extent by rising food and energy costs. Now a further spike in oil and gas prices has heightened the risk of stagflation—a simultaneous rise in price levels combined with a collapse in output. According to one Goldman Sachs economist, a complete ban on EU imports of Russian energy would cut production by 2.2 percent, enough to trigger a recession across the Eurozone. British chancellor Rishi Sunak has informed colleagues that he expects the impact would be far greater, leading to a 3 percent contraction in the British economy.

Just as horrifying has been the unseemly rush to identify other carbon-based fuels to replace dependence on Russian supplies. This led to Boris Johnson reopening the debate about fracking in Britain and threatening to reverse the moratorium imposed in November 2019. The other strand of government policy appears to involve cosying up to Saudi crown prince Mohammed Bin Salman. Johnson flew out to a meeting with the prince immediately after the execution of 81 people in the kingdom, with three more killed while the British prime minister was in Riyadh. Johnson sought to evade any questions about possible parallels between the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the Saudi-led bombing campaign in Yemen, which is thought to have directly killed at least 15,000 civilians.

Yemen is also one of the countries likely to suffer yet more horror due to the rise in food prices and the disruption of wheat imports due to the conflict. This is just one consequence of a wider disruption to food supplies due to the invasion. Roughly one-third of global wheat exports come from Ukraine or Russia, and about half of the grain provided by the UN World Food Programme. The disruption is likely to impact upon 44 million people worldwide already on the brink of famine. Beyond this, there will be sharp increases in the price of food in countries such as Egypt, Indonesia, Morocco, Pakistan and Tunisia that rely on wheat imports.

Stopping the war

How should the left respond to all this? In countries such as Britain, the entire mainstream political establishment has united not just to denounce Russia, but also to silence any criticism of the role of NATO and the EU in engendering conflict in Ukraine. This has involved sharp criticism of organisations such as the Stop the War Coalition (STWC), which was launched in 2001 to oppose the wars on Afghanistan and Iraq, and which has condemned both the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the NATO expansion that preceded it.

In the case of the Labour Party, the ferocity of the attacks reflects the desire of party leader Keir Starmer to crush the legacy of his predecessor, Jeremy Corbyn, who rose to prominence in part through his association with STWC. Just 11 Labour MPs signed a STWC statement on the conflict—and every one of them, including prominent left figures such as Diane Abbott and John McDonnell, withdrew their names under pressure from Starmer. This is a deeply worrying sign, demonstrating the current impotence of those who prioritise maintaining the unity of the Labour Party over constructing a vibrant, internationalist left outside parliament.

The relative narrowing of the base of support for the anti-war movement compared to the period of the Afghanistan and Iraq wars should not be grounds to abstain from protesting. At the time of writing, it was unclear how long the conflict would last or how far it might escalate. Even if a ceasefire is achieved, the gradual erosion of US hegemony, combined with the multiple crises that capitalism today faces, will ensure further inter-imperialist clashes. In that context, we should remember how much more isolated the revolutionary left were at the outbreak of the First World War, when mainstream socialist parties were swept up in the clamour to support their own ruling classes. Trotsky recalled the tiny scale of the first Zimmerwald conference to oppose the war in 1915: “Delegates joked among themselves about the fact that half a century after the founding of the First International, it was still possible to seat all the internationalists in four coaches”. Three years later, revulsion at the conflict, together with deepening class antagonism, drove the revolutions in Russia, Germany and Austria-Hungary that ended the war.

The approach of Trotsky, Lenin and their co-thinkers to the First World War is in many ways a model. They recognised it as an inter-imperialist conflict, pitching big capitalist powers against one another in their effort to plunder and exploit the rest of the world. However, they also asserted, in the words of the German revolutionary Karl Liebknecht, that “the main enemy is at home”. It was the responsibility of socialists to direct their energies and actions against their own ruling class—and to stand in solidarity with those internationally doing the same.

We should therefore take heart from the presence not just of those resisting in the West, but also within Russia itself. The scale of arrests—some 14,000 by mid-March—demonstrates both the level of internal repression in Putin’s Russia and the scale of the protests themselves. Opposition to the war was not the majority sentiment in Russia in the initial phases of the conflict. Support for an invasion probably ran at about 60 percent in February. Moroever, Putin retained high approval ratings. However, even official sources suggest lower levels of support than during the war in Chechnya and the annexation of Crimea. There is also evidence that opposition to war is strongest among young people, those living in cities of more than a million, and those who have seen their economic position deteriorate over the past year. This might open the possibility of the movement gaining traction in at least some sections of the working class.

Much will also depend on what happens on the ground in Ukraine. Here, rather than calling for the channelling of arms from the West in an effort to wage a proxy war against Russia, we should celebrate examples of popular mobilisation against the occupation. This includes the demonstration in Kherson, in the south of the country, where 2,000 protested against Russian troops, telling them, “Go home!” Given the level of casualties experienced by the invading army, and the apparent demoralisation of the Russian soldiers taking part, such protests can have an impact.

Ultimately, it is through a movement from below, centred on working people, whether located in Kiev, Moscow, London, Berlin or Washington, that the drive to war can best be challenged and the logic of inter-imperialist conflict weakened.

Joseph Choonara is the editor of International Socialism. He is the author of A Reader’s Guide to Marx’s Capital (Bookmarks, 2017) and Unravelling Capitalism: A Guide to Marxist Political Economy (2nd edition: Bookmarks, 2017).

Notes