Recent months have been full of ominous signs of deepening conflict between the major players in what Alex Callinicos calls the “multi-level chess game” of Middle Eastern geopolitics.1 In March 2018, Turkish forces entered Syria, forcing tens of thousands to flee the Afrin region, which has a largely Kurdish population.2 A few weeks later, more barrages of missiles struck what Israeli spokesmen claimed were Iranian targets in Syria.3 The long-running conflict in Syria has been the crucible for several of these developments. But the trajectories of civil war and external military intervention there and in Yemen reflect underlying processes of change in the balance of power between states and capitals at regional and global levels. Donald Trump’s apparently disruptive policy shifts—such as moving the embassy of the United States to Jerusalem and pulling out of the nuclear deal with Iran—are often presented (by the president himself as much as by others) as being driven by his erratic personality or by pressures from his domestic electoral constituencies.4 Yet these decisions are also shaped by the changing dynamics of imperialist competition in the region and at a global level to which the US ruling class is attempting to adapt.

Following the work of writers in the tradition of this journal, such as Chris Harman and Alex Callinicos, and earlier generations of Marxist thinkers, including Lenin and Bukharin, this article sees the drive towards war as rooted in the dynamics of capital accumulation itself. Competition between capitals, and thus between the states on which they are structurally dependent, leads to the fusion of processes of military and economic competition between the most powerful capitalist states.5 This means not only considering the interactions of the major powers from outside the region (primarily the US, European powers, such as France and the UK, and Russia), but also regional states which are locked into a sub-imperial system reproducing “a version of the same dynamic that led to the rise of capitalist imperialism in the first place”.6 Imperialism is not simply a label for the predatory behaviour of the strongest states. Nor is it the sole prerogative of the US and its allies. Moreover, the logic of capital accumulation means that “resistance” by the ruling classes of weaker capitalist states to the depredations of the global capitalist powers inevitably reproduces the processes of imperialism at the lower levels of the system. This does not mean that socialists can afford to take an agnostic position in relation to such conflicts. Rather, what is often required is the capacity to mount a principled defence of the weak from the attacks of the strong, while articulating a strategy of how to build genuine resistance to imperialism, which must develop from below and ultimately requires removing from power the coteries of generals and businessmen (whether they style themselves republican or royalist) whose hands are steering the region towards further wars.7

The development of a sub-imperial system is predicated on the emergence of centres of capital accumulation outside the historic core of the capitalist system, which often in turn depended on the ruling classes of the states on the system’s “periphery” breaking out of the colonial political and economic order that trapped them in the role of producers of raw materials and captive markets for manufactured goods in the imperial “mother” countries. This did not of course mean that they were able to escape from imperialism altogether. As Callinicos notes, during the course of the 20th and 21st centuries, the US ruling class has generally pursued the creation of an empire where its hegemony over large areas of the globe beyond its own borders has not depended on setting up colonies or engaging in direct rule. Rather it has looked to other means to make second- and third-rank capitalist states bend to its will.8 Nevertheless, the greater agency enjoyed by these emerging centres of capital accumulation relative to each other, and relative to the major imperialist powers, is an important marker of the difference between the phase of imperialism mapped out by Lenin and Bukharin in the early 20th century and subsequent phases.9

The development of a sub-imperial system in the Middle East10 has to be understood first and foremost through the lens of inequality between competing capitals and “their” states. This inequality is structured into the capitalist system by a range of factors, including the way in which capitalism emerged first in one part of the world rather than everywhere simultaneously, and by the ever-changing positions of the various players in the game. The sub-imperial system in the Middle East has been shaped both by the dynamics of competition between the major capitalist powers—such as the decline of the “old” colonial powers, Britain and France in the early 20th century, followed by the rise of the “new” global imperialist powers the US and USSR, and the eclipse and eventual collapse of Soviet power in the late 20th century—and by similar dynamics between the emerging capitalist states of the region. The economic and political development of the emerging powers, and thus their military capacity, is always fundamentally shaped by the constraints of operating within a system where the ultimate arbiters are the major imperialist powers. This does not mean, however, that those powers are always able to exercise a consistent degree of influence at the lower levels at the system. In fact, the overarching structuring feature of the current sub-imperial system in the Middle East for the past decade and a half has been the relative retreat of US power following its Pyrrhic victory over Saddam Hussein in Iraq in 2003. The catastrophe of US policy towards Iraq shows how processes in sub-imperial systems can accelerate trends at a global level. One of the beneficiaries of the relative decline of the US has been Russia, a bit player in economic terms, but endowed with the military and diplomatic legacy of the USSR, and increasingly assertive in geopolitical competition with the US and its allies in Eastern Europe and in Syria.

Table 1: Top five states in the Middle East (excluding North Africa, including Iran and Turkey) in terms of GDP (current $US), by decade

Source: World Bank.

|

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

2010 |

2016 |

|

Turkey |

Saudi Arabia |

Iraq |

Turkey |

Turkey |

Turkey |

|

Iran |

Iran |

Turkey |

Saudi Arabia |

Saudi Arabia |

Saudi Arabia |

|

Egypt |

Turkey |

Iran |

Israel |

Iran |

Iran |

|

Israel |

Iraq |

Saudi Arabia |

Iran |

United Arab Emirates |

United Arab Emirates |

|

Saudi Arabia |

United Arab Emirates |

Israel |

United Arab Emirates |

Israel |

Egypt |

The second structuring feature of the system, which is the deepening competition for regional hegemony between Iran and its allies on the one hand, and Saudi Arabia and its allies on the other, arises out of the conjuncture of processes at the “top” and “middle” levels of the global capitalist system. The rise of Saudi Arabia is a reflection of the emergence of a new centre of capital accumulation in the Gulf, while the re-emergence of Iran as a regional power is bound up with the gradual (and often halting) recovery of Iranian capitalism from catastrophic defeat in the war with Iraq in the 1980s. Two further points are important here. First, US military overreach in Iraq also has to be set in the context of a much longer-term process: the slow eclipse of US global economic dominance by the rise of China at the heart of an East Asian zone of capital accumulation.11 Secondly, the disaster that overtook the US in Iraq is an important reminder to take into account not only the agency of states or even of their ruling classes: the US defeated and destroyed Saddam and the ruling class of the Ba’thist state, but in the process unleashed an insurgency that drew its power from much wider layers of Iraqi society (including the working class Shi’a constituencies that formed the bedrock of Muqtada al-Sadr’s movement and which have tended towards Iraqi nationalist rather than pro-Iranian Shi’a Islamist politics).12

A third structuring feature is the role played by Israel in the sub-imperial architecture of the Middle East. This highly-militarised settler-colonial state disciplines the region’s inhabitants through its exemplary violence against the Palestinians on the one hand, and its overwhelming regional advantage in military technology on the other. The political and military neutralisation of Egypt was bound up with the earlier phase of Israel’s rise. Egypt’s defeat in 1967 was followed first by its acceptance of Washington’s neoliberal economic agenda and shortly afterwards by a peace treaty with Israel signed at Camp David in 1978. The Egyptian ruling class repeatedly missed opportunities to move to a more advanced phase of industrial development, and the vast flows of military aid were designed to guarantee the Egyptian Army’s role as internal gendarme rather than regional hegemon. By contrast, Israel has been propelled into the ranks of “developed” countries, underpinning a mutually beneficial economic and military partnership between the Israeli and US ruling classes.

Iran’s role as a regional power could also be read as an element of continuity from previous eras, when the Pahlavi dynasty formed one of the “twin pillars” of US hegemony in the Middle East. Of course, the 1979 revolution abruptly removed Iran from the US sphere of influence, helping to explain why Israel has remained so critical to the defence of US interests. The other “pillar”, according to the Nixon Doctrine, was Saudi Arabia, which is only now belatedly coming of age as a sub-imperial power in its own right.

Saudi Arabia and the rise of Gulf capital

Saudi Arabia’s graduation over the last few years from wielding soft to hard power externally has been abrupt. Since 2015, the kingdom has played a crucial role in the humanitarian catastrophe that has engulfed Yemen as a result of an intense Saudi bombing campaign, following an energetic mobilisation in the service of regional counter-revolution in 2011: invading Bahrain to crush the emerging mass protest movement in March 2011, and bankrolling the military coup led by Abdel-Fattah el-Sisi in Egypt in July 2013. This new role as a sub-imperial power is rooted in longer-term processes of transformation in the country’s economy and that of the Gulf region as a whole. In fact, as Adam Hanieh has stressed, the formation of a Khaleeji (Gulf) capitalist class spanning the members of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) has been a crucial factor in the development of an independent centre of capital accumulation in the Gulf over the past four decades.13 Nevertheless, we will concentrate here on Saudi Arabia as the pivotal component of Gulf capital in terms of the size of its economy, population and the current ambitions of its leaders to translate capitalist development into military power.14

The 1970s “oil shock” of precipitous price rises is often cited as a turning point in the political economy of energy in the region. However, the establishment of state control over upstream oil production marked a more important and permanent shift in the relationship between the state and international and local capital. In the case of Saudi Arabia, the takeover of upstream production took place in the early 1980s, and laid the basis for the development of a Saudi capitalist class which focussed its activities on the downstream oil industry (particularly petrochemicals), energy intensive sectors such as aluminium, steel and cement production, construction, import and re-export trade, massive retail projects in the form of hypermarkets and shopping malls, and finance.15

The interwoven processes of capital accumulation and class formation in the Gulf were shaped by and contributed to the neoliberal turn in the world economy. They helped to cement US hegemony by ensuring oil markets operate in dollars, recycled the same petrodollars through European and US banks allowing their conversion into new forms of debt bondage for the Global South, and accelerated trends towards the financialisation of capital across the system.16

The role of relations with the US ruling class in the emergence of Gulf capital are more complex than might first appear. Characterising Saudi capital as simply an extension of US capital is clearly wrong. Rather, the two capitals are locked into a relationship which is structured by the contradiction between the inevitability of competition in oil production, and the ability of the US pre-emptively to contain and manage this competition in its favour by virtue of being the more developed of the two and the military guarantor of the Saudi state. US policy towards Saudi Arabia was of course initially based on the logic of competition with an older imperialism, that of Britain. However, since the 1970s the underlying trajectory of US policy has been to nurture the development of Saudi Arabia as a subordinate capitalist ally. The combination of revolution in Iran and the outcome of the Iran-Iraq war threw the policy off balance, leading to the establishment of a massive direct US military presence in the Gulf, including the opening of US bases in Saudi Arabia for the first time after 1991.17 This triggered the first major political challenge to the ruling family from within Saudi Arabian society and, of course, eventual blowback in the form of the Al Qaeda attacks on the US itself ten years later.

Efforts by the Saudi ruling class to develop new strategies to cope with these changes appeared to have congealed to a certain extent in the person and policies of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. “MbS”, as he likes to be known, has shot to global fame since his appointment in 2017. He is credited with launching an “anti-corruption” drive that conveniently unseated or demoted rival relatives, articulating a “vision” for diversifying the Saudi economy away from dependence on oil, and overturning the ban on women driving.18 As minister of defence he has overseen Saudi Arabia’s military intervention in Yemen—which has proved catastrophic for the Yemeni people leaving the majority of the country dependent on humanitarian aid, ravaged by malnutrition and cholera. A purge of the Saudi army’s leadership in March this year underscored how Bin Salman is driving through changes in personnel in alignment with his overall strategy of economic diversification. The announcement of the replacement of the chief of staff and the heads of Saudi ground and air forces coincided with the launch of policies designed to favour the development of a domestic Saudi arms industry in partnership with international military capital.19 Meanwhile, Bin Salman’s energetic championing of economic reforms in the neoliberal mould, including changes to the legal system, business licensing and regulation, has won approval from the IMF.20

Israel: digital militarism embraces Christian Zionism

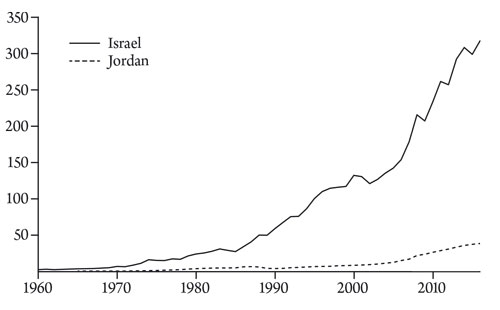

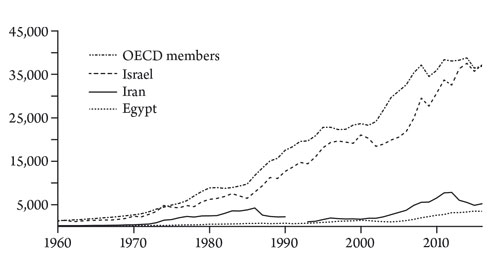

Israel has long played a crucial role in the dynamics of imperialism in the Middle East, even though its relationship with the major imperialist powers has changed in character over the decades. The Zionist project was incubated by the British Empire, but following the creation of the state of Israel in 1948, the US has assumed the role of imperialist sponsor. In the 70 years since Israel’s creation, US economic and military aid has totalled more than $131 billion at current prices.21 Direct economic aid, which played a crucial role in keeping the Israeli economy afloat in the face of hyperinflation and soaring military spending after near defeat in the 1973 war with Egypt and Syria, has been phased out. Meanwhile, Israel’s overall GDP and GDP per capita have also grown significantly (see figures 1 and 2), and the emergence of a new high-tech sector, which attracts around 15 percent of the world’s venture capital investment in cyber-security, has encouraged the rebranding of Israel as a “start-up nation”, which can jack straight into the booming global “digital economy”.22

Figure 1: GDP of Israel and Jordan (current US$ billions)

Source: World Bank.

Figure 2: GDP per capita (current US$)

Source: World Bank.

This has all taken place in the context of intensifying US-Israeli military cooperation. US military aid is designed to maintain Israel’s “Qualitative Military Edge” (QME), over its regional rivals. Since 2008 US arms sales to other countries in the region cannot be agreed on unless the government can prove they will not adversely affect Israel.23 As table 2 illustrates, the total value of the huge, long-term grants represented by successive Memoranda of Understanding (MoU) has been rising steadily over the course of several alternations between Democrat and Republican incumbents in the White House. A significant portion of this military aid has been provided in the form of co-production agreements, such as the 2014 deal which saw US manufacturers and Israeli military industries agree to work together to develop the Iron Dome rocket defence system.

Table 2: US-Israel Memoranda of Understanding

Source: Sharp, 2018.

|

Date of MoU operation |

Presidential sign-off |

Total value |

|

1999-2008 |

Bill Clinton |

$26.7 billion |

|

2009-2018 |

George W Bush |

$30 billion |

|

2019-2028 |

Barack Obama |

$38 billion |

Meanwhile, new labour migration policies in place since the early 1990s, following the 1987 Palestinian Intifada, have replaced Palestinian day labourers from the Occupied Territories with foreign workers from developing countries in sectors such as agriculture, construction and care-giving services. During the 1990s the number of non-Palestinian non-citizen workers overtook the total number of Palestinians who had ever worked in Israel put together.24 Meanwhile, the Oslo “peace process” and the creation of the Palestinian Authority under the leadership of Yasser Arafat, created a new apparatus of Palestinian officials in direct collaboration with the Israeli state, which colluded in the emergence of a shrunken Palestinian entity, entirely dominated by Israel both economically and militarily.

The US policy of increasing military support to Israel has gathered momentum for several decades. Even the decision to move the US embassy to Jerusalem was originally passed by the Republican-dominated US Congress in 1995, although Clinton and his successors signed six-month waivers delaying the implementation of the law. Trump’s ascendancy has brought several trends into closer alignment than before, intensifying pressures for Palestinian surrender. The first of these is the unholy marriage of convenience between US Evangelicals and the Zionist right. Trump and Benjamin Netanyahu have even shared a political patron: casino magnate Sheldon Adelson.25 Trump and the advisers currently running US Middle East policy (the president’s son-in-law Jared Kushner, US ambassador to the UN Nikki Haley, and his lawyer Jason Greenblatt, now adviser on Israel) have pushed through policies that are music to the ears of the Israeli right, including cuts to US funding for UNRWA, the UN agency which provides education and health services to hundreds of thousands of registered Palestinian refugees across the region.

Trump’s claims to be able to secure the “ultimate deal” to end the Israeli-Palestinian conflict need to be set in this wider context. The new embassy opening and the attack on UNRWA’s funding can both be read as pre-emptive moves to deal with two troubling “final-status” issues which the US ruling class now appears to want to resolve in Israel’s favour, with the acquiescence of Saudi Arabia and the Gulf: the question of sovereignty over Jerusalem and the right of return for Palestinian refugees. The mechanisms for achieving this in the short term involve both sticks and carrots; or rather live ammunition fired into crowds of unarmed Palestinian protesters and rocket barrages against supposed Iranian targets in Syria on the one hand, and the prospect of a slice of the profits of reconstructing battered Gaza for those in Fatah who are willing to play along.

Meetings in Brussels earlier this year provide a window into the ways that drinking water and electricity for Gaza’s residents are also being used as bargaining chips in this process. Israeli representatives presented a $1 billion plan for the reconstruction of Gaza, involving desalination plants, new electricity infrastructure, a gas pipeline and an upgrading of the industrial zone at the Erez Crossing.26 The pre-condition for ending the siege and beginning rebuilding is the removal of Hamas from power and the re-establishment of Palestinian Authority control over Gaza, a process which has been accelerating since the Saudi-led blockade of Qatar (which began in June 2017) underscored the Islamist movement’s lack of allies at a regional level.27

Iran: the reawakening of a regional power?

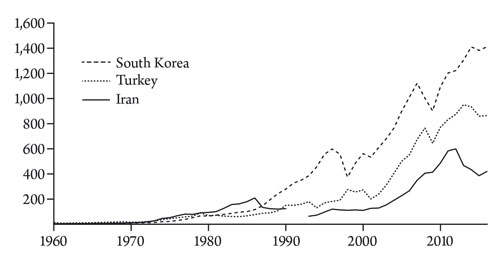

Iran has long been an important player in the political economy of the region. It was the discovery of oil there in 1908 that triggered the race to carve up the Middle East’s oil reserves between the European colonial powers, with Britain taking the leading role in staking a claim to Iran’s own oil fields. However, in contrast to the Gulf, agriculture, through the production of crops for export such as cotton, has also played a crucial role in integrating Iran into the global capitalist economy. As capitalism matured on a global scale, Iran appeared to possess many of the elements that could propel its economy into the next stage of development. Measured in terms of total GDP, and in terms of GDP per capita, in 1970 it would have been difficult to predict where Iran, its neighbour Turkey, or South Korea, a country with a comparably sized population which was then at a relatively similar stage of economic development, would end up in global rankings (figure 3).

According to the narratives of Western policymakers and mainstream academia, it was the overthrow of the monarchy in the revolution of 1979, and the subsequent shift towards state capitalist policies (in apparent defiance of global trends towards neoliberalism) that explain why Iran failed to follow the same trajectory as Korea.28 However, it was the struggle to survive, not ideological conviction, that drove the leadership of the Islamic Republic down a road of relatively autarchic state capitalist development in the 1980s, as the US sought to reverse the defeat it had suffered at the hands of a popular revolution by intervening to support Iraq against Iran in the war between 1980 and 1988.29 Seen through the relatively crude lens of the GDP data in figure 3, the moment at which Iran’s economic trajectory visibly shifted was 1986, and it was during the following year that Korea’s GDP and GDP per capita overtook Iran’s for the first time.

Figure 3: GDP of South Korea, Turkey and Iran (current US$ billions)

Source: World Bank.

Since the mid-1980s, Iran’s economy has seen a slow recovery across different phases of state policy directed by the new bourgeoisie which developed in the intense, hot-house period of relative autarchy imposed by the war with Iraq and by US hostility. As Peyman Jafari has noted, the post-revolutionary period remains crucially important in shaping Iranian capitalism today.30 The state capitalist war economy of that era gave birth to the bonyads, the massive state “foundations” that organised the distribution of resources and services to the urban and rural poor, helping to build a social base for the new regime as well as contributing to the ideological mobilisation necessary for the war effort.

Subsequent periods of neoliberal reform have not lessened the importance of the bonyads to the economy, nor to the state. Instead they have been integrated into a hybrid form of “really existing neoliberalism” that combines features of both neoliberalism and state capitalism.31 Iran’s longer-term trajectory of economic development is characterised by the underlying contradictions between potential economic strength and the geopolitical reality of the isolation and vulnerability of the Iranian ruling class. Time and again over the past 40 years, Iran’s rulers have been reminded of this by geopolitical shocks which have temporarily reshaped the economy. The most recent of these was the rapid reversal in the strong growth of the 2000s following the imposition of sanctions in 2011-2. GDP took a strong downturn as Iran lost its export markets in Europe.

Yet the Iranian ruling class has also been the unintended beneficiary of both the success and failure of US policy in Iraq. The military defeat of Saddam Hussein in 1991, followed by sanctions and finally the overthrow of his regime by US forces in 2003, removed the threat posed to Iran from a belligerent neighbour. The Iranian regime also benefited from long-standing relations with the former Iraqi Shi’a Islamist opposition groups such as the Da’wa Party and the Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution in Iraq, which ended up dominating the sectarian political system fostered by the US. These factors saw Iranian influence within Iraq began to grow during the late 2000s.32 US failures on the battlefield also opened the door to the expansion of Iranian military influence. The much-vaunted troop “surge” of 2006-8 (which essentially saw US forces reconquering the country) prepared the ground for the catastrophic loss of Mosul and much of northwestern Iraq to ISIS in 2014.33 Iran’s military influence in Iraq has largely been channelled through the development of the various sectarian paramilitary forces associated with Shi’a Islamist political parties.

The US ruling class has pursued alternating approaches to relations with Iran (albeit within a general perspective of hostility and suspicion). The agreement over Iran’s nuclear programme steered to completion by Barack Obama in 2015 was based on the assumption that the US could make tacit common cause with elements in the Iranian ruling class, eventually offering them a route back into the global market with the US’s blessing (and of course on the US’s terms). Trump’s abrupt withdrawal from the agreement is based on the “risky bet” (as the New York Times put it), that Iran’s ruling class will not have the economic muscle and political will to carry through the development of nuclear weapons (and if it does then the military capabilities of the US itself and its regional allies Israel and Saudi Arabia will be adequate to neutralise the threat).34

Turkey’s economic miracle and geopolitical predicament

Over the past three decades, Turkey’s economy has emerged as the largest in the region, pulling comfortably ahead of Saudi Arabia since 2000 despite having to import 90 percent of its oil and gas. Growth has been driven by the expansion of manufacturing, with smaller industrial producers, particularly those based in the provinces rather than the traditional “big business” sector based in Ankara and Istanbul, benefiting the most. The expansion of provincial and small-medium industrial capital is one of the factors explaining the ability of the ruling AKP under Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s leadership to withstand the pressures from sections of the Turkish state and big business which object to the AKP’s Islamist politics and have consistently organised to curtail access by those with an Islamist worldview to the levers of power. The AKP’s electoral success during the 2000s is also likely to be related to Turkey’s strong economic growth with the percentage of the population living below the national poverty line declining from 28.8 percent in 2003 to 1.6 percent in 2014.35 Such statistics hide continued social inequality and problems of low productivity in more “informal” sectors of manufacturing. But the idea that an Islamist government has delivered “prosperity” for a relatively wide section of the population helps explain how the deeply contradictory social base of the AKP has welded together working class and poor constituencies with an increasingly assertive and wealthy section of Turkish capital organised through the Independent Industrialists’ and Businessmen’s Association (MÜSİAD).

The fate of the Turkish “economic miracle” of the past decade and a half remains inextricably linked to the dynamics of geopolitical competition. Turkey’s position as the gateway to the world for the oil of northern Iraq means that the country’s ruling class has much at stake in the question of who governs Kirkuk and Mosul (and both cities have become important export markets for Turkish goods). Turkey’s eastern border also connects with Iran, which over the last year has overtaken Iraq as the largest crude oil supplier to Turkey.36

The repression of the Kurdish population on the Turkish side of the border has long been a complicating factor in Turkey’s relations with Iraq. During the 2000s the Turkish ruling class pursued a long-term peace process designed to end the insurgency led by the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) within Turkey, while at the same time restricting the PKK’s ability to use neighbouring countries as either a military hinterland or a source of diplomatic and political support. This was one reason behind the Turkish government’s strong relationship with Bashar al-Assad’s regime in Syria (the opening of Syrian markets to Turkish exports was another), and the surprisingly cordial relations between Turkey and the Kurdistan Regional Government in Erbil (which is led by the Kurdistan Democratic Party, no friend of the PKK).

The unravelling of Syria in a multi-sided conflict which spiralled out of the military onslaught by the Assad regime against the popular uprising in 2011, fundamentally altered the geopolitical landscape on Turkey’s southern and eastern borders. It left Turkey hosting 56 percent of the Syrian refugees who have fled the country. The Assad regime switched from friend to foe almost overnight, a new Kurdish entity in the Rojava region emerged between Turkey and Syria, and the military forces of the Syrian PYD party (which is allied to the PKK, unlike the KDP in Iraq) began to play a crucial role as ground troops for the US in its efforts to destroy ISIS. These developments lie behind the Turkish government’s abrupt abandonment of the peace process with the PKK and the resumption of war in the eastern provinces. Turkish troops recently invaded Afrin in northern Syria, driving thousands of Kurdish residents into exile in an attempt to prevent the canton linking up with the other areas which make up the Rojava region.37

Syria: from civil war to regional war?

The arena where the dynamics of competition between global and regional powers currently intersect in the most frightening manner is Syria. Contending military forces from every “level” of the global system are currently active in multiple conflicts there. The US, which has deployed 2,000 ground troops in Syria since 2015, is reported to be planning to build an “open-ended military presence in Syria”.38 US, UK and French airforces and naval vessels intermittently bombard targets in Syria, while Russia’s air power is generally agreed to have shifted the military balance in the war in favour of the Assad regime. Russia has established a new base at Hmeymim aerodrome and renewed long-term agreements on the use of its existing naval facilities in Tartus.39 Regional powers too are active in Syria’s various military conflicts, with Iran supporting Assad and entrenching both a direct military presence and supporting its ally, the Lebanese movement Hizbollah. After the invasion of Afrin, the Turkish government reacted angrily to an announcement by the US, its NATO ally, about plans to train a “border force” underpinned by the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF).40 Finally, there are multiple, competing military actors at local level, which can be labelled as “Kurdish”, “Sunni jihadist”, “opposition” or “pro-government” (including regular army units and paramilitary organisations), in a desperate attempt to make sense of the kaleidoscope of shifting coalitions and ever-changing frontlines.

There are many reasons why the war which Assad started against the popular uprising of 2011 spiralled into a conflict which has not only ripped Syria apart but has also sent shockwaves through the regional and global imperial systems. There is not space here to properly examine these dynamics, but we can at least sketch out three themes which stand out in these entangled processes. One of these is the impact of the disaster which overtook neighbouring Iraq. There are multiple ways in which the effect of the successive cycles of war, siege, invasion, occupation, insurgency and sectarian conflict in Iraq affected Syria, including the fragmentation of state authority over their shared border, massive movements of refugees from Iraq to Syria, the intervention of Iraqi paramilitary organisations in the conflicts in Syria (including not only Sunni groups such as ISIS, but also Shi’a sectarian militias recruited by the Assad regime). The collapse of the Iraqi government’s authority in the majority-Kurdish areas of the north led to the emergence of a de facto independent Kurdish statelet accelerating the push towards regional autonomy in Kurdish areas of Syria.

These factors interacted, however, with the counter-revolutionary strategy pursued by the Assad regime. As has been argued in more detail elsewhere, Assad’s decision to treat areas that rebelled against him in 2011 as “enemy territory”, subjecting them to aerial bombardment and siege, had profound consequences.41 The regime’s survival strategy was also predicated on its ability to weaponise sectarianism—posing as the protector of minorities against Sunni jihadism, while mobilising its own allies on a sectarian basis and carrying out or enabling sectarian atrocities calculated to fracture the cross-sectarian unity forged in the early days of the uprising. Because there was an apparently seamless transition from uprising to armed insurgency and eventually civil war it is often forgotten that the military hegemony of the Sunni jihadist forces on the anti-government side was predicated on the defeat of the popular protest movement over the course of 2011. The rise of ISIS and its seizure of Raqqa and Mosul came later still, reaching its height in 2014-5. The inability of ISIS’s leaders to stabilise their military gains, partly because their ideological rigidity got in the way of the more pragmatic aspects of state-building, has also opened a new phase in the cycle of apparently endless war (although it is too early to write off ISIS altogether as a military force, as Patrick Cockburn recently warned).42 Moreover, as the slow but remorseless process of the Assad regime’s elimination of the major remaining opposition-held territories grinds on, the identity of likely winners and losers at a regional level is becoming clearer.

Behind the smokescreen of claim and counter-claim, it is clear that Iran’s military and political influence has dramatically expanded in Iraq and Syria. Iran’s ally Hizbollah has played a major military role in supporting Assad’s offensives against opposition forces. Iraqi Shi’a paramilitary groups supported by Iran mobilised on behalf of the Assad regime. Iranian influence is said to be “embedded” deeply in the Syrian state, through the role of advisers who have built up powerful pro-government paramilitary forces.43 The faction of Iranian capital most closely linked with the state institutions, such as the Revolutionary Guards, leading the policy of intervention in Iraq and Syria, also hopes to benefit from the post-war reconstruction.44

The possibility that the outcome of the Syrian civil war will be to strengthen Iran’s position in the regional sub-imperial system is a major factor behind Trump’s withdrawal from the nuclear deal. A coordinated military and diplomatic offensive by Israel has combined repeated missile strikes on alleged “Iranian bases” inside Syria with a ratcheting-up of official propaganda highlighting the Iranian regime’s ambitions to regional hegemony and sponsorship of “terrorism”. Netanyahu has led the charge: holding a press conference exposing “secret” information about Iran’s alleged violation of the terms of the deal and energetically lobbying Trump to pull out.45 Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman has joined the chorus of condemnation of Iran, denouncing the Islamic republic from the same script.

Yet it is important not to overstate the Iranian resurgence. It was Vladimir Putin’s intervention that decisively altered the military course of the war, as Russia was driven by the logic of imperialist competition with the US both to defend an existing ally in the Assad regime, and to seize the opportunity to open a new arena for Russian military and diplomatic intervention. Moreover, it would be a mistake to assume that despite their shared commitment to ensuring the Assad regime’s survival, that the pressures acting on Russia and Iran in relation to Syria are identical. Recent Israeli missile attacks may be an attempt to send a signal that in return for restraining and managing the Iranian presence in Syria, Russia will enjoy the opportunity to stabilise its “achievements” which could be put at risk by a regional conflagration involving Israel and Iran.46

Indeed, the modest revival of Iran’s geopolitical fortunes thanks to catastrophic miscalculations by the US, needs to be put in the wider context of a sub-imperial system where Israel and Saudi Arabia are aligned more closely than in the past. Equally importantly, we have to take into account the ways in which the dynamics of sub-imperial competition are affected by competition between the major imperialist powers. As we have explored here, the sub-imperial roles of both Israel and Saudi Arabia are contingent on continued US military and economic support, even if the character of the relationship between them has changed. US warplanes and aircraft carriers are still the ultimate guarantor of the survival of the House of Sa’ud in 2018, just as they were in 1990. Yet the military adventurism of Mohamed bin Salman in Yemen, combined with the leading role played by the Saudi ruling class in the counter-revolution in Egypt, suggests that Saudi Arabia’s rulers are no longer content simply to leave military decision-making to others, but are developing increasingly itchy trigger fingers.

Thus, the relative retreat of US power in the Middle East following the long agony of Iraq, has not, of its own accord, led to the deceleration of imperialist competition, but rather to the opposite as the ambitions of the regional powers (Iran, Saudi Arabia, Israel and Turkey) and rival major powers (Russia) expanded to fill the gap. It stands as a reminder, if one were ever needed, that imperialism is not bound up with any specific state or group of states but is deeply rooted in the process of capital accumulation and will only be finally eradicated with the end of capitalism itself. Faced with social destruction on the scale experienced in Syria and Iraq, or the horrifying prospect of war between nuclear-armed states, it can feel as if the levers of history are all in the hands of the powerful. Yet recent waves of strikes in Iran, protests over soaring public transport prices in Egypt, popular mobilisations across the sectarian divide in Iraq against corruption and mass demonstrations over IMF-backed austerity measures in Jordan should all remind us that the rulers of the Middle East ignore questions of class at their peril. The question of how to fuse anti-imperialist and anti-capitalist resistance from within and below in the Middle East, despite the defeats and setbacks since 2011, remains a critical issue for revolutionary socialists.

Anne Alexander is the co-author, with Mostafa Bassiouny, of Bread, Freedom, Social Justice: Workers and the Egyptian Revolution (Zed, 2014). She is a founder member of MENA Solidarity Network, the co-editor of Middle East Solidarity magazine and a member of the University and College Union.

Notes

1 Callinicos, 2018, p9. Thanks to Alex Callinicos, Jad Bouharoun, Phil Marfleet and John Rose for comments on the draft of this article.

2 Margulies, 2018.

3 Sanchez, 2018a.

4 Smith, 2018.

5 On the relationship between states and capitals, see Harman, 1991. On imperialism see Bukharin, 1967, Callinicos, Rees, Haynes and Harman, 1994 and Callinicos, 2009.

6 Callinicos, 2009, p185.

7 While there is not space here to explore these in detail, the debates on the left over how to understand the dynamics of imperialism in the Middle East during the Iran-Iraq war of the 1980s are a useful reference point for discussions about sub-imperialism in the region today. See Callinicos, 1988 for an overview of the position taken by writers in the tradition of this journal at the time.

8 Callinicos, 2009, p166.

9 See Callinicos, 2009 for a detailed discussion of this point.

10 The analysis developed in this article is focused on the dynamics of imperialism in the majority Arabic-speaking states of the Gulf, the Levant and Egypt (recognising that some of the states of the Levant have significant Kurdish-speaking minorities), with the addition of Iran, Turkey and Israel. Lack of space has precluded discussion of North Africa/the Maghreb.

11 Callinicos, 2018.

12 See Alexander and Assaf, 2005a and 2005b on the early phases of this process. See also Herring and Rangwala, 2006.

13 Hanieh, 2011.

14 This is not to say that the attempts by Saudi Arabia’s rulers to assert their leadership over the rest of the Gulf have always been successful. The blockade of Qatar initiated in June 2017 is a case in point. Rather than subduing Qatar, after a year of economic and diplomatic embargo, the Qatari ruling class appears to have deepened strategic links with China and Iran rather than collapsing under the pressure of its larger neighbours—See for example Chowdhury, 2018 on relations with China.

15 Hanieh, 2011.

16 Hanieh, 2011, p47.

17 Smith, 1991.

18 Stancati and Malsin, 2018.

19 Carey, 2018.

20 Al-Baqmi, 2018.

21 Thomas, 2017.

22 Economist, 2017.

23 Thomas, 2017.

24 Population and Immigration Authority, 2016, p11.

25 Clifton, 2017.

26 Landau, 2018; Chair of the Ad Hoc Liaison Committee, 2018.

27 Williams, 2018.

28 Maloney, 2015.

29 Callinicos, 1988.

30 Jafari, 2009.

31 Jafari, 2009; Afary, 2017.

32 Nader, 2015.

33 Alexander, 2016.

34 Sanger and Kirkpatrick, 2018.

35 OECD, 2016, p18.

36 Tiryakioglu, 2018.

37 Margulies, 2018.

38 BBC News, 2018.

39 Tass, 2017.

40 BBC News, 2018.

41 Alexander and Bouharoun, 2016.

42 Cockburn, 2018.

43 See Sinjab, 2017 for an example of analysis in this vein.

44 Blanche, 2017.

45 Sanger and Kirkpatrick, 2018.

46 Sanchez, 2018b.

References