Life on earth is arguably the most extraordinary phenomenon in the perceivable universe. And, among living things, 21st century humans are uniquely possessed with the means to appreciate this remarkable occurrence. Scientifically, for example, we can consider the sheer number and diversity of species in existence today. The Catalogue of Life1 project lists 1.58 million species identified to date, and the final tally looks likely to fall between 2 and 8 million.2 It is also worth considering that our geological moment holds the highest levels of species diversity in the Earth’s history, and that extant species probably represent only 1 percent of those that have ever lived on Earth—a total of between 200 and 800 million species.

This richness of life on Earth is described as biodiversity. At one level, this term applies to the number of species and genetic diversity within species. But it also includes the aggregated interactions of individual organisms and species through the multilayered food webs and trophic levels that we describe, in turn, as ecology and ecosystems. The outputs of these units and interactions of biodiversity define and reflect the world in which we live. Thus viewed, we can describe biodiversity as nothing less than living nature itself.

Beyond the numbers it is worth encountering some of the curious wonders of our planet’s biodiversity at the individual species level. Take Australia’s gastric-brooding frog Rheobatrachus silus. Discovered in the babbling brooks of south eastern Queensland in 1973, the female frog of this species has the unique ability to host its own offspring through all stages of metamorphosis—from egg spawn to tadpole to juvenile—within its own digestive system. It effectively turns its stomach into a brooding chamber and gives birth to its young through its mouth, returning the stomach to digestive duties a few days later. For another example, consider the Arctic cod Boreogadus saida. This fish lives at oceanic depths of 900 metres within 70 miles of the North Pole. The water temperatures within its habitat hover around 0°C—conditions that would ordinarily freeze the biological tissues and fluids of an organism. The Arctic cod survives these extreme temperatures by producing “antifreeze” proteins that reduce the freezing temperatures of its own body fluids. The physical, chemical and biological mechanisms necessary to undertake these functions, and the route through which these evolutionary strategies must have developed, are testimony to the creative force inherent within biological evolution.

Aside from the science, biodiversity also plays an inspirational role in our lives in other ways—through our culture, art, poetry and language, for example. Within our own individual consciousness, our fellow life forms are used as one of the tap-wells of human imagination, providing us with a rich seam of metaphors with which to explore our cognitive horizons, and sensory alternatives to contrast with our own human frailties. In our social context, connection with other living forms helps us a little to cope with alienation—whether this entails the keeping of pets and houseplants, or pausing to feed the pigeons on a lunch break.

From the perspective of human livelihoods, however, the most significant intersection between ourselves and wider biodiversity revolves around our dialectical interrelationship with life as the chief material means through which we feed, clothe and shelter ourselves.

Biodiversity’s explicit or implicit value to humanity is multifaceted and extends across the full spectrum of our life experience. But today, in our relationship with Earth’s biodiversity, we are faced with a contradiction between this grandeur of life and the capitalist social conditions under which it and we are being subjugated. At its sharpest point of conflict, this contradiction is proving fundamentally and irreversibly destructive. A decade on from the scientific discovery of Australia’s gastric brooding frog the species was declared extinct—probably wiped out through habitat loss (deforestation) and the globalised spread of the chytrid fungus.3 The threat of similar extinction now hangs over a third of the world’s remaining amphibian species. The Arctic cod, meanwhile, faces an uncertain future under climate change as fish species from temperate latitudes expand their ranges northwards into the warming Arctic waters. These small examples illustrate the profoundly serious outcomes of today’s conflict between human society and life itself—biodiversity loss and extinction.

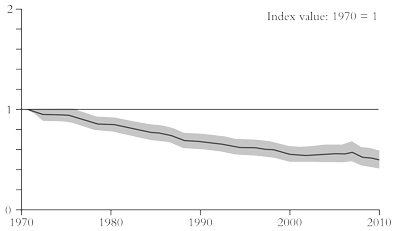

Post-war rates of biodiversity loss have been without parallel in human history, and there has been a tangible worsening of this situation over the last 40 years. In 2014 the latest figures were released from WWF’s Living Planet Index (LPI) programme.4 This index calculates the fortunes and population trends in 10,380 populations of over 3,038 representative vertebrate species (fishes, amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals) across a wide global network. Alarmingly, the 2014 global LPI shows a statistically weighted decline of 52 percent between 1970 and 2010 (figure 1); a halving in the size of the surveyed vertebrate populations over slightly more than one human generation.

Figure 1: Global living planet index (with confidence limits)

Source: WWF, 2014

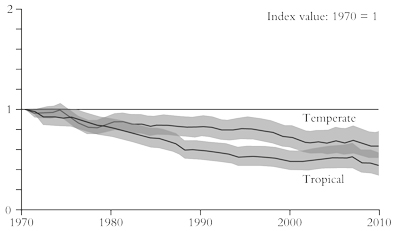

While the global LPI trends are alarming enough the disaggregated patterns are even more disturbing. The LPI for temperate latitudes, where environmental regulations are strongest, reveals a decline of 36 percent between 1970 and 2010. But the tropics fared worse with an LPI decline of 56 percent over the same period (figure 2).

Figure 2: Temperate and tropical living planet indexes (with confidence limits)

Source: WWF, 2014

At lower spatial scales, the declines are even more extreme. For freshwater habitats, the decline was recorded at 76 percent between 1970 and 2010. When broken down into biogeographical regions the steepest declines in LPI over the same period were in the neotropical region (South America) at 83 percent, and the Indo-Pacific region (South East Asia and Australasia) with a 67 percent decline.

In terms of direct causality the LPI programme reports 45 percent of the decline in biodiversity as a product of habitat degradation and loss, 37 percent as due to direct exploitation (hunting, fishing and harvesting), and the remaining 18 percent as resulting from climate change, pollution, invasive species and disease.

The rapidity of this decline in biodiversity is dizzying to consider. Across the entire known geological record there are no such precedents to be found. The present rates of biodiversity loss outstrip the five ominous mass extinction records that can be detected in the Earth’s geological history—the last of which witnessed the end of the dinosaurs 65 million years ago. The most recent survey of evidence suggests that, for vertebrates, extinction rates between the years 1500 and 1980 were 24 to 85 times higher than those of the end of the Cretaceous 65 million years ago. Since 1980, under neoliberalism, the rates of loss have risen to 71 to 297 times those of this last geological mass extinction event.5 If we make the dreadful but potentially accurate assumption that the species groups currently listed as endangered or vulnerable are, in effect, already geologically extinct, then the magnitude of the biodiversity crisis comes fully into view:

Recent vertebrate extinction moved forward 24 to 18,500 times faster since 1500 than during the Cretaceous mass extinction. The magnitude of extinction has exploded since 1980… These extreme values and the great speed with which vertebrate biodiversity is being decimated are comparable to the devastation of previous extinction events. If recent levels of extinction were to continue, the magnitude is sufficient to drive these groups extinct in less than a century.6

Sadly then, comparisons between today’s scale of biodiversity loss and those of previous mass extinctions are all too relevant. It has become common for many biodiversity conservationists to conclude that we are currently in the throes of a Sixth Extinction.7 This comparison was tested in the pages of the world’s leading international science journal, Nature, in 2011 using categories of extinction threat that have been laid down by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN):8

Even taking into account the difficulties of comparing the fossil and modern records, and applying conservative comparative methods that favour minimising the differences between fossil and modern extinction metrics, there are clear indications that losing species now in the “critically endangered” category would propel the world to a state of mass extinction that has previously been seen only five times in about 540 million years. Additional losses of species in the “endangered” and “vulnerable” categories could accomplish the sixth mass extinction in just a few centuries. It may be of particular concern that this extinction trajectory would play out under conditions that resemble the “perfect storm” that coincided with past mass extinctions: multiple, atypical high-intensity ecological stressors, including rapid, unusual climate change and highly elevated atmospheric CO2.

The huge difference between where we are now, and where we could easily be within a few generations, reveals the urgency of relieving the pressures that are pushing today’s species towards extinction.9

This “perfect storm” is reaching a crescendo and the possibility that we are living through a Sixth Extinction is quite literally an issue of deadly seriousness. It calls for urgent deciphering and amelioration of the causal factors. But this is not a crisis that can be analysed in isolation from human society, or as something that carries greater import over other societal crises. The reasons why have been stated simply by David Harvey: “All critical examinations of the [human] relation to nature are simultaneously critical examinations of society”.10 As socialists we should have little difficulty attending to this dialectical truism. But it is worth outlining the specific reasons why this radical approach is so important.

Firstly, we need to trace the fundamental causes of the biodiversity crisis, insofar as they can be detected, and set these within their relevant historical and social contexts. Secondly, this approach is politically vital because it helps us counter the fatalistic and misanthropic arguments—prevalent especially within Western environmentalism—that paint humanity as an inherent and historically consistent destructive force within nature. Thirdly, for the sake of existing and future generations, we need to understand the societal risks and ramifications of the biodiversity crisis. And, fourthly, we need to arm ourselves with the appropriate rational tools that can lead us, and Earth’s life, out of the crisis. This article will discuss the first two of these areas in detail, and comment briefly on the third and fourth considerations in conclusion.

Locating the biodiversity crisis

Today’s biodiversity crisis is a product of capitalism alone. This assertion is an important one to make for a number of reasons.

The most significant interrelationship between Earth’s biodiversity and human society occurs across the human food chain—agriculture and fisheries. At an overarching level, all pre-capitalist social formations—even where they caused ecological disruption and localised extinctions—depended on a functional dialectical interrelationship with biodiversity to maintain their means and modes of production; the productivity of their agricultural soil and wild food sources. That said, there is little doubt that our prehistoric ancestors, both before and after the neolithic agricultural revolution 10,000 years ago, would have pushed certain species to the brink and beyond. The global expansion of Homo sapiens in our pre-agricultural phase coincided with extinction of megafauna—animals over 50 kg—including iconic species such as the sabre-toothed tiger in the Americas, the woolly mammoth across northern latitudes and the moa in New Zealand. Whether or not these incidents resulted from the actions of our ancestors alone or the combined forces of human agency and climate change, the ecological changes that such events provoked would have been significant at local and regional levels. In many cases, however, the ecological roles of these large animals were subsequently taken up by human beings themselves as they pushed and pulled at local ecosystems to generate their own social metabolism through the controlled use of fire, shifting agriculture and the proactive management of woodlands, tundra and savannah.

In the intervening millennia between the neolithic agricultural revolution and the end of feudalism the ecological impact of human groups would have carried at least as many benefits for biodiversity as threats. This is because human society and culture formed one of the key dynamics within regional ecology. The patterns of biodiversity that emerged through the interplay between pre-capitalist societies and nature resulted in an ecological dynamic that enhanced biodiversity through the constant low-level intervention of rotational subsistence agriculture and habitat control for hunting. By keeping ecological niches open that would otherwise have closed through the natural process of ecological succession, human settlements created a diverse mosaic of habitats around themselves. This ecological pattern meant that biodiversity became increasingly embedded within anthropogenic systems and structures. And, because pre-capitalist social structures and cultures varied, so too did their attendant patterns of biodiversity.

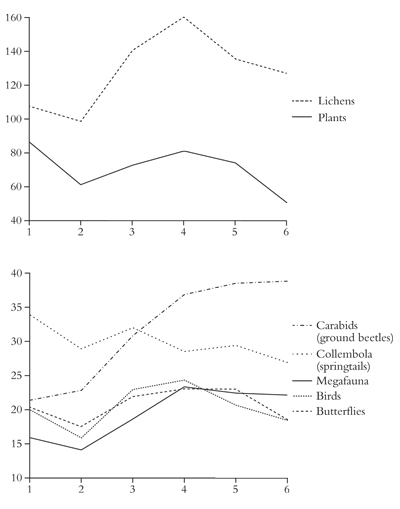

In Europe the types of extensive agriculture historically associated with low input farming and peasant land use appear to have been positively beneficial for biodiversity. Figure 3 indicates a peak in biodiversity for many taxa at these low intensity land use levels. For certain significant taxa the biodiversity level is higher even than that associated with the “unmanaged” conditions often presumed to replicate original “natural” ecology. This pattern explains why land abandonment is seen as a threat to biodiversity and why much of Europe’s conservation is geared towards replicating historic modes of agriculture through conservation grazing and the like.11

Figure 3: Average species richness of seven different taxa across a land-use gradient of sites from unmanaged forest (1) to intensive arable (6) in eight different countries in Europe

Source: Watt and others, 2007

From the 16th century, as capitalism entered the world stage, this diverse pattern of agricultural and semi-natural habitats became subject to the same disruption as those human societies that were initially touched, then subsumed, by an expanding global economy. This crucial juncture ushered in the fundamental tipping point in our interrelationship with the rest of life. The conjuncture of early capitalism and the shared evolutionary progress of human organisation “fused early modern states (and quasi state structures such as chartered trading companies) and markets and raised them to new levels of capacity and efficiency. These newly powerful institutions, acting in concert, intensified human impacts on the natural environment in nearly every region of the world”.12

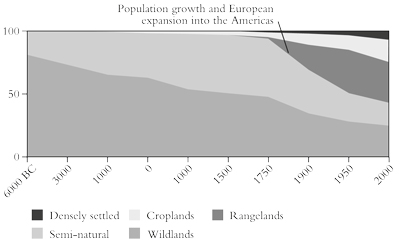

A recent historical assessment of anthropogenic changes to the Earth’s biosphere reveals the global significance of early capitalism—particularly at the birth-points of capitalist agriculture and urbanisation (figure 4).13

This graph also highlights the period from 1750 to 1900 as that in which human purchase on the biosphere rapidly accelerates. This expansionary phase is picked out by the author as being the consequence of “population growth and European expansion into the Americas”. There’s little doubt that these factors have been influential.14 However, the rapid rates of planetary subjugation to human influence from 1750 onwards are more accurately located in the rapid spread of capitalism following the industrial revolution and its application to imperialism/colonialism, global trade and early mechanised agriculture.

Figure 4: Transformation of the biosphere: Percentage of global ice-free land area

Source: Jones, 2011 (note that the x axis is not to scale)

Figure 4 also illustrates why conservationists’ efforts to push back the timeline of the Sixth Extinction to include pre-capitalist human history are difficult to justify. Tim Flannery, for instance, argues: “Since our emergence from Africa fifty thousand years ago, the sweep of human history has been a tale of destruction that has crippled one ecosystem after another”.15 The reasons why popular scientists such as Flannery proffer such historically dubious arguments will be discussed shortly. For now it is sufficient to counter by pointing out that the Sixth Extinction is a global event.

Before 1500—and more specifically before the industrial and agricultural revolutions of the 18th and 19th centuries—human society simply lacked the necessary technical ability and spatial reach to “cripple” ecosystems and threaten extinction at any significant geographical or geological scale. Pre-capitalist societies, in their quest to survive, manipulated biodiversity to the best of their abilities for sure—but their societal forms would still have been essentially bound by the material forces of nature. On this point above all, what the preceding graph highlights is the historical moment at which the development of industrial capitalism effectively allowed humanity to smash through the ceiling of so-called natural limits.

Industrial capitalism created the means by which humanity could initially liberate itself from nature. But by doing so on a finite planet, this could only be achieved through the displacement of biodiversity. The total percentage of the biosphere commanded wholly for human consumption rose from 10 percent in 1750, to roughly 60 percent by the end of the 20th century. By this time 50 percent of the biosphere had been diverted towards capitalist agriculture (croplands and rangelands). This figure represents the high water mark for agriculture since today pretty much all the land surface that can lend itself to farming has been commandeered.16

Convincing as this displacement pattern is, it is merely descriptive and it gives us little meaningful insight into why and how capitalism—and capitalist agriculture in particular—has given rise to the biodiversity crisis. If each pre-capitalist human society, driven by its social metabolism, had to forge its own relationship with biodiversity and its own ecological expression, the same must be true of capitalism. The vital task, then, is to identify the fundamental character of capitalist ecology.

The ecological anatomy of capitalism

Marx’s opening salvo in Capital provides the key to understanding capitalist ecology: “The wealth of societies in which the capitalist mode of production appears is as an immense collection of commodities”.17 This characteristic—commodity production—sets capitalism apart from all preceding social formations. As Joseph Choonara puts it:

Perhaps the most striking difference between capitalism and what came before it is what happens to the things that are produced. In earlier societies people worked mainly to produce goods for their own consumption, but capitalism is different… The goods produced under capitalism are not produced to meet immediate needs; they are produced to sell.18

At an abstract level then, the reason why capitalism creates the conditions for biodiversity loss is that non-human species and ecosystems that lie outside of the commodity production process simply fail to realise any meaningful valuation. This harsh logic applies not only to elements of biodiversity that fall completely outside of human instrumental utility, but also to those forms of biodiversity that have developed alongside and with other non-capitalist social formations such as subsistence or peasant agriculture. Recognition of the worthlessness—from a capitalist perspective—of non-commoditised biodiversity is a vitally important first step in understanding the Sixth Extinction. But this exclusionary principle does not act alone since other key characteristics of capitalism play their part.

First, insofar as it relates to global biodiversity, capitalist commodification operates across an incredibly narrow spectrum of life. The UN’s Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO) lists the dominant commodities that are produced and traded within global agriculture.19 The numbers (approximately 18 livestock species and 155 species of crops) are a drop in the ocean compared with the figures for global biodiversity. Indeed, even within this narrow range of commoditised species a parallel biodiversity crisis is unfolding as a diminishing number of varieties and breeds are selected to service global “market needs”, and the dictates of agro-industrial multinationals and supermarkets—often justified through the presumed tastes of consumers.

This narrow focus on a tiny number of usable units of the Earth’s biodiversity is no accident. It is, rather, a product of ruling class hegemony over the selection of commodities and access to their markets. Historically, most of the crop and livestock varieties that form the commodity backbone of our global agricultural economy were selected, adapted and utilised by prehistoric farmers. But increasingly their dominance within global agriculture depends on their ability to turn soil into profit for major agro-industrial multilateral corporations. The fact that we are faced with a biodiversity crisis suggests that capitalist ecology does not need to draw on the vast pool of ecological entities and functions available to it in nature. But if this is the case then it is reasonable to ask how it functions at all. As a social system capitalism may be dynamic, but it cannot produce ecological functions out of thin air to support its metabolism.

To understand how capitalism pulls off the illusion of ecological independence from nature we need to consider how capitalist agriculture relates to wider industry. Until the middle of the 20th century capitalist agriculture still depended to varying degrees on processes that worked in tandem with biodiversity. Farmholdings were often diverse and mixed-use and the levels of artificial, non-organic inputs were relatively low. Post-war capitalism—and the neoliberal phase in particular—has somehow broken the last of those links between living nature and agricultural production. In the process advanced capitalist agriculture has dramatically altered the ecology of the farmed environment to the detriment of biodiversity. The general reasons for this shift are highlighted by Miguel Altieri:

While the present capital and technology-intensive farming systems have been extremely productive and able to furnish low-cost food…the very nature of the agricultural structure and prevailing policies in a capitalist setting have led to [the present] environmental crisis by favouring large farm size, specialised production, crop monocultures and mechanisation. Today, as more and more farmers are integrated into international economies, the biological imperative of diversity disappears due to the use of many kinds of pesticides and artificial fertilisers, and specialised farms are rewarded by economies of scale.20

Capitalist ecology, as expressed through agriculture, arises through the systematic destruction of its natural base and the simultaneous attempt to create its own artificial ecosystem using the outputs of technology and wider industrial commodity production (eg inorganic pesticides and fertilisers). This tendency represents not just a break with nature and a further devaluing of biodiversity’s commodity potential, but a complete rejection of the practice of rational nutrient conservation and recycling that had underpinned agriculture since its birth in the Fertile Crescent 10,000 years ago.

The active dismantling of nutrient recycling practices by modern capitalist agriculture has given rise to the final key characteristic of its ecology. Capitalist ecology has become open-ended. Its waste outputs and surplus inputs are discharged into the environment as forms of atmospheric and water pollution. Its inputs are increasingly drawn from non-renewable and sensitive sources such as the world’s dwindling phosphate reserves in Western Sahara, and the medical antibiotics whose excessive use in beef herds contributes to the development of resistant strains of bacteria.

These characteristics of capitalist ecology—commodification, the industrial rise of artificial ecological inputs, monoculture development and regionalisation, resource exhaustion and waste creation—are driving us ever further away from nature and thereby hiding capitalism’s consequences for biodiversity from our collective view. It is tempting to conclude that the anatomy of capitalist ecology is actually anti-ecological. But it is probably more useful to describe it as ecologically dysfunctional.

Extinction: The misanthropic misdiagnosis

The trends in biodiversity loss revealed by the LPI point an accusatory finger at neoliberalism and the capitalist mode of production. The pattern of humanity’s history of biosphere domination likewise highlights the development of capitalism as the most significant trigger point for our global domination of earth’s biosphere. Capitalism itself drives the root causes for biodiversity loss through its emphasis on commodity production and its own ecological patterns that substitute artificial inputs in place of natural ecological functions.

Conservationists have occasionally attempted to deal explicitly with these links between capitalism and biodiversity loss. The most radical critiques of capitalism and its impact on biodiversity were voiced at the high point of the anti-capitalist movement at the turn of the century. Around this time there were calls from environmental NGOs for the impact of poverty, inequality and multinational corporations to be recognised as root drivers of biodiversity loss.21 A substantial World Wildlife Fund (WWF) report from this time argued:

Only by exploring and understanding the socioeconomic factors at various levels—local, regional, national and international—that drive people to degrade the natural environment will we be able to change this behaviour. To find more effective conservation solutions, we must step back and look at the complex set of influences on local resource use that constitute the root causes of biodiversity loss.22

In contrast, today’s calls from neoliberal environmental economists for the commodification of nature,23 and the definition of biodiversity as “natural capital” by conservation NGOs such as WWF24 can be interpreted as a rather desperate capitulation towards capitalism in the hope that global corporations and nation states will save the day by establishing formal markets in “ecosystem services”.25

Away from these mixed efforts, the prevailing narrative around the causes of the Sixth Extinction is dominated by scientists and authors who seek explanations in our human biology rather than our societal anatomy. In general, these arguments follow the standard contours of biological determinism. This school of thought locates its explanations for patterns in human behaviour, societies and cultures within human biology, DNA and biological evolution. Here, as with all the other social ills such as war and greed, our supposed “ecocidal” tendencies are presented as unshakable genetic constituents of our species being.26 Elizabeth Kolbert’s position is typical: “Though it might be nice to imagine there once was a time when man lived in harmony with nature, it’s not clear that he ever really did”.27

Examples of this approach dominate the “popular science” shelves of today’s bookshops through works by leading public scientists such as Stewart Brand, James Lovelock, Jared Diamond, Edward O Wilson and Tim Flannery.28 That some of these authors approach such views is to be expected (E O Wilson is the father of “sociobiology”) but other more recent converts to biological determinism have been surprising. George Monbiot, for example, in arguing for strong links between human prehistory and megafauna extinctions, laments: “Is this all we are? A diminutive monster that can leave no door closed, no hiding place intact… Or can we stop? Can we use our ingenuity, which for two million years has turned so inventively to destruction, to defy our evolutionary history?”29

These essentially sociobiological arguments are compounded by their advocates’ simplified interpretation of the relationship between humans and nature. In this regard these commentators are guilty of ecologism: “the use of ecological terminology or simplistic interpretations of ecological concepts in support of political or moral arguments”.30

Tackling biological determinist and ecologist arguments is important because of their assumptions regarding human behaviour and the implications of such for human-nature relations. Biological determinism (sociobiology and its contemporary expression as evolutionary psychology) assigns all human social and cultural behaviour to fixed genetic and evolutionary origins.31 If this holds, then humanity’s role as harbinger of the biodiversity crisis carries a degree of historical inevitability since it suggests that humans are inherently harmful for biodiversity and that human-nature relations will forever be conflict-ridden. The options open to us from this are limited: either enforce authoritarian control over the actions and the population size of our species (Malthusianism), or hope that somewhere deep within our genetic make-up we may hold properties that will counter our destructive tendencies (E O Wilson’s Biophilia hypothesis).32

As discussed already there are fundamental reasons why the argument that humans have been forever destructive of biodiversity does not hold. But the chief problem with biological determinism stems from its ontology. By placing human society and history within the straitjacket of biological determinism, these commentators are guilty of disciplinary cross-contamination. As biologist Richard Lewontin points out, “Biology is not physics, because organisms are such complex physical objects, and sociology is not biology, because human societies are made by self-conscious organisms”.33

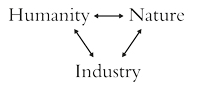

Marx and Engels argued that the historical and material basis for human society is derived from the dialectical interrelationships between human beings, our productive activities and nature.34 The Hungarian Marxist István Mészáros describes this as a “three-fold interaction” between humanity (or “Man”), human productive activity (Industry), and ecology (Nature). Mészáros illustrates this structural interrelationship with a clear schematic diagram:35

For Mészáros, the essential processes of historical dynamism within human society are revealed through the schema’s double-headed arrows since these indicate “dialectical reciprocity…between all three members of this relationship which means that ‘man’ is not only the creator of industry but also its product. Similarly, of course, he is both the product and creator of ‘truly anthropological nature’—above all in himself, but also outside him, insofar as he leaves his mark on nature”.36 This is a particularly important consideration since it reveals the central problem facing those conservationists who, through their ecologism, ascribe an anti-ecological character to our nature.

Humanity derives the basis for our nature from the biological characteristics that nature itself has facilitated through evolution (opposable thumbs, upright gait, large brain, consciousness). But these characteristics must express themselves upon each other, and the world, through the mediating operation of human society and industry (what Marx and Engels referred to as human “labour”). For Marx then, “human nature” (with its potentially inexhaustible range of societal expressions) is revealed through the three-fold dialectical reciprocity whereby human industry/labour determines the “natural essence of man”, and “the human essence of nature”.37

In contrast, sociobiologists, evolutionary psychologists, Malthusians, and those conservationists guilty of ecologism assume a ready-made, constant and uniform human nature that is derived solely through evolutionary or genetic means. Here an unmediated relationship between humanity and nature is presented:

For such scientists, human nature expresses itself through neo-Darwinian concepts such as competition, fitness and selfish genes. Many of these commentators would be quite happy to describe themselves as philosophical materialists. But, Mészáros argues, in reality, such thinkers idealise “the unmediated reciprocity between man and nature…they get themselves into the impasse of [an] animal relationship from which not a single feature of the dynamism of human history can be derived”.38

The problem with such an approach is immediately clarified when applying Marx’s materialist analysis of alienation. The mediation of humanity’s labour (industry or productive activity) provides us with an escape route from ecological fatalism, since it has the dialectical potential for humanity to at once dominate and live within the bounds of nature. Industry carries “an essentially positive connotation in the Marxian conception, rescuing [us] from the theological dilemma of ‘the fall of man’”.39

Conclusion: which Anthropocene?

Around the same time that WWF released their 2014 LPI report a group of geologists were gathering in Berlin to discuss the naming of a new geological epoch: The Anthropocene. Inspired by the obvious fact that human agency has now come to dominate the fate of life on Earth, for good or for ill, these scientists were also trying to determine the point at which this human takeover of the planet should be marked geologically. Some argue that the Anthropocene started with the systematic exploitation of fossil fuels during the industrial revolution, others that the use of nuclear weapons in the 1940s would be a more long lasting geological marker. The thought of geologists, with their deep-time consciousness, quibbling over a few hundred years of history is both confusing and entertaining. But the issue is serious because their confusion reveals the astonishing geological speed with which capitalism is changing the Earth’s ecology and biodiversity.40

At the heart of capitalism, and its “social metabolic order of reproduction”41 lies a particular ecology. This ecology is destructive of both pre-capitalist and non-capitalist biodiversity.

The ecology that is actively engineered under capitalism is one determined by ruling class aspirations for profit. The mechanisms whereby capitalist ecology is formed—to the exclusion of other ecologies—are embedded within familiar elements of bourgeois society: commodities, markets (national and international), privatisation and dispossession, state actions, imperialism and class chauvinism.

To date, capitalism has only been able to sustain its rejection of nature and its destructive ecological tendency through pulling in artificial ecological commodities from various arms of capitalist industry—for example in agriculture. This creates a dysfunctional ecological tendency towards ecological uniformity and simplicity inevitably resulting in biodiversity loss and extinction.

The long-term societal ramifications of capitalist ecology are frighteningly unclear (outside of the obvious violence that capitalists utilise to accumulate land and resources). It may be, as David Harvey comments,42 that the contradiction of ecological destruction could be a self-made storm that capitalism has the potential to weather. Or it could be that the monocultural vulnerability of our food chain will lead to painful collapse with serious implications for conflict under capitalism and a narrowing of the ecological horizons for a post-capitalist world.

Whatever the implications for human society, the extinction consequences for life are becoming very clear. Whether considered from a multi-generational perspective or that of the Earth’s geological timeline—the Sixth Extinction is a further symptom of the “regression of bourgeois society into barbarism” that Rosa Luxemburg warned us about a century ago.43

The implications for our broader human condition are also very serious. At best, the unfolding extinction crisis represents an erosion of our own nature through the narrowing of our perceptual horizons and increasing isolation and alienation from nature—ie an increasing loneliness of our collective species being. At worst, capitalism’s biodiversity crisis represents a destabilising drive towards vulnerable ecological uniformity. As biodiversity is diminished our societal options and life-support systems may be degraded to the point where environmental destruction contributes to “the common ruination of the contending classes”.44

The outcome of the class struggles to come will determine whether the biodiversity loss associated with our Sixth Extinction can be halted or reversed. The results of the struggle will also determine whether the Anthropocene becomes measured in deep time as a geological epoch under socialism (with a historically viable ecology), or a short, sharp catastrophic event under capitalism.

Notes

1: Go to www.catalogueoflife.org

2: The final tally for existing species probably depends on the number of beetle species that we can identify in the tropics and the ability of taxonomists to do so before they are lost.

3: A particularly virulent pathogen that has become one of the major causes of amphibian declines across the world. Its spread dates back to the 1930s when African clawed toads were exported around the globe to produce frog-based pregnancy tests within medical establishments.

4: The LPI programme is run by WWF (World Wide Fund for Nature, one of the largest international conservation NGOs) and the Zoological Society of London (ZSL)—WWF, 2014.

5: McCallum, 2015.

6: McCallum, 2015, p2.

7: Leakey and Lewin, 1997. Kolbert, 2015.

8: The IUCN produces a “red list” each year detailing the status of over 75,000 species—www.iucnredlist.org

9: Barnosky and others, 2011, p56.

10: Harvey, 1996, p174.

11: Conservation grazing is used to manage habitats that are actually relics of historical land use. For instance, in the case of Northern European species-rich meadows a low number of livestock should ideally be introduced to graze fields following the late summer hay cut. Historically, such “aftermath grazing” would have helped replenish the nutritional diversity of the hay crop through the opening up of the sward by livestock, and the replacement of lost nutrients through manure.

12: Richards, 2003, p17.

13: Jones, 2011.

14: Mann, 2011; Richards, 2003.

15: Flannery, 2011, p98.

16: Clay, 2003.

17: Marx, 1990, p125.

18: Choonara, 2009, p14.

20: Altieri, 2000, p78.

21: See Wood and others, 2000.

22: Wood and others, 2000, p12.

23: See Helm, 2015.

24: See WWF, 2014, and www.naturalcapitalinitiative.org.uk

25: Recent arguments put forward by Tony Juniper, one time head of Friends of the Earth, and others have been discussed previously in this journal—Churchill, 2014.

26: Diamond, 1992.

27: Kolbert, 2015.

28: See Brand, 2010; Lovelock, 2006; Diamond, 1992; Wilson, 1992; Flannery, 2011.

29: Monbiot, 2014.

30: Allaby, 2005, p146.

31: Rose and Rose, 2001.

32: The Biophilia hypothesis argues that there is an emotional, instinctive bond between humans and non-human life. This bond is offered as a product of human natural selection itself—Wilson, 1993.

33: Lewontin, 2001, p264.

34: Foster, 2000; Empson, 2014.

35: Mészáros, 2006, pp103-104.

36: Mészáros, 2006, p104.

37: Mészáros, 2006, p104.

38: Mészáros, 2006, p105.

39: Mészáros, 2006, p108.

40: Sample, 2014.

41: Mészáros, 2008.

42: Harvey, 2014.

43: Luxemburg, 1915.

44: Marx and Engels, 2000, p35.

References