Two years have passed since John Parrington wrote in this journal that “if governments across the world had taken prompt action to stop the spread of SARS-CoV-2 in its tracks, much of the current crisis could have been avoided. Instead, we are faced with an escalating death toll”.1 We are now better placed to make a judgement on how well or badly states have performed, asking the question: can capitalism ever manage pandemics that in any way puts people before profits?

It is worth stating at the outset that no capitalist state wants pandemic disease to run riot through its territory. There are social, political and economic reasons for this: social because high death rates undermine the consent on which all ruling classes at least partially depend; political because governments can become destabilised and fall; economic because of the disruption to production and ultimately to the creation of surplus value and profits. At the same time, our rulers can be indifferent to the health and wellbeing of large sections of the population and, just as with climate change, parts of the ruling class can be affected by anti-scientific views that align with their own purposes.

The international dimension of state responses is critical, as the Omicron variant of Covid-19 reveals particularly sharply.2 Here we face the problem of a capitalist world economy divided into rival nation-states, each responding to pandemics in the context of inter-state economic competition. Their policies are constrained by this context; they have to avoid falling behind competitors and must gain advantage over their rivals. This puts even the more successful efforts to eliminate Covid-19 under pressure. The phenomenon of “vaccine imperialism”, discussed below, is a product of this broader competitive and imperialist order.

States have by and large concentrated on a mix and match of three different strategies. The first is denial, arguing Covid-19 is no worse than a bad flu and that herd immunity will gradually be acquired. According to this approach, the whole population should be allowed to become infected and thus gain immunity in the hope of minimising major disruptions to economic and healthcare systems, and limiting deaths to the elderly and “unproductive”. This strategy was originally proposed in Boris Johnson in Britain, Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil and Donald Trump in the United States. Their gamble was that they could ride out the pandemic and gain economic advantage through not shutting down. However, this approach was rapidly discredited, and states that locked down earlier, before case rates got out of hand, tended to fare better.

The second strategy is “containment and mitigation”, aimed at preventing health services from being overwhelmed (“flattening the curve”). This approach was prepared to use robust methods of lockdown and other restrictions when transmission rates were high; then, as rates fell, restrictions were rapidly eased off. This often results in cycles of lockdowns followed by relaxation of restrictions. Vaccinations were then seen as the way out of this cycle. To a greater or lesser extent this strategy was adopted in most of Europe, including eventually in Britain.

The third strategy is known as “Zero Covid”. It has been implemented, with significant variations, in Australia, New Zealand, Taiwan, Vietnam, China, South Korea and a few other countries. It aims to keep transmission of coronavirus close to zero, eliminating the disease from a particular territory. This strategy does not aim at worldwide eradication of the virus; such a feat has been achieved by humans for very few diseases, smallpox being a notable exception. Elimination rather means a reduction to zero or a very low rate of new cases through ongoing and deliberate efforts, requiring measures to prevent re-establishment of disease transmission.3 The Delta variant, and even more so Omicron, have made Zero Covid harder to achieve due to their greatly increased transmissibility, as well as because variants such as Omicron have a partial ability to evade vaccines and naturally acquired immunity.4

According to its proponents in the public health movement, a Zero Covid strategy should have the following elements:

• Full lockdown till new cases in the community have been reduced to close to zero.

• An effective find, trace, isolate and support system to quash further outbreaks.

• Covid screening and, where necessary, quarantine at all ports of entry.

• A communication strategy that is consistent, seeking to generate trust and social solidarity rather than stressing individual safety and compliance.

• A guarantee of the livelihood of everyone losing money due to the pandemic.5

This article examines how the Zero Covid approach compared to other strategies and how it might be limited when implemented within a capitalist world order. It also asks questions about who drives the control mechanisms involved in such a strategy. There are differences in how a largely authoritarian state (albeit one with some social base) such as China imposes a lockdown and how a parliamentary democracy such as New Zealand does so. The article also considers the issue of vaccines and vaccine imperialism in the context of the global pandemic.

Global and historical comparisons

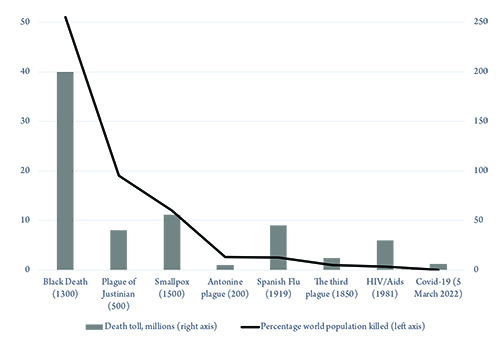

Covid-19 has been the worst viral pandemic in the past 100 years. However, it is also worth remembering that Covid-19 has so far been a relatively mild pandemic by longer historical standards, and future pandemics could be far worse (figure 1). The latest World Health Organisation (WHO) estimate of Covid-19 deaths worldwide is just under 15 million, though true numbers are undoubtedly higher.6 The 1918 “Spanish” flu pandemic killed four times that number, over 50 million, and infected 500 million people, one third of the world’s population at that time.7

Figure 1: Deaths due to pandemics (year of estimate in brackets)

Source: www.visualcapitalist.com/history-of-pandemics-deadliest

Back then, there was no vaccine to protect populations and no antibiotics to treat secondary infections. Control efforts were limited to isolation, quarantine, use of disinfectants and restriction of public gatherings, which were applied unevenly. Nonetheless, when we start examining how our today’s states have dealt with Covid-19, we need to be mindful that we have been lucky that SARS-CoV-2 has not been as virulent as the 1918 flu.8

Within this context, however, the experience in various countries has been markedly different. Table 1 shows a stark difference in death rates between Zero Covid countries at the bottom and herd immunity or containment and mitigation countries at the top. The contrast was starker still before Omicron. The success or otherwise of vaccination programmes has so far not been reflected in the total death toll, although this may change in the future. I will now look in more detail at how some countries have implemented specific versions of a Zero Covid strategy.

Table 1: Impact of Covid as of 13 May 2022, ranked by death rate

|

Country |

Cases per million people |

Deaths per million people |

Percentage fully vaccinated |

|

Peru |

105,578 |

6,297 |

81 |

|

Hungary |

198,647 |

4,820 |

64 |

|

Brazil |

142,266 |

3,086 |

77 |

|

US |

251,239 |

3,067 |

66 |

|

Russia |

124,959 |

2,584 |

50 |

|

Britain |

323,270 |

2,578 |

73 |

|

Portugal |

388,101 |

2,211 |

93 |

|

Sweden |

245,188 |

1,846 |

75 |

|

South Africa |

63,777 |

1,658 |

31 |

|

Germany |

304,526 |

1,633 |

77 |

|

Denmark |

510,303 |

1,076 |

83 |

|

South Korea |

345,213 |

460 |

87 |

|

Australia |

249,578 |

296 |

84 |

|

New Zealand |

206,060 |

178 |

80 |

|

China |

154 |

4 |

87 |

Source: compiled from www.worldometers.info and https://ourworldindata.org

China

China was the first country to be hit by Covid-19. After an initial phase of bungling, involving silencing of whistle blowers, the response of the Chinese elite took advantage of a highly centralised state with a centralised epidemic response system. There was also a fresh memory of the 2002-04 SARS epidemic, which had a significant number of deaths associated with it. Nonetheless, China was vulnerable because most of its frail elderly live with or close to their families.9

The Chinese state’s response came in four phases. The first phase was from December 2019 to January 2020, when cases were rising rapidly but the government did not recognise Covid-19 as a public health threat; there was suppression of the news and no transparency regarding cases. It is worth noting that China had massively disinvested in public health since the “barefoot doctor” days when collective state institutions were directly responsible for all healthcare. It went into the pandemic with a very low annual public health expenditure of US $323 per capita, half that of Brazil or Bulgaria.10 There have recently been frequent public health scandals, notoriously involving poorly regulated firms cutting baby milk with the chemical melamine in 2008 and fake HPV vaccines being used in hospitals. The disconnect between local bodies, health workers and the central authorities they were trying to alert resulted in suppression of news about the outbreak, causing it to nearly run out of control.

This was, however, followed by dramatic action in the second phase. In the scientific domain, China released the genomic sequence of the virus on 10 January 2020, allowing an early international start on vaccine development. It enforced a rigorous lockdown in the city of Wuhan, lasting 76 days, with public transport suspended. Similar measures were adopted in every city in the wider Hubei province. Some 14,000 checkpoints were established across public transport hubs to prevent travel. The 40-day Chinese spring festival, when migrant workers usually travel across China to visit their families, involving about three billion trips, was cancelled. Only one family member was permitted to leave the house every couple of days to collect food supplies. Within weeks, China had tested nine million people for Covid-19 in Wuhan alone. Linked to the testing was an effective national contact tracing system. Production of personal protective equipment (PPE) was quickly ramped up, and the Chinese population adopted mask wearing with high compliance. Drones with loudspeakers rebuked citizens disobeying the rules. A network of emergency fancang (“square cabin”) hospitals were set up to isolate patients with mild to moderate symptoms so that these patients did not have to isolate at home, spreading Covid-19 to their families. These early measures were critical in preventing Covid-19 from establishing itself across China and have been modelled to have prevented 56,000 deaths in this early phase. Throughout 2020, outbreaks occurred in other parts of China and were dealt with through similar measures. These measures got case numbers down to low figures, though not to zero. They could not have been effective without a large mobilisation of the population in support of the measures.11

A third phase involved stamping out hidden coronavirus risks in particular areas. Starting in May 2020, coronavirus testing was carried out house to house, with ten million tested over ten days. This process discovered, for example, 300 asymptomatic cases in Wuhan. Similarly, in Beijing, 12 million were tested and 174 were found to be positive and told to isolate. This allowed a controlled reopening of workplaces and production from this time.

Finally, in phase four, the country moved into a permanent state of surveillance, being split into low, medium and high risk areas, which could be as small as a single housing estate. All citizens have an app on their phones indicating the current status and location, and their movements are regulated accordingly. A near normal life is only permissible if your app shows green. The vaccination programme played a small part in all of this, not getting underway until March 2021. The result was that the epidemic in China was brought under control with no significant second wave until the recent Omicron outbreaks.

Omicron, with its increased transmissibility, has stretched this strategy to its limits, notably with the outbreak this year in Shanghai. Lockdowns have needed to be harsher than before in order to contain Omicron. Yet, for China to retreat from its Zero Covid strategy will be difficult. Antibody levels in the population are low due to the absence of infection and because of the lesser effectiveness of the country’s Sinovac vaccine.12 There is more data on this from Hong Kong, where the March 2022 Omicron outbreak resulted in an enormous 1.2 million cases and over 9,000 deaths in a population of 7.6 million. Virologist Siddharth Sridhar at Hong Kong University’s Department of Microbiology said the city’s death rate—among the worst in the world—was “tragic but expected”, pinning it on a “perfect storm” of low vaccination rates among elderly people, low rates of prior infection and an overwhelmed healthcare system.13 Outside of the major cities, China’s healthcare system is insufficiently resourced to cope with a huge elderly population at higher risk of severe illness.14 Moreover, the costs to the economy may mount up if lockdowns become the norm when trying to contain Omicron.

The issue of consent is important in the Chinese context too. The Chinese state cultivates the ideological self-image of a strongly collectivist society, but it is also a very highly surveilled one, especially in the cities, where over half of people live. Most of the urban population reside in compound-style housing, normally moving about freely. However, there are cameras discreetly placed on entrances to housing complexes, and it is easy for shequs (neighbourhood committees) to set controls on movement. These committees are effective in ensuring that locked down populations get food and other necessities, but they could not manage this without considerable participation from the public. This has included unofficial organisation established to transport essential workers when trains and buses were halted, to source PPE before the state had increased supply, and to deliver food to apartment blocks when supermarkets were closed. A strong memory of the earlier SARS outbreak led to a greater preparedness on the part of government, leading to attempts to swiftly organise supplies of vaccine and testing.15

Although the system put in place to control Covid-19 relies on repression, it is also true that this is seen by many as necessary. Indeed, some Chinese scholars regard “the low human rights advantage” of China as crucial to its success.16 At the start of the outbreak, the Zero Covid policy was at least broadly tolerated in the absence of an alternative based on genuine socialism and collective solidarity from below. However, as outbreaks flare up, the question is being raised as to how long the policy can be sustained before public support tapers off. Social media criticism is mounting in affected areas, such as in the northwestern city of Xi’an.17 The outbreak in Shanghai places the policy under even more severe pressure; there, after more localised containment measures failed, the entire city of 26 million people was locked down.

This approach does not simply risk a loss of support from among the wider population; another pressure on China’s ruling class is the impact that the new outbreaks are having on the economy. At the start of the pandemic, the relatively brief, early lockdown put China at a competitive advantage, and production could continue unimpeded due to low levels of Covid-19. This is no longer the case. Foreign investors, including Apple, are raising the alarm and considering moving production out of China.18 China’s rulers are caught in a bind. Zero Covid is becoming increasingly costly but there is no easy way out.

South Korea

South Korea started out with three advantages in tackling Covid-19. First, policy makers had learnt from their previous mishandling of a Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) outbreak.19 Second, the country has an almost impermeable barrier to the north with North Korea and is surrounded by sea elsewhere. Third, it has a relatively high number of hospital beds—12.3 beds per 1,000 patients, compared to 2.9 in Britain (though admittedly many of these beds are in nursing homes).20 The government started its response quickly, developing diagnostic kits as early as 27 January 2020 and starting testing in mid-February. By contrast, Britain did not begin testing until April and was not at adequate capacity until August. So, contact tracing and isolation of those infected began early in South Korea. Quarantine was policed rigorously; contact tracers had access to the credit card transactions and mobile phone data of those asked to isolate, with fines issued to those in breach. Data was destroyed after two weeks, and generally South Koreans have been tolerant of this personal data sharing. The success of these policies has depended on the state’s ability to scale up technological solutions. However, despite being based on legislation from 2015 that allowed government access to personal information following MERS, state action has probably been pushed beyond what is legally permissible.21

By starting early with this data-driven approach, major lockdowns were avoided. Covid-19 cases were kept at around two new cases per day until an outbreak occurred in Daegu, a city of 2.5 million, with a spike around a particular church congregation that peaked at 909 cases. Daily cases then declined to near zero. There was another spike in mid-August around another religious group in Seoul, but this was controlled through limitations on indoor gatherings and stringent contact tracing. By September, cases had fallen to below 100 a day. Screening played a big part in controlling the spread of Covid-19, with around 600 screening centres being set up. Travel restrictions were imposed early in late January 2020; all travellers were tested at the border, and compulsory quarantine of 14 days was introduced.

More recently, with the advent of the Omicron variant, case numbers have risen, approaching 8,000 new cases a day towards the end of 2021 (figure 2). Failure of the young to vaccinate and the elderly to get boosters is being blamed. Faced with this, South Korea too has started to abandon its Zero Covid strategy. As early as November 2021, the government tried to push through its “living with Covid-19” strategy, which quickly and dramatically increased the number of patients. Only when the government was faced with a backlash did it partially reintroduce some preventive measures, but the find-trace-isolate system was now no longer as effective as it had been in 2020. The authorities have greatly relaxed their monitoring system against the close contacts of Covid-19 patients. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests have been replaced with rapid antigen testing, which is notorious for its low sensitivity. Only high risk groups can apply for a free PCR test without approval. The government has also removed support for isolation and treatment for patients, instead stating it will deal with Covid-19 in a similar manner to flu.

Figure 2: South Korea, daily confirmed cases (7-day rolling average)

Source: ourworldindata.org

New Zealand

New Zealand had a brief window to refine its strategy after Covid-19 emerged in China. Up until February 2020, the country’s epidemic contingency planning was based on its influenza strategy, a mitigation strategy focused on flattening the curve.22 New Zealand’s first case came on 28 February 2020, and by mid-March there were 800 cases, almost entirely among those recently returning from overseas and their contacts. The government decided to switch to an elimination strategy. A four-tier approach was introduced on 21 March 2020, with the country starting on level two, meaning limitations on mass gatherings and increased physical distancing. This was rapidly escalated to level four, with a lockdown involving closing all schools and non-essential workplaces as well as imposition of severe travel restrictions. Strict border controls were introduced—easier in a country composed of islands. There was effective case isolation and quarantine, and the communication strategy was consistent and well-coordinated, resulting in widespread popular support.

The strategy was successful in the early phases of the pandemic. By early August 2021, New Zealand had experienced five months without a single locally acquired case.23 However, on 17 August 2021, an outbreak started in Auckland, resulting in an immediate lockdown of the city. In October, case numbers rose to 1,350. The virus had taken hold in marginalised communities, which were more difficult to lock down. At a press conference on 4 October 2021, prime minister Jacinda Arden stated: “In this outbreak, it’s clear that long periods of heavy restrictions have not got us to zero cases.” She outlined a three-stage strategy to transition Auckland out of lockdown, despite the virus continuing to circulate. The advent of vaccines allowed her to argue for a mitigation strategy, abandoning the goal of elimination: “But that is okay. Elimination was important because we didn’t have vaccines. Now we do, so we can begin to change the way we do things”.24 Public health experts in New Zealand argued that the Delta variant had forced them to move beyond or partially abandon elimination. Dr Michael Baker, an epidemiologist at the University of Otago and one of the authors of New Zealand’s elimination strategy, told the British Medical Journal:

The government’s Covid-19 strategy was mapped out in August in its “Reconnecting New Zealanders to the World” plan… It included continuing with elimination until we had high vaccine coverage and then cautiously opening up to greater inbound travel while keeping case numbers low. This stage was expected to be reached in early 2022… This timetable was overtaken by events, with a prolonged Delta variant outbreak beginning in Auckland on 17 August. This outbreak was largely eliminated within 2-3 weeks of the lockdown. However, we had the bad luck that the virus became established in marginalised populations in southern Auckland, including motorcycle gangs and people living in emergency housing. This situation meant the outbreak continued at a low level for a further four weeks, and it now appears to be slowly growing. This, and the associated lockdown, started to erode the government’s social licence for continuing its vigorous response and also created real hardship for some households. That situation appeared to be a major factor in the decision to switch to less intense control measures.25

In the same interview, Professor Rod Jackson from the University of Auckland added:

Delta has forced us to move beyond elimination sooner than we wanted to. When Delta arrived here, we were only partially immunised. We almost got it under control, moving from 80 new daily cases or so down to the low tens of cases. But elimination was never an endgame: it was only a strategy until you had a good vaccination. Fortunately, now we do.26

However, most of New Zealand was still attempting to enact an elimination strategy while vaccinating. It is also worth noting that, if New Zealand had the same mortality as Britain, they would have experienced over 10,000 deaths instead of 47 (as of 14 December 2021).

At the time of writing New Zealand was bracing itself for Omicron, which had still not taken hold outside of isolation facilities. Because booster numbers are low, it was expected to be only a matter of time before this changed. While the government has enjoyed strong support for its policies, which have resulted in exceptionally low mortality rates, criticism from stranded New Zealanders unable to easily return home has mounted—it has been a lottery to try to get into one of the country’s oversubscribed managed isolation and quarantine centres.27 This is not the only issue with closing borders for a prolonged period. For instance, the New Zealand government has abandoned its commitments to refugees, bringing in fewer than 500, compared to an anticipated 1,500, in 2021-22.28 Moreover, in a highly integrated global economy, it is impractical for a ruling class to have an indefinite closed-border policy.

Australia

The first case identified in Australia, a man returning from Wuhan, was found on 25 January 2020. By 23 March, the country had just five new cases of Covid-19.29 Nonetheless, on 20 March, its international borders were closed and mandatory home isolation for returning citizens was implemented, with police conducting home visits to ensure returning citizens were adhering to regulations. When people were found to be breaching the rules, mandatory hotel quarantine was introduced; rooms were guarded by police officers and the military. So as not to overwhelm quarantine facilities, there was a cap on returnees, and 40,000 Australians were stranded overseas at one stage. Individual states within Australia then closed their borders. Non-essential businesses were closed. People were confined to a small area close to their homes and could not leave except for essential work and medical appointments. Households could not mix. The government introduced an AUS $130 billion bailout programme, which included a six-month wage subsidy scheme.

The rapid spread of the virus was thus halted, and case numbers began to dip by the beginning of April 2020, falling below 20 new cases a day. At various points, the country reached zero cases per day. This gave time for an effective testing and tracing infrastructure to be built. Local lockdowns remained in place, but states such as New South Wales and Western Australia were able to reopen after two months. There were further waves, for example, in Melbourne in May and June 2020, and these were dealt with by further lockdowns. When the Delta variant hit in June 2021, a new lockdown affected almost half of the Australian population. The Delta wave would upend Australia’s Zero Covid strategy, especially in Sydney and Melbourne, where greater reliance was now placed on vaccination, which had hitherto remained at low rates.

The government originally formulated its exit strategy as a three-phase process. Phase one involved rolling out vaccinations while keeping borders closed and imposing early and stringent but short lockdowns when outbreaks happened. Phase two was to kick in once 70 percent of the adult population were fully vaccinated, with only lower-level restrictions necessary. Phase three, when over 80 percent were vaccinated, would involve fewer restrictions still. Only when this was working would Australia open its borders to those countries deemed safe.30

Public support for Zero Covid remained strong even as late as August 2021 when, according to one poll, 58 percent of Australians supported lockdowns until higher levels of immunisations had been achieved.31 Trust in the integrity of the government was crucial in maintaining this level of public support. That has been gradually eroded—from 66 percent in August 2020 to 52 percent by August 2021—but still remains considerably higher than, for example, trust in the Johnson government in Britain.

However, as in New Zealand, even before Omicron the Australian government had begun to argue they could not sustain a Zero Covid strategy indefinitely. Prime minister Scott Morrison argued, “This is not a sustainable way to live in this country”.32 With Omicron, a crucial point was passed in January 2022, when cases surged beyond one million and the government abandoned its Zero Covid strategy. According to Morrison, “Omicron is a gear change and we have to push through. You’ve got two choices here. You can push through or you can lock down. We are for pushing through”.33

In one sense, he was right. Zero Covid strategies were not designed to be sustainable indefinitely. If they are to succeed, they must be adopted in all countries and would become less burdensome to maintain as more countries eliminated the virus. If this does not happen, they are only sustainable with a massive permanent transfer of resources to the strategy, which is ruled out by the economic rivalry between different capitalists and the states that represent their interests. Perhaps more credible is the idea that Zero Covid strategies can buy time for vaccines to come to the rescue. However, once again there is a problem here. This approach is only effective if vaccination takes place on a global scale. Otherwise, the continued widespread circulation of the virus will tend to lead to the proliferation of new strains of Covid-19. I will now consider how governments have managed the task of vaccinating the world.

Vaccine imperialism

Immediately prior to the emergence of the Omicron variant, wealthy countries were sitting on huge surpluses of unused vaccine.34 In late July 2021, the US had 26 million unused doses, with many due to expire in August. In Britain, even taking into account the assumption that 80 percent of those over 16 were to be vaccinated and boosters were to be given to higher risk groups, there were still 219 million surplus doses. The surplus could reach 421 million doses in 2022. Although expanding booster programmes will consume some of these, this in turn exposes another stark inequality—wealthier countries have consumed more Covid-19 booster doses than the total number given to those in poorer nations, despite the Global South comprising the majority of world population.35 Short expiry dates also limit the ability to donate unused doses to the United Nations’ Covid-19 Vaccines Global Access (COVAX) initiative. This is the case even when these expiry dates are unnecessarily short, since poor countries, rightly, do not want to be seen to be using vaccines that rich countries would refuse due to being past their expiration dates.

The lack of access to vaccines has persisted even though 12.2 billion doses of vaccine had been produced worldwide by the end of December 2021—more than enough for everyone on the planet to have had at least one dose. Even based on current vaccine production capacity, it would be possible within five months to vaccinate 75 percent of the world’s population. Yet, with the current uneven methods of distribution, it would take over five years to vaccinate just Uganda’s population to the 75 percent level. The degree of vaccine inequality is stark. At the end of October 2021, the World Trade Organisation (WTO) estimated that 65 percent of people in the world’s high-income countries were double vaccinated, compared to just 2 percent in low-income countries.36 So dire is the vaccine distribution situation that COVAX has moved its goal date for delivering two billion doses from the end of 2021 to the end of 2022.

This crisis cannot be solved by simply diverting vaccines from rich countries to poorer ones. Instead, Médecins Sans Frontières and other agencies see the major barriers as intellectual property restrictions, which the WTO strongly resists lifting. Vaccines developed with public money in public laboratories should be considered a public good, but instead are treated by the WTO as private property. The WTO’s 1994 Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights bans the copying of pharmaceutical technologies, allowing medical companies such as Pfizer to block approaches from potential producers in other countries. BioNTech, which developed the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine, is worried that waiving intellectual property rights would open it up to competition from Russia and China, which currently lack the technologies required to create mRNA vaccines.37 One economist estimates that BioNTech’s near monopoly on this technology could have contributed 0.5 percent to German GDP in 2021.38

Yet, vaccines can only be distributed effectively through an increase in production and diversification of where in the world they are manufactured. Pre-pandemic world vaccine production was almost exclusively situated in the European Union, the US and India (although China has become the largest exporter of Covid-19 vaccine, particularly after India’s Serum Institute halted exports because of the country’s vaccine shortage). The present system is based on COVAX being supplied as a form of charity by high-income countries. This model has not worked.

Instead, alongside the waiving of patents, what is needed is technology transfer. This has been proposed, for instance, by South Africa’s WHO-backed “tech transfer hub”, which has sought to replicate Moderna’s mRNA vaccine without support or involvement from the corporation. Without the relevant technical knowhow being transferred, removing intellectual property rights is insufficient. Moreover, the equipment required to produce these vaccines is in short supply. Each vaccine itself has up to 200 components. Prior to Covid-19, the world supply of the nanoparticles required to make mRNA vaccines consisted of just a few grams; now they are needed in quantities of hundreds of kilograms. None of the manufacturers of nanoparticles are located outside of Europe or the US. Yet, if the required technological transfer took place, mRNA vaccine production in poorer countries could become much easier than production of conventional vaccines. This is because mRNA vaccines use the patient’s body as the factory to make the antigens that stimulate antibody production. The problem of waiting months to grow cell lines, as is the case with conventional vaccines, is overcome.

However, any attempt to set up manufacturing outside of high-income countries has been restricted by “local supply first” policies—an area in which Joe Biden has maintained Donald Trump’s “America First” programme. Showcase examples of tech transfer have been only token. In July 2021, Pfizer announced a collaboration with South African company Biovac to produce 100 million doses annually for the 55 states in the African Union. Yet, Africa has a population of over 1 billion. Meanwhile, Bangladeshi company Incepta has sought licences to manufacture mRNA vaccines from Pfizer, but Pfizer has so far refused these approaches.39

The twin problems of the protection of intellectual property and technology transfer are condemning millions to death. Added to this, Omicron has dealt a big blow to the idea that is possible to vaccinate our way out of the pandemic without enacting a mass of other public health measures. Vaccination may have reduced the severity of outbreaks in well-immunised countries, but it did not prevent a huge winter wave of infection in 2021-2022, which again threatened to overwhelm healthcare resources in advanced western countries.

Conclusion

It has become a commonplace to say that “no one is safe till everyone’s safe”. The Delta and now the Omicron variant have reinforced that point. The pool of Covid-19 virus in the world remains and will be a source of new variants, possibly more virulent than those seen so far. The Covid-19 pandemic is illustrating in a chilling way that the two main sets of methods for bringing the pandemic to a close are impossible to deliver in a world that is run as a system based on capitalist competition. First, the conventional public health measures, encapsulated by the phrase “Zero Covid”, are breaking down, because few countries’ ruling classes were prepared to adopt them. Second, there seems no way out through vaccines, which can only work in the long term if the whole world is immunised.

Given this, we face the prospect that Covid-19 will become an endemic disease worldwide, meaning it is here to stay. There is no certainty that this will mean it will become a mild infection such as the common cold and seasonal flu. Like malaria in the Global South, it may well exert a grim toll for a long time to come. Furthermore, as capitalism’s incursions into ecosystems and its characteristically pathogen-creating food production methods are unlikely to change, new pandemics are to be expected in the future.

As hopes for the success of Zero Covid strategies recede, what can the left do? We certainly need to expose the failures of those who govern us, who have not done enough to curtail the spread of the virus. The handful of countries that sought to go down a different path testify to what could have been achieved with early, properly applied conventional public health measures. However, even these examples show the limitations of such an approach in a world driven by inter-state competition. We need also to expose the failure to vaccinate the world; had this happened promptly, it would have considerably reduced the pool of infected people in which new variants have the potential to develop. We need also to oppose the attacks on civil liberties through vaccine passports, increased border controls and any other increases in government powers rushed through during the pandemic. Indeed, controls on crossing borders might have been justified as temporary impositions when it was possible to nip the pandemic in the bud, but they can no longer be justified on public health grounds in an endemic situation.

Covid-19, along with any new pandemics that follow, remains one of the major crises facing the world, alongside climate change, inter-imperialist conflict and the threat posed by nuclear war. The relentless greed of our competing ruling classes—the band of “hostile brothers” that Karl Marx wrote about—is stopping them from bringing the pandemic to a close.40 Today, the choice remains socialism or barbarism.

Kambiz Boomla is an honorary senior lecturer at Queen Mary University of London and a retired GP. His took his master’s degree in Public Health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. He is a long-standing member of the Socialist Workers Party.

Notes

1 Parrington, 2020.

2 Omicron, detected in November 2021, is more transmissible than previously dominant variants.

3 Dowdle, 1999.

4 The Delta variant was first detected in late 2020, becoming dominant by the end of 2021.

6 World Health Organisation, 2022.

8 Virulence refers to the severity or harmfulness of a disease or virus, that is, how unwell it makes those who get it. This is distinct from a virus’s level of transmissibility.

9 Burki, 2020.

10 Chuang Collective, 2020.

11 Chuang Collective, 2020.

12 He, 2022.

13 Hutton, 2022.

14 White and Olcott, 2022.

15 From personal communication with Professor Steve Smith.

16 Hui, 2020.

17 Gan and George, 2022.

18 Olcott, Lin and Hollinger, 2022.

19 This MERS outbreak occurred in 2015.

20 Kim, An and others, 2021.

21 Scott and Park, 2021.

22 Baker, Kvalsvig and others, 2020.

23 Klein, 2021.

24 Dyer, 2021.

25 Dyer, 2021.

26 Dyer, 2021.

27 Power, 2021.

28 Whyte, 2022.

29 Haseltine, 2021.

31 Murphy, 2021.

32 Economist, 2021.

33 Jose, 2022.

34 Feinmann, 2021a.

35 Mancini and Stabe, 2021.

37 Only relatively recently developed, mRNA vaccines use messenger RNA rather than pieces of actual viruses to trigger an immune response. This technology has proved successful in rapidly developing Covid-19 immunisation.

39 Feinmann, 2021b.

40 Marx, 1972, p253.

References