From the early summer to the early winter of 2017 several industrial action campaigns were making the news, both nationally and at more regional and local levels.

Rail workers employed by Mersey Rail, Northern Rail and Southern Rail were mounting days of action to “keep the guard on the train”. British Airways cabin crews were striking repeatedly through these months over pay. In the manufacturing sector, BMW workers had struck in defence of pensions; and earlier in the year Fujitsu workers had walked out in protest against mass redundancies. The education sector had seen days of action by UCU members at Manchester Metropolitan University against redundancies and the closure of a major site, at the University of Brighton in defence of trade union rights, at the University of Leeds in defence of academic freedom and by further education college lecturers in Scotland over pay. School teachers in the South East had been on strike against education cuts. In the retail sector, Argos warehouse workers had been on strike over working conditions and against outsourcing. Yorkshire social workers had also struck against outsourcing and Jobcentre workers had walked out against closures in Sheffield. Cleaners at the London School of Economics had taken successful industrial action, again against outsourcing, as had cleaners at the School of Oriental and African Studies. The beginning of the year saw strikes on the London Underground against the closure of ticket offices, by cinema workers over pay and by Woolwich ferry workers over safety. By the end of the summer, housing contract workers in Manchester had been on strike for four weeks, outsourced health workers in east London had launched a series of five-day strikes and refuse workers in Birmingham had won over safety conditions and work rosters following a series of walkouts. This brief sample will no doubt have missed numerous other local disputes.

Strikes are an ever present reality in Britain. Indeed, some of the industrial action campaigns mentioned above, especially those of the British Airways cabin crews and rail workers, were quite impressive for the national profiles they were achieving and for the numbers of days of action planned. In all these cases the strikes were important in raising the profile of the unions involved. They were obviously important for the striking workers themselves and for the socialist activists who became involved in delivering support and solidarity. However, when seen against the backdrop of the UK national statistics for strike action in this period, they stood out in an industrial landscape that was otherwise quite uninspiring for revolutionaries.

The most recent Office for National Statistics (ONS) strike figures for the UK make this all too clear. As the ONS report for the year 2016 showed, the number of strike days was the eighth lowest since records began in 1861.1 The figures for the previous year had in fact been the lowest. The 2016 figures were raised above this historically low level by a single dispute—that of the junior doctors in the NHS—which accounted for 40 percent of all working days lost. Perhaps more surprising still, 2016 saw the smallest number of ballots for strike action since these records began in 2002:2

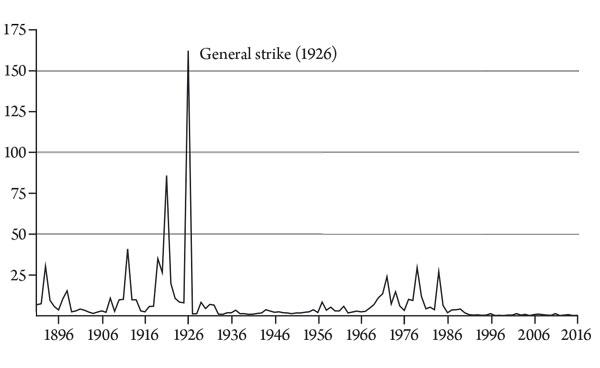

In 2016, working days lost to strikes was just 322,000, a tiny fraction of the 29 million in 1979 and the all-time high of 162 million in 1926, the year of the General Strike. Even during the Second World War, when emergency legislation in effect banned strikes, the number of days lost to industrial disputes stood at about 2 million a year.3

A glance at the recent levels of strike activity in the UK on a historical timeline illustrates the current extraordinarily low rate of industrial action (figure 1). Strike and ballot figures of course vary continuously, and are influenced by a range of structural and contingent factors from one year to the next. However, it is the contrast between the provocations launched upon the working population in recent years, and particularly the poorest workers and their families, and the relative quietude of the trade union movement that presents the left with such a problem of practical orientation and such a conundrum to explain.

We might have thought that, since 2010, public sector pay freezes, government orchestrated slides in the real-terms values of the minimum wage and of benefits, swingeing cuts to government services and jobs, and the most savage ever assault on the welfare state and the poorest in society would have produced a higher level of resistance by the traditional organs of working class defence—the official trade unions—than this.

Figure 1: Working days lost (millions), UK, 1891 to 2016

Source: Office for National Statistics, 2017

Explaining the situation: the International Socialism debate

The flatlining of trade union combativity at this low level, and for so long, has been the subject of debate within and beyond the pages of this journal. For some, changes to the industrial composition of the British working class make up the greater part of any full account of the decline in worker actions over the last two decades. For instance, the rise of precarious types of employment in which workers do not have standard contracts, have no control over their hours and little in the way of basic entitlements or protections has been used by authors such as Guy Standing to coin the new sociological category of the “precariat” to explain what is going on.4 In this journal Neil Davidson provoked healthy controversy with an analysis of the changes being wrought by “neoliberalism” with the decline of sectors traditionally characterised by high trade union membership densities, and the rise of new and largely unorganised sectors.5 The issues thrown up by such structurally-focused explanations anticipated some aspects of the more recent discussion about the low frequency of strikes in the UK.6 The purpose here, however, is to comment on this more recent “strike debate”.

My own first contribution to the debate looked at the restriction of official national strike action to very short periods (often just a single day), and its effect on cultures of local leadership.7 In this analysis, the “one-day strike” as a type of official action starves local activists of the experience of making independent tactical judgments, assessments of the balance of risks in taking action and so on. Over time, the result is dependency on national official leaderships in setting the agenda for action, controlling forms of input from the membership and determining the types of action that transpire, as well as their eventual conclusion.

Simon Joyce’s contributions have laid out the increasingly hostile climate for trade unions that has emerged over the last two decades. Joyce has emphasised, particularly, the decline of economic sectors once characterised by high union memberships, the introduction of legislation that has hemmed in the room for manoeuvre for trade unions and the experience of defeat over this period.8 Against this backdrop, he has foregrounded a specific cause of the decline of strike rates in the UK: “The fact that the strike weapon has been taken out of the hands of shop stewards” and handed over to national officials.9 This “strike weapon” thesis, is counterposed to the “confidence thesis” that he says has been used to address the problem by others in the debate.

Richard Morgan’s contribution, which draws on his own personal experience as a strategically-based union activist in the manufacturing sector, emphasises that employers will often try to avoid industrial confrontations, as well as the related phenomenon of “ballot victories” in which employers settle disputes following a successful ballot for action, rather than risk an actual strike.10 Other contributions have taken up different aspects of the debate as it has evolved, including: the nature of the “bureaucratic mass strike”;11 interactions between official and unofficial strike action;12 and the role of political consciousness in shaping the “balance of forces” between the working class and the capitalist class.13

The debate has been one of this journal’s most sustained and searching, touching as it does on a fundamental matter for Marxists: the ability of the working class to act as a class, and with the potential to change society. The debate continues and there is much that is still to say. For now, I wish to make just two comments about the debate thus far, before moving on to fresh analysis, and concluding with some reflections upon practical orientations: firstly, that our understanding of historical causation requires better definition in order to take the debate forward; secondly, that our analysis of the role of the Labour Party in opposition and in government needs to be further developed to provide a fuller account of the low UK strike figures.

What do we mean by “cause”?

Types of historical causation vary in their specific relationship to the effect that they produce. To put it another way, a cause that gives rise to a specific episode or historical trend can be referred to as a “proximal” cause. A proximal cause always appears in close connection to that effect but it does not have a deeper significance in explaining larger historical processes that are made manifest in myriad ways. For that, we need to identify “substantive” causes as distinct from proximal factors, working at a deeper level to produce many effects, which in their totality constitute any given historical juncture. As we have seen, some contributions to this debate have indeed looked to long-term trends in the UK economy. Martin Upchurch insists for instance, that we make changes in the dynamics of capital accumulation within British capitalism central to our understanding of the situation.14 The secular decline of economic sectors that were historically characterised by high levels of union density and militancy is also a part of the analysis offered by Joyce.15

It would be difficult to sustain an argument that such trends have had no effect on trade unionism in the UK. Until new sectors of the British economy see higher rates of trade union density and industrial struggle, the decline of sectors that have been key for the trade union movement will continue to play a role in depressing the annual strike statistics, alongside other factors such as hostile legislation and the experience of defeats. The debate here is rather about the relative weight of such trends as explanatory factors, and relatedly, whether they should lead us to pessimistic assessments of the prospects of raised levels of industrial struggle anytime soon. Some contributors have pointed out, for instance, that various types of structural analysis cannot be regarded as sufficient in explaining what is going on today, when we consider the historic expansion of new non-manufacturing sectors such as health and education, as well as the proletarianisation that characterises them.16

Contributions to the strike debate have also centred on proximal causes that can explain a specific effect—the curtailing of strike action in particular circumstances. We will consider the example of this tendency mentioned earlier that has attracted extensive comment: Joyce’s argument about the removal of the strike weapon from the hands of local stewards. The virtue of this idea is that it suggests a mechanism by which the desire of workers to strike, expressed repeatedly in ballots that return positively for industrial action, is blocked. Local activists, frustrated by the failure or refusal of national officials to translate “Yes” votes in ballots into action that is more than tokenistic, find themselves unable to deliver anything independently of the national officials.

The problem here is not that the “strike-weapon” thesis doesn’t capture an important truth: it does. In fact, it is worth considering this in more detail. There are many aspects to it: having to obtain authorisation for action even following a successful ballot; the use of indicative ballots ahead of actual ballots; the difficulty of winning official support for action that is disruptive rather than merely demonstrative, and so on. All of these things and more have become normal to the frustrating experience of being a local trade union activist in Britain today. There are no surprises in Joyce’s analysis here. However, in emphasising this single factor so exclusively, he stumbles into the same “chicken or egg” problem of which he accuses others in the debate.

The removal of the strike weapon is just such a “proximal” cause, as described earlier. In other words, it is specifically associated with the particular effect that is under scrutiny: in this case, the failure to deliver strike action in any given situation. There will, of course, have been many situations in which this will have been the reason that a strike did not go ahead when workers clearly wanted it to happen. However, this can be true also when workers are not confident to go ahead with action in the face of opposition from a regional official, so voting with them for some compromise. In other situations, the fact that the local reps are bogged down in a redundancy-avoidance consultation during a large-scale restructuring exercise will be the reason that action is stymied. In still others, it will have been the co-option of a key branch officer into the regional office’s sphere of influence; and at a crucial turning point in a dispute. Each particular episode will differ with regards to the proximal cause of action not happening when there is the potential for it to go ahead. The problem begins, however, when the emphasis is on a single factor to provide a general explanation of the phenomenon—the low strike rate in Britain. This is a problem because looked at one way the chosen factor may be a cause, while looked at in another way it may also be an effect, itself in need of explanation. This applies to Joyce’s thesis. Focusing on the “removal of the strike weapon from local stewards” begs a question—“but how did that happen?”—in just the way that an explanation based on, for example, “worker confidence” does.

Seeking a substantive cause: “history in the present”

In deepening our understanding of the industrial situation in the UK, there is a snowball of interacting factors to consider. Several have been identified and pondered in our debate. My own view is that no contribution so far has been sufficiently historical to explain the shifting strike pattern properly. Where comrades have offered historical analyses, these have been used to address specific aspects of the debate, rather than as the foundation for a full explanation of what is going on.17 A correct historical approach, I believe, enables us to move beyond the types of analysis that I will simplify as that of picturing a trade union movement that is shrunken in size and density compared to its 1970s heyday, is cowed by the experience of defeat and is operating in a far more difficult environment caused by relatively high unemployment levels and anti-strike legislation, but which in its essential nature is unchanged. My argument is that although these factors are real and relevant, the trade union movement itself has fundamentally changed in nature (in other words, not simply in industrial composition) over the last four decades, and in ways that we are only now beginning to face up to. To understand this internal alteration, we need to consider the historical changes to the socio-legal framework within which British trade unions operate, and with which they co-evolve in symbiosis, as well as the critical role of the Labour Party in the process.

Before explaining further, I will resolve our question into two, which I believe are directly relevant to the issue. My attempts to answer each will inter-weave in the account that follows, but will be summarised separately. The questions are:

To answer these questions, I will organise my explanation into two historical time periods, 1906-69 and 1970-2018, although these are simplified sketches of long and very complicated stories. For the first of these periods, the socio-legal framework in which trade unions grew, developed and operated was one in which the capitalist state—with some notable exceptions—did not typically intervene directly in relations between capitalist employers and unions. In this period, often labelled as that of “abstentionism” in industrial relations literature, governments were inclined to see relations between employers and their workers as an essentially economic matter, rather than one requiring government intervention. This statement needs unpacking. As it stands it is mined with anomalies, as will be explained presently. During our second period, governments and the courts became increasingly interventionist in their dealings with the trade union movement. This period is often referred to as that of “legalism” and brings us up to the present day. The important point here, however, is not simply that this has created a hostile legal environment for trade unions, but that through its links with the Labour Party, the trade union movement as a whole has internalised its logic. Again this will be explained in more detail.

The era of “abstentionism”: 1906-1969

The inter-war social settlement

The Trade Union Disputes Act of 1906 restored the immunity of trade unions from liabilities that would otherwise have arisen from strike action. Previously, in the 1901 Taff Vale judgement the courts had ruled in favour of the Taff Vale Railway Company to force the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants (ASRS) to pay crippling damages following a two-week strike over wages and union recognition. Taff Vale reversed the situation in which trade unions had been treated as self-governing, non-incorporated and loosely-based membership organisations, so not invested with legal “personality” with collective responsibility. The 1906 Act, which annulled the Taff Vale ruling, resulted from the support of trade unions for the new Liberal government of that year. It was to provide the keystone for industrial relations in Britain for the next 60 years.

As already mentioned, caveats are needed before we can proceed. The two world wars that fall within this timeframe saw government regulation of industrial affairs applied extensively across the British economy. One notorious court ruling in 1910, that of ASRS versus Osborne, in which the union’s right to maintain a political fund was overturned, did represent a weakening of the principle of self-regulation. The 1927 Trade Disputes and Trade Unions Act, introduced following the 1926 General Strike, also empowered the attorney general to sequester union funds where rules governing the conduct of strike activity—including rules around mass picketing and the banning of sympathy strikes and political strikes—were breached. Finally, the British state never put aside its willingness to put troops on the streets against strikers when its authority was in question; as evidenced in 1911 during the Liverpool transport strikes and during the 1926 General Strike. The term “abstentionism” then, used to describe the attitude of the British state towards trade union affairs, must be seen as a relative one that at times did not apply. Nonetheless, considering the whole of this period, and compared to what was to follow, the basic immunities guaranteed by the 1906 Act remained largely in place.

This period was one of significant growth in trade union memberships. Between 1910 and 1913 the total number grew from 2.6 million to 4.1 million as new industries and occupations became organised. Between 1915 and 1920, covering the years of post-war economic expansion, the membership figure leapt again from 4.3 million to 8.3 million.18 These years also saw the British state stagger under the impact of major waves of industrial unrest in the approach to, and immediately following, the First World War. It was clear that if the unions could not be suppressed, then some level of accommodation within the legal and legislative system would have to be achieved. Legal immunity from employer prosecutions for damages following industrial action then became a key element in the accommodation of the industrial workforce established in piecemeal fashion in the years following the First World War and developed in full-form following the Second World War. This accommodation was to include wage regulation, national insurance, co-optation of trade union leaders onto boards of industry and improving legislation in the areas of housing, amenities, education, unemployment benefits and health. I will focus briefly on two areas for their relevance to the second part of the analysis being developed here: social housing and poor relief.

Post-First World War efforts to address the acute shortage of housing as soldiers returned home began with the Housing and Town Planning Act of 1919 (the Addison Act). The Act pushed local councils to the fore in implementing ambitious building programmes, supported by central government funding under the auspices of a national advisory committee, the Tudor Walters Committee. In the years that followed, the creation of landscaped “garden estates” on greenfield sites and the building of enormous council estates such as the Becontree estate in Dagenham, became the order of the day. In the early phase of this era, building standards were high and consideration was given to adequate spacing, gas and electricity supplies, good sanitation, privacy and the provision of gardens for recreation and growing vegetables. The 1924 Housing Act (the Wheatley Act) committed the government to a further 15 years of house building aimed at families living on low incomes. The Housing Act of 1930 tasked local councils with extensive slum clearance programmes and the replacement of sub-standard housing with new homes for working class families. Standards of building quality and spacing were to decline as this national building programme unfolded. Nonetheless, these developments, along with rent controls and the provision of improved local amenities such as parks, libraries, public baths and so on, were significant building blocks in the accommodation of the industrial working class in the inter-war years.

Improvements in poor-relief and welfare represented another element in this social settlement. The 1906 Education Act introduced free school meals for children from poor families. The first state pensions were introduced in 1908 under the Old Age Pensions Act. In 1909 labour exchanges were introduced for the unemployed and the 1911 National Insurance Act brought in medical care and time-limited benefits for unemployed workers in “cyclical” industries, those characterised by high rates of job turnover. Between 1918 and 1921 means tested benefits were introduced for the unemployed. The 1929 Local Government Act removed the Boards of Guardians, an element of the old stigmatising system of Victorian poor relief, and replaced them with provisions under local authority control. The Poor Law Acts of 1930, 1934 and 1938 extended public assistance for families in hardship, as well as unemployment relief.

These reform programmes were interrupted by the outbreak of war in 1939. However, the final year of the war, and the years immediately following it, famously saw the resumption of social reform, and now with greater, indeed universal, coverage. The main pieces of legislation were: the 1944 Education Act that provided free universal secondary education; the 1945 Family Allowance Act; the 1946 National Insurance Act; the 1946 National Health Service Act; the 1948 National Assistance Act; and the 1948 Children Act. It also included the Trade Disputes and Trade Unions Act of 1946, which explicitly repealed the punitive provisions of the 1927 Act, so removing the conditions for legal immunity that had been created after the General Strike. The immunity from legal redress by employers following a strike established by the 1906 Act was now restored in full form. Unions operated once more as self-regulating bodies that could call upon their members to break their contracts without the risk to individuals or to the union itself of paying costs to the employer.

The principle of “legal immunity”

The modus vivendi under which the trade unions operated, based on the principles of self-regulation and legal immunity, continued without major challenge for the two decades following the Second World War. However, by the mid-1960s shocks to British capitalism were beginning to fracture the consensus supporting it. The anti-colonial movements that reached their successful climaxes over these two decades meant the loss of empire for British capitalism, and with it the loss of markets and major sources of raw materials. The need to modernise industry and achieve export-led economic growth became an over-riding priority. The idea of “pay-restraint” began to enter government thinking and the editorial perspectives of conservative newspapers. In 1962 a central planning agency, the National Economic Development Council, had already been established by the Conservative Harold Macmillan government to address these emerging challenges. It brought together government ministers, industry heads and trade unions and was chaired by the chancellor of the exchequer. Under its auspices, although court rulings in specific cases of this era revealed a basic hostility towards trade unions on the part of the judiciary and a “legal presumption” against strikes, governmental attitudes towards the unions at the national level were still defined by attempts at persuasion, influence and negotiation rather than coercion or use of the law. Nonetheless, as the 1964 Labour government under Harold Wilson came into office, a major contradiction existed at the heart of economic strategy: the expectation on the part of workers that living standards would continue to rise; and the new government’s need to establish a stable incomes policy.

The result of these tensions was major strikes by dock workers and merchant seamen. Wildcat strikes and spontaneous walkouts over shop-floor disputes became prevalent in many of the newer industries, especially in the car plants. Crucially, what these strikes, as well as the new shop-floor militancy, revealed was the inability of trade union leaders to win cooperation from their members. Attempting to deal with the problems this created for the Wilson government’s employment policy, a Royal Commission into management-labour relations was established. Chaired by Lord Donovan, it recommended a series of sweeping changes including statutory standards for unions’ rules and measures to formalise and strengthen collective bargaining and the enforcement of agreements. Still, however, Donovan fell short of recommending legislative action; the Donovan recommendations, then, remained within the “abstentionist” paradigm.

The Labour government’s response to the Donovan Commission marks the beginning of the end of the “abstentionist” era, and the start of a new one of concerted government intervention in trade union affairs: the era of “legalism”. That response came in the form of the government’s 1969 White Paper, In Place of Strife: A Policy for Industrial Relations proposed by the Labour secretary of state for employment and productivity, Barbara Castle. While accepting the broad terms of the Donovan report, the government also put in place a new statutory power to impose conciliation before any action took place. For a strike to go ahead on an official basis, a union would now have to ballot its members, under pain of fines if this condition was breached. Opposition from the various trade unions and the Trades Union Congress (TUC) to this set of obligations, as well as to government interference in internal union conduct and decision-making processes, was vehement. The unenforceability of the new conditions meant that In Place of Strife was abandoned, and a politically weakened Harold Wilson now went to the country in the general election of 1970, only to lose to the Edward Heath-led Conservative Party.

The era of “legalism”: 1970 to the present

The erosion of legal immunity

The era of legal intervention had already been conceived in a publication by the Conservative Party, Fair Deal at Work, which was heavily influenced by concepts borrowed from federal labour law in the United States. The document proposed far-reaching legal interference in the internal affairs of trade unions and their conduct before and during rounds of industrial action, ideas that fed into the design of the Industrial Relations Act of 1971. A central feature of the 1971 Act was the introduction of legal criteria that had to be met for registration to operate as a trade union. Registration had been required since the Trade Union Act of 1871. However, under the 1971 Act a new National Industrial Relations Court (NIRC) would have the power to revoke registration where a trade union was deemed not to have met the new statutory conditions. Opposition from the trade union movement was again absolute. The creation of the NIRC struck at the very heart of the principles on which trade unions had operated for a century: voluntary self-regulation and legal immunity. It was a step too far even for those union leaders who had supported incomes-control under the Wilson government.

Anger at the 1971 Act fed into the mood of militancy of the early 1970s, and the series of national strikes that rocked the Heath government, leading to its defeat in 1974. The 1971 Act was revoked by the incoming Labour government, again under Harold Wilson. In its place, the 1974 Trade Unions and Labour Relations Act was introduced, which made it explicit that trade unions could not be treated under law as “bodies corporate”, and so were not deemed legal entities for the purposes of court action. The principle of legal immunity was reinstated, and the government embarked upon a period of attempted partnership with the trade unions; the short-lived era of the “social contract”.

Heath’s 1971 Industrial Relations Act had been decisively defeated by the trade union movement. However, in the longer term, and with hindsight, the Act also signalled the direction of successive governments, both Conservative and Labour, in altering the terms upon which trade unionism in Britain was to operate. Over the years of the Labour governments of 1974-6 and 1976-9, the social contract came under severe strain. Under Jim Callaghan (prime minister 1976-9) in particular, financial markets and the conditions of borrowing from the International Monetary Fund brought external pressures upon the government’s partnership-based economic strategy. The result was tension with the unions over wage levels. This, on top of cuts to public services, caused the break-down of the social contract and a new round of industrial conflict by the end of the 1970s; this time between the trade unions and a Labour government. As the social contract crumbled, the language of legal intervention began to reappear.

The period from 1970 to 1979 can be characterised as one of alternation between “legalism”, in the form of the 1971 Industrial Relations Act under the Conservatives, and the restoration of “abstentionism” in the form of the 1974 Trade Unions and Labour Relations Act and the social contract under Labour. However, the outcome of this period of utter confusion and crisis for the capitalist state in relation to the trade unions, was an unholy consensus between the two parties about the need for legal intervention and the use of powerful legislative instruments to diminish their industrial power. It was with the election of the Conservative government under Margaret Thatcher in 1979 that the era of “legalism” in British industrial relations really began in earnest; the “legalism” in which we find the substantive answer to the question, “Why are there so few strikes today?”

Within months of taking office Thatcher inaugurated an intensive programme of legislative acts aimed at the unions, each one designed to further limit their self-regulation and legal immunity. The 1980 Employment Act restricted the ability of unions to take secondary action and reduced lawful picket numbers to six. It also established the legal right to trade union membership for the individual, meaning that strike-breaking could not be a cause for expulsion from a union, so eroding the principle of collective trade union solidarity. The 1982 Employment Act limited the legal requirements placed upon employers arising from recognition of a trade union. The 1984 Trade Union Act established balloting ahead of industrial action as a principle upon which legal immunity was based: so, no ballot, no protection from legal action for damages by employers. That Act also required trade unions to operate on the principle of secrecy for the election of national executive committees.

The 1988 Employment Act further intensified the tendencies towards individualisation, compromising the collectivism of trade unions, with measures enshrining strike-breaking as a legal right; specifically through the creation of a Commissioner for the Rights of Trade Union Members. The 1990 Employment Act removed the right to take secondary solidarity action entirely. It held unions legally responsible for unofficial walkouts unless they publicly disavowed the action. It also allowed for the lawful sacking of stewards involved in such activities. The 1992 Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act removed the right to implement a closed shop (in which all employees are required to be members of the recognised trade union). This latter piece of legislation also included measures to force unions into local consultations in redundancy situations, in place of industrial action.

In 1997, the Conservative government, by then led by John Major, was replaced by Tony Blair’s New Labour with a large majority. What is remarkable about the next 13 years over which the Labour Party held power, is the paucity of labour legislation. The trade unions had seen their room for manoeuvre severely curtailed. Unions could no longer be said to be self-regulating bodies, with a range of internal processes now covered by legislative requirements, undermining the collectivism that they had traditionally represented. “Legal immunity”, the protective bedrock upon which trade union action had been based, was by now a weapon in law, available to employers in dispute situations to hobble the effectiveness of industrial action. With the exception of the 1999 Employment Relations Act, which required employers to recognise and bargain with trade unions where membership thresholds were met, the Labour governments of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown left the legalistic framework for trade unions largely unchanged.

It is true that the Blair years saw the improvement of individual rights in the workplace, including the creation of a minimum wage policy and protections against unfair dismissal. Indeed, these were years that saw a reinforcing of the dependency of the trade union leaders on the Labour Party in office.19 However, this all stood a very long way indeed from the re-establishment of immunities for the purposes of effective industrial action and collective bargaining.

When the David Cameron Conservative-led coalition government came to office in 2010, the “legalism” agenda established by its predecessors of the 1980s and 1990s resumed largely from where it had left off. The most recent piece of anti trade union legislation, the Trade Union Act of 2016 that requires unions to achieve 50 percent turnouts in ballots for industrial action and 40 percent support for strike action by public sector unions in certain services, now makes it more difficult than ever for unions to use their industrial strength. During the summer of 2017, the measures of the 2016 Act blocked action by offshore workers in Unite, London Underground workers in the RMT and council workers in Scotland, members of Unison. Had this Act been in place between 1997 and 2015, 3.3 million workers who took strike action would not have been able to do so.20 The 2016 Act caps a 40-year long legislative agenda that has been aggressively pursued by successive Conservative governments. It has also been tacitly supported by Labour governments over these decades.

The role of the Labour Party

It is this last point, Labour’s support for anti-strike legislation, that needs to be carefully considered to explain fully what has happened to the British labour movement. Without factoring in Labour as the dominant political influence upon the trade union movement, at the levels of leadership and membership, accounts of the low levels of strike action in the UK are skewed towards purely industrial assessments.

Martin Upchurch has provided some very useful observations about the role of the Labour Party in suppressing worker militancy from the 1930s through until the 1960s.21 In my own second contribution to this debate, I did explore the ways in which the years of the New Labour government between 1997 and 2010 saw a strengthening of the link between Labour and the unions, albeit one that was paradoxical and riven with contradictions.22 Nonetheless, with respect to the current situation, explanations of the decline in worker actions often take as their starting point the trade union defeats of the 1980s; so rooting their analysis in industrial psychology. This is one part of the perspective put forward by Joyce, for example.23

As we have seen however, the role of Labourism in reining-in the trade unions began in the 1970s. It is not simply then, that the trade unions today operate in a hostile legal environment (which of course they do); it is that the traditional party of the trade unions, the Labour Party, from this point onwards began to internalise the legislative logic that has created it. To return briefly to that period, the signs of what was to come were there in the attitude of the Labour government of 1976-9 following the breakdown of the social contract. This was revealed in the illustrative example of the Grunwick dispute. Occurring between 1976 and 1978, “Grunwick” was a struggle for trade union recognition by predominantly East African Asian women workers, led by their chief steward, Jayaben Desai. It is relevant here because of the way in which the Labour government of that time led by Jim Callaghan with Merlyn Rees as home secretary, reeling under the impact of public sector strikes, sought to prove to the British establishment that they could do what Heath had been unable to do: control the unions. To this end, with the connivance of the TUC under the leadership of Len Murray, both secondary action and mass picketing in support of the Grunwick strikers were forcefully suppressed, with the use of indiscriminately heavy-handed methods by the Special Patrol Group of the Metropolitan Police.

So the anti-strike stance of the Labour leaderships during the 1980s, evident during the years of the Wilson government of 1964-70, became cemented during the final years of the Callaghan government of 1976-9. This strike-averse mentality was transmitted into the perspectives and practical orientations of trade unions themselves, to varying degrees, over the course of the 1980s. This, of course, intensified following the defeat of the miners’ strike in 1985, not simply because of the demoralising psychological experience of defeat, but because the strike was the last major example of an industrial battle fought against the legalistic terms upon which such disputes were now to be conducted. While the depressive effects of the defeat were felt long after the strike itself then, the reluctance of growing sections of the official trade union movement to lead or endorse action beyond the most limited forms, preferring legal redress through the courts wherever possible, in fact preceded it.

When Labour eventually returned to power in 1997, the trade union movement had internalised as norms the limitations upon its ability to act in defence of members. By the end of the 1980s the unions had already moved away from a dominant rhetoric of industrial collectivism based on legal immunity, to one of trade union and individual workplace “positive rights”.24 In effect this represented an acceptance of the “legalism” that had so effectively undermined their industrial power.

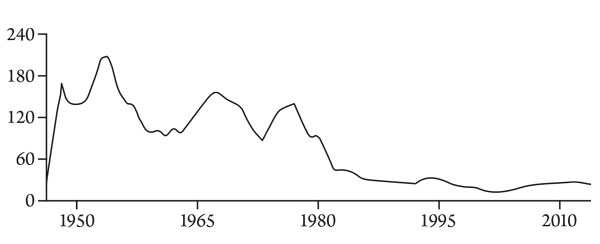

The loss of social protection

The establishment of “legalism” in the state’s dealings with trade unions was one aspect of a larger dismantling of the class settlement of the inter-war and post-Second World War era. Another major aspect was the attrition of the welfare state down to minimal levels for unemployed and low-paid workers and their families. The welfare state had provided the foundation upon which the established system of industrial relations operated, creating a social framework within which conflicts occurred. The removal of the social protections it had afforded saw an intensification from 2010 onwards with the return of the Conservatives to office. The Welfare Reform Act 2012 and the Welfare Reform and Work Act 2016 introduced major reductions in government spending for the poor and a swathe of new conditionalities for, and caps to, benefits, freezes to tax credits and removals of crisis payments. With respect to social housing, the Housing Acts of 1980 and 1988 in particular created powerful pressures against council tenancies, through a range of marketising measures that removed council housing from local authority hands. The result of these measures, as well as the collapse of council house building since the 1950s, has resulted in a rapidly expanding private rented sector, characterised by soaring rent levels. On current trends, by 2025 half of all workers in the 20-39 age range will be renting their homes.25

These elements of the welfare state have been reduced to a residue of what they were in the 1970s. This has been part and parcel of the erosion of the social quid pro quo that once mitigated the risks of taking action for activists and ordinary trade union members alike.

Figure 2: Number of social homes built in England since 1946 (thousands)

Source: Shelter, 2017

Answering the questions

Returning to the two questions with which we began, we can now give our answers.

First, the conditions within which trade unions operate are obviously far more difficult today than they were in the 1970s, the heyday of trade union strength in the post-Second World War era. However, it is not simply that the external environment has become more hostile. It is also that because of its relationship to the Labour Party, the trade union movement has adapted to those changed conditions through the absorption of the logic of “legalism” that is the very root of the problem. In the 1970s trade union leaders were prepared to stage major actions against anti trade union legislation because it struck at the fundamental principles of how they had operated for a century, as self-regulating bodies, with legal immunity when their members broke their contracts during strikes. Today so many conditions apply to the principle of immunity that the risks of being in breach of them and so bringing the danger of significant damages being exacted by employers, are high. In this situation all trade union leaders are extremely cautious about any type of action that might run out of their control and will avoid strike action wherever they can.

The risks attached to local strikes are relatively low, because of their small size (a function of the number of members involved, and the number of days the action lasts for). It is national strikes that present the problem; because of the numbers of members who can potentially take action, and therefore the scale of damages that might have to be paid. So where national strike action is difficult to avoid, trade union leaders will limit it to very short periods, often of just one day. This is in order to limit potential damages; but more importantly so that strike dynamics do not emerge that allow local activists to achieve strategic influence over events. The effect of these profound changes to the character of the British trade union movement has actually been to strengthen the position of trade union leaders with respect to their members. Many walkouts and strikes of the 1960s and early 1970s occurred because trade union leaders could not control their members. Today that control, political challenges aside, is secure. It is also something that union leaders will not surrender easily.

This is the reason why no union leader will lead struggles on the model of the early 1970s. It is a type of action long ago abandoned; not simply in its scale, but in its socio-legal form. This is also the historical meaning of the peaks and troughs of trade union action between 1970 and 1985: a “push-pull” struggle over the very nature of industrial relations in the UK. Its final conclusion was the end of an industrial (as opposed to only political) left at the national level in the British trade unions.

Second, the reason that workers do not tend to act independently of the trade union officials is that no safe mechanism for doing so exists. This is where the “removal of the strike weapon” has its place, along with other types of proximal cause. It is one aspect of the larger issue of the diminution of the power of local leaderships resulting from the strengthening of bureaucratic machinery inside trade union organisations. The conditions for immunity now mean that where local members walk out unofficially, their union must publicly repudiate that action. The union must also take no action to support members who are sacked following an unlawful strike, on pain of loss of immunity. Stewards can be lawfully sacked for leading unofficial walkouts, without being able to look for support from their union, other than seeking legal redress for unfair dismissal or trade union discrimination. In the event of loss of employment under such circumstances, there will be little or nothing in the way of state welfare support for the sacked worker or activist and their family.

So, the aggregate result of the erosion of legal immunity combined with the erosion of social protections is that while union leaders are unprepared to defy the law, and so are utterly reluctant to provide any type of effective leadership, worker-members of unions are unable to take action that is independent of them, ie unofficial. To do so would mean taking enormous and, for most, unacceptable risks in unlawfully breaking their contracts. It would mean facing the very real risk of loss of employment, quickly followed by loss of home where secure tenancies no longer exist.

Where is the reprieve?

The election of Jeremy Corbyn as leader of the Labour Party in September 2015, and the strong Labour performance in the election of June 2017 under his leadership, has cast many of the questions raised in this debate in a new and interesting light. Corbyn, himself a former trade union official, has repeatedly and sincerely pledged his support for the trade union movement. If elected, he has promised to repeal the punitive 2016 Trade Union Act and the thresholds it applies for strike ballots. He has also indicated his support for “sympathy strikes” and said that a Labour government under his prime ministership would legalise secondary industrial action. These pledges are very welcome to trade union activists. Actually, since 2005 the formal positions of both the TUC and the Labour Party have been to repeal the anti trade union laws. In 2010 John McDonnell MP tabled a private member’s bill in parliament calling for a Trade Union Freedom Bill that focused on notice periods for ballots and the abuse of technical anomalies by employers to prevent strike action. In 2013 the Campaign for Trade Union Freedom was launched from a merger of the Liaison Committee for the Defence of Trade Unions and the United Campaign To Repeal The Anti Trade Union Laws. The problem is not lost on the trade union lefts, or the current left Labour Party leadership.

However, there are two things to consider. First, restoring the ability of trade unions to use their industrial power at previous levels would require the full return of self-regulation and legal immunity. At least ten pieces of anti trade union legislation, from the 1980 Employment Act onwards, would need to be repealed. Specifically, without the removal of the ballot as a statutory requirement ahead of strike action and the interference in trade union democracy that it represents, the proposals for repeal that have been tabled so far remain firmly within the legalist paradigm; and so fail to address the problem at its root.

Second, the trade unions themselves would have to change the way in which they behave. Here the problems are considerable. Trade union leaderships, left and right, enjoy a greater degree of control of their memberships than ever before. The changes needed will not be forthcoming from a bureaucracy that is unprepared to relinquish that control to local stewards and activists, on the model that prevailed on the shop floors of the Cowley, Halewood and Dagenham car plants in the 1960s, for example. Whether unions move in that sort of direction, and whether a new left Labour government, would really begin the job of fully dismantling the legislative framework that is so hostile to effective trade unionism, depends upon whether workers themselves move into action.

And there’s the rub. In this “which comes first?” quandary, it may be that the political inspiration of Corbynism raises the confidence of ordinary trade union members to turn out well in industrial ballots and begin to vote comprehensively for strikes, hitting and exceeding the thresholds needed. The example of postal workers, members of the Communication Workers Union, voting 89 percent to strike on a 73 percent turnout last summer, provides a dramatic illustration of this possibility; despite the union’s failure to launch strikes. However, without workers moving into action the effect of Corbynism may well be to make the trade unions more dependent on the Labour Party, in ways that perpetuate their passivity; the “wait for Labour” and “don’t rock the boat” mentality that has historically bedevilled the trade union movement.

In the meantime, the contradiction between the impositions of pay restraint, the pain of austerity, the erosion of the welfare state, etc, and the passivity of the trade union movement, continues to intensify. Of course, the class struggle does not stop. It is also important to say that none of what has happened has been inevitable. There have been points at which the process, in some of its aspects at least, was preventable and could possibly even have been reversed: the pensions dispute of 2011 being the most recent, in my view. However, the assault from the state grinds on and employers become more aggressive.

On our side, there are always strikes in localities, and national strikes will also occur where unions achieve the thresholds required to strike within the law. Membership figures still hold up, despite the woeful performance of national leaders. Some trade unions, such as the National Union of Teachers with “social movement unionism”26 and Unite with “community unionism”, are trialling new ways of organising and looking at traditions of struggle from around the world. Others have opened up discussions to stimulate fresh thinking around industrial action, for example, the UCU commission into industrial action and bargaining strategies.

Workers do find creative ways to react to employers’ encroachments. Indeed, a culture of grassroots resistance has characterised the decades over which our problem has become increasingly apparent. Unions have made good use of social media for organising, solidarity and information sharing with activists’ lists, online events and so on. With extraordinary tenacity and irrepressible determination, activists continue to do what they can using traditional methods and with the lawful strategies still available: fighting hard for high turnouts and “Yes” votes for action; building around the local disputes that occur; fighting inside the unions to win action that is coordinated between different unions; building non-strike solidarity with striking workers through collection sheets, invitations to speak and so on. Even within very bureaucratically controlled national strikes there are brief moments when the official hand slips and loosens it grip, opening up spaces for activist initiatives; the “rank and file moment”.

We should keep in mind too, that with each new attack nationally or locally, and with every cut to a service or a type of welfare support, new triggers for acts of resistance are created. Indeed, it is interesting that in recent years, even against the rather bleak background that this article has described, there are breaks in the industrial situation that conjure up the possibility of the genie of worker militancy escaping from the bureaucratic bottle. We do see cases, for example, in which workers take action outside of the law, and sometimes in conscious defiance of it; especially where there is a tradition of doing so in a specific union. In 2017 a series of unofficial walkouts by postal workers took place at local sorting offices, including those at Milton Keynes and Luton in support of two union reps and at Bridgwater in Somerset in support of a disabled colleague. The initial walkout by cleaners at the Royal London Hospital was effectively a wildcat action. Teaching staff on fractional contracts took unofficial action at the School of Oriental and African Studies over pay for marking time—successfully. Evidently, where workers walk out unofficially in sufficient numbers and with collective determination, it can be difficult for employers to respond with victimisations.

A survey of strikes over the last ten years reveals in fact a peppering of actions taken outside of legal protection, and often ending in employer concessions. In 2009 we saw a brief rash of workplace occupations by workers threatened by company closures. Finally, in an intriguing subversion of the much employer-abused category of “self-employed”, in new industry sectors—the gig economy—workers have taken action outside of the law, though with a de facto immunity from prosecution precisely because they are not legally defined as “employees”. In 2016 couriers for Deliveroo did just this, very effectively. Indeed, this area has proved a fertile ground for new types of trade unionism. An example here is the Independent Workers Union of Great Britain, which has conducted industrial campaigns around issues affecting taxi drivers, cleaners and security guards.27 The “legalism” of the trade unions in Britain, though unmistakeably the dominant paradigm, is not without its own contradictions and fissures.

As workers’ wages are held down and as working conditions are eroded, the grievances, resentments and frustrations continue to build; and the stresses and strains do continue to accumulate. There is also the crisis and uncertainty for the British state caused by the impact of Brexit. There is a palpable atmosphere of unease in British politics, and a sense of the ground shifting beneath our feet. Something, we feel, will blow; we just can’t say what, how or (unfortunately) when. It’s unpredictable. What we can predict, however, is that when something does happen, it will be rather more chaotic, high risk and dramatic than the types of action familiar to us from the torpid world of official trade unionism.

Practical conclusions: “expecting the unexpected”, building networks and the need for a horizontal perspective

To say that “things are unpredictable” cannot by itself provide the basis for an industrial perspective inside the unions. That would be a recipe for a fatalistic waiting game; a non-action that is unacceptable to activists generally, and especially revolutionary activists. However, the frustration within the working class as potential struggles are suppressed is cumulative and real. If this frustration is not expressed in official union actions, it will find other outlets. To indulge our geological metaphor for a moment longer, it results in stresses and strains that will produce breaks in the normal pattern of staged industrial action controlled by national officials. It is a journalistic cliché now, of course, to say that unpredictability is the “new normal”: the EU referendum result, the near-miss of the Scottish referendum and Corbyn’s popularity in the June 2017 general election have all been surprises that in different ways expressed deep-seated working class discontent, not articulated by long-established political forms. This same discontent will have its industrial moment too—and in ways that are unpredictable. If correct, this assessment has serious implications and needs to be properly thought through.

For our own activism, there are, I believe, two possible scenarios. We can continue as before, working hard to pull trade unions leaders to the left, talking about defying the law, seeking to replace right wing leaders with left wing leaders (who would then face the same objective limitations on their ability to act that we have considered here) and so on. Alternatively, we can change direction in perspective and organising focus, in ways that maximise our position for any breaks in the situation that occur in the coming years, and our ability to influence the direction of the actions that result.

The first of these I characterise as a “vertical perspective”. Here, mired in the practice of legalistic trade unionism, the energy of trade union activists is consumed by the world of national committees and campaign groups, industrial sub-groups, national executives, regional executives, annual congresses and so on. Workplace activity and positions then come to serve this as the main field of action; so the individuals involved become the (often quasi-legal) experts within their own branches, always reporting from this “other world” to the eyes and ears of local memberships at union meetings. As we know, this is the result of the deeply compromised situation in which we find ourselves; and it is admittedly hard to see how we can avoid these consequences entirely, given the realities we face.

However, we surely have to keep in sight what we are: Marxists in the workplace. At the heart of Marxism lies the principle of the self-activity of workers. That means that workers develop an ability to act in their own right and independently of reformist and bureaucratic leaderships. In non-revolutionary periods this usually occurs in the moment of action and is brief. As historical situations develop, however, this self-activity can take on more sustained expressions, with rising collective confidence, articulating organisational forms, awareness of historical lessons, etc. It is in this sense that Marx called the trade unions “schools of socialism”. This does not mean trade unions can be revolutionary in normal times; they cannot. However, trade union struggle fertilises the ground from which workers can move towards an independent class consciousness, and indeed an ability to act in their own right. No amount of casework, organised through representation on behalf of a union member, will achieve that. Indeed, if this is all we do, our industrial perspectives lack any horizon informed by the possibility of self-activity on the part of workers; and without that we are not really Marxists in the workplace, in an objective sense. The danger is that we become bureaucratised ourselves, and locked into positions and organisational processes that will block our ability to relate to “breaks” when they occur. Worse, our activism—particularly around casework—morphs all too easily into an adaptation to models of “service unionism” that are promoted by the right in the trade unions.

The alternative I characterise as a “horizontal perspective”. In this scenario, the great majority of our work goes into building within and between workplaces. At present we do talk of “networks” but only in the most abstract way. In fact there are many types of network. So networks can be built within single workplaces, where they are large enough. They can be also be built between workplaces within the same industrial sector across a city or geographical region. Networks may move in and out of focus according to the issues that come and go: strike solidarity; struggles for reinstatement; the whole range of trade union political campaigns; etc. Indeed, a culture of networking can emerge in which activists spontaneously come together around specific struggles. Some activists will network in this way regularly, so becoming the node of a network: others will be involved more episodically. However it is done, it will take proper application, theorisation and determination. Networks are more than simply relationships between activists who have been around in a locality for a long time. They must be built as an organisational form with a committed perspective. They will not emerge as a local side effect of vertical initiatives. To become successful, they need to be consciously built; making a horizontal perspective the primary field of action. Over time this will allow far greater numbers of activists to become involved in industrial organising and will place us in a much better position for the types of struggle we are likely to see in the years ahead.

Whatever the difficulties involved in building and sustaining various types of industrial network, we would then be operating with a perspective centred, not simply on the grind of trade union duties we perform in our respective branches and the positions we achieve in the union machine, but on the industrial power of workers to take on capitalism.

Mark O’Brien is a socialist researcher based in the city of Liverpool.

Notes

1 The ONS produces an annual “Labour Disputes in the UK” report each May. The May 2017 report gives the figures for 2016; the most recent complete data set. The next updated report for disputes occurring in 2017 will be published in May 2018.

2 Office for National Statistics, 2017.

3 Collinson, 2017.

4 Standing, 2014.

5 Davidson, 2013.

6 Hardy and Choonara, 2013.

7 O’Brien, 2014.

8 Joyce, 2015; Joyce, 2017.

9 See Joyce, 2015, p141.

10 Morgan, 2016.

11 Lyddon, 2015.

12 Lyddon, 2015; Darlington, 2016.

13 Upchurch, 2015; McGarr, 2016.

14 Upchurch, 2015.

15 Joyce, 2015.

16 For example McGarr, 2016.

17 Upchurch, 2015; Darlington, 2016; O’Brien, 2015.

18 Wrigley, 1991.

19 O’Brien, 2015.

20 Darlington and Dobson, 2015.

21 Upchurch, 2015.

22 O’Brien, 2015.

23 Joyce, 2015; Joyce, 2017.

24 Syrett, 1998.

25 O’Brien and Kyprianou, 2017.

26 Stevenson and Little, 2015.

27 Go to https://iwgb.org.uk/

References