Radicalism is not a term that adheres easily to the 46th president of the United States, Joe Biden.1 Biden is a traditional centre-right Democrat, a long-standing proponent of welfare cuts, a former supporter of George Bush’s 2003 invasion of Iraq, and vice president during the disappointing Barack Obama administration. Nonetheless, there has been surprise in some quarters at the measures taken by the incoming president during his first few months in office. As Edward Luce put it in the Financial Times:

Whether you ask Americans or foreigners, liberals or conservatives, Joe Biden’s presidency strikes most people as surprisingly radical. In his first 100 days, Biden boosted US spending by roughly 15 percent of gross domestic product, embarked on a charm offensive with allies, reclaimed US leadership on global warming and put Donald Trump in the Mar-a-Lago rear-view mirror. Some of Biden’s more extravagant backers liken him to Franklin D Roosevelt, whose opening spell in 1933 laid the foundations for the US welfare state and slayed the spectre of American fascism. It is hard to find a more abrupt presidential shift than from Trump to Biden.2

The Guardian’s Jonathan Freedland went further:

The Biden presidency has easily secured the right to be described as radical… He is overturning four decades of hostility to big government…and the US is engaged in a massive wealth redistribution programme… The true radical is the one who wins power and uses it for good.3

Even Bernie Sanders, the independent socialist senator for Vermont who is a figurehead for the left in Congress, muted his criticisms during Biden’s early months in office. Sanders summed up his relationship with Biden for CNN with what reads like the world’s worst marriage vow: “We’re going to have our differences, but I ultimately trust you and you’re going to trust me. We’re not going to double-cross each other. There will be bad times, but we’re going to get through this together”.4

Biden has announced substantial stimulus and infrastructure plans. A bill for an initial $1.9 trillion stimulus was signed by the president in March this year. A further $1.2 trillion plan to fund roads, public transport, the electricity grid and internet access over eight years was agreed in principle by senators from both major parties in late June. An additional “reconciliation bill”, worth roughly $6 trillion, is being drafted by none other than Sanders, which is one of the reasons for his relative enthusiasm for Biden.5 This bill is designed to provide funding for the Democrats’ programmes for education, welfare and climate change amelioration.

Along with these measures, Biden has promised to reverse the Trump administration’s decision to remove the US from the Paris Climate Agreement, pledging to halve the US’s greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 and put the country on the path to zero net emissions by 2050. He has also announced plans for a global scheme to impose minimum taxes on multinational companies and end a situation in which 91 Fortune 500 companies paid no taxes at all in the US in 2018. In addition, he has spoken more generally about addressing the inequality in US society.

How radical are Biden’s measures and what do they tell us about the shape capitalism is taking in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic?

From the outset, a few notes of caution are due. There is no guarantee that the most ambitious plans, supported by progressives in and around the Democratic Party, will be realised. Biden initially claimed his aim was to pass the reconciliation bill alongside the $1.2 trillion plan. In late June, the president stated bluntly of the latter bill: “If this is the only thing that comes to me, I’m not signing it. It’s in tandem”.6 However, a couple of days later, under pressure from senate Republicans, Biden performed an abrupt U-turn, saying:

At a press conference after announcing the bipartisan agreement, I indicated that I would refuse to sign the infrastructure bill if it was sent to me without my Families Plan and other priorities… That statement understandably upset some Republicans, who do not see the two plans as linked… My comments also created the impression that I was issuing a veto threat on the very plan I had just agreed to, which was certainly not my intent.7

It is not just Republicans who are likely to oppose the larger package. Of the $6 trillion spending plan, left figures such as Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez envisage that up to $2.5 trillion will be funded by tax rises imposed primarily on businesses and the wealthy. Democrats to their right are likely to baulk at these measures.8 Opposition from both Republicans and mainstream Democrats is not simply a barrier to passing significant reforms through Congress but also a useful tool to discipline the progressives on the left of the Democratic Party. Biden was happy to use these progressives to add vibrancy to his otherwise lacklustre election campaign but in office they represent a potential nuisance. This is particularly so as it becomes clear that Biden is perfectly willing to renege on measures on which he campaigned—including a much-touted “public option” for healthcare insurance, student loan cancellation and lower prescription drug costs.9

Insomuch as the more ambitious plans do come to fruition they would in effect shift the US closer towards levels of social spending already in place in several major European powers. Publically funded social expenditure in the US was just 19 percent of GDP in 2019, compared to 31 percent in France or 26 percent in Germany.10 Similarly, the emissions pledge puts the US on a similar, if slightly less ambitious, track to the European Union, which recently promised to cut emissions by 55 percent by 2030—whether this actually takes place and whether it can prevent catastrophic climate change are, of course, more pertinent questions.11 The global tax plan was, according to the Financial Times, met by “a collective yawn” from stock markets, due both to the difficulties of forcing countries to adopt the measure and the belief that “the extra tax raised…would be little more than a rounding error in most of the companies’ accounts”.12

Nonetheless, the measures announced by Biden represent a rhetorical shift from the administration of the world’s pre-eminent power and a series of policies that, if not matching the rhetoric, remain significant. Underlying these changes is a reconfiguration of the relationship between state and capital—one that, it is argued here, reflects cumulative changes to capitalism over recent years.

State and capital

One feature of the political economy associated with this journal is its emphasis on the integral role of the state within the logic of capitalism. States pre-date the capitalist system, emerging with the earliest class societies and reflecting, as Lenin put it, the “irreconcilability of class antagonism” between those who produce the wealth of society and the rulers who exploit them.13 However, these states were taken up and transformed as successive class societies emerged, culminating in the formation of specifically capitalist “nation states”. These are based on the idealised notion of citizens across a territory sharing a common language and expressing loyalty to a given centre of sovereignty. Critically, the formation of nation states reflects the clustering of markets and producers, and once formed these states seek to create the conditions for further developing capitalism on their terrain and expanding their influence externally. This puts pressure on ruling classes elsewhere to create their own modern state machinery capable of doing the same.14

The fact that these are capitalist states does not mean that they are directly run by, or simply the passive instrument of, the capitalist class. Rather, there is what Chris Harman calls a structural interdependence between capital and the state.15 Capitalists seek the support of their state in creating, reproducing and enhancing the conditions for the continued exploitation of workers and accumulation of capital. That involves not simply the defence of capitalist property through repression of the exploited and oppressed, but also creation and maintenance of the infrastructure and institutions—roads, education systems, systems of laws and so on—required by capital. Those running states may do all manner of things to the detriment of capital or in opposition to particular capitalists but the autonomy of the state has limits. States depend on the health of capital based within their territories to provide them with the resources they require, including the tax revenue on which the state machine relies. Those presiding over states also require capital to engender sufficient economic vitality for them to secure a base of support.16

Within this general account, the specific interrelation of state and capital varies in different geographical and historical contexts. An extreme case, in which the state was able to assume the traditional role of the capitalist ruling class, is presented by the Soviet Union. This operated as what Tony Cliff called a “bureaucratic state capitalism”.17 This arose under conditions in which private capitalists had largely been dispossessed due to the 1917 revolution. As the revolutions that followed the First World War were, beyond Russia, contained and defeated, the Soviet Union found itself isolated amid a world of capitalist states. The civil war and associated economic dislocation in the wake of the revolution decimated the Russian working class and the organs of class rule it had created in the revolution. Under these conditions, the party bureaucracy, with Joseph Stalin at its head, increasingly substituted itself for working class rule. By the late 1920s, this bureaucracy was able to establish itself as a ruling class in its own right in relation to both the peasantry and the working class.18 This ruling bureaucracy presided over the economy, directing its resources internally as if it were a single gigantic capitalist enterprise.

Within this state capitalism, as in a capitalist factory, there was what Cliff called a “partial negation” of the law of value.19 The internal departments of a factory do not trade with one another through market exchange. Yet, as with a factory, the Soviet economy was subject to external pressure that conditioned its inner workings. In the case of firms in traditional capitalism, this pressure is mediated through markets. In the case of the Soviet Union, inter-imperialist rivalry compelled the state capitalists to develop an industrial base and military capacity that could rival that of Western capitalist states. State capitalism in the East came to mirror, in crucial ways, the capitalism of the West. Exploitation of workers and the subordination of consumption to the accumulation of capital shaped the dynamics of the Soviet Union along with the regimes it helped establish in Eastern Europe after the Second World War.

Cliff’s path-breaking analysis is not simply of historical interest. There are three important ways in which the theory developed by pioneers such as Cliff, Harman and Mike Kidron can be generalised.20

Many states

First, as Colin Barker emphasised, we can only conceive of the capitalist state in the context of a “world system of states”. The social relations of capitalism consist of “vertical” divisions, between capitalists and the workers they exploit, but also “horizontal” division between competing capitalists. As states and capitals intermesh, we should expect to see a similar logic play out in the state system—in which the state does not simply act as “an apparatus of class domination” but also engages in competition with rival capitalist states on the international terrain.21 Indeed the whole logic of capitalism as a system of inter-imperialist rivalry relies on this insight as the process of inter-state competition becomes “subsumed under that between capitals”.22

States are compelled to follow this logic whether they are superpowers, operating on a global scale, such as the US; major powers such as Britain, France or China; “sub-imperialists”, such as Turkey, Iran or Qatar, carving out their own regional sphere of influence; or even those states near the bottom of the hierarchy seeking to preserve their independence and to enhance their position in this system.23

The state capitalist phase

A second generalisation is that the tendency towards state capitalism, taken to its logical extreme in the Soviet Union, was reflected elsewhere. This was foreshadowed by the conditions created by the First World War, returning during the slump of the 1930s. State involvement in the economy took a modest form in the US under the New Deal. It occurred far more dramatically in Nazi Germany from the mid-1930s, where state direction of the economy, with the complicity of much of large capital, became the norm.24 Other late-developing capitalist powers such as Italy and Japan followed suit. As Harman writes: “‘Planning’ came to be seen as the only real alternative to repeated crises and was adopted in one form or another by many of the weaker capitalisms… Even in Britain there was a certain trend towards state intervention under the Tory governments of the 1930s”.25

The Second World War radicalised this tendency as states mobilised for “total war”. Although in the West there was a partial retreat from these methods when the war ended, levels of state expenditure remained at higher levels than prior to the war effort. Planning, state control over some sections of industry, an expanded role for the state in creating infrastructural and welfare systems, and some degree of autarky from the global economy appeared effective means of promoting growth as the long post-war boom began to gather pace. This was also the case for the Soviet Union, where the economy saw industrial output increase seven-fold from the mid-1940s to the mid-1970.26 The state capitalist model of development exerted a huge influence not just over advanced economies but, in particular, among late-developing capitalisms in the Global South, including those recently liberated from colonial rule.

With the ebbing of the post-war boom this method of promoting capitalist development started to reach its limits. The pattern of declining profitability that drives capitalist crises began to reassert itself, leading to a series of major recessions from the 1970s. The Keynesian orthodoxy that had emerged in the West during the boom appeared incapable of reversing these crises.27 Meanwhile, countries with the highest degree state intervention appeared to be doing even worse, with the Soviet Union and its allies in Eastern Europe falling into terminal decline by 1989-91. This reflected the extent to which these economies had blunted the traditional mechanism of restructuring through crises, leaving them glutted with stagnating large-scale investment. As their ability to compete with rivals declined, they were forced to divert an ever-increasing share of output towards accumulation, deepening their stagnation. The problems were reinforced by the limited access these state capitalisms had to the wider global system. This system had transformed itself over the period of the long post-war boom, with a far greater degree of capitalist integration, encompassing flows of finance, trade and cross-border production systems.28

These changes underlay the shift towards widespread acceptance of neoliberal ideologies and the implementation of neoliberal policy regimes in the wake of the crises of the 1970s. The new approach combined efforts to restore the fortunes of capitalism by weakening workers’ organisation, to support cross border trade and financial flows through deregulation, to promote fiscal and monetary stability, and to mobilise the state to bolster supposedly self-regulating markets as the prime mechanism for distributing resources and to insulate them from popular pressure.29 In the Global South this shift often took a more dramatic and painful form, through economies’ traumatic integration in global market. This was undertaken with varying degrees of enthusiasm or acquiescence from sections of their ruling classes, combined with the forceful imposition of the “Washington consensus” through the interventions of the International Monetary Fund and World Bank.30

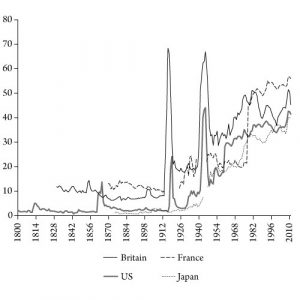

Whatever the rhetorical claims of neoliberalism, the turn taken by capitalism from the 1980s involved not so much a decline in the scale of state intervention as its redirection. State expenditure rose or remained at similar levels in most advanced economies (figure 1). However, the growing integration of capital across borders through the formation of multinational firms and the flow of finance between markets complicated matters. To a far greater degree than in previous periods, the interdependence of state and capital came under strain. Some big multinational firms formed relationships with a range of different states, while states found it harder to disentangle their “own” capitalists from those simply operating within their borders. This tension has been reinforced by the growing antipathy towards the neoliberal policy regimes that had by the 1990s become the default not just for politicians of the centre right but also much of social democracy. The resulting “constellation of ideologies”, broadly aligned with neoliberalism, has since taken, as Susan Watkins puts it, “a battering” from so-called “populist” forces to the right or left.31

Figure 1: State expenditure as percentage of GDP

Source: IMF historical public finance dataset

The state as part of capitalism

This leads to the third point made by the International Socialist tradition with regard to the state. Although it is perfectly legitimate for those on the left to wish to weaken market imperatives and resist or reverse privatisations, state direction of the economy is not, in itself, socialist. Illusions in the state are widely held on the left. That is most obviously the case within the social democratic tradition, in which the state is seen as a neutral instrument that can be captured to reform capitalism and reconcile class antagonisms. For those influenced by Stalinism, the planned economy of the state capitalist era is the hallmark of a socialist society. Similarly, models of development in the Global South premised on state direction of the economy are often conflated with socialism. Even among orthodox Trotskyists, the identification of the Soviet Union as a “degenerated workers’ state” and of the Eastern European regimes as “deformed workers’ states” muddied the water on this question.32

Within Marxist theory, interventions in the major debates on the state in the 1960s and 1970s often took as their starting point the need to overcome a “reductionism”, in which the state was seen as straightforward manifestation of capitalist power, but ended up licensing left-wing versions of reformism. For instance, in the celebrated debate between Nicos Poultantzas and Ralph Miliband, both ended up supporting some combination of extra-parliamentary mobilisation and struggle within the capitalist state.33 More recently, David Harvey, one of the most prominent Marxists today, has argued that the privatisation of state assets and the collapse of Stalinism represent a latter-day “enclosure of the commons”, analogous with the appropriation of common land to create capitalist farms early in the history of capitalism. He associates this with the assimilation of an “outside” into which capitalism is encroaching.34 In reality, the processes he describes are much better seen as a restructuring of the balance between state and private capital within the system.35

With these points in mind, what should we make of recent reconfigurations in the relationship between state and capital reflected in the pronouncements of the Biden administration?

Reconfigurations 1: the US and China

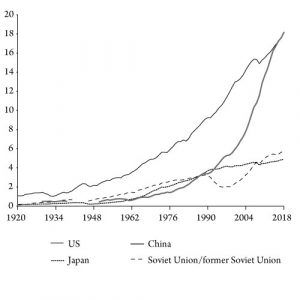

One inescapable feature of the pronouncements by Biden is the inter-imperialist context in which he locates them. China, in particular, is depicted as a threat to the US’s status as the sole superpower. Chinese military expenditure remains only a third of that of the US, unlike Soviet spending, which, at the height of the Cold War, was similar to that of the US.36 However, China’s growth means that, relative to the US, it represents a far greater economic challenge than either the Soviet Union in the 1960s or Japan in the 1980s (figure 2). Although the use of “purchasing power parity” to estimate GDP exaggerates the scale of China’s economy relative to that of the US, even at nominal values the former now boasts an economy two-thirds the size of the latter.

Figure 2: GDP (trillions of 2011 $s) Purchasing Power Parity measures

Source: Maddison Project Database 2020

This preoccupation with China is not new. Think tanks such as the Project for a New American Century that informed the 2001-09 Bush administration were fixated on the emergence of potential rivals such as China. The 2003 invasion of Iraq was motivated by, among other things, a desire to remind countries such as China of the US’s military might and to tighten Washington’s grip of the “oil spigot” at the expense of its competitors.37 With the failure of Bush’s wars, the Obama administration sought to extract itself from what had become a quagmire in the Middle East and to “pivot” to Asia, projecting a stronger military presence into the region and securing diplomatic and trade agreements, in particular the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), with regional allies in order to hem in China.38 Donald Trump’s presidency had broadly similar aims, even if the means it used were rather different. Proposed deals such as the TPP were torn up early in his presidency, and a more confrontational, less multilateral approach—based around tariffs and other measures to restrict trade—was applied.39

Although Biden ostensibly offers a chance to “reset” US-China relations after Trump’s presidency, he has not fully broken from his predecessor’s assertiveness. Indeed, some US firms have expressed consternation that many of Trump’s trade barriers remain in place several months into the new administration.40

The enhanced role for the US state reflects this continued inter-imperialist rivalry. The US has, again, contrary to the nostrums of neoliberalism, long had a substantial, sometimes decisive, role in bankrolling, directing and coordinating its capitalists. As Mariana Mazzucato details in her aptly named book, The Entrepreneurial State, the creation of market leaders in areas such as technology and pharmaceuticals has rested heavily on public investment, spin-offs from work for the military and other state agencies, and government-funded research.41 These efforts will now become more explicit. According to Brian Deese, director of National Economic Council, which advises the president on economic matters:

This crisis and this recovery expose a long-term hollowing out of our country’s industrial base, which happened over decades… We should be clear-eyed that China and others are playing by a different set of rules. Strategic public investments to shelter and grow champion industries is a reality of the 21st century economy. We cannot ignore or wish this away. That’s why we need a new strategy… Our view is this strategy needs to be built on five core pillars: supply-chain resilience, targeted public investment, public procurement, climate resilience and equity.42

China is not simply a powerful competitor to the US. Its rise also increases the weight within the global system of economies in which the state openly plays an active, strategic role in directing industry. The roots of this lie in China’s long-term development. After the Chinese Revolution of 1949, China incrementally adopted a version of Stalin-era state capitalism. However, by the 1970s, the country’s rulers had become painfully aware of the failure of China to “catch up” with the West or even neighbouring Asian countries. China managed to avoid the fate of the Soviet Union—stagnation and collapse, followed by catastrophic neoliberal shock therapy.43 Instead, the country embarked on a strategy that involved a number of measures: gradually removing price controls in order to strengthen market mechanisms; creating new industrial centres in coastal and rural areas, often under the authority of local or regional rather than central government; and attracting foreign investment that helped it to conquer export markets in key areas such as electronics assembly.

These methods have integrated the Chinese economy into the world system, and have allowed it to move beyond simply being a gigantic assembly platform for iPhones or laptops towards developing its own industrial base. However, the Chinese state retains a considerable role in the economy. State-owned enterprises are still responsible for around a third of output, and exercise control over much of the strategic infrastructure, as well as playing an important role in external markets and in projects linked to the “Belt and Road” initiative.44 Cooperation with the state, at least at local level, is often an important element in ensuring the success of businesses or to access credit, still channelled to a large extent through state-controlled banks and financial institutions.45

This distinctive combination of state and capital imposes a pressure on other states. Just as China has been forced to partially reorient its economy to market imperatives, so, too, are other ruling classes reorienting themselves to meet the challenge presented by Chinese growth, giving a greater role to their own state in directing and organising capital. Biden made this explicit in his discussions of his $1.2 trillion infrastructure plan: “We’re in a race with China and the rest of the world for the 21st century… This agreement signals to the world that we can function, deliver and do significant things”.46

To a far greater extent than Trump, Biden also hopes to corral his allies into participating in this rivalry. At the recent G7 summit, held in Britain, and in subsequent meetings with NATO members and EU leaders, Biden sought to secure European backing for his efforts to contain China. As the Financial Times reported: “Biden’s…overriding preoccupation is China…the China challenge appeared three times in the G7 communiqué and was for the first time cited by NATO—an alliance supposedly about defending the North Atlantic”.47 The G7 launched a “Build Back Better World” initiative to plug a “$40+ trillion infrastructure need in the developing world”, a plan seen as a rival to China’s “Belt and Road” initiative.48 Some European leaders have themselves adopted a sterner stance towards China in recent months. Britain, France and Germany have agreed to send naval vessels to patrol the South China Sea alongside the US, and a proposed EU-China investment treaty has been put on ice. However, China remains a more important trade partner for the EU than the US, and there remains reluctance among some to accept a “binary choice” between the two major powers.49

In the context of these growing inter-imperialist tensions, the tech sector plays a disproportionate role. This reflects both the expanded role of tech giants, including the so-called “FAANGs” (Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix and Google), in the contemporary global economy and their importance to the security establishment. The furore over Chinese firm Huawei’s role in plans for the 5G telecoms infrastructure in various European countries reflects these tensions. One interpretation of Biden’s plan for a uniform minimum tax rate, however effective it proves to be, is that it seeks to anchor these firms, in particular, more tightly to the US state.50 There are also efforts by the Chinese state to tighten the regulation of its own tech giants.51

Reconfigurations 2: crisis management

There is a second major source for the reconfiguration of capitalism, again one with roots pre-dating the Biden administration, namely the efforts to navigate the crises of capitalism.

As I have argued previously in this journal, the crisis of profitability that emerged in the 1970s with the end of the long boom has never been fully resolved. By then, rather than letting crisis fully take hold, the temptation of those running states was to mobilise their now huge resources to reduce the impact of crises and rescue firms. The largest of these corporations had, by this time, reached a scale where their failure risked doing major systemic damage. Paradoxically, these efforts at crisis amelioration prevented a clearing out of unprofitable firms that could have created the conditions for a sustained boom. The result was, instead, relatively weak growth, increasingly sustained—but also made fragile—by credit expansion and asset price bubbles.52

Each crisis was met with new interventions, either directly by states or the central banks linked to them. When the “dot-com” bubble, based on the inflated stock market valuation of a previous generation of tech firms, burst in the US in 2001, the Federal Reserve stepped in to slash interest rates. This in turn helped promote a housing and mortgage bubble, which faltered in 2007, helping to trigger the 2008-9 recession. The new recession was met with bailouts and stimulus packages by states on a scale unprecedented outside of wartime. Interest rates were reduced until they were close to zero across much of the system and quantitative easing programmes were launched by central banks to inject liquidity into the system.

The severity of the downturn in 2020 that accompanied the Covid-19 pandemic reflects the failure of such measures to lift the global economy from its weak and fragile state. The 2020 crisis saw levels of intervention from the state-central bank complex exceeding those of 2008-9.53 That this could happen with relatively little dissent within the ruling class speaks to the extent to which these methods of crisis management have been normalised. Even before Biden’s inauguration, Trump had authorised “$3.5 trillion of additional pandemic expenditure”.54

There are limits to the state’s largesse. The fears of inflation that have circulated in the financial press in recent months are overstated, partially reflecting short-term bottlenecks in supply and disruption to labour markets under the pandemic. However, if the money artificially created by central banks were to be used on a large scale to fund state investment projects, an arrangement known as “monetary financing”, it is possible that this could change. Even without this, if states, particularly the weaker ones, run up too large a level of debt, bond markets may react by pushing up their borrowing costs, as happened in the Eurozone crisis in the early 2010s. In addition, some economists are now recognising that, by continuing to support cheap credit, our rulers are allowing a proliferation of zombie firms, which simply recycle their debts without engaging in large scale investment, as well as creating ever-more bloated and unstable financial markets.55 For now, however, high levels of state expenditure are the order of the day. This does not mean that the underlying crisis tendencies of capitalism are annulled, but crisis is being deferred and modified in form, even as the tensions and contradictions inherent in capitalism accumulate below the surface.

Biden is proposing to use state expenditure beyond simply the goal of short-term crisis management, whether that is dealing with recessions or the immediate health emergency caused by Covid-19. He also wants to respond to some of the longer-term structural problems in the US. This includes an open acknowledgement of the way that inequality and oppression have destabilised US capitalism. Action over inequality would also conform to the desires of large sections of the US population, a majority of whom want increased taxes on the wealthy, an expansion of welfare protections and more public housing.56

However, lest we get too carried away, Watkins points out that the cheques sent to households as part of Biden’s American Rescue Plan, which will increase the income of the poorest 60 percent by over a tenth, are nonetheless “dwarfed by the $4 trillion that accrued to the top 1 percent in 2020”. They represent a “pop-up safety net”, while leaving the “systemic reproduction of inequality unchanged”.57 These measures, together with planned “federal investment in poor black and brown neighbourhoods”, are a gauge of the reconfiguration of capitalism in this period, but we should remember that amid these changes “the ratio of capital-labour spending is still heavily tilted towards big business”.58

Meanwhile the threat from the right within US politics, one of the factors motivating Biden’s active use of the state, has not gone away.59 Trump continues to dominate the politics of the US right. Republicans are jostling to win his endorsement ahead of next year’s mid-term elections in which the party will seek to take control of both chambers of Congress, considerably weakening Biden’s ability to pass legislation.60 The limits to what Biden proposes and to what he can achieve, along with the continued menace of radical right forces, necessitates efforts by the left to organise outside the framework of the Democrats. This means drawing on and nurturing the vitality of movements such as Black Lives Matter and the sparks of workplace organisation and struggle seen in the US in recent years.61

Consequences

The growing discussion about the reconfiguration of capitalism has consequences, not just for the ruling class and for commentators on economic or political matters, but also for socialists. Most obviously, and in contrast to neoliberalism in its 1980s heyday, which sought to “depoliticise the economy, subjecting to the apparently ‘natural’ rhythms of the market”, the economy today is being re-politicised.62 If states can buck the market in the interest of preserving capitalism or strengthening US imperialism, why should the exploited and oppressed be left to the tender mercies of market logic?

This re-politicisation of the economy can strengthen illusions in the old reformist approach of seeking to capture the state to use it as a vehicle to improve conditions from above. However, where positive change does not come about, or is too modest or too slow, it can also call into question the ability of reformist forces to deliver the real changes that people need, opening the door to more radical arguments. More important still, it can create the conditions in which workers begin to demand and fight for more thoroughgoing change than that offered by the likes of Biden.

If that starts to happen, it would greatly enlarge the potential audience for revolutionary socialists. As the Polish-German Marxist Rosa Luxemburg pointed out over a century ago, the dividing line between reformists and revolutionaries is not that one group fights for reforms while the other only fights for revolution.63 Revolutionaries also engage in the struggle to wrest what we can from those presiding over the system. However, we press for reforms not through any illusions in the capacity of the capitalist state to overcome the logic of the system. We do so in order to increase the confidence, militancy and organisation of the working class in order, ultimately, to confront capitalism and the state that is an intrinsic element of that system.

Joseph Choonara is the editor of International Socialism. He is the author of A Reader’s Guide to Marx’s Capital (Bookmarks, 2017) and Unravelling Capitalism: A Guide to Marxist Political Economy (2nd edition: Bookmarks, 2017).

Notes

1 Thanks to Alex Callinicos for valuable comments on an earlier draft. “Vast impersonal forces” was the poet T S Eliot’s characterisation of the concepts needed to make sense of modern political life—see Eliot, 1960, pp163-165. It appears in an essay on culture that is surprisingly complimentary about Leon Trotsky’s Literature and Revolution, whose republication Eliot urges.

2 Luce, 2021a.

3 Freedland, 2021.

4 Barrón-López and Korecki, 2021; CNN, 2021.

5 “Reconciliation” is not used here in the political but the accounting sense. It refers to changes in taxation and spending to reconcile the budget. This approach to legislation has been taken by recent US administrations because such bills can be passed by simple majority, without requiring 60 of 100 senators to approve them.

6 BBC, 2021.

7 Politi, 2021.

8 Weisman, 2021.

9 Savage, 2021.

10 Overall “net social expenditure” in the US is second only to France in the OECD but a huge amount is composed of mandatory private expenditure (such as mandatory healthcare schemes) or voluntary private expenditure. Watkins, 2021, pp15-16, makes a similar point.

11 While the clamour for a Green New Deal has forced environmental issues higher on the political agenda, many of the key advocates of such a programme allowed themselves to be co-opted by the Biden campaign once Sanders’ bid for the Democratic nomination failed. Biden’s own proposals fall well short of what is required to meet the challenges of averting catastrophic climate change—Huber, 2021; McNally, 2021.

12 Waters and others, 2021.

13 Lenin, 1992, p8.

14 Harman, 1992; Callinicos, 2009, pp103-136; and Davidson, 2012, discuss these historical processes in detail.

15 Harman, 1991, p13.

16 Harman, 1991; Callinicos, 2009, pp83-86.

17 Cliff, 1996.

18 Harman, 2010.

19 Cliff, 1996, p171.

20 On Kidron’s contribution, see my article in this issue of International Socialism.

21 Barker, 1991, p204.

22 Callinicos, 2007, p541.

23 For an account of sub-imperialist rivalry, see Alexander, 2018.

24 Guerin, 1973, pp208-252; Paxton, 2005, pp145-147.

25 Harman, 1999, p69.

26 Harman, 1999, p75.

27 Harman, 2009, pp195-201.

28 Harman, 2009, pp202-211; Harman, 1999, pp92-93.

29 Callinicos, 2012; Watkins, 2021.

30 Harman, 2009, pp217-224.

31 Watkins, 2021, pp7, 9.

32 On orthodox Trotskyism, see, for instance, Hallas, 1971.

33 See Barker, 1979.

34 Harvey, 2003, pp141, 149, 158.

35 See Ashman and Callinicos, 2006, for a critique of Harvey’s theory of “accumulation by dispossession”.

36 SIPRI military expenditure database.

37 See Harvey, 2003, pp18-25; Callinicos, 2009, p224.

38 Anderson and Cha, 2017.

39 See Budd, 2021, for an overview of US-China relations.

40 Williams, 2021.

41 Mazzucato, 2014.

42 Atlantic Council, 2021.

43 For a fascinating new account of debates within China on market reform, see Weber, 2021.

44 See Budd, 2021, on the rhetoric and reality of this project.

45 Zheng and Huang, 2018, and Cheong and Li, 2019, are two recent attempts to describe the resulting complex mixture of state capitalism and market-based capitalism.

46 BBC, 2021.

47 Luce, 2021b.

48 The White House, 2021.

49 Sevastopulo and Fleming, 2021.

50 The G7 plan is, in reality, a narrowing of existing proposals emerging from the OECD, reducing the number of multinational affected to just 100 firms, rather than the thousands initially envisaged—Cobham, 2021.

51 Yang, 2021.

52 See Choonara, 2018.

53 Choonara, 2021.

54 Watkins, 2021, p12. Similarly in Britain, as I noted in an earlier issue, state intervention is providing huge levels of artificial support to labour markets through the furlough scheme. This is reflected in the plummeting figures for weekly hours worked, even though “official” unemployment remains quite low—see Choonara, 2021, figure 4.

55 Roberts, 2021. Astonishingly the insolvency rate in England and Wales fell in the current crisis, according to data from the UK Insolvency Service.

56 Devlin, Schumacher and Moncus, 2021.

57 Watkins, 2021, p16.

58 Watkins, 2021, p17.

59 See Callinicos, 2021a, on the contours of radical right politics today.

60 Fedor, 2021.

61 See Delatolas and Lemlich, 2021.

62 Callinicos, 2021b.

63 Luxemburg, 1971, p52.

References