Production is the essential condition for any functioning human society, and collective human labour the foundation of production.1 These basic facts are typically buried under an overgrowth of ideology but the Covid-19 pandemic has helped to strip this back, placing work at the centre of contemporary debates.

Conditions within the labour force that once passed unnoticed have suddenly emerged into the light. Addressing the shortage of hauliers in Britain, the Financial Times asked why any young person might wish to work in an industry based around 13 hour days of driving, punctuated by mandatory breaks in inadequate rest stop facilities.2 Time magazine reported a purported “great resignation” in the United States, as over four million workers quit their jobs in a single month in autumn 2021. Robert Reich, Bill Clinton’s former Labour Secretary, suggested that employees “don’t want to return to backbreaking or boring, low-wage, shit jobs. Workers are burnt out. They’re fed up. They’re fried. In the wake of so much hardship and illness and death during the past year, they’re not going to take it any more”.3

This analysis offers an account of some of the changes to work as the pandemic reaches its two-year mark. It comes with two important caveats. First, this account focuses on Britain and other similar economies. The important topic of work across the Global South is one that will be addressed in future issues. Suffice it to say here, even in countries where the direct health impact of Covid-19 has been more limited due to, for instance, relatively youthful populations, workers have not been spared more than their share of suffering. Economic dislocation in export industries and global supply chains, and declines in areas such as tourism, along with border closures and other restrictions imposed due to the pandemic, have helped drive the first global rise in extreme poverty since 1997.4

The second caveat is that the potential impact of the new omicron variant of Covid-19 remained unclear at the time of writing. The failure of governments to control the spread of coronavirus has transformed populations into petri dishes for the creation of new viral strains—a situation exacerbated by the vaccine imperialism of the most powerful states. If new strains such as omicron turn out to be more transmissible, or to have greater capacity to evade existing vaccines, then the already weakening economic recovery could grind to a halt. As International Socialism went to press, Boris Johnson’s increasingly crisis-stricken government had just announced new advice for workers to work from home where possible.5 However, it remained unclear how serious and prolonged a shift this would entail.

A peculiar kind of crisis

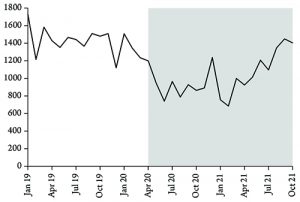

We should note, first of all, the peculiarity of the economic crisis accompanying the pandemic. As the first lockdown was imposed, Britain suffered its worst recession in over three centuries. We might envisage two likely outcomes of such a crisis: the failure of large numbers of firms and surging unemployment. The reality has been quite different. The pattern, deepening with each crisis of the 21st century and reaching new levels by 2020-1, has been intensifying action by states and their associated central banks to support firms, whether through direct interventions or measures such as ultra-low interest rates.6 This creates a situation in which unprofitable “zombie firms” survive well beyond their natural lifespan. As the pandemic erupted, firm failures fell, only returning to something close to pre-pandemic levels by autumn 2021 (figure 1).

Figure 1: Insolvencies in England and Wales before and during the pandemic

Source: Insolvency Service data.

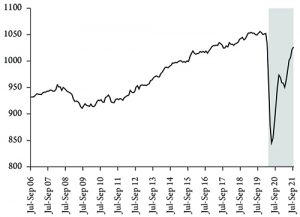

Not only that, but the furlough scheme implemented by the British state meant a far more muted rise in official unemployment rates than in earlier crises (figure 2). As with similar schemes in France, Germany, Italy and Spain, the British state found itself supporting the income of roughly a third of the workforce, with 11.7 million jobs furloughed at some point in the pandemic. Across “high-income countries”, employment fell by 18 million between 2019 and 2020, but hours worked fell by the equivalent of 39 million full-time jobs, reflecting the extent to which furlough schemes cushioned labour markets.7 A similar collapse in working hours took place in Britain, with this figure still well below levels expected from pre-crisis trends (figure 3).

Figure 2: Unemployment rate (16-65, seasonally adjusted) before and during the pandemic

Source: Office for National Statistics data.

Figure 3: Total weekly hours worked (millions) before and during the pandemic

Source: Office for National Statistics data.

In Britain, repeated extensions to the furlough scheme, paid for by expanding state debt, prevented mass unemployment. These measures, along with the vaccine rollout, helps explain Johnson’s relative success in riding out the early phases of the pandemic. A cumulative £70 billion (about 2.5 percent of annual GDP) was handed over to 1.3 million employers as part of this scheme.8

Working through the pandemic

This kind of intervention meant that the bulk of the labour force in countries such as Britain was divided into four sections—with workers sometimes moving between groups in the course of the pandemic. First, as noted above, there were those who were placed on temporary furlough. Second, there were those who left the workforce, discussed in more detail below. The third and fourth groups both consisted of people who continued working through the pandemic: respectively, those continuing to travel to their workplace and those for whom some or all their work shifted into their home. Each group was impacted by the pandemic, but not in the same manner.

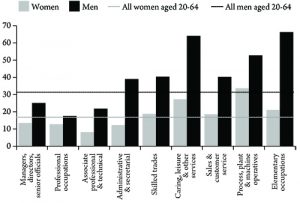

Those most at risk of death were concentrated in occupations where contact with other workers or the public was expected. As figure 4 shows, workers in “caring, leisure and other service occupations”, along with those in occupations related to manufacturing, were far more likely to die from causes linked to Covid-19. Factors such as race and class—which push people into such jobs as well as into overcrowded housing and which lead to poorer overall health—are central to explaining how excess mortality has been distributed across the population.

Figure 4: Deaths involving Covid-19 per 100,000 people between 9 March and 28 December 2020

Source: Office for National Statistics data.

There were lower levels of excess mortality in occupations with less contact with others, particularly where this work was done at home. The extent to which homeworking was used in the pandemic was unprecedented. Numbers travelling to work at least some of the time fell to their lowest ever level, about a third of the workforce, in April 2020. However, by late November 2021, around 71 percent were travelling to work. Most workers were, once more, expected to be present in the workplace.9

For those whose work could be carried out remotely, the speed of the transfer of work into the home was striking. Prior to the pandemic just 4.7 percent of employees engaged in home-working: “It had taken almost 40 years for home-working to grow by three percentage points, but its prevalence grew eight-fold virtually overnight as people were instructed to work at home if they can because of the pandemic”.10 Around a third of the workforce across Europe and in the US worked from home in early 2020. In some cases, managers had little choice but to make this shift in spite of a negative impact on productivity; in other cases, productivity rose. Overall the changes seem to have averaged out, leading to a broad continuity in the amount of work squeezed out of workers during home-working. This does not take into account other advantages for employers, in particular the potential savings from making employees responsible for supplying office space, equipment and utilities (heating, lighting, internet access) required to do their jobs.

The impact on workers’ conditions has, unsurprisingly, also been mixed. About half of those who worked at home during the pandemic reported that they would prefer to work mostly or exclusively at home in future. However, this should not be taken as a broad endorsement by workers of the experience. For many, particularly those with caring responsibilities, who are disproportionately women, working from home allows familial and work commitments to be better juggled. Were better public provision made for childcare or if more flexible working patterns were available, this preference could change. Moreover, not all workers can afford the equipment required to work safely and efficiently at home or find the space to do so. Many workers also report feeling drained and isolated or working longer hours than before.11 The workplace is a site of exploitation, bullying and oppression, but it is also a concentration of collective labour, which makes it a key arena for socialisation and allows workers to express their power. By analogy, the drawing of women out of domestic activities and into waged labour has historically been regarded by Marxists not simply as exposing them to capitalist exploitation, but also as placing them in a world in which their capacity for collective action is enhanced. Although many workers appreciate the flexibility of being able to work from home, a wholesale return of a section of the working class to a more isolated domestic sphere, without freeing them from exploitation, is hardly a panacea.

It is not simply the antipathy of workers towards working in their own homes that is likely to limit the use of remote working post-pandemic. Large amounts of employment continues to rely on access to equipment concentrated in workplaces (most obviously in manufacturing) or the provision of services that require the worker to be present alongside the recipient of those services (for instance, care work, cafes and transportation). Moreover, employers fear that managers may lose their ability to “exert direct control over and to supervise remote workers”.12 Even in areas such as finance and business services, an emerging norm at larger firms is for employees to be in the office at least two to four days a week. In cases where there is a shift towards home-working, workers and trade unions will have to formulate new demands to prevent workers subsidising their employers’ overheads or suffering extended working hours.13 However, as many areas revert to pre-pandemic patterns, workers will also have to raise demands for flexibility, though on their own terms rather than those of their employers.

Regardless of the eventual redistribution of work between the home and the traditional workplace, the deployment of digital technologies during the pandemic to facilitate the shift reminds us that the use of technology is far from neutral. Such technology does not simply permit changes to the location of work; it is also about measuring and enforcing its intensity and duration. This is a key issue in another form of work much in the spotlight during the pandemic, so-called “platform work”, mediated by online platforms. Deliveroo and Uber are the most high profile, but this type of work can also include running errands and doing housework along with a large and amorphous category of creative or technical “digital tasks”.14 As demand for such services has grown, so has the number of platform workers. One study suggests a modest growth of those obtaining more than half their income from platform work, from roughly 4.1 percent of the workforce in 2019 to around 4.4 percent in 2021.15

Although there is little evidence that platform work will displace other forms of employment, we should be aware of the parallels between the use of technology to monitor and enforce work rates in platform work and in non-platform work, particularly in the home. An estimated 9.4 percent of non-platform workers used a specifically designed platform in 2021 to receive notification of the availability of work, with 18.7 percent using a platform to log when work was done.16

A “great resignation”?

As noted, there is widespread discussion of a “great resignation”, focused on the US. Unfortunately, the reality is very far from Reich’s hyperbolic claim that “workers have declared a national general strike until they get better pay and improved working conditions”.17

In moments of economic distress, the number voluntarily leaving their jobs tends to fall, as workers seek to hold on to the work they have, while the number involuntarily leaving grows as firms close down or sack workers. These trends were reflected in the US as the pandemic began. Overall job separations rose between 2019 and 2020, driven by employers sacking workers, but the number of voluntary quits fell by 14 percent.18 The big spike in people voluntarily leaving came in autumn 2021, when the “quit rate” reached 3 percent in September, the highest figure since collection of this data began in 2000. There were rises in sectors such as manufacturing and “education and health services”. The most dramatic rise, though, was in “leisure and hospitality”, in which 6.4 percent of the workforce quit their job. However, we should not overstate the shift. Many of those quitting were people who held back from doing so earlier in the pandemic but felt able to switch jobs as recovery developed. In other words there was a backlog of people who might ordinarily have quit. The total number quitting between March 2020, when the pandemic began to hit, and September 2021, at the height of the “great resignation”, was 63,873,000. This is slightly lower than the number who quit between March 2018 and September 2019, which stood at 65,856,000.19

There has been a small decline in the US labour participation rate, but the most significant reason for this is not younger people dropping out but older people retiring: “As of August 2021, there were slightly over 2.4 million excess retirements due to Covid-19—more than half of the 4.2 million people who left the labour force from the beginning of the pandemic to the second quarter of 2021”.20 Some of this involved people bringing forward their retirement in fear of contracting Covid-19, but it also reflects the asset prices boom during the recession, due to factors such as quantitative easing, which makes retirement more attractive for some.

Similar patterns hold in Britain. There was a spike in people resigning from their job in autumn 2021, but many simply moved to another similar job. Some 57 percent of those moving jobs remained in the same industry, an increase compared to immediately before the pandemic.21 The most common reasons for leaving the labour force altogether were “long-term illness or retirement”.22

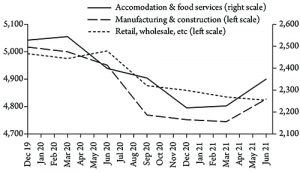

By autumn 2021, there were record levels of job vacancies, concentrated in areas such as “accommodation and food services”, manufacturing and construction. However, this sat alongside an overall drop in demand for labour compared to the immediate pre-pandemic period (figure 5). In other words, what is happening here is part of a process of economic rebound from the disruption of the pandemic. “Accommodation and food services”, in particular, is a highly casualised sector that was largely shut down for long periods in Britain. Even though many of the workers in this sector were furloughed, this does not mean that they returned to the same job when furlough ended.23 Hence the surge in vacancies now.

Figure 5: Total jobs (1,000s), selected industries, seasonally adjusted

Source: Workforce jobs by industry data, Office for National Statistics

If recovery continues, the whip of economic necessity will likely force workers who have dropped out of the workplace, particularly younger ones, to return.24 The fact that this adjustment can be prolonged and disruptive demonstrates a point that Marxists have frequently made: labour markets are complex and often recalcitrant institutions.25 The neoclassical fantasy in which supply and demand neatly adjust to smooth out the requirements of capital is just that—a fantasy. However, a long-term shift in the position of labour is unlikely without a higher degree of struggle by workers. Market mechanisms cannot substitute for this.

The cost of living crisis

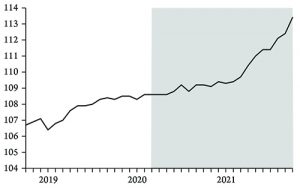

The ability of some groups of employees to leverage higher wages in the immediate future is unlikely to counteract the other issue facing workers during the recovery from the recession—the surging cost of living (figure 6).

Figure 6: Consumer price index before and during the pandemic

Source: Monthly Wages and Salaries Survey data from the Office for National Statistics.

Mainstream debate on inflation has polarised between “team transitory”, who think the inflation is a short-term response to the pandemic, and “team permanent”, who think that inflation is now more deeply embedded and here for the long term. The debate can run and run, because, as London School of Economics professor Charles Goodhart points out: “We have no general theory of inflation.” Two established mainstream theories—the monetarist theory that inflation is a result of too much money chasing too few goods and the Phillips Curve theory that predicts a trade off between inflation and employment—are both discredited.26

Even within Marxist political economy, more work is required to develop a compelling theory of inflation.27 This is not the place to attempt to provide such a theory. However, broadly speaking, inflation depends on the interrelation between value creation through the expenditure of labour power, the creation of money (primarily through the credit system), and the relationship between capital accumulation and profit rates. Vast amounts of money have been created through quantitative easing since the 2008 recession, and this certainly drove asset price inflation in the financial sector, but we did not witness a surge in the cost of living like the present one. However, if money is injected into the expansion of production but the value of the goods produced and sold is insufficient to mop up all this new money, it is possible for inflation to arise, either through firms raising prices to prop up faltering profitability or as banks continually refinance to allow them to continue their activities through monetary creation. As Anwar Shaikh points out, this is more likely to lead to inflation when the rate of profit is declining but the rate of accumulation has not fallen accordingly, thus sustaining overall demand levels.28

However, the pattern in countries such as the US and Britain since the 1990s has tended to be for the rate of accumulation to decline in line with profit rates.29 Of course, if states embark on a massive programme of investment financed by money created by central banks, there is always the potential for inflation, but so far there is little evidence that this occurring on a sufficient scale. The rise in inflation we are seeing today is more likely a result of the restoration of previous levels of demand in conditions of dislocation and disruption to supply chains and labour markets generated by the pandemic.30 This has been exacerbated by a lack of investment in oil and gas production, combined with geopolitical tensions, which has pushed up energy prices as demand has rebounded.

If this is correct, inflation is likely to return to lower levels. Indeed, the greater danger may be an overreaction by central banks, in which a rise in interest rates chokes off the delicate recovery altogether.

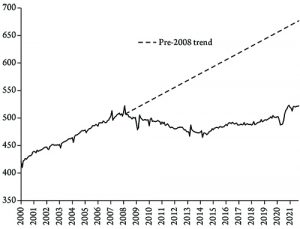

However, saying that inflation will probably ebb is hardly reassuring to workers. “Short term”, in this context, can mean months of pain. Workers have to eat and heat their homes now, not in some hypothetical future. Moreover, the rise in the cost of living comes after a decade of stagnating real wages (figure 7). It is absolutely right for workers to demand a pay rise. There have been some important strikes in recent months—notably those by university staff—and a smattering of victories, particular by workers in transport and logistics, either through threatening or taking industrial action. The recently elected leader of the Unite union, Sharon Graham, is quite right to point out that anything below a 6 percent pay rise is a pay cut.31 However, much more could be done by the trade union leaders to translate growing discontent among workers into action. In the absence of this, or any lead from the still rightward moving Labour Party leadership of Keir Starmer, socialists will have to do what they can to channel the anger of workers into sustained and collective struggle.

Figure 7: Real Average Weekly Earnings (2015 £s)

Source: Office for National Statistics data.

Joseph Choonara is the editor of International Socialism. He is the author of A Reader’s Guide to Marx’s Capital (Bookmarks, 2017) and Unravelling Capitalism: A Guide to Marxist Political Economy (2nd edition: Bookmarks, 2017).

Notes

1 Thanks to Richard Donnelly and Mark Thomas for feedback on an earlier draft of this article.

2 Thomas, 2021.

3 Vesoulis, 2021.

4 See Appiah, 2021.

5 There was widespread speculation that the announcement was timed to distract from the denunciation of Johnson for permitting Christmas parties in Downing Street at the height of the lockdown in winter 2020.

6 See Choonara, 2018 and 2021.

7 International Labour Organization, 2021, p22.

8 See Office for National Statistics documents from 4 November 2021—www.gov.uk/government/statistics/coronavirus-job-retention-scheme-statistics-4-november-2021

9 There was considerable unevenness here. One in five workers in London said it was impossible to work from home, half the rate reported for the north of England. Younger workers were also less likely to be able to work from home, probably reflecting their concentration in the service sector. See the 3 December 2021 edition of the “Opinions and Lifestyle Survey” published by the Office for National Statistics.

10 Felstead and Reuschke, 2021.

11 Felstead and Reuschke, 2021.

12 Hurley, Fana and others, 2021, p59.

13 For instance, the Unite union has produced a template home-working framework agreement—https://bit.ly/3lVX3kT

14 Spencer and Huws, 2021.

15 Spencer and Huws, 2021. A larger pool of about 14.7 percent do some such work on a weekly basis but it was less critical to their income. How persistent this trend will be remains to be seen.

16 Spencer and Huws, 2021.

17 Reich, 2021.

18 “Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey” data from the Bureau for Labor Statistics.

19 Bureau for Labor Statistics data. Seasonally adjusted for total non-farm employment.

20 Castro, 2021.

21 Swindells, 2021.

22 Financial Times editorial board, 2021.

23 About 3 percent of furloughed employees were made redundant, with a similar number choosing to leave, and 16 percent being offered reduced hours. See the “Business Insights and Conditions Survey” (4 November 2021) from the Office for National Statistics.

24 Much of the wage growth seen in recent months is a result of workers returning to employment from furlough or seeing their hours increase, as well as compositional effects such as those on lower wages being more likely to lose their jobs or be furloughed—Athow, 2021.

25 Choonara, 2022; Doogan, 2009.

26 Weldon, 2021.

27 For a selection of views, see Shaikh, 1999; Saad-Filho, 2000; Roberts, 2020.

28 Shaikh, 1999.

29 See, for instance, Williams and Kliman, 2014.

30 Rees and Rungcharoenkitkul, 2021.

References