And when war is waged between two groups of predators and oppressors merely for division of the spoils of plunder, merely to see who will strangle more peoples, who will grab more, the question as to who began this war, who was the first to declare it and so forth, is of no economic or political significance.

Lenin: “In the Footsteps of Russkaya Volya”, 13 April 1917.1

In every country preference should be given to the struggle against the chauvinism of the particular country, to awakening of hatred of one’s own government, to appeals…to the solidarity of the workers of the warring countries, to their joint civil war against the bourgeoisie. No one will venture to guarantee when and to what extent this preaching will be “justified” in practice: that is not the point… The point is to work on those lines. Only that work is socialist, not chauvinist. And it alone will bear socialist fruit, revolutionary fruit.

Lenin: “Letter to A G Shlyapnikov”, 31 October 1914.2

The most powerful military alliance in the world met in Newport, Wales, at the beginning of September. It was, arguably, the most significant meeting of the NATO alliance since the fall of the Berlin Wall. Two issues dominated the NATO agenda: the rise of Islamic State and, beyond all expectations, the apparent success of Vladimir Putin’s strategy in Ukraine.

Armed conflict has raged over eastern Ukraine for five months. Over 3,000 have been killed and more than 6,000 injured. The United Nations Refugee Agency estimates over a million people have been displaced, 94 percent of them residents of Ukraine’s two eastern regions. Some 15 percent of the local population have fled their homes, either to Russia or elsewhere in Ukraine. Intensive shelling of residential areas has inflicted major damage, and many who remain have little access to food, water or electricity.3

A few weeks before the NATO summit the separatists of eastern Ukraine had appeared on the verge of defeat and Putin faced humiliation in Russia’s “near abroad”. Yet in mid-August the separatists successfully mounted a counter-offensive, equipped with Russian weaponry and supplies and supported by significant numbers of Russian troops (or “volunteers”). The Ukrainian government claimed that Russians spearheaded the attack and that it was they who turned the tables, not the separatists. Whatever the precise combination of forces, the Ukrainian army and its militias were thrown into retreat. Newly elected Ukrainian president Petro Poroshenko agreed a ceasefire on 5 September. Vladimir Putin has reminded the West that, though weakened, Russia is still an imperialist power to be reckoned with, especially in its own backyard.

It is not over. Whether or not the fighting resumes in the country itself, a “frozen conflict” in Ukraine has huge implications for Russia’s entire southern flank from the Baltic states to Central Asia. Renewed tensions are mounting between Armenia and Azerbaijan and between the central Asian states. Russia and the West have their own stake in each and Georgia and Moldova also remain potential flashpoints.

In the wake of the Ukraine crisis NATO is establishing a “rapid reaction force” in the Baltic states and Eastern Europe; United States president Barack Obama has insisted NATO is open to new members on Russia’s borders, however unlikely that may now seem. The Baltic states and Poland have demanded permanent NATO bases as opposed to the current temporary ones. Russia for its part has announced large-scale strategic nuclear missile exercises this September and Putin has reminded the West that “Russia is one of the most powerful nuclear nations. This is a reality, not just words”.4 As winter approaches, both Europe and Russia face continuing economic crisis and the prospect of a sanctions and energy supply war.

This does not mean Armageddon is round the corner. The West and Russia both face real limits on their ability to manoeuvre, and their current strategy is premised on avoiding direct military conflict. The establishment of permanent bases in the Baltic republics and Poland is still not certain. NATO leaders made it clear to Poroshenko that they would not supply Ukraine with the military hardware needed to roll back the counter-offensive, precisely for fear this could lead to a full-scale invasion by Russia and threaten a wider conflict. It was this that forced an ashen-faced, humiliated Poroshenko to agree to a ceasefire.

Russia for its part has no wish to get bogged down in eastern Ukraine as a permanent occupying military force. So Putin has exerted authority over his own proxies, finally moving against the mainly Russian leadership of the separatists, who had provided cover for arms-length Russian intervention in Crimea and eastern Ukraine, but whose fantasies of restoring the Russian empire made them strategically unreliable at the endgame. Paradoxically, it was only once they were replaced with a leadership more compliant to Moscow that Putin committed the logistical support and the detachments of Russian troops needed to turn the tide, confident that he could control the outcome and impose a ceasefire broadly on his terms.

A quarter century after the end of the Cold War, Russia and the West are facing each other down across Ukraine. Despite their wish to avoid direct military conflict or wider regional instability, we should remember, a century after the First World War, that military and economic rivalry have a habit of escaping beyond the intentions and best laid plans of the contenders. After all, the current crisis took Ukraine, Russia, the European Union (EU) and the United States all by surprise and unprepared.

While it would be a mistake to conclude that we are on the brink of a European war, this is not a conflict that will simply blow over. We are at a turning point; the rivalry over Ukraine poses real dangers and presents a serious challenge to the left and to the anti-war movement.

In his 1999 book, Ukraine and Russia: A Fraternal Rivalry, Anatol Lieven wrote that he was generally optimistic about Ukraine as long as three conditions were met:

- That the Ukrainian state was not perceived by Russian speakers and ethnic Russians as having caused a breakdown with Russia.

- That Russia did not attempt to spread an ethnic chauvinist version of Russian nationalism beyond its borders.

- That the West did not pursue a “balance of power” strategy leading to confrontation.5

All these three conditions lie in shreds. Lieven, it has to be said, believed then if not now, in the possibility of a benign Western foreign policy and, for that matter, a benign Russian one too. However, a Marxist analysis cannot start from wishful thinking. We have first to situate national conflicts in the context of dynamics of global and regional power. We live in an imperialist world system, a system of competing capitals and competing capitalist states. This was the starting point for Lenin and his fellow revolutionaries when addressing the position socialists should take towards imperialist war in 1914. It remains an indispensable starting point for socialists today.6

Second, when looking at a conflict of the kind we have witnessed in Ukraine, we must ask how the unity of workers across national and ethnic divides is to be achieved. This cannot be reduced to an abstract formula but is a question we must look at concretely.

Ukraine: A history of imperialist rivalry and slaughter

Ukraine means, in a literal sense, borderland. Throughout its history imperialist armies have marched across its territory; in the modern era the Tsars, the Poles and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. During the Russian Revolution some of the most critical battles of the civil war were played out in Ukraine between the Red and White armies, and Polish and German forces. The Bolsheviks’ attitude to the national question was put to perhaps its severest test, in circumstances where counter-revolution was organised under the banner of “an independent Ukraine”.

After a political struggle by Lenin and others, the Bolsheviks granted Ukraine’s right to self-determination. The immediate post-revolutionary period saw a flourishing of Ukrainian art and culture. But at the end of the 1920s Joseph Stalin launched his counter-revolution. In 1928 the campaign to forcibly collectivise agriculture began. Vast resources of food and land were expropriated from the peasantry, and Ukraine, the most fertile area of the Soviet Union, was plunged into a famine that left 3 million dead.

The counter-revolution swept away the entire gains of the revolution including all forms of national and language rights. The old Bolshevik leadership of Ukraine, associated with the post-revolutionary period of “Ukrainisation”, were purged. Almost the entire central committee and politburo of Ukraine and an estimated 37 percent of Communist Party members, about 170,000 people, perished.

Imperialist rivalry was also a driver of Stalin’s purges.7 The purges of the Ukrainian and Polish Communist Parties were particularly intense, even by the grotesque standards of the Great Purge. They came as Stalin contemplated his strategy for the oncoming carve-up of Europe that culminated in the Stalin-Hitler pact.8 In Vinnytsia a mass grave was unearthed by the Nazis containing the bodies of 10,000 people shot between 1937 and 1938. The massacre could not be referred to officially in the Soviet Union and was not acknowledged until 1988.

During the Second World War an estimated 7 million Ukrainians lost their lives, including 900,000 Jews at the hands of the Nazis. Again imperialism ripped Ukrainian society apart, setting ethnic Ukrainian against ethnic Russian, against Pole and, of course, against the Jews. The experience of Soviet occupation under the Stalin-Hitler pact and the sufferings of the Stalin period led a minority of Ukrainians to see the Nazis as “liberators”. A reactionary Ukrainian nationalist movement emerged, including many fascists, which collaborated with the Nazis and massacred Jews and Poles as well as Ukrainians.

Trotsky raged at the disastrous consequences of the carve-up and Stalin’s decimation of Ukraine:

Since the latest murderous “purge” in the Ukraine no one in the West wants to become part of the Kremlin satrapy which continues to bear the name of Soviet Ukraine. The worker and peasant masses in the Western Ukraine, in Bukovina, in the Carpatho-Ukraine are in a state of confusion: Where to turn? What to demand? This situation naturally shifts the leadership to the most reactionary Ukrainian cliques who express their “nationalism” by seeking to sell the Ukrainian people to one imperialism or another in return for a promise of fictitious independence. Upon this tragic confusion Hitler bases his policy in the Ukrainian question.9

Ukraine’s borders and its populations have been repeatedly torn asunder. Now Ukraine finds itself at the fulcrum of an arc of tension that stretches across Russia’s southern flank from the Baltics through the Caucasus to Central Asia. Sherman Garnett has termed Ukraine “The Keystone in the Arch”, referring to its critical geopolitical location between Western Europe and Russia. The orientation of Ukraine between East and West, Garnett argued, would determine the dynamic of rivalry and conflict from the Baltic Sea to Central Asia. Perceptively he warned that NATO’s expansion would lead to internal conflict if Ukraine were torn between Russia and the West. Both Garnett and Lieven argued that any attempt on the part of the West to engage in a tug of war over Ukraine could destabilise not only Ukraine but the entire region.10

Ukraine is the largest country entirely in Europe, with the second largest population. It shares borders with Hungary, Slovakia and Poland to the west; Belarus to the north; Russia to the north and east; and Romania, Moldova and its pro-Russian breakaway Transnistria to the south. As the annexation of Crimea highlighted all too clearly, Ukraine has a key strategic coastline on the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov, across which lie Turkey and the Caucasian states of Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan (all subject to their own rivalries and conflicts); beyond that lie the Caspian Sea, Central Asia and that other rising, rival imperialism, China.

Ukraine

Russian sphere: Belarus; Kazakhstan; Armenia

EU sphere: Moldova; Georgia

Between spheres: Azerbaijan; Turkmenistan; Uzbekistan

Class conflict and national divisions

The Maidan protests (which took their name after the central square in Kiev) began in autumn 2013. They were triggered by President Viktor Yanukovych’s refusal to sign an Association Agreement with the European Union (EU). The students who made up these initial protests looked to the market, Europe and the West for an alternative to the corruption of the Ukrainian elite and their smashed hopes of a post-Communist economic future.

It is important to note that this was not the first protest movement to challenge a Ukrainian regime. In 1990 a group of students also occupied the Maidan. They were inspired by two key events: first, the miners’ strikes that shook the Soviet Union in 1989, when tens of thousands of miners occupied their town squares, including in Donetsk in eastern Ukraine, banging their helmets, their eyes rimmed with black coal dust, demanding soap and democracy. Second, by the Chinese students in Tiananmen Square. They set up a tent city, began a hunger strike and demanded sovereignty for Ukraine (not independence) and democratisation. The protests became known as the “Revolution on Granite” after the granite paving of the Maidan. The protests reached hundreds of thousands, part of a wave of mass movements demanding national independence across the Soviet empire.11

By mid-October 1990, however, there was a stand-off. The government refused to negotiate and the threat of reaction loomed as the regime prepared to use force. The turning point came when a large column of workers from Kiev’s largest factory, a core part of the Soviet military-industrial complex, employing tens of thousands of workers, marched on parliament in support of the students. As Bohdan Krawchenko describes:

On 18 October, unexpectedly, a large column of workers from Kiev’s largest factory marched on parliament in support of students. They chanted only one word, their factory’s name-”Arsenal”. Workers tipped the balance. That evening the government reported that it would meet all student demands. Kiev celebrated the victory into the early hours of the morning. The students had stopped the march of reaction in its tracks.12

The struggles for independence, democracy and the strikes over economic demands across Ukraine demonstrated the potential for united resistance. The Donbass miners’ strikes were supported in the West, and joined by important mining centres in the heartlands of western Ukrainian nationalism. The referendum on independence in 1991 had a turnout of 84 percent. Even in the industrialised regions in the east such as Donetsk and Luhansk where the majority were Russian speakers and with the highest numbers of ethnic Russians, support for independence did not dip below 83 percent. The one exception was Crimea, a military bastion of Soviet imperialism, and even here 54 percent of the ballot was cast in favour of independence.

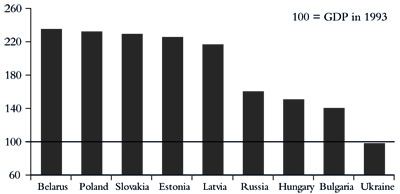

However, the post-Soviet economic collapse began to fuel divisions. The hopes of 1989-1991 were dashed on the rocks of shock therapy and hyperinflation, exceeding even the horrifying descent of the Russian economy. Annual inflation in Ukraine for the period 1993-5 averaged 2,001 percent per year (the figure for Russia for the same period was 460 percent).13 Living standards plummeted and lifetime savings and pensions evaporated; Ukraine was at the eye of the neoliberal economic storm. Today Ukraine is the only Eastern European state whose level of production stands at pre-1993 levels (see figure 1).

Figure 1: Gross Domestic Product (GDP) compared to 1993

Source: World Economic Outlook

A minimal recovery after 2000 was followed by the 2008 crisis: world steel prices fell; national debt on vast foreign loans mushroomed; reserves evaporated. The economy contracted by 15 percent and the currency lost 40 percent of its value. Per capita income (2013) and average life expectancy in Ukraine compared to its neighbours give an indication of what this means.

Income per capita (US dollar equivalent)

Source: World Bank

| Ukraine | 3,900 |

|---|---|

| Hungary | 12,560* |

| Poland | 13,432 |

| Russia | 14,612 |

*2012 data

Male life expectancy (2014 estimates)

Source: CIA World Factbook and The Lancet

| Ukraine | 63.78 (61.2 years in east Ukraine) |

|---|---|

| Hungary | 71.73 |

| Poland | 72.74 |

| Russia | 64.37 |

However, as workers in both east and west saw their futures evaporating, one group of Ukrainians did very well indeed amid the post-Soviet collapse. The oligarchs, who rose from the ranks of the old Soviet ruling class (the nomenklatura) who were joined by new rising entrepreneurs cum gangsters, acquired vast wealth in the privatisation fire sale of state assets and new business interests.

Rinat Akhmetov, for example, now the wealthiest oligarch, built his fortune in the mining and steel industries in the east. He has interests in both Russian and Western markets and, like most oligarchs, is keen to keep both Russian and Western competitors out of the sectors where he makes his profits. He is worth (advisedly) over $14 billion. He controls more than 50 percent of the country’s electricity and energy coal production, with interests in ore mining, steel, media, real estate, oil and natural gas.

There is another side to Akhmetov’s wealth. Ukraine has the highest mining death rate in the world. The death rate per million tonnes of coal dug is three times that of China, ten times that of Russia and 100 times that of the United States-all for less than £200 a month. At one of Akhmetov’s mines, the Sukhodilska-Skhidna pit, 127 miners died in a methane gas explosion in 2011. A miner, Smetanin Ihor Vladimirovich, described the conditions that caused the accident:

Yesterday I helped bring up the dead guys to the surface. I cried half a night after this. I overheard someone say there was 5 percent of methane instead of a half-percent. If there is a leak, nobody can leave. They just push in some fresh air and keep you working. Otherwise, you lose your job.

I’m paid Hr 1,30014 for a hellish job in the shaft; there is a lot of coal dust and no air circulation. In winter time, the shower has no heating… We get treated like animals…

I saw those dead guys. They had no shoes. One was missing half a head. I worked the whole day, but in the evening I collapsed and cried till three in the morning. I never cried at anyone’s funeral. I am really sorry for them as a human. Really sorry.

And they died because [they tell us] “Come on! Faster! Give us coal output. Give us a new shaft! Give us millions!”15

The obscene wealth of the oligarchs was epitomised by the family of President Yanukovych: when protesters broke into his mansion they wandered stunned at the pure copper roof, private zoo, underground shooting range, 18-hole golf course, tennis courts, bowling alley and a gold plated bidet. Among the invoices were found $30 million for chandeliers with $5 million small change spent on switches and fittings. This is in a country where 35 percent of the population live below the poverty line.

After 1991, as the crisis wrecked the lives of ordinary Ukrainians, oligarchs and politicians encouraged regional and ethnic loyalties and divisions. Even where political leaders attempted to balance rival economic and regional interests they increasingly resorted to playing the ethnic and nationalist card in order to secure a political base against their rivals and to deflect popular anger away from themselves.

The growing splits between these groups of equally corrupt politicians and oligarchs culminated in the so-called “Orange Revolution” of 2004. Although it was triggered by a rigged election, neither side cared about democracy. Western leaning politicians knew of the fraud, which was an open secret, and planned mass protests, although they were by no means confident of winning support or resisting a crackdown. However, the numbers flocking into the square far exceeded expectations and the pro-Western politicians found the lever they needed. As the crisis grew, the ruling elite in the east threatened separation but backed down. At no point did the movement break from the grip of the elite on either side.

After the crisis of 2008 elements of the ruling class employed a divide and rule strategy with a vengeance. The Russian speaker in east Ukraine was portrayed by Ukrainian nationalists as a “coloniser”, belonging to a foreign fifth column, who had conspired to destroy Ukrainian culture and language, guilty by association with the famine and the purges. The Ukrainian speakers in the west were portrayed as filthy Galician Nazi collaborators, who hated ethnic Russians and Russian speakers, and were out to suppress their language and rights. Ethnic and national divisions were deepened by the impact of crisis and the role of the elites. They are not written into Ukrainians’ historical genes but had to be forged and fostered.

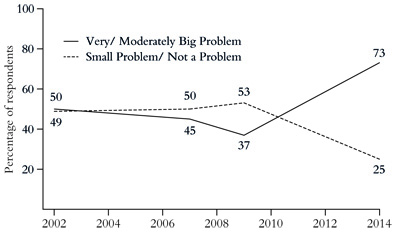

Under pro-Western president Viktor Yushchenko the government promoted an ultra-nationalistic reworking of history. The Nazi collaborators of Stepan Bandera were rehabilitated and Bandera himself was posthumously awarded the title “Hero of Ukraine” in 2010. Meanwhile the mainstream media gave increasing coverage to the Nazis of Svoboda.16 This did not help Yushchenko, however. By the end of his presidency he was totally discredited, scoring 5 percent in the 2010 presidential elections. Up until 2009 ordinary Ukrainians’ concern about ethnic conflict was declining. But, as figure 2 shows, there was a sudden upturn in the wake of the crash and the stoking of tensions by the elite.17

Figure 2: Ukrainians’ concern about ethnic conflict

Source: Pew Research Centre—Spring 2014 Global Attitudes Survey

Nonetheless, as political geographer Evan Centanni observes, the mainstream media have misrepresented the divisions in Ukraine. In response to an article by the Washington Post’s Max Fisher,18 Centanni writes, “There’s not, as Fisher preposterously claims, ‘an actual, physical line’ splitting Ukraine in half. Instead, there’s a gradual shading of mixed populations whose ethnic identities and voting history don’t always correlate to the country’s current political divisions”.19

The language question has also been subject to much misrepresentation. There was systematic suppression of the Ukrainian language under Soviet rule. By 1988 only 28 percent of all Ukrainian children were taught in Ukrainian language schools compared to 89 percent in the late 1930s.20 Yet prior to the Maidan crisis many old divisions of language and ethnicity were breaking down, especially among Ukrainian youth. Between 2003 and 2010 the percentage of young people using only Ukrainian or only Russian dropped significantly. The category that increased was the bilingual use of both the Russian and Ukrainian languages, rising from 18.9 percent in 2003 to 40.3 percent in 2010.21 The truth is that over a vast swathe of Ukraine, including the east, ethnic Ukrainians speak Russian, intermarry with ethnic Russians and they all converse in both languages at home, work and with friends and neighbours.

Similarly, the most important issues for young Ukrainians were the right to work; the right to a home; the right to education; freedom from arbitrary arrest; freedom of speech; freedom of movement and freedom of conscience respectively.

This helps explain the inability of the far-right Ukrainian nationalists to attract more than minority support, overwhelmingly confined to the far western regions of Galicia and Volhynia. Likewise the great Russian chauvinists have proved incapable of winning support beyond the two eastern regions of Donetsk and Luhansk and parts of the south. The political appeal of movements based on a narrow chauvinism is limited. Before May 2014, despite rising tensions, the majority of ethnic Russians were opposed to separation. Overall only 14 percent of Ukrainians wanted to allow regions to secede. In the eastern regions this rose to 18 percent and even among Russian speakers in eastern Ukraine only 27 percent wanted to allow secession.22

The struggles of 1989-91 and growing social integration had demonstrated the potential for unity among ordinary Ukrainians. Two factors undermined this process: first, in the face of ongoing political and economic crisis, rival sections of the ruling elite fostered regional and ethnic division; second, these rival camps were in turn pulled by both the West and Russia who each wanted to forge Ukraine as a “buffer” state against their rival.

Maidan

By the end of 2013 the Ukrainian ruling class were desperate. The central bank had two months of foreign reserves left and Ukraine was judged twice as likely to default as Greece.23 The ruling class desperately needed a bailout from either the EU and IMF or Russia. Either would come at a heavy price; both would offer nothing but continuing misery for Ukraine’s workers. After some hesitation Yanukovych turned to Russia, refusing to sign the Association Agreement that had been negotiated with the EU.

This triggered a reaction that had its roots in the shared rage at the crisis and hatred for the oligarchs common to both east and west. However, the protests could never develop into a national movement as long as their demands were hitched to the EU and the West. The seeds of division had already been sown. The nature of the demands meant that the student-led protests of early autumn were reaching a limit beyond which they were unlikely to generalise further. Arguably, by the end of November the protests were on the wane. But on 30 November Yanukovych and his supporters made a fateful decision.

In two years Yanukovych had seen his support slump from 42 to 14 percent; he feared the protest movement might just be sufficient to dislodge him. Memories of the “Orange Revolution” of 2004 and the precedent set by the “Revolution on Granite” of 1990 had more than a symbolic resonance for Ukraine’s rulers. Yanukovych decided to sweep the protesters from the square in an action that he hoped would bring the protest to a rapid end. He sent in the notorious interior ministry troops: the “Berkut” (Golden Eagles) to disband the students violently. The Berkut had their roots in the Soviet OMON formed at the end of the 1980s to take on the miners and the independence movements. They were paid double the wages of the ordinary police and had a deeply anti-Semitic culture. They went on a violent rampage not only clearing protesters from the square but pursuing them through the streets with clubs and laying siege to St Michael’s Monastery where many took sanctuary.

Demonstrations of tens of thousands were transformed into demonstrations of hundreds of thousands and more. By early December up to half a million demonstrated. The motivation of the demonstrators is instructive. In a poll conducted among 1,037 demonstrators in and around Maidan square on 7-8 December, 70 percent said they came to protest against the police brutality of 30 November; 53.5 percent in favour of the EU Association Agreement; 50 percent “to change life in Ukraine”; 40 percent “to change the power in the country”. Only 17 percent protested for fear that Ukraine would enter Russia’s Customs Union or against the possibility of a turn back towards Russia. A negligible 5.4 percent said they answered the calls of opposition leaders.24 As David Cadier observes: “The protests, while initially prompted by the rejection of the Association Agreement, grew considerably bigger and more determined after the police had repressed them; they became less about allegiance to either the EU or Russia than they were about denouncing a corrupt and inefficient political executive”.25 Once at the square the demands of the political opposition came more to the fore. But nonetheless when asked to choose which three political demands they most supported, signing the EU agreement came fourth with less than half the protesters including it as a demand. First, by a significant margin, was the release of those arrested on the Maidan and an end to repression; second, the dismissal of the government; third, the resignation of Yanukovych and early presidential elections.26

Confrontations and demonstrations continued through the winter. Then on 16 January the government passed a series of anti-protest laws, soon called “the dictatorship laws”, that included ten-year jail terms for blockading government buildings, one-year jail terms for slandering government officials or “group violations of public order”, amnesty from prosecution for the Berkut and law enforcement officials who had committed crimes against protesters, and a host of other measures. This triggered a further wave of mass protest against which the Berkut launched its most vicious and murderous onslaught. Over 100 protesters were killed. The fascists and ultra-right were able to present themselves both as victims and as the most determined defence against the Berkut and came to the fore in many of the confrontations that ensued.

The government strategy backfired disastrously. Yanukovych fled and the ruling Party of the Regions all but collapsed as the oligarchs and deputies cut loose. The beneficiaries were the pro-Western oligarchs and politicians who brought the fascists of Svoboda and the Right Sector on board, appointing them to key ministerial posts.

This process has been depicted by a section of the left as a putsch from beginning to end. This is dangerous nonsense, and at best confuses outcome with intention. It ignores the role of the Berkut and the slaughter of demonstrators in much the same way as some pro-regime supporters ignore the massacre of anti-Kiev activists in Odessa by a pro-Kiev mob and the Right Sector. But it was not Svoboda, the Right Sector or the pro-Western politicians who turned the early demonstrations into mass protests-it was the turn to deadly force by Yanukovych and his supporters, a decision that led to his downfall, leaving a vacuum that the pro-EU, pro-Western politicians stepped into.

Ukraine: between East and West

Ever since the fall of the Soviet Union, the EU and NATO have sought to expand their sphere of influence into the former Soviet bloc, while Russia has sought to retain influence and, where possible, restore its own dominance over its “near abroad”-the former republics of the Soviet Union that won independence after 1991.27

The balance has long been in the West’s favour and Russia could do little or nothing as one by one Eastern European countries, including the Baltic states, signed up to the EU and NATO. By 2009, 12 former Communist states had joined NATO, 11 of them joining the EU. In 2014 Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine all signed an EU “Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement”.

It is important to grasp that the gathering tensions over the membership of rival trade blocs in Eastern Europe and the Russian periphery are not incidental, nor simply a matter of an aggressive foreign policy on the part of the EU; neither are they simply a sentimental attachment to former empire or just fear of encirclement on the part of Russia. This is not a matter of joining a “club” in order just to get some attractive offers or deals. The rivalry over these regional economic blocs is an expression of the economic competition between capitals on a world scale.

At stake are vast resources and markets. Each bloc is compelled to seek maximum competitive advantage against its rivals and to strengthen its competitive position in the world market. The European Union was formed precisely so that its member states could compete against other major economies such as the US, Japan, the south-east Asian states and now China. With the end of the Cold War, it was inevitable the EU would turn eastwards.

David Cadier, albeit in the language of an academic economist, has quite astutely traced the dynamic of competition between the EU and the Russian sponsored Eurasian Customs Union (ECU) and the contradictory pressures this competition exerts on the states they wish to “integrate”. As in the case of Ukraine, none of these states fall neatly into one economic sphere of influence or the other. They all have conflicting interests in both Russia and its ECU partners and in EU markets28 most are also heavily dependent on Russian gas and energy supplies. The principal rivals themselves are also highly interdependent on one another.

Despite this, both “partnerships” are mutually exclusive; their rules preclude membership of both regional blocs. As Lenin and Bukharin observed a century ago in arguing against Karl Kautsky, increasing economic integration on a world scale does not reduce competition. On the contrary, the pressure to seek advantage at the expense of a rival capital, or seize the resources and markets it controls, means that competition will always reassert itself, however “illogical” this may appear.

Cadier argues that these economic “partnerships” are “two competing region-building endeavours” aimed at the same group of countries in Russia’s “near abroad”; both Russia and the EU therefore attempt to shape the economic, administrative and, to some extent, political structures of the states of their common neighbourhood, albeit by different means and with differing records of success”.29 In Marxist terms, we are back to the classic analysis of imperialism-the development of economic competition between blocs of capital-and military rivalry between states.

It is no accident that competition between the EU and Russia came to a head over Ukraine, even though neither side anticipated the outcome and both miscalculated badly. The world economic crisis of 2008-9 has led to greater pressure on the ruling classes of nation states outside the major regional trade blocs to seek “partnership” deals or membership status, whatever the costs. The impact of the crisis on trade and rising deficits increases the need to reduce tariffs (itself a tool of capitalist competition). This combined with rapidly depleting reserves puts immense pressure on these states to sign up to these “partnerships”, whatever the terms. The terms, of course, come at a price for the workers of these states themselves.

Ukraine is a classic example. President Yanukovych attempted to balance between the ECU and the EU and keep a foot in both. He sought observer status in the ECU while at the same time negotiating the Association Agreement with the EU. However, Ukraine’s looming economic crisis and the “take it or leave it” terms presented by both Russia and the EU would not permit this balancing act to continue. The EU overplayed its hand, and Yanukovych turned to Russia. The balancing act was over and Ukraine toppled.

Russia has always drawn red lines round the bordering states of Belarus, Moldova, Ukraine, Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan. However, some of these states significantly outweigh others in importance. Ukraine was the jewel in the crown. Ukraine joining the ECU was essential to Putin’s regional economic project. Without Ukraine the ECU just leaves Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan, an altogether reduced project entirely, and one that other states have less incentive to join.

The economic expansion of the EU also carries with it the threat of ever greater military encroachment by NATO. If Ukraine were to slip out of Russia’s orbit altogether, Russia’s regional and global position would be immeasurably weakened. Putin was never going to let that happen. While he had never calculated on the fall of Yanukovych and his replacement by a pro-Western regime in Kiev, the West for its part grossly underestimated Russia’s determination. When Yanukovych fell and Ukraine turned west, Russia’s economic levers were no longer sufficient and Putin deployed Russia’s geopolitical advantage and military resources to de-stabilise Ukraine and at the very least, prevent it from integrating fully into a Western economic and military alliance.

Russia’s strategy over Ukraine followed a pattern of intervention it has adopted since the 1990s. Russia has avoided becoming militarily involved in neighbouring states, with the notable exception of Chechnya, which it invaded after the republic declared independence. The war in Afghanistan and the first war in Chechnya aroused massive opposition in Russia and the legacy continues to hang over Russian foreign policy.30 Instead Russia fostered national and ethnic conflicts that destabilised neighbouring states and made them dependent on Russian goodwill.

The price of this policy was a series of bloody conflicts across Russia’s near abroad in which Russia played a key role. These included the separatist conflicts between Georgia and the breakaway regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia; Moldova and its pro-Russian breakaway Transnistria and the conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan over the enclave of Nagorno-Karabakh.31 Rather than committing large numbers of troops and armour, Russia relied on “volunteers”, often highly trained, experienced, middle-ranking military and intelligence officers, to lead and direct local forces on the ground and provide a conduit for Russian weaponry and logistical supplies. In the course of these conflicts there emerged a highly ideological layer of deeply reactionary Russian nationalists, motivated by dreams of restoring the Russian/Soviet empire.

Many of these figures gravitated around the far-right “Eurasianist” movement led by the fascist Aleksandr Dugin and the anti-Semitic newspaper Zavtra (Tomorrow) and news network Den (The Day) led by the far-right reactionary Aleksandr Prokhanov. These were part of a “red-brown” alliance of Stalinists, great Russian chauvinists and outright fascists whose leading figures were cultivated at arms length by the Kremlin.

From 2000 onwards Putin built up a far more professional, paid and better equipped military, on the back of a tide of energy wealth as the price of oil and gas on the world market rose from $30 to $130 a barrel bringing a vast flow of capital. However, these military resources have so far been used to strengthen Russia’s strategy in using proxies to destabilise its neighbours rather than supersede it.

Russia’s strategy came to a head in 2008 when Russia humiliated the West in a short, sharp five-day war to prevent Georgia from moving to join NATO. Russia used the pro-Russian enclave of South Ossetia as a mechanism for de-stabilising Georgia; Georgia then overplayed its hand thinking that it would have the backing of the West and attacked the South Ossetians. Russia responded with troops and air cover in support of the rebels. Since then Russia has continued to use its economic leverage on Georgia, not least through energy supplies.

Western imperialism and the Russian “bear”.

Those who choose to weigh one imperialism against another in favour of whichever they see as “the least bad” often justify their position by overstating the threat from Russia on the one hand or the United States on the other. This is not to say that they are evenly balanced either militarily or economically; the United States and its allies clearly massively outweigh Russia on both counts.

Yet this is not the end of the matter. Imperialist conflicts do not simply disappear because one side is stronger than the other. As we have already insisted, imperialism is a system, not a boxing match. In particular, tensions and conflicts arise as the parameters of competition between capitals shift.

In the current conflict between the West and Russia, each has its own vulnerabilities and its own respective advantages and weaknesses. Some are obvious. The dream of the neoconservatives’ “New American Century” lies in ruins on the battlefields of Iraq, Afghanistan and Syria. The US relies heavily on its military advantage to compensate for its relative loss of economic dominance since the Second World War. However, this military advantage has diminishing returns the nearer a conflict zone is to the borders of growing or resurgent rival powers such as China or Russia. The US suffers from overstretch, and NATO has gone to great lengths to avoid getting dragged into putting boots on the ground in Ukraine.

Russia on the other hand has difficulties of its own; its military re-equipment is extremely uneven and beset with problems. Russian growth has gone into reverse and, however popular Putin may appear, past experience shows that getting involved in a war during an economic downturn can soon change that. Some 50,000 people demonstrated in Moscow against war a day before the Crimean referendum. They not only opposed war but many, possibly a majority, opposed the annexation of Crimea itself-an impressive position to take in the circumstances and one that shames many on the Western left.32

In this respect both the West and Russia face the same difficulty. The role of the anti-war movement in limiting US, British and allied intervention in Syria and Iran and the huge scale of opposition to the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq are generally acknowledged. Despite the image of a Russian population that adores Putin for restoring Russia’s imperial pride, Putin fears he would face serious trouble if Russia were to get bogged down in Ukraine.

On the face of things there appears to be a high level of popular support for Putin’s warmongering in eastern Ukraine. However, this is deceptive on a number of counts. It is true that when polled over 50 percent of Russians said Russia should give support to the separatist leadership and the fighters in Donetsk and Luhansk, with 20 percent opposed and 20 percent unsure. However, while 40 percent supported sending troops, 45 percent were opposed.33 (Another indication of the potential opposition to Putin is the anger among families and relatives at the secrecy and intimidation surrounding the scores of deaths of Russian soldiers in Ukraine while “on holiday”).34

The first point to make is that such views in current circumstances, with a deluge of government controlled media propaganda and a weakly organised anti-war movement, are incredibly impressive. However, even more significant are the views among youth. Another poll shows the percentage of 18 to 30 year olds opposed to giving any support to the separatists exactly matching those in favour, at 41 percent.35

Limitations on their ability to achieve quick victories on the battlefield and the risk of mass opposition at home have led both the West and Russia to place great reliance on proxies in their imperialist ventures. The fostering of sectarian, national and ethnic division attains absolute primacy in these conditions, even when unintended consequences such as in Iraq, Syria and Ukraine pose immense difficulty for the ruling class. Such a strategy is highly unpredictable, partly because it involves supporting actors whose own reactionary ideologies often lead them to defy their imperialist patrons. One thing is predictable, however-such a strategy has proved its weight in gold in destroying any prospect of united resistance from below against the ruling class and against imperialism. For this our rulers will pay the price of any “local difficulty”.

Whether they get away with it depends in part on the opposition they face, and on the politics of the left and the international anti-war movement. Thus it is critical we understand what is happening in Ukraine and how the left should respond.

Crimea and the east

The ousting of Yanukovych and the collapse of the Party of the Regions had massive consequences. Russia’s strategy had been to keep Ukraine, if not firmly within the Russian sphere, at least out of the Western alliance.36 This was now in jeopardy. The West threw its support behind Kiev, turning a blind eye to the absolutely reactionary character of the regime and the role of Svoboda and the Right Sector.

This continued through the massacre of anti-Kiev Russian nationalists in Odessa on 2 May. Over 3,000 have been killed and a million displaced in eastern Ukraine as a result of the so-called “Anti-Terrorist Operation”. Disaffection within the ranks of the Ukrainian military and their families, and the dilapidated state of the Ukrainian armed forces has forced Kiev to rely on using the Nazis of the Right Sector and other militia formations. Kiev is now detested in the east, particularly in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions, including by many who were previously divided in their loyalties. The divisions between workers in Ukraine now run very deep.

Nonetheless, it is a mistake to see the movement in the east as anti-fascist or any less reactionary than its stronger counterpart in the west. The annexation of Crimea by Russia was key. Crimea houses Russia’s vital naval base on the Black Sea, leased from Ukraine. It has been the touchstone for Great Russian chauvinists since the 1980s. Year after year there have been demands, including from within the Kremlin and the Russian parliament, to annex Crimea.37 This has never had anything to do with the right to self-determination of an oppressed minority, which Russian speakers in Ukraine were not, and everything to do with exerting Russian dominance, not only over Ukraine itself but across Russia’s entire periphery.

It was in Crimea that the networks who had earned their military spurs in previous proxy conflicts helped build a political bridgehead for Russia in Crimea and afterwards in eastern Ukraine. These included the deeply reactionary Sergei Aksyonov who took the post of prime minister of Crimea, despite his party only getting 4 percent in the 2010 election; Igor Girkin (also known as Strelkov, “rifleman”), Alexander Borodai, Igor Bezler and Vladimir Antyufeyev were all veterans of previous conflicts, particularly in Transnistria. Antyufeyev, the lesser known but possibly the more significant current figure, served as security chief in Transnistria and was involved in a failed coup attempt in Latvia in 1991.

After the Crimean annexation Girkin and Borodai both moved to eastern Ukraine, where they took the leadership positions of the separatists. Their connections were critical in ensuring a flow of arms, supplies and volunteer fighters from Russia. There is no doubt that the separatists have won an important level of support as a result of political opposition to the government in Kiev and the slaughter initiated by Kiev in the east but this does not alter the fact that they can only exist as a proxy for Russian interests in Ukraine. Active support for the fighters has been limited; Girkin himself complained vehemently of this, accusing Ukrainians in the east of being cowards.

In June 2013 Girkin contributed to a round table held by a pro-Kremlin Russian news agency on Russian military strategy. His central thesis was that Russia needed to wage a new type of war modelled on the “pre-emptive” strikes mounted by Israel against enemies beyond its borders. Incidentally, he went on to talk of the “demographic decomposition of Russian society” among ethnic Russians outside Russia as well as inside; he complained of the threat of immigration and radical Islam, and how the Bolsheviks had succeeded in 1917 supported by “covert and secret international structures” (Jews) because action was not taken early enough to “neutralise” the enemy.38

Some on the left seem to be almost willingly fooled by the “anti-fascist” rhetoric of the separatists without understanding that this rhetoric has a long Stalinist and reactionary pedigree. It was used against the East German uprising of 1953 and the Hungarian Revolution in 1956; it was used again by the Warsaw Pact powers to justify support for the invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968. The charge of “national fascism” has been used to try and whip up Russian antagonism towards the independence movements in the former Soviet republics ever since the end of the 1980s.

This is a much deeper issue than the reactionary predilections of a few individuals. The very character and politics of the separatist movement are based on Great Russian chauvinism and ethnic division, notwithstanding the popular support they have achieved. In fact while the separatists secured substantial passive support against Kiev they never mobilised a mass uprising. The fighting forces and even the largest demonstrations were simply not of that order. They never managed to extend or sustain the occupations beyond some towns and cities in the two regions where the ethnic Russian population is highest.

Both the West and Russia have supported their respective proxies in Ukraine and the result has been a carnival of reaction on both sides of the conflict. Both camps have driven divisions between Ukrainian workers and in doing so strengthened the grip of the rival imperialisms over the whole working class. The pretence of some on the European and Russian left that the movement in the east is based on a progressive articulation of class demands is spurious. It is the subjective absence of a class movement in Ukraine that has allowed both these minority chauvinisms to dominate Ukraine’s political landscape with such disastrous consequences.

Imperialism and the left

A debate has emerged on the left over how to respond to Russia’s role in the conflict. Behind these debates lie differences in approach to the understanding of imperialism in general and, among Marxists, how we should apply our understanding of the classic theory of imperialism developed by revolutionaries in the early 20th century.

The dominant response, rightly, has been to oppose any interference and intervention on the part of NATO. This has to be the starting point for revolutionaries and anti-war activists in Britain. Disagreements over Russia’s role cannot be allowed to impede a united response to our own warmongers, whose hypocrisy is beyond satire. President Obama declared on Russia’s annexation of Crimea, “Sending in troops and, because you’re bigger and stronger, taking a piece of the country-that is not how international law and international norms are observed in the 21st century.” Clearly 21st century norms do not apply to Afghanistan, Iraq or Gaza.

However, this cannot be a reason for socialists to downplay the character of the conflict or Russia’s role. To do so can only undermine building an international movement against war in the long run. The difficulty begins with a tendency to view Russia’s role through the lens of US military dominance alone. Thus some of the most principled and longstanding opponents of US and British imperialism have argued that Russia is not a culpable party to the conflict or that it is on the “defensive” against the US and NATO. Such positions have been articulated, with different degrees of emphasis, by Noam Chomsky, John Pilger, Jonathan Steele and Seamus Milne of the Guardian and Stephen F Cohen, the bane of US Cold War ideologues.39 This is understandable if mistaken; however, such positions extend to sections of the left who invoke the revolutionary tradition and this has particular consequences for the left in Russia and the former Communist bloc. Within the anti-war movement treating the conflict as an inter-imperialist one has been discouraged, on the grounds that we should concentrate all our fire on our own imperialists and refrain from criticising Russia’s role.40

However, Russia is not Iraq or Afghanistan and cannot be viewed solely in an isolated relationship to US power and NATO expansion.41 Russia occupies a vast territory and has its own imperialist interests both in its own region and in other parts of the world including the Middle East. It is a contender, albeit a weak one, in the imperialist world system. Russia is part of a world system of competing capitals and seeks to compete with rival powers in order to dominate and oppress its own workers and people and those of its “near abroad” in particular. Russia is still the world’s second nuclear power.

It is essential not to confuse inter–imperialist conflicts between rival imperialist powers with conflicts between major powers and subordinate or oppressed states. If in the latter case we were to oppose both belligerents equally, we would in effect end up supporting the most powerful. However, it is a mistake to approach an inter-imperialist conflict as if it was a conflict between an imperialist and a subordinate state.

The danger, as in the Cold War, is a descent into “campism”, in which one imperialism is seen as a more or less welcome “counterweight” to the other. Here socialists and anti-war activists can be trapped into a position of justifying the ventures of “the least bad” of the rival powers. Such is the position some have taken over both the annexation of Crimea and the separatists in east Ukraine.42 The danger here is that the anti-imperialist principle so essential to building a mass anti-war movement can become discredited. It also implies that socialists in “the least bad” imperialism are exempt from arguing that “the main enemy is at home”. Meanwhile those who hold to opposing their own imperialists, but take a “campist” position, risk falling into ever deeper apologetics on the one hand or, as in the Cold War, suddenly switch position when support for a rival imperialism is no longer tenable.

An insistence on the imperialist character of the rivalry between the great powers is not an abstraction. Nor does it imply a “neutral” position. On the contrary, in the case of Ukraine, it means that even if we suspend reality for a moment and assume Russia were the dominant expansionist power, we would still be absolutely opposed to NATO intervention or sanctions. Opposition to our own imperialists does not rest on having to disguise the role of its rivals.

Above all, it is only by insisting that we face an imperialist war that it makes sense to argue, in every country, that the main enemy is at home. The aim for socialists is not only to oppose war but to turn the war between nations into a civil war between classes; to unite the workers of every country against the international “gang of robbers”.

The position of Russian socialist Boris Kagarlitsky illustrates the problem of excluding Russia from the equation, especially given the pressures on the left in the post-Soviet states. Kagarlitsky was a prominent radical dissident in the 1980s and played an important role in first advocating perestroika and glasnost “from below”. He had a high profile internationally and was prominent at anti-capitalist and anti-globalisation forums. However, Kagarlitsky’s vulnerabilities were evident before the Ukraine crisis. He took a dismissive attitude towards the huge “Bolotnaya” protests in 2011 against fraud in the Russian presidential elections, casting them simply as “middle class” protests divorced from the concerns of workers (this is a theme of Kagarlitsky’s that he took up again in the case of Ukraine).43

Unfortunately, far from arguing that in Russia, as in Britain, “the main enemy is at home”, Kagarlitsky has contented himself with attacking NATO while supporting Russia’s proxies in eastern Ukraine and praising the ethnic Russians in Crimea.44 Indeed he has criticised Putin for not intervening forcefully enough and opposed the 26,000 strong anti-war protest in Moscow on 21 September 2014.45 This is a tragic political position to hold but one in which the Western left also bears some responsibility.

In Ukraine itself the left is disastrously split. One organisation, “Borotba”, with a strong Stalinist tradition has collapsed into an alliance of Stalinists and Great Russian chauvinists and called for support for the eastern separatists. Another section, associated with the Fourth International, oriented on the movement that arose out of the Maidan protests. Unfortunately, the latter directed their main arguments against Russia rather than the deep illusions in NATO and the EU in western Ukraine. In the West too the Maidan attracted the hopes of those who elevated the “spontaneous” character of Occupy and other social movements with some casting Russia as the main enemy and Western imperialism as a mere bit player.46

Conclusion

While we can speculate as to the outcome of the current ceasefire, what is clear is that economic crisis and imperialist rivalry have deeply divided Ukraine. Nonetheless, the objective potential for a united response by workers in the east and west continues to exist. This will depend upon whether a movement and force on the left begins to emerge that challenges not only the oligarchs but the rival imperialisms and the rival national chauvinisms they have fuelled.

To side with one chauvinism or another in Ukraine or paint one side or another in fake socialist colouring or to argue that one imperialist camp is defensive is to defy the lessons drawn by revolutionaries in the First World War.

It is true that socialists in Ukraine, in Russia and here in the West face different concrete tasks. However, these tasks are informed by two common principles: first, recognition that this is an imperialist conflict; second, that socialists strive to forge the international unity of the working class across every national and ethnic divide. It is from these principles that uncompromising opposition to our own rulers’ rivalry in Ukraine flows, while at the same time making no concession to their imperialist rivals or their proxies. This is as true in London as it is in Moscow, Kiev or Donetsk.

In his pamphlet “Socialism and War”, Lenin argues:

From the standpoint of bourgeois justice…Germany would be absolutely right as against England and France, for she has been “done out” of colonies, her enemies are oppressing an immeasurably far larger number of nations than she is, and the Slavs who are oppressed by her ally Austria undoubtedly enjoy far more freedom than those in tsarist Russia, that real “prison of nations”. But Germany is fighting not for the liberation, but for the oppression of nations.

Lenin goes on to argue that it is not the business of socialists to help one robber rob another: “Socialists must take advantage of the struggle between the robbers to overthrow them all. To be able to do this, the Socialists must first of all tell the people the truth, namely, that this war is in a treble sense a war between slave-owners to fortify slavery”.47

The lessons learnt in forging a united international workers’ movement in the teeth of war, crisis and national chauvinism on the monumental scale that existed in the First World War needs to be relearnt. The long decades of low levels of class struggle and the rise and fall of the movements have exacted a political price on the left, leading many to turn to other social forces to bring change. Ultimately this leads to the danger of compromise with the existing system itself. Nowhere is this task more urgent than over the question of Ukraine.

The failure to grasp the character of state capitalism in Russia after Stalin’s counter-revolution has also returned to haunt us. During the Cold War Tony Cliff first used the slogan: “Neither Washington, Nor Moscow but International Socialism!” to restore the principled positions taken by Lenin and the Bolsheviks during the First World War. Cliff did so in a situation where the left internationally took a “campist” position in favour of supporting one imperialism or another, in particular the state capitalist Soviet empire, and turned their backs on an international working class that had the capacity to bring ruin to their own imperialists, and to the entire “gang of robbers”. It is a position the left needs to re-learn in the context of a multi-polar world of rival capitals and states:

In their mad rush for profit, for wealth, the two gigantic imperialist powers are threatening the existence of world civilisation, are threatening humanity with the terrible suffering of atomic war. The interests of the working class, of humanity, demand that neither of the imperialist world powers be supported, but that both be struggled against. The battle-cry of the real, genuine socialists today must be:

“Neither Washington nor Moscow, but International Socialism”.48

Notes

1: Lenin, 1917.

2: Lenin, 1914.

3: Cumming-Bruce, 2014, and UN High Commissioner for Refugees, 2014.

4: Stratfor, 2014a.

5: Lieven, 1999, pp7-9. Lieven is not of the left but has written interesting and informed work on Chechnya and Ukraine.

6: For a discussion of how the classic theories of imperialism should be applied, see Harman, 2003. Elsewhere Harman specifically addresses the argument that Russia cannot be seen as an imperialist power (Harman, 1980) and takes a critical look at Nikolai Bukharin’s approach (Harman, 1983). Also see the debate between Alex Callinicos and Leo Panitch and Sam Gindin (Callinicos, 2005; Panitch and Gindin, 2006; Callinicos, 2006). On the latter debate also see Rees, 2006, pp212-17 (this is of particular interest in the light of recent differences between myself and John Rees over Ukraine).

7: Communist Party of the Soviet Union, 1939, pp331-52. This final chapter of “The Short Course”, The History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks) begins with the international situation and concludes with the “Liquidation of the Remnants of the Bukharin-Trotsky Gang of Spies, Wreckers and Traitors”.

8: Trotsky predicted an alliance between Stalin and Hitler in 1937, documenting attempts by Stalin to reach an understanding with the Nazi regime—Dewey Commission, 1937. Also Broué, 1997, p716. Pierre Broué argues that the purges of the Polish Communist Party were motivated in part by Stalin’s need to clear the path for a deal with the Nazis to carve up Poland; under the terms of the pact Stalin seized the Ukrainian regions of Galicia and Volhynia, including Lviv. If Broué is right, similar calculations would have applied to the Ukrainian Communists. I am grateful to Gareth Jenkins for this reference.

9: Trotsky, 1939.

10: Garnett, 1997; Lieven, 1999. See also Goodby, 1998. For a strong post-Maidan analysis from the same “realist” school see Trenin, 2014.

11: Harman and Zebrowski, 1988; Harman, 1990. These two articles, written as the Soviet Union entered its final collapse, contain a classic analysis of the roots of the crisis, and the part played by the national movements in the former Soviet republics.

12: Krawchenko, 1993.

13: Gillman, 1998, p398.

14: 1,300 Ukrainian Hryvnia, about £62 at the time of writing.

15: Vladimirovich, 2011.

16: Rudling, 2013, pp228-231.

17: Pew Research Centre, 2014, p10.

18: Fisher, 2013.

19: Centanni, 2014.

20: Lieven, 1999, p16.

21: Diuk, 2012, pp120-121.

22: Pew Research Centre, 2014, p4

23: Rao, 2013.

24: Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Foundation, 2014.

25: Cadier, 2014.

26: Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Foundation, 2014.

27: Stewart, 1997, pp18-21.

28: Although in the case of the ECU, the balance of trade is overwhelmingly with Russia. Belarus and Kazakhstan remain bit players.

29: Cadier, 2014.

30: Even in the case of Chechnya, Putin learnt from the experience of the defeat of 1994-6. He took great care at the beginning of the war to foster a strong, local Chechen regime under a former rebel, the brutal Akhmat Kadyrov, succeeded after his assassination in 2004 by his equally brutal and corrupt son, Ramzan. Putin poured billions of dollars into the reconstruction of Grozny in order to cement their rule.

31: For an account of the war in Chechnya and the conflicts of the 1990s, see Ferguson, 2000.

32: The demonstrations were impressive but revealed the weakness of the Russian left which only numbered a few hundred. This has serious consequences for a movement whose political orientation is largely dominated by free market liberals.

33: Levada, 2014.

34: Schlossberg, 2014a and 2014b.

35: Goryashko, 2014.

36: See for example, Stratfor, 2014b.

37: Stewart, 1997, pp21-6.

38: Investigate This, 2014.

39: Chomsky, 2014; Pilger, 2014; Milne, 2014; Steele, 2014; Vanden Heuvel and Cohen, 2014.

40: German, 2014; Nineham, 2014.

41: See Nineham, 2014 for a comparison of positions on Russia to, for example, Serbia.

42: Kagarlitsky, 2014a; 2014b; 2014c; 2014d; 2014e.

43: Kagarlitsky, 2011. See also Haynes, 2008; Crouch, 2002; Harman, 1994 and Callinicos, 1990 for criticisms of key aspects of Kagarlitsky’s approach, not least on the national question and his ambiguous position regarding the Russian “left”.

44: Kagarlitsky, 2014a; 2014b; 2014c; 2014d; 2014e.

45: Rabkor, 2014.

46: Zizek, 2014.

47: Lenin, 1915.

48: Cliff, 1950.

References

Broué, Pierre, 1997, Histoire de L’Internationale Communiste: 1919–1943 (Fayard).

Cadier, David, 2014, “Eurasian Economic Union and Eastern Partnership: the End of the EU-Russia Entredeux”, LSE (27 June), www.lse.ac.uk/IDEAS/publications/reports/pdf/SR019/SR019-Cadier.pdf

Callinicos, Alex, 1990, “A Third Road?”, Socialist Review (February), www.marxists.org/history/etol/writers/callinicos/1990/02/3rdroad.html

Callinicos, Alex, 2005, “Imperialism and Global Political Economy”, International Socialism 104 (autumn), www.isj.org.uk/?id=140

Callinicos, Alex, 2006, “Making Sense of Imperialism: a Reply to Leo Panitch and Sam Gindin”, International Socialism 110 (spring), www.isj.org.uk/?id=196

Centanni, Evan, 2014, “How Sharply Divided is Ukraine, Really? Honest Maps of Language and Elections” Political Geography Now (9 March), http://tinyurl.com/orv5vgm

Chomsky, Noam, 2014, “Interview: Noam Chomsky”, Chatham House (June),

www.chathamhouse.org/publication/interview-noam-chomsky#

Cliff, Tony (as R Tennant), 1950, “The Struggle of the Powers”, Socialist Review (November), www.marxists.org/archive/cliff/works/1950/11/powers.html

CPSU, 1939, History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks) (Foreign Languages Publishing House).

Crouch, Dave, 2002, “The Inevitability of Radicalism”, International Socialism 97 (winter),

www.marxists.org/history/etol/newspape/isj2/2002/isj2-097/crouch.htm

Cumming-Bruce, Nick, 2014, “More than a Million Ukrainians have been Displaced, UN says”, New York Times (2 September), http://tinyurl.com/jwgx7pn

Dewey Commission, 1937, “The Case of Leon Trotsky, 8th Session” (14 April), http://tinyurl.com/qfjmeec

Diuk, Nadia M, 2012, The Next Generation in Russia, Ukraine, and Azerbaijan: Youth, Politics, Identity and Change (Rowman and Littlefield).

Ferguson, Rob, 2000, “Chechnya: The Empire Strikes Back”, International Socialism 86 (spring), www.marxists.org/history/etol/newspape/isj2/2000/isj2-086/ferguson.htm

Fisher, Max, 2013, “This One Map helps explain Ukraine’s Protests”, Washington Post

(9 December), http://tinyurl.com/op4s9ce

Garnett, Sherman W, 1997, Keystone in the Arch: Ukraine in the Emerging Security Environment of Central and Eastern Europe (Carnegie).

German, Lindsey, 2014, “Does Opposing our Government’s Wars mean we Support ‘the Other Side’?” (13 July), http://tinyurl.com/knsfch7

Gillman, Max, 1998, “A Macroeconomic Analysis of Economies in Transition”, in Amnon Levy-Livermore (ed), Handbook on the Globalization of the World Economy (Edward Elgar).

Goodby, James E, 1998, Europe Undivided: The New Logic of Peace in US–Russian Relations (United States Institute of Peace Press).

Goryashko, Sergei, 2014, “Russians do not Understand the Objectives of the Lugansk and Donetsk Republics”, Kommersant (4 September).

Harman, Chris, 1980, “Imperialism, East and West”, Socialist Review (February), www.marxists.org/archive/harman/1980/02/imp-eastwest.htm

Harman, Chris, 1983, “Increasing Blindness”, Socialist Review (June), www.marxists.org/archive/harman/1983/06/bukharin.htm

Harman, Chris, 1990, “The Storm Breaks”, International Socialism 46 (spring), www.marxists.org/archive/harman/1990/xx/stormbreaks.html

Harman, Chris, 1994, “Unlocking the Prison House”, Socialist Review (July/August), www.marxists.org/archive/harman/1994/07/centasia.html

Harman, Chris, 2003, “Analysing Imperialism”, International Socialism 99 (summer),

www.marxists.org/archive/harman/2003/xx/imperialism.htm

Harman, Chris, and Andy Zebrowski, 1988, “Glasnost-Before the Storm”, International Socialism 39 (summer), www.marxists.org/archive/harman/1988/xx/glasnost.html

Haynes, Mike, 2008, “Valuable but Flawed”, International Socialism 119 (summer), www.isj.org.uk/?id=471

Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiatives Foundation, 2014, “Maidan 2013: Who, Why and for What?” http://dif.org.ua/ua/events/gvkrlgkaeths.htm

Investigate This, 2014, “Ukraine Crisis: Militia Leader Igor Girkin a Hardline Russian Ex-FSB Colonel (Updated)” (15 August), http://tinyurl.com/lbqf4xd

Kagarlitsky, Boris, 2011, “Boris Kagarlitsky: A Very Peaceful Russian Revolt”, Links: International Journal of Socialist Renewal (11 December), http://links.org.au/node/2663

Kagarlitsky, Boris, 2014a, “Boris Kagarlitsky: Crimea Annexes Russia”, Links: International Journal of Socialist Renewal (24 March), http://links.org.au/node/3790

Kagarlitsky, Boris, 2014b, “Boris Kagarlitsky on Eastern Ukraine: The Logic of a Revolt”,

Links: International Journal of Socialist Renewal (1 May), http://links.org.au/node/3838

Kagarlitsky, Boris, 2014c, “Solidarity with the Anti-fascist Resistance in Ukraine Launch”, (Video Link with Boris Kagarlitsky-2 June), http://tinyurl.com/lg52v87

Kagarlitsky, Boris, 2014d, “Boris Kagarlitsky: Eastern Ukraine People’s Republics between Militias and Oligarchs”, Links: International Journal of Socialist Renewal (16 August), http://links.org.au/node/4008

Kagarlitsky, Boris, 2014e, “Ukraine’s Uprising against Nato, Neoliberals and Oligarchs-an Interview with Boris Kagarlitsky”, Counterfire (8 September), http://tinyurl.com/pgnpn64

Krawchenko, Bohdan, 1993, “Ukraine: the Politics of Independence”, in Ian Bremmer and Ray Taras (eds) Nations and Politics in the Soviet Successor States (Cambridge University Press).

Lenin, V I, 1914, “Letter to A.G. Shlyapnikov” (17 October), http://tinyurl.com/phfy3gd

Lenin, V I, 1915, “Socialism and War” (July-August), http://tinyurl.com/nmq7nrq

Lenin, V I, 1917, “In the Footsteps of Russkaya Volya” (13 April), http://tinyurl.com/psufcxc

Levada, 2014, “Russian Views on Events in Ukraine” (27 June), http://tinyurl.com/on2w23s

Lieven, Anatol, 1999, Ukraine and Russia: a Fraternal Rivalry (United States Institute of Peace Press).

Milne, Seamus, 2014, “It’s not Russia that’s Pushed Ukraine to the Brink of War”, (30 April), www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/apr/30/russia-ukraine-war-kiev-conflict

Nineham, Chris, 2014, “Ukraine: Why Being Neutral Won’t Stop a War”, (23 March),

www.counterfire.org/articles/analysis/17119-ukraine-why-being-neutral-wont-stop-a-war

Panitch, Leo, and Sam Gindin, 2006, “Feedback: Imperialism and Global Political Economy-a reply to Alex Callinicos”, International Socialism 109 (Winter), www.isj.org.uk/?id=175

Pew Research Centre, 2014, “Despite Concerns about Governance, Ukrainians Want to Remain One Country”, Pew Research Global Attitudes Project (8 May), http://tinyurl.com/pxayt3u

Pilger, John, 2014, “In Ukraine, the US is Dragging us Towards War with Russia”, Guardian

(13 May), http://tinyurl.com/le5v6h4

Rabkor, 2014, “Anti-fascists were Removed by Police from the ‘Peace March’ in Moscow, Rabkor (21 September), http://rabkor.ru/news/2014/09/21/peace-march

Rao, Sujato, 2013, “Banks Cannot Ease Ukraine’s Reserve Pain”, Global Investing (9 December), http://blogs.reuters.com/globalinvesting/2013/12/09/banks-cannot-ease-ukraines-reserve-pain/

Rees, John, 2006, Imperialism and Resistance (Routledge).

Rudling, Per Anders, 2013, “The Return of the Ukrainian Far Right: The Case of VO Svoboda”, in Ruth Wodack and John E Richardson (eds), Analysing Fascist Discourse: European Fascism in Talk and Text (Routledge).

Schlossberg, Leo, 2014a, “The Army and the Volunteers”, Novaya Gazeta (3 September).

Schlossberg, Leo, 2014b, “They weren’t just Tricked, They were Humiliated”, Novaya Gazeta

(4 September).

Steele, Jonathan, 2014, “The Ukraine Crisis: John Kerry and Nato must Calm Down and Back Off”, Guardian (2 March), http://tinyurl.com/mped2pn

Stewart, Dale B, 1997, “The Russian-Ukrainian Friendship Treaty and the Search for Regional Stability in Eastern Europe (Thesis)”, Monterey Naval Postgraduate School (December), https://archive.org/details/russianukrainian00stew

Stratfor, 2014a, “Potential New Dangers emerge in the US-Russian Standoff” (3 September), http://tinyurl.com/l8usyt5

Stratfor, 2014b, “Ukraine: Russia Looks Beyond Crimea” (3 March), http://tinyurl.com/ktjaybx

Trenin, Dmitri, 2014, “The Ukraine Crisis and the Resumption of Great Power Rivalry”, Carnegie Moscow Center (9 July), http://tinyurl.com/kc9uwul

Trotsky, Leon, 1939, “The Problem of the Ukraine”, Socialist Appeal (9 May), www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1939/04/ukraine.html

UNHCR, 2014, “Number of Displaced inside Ukraine more than Doubles Since early August to 260,000” (2 September), www.unhcr.org/540590ae9.html

Vanden Heuvel, Katrina, and Stephen F Cohen, 2014, “Cold War Against Russia-Without Debate”, The Nation (19 May), http://tinyurl.com/kmnx48d

Vladimirovich, Smetanin Ihor, 2014, “Coal miner: People are Expendable”, Kyiv Post

(5 August), http://tinyurl.com/lg3w963

Zizek, Slavoj, 2014, “What Europe Can Learn from Ukraine”, In These Times (8 April),

http://inthesetimes.com/article/16526/what_europe_can_learn_from_ukraine