“We are on the edge of the abyss. One slip and we will be into depression like that of the early 1930s.” That message has been repeated a thousand times in one way or another since the banking system imploded and stock markets sank in September and October 2008. However, there has been very little real analysis of what produced the great slump or of the real comparisons with the situation today.

The slump of the 1930s was by far the worst that capitalism had ever known. It cut industrial output by half in the world’s two biggest economies, the US and Germany, and made about a third of workers unemployed in each case. It was by far the most significant economic event of the 20th century. Yet coming to terms with the slump has been the great problem of mainstream economics. Ben Bernanke, head of the US federal reserve bank, is meant to be one of the mainstream experts on it. He calls the explanation the “Holy Grail” of economics1—something sought after but never found. Nobel economics laureate Edward C Prescott describes it as a “pathological episode and it defies explanation by standard economics”.2 For Robert Lucas, another Nobel laureate, “it takes a real effort of will to admit you don’t know what the hell is going on”.3

The course of the slump

Most popular comment on the slump sees its origins in the Wall Street Crash of October 1929. From this it is easy to draw the conclusion that the recession we are entering today is equally the product of the financial crisis. But the US economy was moving into recession before the Wall Street Crash. There was the beginning of a recession in 1927, but this came to an end with a brief upsurge of industrial investment. By early summer 1929 this surge had come to an end, and by July and August production was falling. “Business was in trouble before the crash”.4

This in itself was bound to have an impact on the global economy, since the US at the time accounted for half of world industrial production. But it was not only in the US that recession began before the crash. It did so also in continental Europe. Conditions were worst in Germany, the world’s second biggest industrial economy, which began experiencing an economic downturn in 1928: “Many German industries were reaching a saturation point in the rationalis-ation programme which followed in the wake of the world war and were approaching the end of the job of capital rebuilding… Forces were working to produce a sharp decline in the volume of American investments abroad”.5 “By the summer of 1929 the existence of depression was unmistakable”6 as unemployment reached 1.9 million and the spectacular failure of the Frankfurt Insurance Company began a series of bankruptcies. The Belgian economy started declining from March 1929 onwards and had fallen 7 percent by the end of the year, while in Britain the turning point came in July. Only in France was production still rising at the time of the crash. In fact, one of the factors that had fuelled the US stock exchange boom in the run up to the crash was the return of American funds that had been used for short term investment in Germany as investment opportunities there became limited.

If the US crisis began before the stock exchange crash, many commentators think its direct impact was also very limited. Barry Eichengreen holds that “economic historians long ago dismissed the crash as a factor in the decline of output and employment, on the grounds that equities were only a fraction of total household wealth and that the marginal propensity to spend out of wealth was small”.7 Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz argued it was “a symptom of the underlying forces making for a severe contraction in economic activity…but its occurrence must have helped deepen the contraction”.8

At first the crisis seemed like a typical short-term recession. In the first 12 months industrial production fell by about 20 percent and unemployment rose 16 percent in the US. These figures are many times worse than we have experienced in any of the recessions since the Second World War. But they were, up to this point, only about as severe as in recessions in 1893-4, 1907 and 1920-1, from which there had been quite rapid recovery.9 Major employers assumed things would be the same again as interest rates fell rapidly. There were an increasing number of failures of local banks, but this did not stop a small increase in output in the first months of 1931.

Then a second phase of the crisis began under the impact of the parallel crisis developing in Europe. In May Austria’s biggest bank, the Credit Anstalt, went bust—and caused major difficulties for German banks that had made loans to it. The problems in each country impacted on those in others. Britain was hit by the withdrawal of foreign funds from its banks, and the British Labour government collapsed in late August. When the new national government broke with the world monetary structure based on the gold standard this created vastly exaggerated fears in the US. The Federal Reserve Bank raised interest rates to protect the value of the dollar; there was “a spectacular increase in bank failures”10 and industrial production fell to a devastating 40 percent below its 1929 figure. Money incomes were falling by 31 percent a year although the effect on the living standards of people with jobs was mitigated by prices falling by about 14 percent.

Even so there was another illusion of recovery in the first half of 1932 with a small rise in factory employment, and industrial production began to rise. “The economic situation as a whole in the early fall of 1932 showed the first widespread and definite upturn since 1929”.11

It was the lull before the storm: “A fresh wave of panic developed late in 1932, however, apparently due to the misgivings of business management and propertied people over the result of the election… After the turn of the year the situation went rapidly from bad to worse”.12 A further 462 banks—about one tenth of the total—suspended operations between the beginning of 1933 and March that year, by which time industrial output was down to half the pre-slump level.

It was at precisely this point that Franklin D Roosevelt was inaugurated as US president and was forced by the sheer intensity of the crisis to take much more radical measures than he had intended, rushing emergency economic legislation through Congress. His New Deal is often seen as marking the end of the slump. It certainly represented an important shift in government policy, with a recognition that capitalism in its monopoly stage could no longer solve its problems without systematic state intervention. To that extent it marked a watershed between two phases in the development of the system. But the precise degree of state control of capitalism was limited.

The Federal Reserve guaranteed the funds of the remaining banks to prevent further collapse. Government money bought up and destroyed farm crops in order to raise prices. A civil construction corps provided work camps for 2,300,000 young unemployed men. The National Recovery Act provided for a limited form of self-regulation for industry through encouraging the formation of cartels, which could control prices and production levels, while it also made it a little easier for unions to raise wages (and so consumer demand). There was a limited experiment in direct state production through the Tennessee River Authority. At the same time, the government withdrew the US from the gold standard, so the value of the dollar and the level of funds in the US no longer depended purely on the free flow of the market but upon conscious government intervention designed to aid US exports. In these ways the state tried to boost the private sector. But it did not impose its own control. Even “fiscal means to expand employment remained limited since the Democratic administration under Roosevelt remained committed to balanced budgets”.13

Such timidity could have only a limited impact on the crisis. There was a new upturn in the economy from March 1932 through to the end of the summer. But it was “neither widespread nor rapid”14 and industrial production after rising began to slide back the following year, leaving 12 million still jobless. It was not until 1937 that production reached the 1929 figure. There was still 14.3 percent unemployment—and this “miniboom” soon gave way to “the steepest economic decline in the history of the US”, which “lost half the ground gained…since 1932”.15 Unemployment rose again to 19 percent and was still at 14 percent on the eve of US entry into the war in 1940. The greatest slump capitalism had known was not ended by government action. The most this may have achieved was to replace continual decline by long stagnation, leaving a very high level of unemployment and output below that of the previous decade.16 JK Galbraith summed the situation up when he wrote, “The Great Depression of the thirties never came to an end. It merely disappeared in the great mobilisation of the forties”.17

Mainstream explanations for slump

There have been attempts at explanation. The English economist Arthur Cecil Pigou articulated what became the most widely accepted version. Workers, he argued, had priced themselves out of their jobs by not accepting cuts in their money wages. Had they not done so, the magic of supply and demand would have solved all the problems. Irving Fisher, a prominent American neoclassical economist, belatedly provided a monetarist interpretation, arguing that the money supply was too low, leading to falling prices, over-indebtedness and bankruptcies. More recent “monetarist” theorists put the blame on the behaviour of the central bankers. If only, the argument goes, the US Federal Reserve Bank had acted to stop the money supply contracting in 1930 and 1931, then everything would have been all right. The arch monetarist of the post-war decades, Milton Friedman, traced the disaster back to the death of Federal Reserve chief Benjamin Strong in October 1928.18

By contrast Friedrich von Hayek and the “Austrian school” of economists argued that excess credit in the early 1920s had led to a disproportionately high level of investment, which only the slump itself could overcome. Accordingly, government intervention of any sort would make things worse. Still other economists blamed the dislocation of the world economy in the aftermath of the First World War or the functioning of the gold standard. John Maynard Keynes and his followers such as Alvin Hansen and Paul Samuelson saw an excess of saving over investment as leading to a lack of “effective demand” for the economy’s output. Ever since, the proponents of each view have found it easy to tear holes in the arguments of those holding the other views, with none being able to survive serious criticism.19

A Marxist explanation of the slump

The Marxist tradition of political economy can provide an understanding of the great slump, which mainstream economists cannot, by focusing on a central element in Marx’s theory—the tendency of the rate of profit to fall.

Marx argued that this tendency exists alongside the more or less regular boom-recession cycle caused by the lack of coordination of investment decisions through the system. Accumulation, Marx claimed, proceeds faster than the growth of the productively employed labour force, which is the source of surplus value. Therefore, the ratio of surplus value to investment—the rate of profit—tends to fall.20 As it falls, the spur to investment diminishes, leading to a slowdown in accumulation. The result is that recessions will get deeper as the system gets older.

There are counteracting factors. Workers can be made to work harder and longer; increased productivity in agriculture and consumer goods industries can cut the cost of providing the workers with the living standards they expect; more rapid communications can cut the costs involved in distributing and selling what has already been produced. Finally, the crisis itself, by driving some firms out of business, enables other firms to buy up their plant and equipment on the cheap just as unemployment is forcing wages down. The profit rates of the survivors can rise, so creating the conditions for a new expansion of investment and production. In this way the downward pressure on profit rates aggravates the crisis, while the crisis permits some increase in profit rates.

Marx’s argument about the rate of profit was further developed by the Polish-Austrian economist Henryk Grossman in the 1920s. He set out to refute the claim by the Austrian socialist Otto Bauer that capitalism could expand indefinitely providing the different sectors of the economy expanded in tandem with each other. Grossman showed, extending Bauer’s calculations, that eventually a point would be reached at which the decline in the rate of profit meant further investment could not take place without completely destroying the profitability of existing investment, leading capital accumulation to grind to a halt. This, he contended, confirmed Marx’s argument in volume three of Capital.21 There was, however, an ambiguity in Grossman’s argument. He suggested at some places that it led to “the breakdown of capitalism” but at others only that it made inevitable periodic crises that could act to ward off the fall in the rate of profit by destroying some capitals to the benefit of others.

How well does the great slump fit with such analyses?

Estimates of the rate of profit in the US in the decades prior to the slump by Joseph Gillman, Shane Mage, Gerard Dumenil and Dominique Levy, and Lewis Corey all suggest that it had undergone a long-term fall of about 40 percent between the 1880s and the early 1920s22—something that could be traced back to a long-term rise in the ratio of investment to the employed workforce (the “organic composition of capital”) of about 20 percent.23 Some of the estimates suggest profitability was able to make a small recovery through the 1920s but only by increasing the rate of exploitation of the workforce, with employers doing their utmost to increase the tempo of work and to prevent wage rises.24 Real wages rose by a mere 6.1 percent and total consumption by only 18 percent between 1922 and the beginning of 1929, while gross industrial production grew by about a third. The discrepancy was greatest in 1928 and 1929, with output rising three times faster than consumption.25 Michael Bernstein notes that “the lower 93 percent of the nonfarm population saw their per capita disposable income fall during the boom of the late 1920s”.26

Such an increasing gap between output and consumption had to be filled if the economy was to operate at full employment level. Increased productive investment could have filled the gap. But it only did so partially. Total real investment grew more slowly than in previous decades—about a third slower than according to Gillman’s calculation, around 50 percent slower according to Steindl: “Hardly anyone was aware during the ‘New Era’ that the annual rate of growth of business capital then was only half of what it had been 30 years earlier”.27

This account of a slowdown in investment contradicts some received wisdom. The “traditional Keynesian view traces the magnitude of the Great Depression back to the investment boom of the 1920s”.28 But this does not distinguish productive capital in industry from non-productive investment in retailing and finance,29 and it often counts domestic house building as “investment”. A breakdown of investment into its components confirms the accounts of Steindl and Gillman. Alvin Hansen analysed the “vast sum” of $18.3 billion of average annual investment between 1923 and 1929 and found that “only $9.7 billion of it was business investment (including in the commercial sector), and of that only a third was new investment”.30 More recently RJ Gordon has noted (without drawing out the full implications) that “the equipment boom of the 1920s is a pipsqueak, with a productive durable equipment share of about 5 percent”.31

The recovery of profit rates was insufficient to induce productive investment on the scale necessary to absorb the surplus value accumulated from previous rounds of production and exploitation. This was reflected in much business comment at the time about a “superabundance of capital”.32

Some firms responded by trying to find new sources of profit through very big individual investments—as when Ford set out to build its massive River Rouge auto plant, completed in 1928. There was a huge expansion of new industries that seemed to offer spectacular profits (in a way that recalls the dotcom and telecoms booms of the late 1990s), with “the pouring of new capital into the radio receiving set industry in 1928 and 1929. In the short space of 18 months the potential production of this industry was increased threefold”.33

But if some firms would undertake such new and potentially risky investments, others looked at their profit rates and chose not to. They preferred a slower tempo of accumulation, using their dominance of particular industries to keep up prices even if it meant producing well below full capacity. The result was that they did not spend enough themselves or employ enough workers to provide additional demand to absorb the output of other industries. So the big new plants that came into operation towards the end of the boom necessarily produced on too great a scale for the market, flooding it with products that undercut the prices and the profits of old plants: 15 million radio sets were being produced annually by the end of 1929 for a market that could absorb only a little more than four million.

Such underlying problems were hidden through most of the decade by upsurges in luxury consumption by the rich, by speculative non-productive investment in real estate, spending on sales promotion, and the building of retail stores. Hansen writes, “In the 1920s stimulated and sustaining forces from outside of business investment and consumption were present… Non-business capital expenditures led and helped to sustain the …recovery”.34 A massive increase in inequality (recalling the last three decades) meant that the rich and the well to do middle classes were responsible for 42.9 percent of consumption.35 According to Corey, “The equilibrium of capitalist production came to depend more and more on artificially stimulating the ‘wants’ of small groups of people with excess purchasing power.”

Alongside this went increased expenditure on trying to sell goods. Distribution costs rose to 59 percent of industrial costs by 1930, with advertising revenue alone amounting to $2 billion in 192936—only 25 percent less than total expenditure on plant and equipment in manufacturing industries. Gillman argues that “non-productive expenses” (advertising, marketing and so on) grew from half the total surplus value in 1919 to two thirds by the end of the 1920s.

A succession of speculative booms pushed stock market and real estate prices to dizzy heights. These in themselves did not absorb surplus value (they merely transferred investable funds from one set of hands to another) but they did involve a great deal of unproductive expenditure as a by-product (new buildings, salaries to unproductive personnel, conspicuous consumption). Symbolic of the level of non-productive investment was the building of the Empire State Building—completed in 1930 when the crisis was well under way. But the search for profits also led to some resources going into “productive” enterprises that could not have been thought of as profitable if a speculative climate had not existed.

An important factor, particularly in the last years of the boom, was a growth of debt. “Expansion was heavily driven by spending on consumer durables purchased on the instalment plan, using credit provided mainly by non-bank lenders… The major automobile producers established divisions and subsidiaries designed to finance purchases of their own durable goods… The consequences showed up not just in the stock market, but in the burgeoning automobile industry, the leading sector of the 1920s, and in the commercial property market, which boomed in virtually every American city”.37

But eventually a point was reached at which the underlying problems began to express themselves. House building began to decline from 1925 onwards, leading to a fall of the share of total investment in the economy “from 27.1 percent in 1925 to 24.8 percent in 1929”.38 RJ Gordon recognised how there was already “downward pressure on aggregate demand in 1929, temporarily masked by strength in consumption and inventory change, both of which were vulnerable to a multiplier contraction once investment collapsed”.39 Hansen argues that, “the ‘external forces’ collapsed in 1928 and a year after the boom was over”.40 RA Gordon writes, “The rise in the output of durable goods in 1928-9 was too rapid to be long maintained. Excess capacity was developing in a number of lines, and this meant that…new orders for some types of durable goods declined fairly early in 1929”.41

This contraction in the spring and early summer of 1929 revealed the limitations of the market for the goods being turned out by the new car and radio plants—and for the steel and electricity industries that depended on them. “Producer goods” output fell 25 percent in a year—and a further 25 percent in the year that followed.42 The fall in the productive economy necessarily led capitalists to cut back on non-productive expenditures, causing a massive fall in real estate prices and wrecking the balance sheets of banks who had lent to finance that sector,43 producing the successive waves of bank failures.

A big recession was a necessary consequence of a big boom reliant to a large extent upon non-productive expenditure and speculation to make up for deficiencies in productive investment, and on private borrowing to finance consumer consumption.44 And since the recession was in the world’s biggest industrial power—accounting at the time for about half of global industrial output and a major source of lending to the other industrial centres in Europe—it was bound to have a ricochet effect everywhere.

The picture for Germany is not radically different. Balderston quotes two different attempts to estimate profit rates for before the First World War and the 1920s. They differ considerably,45 but he concludes that there was a “failure of profits to return to their pre-war ‘normal’ level”.46 Along with low profit rates went low levels of investment—with “aggregate investment” between 1925 and 1929 at only 11 percent of net national product, as against 14 percent pre-1914 and 18 percent post-1950.47 What is more, only a small proportion was fixed investment and only about 20 percent was in industry. Most was in government run public utilities and local authority built housing. The finance minister of the time, Hjalmar Schacht, complained that an equity boom was “diverting funds from real recovery into speculation”.48 Local authorities, firms and individuals had borrowed to sustain such non-productive investment. But they found it increasingly difficult to do so. “Cuts in investment were already being experienced owing to the collapse in the domestic bond and share markets”.49 Under such circumstances it only required “a small exogenous shock” to cause “an already unstable system to collapse”.50 Real net investment fell by 14 percent in 1928, exports by 8 percent and government consumption by 3 percent in 1929, and unemployment rose from 1.4 million through 1.9 million to 3.1 million by 1930.51

The situation of the British economy, then still the world’s third largest, was slightly more complex. Far from booming, it suffered through the 1920s because of two interacting factors. The first was a decline in the rate of profit that had already begun to make its impact felt before 1914 and served to hold back investment.52 The second was the attempt to maintain its formerly global financial and political eminence by returning the pound to its pre-war exchange rate. The result was a two-decade depression in heavy industry—coal, iron and steel, shipbuilding—and unemployment even in “good years” greater than in the worst years in the previous half century.53 The effect of the recessions in the US and Germany was to add a wider crisis on to the existing crisis of these industries. But the fact that there had not been a real boom beforehand had the paradoxical effect that the slump in Britain as a whole never reached the depths of the US and Germany (although this was no compensation for those suffering in the old industries and industrial areas, where unemployment could reach 30 percent).54

Overall, the Marxist theory of the declining rate of profit can explain the outbreak of global recession. Low profitability in the three biggest economies led to a low level of productive investment, which would have meant economic stagnation had it not been for unproductive expenditures, speculative bubbles and debt based consumption and construction. But any faltering in economic growth was bound to cause a fall in these expenditures and with them a rapid fall in the markets for output of productive industry.

But this in itself does not explain why the recession turned into a slump which was so deep and endured so long. An explanation lies in something missing from Marx’s account of the crisis in Capital. It is the impact of the growth since Marx’s time of the biggest firms and their increasing weight in the system as a whole—a process Marx called the concentration and centralisation of capital.

The Bolshevik economist Preobrazhensky noted in 1931 that under “monopoly capitalism” the biggest firms are able to resist the liquidation of inefficient units of production during crises. “Monopoly capitalism continually reopens backward enterprises, whereas free competition shuts them down”.55 This produced “thrombosis in the transition from crisis to recession” and prevented—or at least delayed—the restructuring necessary for emergence from the crisis.

There were bankruptcies and business failures in 1929-33. But they were of farmers, banks, and small and medium businesses, not the giants who dominated the major industries. “The subset of corporations holding more than $50 million in assets maintained positive profits throughout this period, leaving the brunt to be borne by smaller companies”.56 The giant industrial corporations were able to keep going, running their operations at a low level and sacking workers, but not by writing off capital—while the Hoover government provided money to protect the one group of big non-banking firms that were threatened with bankruptcy, the railway companies.57 Under such circumstances the old capitalist method of recovering from the crisis by the cannibalism of some big firms by others could not work.

That explains why government intervention—”state capitalism”—in one form or another eventually became inevitable. But it also explains the limits to what such intervention could achieve so long as it left the central investment decisions in private hands. It was only when all-out war persuaded the great firms to accept government control and coordination of their investment decisions, with the US government building the factories for private capital to operate, that the slump finally came to an end.

Keynes and the slump

Much recent comment has assumed John Maynard Keynes had an answer to the slump which politicians ignored. He did not. He brilliantly tore apart the argument of those economists who claimed it would solve itself if wages were to fall. But his own proposal could not have ended it. For instance, a call that he backed from former British prime minister Lloyd George for public works could not have shaved more than 11 percent off the 100 percent growth in unemployment between 1930 and 1933.58

Every proposal Keynes made, notes his biographer Skidelsky, was tailored to take “into account the psychology of the business community. In practice he was very cautious indeed”.59 Thus a series of articles Keynes wrote for the Times in 1937 suggested that Britain was approaching boom conditions, even though unemployment remained at 12 percent. He was only too aware that capitalists would shy away from any policy which seemed likely to damage profits in the short term. And so, in practice, he avoided recommendations which might frighten them.

Glyn and Howell have argued that to provide the three million jobs needed to restore full employment at the deepest point of the slump would have required an increase in government spending of some 56 percent.60 Such an increase was not possible in Britain using the “gradualist” methods acceptable to Keynes, since it would have led directly to a flight of capital abroad, a rise in imports, a balance of payments deficit and a steep rise in interest rates.61 Carrying it through would have required “the transformation of the British economy into a largely state controlled, if not planned, economic system”.62 So, when government expenditure did start to grow and cut unemployment, it was, according to Eichengreen, “due more to Mr Hitler than Mr Keynes”, with growth by 5 percent in the proportion of GNP going into arms, creating some 1.5 million jobs by 1938.63 A successful Keynes-type policy in the US “would have had to approach the size of government expenditures during the Second World War”.64

In his General Theory Keynes hinted at the failings of capitalism being too deep for merely monetary and fiscal measures to deal with, advancing his own version of falling profit rates (the “declining marginal efficiency of capital”) and saw radical action with the “socialisation of investment” as the only effective counter-slump measure. But he never tried seriously to advance this solution—since under normal peacetime circumstances socialisation of investment is not possible without taking control of capital itself away from the capitalists.

The comparison with the present

The immediately precipitating factors of the present crisis have not been exactly the same as those of the late 1920s. The crisis of the 1930s did not begin as a freezing up of bank lending (a “credit crunch”) but as a crisis in industry, exacerbated by excessive lending in the last phase of the boom, but not directly caused by it. The crisis was a year old before it really hit the banking sector. These differences, however, conceal remarkable underlying similarities.

In both cases capital was faced with a rate of profit lower than two or three decades earlier. In both cases it had succeeded in the pre-crisis years in reducing the share of wages to national income and preventing a collapse of profitability. In both cases this had been sufficient to produce a certain, although rapidly fluctuating, level of productive investment but not on a sufficient scale to absorb all the surplus value produced in previous rounds of production. In both cases the gap between saving and investment that would otherwise have led to recessionary pressures had been filled by unproductive investment and speculative spending, although taking different forms. In both cases a point was inevitably reached where the speculative elements involved in the boom could not be sustained and its underlying weaknesses suddenly came to the fore with devastating effect. In both cases the internationalisation of finance in the previous years—with the US lending to repair the damage to war-torn Europe in the 1920s and with the East Asian and oil states lending to the US in the early and mid-2000s—meant that the crisis became a world crisis.

There are, however, much more significant differences between the situation at the beginning of the present crisis and that in 1929.

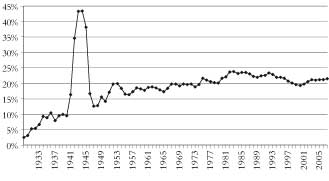

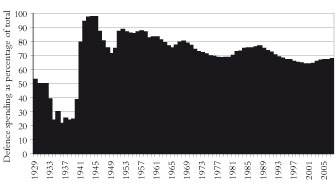

First, state expenditure has for nearly 70 years been central to the system in a way in which it was not in 1929. In that year federal government expenditures represented only 2.5 per cent of GNP;65 in 2007 federal expenditure was around 20 percent of GNP. And the speed and vigour with which the government has moved to intervene in the economy has been much greater this time. The Hoover administration (March 1929-February 1933) did make a few moves aimed at bolstering the economy, so that state spending rose slightly in 1930, and federal money was used to bail out some banks and rail companies through the Reconstruction Finance Corporation in 1932. But the moves were very limited in scope—and the state could still act in ways that could only have exacerbated the crisis in 1931 and 1932. The Fed increased interest rates to banks (a move which Friedman and the monetarists see as turning the recession into a slump) and the government raised taxes (a move which Keynesians argue made the crisis worse). It was not until after the inauguration of the Roosevelt administration in March 1933 that there was a decisive increase in government expenditure. But even then the high point for total federal government spending in 1936 was only just over 9 percent of national output—and in it 1937 began to decline. By contrast, the cost of bailouts pushed through by the Bush government in its dying days, just as the credit crunch began to turn into a recession, could amount to an extra 10 percent of GNP.

Figure 1: Net federal expenditure as a percentage of GDP

Source: Éric Tymoigne, “Minsky and Economic Policy: ‘Keynesianism’ All Over Again?”, Levy Economics Institute, working paper

Figure 2: Composition of federal expenditure

Source: Éric Tymoigne, “Minsky and Economic Policy: ‘Keynesianism’ All Over Again?”, Levy Economics Institute, working paper

The increased importance of state expenditures—and the willingness of central banks and government to spend rapidly in trying to cope with the crisis—means there is a base level of demand in the economy which provides a floor below which the economy will not sink, which was not the case in the early 1930s. In this military expenditure, at $800 billion twice the level in current dollars of 2001, plays a particularly important role guaranteeing markets to a core group of very important corporations. Such spending can clearly serve to mitigate the impact of the crisis, even if the employment effect per dollar of military spending is much less today than, say, at the height of the Korean War in 1951.66

But there is an important second difference that operates in the opposite direction. The major financial and industrial corporations operate on a much greater scale than in the inter-war years and therefore the strain on governments of bailing them out is disproportionately larger. The banking crises of the early 1930s in the US was a crisis of a mass of small and medium banks—”Very big banks did not often become insolvent and fail, even in periods of widespread bank failures”67—while in Britain there was no bank crisis at all. This time we have seen a crisis of many of the biggest banks in most major economies. Within a day of Lehman Brothers going bust on 15 September, banks such as HBOS in Britain, Fortis in the Benelux countries, Hypo Real Estate in Germany and the Icelandic banks were all in trouble. From there the crisis spread to affect other major banks and the “shadow banking system” of hedge funds, derivatives and so on. The most recent estimate of the total losses so far, from the Bank of England, amounts to $2,800 billion.68 The banking system can only perform its normal function of providing credit for the rest of capitalism if the huge holes in its balance sheets are filled up with real value.69 So long as this does not happen then not only will there be a recession due to an end of the lending that kept the consumer and housing booms going in the US, Britain and elsewhere, but it will be massively intensified by the inability of many industrial and commercial firms to keep functioning. For once Martin Wolf of the Financial Times has described what is happening accurately:

The leverage machine is operating in reverse and, as it generated fictitious profits on the way up, so it takes those profits away on the way down. As unwinding continues, highly indebted consumers cut back, corporations retrench and unemployment soars.70

But restoring the balance sheets of the banks can only be done by eventually extracting real value from elsewhere in the economy—either from other profitable bits of the system or by cutting into the living standards of those who work for it in ways that themselves can have a recessionary impact. It might just be possible for a state with an economy as big as that of the US (still, despite its relative decline, the world’s biggest manufacturing economy and by far the biggest force in the global financial system) to use its resources to damp down the process and prevent recession turning into cumulative collapse. But it is going to be much harder for weaker states with smaller economies and proportionately bigger debt overhangs.

The problems facing Iceland, Hungary and Ukraine are an indication of this. Their governments—and the IMF which is supposedly helping them—have turned to measures of a distinctively non-Keynesian sort, cutting public expenditure and raising interest rates. Other countries with potential problems include Estonia, Latvia, Bulgaria, Romania, Croatia, Pakistan and Indonesia. We could well see multiple examples of the sort of devastating crisis that hit Argentina at the end of 2001, causing political turmoil.

Meanwhile, the experience of Japan in the 1990s provides a warning as to the limits of what government action can achieve even in the biggest economies.

The Japanese crisis of the 1990s

Japan was regarded as the world’s “second economic superpower” when it entered into crisis. Its average growth rate through the 1980s had been 4.2 percent, as against 2.7 percent for the US and 1.9 percent for West Germany; its investment in manufacturing equipment was more than twice that of the US. 71 That the future lay with Japan was the near universal conclusion of media commentators. A US congressional committee forecast in 1992 that Japan would overtake the US by the year 2000. “After Japan” became the slogan of European and North American industrialists trying to motivate their workforces to greater feats of

productivity.

The crisis meant the growth turned to stagnation which, interspersed by brief recession and by even briefer spells of positive growth, lasted for a decade and a half. By 2007 Japan’s economy was only a third of the size of the US’s (and the European Union’s)72 as against estimates of 60 percent in 1992.73

The blame for what happened is usually ascribed to faults in the running of its financial system—either due to financial markets not being “free” enough in the 1980s (the argument of neoliberals) or due to inappropriate action by the central banks once the crisis had started.

Yet all the elements of the Marxist account of the crisis are to be found in the Japanese case. Japan from the 1950s to the late 1980s had a rapidly rising ratio of capital to workers—the ratio grew four times as fast as that in the US in the 1980s.74 This led, as Marx would have predicted, to downward pressures on the rate of profit. It fell by about three quarters between the end of the 1960s and the end of the 1980s.

Table 1: Japanese profit rate

Source: Robert Brenner, The Economics of Global Turbulence

| Period | Manufacturing | Non-financial corporate |

|---|---|---|

| 1960-1969 | 36.2% | 25.4% |

| 1970-1979 | 24.5% | 20.5% |

| 1980-1990 | 24.9% | 16.7% |

| 1991-2000 | 14.5% | 10.8% |

Table 2: Return on investment in Japan

Source: Alexander, 1998

| Year | Return on gross non-residential stock |

|---|---|

| 1960 | 28.3% |

| 1970 | 18.0% |

| 1980 | 7.8% |

| 1990 | 3.9% |

The decline had seemed manageable until the end of the 1980s. In the Japanese version of capitalism there was a high level of state direction of investment, and banks guaranteed investment funds to keiretsu industrial combines without much attention to profit rates. This had ensured that so long as there was a mass of profit available for further investment, it would be used. Whereas the US, for example, invested just 21 percent of its GDP in the 1980s, Japan invested 31 percent.75 But such high investment could only be sustained by holding down the consumption of the mass of the people. Partly this was done by holding back real wages, partly through providing minimal state provision for sickness and pensions, forcing people to save.

As one analyst noted in 1988, “Real wages in Japan are still at most only about 60 percent of real wages in the US, and Japanese workers have to save massively to cope with the huge proportion of their lifetime earnings which is absorbed by such things as housing, education, old age and healthcare”.76

This low level of real wages restricted the domestic market for the new goods Japanese industry was turning out at an ever-increasing speed. Even with high levels of investment, consumer demand could not absorb the rest: “Growing labour productivity in the consumer goods branches of the machinery industries (eg motor cars and audio-visual equipment) had to find outlets in export markets if the Japanese working class’s limited buying power was not to interrupt accumulation”.77

But then in the late 1980s both domestic investment and exports came under pressure. Gillian Tett of the Financial Times writes in her journalistic account of the crisis that “by the late 1980s” it was “increasingly difficult…to invest…productively”;78 Burkett and Hart-Landberg tell of “overproduction of surplus value relative to productive and privately profitable investment opportunities”.79

The long-term fall in the rate of profit was finally making an impact. And as this was happening the Reagan government made it more difficult for Japan to export on the old scale by twisting its arm to increase the international value of the Japanese yen—and therefore the price of Japanese goods to US consumers—with the Plaza agreement of 1985. It was in response to this situation that the bubble economy emerged.

“To compensate the corporate sector for the squeeze of the exchange rate, the ministry [of finance] encouraged the banks vastly to increase their lending”.80 The increased bank lending found its way into speculation on a massive scale. “The explosion of liquidity helped set off an upward spiral of real estate values, long used as collateral by the big companies, which then justified inflated stock values”.81 Property values soared and the stock exchange rose until the net worth of Japanese companies was said to be greater than that of the US companies, despite the still considerably greater size of the US economy. So long as the bubble lasted the Japanese economy continued to grow, and even after the bubble had started deflating (with the Tokyo stock exchange’s Nikkei index falling 40 percent in 1990) bank lending enabled the economy to keep expanding, although now at only about 1 percent a year, through the 1990-92 recession in the US and Western Europe.

But the banks themselves were increasingly in trouble. They had made loans for land and share purchases that could not be repaid now that these things had collapsed in price. By 1995 the government was having to use public money to rescue two banks. It then briefly put its faith in “big bang reforms” to make the Tokyo market “free, fair and global”, only to see a few months of recovery give way to recession and a succession of further bank crises—with banks writing off a total of around 71 trillion yen (over $500 billion) in bad loans. By the early 2000s the total sum owed by businesses in trouble or actually bankrupt was estimated to be 80 to 100 trillion yen ($600 to $750 billion) by the US government, and 111 trillion yen (nearly $840 billion) by the IMF.82

The role of the financial system in producing the bubble and then the long drawn out banking crisis has led most commentators on the Japanese crisis to locate it in faults in that system. The problem, the neoliberals claim, was that the close ties between those running the state, the banking system and industry meant there was not the scrutiny about what the banks were up to which a truly competitive economy would have provided.83 When the Clinton administration’s treasury secretary, Larry Summers, visited Tokyo in 1998 he contrasted Japan with “a financially healthy US banking system”.84 As an explanation it fails because very similar bubbles have happened in economies like the US, which supposedly fulfil all the norms of “competitiveness”. It is difficult to see any fundamental difference between the Japanese bubble of the late 1980s and the US housing bubble of the mid-2000s.

But there is no reason to believe that the banking crisis was the ultimate cause of Japanese stagnation. The fall in the rate of profit led to a fall in productive investment, although not anything like a complete collapse. The neoclassical economists Fumio Hayashi and Edward C Prescott argue that firms that wanted to invest could still do so but recognised that “those projects” that were funded “on average receive a low rate of return”.85 In such a situation restructuring the banking system, whether through allowing the crisis to deepen, as the neoliberals wanted, or gradually, as those of a more Keynesian persuasion suggested, would not solve the crisis. Paul Krugman made the point:

The striking thing about discussion of structural reform is that when one poses the question “How will this increase demand?”—as opposed to supply—the answers are actually quite vague. I at least am far from sure that the kinds of structural reform being urged on Japan will increase demand at all, and see no reason to believe that even radical reform would be enough to jolt the economy out of its current trap.86

Krugman offered a panacea of his own—pumping still more money into the banks. But even if this could have worked it would have meant a new bubble, with the same problems re-emerging in the not too distant future. The reason was that the trap lay in something Krugman, as a supporter of capitalism, albeit a sometimes critical one, could not grasp. The origins of the crisis lay outside the banking system, in the capitalist system as a whole. The low rate of profit both kept down investment and precluded capitalists voluntarily allowing wages to rise. But that in turn prevented the domestic economy from being able to absorb all of the increased output. A new massive round of accumulation could have absorbed it, but for that profitability would have had to have been much higher than it was.

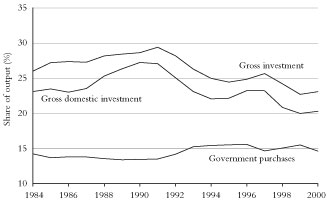

The state did turn to some Keynesian type solutions, with a big programme of public works construction (bridges, airports, roads, etc), which according to one estimate raised the government’s share of output from an average of 13.7 percent in 1984-90 to 15.2 percent in 1994-2000.87 Gavan McCormack claims that, with the onset of chronic recession after the bubble burst at the beginning of the 1990s, the government turned to ever larger—and decreasingly effective—Keynesian deficits:

Japan’s public works sector has grown to be three times the size of that of Britain, the US or Germany, employing 7 million people, or 10 percent of the workforce, and spending between 40 and 50 trillion yen a year—around $350 billion, 8 percent of GDP or two to three times that of other industrial countries.88

In fact, it you take arms spending into account, then the US and Japanese states must be undertaking similar levels of “non-productive” expenditure. But it is not enough to fill the gap created in Japan by the limited stimulus to investment from the rate of profit, as figure 3 shows. The economy did not collapse in the 1990s in the way that the US and German economies did in the early 1930s.89 The state still seemed able to stop that. But it could not lift the economy back to its old growth path, whether by monetarist means, Keynesian means or a combination of the two.90 Sections of Japanese capital believed they could escape from this trap by investing abroad—as the gap between gross investment and gross domestic investment shows. Japan did manage to achieve some limited economic growth by exporting capital goods and intermediate products to China, which then used them to produce consumer goods for the US. But this has not provided an answer for the great bulk of Japanese capital which is doing its utmost to try to raise the rate of profit through raising the rate of exploitation, even though it can only reduce domestic demand still further and deepen its problems. And now Japan has been drawn into the recessionary whirlpool created by the global financial crisis.

Figure 3: Japanese government purchases and investment

Source: Hayashi and Prescott, 2002

The Japanese experience, like that of the Roosevelt New Deal, seems to indicate that the maximum that state intervention, short of a massive encroachment on private capital, may be able to achieve is to prevent a complete collapse, but it cannot by itself overcome the fundamental imbalance caused by profit rates and restore the old dynamism. If this is so we are in for a very serious crisis. A decade and a half of paralysis for the Japanese economy did not mean devastation for the rest of the world, even if it did play a role in precipitating the crisis that hit the rest of East and South East Asia, Russia and Latin America in 1997. The effect of a decade and half of paralysis in the US would be felt everywhere, and not only in economic terms, since US-based capital would use the might of the US state and its still dominant role in the world financial system to offload the costs of the crisis on to weaker parts of the system.

Conclusion

There is a natural desire for people to want to know exactly how serious this crisis is going to be. But this is one thing Marxists cannot predict. Writing to Frederick Engels in 1873, Marx lamented his incapacity to work out in advance how crises were going to develop:

I have been telling [Samuel] Moore about a problem with which I have been racking my brains for some time now. However, he thinks it is insoluble, at least pro tempore, because of the many factors involved, factors which for the most part have yet to be discovered. The problem is this: you know about those graphs in which the movements of prices, discount rates, etc, etc, over the year, etc, are shown in rising and fall-ing zigzags. I have variously attempted to analyse crises by calculating these ups and downs as irregular curves and I believed (and still believe it would be possible if the material were sufficiently studied) that I might be able to determine mathematically the principal laws governing crises. As I said, Moore thinks it cannot be done at present and I have resolved to give it up for the time being.91

It is an incapacity that still afflicts Marxists today. When banks don’t know how big their debts are we can hardly claim special knowledge. For the moment all we can do is extend the “bail out” metaphor: the pails being used are bigger than ever in the past but the pool of debt they have to dispose of is also much deeper. The panicking politicians and terrified capitalists doing the bailing out can hardly avoid clashing with each other as they try to cope with problems they never thought they would face. The point has been reached now where some of capitalism’s strongest supporters, frustrated by the banks’ inability to provide desperately needed credit to industrial and commercial firms, are muttering about the possibility of complete state takeovers of whole national banking systems. Others are worried about what happens if at some point the banks suddenly release into the “real economy” the huge sums they have been fed by states, creating massive inflationary pressures and “a huge recession” later rather than sooner.92 Such is the confusion among those committed to defending the system.

Revolutionary socialists today should not be mirroring such confusion by pontificating on the degree of damage capitalism has done to itself, on whether we are in 1929, 1992 or whenever. The central thing we need to understand is that the crisis is not simply a fault of a lack of financial regulation or bankers’ greed, but is systemic, and that the major units of capital have become too big for the system to emerge from crisis through blind workings of the market mechanism. That is why states have had to intervene even if their intervention creates new problems and, with them, political and ideological turmoil. We should taking advantage of the turmoil to put across forcefully socialist arguments while seeking to be at the centre of the manifold forms of resistance as our rulers try to make the mass of people pay for the crisis. We do not have a crystal ball into the future, but we can see all too clearly what is happening now and what our responsibilities are. As James Connolly once put it, “The only true prophets are those who carve out the future.”

Notes

1: Quoted in Parker, 2007, p x.

2: Quoted in Parker, 2007, p95.

3: Quoted in Parker, 2007, p95.

4: Kindleberger, 1973, p117. See also the figures for industrial production month by month in Robbins, 1934, p210, table eight. The US National Bureau of Economic Research dates the beginning of the recession as August 1929, ie two months before the crash-Parker, 2007, p9.

5: Hansen, 1971, p81.

6: Kindleberger, 1973, p117.

7: Eichengreen, 1992, pp213-239.

8: Friedman and Schwartz, 1965, p8.

9: Flamant and Singer-Kerel, 1970, pp40, 47, 53.

10: Friedman and Schwartz, 1965, p21.

11: Hart and Mehrling, 1995, p56.

12: Hart and Mehrling, 1995, p58.

13: Kindleberger, 1973, p233.

14: Kindleberger, 1973, p232.

15: Kindleberger, 1973, p272.

16: There can be no certain way of knowing whether that would have been the outcome even without the government’s measures.

17: Galbraith, 1993, p65.

18: See, for instance, Parker, 2007, p14.

19: See the two volumes of interviews by Parker (2007).

20: For a more detailed explanation, see Harman 2007.

21: See Grossman, 1992; Kuhn, 2007.

22: See the calculations in Gillman, 1956; Mage, 1963; Dumenil and Levy, 1993, p254; Corey, 1935.

23: Gillman, 1956, p58; Mage, 1963, p208; Dumenil and Levy, 1993, p248, figure 14.2.

24: Gillman has the rate of exploitation falling from 69 percent in 1880 to 50 percent in 1900 to 29 percent in 1919 and 1923, but then rising again to 32 percent in 1927. Mage’s figures are different, but the trend is the same. He has it at 10.84 percent in 1900, and 12.97 percent in 1903. Thereafter it falls to 12.03 percent in 1911 and to 6.48 percent in 1919. But then it rises again to 7.19 percent in 1923 and 7.96 percent in 1928. By contrast, Corey has it falling from 1923 to 1928 and then rising in 1929.

25: Corey, 1935, pp181-183.

26: Berstein, 1987, p172.

27: Steindl, 1976, p166.

28: Gordon, 2004. Corey also implies big growth in productive investment, with figures showing capital investment rising 50 percent between 1923 and 1929 and fixed capital of over 30 percent. Corey, 1935, pp114, 115, 125.

29: This seems to be true of Corey’s figures, which include “real estate, buildings and equipment”.

30: Hansen, 1971, p290-291.

31: Gordon, 2004, p17. Investment “excluding dwellings” was only “high enough” to raise the capital stock…a little faster that the employed population”, according to Brown and Browne, 1968, pp250-251.

32: Editorial in Annalist, 16 July 1926, p68, quoted by Corey, 1935.

33: Article in Annalist, 28 July 1933, p115, quoted by Corey, 1935.

34: Hansen, 1971, p296.

35: Corey, 1935, p157.

36: Corey, 1935, p170.

37: Eichengreen and Mitchener, 2003.

38: Gordon, 2004, p16.

39: Gordon, 2004, p16.

40: Hansen, 1971.

41: Quoted in Temin, 1976, p32-33.

42: Figures given in Robbins, 1934.

43: For details, see Wilmarth,2004, pp92-95.

44: On the volatility of the debt based consumer goods market, see Martha Olney summarised in Temin, 1996, p310.

45: The disruption of the German economy after 1918, with loss of territory, especially the industrially important Alsace-Lorraine, and the inflation of 1923, must make any pre- and post-war comparisons difficult.

46: Balderston, 1985, p406.

47: Balderston, 1985, p400.

48: Balderston, 1985, p406.

49: Balderston, 1985, p410.

50: Balderston, 1985, p415.

51: Balderston, 1985, pp 395, 396.

52: For profitability before 1914, Arnold and McCartney, 2003. For profitabality before and after the First World War, see Brown and Browne, 1968, pp412, 414, tables 137, 138.

53: See figure 13.1 in Hatton, 2004, p348.

54: Another important subsidiary factor came into play. The recessions in the US and Germany led to a massive worldwide fall in food and raw material prices. This was devastating for their farmers, who were still a significant section of the population and for banks that had lent to them. By contrast in Britain, where the agricultural population was already very small, the fall in food prices enabled employed workers to enjoy rising living standards and to provide a market by the mid-1930s for a range of new light engineering and electrical industries.

55: Preobrazhensky, 1985, p35. He did not, however, integrate the fall in the rate of profit into his analysis.

56: Bernanke, 2000, p46.

57: Even railway firms that were forced to go into bankruptcy proceedings “were almost never liquidated”-Mason and Schiffman, 2004.

58: Estimate given in Middleton, 1985, pp176-177.

59: Skidelsky, 1994, p605.

60: Quoted in Middleton, 1985, pp176-177.

61: These points are well made in Pilling, 1986, pp50-51.

62: Arndt, quoted in Middleton, 1985, p179.

63: Eichengreen, 2004, p337.

64: Norman quoted by Temin, 1976, p6.

65: The free-market website USgovernmentspending.com gives the figure of 3.7 percent. In both years expenditure by US states is in addition to the federal expenditure figures-adding 8.4 percent of GNP in 1929 and 16 percent in 2007.

66: This is because the speed of technical progress in arms production has been much more rapid than in most of the rest of the economy. Put crudely, manufacturing missiles in 2008 is much less labour intensive than manufacturing tanks was in 1951. The workforce at the giant Boeing plant in Seattle, for instance, is less than half the size it used to be.

67: Kaufman, 2004, p156.

68: Bank of England Stability Report, October 2008, quoted in the Guardian, 28 October 2008. Various other estimates, sometimes lower, exist from, for instance, the IMF.

69: In an illuminating passage in volume three of Capital, Marx argues that bank profits are claims on value produced elsewhere in the system: “All this paper actually represents nothing more than accumulated claims, or legal titles, to future production whose money or capital value represents either no capital at all…or is regulated independently of the value of real capital which it represents… And by accumulation of money-capital nothing more, in the main, is connoted than an accumulation of these claims on production”-Marx, 1962, p458. What happened through the early and mid-2000s was that the banks assumed that these claims were themselves real value and entered them in the positive side of their balance sheets. Now, faced with the decline in the mortgage and property markets, they have to try to cash them in if they are not going to go bust-and find they cannot. This is what “deleveraging” is about, and why the survival of banks depends on finance from states.

70: Martin Wolf, “A Week Of Living Perilously”, Financial Times, 22 November 2008.

71: Figures given in Kossis, 1992, p119.

72: World Development Indicators database, World Bank, July 2007.

73: Kossis, 1992.

74: Scarpetta, Bassanini, Pilat and Schreyer, 2000.

75: Alexander, 1998, figure 2.

76: Stevens, 1988, p77.

77: Stevens, 1988, pp76-77.

78: Tett, 2004, p36.

79: Burkett and Hart-Landberg, 2000, p50.

80: Wolferen, 1993.

81: [reference]

82: McCormack, 2002; Gillian Tett quotes estimates for the cost of clearing up bad loans of $200 billion and $400 billion, with one suggested figure of $1.2 trillion. Tett, 2004, p281.

83: Regrettably, some left wing commentators with a quite justified distaste for the Japanese ruling class also imply that if it had been more “Western” in its approach to competitiveness, things would have turned out differently.

84: Quoted in Tett, 2004, p121.

85: Hayashi and Prescott, 2002.

86: Krugman, 1998.

87: Hayashi and Prescott, 2002.

88: McCormack, 2002.

89: Hayashi and Prescott, 2002.

90: The failure of successive governments and Bank of Japan initiatives is spelt out very well in Graham Turner’s The Credit Crunch (2008), even though he himself seemed to believe at the time of writing there was a magic bullet which could have been used to stop the crisis if used at the right moment.

91: Quoted in Carchedi, 2008.

92: This is essentially the fear expressed in Wolfgang Muenchau, “Double Jeopardy For Financial Policy Makers”, Financial Times, 24 November 2008.

References

Alexander, Arthur, 1998, Japan in the context of Asia (Johns Hopkins University).

Arnold, Tony, and Sean McCartney, 2003, “National Income Accounting and Sectoral Rates of Return on UK Risk-Bearing Capital, 1855-1914”, Essex University, school of accounting, finance and management, working paper, www.essex.ac.uk/AFM/Research/working_papers/WP03-10.pdf November 2003

Balderston, Theo, 1985, “The Beginning of the Depression in Germany 1927-30”, Economic History Review, volume 36, number 3.

Bernanke, Ben, 2000, Essays on the Great Depression (Princeton).

Berstein, Michael A, 1987, The Great Depression (Cambridge University).

Brown, Ernest Henry Phelps, and Margaret H Browne, 1968, A Century of Pay (Macmillan).

Burkett, Paul, and Martin Hart-Landberg, 2000, Development, Crisis and Class Struggle (Palgrave Macmillan).

Carchedi, Gugliemo, 2008, “Dialectics and Temporality”, Science and Society, volume 72, number 4.

Corey, Lewis, 1935, The Decline of American Capitalism (Bodley Head), www.marxists.org/archive/corey/1934/decline/

Dumenil, Gerard, and Dominique Levy, 1993, The Economics of the Profit Rate (Edward Elgar).

Eichengreen, Barry, 1992, “The Origins and Nature of the Great Slump Revisited”, Economic History Review, new series, volume 45, number 2.

Eichengreen, Barry, 2004, “The British Economy Between the Wars”, in Floud and Johnson, 2004.

Eichengreen, Barry, and Kris Mitchener, 2003, “The Great Depression as a Credit Boom Gone Wrong”, BIS Working Papers, 137, www.bis.org/publ/work137.pdf

Flamant, Maurice, and Jeanne Singer-Kerel, 1970, Modern Economic Crises (Barrie & Jenkins).

Floud, Roderick, and Paul Johnson (eds), 2004, The Cambridge Economic History of Modern Britain, volume two (Cambridge University).

Friedman, Milton, and Anna Schwartz, 1965, The Great Contraction 1929–33 (Princeton).

Galbraith, John Kenneth, 1993, American Capitalism (Transaction).

Gillman, Joseph, 1956, The Falling Rate of Profit (Dennis Dobson).

Gordon, Robert J, 2004, “The 1920s and the 1990s in Mutual Reflection”, paper presented to economic history conference, “Understanding the 1990s: The Long-term Perspective”, Duke University, 26-27 March 2004, www.unc.edu/depts/econ/seminars/Gordon_revised.pdf

Grossman, Henryk, 1992 [1929], Law of Accumulation and Breakdown of the Capitalist System (Pluto),

www.marxists.org/archive/grossman/1929/breakdown/

Gup, Benton E (ed), 2004, Too Big to Fail (Praeger).

Hansen, Alvin H, 1971, Full Recovery or Economic Stagnation (New York).

Harman, Chris, 2007, “The Rate of Profit and the World Today”, International Socialism 115 (summer 2007), www.isj.org.uk/?id=340

Hatton, Timothy J, 2004, “Unemployment and the Labour Market 1870-1939”, in Floud and Johnson, 2004, http://econrsss.anu.edu.au/Staff/hatton/pdf/FandJUnemp.pdf

Hart, Albert G, and Perry Mehrling, 1995, Debt, Crisis and Recovery (ME Sharpe).

Hayashi, Fumio, and Edward C Prescott, 2002, “The 1990s in Japan: A Lost Decade”, Review of Economic Dynamics, volume 5, issue 1, www.minneapolisfed.org/research/WP/WP607.pdf

Kaufman, George, 2004, “Too Big to Fail in US Banking”, in Gup, 2004.

Kindleberger, Charles P, 1973, The World in Depression 1929–39 (Allen Lane).

Kossis, Costas, 1992, “A Miracle Without End”, International Socialism 54 (spring 1992).

Krugman, Paul, 1998, “Japan’s Trap”, http://web.mit.edu/krugman/www/japtrap.html

Kuhn, Rick, 2007, Henryk Grossman and the Recovery of Marxism (University of Illinois).

Mage, Shane, 1963, “The ‘Law of the Falling Rate of Profit’, its Place in the Marxian Theoretical System and its Relevance for the US Economy”, PhD thesis, Columbia University, released through University Microfilms, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Marx, Karl, 1962 [1894], Capital, volume three (Moscow), www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1894-c3/

Mason, Joseph R, and Daniel A Schiffman, 2004, “Too Big to Fail, Government Bailouts and Managerial Incentives”, in Gup, 2004.

McCormack, Gavan, 2002, “Breaking Japan’s Iron Triangle”, New Left Review 13 (January_February 2002).

Middleton, Roger, 1985, Towards the Managed Economy (Routledge).

Parker, Randall E, 2007, Economics of the Great Depression (Edward Elgar).

Pilling, Geoffrey, 1986, The Crisis of Keynesian Economics (Barnes & Nobel).

Preobrazhensky, Evgeny, 1985 [1931], The Decline of Capitalism (ME Sharpe).

Robbins, Lionel, 1934, The Great Depression (Macmillan).

Scarpetta, Stefano, Andrea Bassanini, Dirk Pilat and Paul Schreyer, 2000, “Economic Growth in the OECD Area”, OECD economics department working papers, number 248, www.sourceoecd.org/10.1787/843888182178

Skidelsky, Robert, 1994, John Maynard Keynes, volume 2 (Papermac).

Steindl, Josef, 1976, Maturity and Stagnation in American Capitalism (Monthly Review).

Stevens, Rod, 1988, “The High Yen Crisis in Japan”, Capital and Class 34 (spring 1988).

Temin, Peter, 1976, Did Monetary Forces Cause the Great Depression (Norton).

Temin, Peter, 1996, “The Great Depression”, in Stanley L Engerman and Robert E Gallman (eds), The Cambridge Economic History of the United States, volume two, the 20th century (Cambridge University).

Tett, Gillian, 2004, Saving the Sun (Random House).

Turner, Graham, 2008, The Credit Crunch (Pluto).

Wilmarth, Arthur E, 2004, “Does Financial Liberalization Increase the Likelihood of a Systemic Banking Crisis”, in Gup, 2004.

Wolferen, Karel van, 1993, “Japan in the Age of Uncertainty”, New Left Review, first series, 200 (July-August 1993).