On 8 August 2019 the Brazilian president, Jair Bolsonaro, hailed a former torturer—Brilhante Ustra—as a “national hero”.1 This gesture may be very enlightening, explaining who Bolsonaro is: a genealogy of his own roots in the Brazilian Army would connect him to this torturer because he was in a regiment commanded by Ustra.2 This episode was not a one-off; on 17 April 2016, during the session that impeached the then Workers’ Party (PT) president Dilma Rousseff, Bolsonaro used his nationally televised vote to publicly hail the torturer.3 As torture is a crime—an imprescriptible crime—in the Brazilian Constitution (article 5, XLII), and apology for crime is also a crime (Penal Code, article 287), it was very strange that Bolsonaro went unpunished—a hint at the limitations of Brazil’s parliamentary and judicial systems4 and an indication of the limits of our transition from the military regime in 1985-88.5

During the impeachment process, far-right movements began to grow. In 2017, Michel Temer’s government deepened the political and economic crises. Politicians from the two main centre-right parties, the Brazilian Social Democratic Party, or PSDB (the party of Aécio Neves, who ran against Dilma in 2014), and the Brazilian Democratic Movement Party, or PMDB (the party of the head of the Congress during Dilma’s impeachment process, Eduardo Cunha, and Temer himself) were also involved in corruption charges. In fact, the process included all parties that were in government since 1991, including former PT president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, in jail since April 2018. Those events certainly strengthened Bolsonaro’s electoral chances and the far right prospered in this environment of crisis in a process that remains to be understood. The electoral environment in 2018 also included random factors that might have influenced the outcome. For example, Bolsonaro was stabbed in the stomach during an election campaign rally on 6 September 2018. The first round of voting was in 7 October 2018.

Bolsonaro, a former army captain elected city councillor in Rio de Janeiro in 1988, has been a member of the Brazilian parliament since 1991.6 He won both rounds in the presidential election and was elected president on 28 October 2018 with 55.13 percent of the vote.7 The electoral process took place in an economic, social and political context shaped by the 2014 economic crisis and the increasing political and social problems that deepened during Dilma’s impeachment process (2015-16) and Temer’s government (2016-18). It is a context of social deterioration due to measures of social regression and political stalemate.8

But Bolsonaro is also a symptom of much earlier problems in Brazilian history. His rise is a puzzle to be investigated by researchers of various fields. It has roots in the long colonial history of Brazil—from 1500 to 1822, an independence negotiated within the Portuguese royal family that resulted in the first King of Brazil becoming a successor to the Portuguese throne, a lengthy period of slavery that ended only in 1888, a republic created by a military coup d’état, two long lasting dictatorships during the 20th century (1930-45 and 1964-85) and a negotiated transition from the last military regime. Those political and social arrangements led to a very specific variety of capitalism. They produced a very unequal society and, as a consequence, an economy caught within the “historical trap” that is underdevelopment.9

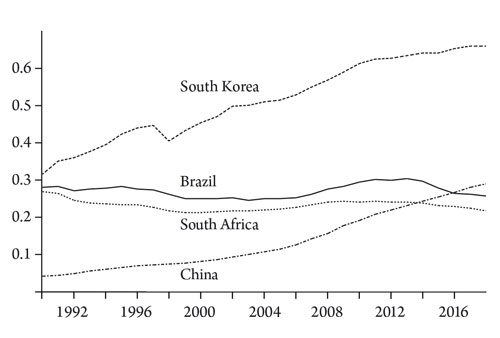

Bolsonaro’s rise also has roots in more recent Brazilian history, especially in the limitations of policies towards economic development and social equality that were unable to overcome underdevelopment. Figure 1 shows how Brazilian GDP per capita since 1990 has oscillated at around 30 percent of that of the United States, with a slight falling behind after 2013. Figure 1 also shows how the Brazilian trajectory differs from those of South Korea and China, two economies which are catching up, and how its trajectory is similar to that of South Africa.

Figure 1: Income gap—GDP per capita of selected countries compared to that of the United States (1990-2018)

Source: World Bank, 2019. Go to http://data.worldbank.org/indicator

Bolsonaro’s government is only nine months old. But it already provides enough clues as to its specific nature as the core of a political arrangement for an uncontrolled predatory capitalism. Its political actions and measures seem to have a very clear goal, which is to unleash this predatory side of Brazilian capitalism. To achieve this, institutional changes are important and Bolsonaro has put in place regressive policies everywhere, at national and local levels. Whether or not this nucleus will prosper is the most important issue of Brazilian politics—it depends on the strength and growth of popular mobilisation, on the resilience of our democratic institutions and on the new energies that can be created by the resistance to those regressive measures.

The electoral year in 2018: economic and social conditions

Among the roots of the “underdevelopment trap” there are four vicious cycles. First, inequality blocks the growth of domestic markets, which in turn blocks development; second, reliance on natural resources and relatively backward industries becomes “locked in”; third, the resource base of Brazil may be exploited in a predatory way, “opening room for the predominance of a predatory economic dynamics over an innovative economic dynamics”;10 fourth, a relationship develops between economic slowdowns and political stalemates.11

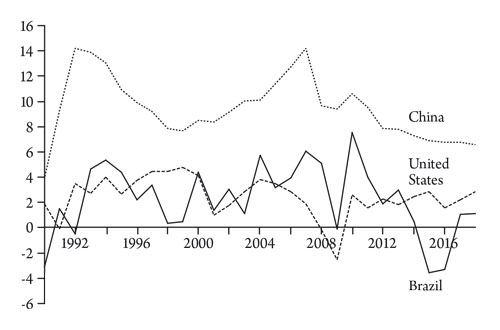

Figure 2 compares GDP growth for Brazil with China and the US. It shows that the elections of 2018 took place in an economic environment shaped by a long downturn: declining rates of GDP growth since 2013, with negative growth rates in 2015 and 2016 and weak growth rates in 2017 and 2018. GDP per capita in 2018 stood at 92 percent of its level in 2013.12

Figure 2: GDP growth (percentage), United States, China and Brazil (1990-2018)

Source: World Bank, 2019. Go to http://data.worldbank.org/indicator

This economic conjuncture is combined with a very specific new political scenario opened up by Dilma’s impeachment where Temer’s government had a clear agenda of regressive social measures and was partially successful in implementing them. Two measures in particular are very important: a long-term policy of austerity (PEC 95, 15 December 2016) and a labour reform law (Law number 13467, 13 July 2017).

This combination led to a deterioration in social conditions.13 Inequality began to grow: between the fourth quarter of 2014 and the second quarter of 2019 the Gini index (a measure of inequality) rose from 60 to 63.14 Poverty increased: from the end of 2014 to the end of 2017, the percentage of the population in poverty grew from 8.38 to 11.8 percent.15 And there was a rise in unemployment between 2014, when the unemployment rate stood in the neighbourhood of

7 percent, to a rate closer to 12 percent in the last quarter of 2018 (these figures do not include informal workers).16 Furthermore, during this period there was a rise in long-term unemployment (persons unemployed for at least two years) from 17.5 percent of the unemployed in the first quarter of 2015 to 24.8 percent in the first quarter of 2019.17

The austerity measures implemented in 2016 have also affected the Brazilian health system. According to an article in the Lancet medical journal, these “will exacerbate chronic underfunding of the SUS [Sistema Único de Saúde, the publically funded healthcare system], leaving a health system that serves the poorest populations with poor quality of care, with worsening health outcomes, financial protection, and inequities”.18

So, this scenario of economic crisis and social deterioration formed the background to the 2018 electoral process. Politically, Temer’s government was involved in corruption charges that affected his party, the PMDB, and those charges fed the political stalemate that persisted during the electoral process. Lula was imprisoned on 7 April 2018 as a result of the anti-corruption Operation Lava-Jato (“Operation Car Wash”), which had clearly become partisan, and which influenced the electoral process since he was later forbidden from being a presidential candidate. The federal judge who imprisoned Lula, Sérgio Moro, later became a minister of Bolsonaro’s government in a move that showed that his position is in conflict with the very basic need for an impartial judicial system.19

In this scenario, Bolsonaro’s campaign grew. The previously mentioned stabbing also softened the attacks from the PSDB—a party competing for votes with him—and gave him excuses not to participate in the debates during the first and second rounds of the election. Bolsonaro’s election opens a new political scenario in Brazil: de-democratisation has become a real threat.20

De-democratisation in Brazil

Democracy, participation and social movements are able to block the institutional preconditions for an uncontrolled predatory capitalism. Therefore, an erosion of those institutions is an important prerequisite for Bolsonaro’s economic project. That is why his government means an intensification of the process of de-democratisation. This process did not start with him, but Bolsonaro is a point of inflexion.

Assuming, as Charles Tilly suggests, that democracy is a continuous process of extending the degree of relationship between the state, via public policy, and a mobilised civil society, the process of de-democratisation will occur whenever this process is reversed through the increasing isolation of state agents from “the main inequalities (gender, ethnicity, race, religion and class) around which citizens organise their daily lives”.21 That is, democracy is reversed whenever the gap between state decisions (public policies) and the representation of civil society widens, compromising both the organisation of society and the very functioning of the state.

This section, a narrative portraying the growing process of “de-democratisation” in Brazil, has three parts. The first briefly describes the participatory infrastructure of 21st century Brazil, the second examines the Emenda Constitucional EC 95/2016 (a Constitutional Amendment) launched by the executive and approved by Congress during Temer’s government (2016-18) and which announces the displacement of the relationship between state and organised civil society due to the austerity policies that affected many social programmes. Finally the third analyses the rhetoric and practice of Jair Bolsonaro (2019- ???) with respect to democracy.

Participation in post-dictatorship Brazil

After the end of the military dictatorship, the new Brazilian Constitution (approved in 1988) provided a major stimulus to the formation of a plural participatory infrastructure that consolidated a rise in social movements in diverse sectors since the late 1970s; a mobilisation that contributed to the end of the authoritarian regime. This long-term process resulted, in the 2000s, in a plural participatory infrastructure. The new Constitution introduced a set of participatory innovations that broke with the monopolistic character of representation in Brazil by linking social policies to the creation of public policy councils and conferences. Those councils and conferences operate simultaneously through social participation and political representation. They configure important socio-state interfaces that stimulate social learning in the formulation and control of public policies.22

These innovations are constitutionally mandatory for various public policies such as health, social assistance and rights for children and teenagers. Over time the use of these councils and conferences has become routine practice in many other policy areas. For many, these spaces offered a promise of political inclusion, as they enabled a more permanent and creative relationship between social and political actors, and they may be related to important gains captured by the statistics of human development indices.

Until now, all Brazilian municipalities have at least one public policy council. According to data from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), there are about 36,000 local councils in Brazil.23 The most common councils are Social Assistance (in 5,527 municipalities), Health (in 5,417), Rights of Children and Teenagers (in 5,084), Education (in 4,403), Environment (in 3,124), Housing (in 2,373), Rights of the Elderly (in 2,373) and Culture (in 1,974).24 As well as councils and conferences, the strength of participation in Brazil can also be gathered by the spread of civil society organisations. By 2016 there were 820,000 “organizações da sociedade civil” (civil society organisations, OSCs) in Brazil.25 OSCs have expanded greatly in recent years, spurred on by state reforms initiated in those years. In spite of divergent interpretations regarding their functions, the data portray a sector that, until recently, had been growing.26

According to Wanderley Guilherme dos Santos, in 2010, 200,700 private organisations, foundations and associations accounted for 52 percent of the total of 556,800 non-profit entities and 5.2 percent of the total 56 million public or private entities, for-profit or otherwise, of the IBGE’s General Register of Companies in the same year. Religious (29 percent), employers and non-trade union (15.5 percent), advocacy (14.7 percent) and social assistance (10.5 percent) organisations comprised 70 percent of the census universe. By region, the total number of entities grew between 2006 and 2008, more than the average of

3.7 percent for Brazil, showing a nationalisation of social participation.27

Added to these socio-state interfaces, there has been a series of protests in Brazil in the past decade that show, at the same time, the vitality and the plurality of the forms of action of civil society. Luciana Tatagiba and Andreia Galvão collected and analysed a set of protests over the years 2011 to 2016 published in the national newspaper Folha de Sao Paulo showing the heterogeneity of actors and demands, many of them linked to the public policies alluded to.28 These data, when analysed in the light of information on councils, conferences and OSCs, confirm a plural pattern of action by social actors in Brazil. The novelty in recent years consists in the fact that this pattern is no longer comprised only of the popular sectors and their daily struggles to widen and democratise the limits of the Brazilian state. It also includes groups that have fought severely against policies in support of sex education in primary and secondary schools, sexual and reproductive rights and the defence of minority rights. Therefore, the protests demonstrate the dissatisfaction of a plurality of social actors, indicating the presence of a “social conflict” that also combines with other forms of action depending on the actors and their action trajectories.29 The social sectors involved are students, homeless people, the landless, indigenous people, women and also representatives of right-wing groups that support an agenda linked to the restoration of traditional values, austerity and anti-corruption. Concerning the aims of the protests, the authors reported demands for a reduction in public transport fares; strikes by civil servants; protests against the construction of hydroelectric dams;30 protests against the 2012 New Forest Code, which threatened the Amazon rainforest; campaigns for agrarian reform and protests against the division of oil royalties and against the privatisation of airports. As mentioned, protests against minority rights, sexual and reproductive rights and abortion, as well as anti-corruption were also registered through the years. But these occurred mainly after 2013.31

Temer’s government

President Temer, the day after he succeded Dilma following her impeachment on 31 August 2016, cancelled most of the special secretariats linked to rights and social protection that were created after 2003 through a Provisional Measure sent to Congress. He extinguished the Ministry of Human Rights, the Ministry for Agrarian Reform, the Special Secretariat on Women’s Rights, the Special Secretariat for Racial Equality and the Ministry of Culture (which was subsequently reinstated).

In addition, he proposed the EC 50, an austerity measure involving limits to public spending to last for 20 years. Temer proposed and approved a labour reform, reducing workers’ rights and institutionalising forms of precarious work (part-time and intermittent work). Also during his government he sent a legal initiative to the National Congress reducing social security protection to all Brazilians, including the most basic protections for the poor, such as a social protection programme that provides a monthly minimum wage paid by the social security system to families living on less than half of that minimum wage. This legal initiative provoked some reaction and failed, but a version of it was resumed by Bolsonaro.

Therefore, we have with the Temer government an important reorganisation of the state and public policies in order to bring them more into line with the interests of the entrepreneurial and financial sectors—the first signs of a process of de-democratisation.

Bolsonaro as a point of inflexion in de-democratisation

“Let’s put an end to all activism in Brazil”.32 This was one campaign promise of the then presidential candidate of Brazil who, shortly after his inauguration, brought in a series of measures in order to fulfill his promise. Bolsonaro has attempted to make social activism “a police case”. This is a very important prerequisite for a new political arrangement.

One very important issue that deserves careful further research is the participation of the military as an institution in Bolsonaro’s government. One leading Brazilian scholar, researching the relationship between the military and politics in Brazil, is very pessimistic, identifying the first signs of regression in this field: “Uma República Tutelada” (A Republic under Tutelage) is the title of his first chapter, discussing the current conjuncture.33

One of the hallmarks of Bolsonaro’s authoritarian practice begins with the publication of Provisional Measures (MP), such as MP 870, which restructured the executive. In this restructuring, the Ministry of Environment lost responsibility for deforestation, climate change and environmental education. The Ministry of Agriculture—a stronghold of ruralistas (conservative landowners politically organised in the Brazilian Congress)—now disputes with INCRA (the National Institute of Colonisation and Agrarian Reform) the responsibility for the demarcation of indigenous lands. The latter, in turn, suspends land expropriations.

In April 2019, through Decree 9,759, the government suspended the operation of almost 90 percent of the “collegiate” organs linked to the federal government. Among these are many of the public policy councils and, consequently, the related conferences. As we have already shown, these boards are part of the participatory infrastructure created over the past 30 years. Even those that are constitutionally protected, such as the National Food Security Council, the National Human Rights Council and the National Social Assistance Council, among many others, have been made extinct or modified. Almost all of them have been transformed. Civil society representation has decreased as well as institutional support. These measures contain and limit the participation that was stimulated by the creation of this infrastructure.

In the field of policies for women, black people and LGBT+ people, the Bolsonaro government has acted not only through austerity policies, with continuous cuts to social policies, but also through a policy of discrimination. Its rhetoric, based on the defence of so-called traditional family values, has found support in the practical actions of its ministers. The new minister of women, family and human rights, Damares Alves, supports all sorts of conservative values and is an activist against abortion rights, even opposing abortion in cases of rape. In the field of human rights, the Comissão de Mortos e Desaparecidos Politicos (Committee on Victims of the Repression) is composed of several representatives of civil society and is responsible, among other things, for assessing the crimes of the military dictatorship (a term also disputed by this government). It recently had the members of its board deposed and replaced by those nominated by the government, including military personnel.34

Contrary to the democratic spirit of the 1988 Constitution and the subsequent practice of state-society relations in Brazil, the Bolsonaro government has attacked the constitutional principle of social participation and insulated the public bureaucracy from public engagement once again. This closes access to public policies through material, legal and symbolic resources and puts the country on an unpredictable route that begins with de-democratisation. And de-democratisation is a key component of Bolsonaro’s new political arrangement.

This agenda significantly affects social conditions. Discussing the future of the Brazilian health system and environment, the Lancet report mentioned above lists the initial measures of Bolsonaro’s far-right government and its implications for health: first, changes in reproductive health would affect adolescents; second: “A new decree to modify the Disarmament Statute on the registration, possession and commercialisation of firearms and ammunition will lead to increased availability of guns in a country that has one of the highest incidences of homicide and violent deaths in the world”;35 third: “A working group established by the Ministry of Justice and Public Security is evaluating the convenience and opportunity of reduced tax on cigarettes manufactured in Brazil” and fourth:

Several other new bills and constitutional amendments are currently under discussion at the National Congress to eliminate or considerably reduce the restrictions of the environmental licences for new infrastructure projects and other economic activities, and prevent the demarcation of new indigenous and protected areas, or even revoke existing ones to make way for the expansion of agribusinesses—policies that threaten Brazil’s environmental system.36

As a further example of these measures, Bolsonaro is giving “a free pass to pesticides”, which may have consequences for the health of workers and consumers.37

Bolsonaro’s agenda is very clear: political regression, a conservative agenda, preservation of Temer’s austerity measures and social setbacks, restriction of freedoms as far as possible, a stimulus to police violence38 and the disruption of human rights institutions. In the first months of Bolsonaro’s government there was an increase in police lethality. In 2018, deaths caused by police totalled 6,160; in 2019 initial data show that between January and July there were 1,075 deaths in police actions in the state of Rio de Janeiro alone.39 Those regressive political features are important to Bolsonaro’s economic project: democracy must be defeated as a prerequisite for unleashing the predatory forces active in Brazilian capitalism.

Bolsonaro’s economic project

Bolsonaro’s initial economic measures clearly reinforce two pillars of the middle income trap: first, the persistence and, probably, the deterioration of inequality; second, the lure of easy exploitation of natural resources—the predatory side of Brazilian capitalism.

In the long term, as mentioned earlier, Brazilian capitalism can be interpreted in terms of a contradictory relationship between predatory and innovative forces.40 Those innovative forces can be tracked by the incomplete formation of the Brazilian system of innovation. Predatory forces can be associated with the exploration of natural resources regardless of the environmental damage caused—therefore, with no significant use of research and development to discover and invent more environment-friendly processes. The identification of those two sides within Brazilian capitalism is important in order to highlight what may change now. This new political arrangement inherits strong predatory forces in capitalist dynamics.

Map 1: Regions of Brazil and the ten largest cities

This inheritance can be identified in Brazil’s recent economic history. It is illustrated by the “negative externalities” generated by the previous “commodities boom” of the early 21st century (figure 1 shows a phase of slight catching up between 2002 and 2010). The proportion of natural resources in Brazilian exports reached a peak of around 40 percent in 2011.41 The other side of the commodities boom was an increase in the numbers of dams used to store mining waste, especially in the state of Minas Gerais.42 These dams present a great deal of risk and have caused two disasters in Minas Gerais—Samarco in Mariana, on 5 November 201543 and Vale in Brumadinho, on 25 January 2019.44 Both involved human deaths, the devastation of regions and an ecological disaster.

In the Amazon region, there are reserves of copper, tin, nickel, bauxite, gold and iron ore. Mining is an issue involving huge amounts of greed, and part of the deforestation inherited by the current government was caused by mining.45 Those resources feed pressures for their exploitation—the temptation for predation and easy gains. Therefore, there is a continually renewed pressure to expand the areas for mining in the Amazon region. This pressure is strong and those projects threaten native people, protected areas and units of conservation.46 Protected areas often overlap with areas with large mineral reserves.47

Bolsonaro’s behaviour in a meeting with governors from the Amazon region which was planned, in principle, to discuss how to contain the fires in the region is also a signal and a warning. His main comments were on the extension of protected areas for indigenous people.48 But, on the same day, the first step was taken in a project to change the constitution in the Brazilian Congress to allow farming on indigenous peoples’ lands.49

Predatory forces were present throughout Brazilian economic history, a structural feature of Brazilian capitalism, including in the more recent period. As Maristella Svampa puts it:

Within the framework of the commodities consensus, Latin American progressive governments have opted for a predatory type of extractivism, as demonstrated by the enormous multiplication of development programmes based on large-scale extractive projects (gas, soy, oil, and minerals), whose social, environmental, cultural, and political consequences are systematically denied or minimised. Due to the characteristics of territorial appropriation and new social, ethnic, and gender-based inequalities, these extractive projects can only be imposed through a troubling setback in human rights and freedoms. The association between extractivism and the decrease in democracy becomes a recurrent event: without social licence, without consulting populations, without environmental controls, and with little state presence or even with it, governments tend not only to empty the already bastardised concept of sustainability of all content but also to manipulate forms of popular participation, seeking to control collective decision making.50

The issue now is the dismantling of institutions that could mitigate those strong forces—this is the role of Bolsonaro’s new political arrangement. This would give free rein to those predatory forces. Bolsonaro’s interference with the Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais (National Institute for Space Research, INPE) is an example of those policies. INPE had produced a report alerting readers to an increase in deforestation in the Amazon region. Bolsonaro’s reaction led to the dismissal of the head of the institute. According to an article in Science: “Many prominent scientists and environmentalists blame the increase in land clearing on Bolsonaro’s aggressive pro-development statements and policies, including the promotion of farming and mining on protected land”.51 There is clear evidence of the relationship between deforestation and the Amazon fires.52

The push towards mining in the Amazon region is clearly an explicit policy from Bolsonaro, as Reuters noted in 12 April 2019: “Bolsonaro says Rainforest Reserve May be Opened to Mining”.53 And Bolsonaro has proposed to make his son Eduardo ambassador to the United States, highlighting his intention to find partners in the Global North to explore mineral resources in the Amazon region, on indigenous people’s lands.54

We can understand Bolsonaro’s project from his rhetoric and his actions: on the one hand, incentives for predatory practices in the region, on the other, governmental actions dismantling regulatory and research agencies that could monitor those processes.55

The tragedy of the Amazon fires in late August 2019 is a result and a warning. Emboldened by Bolsonaro’s statements,56 settlers and/or farmers set fire to the forests to push deforestation—a criminal activity—and the end result was tragic: a crisis in the Amazon region. According to the New York Times: “The destruction of the Amazon rainforest in Brazil has increased rapidly since the nation’s new far-right president took over and his government scaled back efforts to fight illegal logging, ranching and mining”.57 A study by the National Institute for Space Research that used satellite imagery to monitor the extent of the fires in late August and compared that data with earlier data, concluded, “that there were 35 percent more fires so far this year than in the average of the last eight years”.58

These tragedies—dam collapses, Amazon rainforest fires—show the consequences of predatory actions within Brazil. This is a warning of what might happen if those forces become unregulated, unmonitored and emboldened by the support of a new political arrangement.

This new political arrangement organises Bolsonaro’s very clear and consistent economic project: to free the predatory side of Brazilian capitalism. This project is supported by major economic interests, starting with the giants of the mining sector. This project is consistent as it tries to dismantle the creative and innovative side of the Brazilian economy, putting the future of the country’s innovation system at risk since there is no need for science and technology to implement these predatory projects. An economic project grounded in predation, not innovation, does not need an educated population, a large university community or a civilised society.

Bolsonaro’s project of freeing the predatory dimensions of Brazilian capitalism is related to his government’s other economic measures, such as pension reforms and privatisation. The emphasis is not in creating new firms, new institutions or new sectors for existing firms. On the contrary, the priority is the transfer of existing assets to other owners. In this sense, public assets are open to predation by financial institutions. Such institutions are not pushed to fund new ventures or new firms related to emerging technologies and potential areas of evolution of the Brazilian economy, but are instead encouraged to manage the transfer of assets.

This seems to be the case with the innovation system, as the major proposal in Bolsonaro’s project for public universities is a private financial fund that would receive and manage universities’ assets.59

In summary, Bolsonaro has an economic project, and development is not part of that economic project. Bolsonaro’s project strengthens the predatory side of Brazilian capitalism, therefore it would reinforce the mining and other extractive activities of the economy. It aims for an insertion of the Brazilian economy into the international division of labour—as a mere supplier of natural resources; a passive insertion in the present reconfiguration of global capitalism. To push this predatory side of Brazilian capitalism, the political arrangement must be regressive, with attacks on human rights, democracy and social rights.

Bolsonaro’s project and resistance: an open-ended scenario

This tentative elaboration of Bolsonaro’s political and economic project is necessary for a broader analysis of today’s conjuncture in Brazil, as it puts forward the key question: will this project succeed?

The answer to this question depends on the interplay of this new political arrangement with other actors and movements. Important factors in this equation are Bolsonaro’s capacity to integrate large sectors of the Brazilian bourgeoisie—so far under the spell of his pledge to implement counter-reforms60—his ability to integrate other sectors of the Brazilian political right beyond the electoral scenario of 2018 and to keep his political electoral support and, most importantly, the resistance of Brazilian democratic and popular movements to this agenda. Probably, the most important political struggle now is the struggle for democratic freedoms.

We discussed the vitality of Brazilian civil society earlier in this article. Those forces are still alive in Brazilian society. And, as in other moments in recent Brazilian history, civil society groups and movements are fighting.

Several campaigns, mobilising people from different policy areas, are denouncing the increasing escalation of state violence led by Bolsonaro’s government. Demonstrations in areas such as agriculture, women’s liberation, education, social assistance and health policies have occurred all over the country, mobilising millions of people. Student movements, education unions and associations that, since the Temer government, have been mobilising against that government’s regressive tax measures, are fighting side by side with other movements to denounce and counterbalance the new government’s arbitrary measures. Thousands of people have taken to the streets in at least 173 cities in Brazil in defence of public education and against cuts in federal university budgets.61

On 13 and 14 August 2019, for example, thousands of women from different Brazilian regions marched towards Brasilia in the 6th Marcha das Margaridas (March of Daisies). This event brought together women from the countryside, forests, coastal regions and cities, and this year also saw the participation of indigenous movements. Although the march occurs every four years, with specific demands related to the life conditions of women in agriculture, this year their platform was “the struggle for popular sovereignty, democracy, justice, equality and freedom from violence”.62

The academic community, linked to social movements and participatory institutions, launched a campaign in defence of the councils and conferences—“O Brasil precisa de conselhos”—despite recognising the political limits of these spaces.63 The Bolsonaro government “impels researchers and other civil society actors to defend as necessary what they once understood as insufficient”.64 Although civil society is resisting, there are huge struggles ahead. Democracy is a key issue now.

The current transformation of the Brazilian economy shows the first signs of what might be a long-lasting deterioration. Data for GDP growth in the second quarter of 2019 show a slight recovery—a growth of 0.4 percent—that has been celebrated by some.65 This weak growth is related to a small improvement in employment rates—a reduction from 12.3 percent unemployment in the second quarter of 2018 to 11.8 percent in the second quarter of 2019; the last percentage equating to 12.6 million unemployed.66 However, this small improvement is related to an increase in informal jobs—now 41.3 percent of total employment67 and a consolidation of long-term unemployment—now 4.8 million, a record in Brazil.68 This may be a sign of a consolidation of a labour market in which low quality jobs are a growing share.

This might be articulated with the economic project of an uncontrolled predatory capitalism, because the creation of sectors in industry and services related to higher technology sectors is not on Bolsonaro’s agenda. The emphasis on mining and allied sectors cannot generate high-quality jobs. This is an important topic for further research.

To block the consolidation of such a scenario, the priority is to formulate a new programme that combines democracy, non-predatory development and social inclusion. Resistance needs to be combined with a collective and broad effort to reorganise this democratic programme in a way that includes an assessment of the previous post-dictatorship years, its conquests and its failures (the major failure since 1988 has been that of not overcoming the middle income trap).

Bolsonaro should be impeached as soon as possible in order to prevent further harm to the already fragile democratic, environmental and social conditions. But this democratic priority must be combined with the reconstruction of the Brazilian innovation and welfare system, in a stronger way than in the past, so as to set the preconditions for facing new challenges. There is a need for a new conception of development—post-extractivism69—that understands the current challenges put forward by climate change and the challenge to begin a transition to a new paradigm of natural resource use. There is evidence that it is necessary to keep natural resources unexplored, fossil fuels unburned70 and cerrados (savannas) and forests preserved.71 The democratic and popular movements and the political left must see this evidence as a stimulus to elaborate a new programme that includes measures to accelerate the transition towards environment-friendly sources and new materials (that allow the current mineral reserves to remain unexplored) and more intelligent ways of producing food. The answers to those combined challenges call for a larger involvement in science and technology, and a stronger priority given to innovation vis-à-vis predation.72

Cláudia Feres Faria is an associate professor in the Political Science Department of Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. She coordinates the research group CEDE (Centre for Deliberative Studies).

Eduardo Albuquerque is professor at the Department of Economics and Cedeplar, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Brazil, and author of the book Agenda Rosdolsky (2012, Editora UFMG).

Notes

1 Fernandes, 2019. We would like to thank the organisers and participants of the 18th Seminário de Diamantina (https://diamantina.cedeplar.ufmg.br/2019/), the main theme of which was “the crisis of mining”: this article benefited from presentations, sessions, discussions and talks that took place there between 19 and 23 August 2019. We would also like to thank Rodrigo Castriota for his suggestions of important references for the understanding of a rich literature in extractive operations and their implications for the environment and economies, Ana Hermeto and her recommendations to understand unemployment and labour markets in Brazil, Antonio Thomaz Gonzaga da Mata Machado for his comments on a previous version of this article, Tiago Camargo for his research assistance in the preparation of this final version and the editors of International Socialism (Alex Callinicos and Camilla Royle) for their comments and suggestions. The errors in this article are ours.

2 See the interview with General Augusto Heleno by Piauí—Victor, 2018, p21.

3 Barba and Wentzel, 2016. See Albuquerque, 2016, on the background to Dilma’s impeachment.

4 Franz Neumann points to the selectivity of the Weimar Republic’s judicial system as one of the factors that might have opened room for the rise of Nazism: “In the center of the counter-revolution stood the judiciary”—Neumann, 2009, pp20-23.

5 José Murilo Carvalho compares the Brazilian military with that of Argentina and Chile, which had “apologised publicly for the excesses committed and brought to justice those accused of committing crimes”—Carvalho, 2019, pp17-18.

6 For notes on his biography, see Anderson, 2019 (section II—“Bolsonaro”) and the section “Portrait of a Thug”, in Webber, 2019.

7 In Brazil participation in elections is mandatory so the abstention rate is expressive in this election: 21.3 percent. There were also 7.4 percent null votes and 2.1 percent unmarked ballots—Fernandes, 2018.

The composition of the Brazilian Congress tilted towards a more conservative position and a more fragmented composition—there are 31 different parties represented. In the elections, PSL, Bolsonaro’s far-right party, got 52 seats. Broadly, the centre-left (PT, PDT, PSB, PCdob, Rede, PV) and left parties (PSOL) got 141 seats, centre-right parties (PSDB, MDB, PR, PPS) have 104 seats and right-wing parties (DEM, PP, PSD, PRB, SDDE, PODE, PTB, PSC, NOVO, PRP, etc) at least 174 seats—Cunto, 2019. Bolsonaro’s proposed changes to the pension system were approved by a comfortable majority of 370 votes to 124—Cunto and Ribeiro, 2019.

8 The unpredicted casualties of the rise of the far-right were PSDB, PMDB and DEM (centre-right and right-wing parties), whose presidential candidates performed badly in the 2018 elections.

9 Furtado, 1992, pp37-59.

10 This contradiction is not specific to Brazilian capitalism, it is an aspect of global capitalist dynamics, a global contradiction in capitalism. As Alex Callinicos points out, on the one hand: “Capitalism thus continues to be heavily invested in the fossil fuels industries, and Donald Trump is acting as a megaphone for these interests”, on the other hand “firms are responding to the official, sluggish efforts to move towards a net carbon neutral economy by exploring new opportunities for profit. This is easier for relatively new companies that are less heavily invested in the existing energy complex”—Callinicos, 2019, pp7-8.

11 Albuquerque, 2019, pp51-53.

12 Some causes of the economic crisis that led to Dilma’s impeachment are discussed in Albuquerque, 2016.

13 A broad analysis of multiple dimensions of this structural crisis is presented in Andrade and Albuquerque (eds), 2018. There are 23 chapters, each one dealing with a particular dimension of that crisis.

14 Neri, 2019.

15 Neri, 2019, pp3 and 12. Poverty is defined by a personal monthly income below R$233.00 (about 57 US dollars).

16 Lameiras and others, 2019, p2.

17 Lameiras and others, 2019, p4.

18 Castro and others, 2019, p353.

19 See the “Breach of Ethics” investigation by The Intercept on how the former Judge Sérgio Moro and some public prosecutors collaborated illegally during key moments of the Lava-Jato operation—Fishman and others, 2019.

20 The limits of Brazilian democratisation after 1988 and even during the Workers Party’s government are shown by Carvalho, 2019, Paula, 2003 and 2005, and Oliveira, 2003.

21 Tilly, 2007, p23.

22 Avritzer and Faria, 2019.

23 Barreto, 2011.

24 Barreto, 2011.

25 Lopez, 2018.

26 Alvarez, 2009; Lavalle and Bueno, 2011.

27 Santos, 2017, pp64-65.

28 Tatagiba and Galvão, 2017.

29 Abers, Serafim and Tatagiba, 2014.

30 Sandro Mezzadra and Brett Neilson, discussing the mobilisations of 2013 in Brazil mention “indigenous resistance against dams” as one of the streams of those movements—Mezzadra and Neilson, 2019, p168. It is important to stress the continuity in the problems related to predation. But the election of Bolsonaro means a qualitative change—a negative, regressive qualitative change—to be discussed in the next sections.

31 Tatagiba and Galvão, 2019, p91.

32 Valor Econômico, 2018.

33 Carvalho, 2019.

34 Biasetto, Leali and Cople, 2019.

35 Castro and others, 2019, p354.

36 Castro and others, 2019, p353.

37 Coelho and others, 2019.

38 See Mello, 2019.

39 Mazza, Rossi and Buono, 2019.

40 Albuquerque, 2019, p54.

41 During this period, Svampa, 2015, identifies a “commodities consensus”, that included all governments is South America, including Lula’s and Dilma’s.

42 The map in Gama (2019, slide 4) shows the distribution of those dams in the neighbourhood of Belo Horizonte. Galéry (2019, slide 9) shows that the quality of iron ore in Minas Gerais leads to a production process with 55 percent processed iron ore and 45 percent waste. In other words, for each ton of exported iron ore there is almost 0.9 ton of mining waste to be stored in dams. This form of iron ore processing suggests a lack of investment in research and development in order to generate more environment-friendly processes.

43 Romero, 2015.

44 Andreoni and Shasta, 2019; Phillips, 2019.

45 Sonter and others, 2017.

46 Rittner, 2018. Murguía, Bringezu and Schaldach, 2016.

47 Compare the maps in CPRM, 2002, pp6 and 46.

48 Truffi and Murakawa, 2019.

49 Valor Econômico, 2019b.

50 Svampa, 2015, p71.

51 Escobar, 2019a.

52 Escobar, 2019b.

53 Fonseca and Spring, 2019.

54 Piva, 2019.

55 An article from The Intercept shows how old plans for the Amazon region may be integrated to Bolsonaro’s project—Dias, 2019.

56 Filho, 2019.

57 Symonds, 2019.

58 Lai, Lu and Migliozzi, 2019. The first map shown in this article is helpful in understanding the history of Amazon deforestation, as it shows the boundaries of the Amazon region, the “existing forest”, “deforestation through 2018” and “fires in August” 2019.

59 According to a weekly newspaper, Veja (27 September 2019), there was a meeting with people from the real estate sector to discuss how they could profit from land owned by public universities. In the original project for public universities, there are two articles that put the assets of public universities under the administration of (still unexplained) private financial funds: see articles 8 and 9 of this governmental legislative project—called Future-se (the full project is available at http://estaticog1.globo.com/2019/07/19/programa_futurese_consultapublica.pdf)

60 According to the newspaper Valor Econômico, a gathering of leading Brazilian firms sent the message that the federal government should persevere in their “reforms”, even at the risk of slow growth and under the threat of a global recession—>Valor Econômico, 2019a.

61 Borges, 2019.

62 Motta and Teixeira, 2019.

63 To follow the campaign and other initiatives, see www.democraciaeparticipacao.com.br

64 Abers, 2019.

65 Lamucci, Conceição and Bôas, 2019.

66 Bôas, 2019a.

67 Bôas, 2019b.

68 Carrança, 2019.

69 Lang and Mokrani, 2013.

70 Jakob and Hilaire, 2015.

71 Soterroni and others, 2019; Abramovay, 2019.

72 The concept of innovation must be reassessed in order to include the challenge of climate change. In Joseph Schumpeter’s classic definition (1911), one of the five types of innovation he identified was the discovery of new sources of raw materials. Since the Industrial Revolution, with coal as a key source of energy, and after the era of the combustion engine, with oil as a key energy source, the levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere have reached dangerous levels—see Budd, 2015, p2. Therefore, driven by the profit motive, the orientation of technological progress from those two fossil fuel-based technologies has led to the current threats of climate change. Chris Freeman (1996) suggests policies for a re-orientation of technological progress towards more environment-friendly new technologies. This must be a new benchmark for the definition of innovation. By contrast, new sources of raw materials that bring negative externalities (such as fracking) might be seen as a form of predatory exploration of natural resources.

References