Mike Davis’s book Planet of Slums provides a brilliant account of the rapid growth of urban areas and megaslums, created by the hammer blows of the global restructuring of the world system since the 1970s.

Though Davis’s principle arguments concern the extraordinary growth of “megacities”, he also raises vital questions about the role of the working class in a world transformed by “market reforms” since the mid_1970s.1 This article focuses on some of Davis’s claims about the working class, and concentrates exclusively on the situation in sub-Saharan Africa. There are two important reasons for this. One is that Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAPs), implemented across the developing world, have had their most devastating effect here. The other is that Davis’s assertion that, with the growth of the African slum, “myriad groups” of the informalised poor have dislodged the African working class is open to doubt.

Davis’s argument

Africa has seen the “supernova growth of a few cities like Lagos (from 300,000 in 1950 to 13.5 today)” and “the transformation of several small towns and oases like Ouagadougou, Nouakchott, Douala, Kampala…and Bamako into sprawling cities larger than San Francisco or Manchester”.2 As cities stretch out to include small towns and previously rural villages, we are confronted with “the emergence of polycentric urban systems without clear rural/urban boundaries”. 3

Historically, Davis argues, the movement to urban centres was meant to reflect the growth of manufacturing and the concomitant increase of wage labour—Marx’s industrial proletariat. This development was also meant to see a growth in agricultural productivity to feed swelling cities through the application of large-scale modern farming techniques. But the opposite has occurred. “Urbanisation without industrialisation is an expression of an inexorable trend: the inherent tendency of silicon capitalism to delink the growth of production from that of employment”.4 The culprit, Davis explains, is the twin evils of the 1970s debt crisis, and the IMF and World Bank’s restructuring of Third World economies. So today urbanisation becomes synonymous with falling wages, factory closure and massive unemployment.

Davis asks, “How has Africa as a whole, currently in a dark age of stagnant urban employment and stalled agricultural productivity, been able to sustain an annual urbanisation rate (3.5 to 4 percent) considerably higher than the average of most European cities (2.1 percent) during the peak Victorian growth years”?5 Though cities are no longer hubs of formal employment, under the pressures of IMF and World Bank enforced agricultural deregulation millions flee rural poverty for urban slums. In Kenya, for example, 85 percent of the population growth in the ten years after 1989 was soaked up in the slums of Nairobi and Mombasa. Some sub-Saharan African countries have literally been turned into mass slums. In 2003, 99.4 percent of the population were “slum-dwellers” in Chad and Ethiopia.

While the poor have been consigned to the global slum, the wealthy have built fences and gun towers around their neighbourhoods. There are almost 300,000 registered private security guards defending these gated compounds and approximately 2,500 private security firms in South Africa alone.6

In tandem with the growth of the megaslum has been the collapse of formal employment, which Davis blames on “a new wave of SAPs and self-imposed neoliberal programmes”, which have “accelerated the demolition of state employment”.7 While salaries of the jobs that have remained in the formal sector have shrunk almost to invisibility, there has been a massive growth of informal work. This is work that lives outside the factory and office, and might involve people trying to survive by selling vegetables in markets or CDs to passing motorists. Since 1980, says Davis, “economic informality has returned with a vengeance, and the equation of urban and occupational marginality has become irrefutable and overwhelming: informal workers, according to the United Nations, constitute about two thirds of the economically active population of the developing world”.8

Slums, in Davis’s account, symbolise the total reconstitution of class structures in the Third World. Unemployed slum-dwellers are not the urban proletarian powering political transformation. At the end of Planet of Slums we are left with a question: “To what extent does an informal proletariat possess that most potent of Marxist talismans: ‘historical agency’?”9 But to what extent, in the picture drawn by Davis, are they a “proletariat” at all? In the world of neoliberal slums there is “no monolithic subject”, but “myriad acts of resistance”, that emerge from a chaotic plurality of “charismatic churches and prophetic cults to ethnic militias, street gangs, neoliberal NGOs and revolutionary social movements”.10

What’s going on?

Traditionally the African working class has been a small proportion of the global proletariat. So, in 1995, 40 percent of the world’s estimated 270 million industrial workers were found in OECD countries, but only 5 percent in Africa.11 But even these figures, more than ten years old, exaggerate the global share of industrial workers on the continent. Though there has been a global increase in wage labour, with the restructuring of production there has also been an explosion of unemployment. Chris Harman describes this unevenness: in “most regions (although not in most of Africa) there is also a growth of the number involved in wage labour of a relatively productive sort in medium to large workplaces. But even more rapid is the expansion of the vast mass of people precariously trying to make a livelihood through casual labour”.12

In Africa there has been a dramatic “informalisation” from the 1970s, exacerbated by the unravelling of the corporatist state—often triggered by IMF-led SAPs. Ten years of these programmes meant that by 1991 a number of African countries saw a fall in formal wage employment: an estimated 33 percent in the Central African Republic, 27 percent in Gambia, 13.4 in Niger and 8.5 percent in Zaire (today’s DRC). In the same period the government in Zimbabwe pursued policies involving privatisation and the closure of state companies deemed unprofitable by Western donors, the IMF and the World Bank. More than 20,000 jobs were lost between January 1991 and July 1993. In 1993 unemployment had reached a record 1.3 million from a total population of about ten million. Tor Skalnes reported 25,000 civil service jobs lost by 1995, while “inflation rose and exports declined”.13

In South Africa, the “success” story of the continent, official unemployment was 16 percent in 1995 and rose to 31.2 percent in 2003, but if those who have given up the hunt for work are included the figure rises to 42 percent. Formal employment collapsed in many “traditional” sectors. During the 1990s the number of jobs contracted 47 percent in mining, 20 percent in manufacturing and 10 percent in the public sector.14

One graphic example of deindustrialisation elsewhere on the continent is the textiles and clothing industry. Much of the original growth in this sector in the 1960s and 1970s was a result of governmental policies of producing local substitutes for previously imported goods. Textiles and clothing expanded until the sector comprised between 25 and 30 percent of those formally employed. When the World Bank and IMF insisted that governments “open” their economies to foreign imports, the resulting job losses were devastating. In Ghana in the late 1970s the industry employed 25,000 people; by 2000 only 5,000 were employed. A similar picture emerges in Zambia, where only 10,000 worked in the sector in 2002, down from 25,000 or more in the early 1980s.15

When the Kenyan economy was prized open in the 1990s, new and secondhand clothes (mitumba) from the US and the EU, together with the increases in the cost of electricity, made it almost impossible for Kenyan manufacturers to function. An industry that had been relatively healthy in the 1980s, employing approximately 200,000, almost collapsed. Approximately 70,000 factory and mill jobs disappeared. By 2004 fewer than 35,000 people were employed in Kenya’s clothing export sector.16

The growth of the informal sector has been a direct result of the collapse of traditional industries. Whether this has led to the collapse of previously solid class identities or to their reformulation is open to question. But where the working class does exist it has played a cohesive role in relation to the “myriad” groups fighting neoliberalism. It is not the case that the formally employed are cut off from informal workers by their “privilege”, or that they live in “formal housing” away from the mass of slum-dwellers.

There has been a long academic debate about the nature, and even existence, of an African working class. Even the left wing scholar Basil Davidson, who spent a lifetime defending progressive social movements on the continent, could write dismissively that the working class was unable “to achieve the solidarity and coherence that could have moved them towards empowering socialist political movements”.17 Ruth First argued that African patterns of development had created a hybrid class (the “-peasantariat”), founded on a linked rural and urban identity.18

At times Davis’s slightly apocalyptic account repeats this questioning of the capacity of a Third World, or African working class, to play its “historical role”. It may have done so in the past, but now, under the impact of neoliberalism, it is once again a hybrid slum-dweller, unable to lead new social movements on the continent. Yet actual class reconfiguration does not suggest a working class entirely dislodged from its “historical agency”.

The case of Soweto

Davis’s account is problematic as Africa is not, uniquely or universally, a space of undifferentiated deindustrialisation where the working class has been uprooted from formal employment. To take one example, Davis writes about Soweto’s “backyards” and how “residents have illegally constructed shacks that are rented to younger families or single adults”.19 Soweto is South Africa’s largest township, home to an estimated two million residents, twice the number of those recorded in a survey eight years ago.20 It is a place of phenomenal diversity, including wealthy suburbs serviced by modern shopping malls and a golf course, as well as “respectable” working class communities in modest apartheid-era housing. These areas sit cheek by jowl with squatter camps and informal settlements that seem to exemplify Davis’s descriptions of Southern slums.

But recent research conducted by the Centre for Sociological Research (CRS) in Johannesburg suggests a reality quite different from the fashionable view that unemployment in South Africa has “polarised the labour market by increasing the resources to some of the 6.6 million in the core who are formal, permanent workers while at the same time reducing the resources” to the rest.21 The research suggests far more fluidity between the “core” of 6.6 million and the rest. In a Soweto-wide survey of more than 3,000 people in 2006, respondents were asked to describe their lives.22

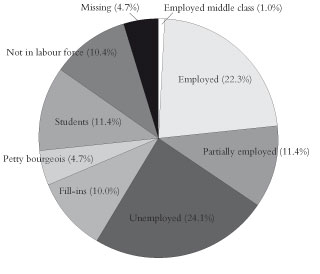

The pie-chart (figure 1) presents a picture of life ravaged by unemployment in Soweto. Some 50.1 percent of the respondents in the survey were not in formal employment. This requires some explanation. “Partial workers” are people who explained that they did not work but occasionally did piecework, while “fill-ins” were those who were engaged in small businesses, similar to the “petty bourgeoisie”, but they explained that they would accept work if they were offered. These “businesses”—in the much celebrated “entrepreneurial” world of the new South Africa—might be hawking sunglasses or bootleg videos by the side of the road, or perhaps more often in Soweto selling a few fruit and vegetables on the pavement. None of these people, a full 26 percent, are counted in the official unemployment statistics. These figures present a devastating verdict on the laisser-faire policies of both Nelson Mandela and Thabo Mbeki’s governments.

Figure 1: Soweto’s labour force

Produced by CSR, November 2007

But do these statistics imply that mass unemployment has created a new class of the wageless poor excluded from the world of work, with the working class now a small and privileged group living outside the township_slum whose interests are separate from the majority of the urban poor? A closer look reveals something quite different. If we examine the Sowetan household we see an extraordinary mixing up of the different and seemingly divided groups of the poor. For example, in only 14.3 percent of households were there no employed people. This means that less than a sixth of households were entirely unemployed or self-employed. We can go even further. In 78.3 percent of households there was a mix of adults who were employed, self-employed and unemployed. There is no impenetrable wall between work and unemployment, as the “poor” and “middle class” live side by side, as family members and friends. Poverty and relative prosperity are connected in the household.

What does this mean in terms of people’s lives? To take one case study, “Mr Khumalo…was a teacher and now works as a driver. He lives with his wife, who is a nurse, and his three children. One child is at university. He supports his brother and his sister. His brother has been unemployed for two years after the factory closed.” Mr Khumalo described himself as “working class…trying to push to be middle class”. The employed and the unemployed are integrated at the level of the household. “These stories show that the polarisation of the labour market, far from making the stable employed into a privileged layer, may have the reverse effect of increasing the responsibilities on their wages”.23 The effect is to destabilise the formally employed.

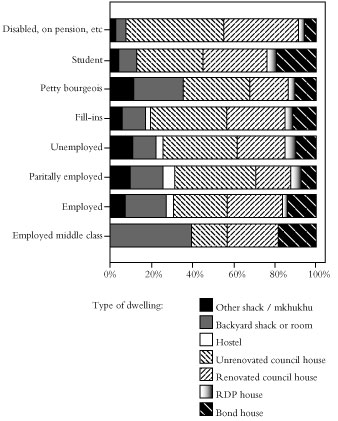

Soweto is also an extraordinarily mixed urban space. The majority of people do not live in shacks. The table below (figure 2) shows the spread of housing types across Soweto. Some 75.7 percent live in a range of formal housing, from council housing to recently built government housing. But there is still a chronic shortage of housing in Soweto. A shocking 23.7 percent of people live in “informal” shacks, hostels or “backrooms” (often corrugated iron extensions tacked onto the side of brick houses). In addition, new housing has simply not been built since 1994 in anything like the quantities required (or promised). According to the statistics below, RDP houses, as this housing shock is popularly labelled (known after the Reconstruction and Development Programme introduced briefly after 1994), account for only 4.2 percent of the total housing types in Soweto. This also reflects the fact that most RDP houses are built outside township boundaries, and not in spaces where people need them—close to family networks, work opportunities and facilities. Although the unemployed, partial workers and fill-ins are more likely to be found in the shacks and slums of Soweto, people from each group are found in all housing types (with the exception of hostels). This is not a picture of an informal proletariat living exclusively, or even mainly, in shacks and slums.

Figure 2: What kind of houses do people live in?

Produced by the CSR, November 2007

| Housing type | Percent |

|---|---|

| Unrenovated council house | 34.8 |

| Renovated council house | 19.9 |

| Council house with major rebuild or extension | 6.1 |

| Bond house | 10.7 |

| RDP house | 4.2 |

| Backyard shack | 6.9 |

| Backyard room | 6.3 |

| Other shack/mkhukhu | 7.6 |

| Hostel | 2.9 |

| Brick house | 0.4 |

| Other | 0.4 |

Put simply, and limited to Soweto, these figures tell us that the jobless and formally employed are not hermetically sealed off from each other, in terms of either the household or neighbourhood. Nor are they clustered in the “informal” slum settlements of Soweto. The graph below (figure 3) shows that employed and partial workers also live in shacks, though in smaller numbers than the self-employed, while the majority of the self-employed, like the majority in all these categories, live in a brick house of some kind.

Figure 3: Where do different sections of Soweto’s labour force live?

Graph produced by the CSR, November 2007

There is, in addition, an important level of complexity to the concepts of unemployment and informality. In Soweto there are several distinct categories among the labour force included under the umbrella of “informality”. So the unemployed are those completely out of work, who do not vend, sell or “fill in” on temporary jobs, and this group was 21.92 percent of the population; “partial workers” are those who do occasional piece_work and may work full time for a week or a month interspersed with periods of unemployment. This means that Davis’s wageless informal proletariat, made up of those who struggle precariously as vendors and in small businesses, resemble the “fill-ins” and the “petty bourgeoisie”, who make up a mere 14.65 percent of the total labour force.

This is not to deny that the effects of unemployment have had a dramatic and devastating effect on the poor. The implication from the survey is that almost all families have been shaken by the hurricane of job losses. This has important consequences for social unrest. If there is no clear divide in the world of unemployment, informal work and formal employment, the potential for a crossover of protests exists. The explosion of “service delivery” uprisings in South Africa over the past four years has seen communities erupt in riots and protests against the lack of basic services. In 2005, for example, there were 881 recorded protests.24 Though the number of protests may have dropped off from this high point, the levels remain impressive. The public sector general strike in June 2007 was the largest strike since the end of apartheid, pulling many people into trade union action for the first time. The potential cross-fertilisation of these struggles—of community and workplace—does not live only in the mind of activists, but, as the survey suggests, expresses the real household economy of contemporary South Africa.

Soweto seems to point to a confused reality. The South African township and slum might be viewed as a meeting point for trade unionists, university students, graduates, the unemployed and informal traders. Though the spectre of unemployment affects all layers of society, these groups are not permanently cut off from each other and can be found in the same household supporting each other. Though we can not easily generalise from the experience of Soweto, there seems a reasonable chance that the mix of the formally and informally employed at the level of the household, and their intermingling fates, in diverse urban spaces could also be found in other Southern cities.

Femi Aborisade also sees an inclusive process at work. Even where the household combination of formal and informal employment is absent, “others have come to realise that the lot of the workers determines their own lot and that indeed they have a common interest. When workers are not paid or are poorly paid the poor peasant farmers and the poor petty traders (mainly women) know from their own experiences that their sales suffer. In an age of increasing unemployment, there are several dependants on the worker, and they have come to appreciate that their interests and that of the worker (who sustains their survival) are the same”.25 These relationships perpetuate cultural diversity within class formations, where a dual consciousness may exist among people who have maintained a relationship (and social rules) from their rural world.

Wage labour and neoliberalism

The current wave of global restructuring has devastated the continent with dramatic unevenness. Davis’s picture of Africa’s “dark age” of deindustrialisation and agricultural stagnation cannot be simply replicated across the continent. Davis presents Kinshasa (capital of the DRC) as an apocalyptic vision of the future city-slum made up of an almost entirely informalised population. But the particular circumstances in the DRC—including war waged almost without end since 1998—will not be easily reproduced in Africa (and even less so across the developing world). While there are important areas of near complete collapse, in other parts of the continent there has been the important growth of wage labour recently, linked to the global commodity boom.26 These processes of capitalist growth on the continent are inherently contradictory, uneven and temporary—if that boom blows, so can those jobs. The memory of the last collapse in formal employment and the reality of mass unemployment weigh heavily on the minds of those urban workers. While this insecure world of wage labour helps determine (and discipline) their behaviour, there is no question that the African proletariat exists.

Capitalism consigns huge numbers of the population to idleness, but it can pull many of these people back into wage labour when there is expansion. In limited, though significant, areas on the continent this has been the recent experience. The constant ebb and flow into the labour force has become one of the permanent features of wage labour under neoliberal capitalism. What this suggests is that there are many people outside of the formally employed who have some experience of a workplace, however irregularly. This contact with wage-labour will affect their understanding of solidarity and the “class struggle”. The same could also be said for those retrenched in the jobs massacres over the past decade.

Though the rapid deindustrialisation of Africa is indisputable, recent countervailing tendencies have seen the development of certain industries and the creation of jobs in areas previously decimated by the economic crisis. In recent years there has been an impressive recovery of many of the jobs lost in the textiles and clothing sector discussed above. Take Lesotho, where most formal sector jobs are in the rag trade. In 2006 Hong Kong and Taiwanese textiles firms in the country repackaged themselves as “ethical” manufacturers for a US market; thousands of jobs were created.27 Though approximately 5,000 jobs were lost in the clothing sector in Madagascar in 2005, new markets were found and the sector was expected to grow through 2007-8.28 Nor is job growth only found in the textile industry.

The new scramble for Africa has seen renewed interest in the continent’s oil reserves and minerals, which has also had the effect of creating employment in extractive industries. One notable actor in these developments is China, whose role on the continent has received substantial, if inaccurate, discussion.29 Chinese investment on the continent has grown by giant steps. The volume of trade has increased from $3 billion in 1995 to $55 billion in 2006. Though this figure amounts to only 10 percent of Africa’s total trade (compared to 32 percent with the EU and 18 percent with the US), it is projected to keep growing to $100 billion by 2010.30

Chinese involvement in African mining has seen previously abandoned mines reopened. Though the Chambishi copper mine was the site of the worse mining disaster in Zambian history in 2005, when 52 workers were killed, it also represents an area of formal sector expansion. When the mine was purchased by a Chinese state-owned enterprise in 1998, employment was boosted to 2,200 from 100.31 However, in the new privatised world of contemporary Zambia nothing is the same. Formal jobs rarely return in the same shape, and few of the miners who are now employed in the reopened Zambian copper mines have pensionable contracts, a situation that contrasts dramatically with the previous practices.32 Today mining communities have been ravaged by HIV/Aids, and little exists in the way of healthcare. Housing that was provided for miners does not exist on any meaningful scale, and townships, where most workers now live, are without proper services. The effect of years of privatisation has also meant that the partial “recovery” has not benefited the national state. So when copper was $2,280 a ton in 1992 the state-owned mining sector earned the Zambian government $200 million from 400,000 tons of production. In 2004 at similar production levels but with copper selling at an increased price of $2,868, only $8 million was provided by private mines to the state treasury.33 There is no more eloquent example of the catastrophic effect of privatisation on the continent.

Other jobs have been created in diverse sectors and countries from the investment of Chinese money across the continent. A private Chinese conglomerate in Nigeria involved in manufacturing, construction and other projects has 20,000 employees. State-owned Chinese firms in Nigeria have created 1,000 to 2,000 workers making shoes and textiles, while the Urifiki Textile Mill in Tanzania, another Chinese state-owned factory, has 2,000 workers. The controversy surrounding the involvement of the China National Petroleum Company in Sudan does not interest us here, but its claims of job creation do. The company has made the bellicose assertion that it has provided jobs for “more than 100,000 Sudanese while contributing to other employment sectors as the oil industry has grown”.34 Even with the obvious exaggerations these are significant figures.

None of this evidence is presented to suggest that Africa’s contemporary economic position is positive. On the contrary, the continent remains an overwhelmingly marginal recipient of the flows of Foreign Direct Investment, and many regions remain economically devastated. The effect of almost 30 years of IMF and World Bank led structural adjustment has created bomb-craters of destruction across the continent that cannot be easily filled. But the picture is not one of Davis’s universal collapse and near-apocalypse. The continent has seen economic growth and job creation, and will continue to do so—even if the growth remains uneven and inherently parasitical.

Recomposition of class and protest

The recomposition of class is undeniable, but it has not always led to a weakening of solidarity or the “class struggle”. In the late 1970s the global crisis meant that loans turned into debts and national adjustment, and restructuring became a requirement for further loans. More and more African states saw their macroeconomic policies shaped by the conditions imposed by IMF and World Bank boffins. The result was an epoch of social unrest that Davis describes.35

This started in Egypt in 1977, when the government’s decision to raise food and petrol prices as part of a programme of financial stringency under the auspices of the IMF provoked fierce rioting in major cities across the country. As has been described by David Seddon and John Walton, the first wave of struggle was based on wide coalitions of the popular forces, though the working class was usually centrally involved through the trade union movement.36 The impact of unrest depended on the participation of the wider groups, including the lumpen-proletariat of the slum, unemployed youth, elements of the new petty bourgeoisie and university students. Directed predominantly towards current economic reforms and austerity measures, they also contained elements of a critique of regime legitimacy and deployed notions of social justice. In most cases they served to redefine the terrain of struggle and to provide the basis for the emergence at a later stage of political movements aimed at changing governments rather than just policies. The point to highlight is that these protests involved a frequently very well organised and formally employed working class.

A second wave of protests broke out at the start of the 1990s. This wave of popular protest, now more explicitly political and with more far-reaching aims and objectives, spread across the continent like a political typhoon. From 1989 protests rose massively across sub-Saharan Africa. There had been approximately 20 annually recorded incidents of political unrest in the 1980s; in 1991 alone 86 major protest movements took place across 30 countries. By 1992 many African governments had been forced to introduce reforms and, in 1993, 14 countries held democratic elections. In a four-year period from the start of the protests in 1990 a total of 35 regimes had been swept away by protest movements and strikes, and in elections that were often held for the first time in a generation.37

Again these revolts are not only meaningful as new forms of “post_formal” resistance, but equally as ones often led by a formally employed working class. The social chaos that had been whipped up by the structural adjustment storm did bring new political forces into play, but they did not displace trade union organisation. On the contrary, it was more often than not unions—together with and frequently “leading” a variety of other forces—which forced regimes onto the defensive in Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, the Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Congo, Côte d’Ivoire, Gabon, Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, Lesotho, Madagascar, Mali, Mauritania, Nigeria, Swaziland and Zaire. Even when governments were not replaced, the pattern was similar across the continent, and trade unions, according to John Wiseman, “sought not simply to protect the work-place interests of their members but have endeavoured to bring about a restructuring of the political system”.38 During this second wave of protests in the 1990s trade union movements displayed greater independence and militancy than at any time in their history on the continent, and they did all of this in a world transformed by neoliberalism. Even in Kinshasa, the capital of Congo-Zaire that Davis privileges in his account as typical of life in the city-slum, the early 1990s saw a political movement heavily influenced by trade unions that threatened to remove Mobutu in what has been described as the Congo’s “second revolution”.39

Nowhere on the continent were these transformations clearer than in the struggles that shook Zimbabwe from 1996. Initially the struggle was expressed in strike action and spread from workplace to student protests and community struggles. Public sector strikes were punctuated by “bread riots”, as poor neighbourhoods near Harare exploded in rioting in January 1998, while students fought against the privatisation of catering facilities. All these elements combined with a growth in political demands. The disparate voices coalesced around the central, indeed leading, role played by the Zimbabwe Congress of Trade Unions (ZCTU). In many ways this typified Davis’s characteristion of “myriad acts of resistance”—but with a working class (often deindustrialised and weakened) still playing a central role.

The struggle formed the backdrop for the formation of the Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) which almost toppled the regime in elections in 2000. The case is put most forcefully by the former student leader at the University of Zimbabwe, Brian Kagoro, referring to a period of activism in the mid-1990s:

So you now had students supporting their parents on their student stipends which were not enough, because their parents had been laid off work. So in a sense as poverty increases you have a reconvergence of these forces. And the critique started…around issues of social economic justice, [the] right to a living wage…students started couching their demands around a right to livelihood.40

Myriad forces converged across numerous countries, and spoke of both the devastation of structural adjustment but also the explosive consequences of this destruction. Groups previously separated from each other found that solidarity was an instinct born of common experiences. Students no longer simply dipped into the social world outside their campus, as they passed through university in transition to formal sector employment. Along with other groups also once conceived as privileged (teachers, civil servants and “professionals”), students became an intimate part of the urban poor and unemployed. As early as 1994 Mahmood Mamdani wrote that “previously a more or less guaranteed route to position and privilege, higher education seemed to lead more and more students to the heart of the economic and social crisis”.41

Pauperisation across the whole continent has been “the heavy artillery with which it batters down all Chinese walls” between different social groups.42 But it has not triggered the total informalisation of the African proletariat, which still exists and still has the potential to lead movements for social transformation.

Contemporary social movements bring together heterogeneous groups that relate to a formally constituted working class. However, these movements—and the processes of class formation—can only be fully understood in the context of popular struggles, and the actual moments of protest and resistance. The answer to Davis’s brilliant, though gloomy, account is in the real course of events. As Alex Callinicos puts it, commenting on a series of strikes in Africa, “Sub-Saharan Africa…is host to many great slum settlements—but is also the site of a series of major mass strikes. This year started with a general strike in Guinea-Conakry…South Africa and Nigeria, have been hit by major strikes…these struggles…confirm that the organised working class is a powerful social and political actor in Africa”.43

The dynamic reality of class struggle on the continent reveals a working class, albeit reformulated, playing a central role both in the movements for democratic change and in the narrowly defined “economic” struggles that punctuate daily life on the continent.

Notes

1: Davis, 2006, p7.

2: Davis, 2006, p8.

3: Davis, 2006, p10.

4: Davis, 2006, p14.

5: Davis, 2006, p15.

6: “We Guard Millions, But Are Paid Peanuts”, Green Left Weekly, April 2006.

7: Davis, 2006, p163.

8: Davis, 2006, p176.

9: Davis, 2006, p201.

10: Davis, 2006, p201.

11: Quoted in Harman, 2002, p23.

12: Harman, 2002, p25.

13: Zeilig, 2007, p107.

14: Quoted in Bond and Desai, 2006, p239.

15: Quartey, 2006, p136.

16: Otieno, 2006, p19.

17: Davidson, 1992, pp232-233.

18: A combination of rural and urban certainly played a part in the formation of the working class in most parts of Africa in the 19th and 20th centuries-from migrant labour in the mines in southern Africa from the 1900s, to labour in oil extraction and processing in the Niger Delta from the 1970s. See Iliffe, 1983.

19: Davis, 2006, pp44-45.

20: See Morris, 1999.

21: Quoted in Ceruti, 2007, p22.

22: Classifying Soweto, research conducted by the CRS, Johannesburg, South Africa.

23: Ceruti, 2007, pp22-23.

24: Quoted in Ceruti, 2007, p20.

25: Quoted in Zeilig, 2002, p96.

26: See Renton, Seddon and Zeilig, 2007.

27: “Textiles No Longer Hanging By A Thread”, IRIN, 3 July 2006.

28: See “Madagascar: Outlook For 2007-08: Economic Growth”, the Economist Intelligence Unit, 7 March 2007.

29: But see Sautman and Hairong, forthcoming 2008.

30: See Sautman and Hairong, forthcoming 2007.

31: Christian Aid, 2007, p21.

32: See Larmer, 2006.

33: Christian Aid, 2007, p22.

34: Quoted in Sautman and Hairong, forthcoming 2008.

35: Davis, 2006, p161.

36: Walton and Seddon, 1994.

37: Zeilig and Seddon, 2002, p16.

38: Wiseman, 1996, p49.

39: See Renton, Seddon and Zeilig, 2007.

40: Interview with Brian Kagoro, 23 June 2003, Harare, Zimbabwe.

41: Mamdani, 1994, pp258-9.

42: Marx and Engels, 2003, p8.

43: “Swelling Cities Of The Global South”, Socialist Worker, 3 July 2007.

References

Bond, Patrick and Ashwin Desai, 2006, “Explaining Uneven and Combined Development in South Africa”, in Bill Dunn and Hugo Radice (eds), Permanent Revolution: Results and Prospects 100 Years On (Pluto).

Ceruti, Claire, 2007,”’Divisions and Dependencies among Working and Workless”, South African Labour Bulletin, volume 31, number 2.

Christian Aid, 2007, A Rich Seam: Who Benefits from Rising Commodity Prices (Christian Aid).

Davidson, Basil, 1992, The Black Man’s Burden: Africa and the Curse of the Nation–State (James Currey).

Davis, Mike, 2006, The Planet of Slums (Verso).

Harman, Chris, 2002, “The Workers of the World”, International Socialism 96 (autumn 2002), http://pubs.socialistreviewindex.org.uk/isj96/harman.htm

Harrison, Graham, 2002, Issues in the Contemporary Politics of Sub–Saharan Africa: the Dynamics of Struggle and Resistance (Palgrave).

Iliffe, John, 1983, The Emergence of African Capitalism (Macmillan).

Larmer, Miles, 2006, Mineworkers in Zambia: Labour and Political Change in Post_colonial Africa (Tauris Academic Studies).

Mamdani, Mahmood, 1994, “The Intelligentsia, the State and Social Movements in Africa” in Mamadou Diouf and Mahmood Mamdani (eds), Academic Freedom in Africa (CODESRIA).

Marx, Karl and Frederick Engels, 2003 [1848], The Communist Manifesto (Bookmarks).

Morris, Alan, 1999, Change and Continuity Survey of Soweto in the Late 1990s (University of the Witwatersrand).

Otieno, Gloria, 2006, Trade Liberalization and Poverty in Kenya: A Case Study of the Cotton Textiles Subsector (Kenya Institute for Public Policy Research and Analysis).

Quartey, Peter, 2006, “The Textile and Clothing Industry in Ghana”, in Herbert Rauch and Rudolph Traub-Merz (eds), The Future of the Textile and Clothing Industry in Sub–Saharan Africa (Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung).

Renton, David, David Seddon and Leo Zeilig, The Congo: Plunder and Resistance (Zed).

Sautman, Barry and Yan Hairong, forthcoming 2007, “Friends and Interests: China’s Distinctive Links with Africa”, African Studies Review, volume 50, number 3.

Sautman, Barry and Yan Hairong, forthcoming 2008, “The Forest for the Trees: Trade, Investment and the China-in-Africa Discourse”, Pacific Affairs, volume 81, number 1.

Seddon, David and Leo Zeilig, 2005, “Class and Protest in Africa: New Waves”, Review of African Political Economy 103.

Walton, John and David Seddon, 1994, Free Markets and Food Riots: the Politics of Global Adjustment (Blackwell).

Wiseman, John, 1996, The New Struggle for Democracy in Africa (Avebury).

Zeilig, Leo (ed), 2002, Class Struggle and Resistance in Africa (New Clarion).

Zeilig, Leo and David Seddon, 2002, “Marxism, Class and Resistance in Africa”, in Leo Zeilig (ed), Class Struggle and Resistance in Africa (New Clarion).

Zeilig, Leo, 2007, Revolt and Protest: Student Politics and Activism in sub–Saharan Africa (Tauris Academic Studies).