Scottish exceptionalism constantly pushes itself into the headlines. In 2014 the independence referendum came quite close to tearing the British state apart. The general election in 2015 saw the almost total wipeout of the Tories, Labour and the Lib Dems. These three “mainstream” parties gained just one seat each with the other 56 going to the Scottish National Party. In the 2016 European Union referendum the UK voted 52 to 48 percent to leave, including every English region apart from London. Scotland voted 62 to 38 percent to remain, with all 32 council areas backing this view.1 As we go to press the results of the 2017 UK general election show that Theresa May’s bid for a vote of confidence in the Tories has failed miserably across the UK. However, in Scotland the Tories have enjoyed a considerable advance, gaining 13 MPs. The last time they won more than a single Westminster MP was 1992.

But, despite the losses for the SNP in the most recent election, the differences between Scotland and the rest of the UK remain stark, and not just at the level of voting. Compare, for example, the SNP’s membership to that of Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour Party, by far the biggest UK political party in terms of membership. The SNP has 120,000 members, equivalent to 2.9 percent of the Scottish electorate. Across the UK Labour has 528,000 members or 1.1 percent of the electorate. In other words, in proportion the SNP is three times as big!2 Claiming to stand for the “nation” (ie everyone in Scotland), it has been able to attract supporters from the left and right, working class and upper class, and those in between. Even the SNP’s loss of popularity in a general election that has produced a hung parliament in Westminster still leaves it with 35 Scottish MPs compared to 24 for the other three parties combined.

One might expect such a sharp political disjuncture between Scotland and the UK to imply the inevitable break-up of Britain, but that is not the case. The shine has come off the SNP but the curious thing is that even when it was far stronger, there was a mismatch between its huge electoral support and backing for independence. In the 2014 referendum 55 percent voted to stay in the UK; the prospects of a different result in the near future are uncertain. When first minister Nicola Sturgeon announced her wish for a new independence referendum after the Brexit vote, and the SNP had 56 of 59 Scottish MPs, three different polls suggested majority support for continuing with the union at 52, 53 and 57 percent respectively.3 In the 19 polls conducted between June 2016 and April 2017 there was a majority for independence in only four (three of those being in the month Scotland voted against Brexit).4 For that reason the SNP carefully underplayed the issue of a second referendum in its 2017 general election campaign, placing that 10th in its list of 10 pledges.

The paradox is that, despite the very apparent political differences north and south of the border, the SNP cannot be sure of winning a referendum on grounds that these differences justify independence. This discrepancy is not new. When the annual British Social Attitudes survey asked Scots how they self-identified in 2013 it transpired that “only around one in five say that they are British, while typically around three-quarters or so indicate they are Scottish”.5 Yet the BSA also found:

There is certainly no evidence that the electoral success of the SNP in 2007 and 2011, success that led to the decision to hold a referendum on independence, was occasioned by an increased in support for leaving the UK. In fact, if anything the opposite is the case. Between 1999 and 2006 support for independence averaged 30 percent; since the SNP first came to power in 2007 it has averaged 26 percent.6

So “the correspondence between identity and preference is far from perfect”,7 the key point being that if support for the SNP is not due to its central policy of independence, the marked political differences between Scotland and the UK must, to a great extent, be motivated by something else. This conclusion flies in the face of common sense assumptions. The Tories explain their success in June 2017 as due to campaigning against indyref2. Kezia Dugdale, the Scottish Labour leader, puts Labour’s increase from one to seven MPs down to precisely the same reason. So is it not the case that Scottish political exceptionalism is due to the national question?

This article will argue that the opposite is true. What most commentators perceive as a political climate primarily moulded by the national issue actually reflects class concerns refracted through a nationalist lens. To substantiate this claim and identify the motor driving Scottish politics requires investigation of the complex interaction between nationalism and class, economic base and state superstructure.

Divergence and convergence: Scotland in the UK

The first question to ask is whether Scotland’s distinct political trajectory is engendered by a basic material contrast with the rest of the UK.

Before the industrial revolution agriculture dominated the economy north and south of the border. The industrial revolution broke this commonality. Scotland’s geography and natural resources, such as deep rivers and abundant coal and iron ore supplies, encouraged a focus on heavy industry, whereas industry in England was more diverse. In 1907 42 percent of Scottish production came from mining, iron, steel, engineering and shipbuilding compared to 30 percent in the UK overall.8 Recently, however, that distinction has disappeared. As one writer put it in 1996: “In the last three decades, Scotland’s industrial structure has come to resemble that of Great Britain as a whole”.9 Decline in manufacturing compared to service industries has been greatest north of the border. Scotland now lies below the UK average in terms of the percentage employed in manufacturing, with only London and the South East lower.10

Another example of a change from divergence to convergence is housing. In Scotland rapid Victorian industrialisation (and consequent urbanisation) combined with greater levels of poverty wages to generate appalling housing conditions. In the 1900s nine of the 15 most expensive local authority areas in the UK in terms of rent were Scottish. Around this time the rate of evictions for non-payment of rent in Glasgow was 34 times higher than in London.11 The famous Glasgow rent strike of 1915 was no fluke. However, by 2015 Scotland’s housing costs were no longer exceptional. Within the UK “the North-South gap has subsequently narrowed across most regions”.12

Wealth is a further indicator of trends. Historically the predominance of heavy industry (with consequently fewer white collar workers, restricted female job opportunities and high housing costs) contributed to a situation of relative poverty in Scotland, the average level of income being considerably lower than in the UK overall.13 Today Scotland is less distinct. In terms of gross domestic household income it is fifth out of the 12 UK regions. By 2014 gross disposable household income per head in Scotland was £17,095, close to the UK average of £17,965.14

This is not to say that there are no differences between Scotland and the rest of the UK, so convergence should not be exaggerated. Median household total wealth in Scotland along with the North of England is lower than the South East of England (the difference is probably largely attributable to house prices).15 Life expectancy for a female child born in Scotland now is 80.8 years compared to 82.9 years in England. For males the figures are 76.6 and 78.9 respectively. And Scotland remains the worst of all UK regions in terms of health.16

Moreover, Scotland has some distinct institutions (the law, education and the established church), while devolution has recently created more differences (in student fees, top income tax rates, elderly social care, etc). At present, however, these factors remain peripheral in much the same way as there are institutional differences between London and other regions of England.

Therefore the increasing political gap between Scotland and the rest of the UK cannot be explained by large underlying differences in material circumstances. The matter has to be posed in a different way.

Radical Scotland?

Could it be that in each country broad social attitudes are moving in different directions and this relative shift is driving high politics? The 2011-12 British Social Attitudes survey explored this factor. It found “opinion in both countries has moved in a somewhat less social democratic direction”.17 The BSA asked whether Scots were keener than the English on redistribution of income from the better-off to those less well off. The answer to this was “Yes” (43 percent agreed; 26 percent disagreed); but between 2000 and 2010, as the SNP marched forward electorally, the difference between Scotland and England on this question actually declined—from 12 percent to 9 percent.18 Many such areas of potential divergence were investigated but the pattern proved consistent: “Despite the differences in their politics…the two countries continue to bring much the same outlook to many of the key questions that confront governments today”.19

Nonetheless, the BSA authors do find that “people in Scotland are generally a little more likely than those in England to express social democratic views”.20 This opens a second possibility: that in absolute terms there is a decisive difference between opinions north and south. That would only hold if Scotland is compared to England (or the UK) as a whole. But these are not homogeneous units. When Scotland is directly compared to regions sharing similar material circumstances differences in attitudes also tend to disappear. Areas such as Wales and the North West and North East of England have comparable economic histories and contemporary economic structures.

Writing in the early 2000s about the economic, employment and social characteristics of Scotland (before the SNP’s great electoral advance) Gregor Gall concludes:

In terms of social-group and social-class segmentation, Scotland appears more working class and less middle class than Britain as a whole. However, it is unlikely that compared to other similar regions such as the north of England and Wales, this would remain significant… In terms of unemployment and economic restructuring, the experience in Scotland has not been significantly worse than that in other comparable regions in the rest of Britain.21

Gall draws the same conclusion in regard to other aspects such as the belief that workers and their unions in Scotland “are more ‘militant’ and ‘radical’ in industrial, political and social terms than their counterparts in the rest of Britain”. The data support this view when comparing Scotland against England and Wales as undifferentiated single units:

If, however, Scotland as a unit of analysis is compared to other regions of Britain, it is more strike prone and so on than a number of regions such as South West and South East England and the east Midlands. But it is not any more so compared with Wales and North West and North East England.22

It does not follow that class struggles and their outcomes have necessarily been identical north and south. Institutional differences such as devolution can make a difference. For example, the application of the poll tax to Scotland before the rest of the UK presented an opportunity for a campaign led by Tommy Sheridan that gained great prominence. When this was later combined with the establishment of the Scottish Parliament (using proportional representation) Sheridan’s Scottish Socialist Party was able to win six seats. Although the poll tax campaign became a UK-wide phenomenon culminating in the 1990 riot in London that led to Margaret Thatcher’s eventual downfall, no equivalent parliamentary breakthrough occurred at Westminster. More recently the bedroom tax has been vigorously opposed both north and south, but only in Scotland has the campaign been able to win its abolition, through the SNP government in 2015. Over time the impact of devolution on institutions like the NHS, or different outcomes in struggles and so on, might gradually prise open a real space between Scotland and the rest of the UK; but as the economic and BSA evidence shows, to date these factors are still marginal. The outcome of the 2017 general election, which has seen a recovery of UK-wide parties at the expense of the SNP, has underlined that, despite undoubted Scottish exceptionalism, in the political sphere the ties to UK politics have not been entirely severed.

If Scots are “a little more likely…to express social democratic views” than the English, in general this is due to the relatively greater concentration at the aggregate level (Scotland versus England treated as single units) of those who struggle to survive poverty, exploitation, declining services, stress at work and so on, under capitalism—in short the experience of class rather than nation. That is not the judgement of the majority of bourgeois analysts or, unfortunately, some left wing thinkers who tend to fudge class and nation, painting Scotland as inherently red.

The paradox in operation

It would be foolish to deny that national ideology plays some role. Nationalism stimulated the formation of the SNP, gives it a raison d’être and is the key motivator for a certain proportion of its voters. Labour’s wipeout at the 2015 general election was linked to its opposition to independence (though, as Keir McKechnie has argued, support for a Yes vote rested above all on class identification of independence with anti-austerity23).

The difficulty of ascertaining political cause and effect arises from the institutional structures of bourgeois democracy. They are geographically based and, unlike bodies such as trade unions and class-based parties, deliberately obscure class. So signals from Scottish elections to Holyrood or Westminster can give the impression that the desire for constitutional change is the major determinant, rather than the social aspirations that underlie much electoral behaviour. Careful analysis is therefore needed to discover the real processes at work. The outcomes of the 2014 Scottish independence and the 2016 European Union referendums, both analysed in this journal, confirm the general argument presented here.

In formal terms the 2014 referendum was to decide on Scottish independence but:

The two most important issues for Yes voters were the economy and defending the National Health Service… The Yes vote was a verdict on neoliberal Britain… As Financial Times journalists John Burn-Murdoch and Aleksandra Wisniewska point out, “the No vote tended to fall as the proportion of people receiving unemployment or disability related benefit rose, supporting the narrative that perceived social injustice was one of the driving forces behind the Yes vote”.24

Scotland’s vote in the EU referendum could be taken to signify a rupture along national lines. However, the same class features lay behind the No vote in the EU referendum in both Scotland and the UK: “The more affluent were more likely to vote Remain and poorer people were more likely to vote Leave… The correlation is much weaker than in England and Wales but nonetheless the vote in Scotland can be seen as ‘a revolt against the establishment’ particularly in poorer areas”.25

Understanding the peculiarity of Scottish voting behaviour as shaped by class dressed in constitutional garb leads to a couple of related questions: why is nationalism not the key driver? And why has a nationalist party nevertheless reaped major electoral benefits?

To answer the first: nationalism, which identifies a common cross-class interest among people living in a state (or a putative state), can be divided into two types. One is reactionary nationalism in which the masses of the population more or less uncritically take on the views of their local capitalist class in its competitive struggle against other ruling classes. This version is all too common today and has contributed to the electoral success of Donald Trump, for example. It acquires its strength from the fact that, as Karl Marx put it: “The ideas of the ruling class are in every epoch the ruling ideas”.26

The other type of nationalism is that of oppressed countries (“progressive nationalism”). However unequally all classes within the nation suffer from external oppression there is a genuine, if limited and temporary, alignment of interests in throwing off the shackles. The local ruling class may want to expand its freedom to exploit while the working class may want freedom from foreign exploitation, but both want freedom. Anti-colonial struggles were typical examples. This nationalism derives its strength by harnessing the energy of the masses who fight for an element of their own interests in a programme of national liberation shared with “their” capitalists.

Neither type of nationalism is prominent in Scotland today. Reactionary nationalism is weak north of the border because the Scottish ruling class is itself divided on whether it is best to compete as a separate country or as part of the larger UK. The pro-independence grouping therefore cannot present a coherent or united set of “ruling ideas” to pull the mass of people behind capital’s ambitions. Instead its actual expression is a composite of nationalist leadership combined with a social democratic appeal to voters.

Neither is Scotland an oppressed nation. Indeed it once played an important, if junior, oppressive role in the days of the British Empire. Therefore, Scottish nationalism dare not call upon popular class aspirations to be free of an external enemy in the same way as has been seen in Ireland, South Africa or Palestine. Rather than workers directing their anger against “English national oppression” they resent their exploitation as workers, but to give vent to this anger is potentially inimical to Scottish capitalism. This was shown during the 2014 referendum campaign when the then SNP leader Alex Salmond briefly toyed with radical anti-austerity rhetoric during a TV debate. Support for independence pulled into the lead in the opinion polls, but Salmond immediately backed away into safer constitutional territory afterwards and the lead was lost.

The second question, about why the SNP has been electorally successful, connects events in Scotland to much wider political currents. The slightly greater preponderance of social democratic attitudes in Scotland compared to the UK overall formerly benefitted the Scottish Labour Party. If this article had been written as recently as 2010 almost exactly the same words now applied to the SNP’s political dominance could have been used to describe Labour’s position.

However, social democratic parties are in deep crisis. They find it increasingly difficult simultaneously to straddle the interests of capitalism and their working class supporters, usually opting to represent the former. This creates a void that can be filled by others—and when this happens the consequences can be terminal. In 2004 the social democratic party Pasok took 44 percent of the Greek vote; a decade later it took just 5 percent, having lost its voting base to Syriza. In France the Socialist Party candidate for president received 6.2 percent of the vote in 2017. During the first and second rounds of the 2012 election their candidate, François Hollande, gained 29 percent and 52 percent respectively.

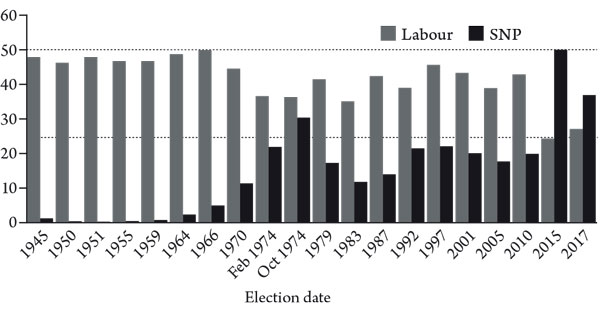

In Scotland, Labour’s displacement, as evidenced by its share of the vote, has been equally spectacular (figure 1). Labour’s strength over many decades meant that even when not in government at UK level it was in government locally. Therefore, when the crisis of capitalism developed, the cuts and austerity that followed were administered by Labour against its own Scottish voting base. South of the border Labour remains the only serious electoral alternative to the Tories (who are even more strongly associated with cuts and austerity) so it has thus far escaped electoral annihilation, and with Corbyn recovered much lost ground.

Figure 1: Labour Party/SNP share of the vote in Scotland, UK general elections since 1945 (percentage).

Source: UK Election Statistics, 2016; BBC News, 2017.

The border gave the SNP a framework to steal Labour’s social democratic mantle in a way not open in similar English regions. Such a development was not inevitable. The neutrality of Scottish nationalism (vis-a-vis reactionary and progressive forms) gave the SNP leadership a choice about how to displace its main electoral rival. When Salmond succeeded John Swinney as leader in 2004 he consciously chose to tack left, declaring that “independence is our idea, our politics are social democrat”.27 The decision was helped by the Tories’ weakness (many voters had already been won to the SNP once they became the only tactical voting alternative to Labour) and because “Scotland has been losing population in relative and absolute terms”28 for decades, making the racist card less attractive.

The SNP’s social democratic credentials are impeccable (both in strengths and weaknesses). The 2016 and 2017 manifestoes combined impressive promises on welfare with a commitment to make Scotland “a competitive place to do business”.29 In some respects what Lenin said about the nature of the British Labour Party also applies to the SNP:

Most of the Labour Party’s members are workingmen. However, whether or not a party is really a political party of the workers does not depend solely upon a membership of workers, but also upon the men that lead it, and the content of its actions and its political tactics. Only this latter determines whether we really have before us a political party of the proletariat.30

However, in other ways the SNP differs significantly from Labour. Though, as the above quote shows, social composition is not in itself the determinant of a party’s character, it is an influence on its behaviour. For example, the acquiescence of trade union leaders has played an important role in Corbyn’s ability to survive the general hostility of the Parliamentary Labour Party. The SNP has no such relationship to the organised working class, even though its Trade Union Group, with a membership of around 16,000, actually outnumbers the total membership of Scottish Labour (which is some 10,000 to 13,000). The backgrounds of the crop of MPs elected in 2015 are revealing (see table 1).

Table 1: Main former occupations of MPs elected in 2015 (percentage)

Source: UK Election Statistics: 1918-2016.31

|

|

Labour |

SNP |

Conservative |

|

Business |

11 |

34 |

44 |

|

Professions |

15 |

20 |

30 |

|

White collar and manual |

61 |

34 |

21 |

|

Manual workers only |

9 |

0 |

1 |

The SNP’s lack of an organic connection to the working class means that its adoption of social democratic rhetoric is superficial and could be overthrown as easily as it was adopted. Though it benefits from working class membership and votes, the guiding light for the SNP leadership remains constitutional change within the framework of the bourgeois state. While capitalism exists, the daily experience of the majority is pressure on living standards, stress and bullying at work, and cuts in vital social services. The disaffection generated has converted into a period of increased votes for the SNP (as it previously fed into votes for Labour). But it was not nationalism that lay behind the phenomenon.

Furthermore, the party faces the same contradictions that afflicted its more conventional social democratic predecessor. For all its anti-austerity rhetoric it has presided over major council cuts, has run into conflict with rail unions, council workers and college lecturers, and it has allowed the boss of Ineos at Grangemouth oil refinery to break union organisation. For a time the party could lay all the blame on “Westminster”, but austerity excused is still austerity and this truth is beginning to dawn on some supporters. Dugdale has claimed that her aping of Tory anti-independence rhetoric lies behind Labour partial recovery at the 2017 election. However, contrary to her claims, a recent analysis by John Curtice, “The Labour Surge Washes over Hadrian’s Wall”, suggests that it is Corbyn’s campaign that has turned the tide.32

The worldwide spike in acute alienation from the current political set-up (following the recent economic crisis) has occurred across Britain, and from this angle it is legitimate to see part of the SNP’s electoral support as representing a break from established mainstream parties to the left, in the same way that UKIP attracted this from the right in other parts of the UK. To the question “Which party captured the protest vote in Scotland?” there is an obvious answer. Whereas UKIP gained 12.6 percent of the UK vote in 2015 its share in the 2007, 2011 and 2016 Scottish parliamentary elections was 0.4 percent, 0.91 percent and 2 percent respectively. The SNP stifled the growth of UKIP as a magnet for protest votes, and despite Labour’s modest gains in the 2017 general election it has muted the impact of Corbynism.

Evidently, the recent peculiarity of Scottish politics has been less due to a desire for constitutional change than Labour’s historic decline as the channel for popular discontent. However, the situation is not static and the impact of the 2014 referendum campaign (much of it conducted on an independent left basis—for anti-austerity, anti-Trident and redistributive policies) remains in evidence. The 2017 Scottish Social Attitudes report provides a more up to date picture:

As recently as 2012, as few as 23 percent chose independence as their preferred constitutional option. [Now] twice as many (46 percent) backed independence…the September 2014 independence referendum left an important long-term legacy—a much higher level of support for independence than ever before.33

There is now also a closer alignment between voting SNP and supporting independence:

Back in 2001, just 35 percent of those who then supported independence voted for the SNP in that year’s UK general election. Even in 2010 the figure still stood at no more than 55 percent. But in the 2015 contest, in which the SNP secured 56 of Scotland’s 59 seats, no less than 85 percent did so… In short, on both sides of the argument how people vote at election time now matches more closely their views on the independence question.34

Does this mean that what is written above about class has been overtaken or replaced by nationalism post-2014? And would majority support for independence nullify the paradox? Not at all, since the question concerns both what motivates people in the first place and the separate matter of how that is expressed. This can be demonstrated in two ways—the council elections and the EU referendum.

Raymie Kiernan’s unpublished analysis of May 2017’s council election results shows that although the Tories gained seats (largely at the expense of Labour), the SNP’s electoral domination continues:

Now the SNP is the largest party in over half of Scotland’s 32 local authorities. Over recent years the SNP’s base of support has grown in working class areas, particularly across the central belt, but consequently declined in its traditional, more rural former Tory voting areas. The more densely populated, working class poorer urbanised areas of the central belt have been the source of the SNP’s remarkable growth.35

However, there are also signs of the danger that besets all social democratic parties—winning votes by talking left but managing rather than challenging capitalism and so ultimately disappointing the electorate. In the 12 council areas that voted above average for independence in 2014: “Four saw the SNP lose seats—in three of these the party was responsible for cuts”. The effect was even more striking in the 17 council areas that voted above average against independence: “Ten saw the SNP suffer losses. In nine of them the party had been running the council either as a majority or as part of a coalition making cuts”. The council election results clearly prefigured the general election, though the Corbyn bounce was absent in them.

The EU issue is another complication for the SNP. The British ruling class may be divided on Remain or Leave; but that section of the Scottish ruling class backing independence is not, and cannot be, so divided. For Scotland to cast adrift from the UK and launch successfully into the world competition of capitalisms it needs the EU, particularly after the collapse of oil revenues.

However, as demonstrated above, a working class rejection of EU membership exists in Scotland if in attenuated form. Scottish Social Attitudes reports that “one in three (33 percent) of those who say they would now vote Yes to independence report that they voted last June to Leave”:

Despite the 62 percent vote in favour of remaining in the EU, Scotland is now more Eurosceptic than at any time since the advent of devolution. Back in 2000 just 38 percent of people in Scotland said that Britain should either leave the EU (11 percent) or should remain a member but try to reduce the EU’s powers (27 percent). Almost as many (31 percent) actually wanted the EU to become more powerful. Now, however, no less than two in three are sceptical about the EU, with 25 percent saying that Britain should leave and no less than 42 percent that it should try to reduce the EU’s powers.36

Commenting on these results, John Curtice concludes that “banging on about Europe” may not win the numbers needed to secure Yes in a Scottish independence referendum. So the paradox has reared its head once again. The class element has tended to reinforce the SNP’s election results, but works against its pro-capitalist stance on the EU, the party’s justification for an independence referendum!

Conclusion

What does the above analysis mean for revolutionary socialists? First, the crisis of social democracy infects both its electoral base and its ideological coherence. That has an impact on how the “Scottish question” is interpreted. For almost a century and a half a Marxist vocabulary of class, nation, oppression, etc was common ground on the left, and even survived the split between reformism and revolution that followed the Bolshevik victory. Today that shared language has gone, making analysis more opaque for both participants and onlookers. It requires consistent and rigorous use of Marxist categories—in this case class and nation—to find a way through complex social phenomena such as we are witnessing in Scotland.

Second, insofar as there is a convergence of many aspects of Scottish and British society overall, we continue to face issues such as racism, sexism, low levels of collective class struggle and austerity north and south of the border. This is irrespective of constitutional arrangements. The 2014 referendum was an extraordinary event. The turnout of 85 percent was the highest since the inception of universal suffrage in the UK. There were giant “Yes” mass meetings and marches led by forces to the left of the SNP. This mood still exists. Just days before the 2017 election, when the SNP was deliberately downplaying indyref2, some 20,000 took part in the “All Under One Banner” march for independence in Glasgow. Yet the impact of the independence campaign on the long-term fortunes of the left has been relatively shallow because even with this level of engagement voting is quite a passive activity. Any new independence referendum should not become a distraction from, or an excuse to avoid grassroots battles north and south.

Third, as the above analysis suggests, class issues are not tangential to increasing support for a Yes vote, but are the key to it. The support for independence that arises from the peculiarity of Scottish politics (class concerns expressed in nationalist clothing) has not gone away, even if the social and economic foundations are similar north and south. We must relate to this fact, but our motivation in supporting a second Scottish independence referendum is to break up the British state and weaken British nationalism, which plays a reactionary role at home and worldwide. We will not argue for establishing a small capitalist state north of the border as part of a larger European coalition of capitalist states, as this would not be a significant advantage to ordinary Scottish people. The benefits of Scottish independence would be bestowed on the British working class and opponents of imperialism everywhere.

Donny Gluckstein is a member of Edinburgh SWP and a trade union activist in the EIS.

Notes

1 McKinnon and Gluckstein, 2017, p175.

2 House of Commons Library, 2017.

3 Opinion polls from 15 March, 8-13 March and 9-14 March 2017 quoted in Kirk, 2017, and BBC News, 2017.

4 ScotCen, 2017.

5 NatCen, 2013, p144.

6 NatCen, 2013, p156.

7 NatCen, 2013, p159.

8 Lee, 1995, p28.

9 Payne, P, quoted in Gall, 2005, p89.

10 Rhodes, 2015, figures are for 2014.

11 Lee, 1995, p46.

12 Clarke, Corlett and Judge, 2016, p23.

13 Lee, 1995, pp36-38.

14 Office for National Statistics, 2016.

15 Office for National Statistics, 2014, pp12-13.

16 Office for National Statistics, 2015.

17 NatCen, 2012, p21.

18 NatCen, 2012, p27.

19 NatCen, 2012, p34.

20 NatCen, 2012, p21.

21 Gall, 2005, pp108-109.

22 Gall, 2005, pp176-177.

23 McKechnie, 2014.

24 McKechnie, 2014, p7.

25 McKinnon and Gluckstein, 2017, p178.

26 Marx, 1845.

27 McKechnie, 2013, p10.

28 Paterson, Bechofer and McCrone, 2004, p10.

29 Scottish National Party, 2016, p13.

30 Quoted in Cliff and Gluckstein, 1996, pp1-2.

31 The categories used in this House of Commons report are rather arbitrary as teachers, civil servants and local government workers are included under “professions”, while “white collar” includes political organisers, publishers and journalists. Nevertheless the overall pattern in terms of social composition is clear enough.

32 Curtice, 2017b.

33 Scottish Social Attitudes survey 2017 quoted in Curtice, 2017a.

34 Scottish Social Attitudes survey 2017 quoted in Curtice, 2017a.

35 Personal communication by email.

36 Scottish Social Attitudes survey 2017 quoted in Curtice, 2017a.

References