A row over racist abuse on the January 2007 edition of Celebrity Big Brother focused public attention in the UK on ‘reality TV’. This round of public outrage is merely the latest in a long series of disputes that have dogged Big Brother since the first version was broadcast in the Netherlands in 1999.

Controversy over the show is not confined to racism. Figures from across the spectrum of opinion have debated the morals of the contestants, and the morality of watching them in situations usually regarded as private and personal.1 In fact, the very idea of the show initially struck its eventual British promoter, Peter Bazalgette, as too shocking. Writing to the programme’s Dutch inventor, John de Mol, he rejected the idea, arguing:

The rats-in-a-cage-who’ll-do-anything-for-money is something that I doubt we could sell on to commercial television…as currently constituted, we feel the show has a narrow market in the UK.2

The storms over the show and the free publicity they generate in the media are a big factor in its success or failure. The format of locking people into a confined space together for several weeks is more or less bound to generate conflict of one kind or another. There are, however, much wider issues about the nature of cultural experience in contemporary capitalism that are involved in this kind of broadcasting. The various manifestations of Big Brother are one version of the broader category of ‘reality TV’ that has a central place in contemporary television.

What is ‘reality TV’ and why is there so much of it around?

The kinds of programmes known as ‘reality TV’ form a very mixed bag. They include what are essentially game shows, such as Big Brother, ‘docusoaps’ such as Airport and ‘true crime’ shows such as Crimewatch UK. The popularity of such programmes is located in the shifting economics of broadcasting, which involves increasing competition and a move from the search for a mass audience to a niche audience. Television began as a technology that could only sustain a small number of channels. The imperative was to try to attract the largest possible number of people to a channel, and programme types such as the soap opera, the situation comedy and the variety show were developed precisely to generate this ‘mass’ audience.

Few channels meant little competition for revenue. In the UK the main commercial broadcasters, the consortium of companies making up ITV, enjoyed a monopoly of the sale of television advertising on terrestrial TV from its inception in 1955 right up to 1993. To the extent that ITV faced competition from the BBC, it was for audiences, not revenues.3 In the course of the 1970s and 1980s a combination of technical changes and shifts of government policy started to undermine the mass audience. The increasing penetration of cable and satellite delivery systems meant that multichannel television became a reality, first in the US and later in Europe. At the same time, particularly in Europe, neoliberal ideology increasingly favoured competition and markets as against the combination of political and cultural paternalism that had dominated the main national broadcasting organisations.

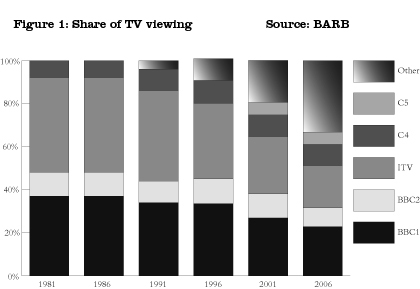

Established broadcasters found themselves faced with a new situation (see

figure 1). On the one hand, they were, and are, still the only people who can deliver anything approaching a mass audience: ITV’s drop from 44 percent audience share in 1981 to 20 percent in 2006 may be a drastic decline on the past, but it is still ten times as great as the most successful of the niche channels. On the other hand, they no longer enjoyed a more or less captive audience—some viewers spent more of their time watching channels that provided a diet of programmes more exactly suited to their narrow range of tastes. The mainstream broadcasters thus needed to develop programmes that could both attract as much of the mass audience as possible and find ways of holding on to hard to reach groups such as young people.

The traditional terrestrial channels responded to the new challenges with a range of strategies. The first was very traditional—they launched an attack on the conditions of the workers who produce television programmes. One major mechanism for this was to move from predominantly in-house production to subcontracting production to independent companies. For many workers, this meant a shift from permanent, full-time, and highly organised, employment to a succession of short-term contracts under much worse conditions.4 Another was to try to find new programme types that could still gather a mass audience but which were much less expensive than the traditional formats. A third was to try to minimise the risks of investing heavily in failure, for instance by making new programmes that are quite like old programmes that were a hit or by reusing a format that has succeeded in another broadcasting market.5 The fourth important mechanism was to try to commercialise programmes more fully, for example by pushing associated merchandise such as books and DVDs, and using the same material across different platforms. A fifth was to try to develop programme types that appealed to particularly desirable audience segments.

It was this combination of factors that led to the rise of the wide variety of reality TV shows. Such shows are relatively cheap, and some are very cheap indeed. There is no need to pay writers or actors, no endless rehearsals, no need for elaborate sets, no need for rights clearance for music, and so on. Using ‘ordinary’ people, and later minor and declining celebrities, is a cheap way to make television:

Reality programming provides a cheap alternative to drama. Typically, an hour-long drama can cost approximately $1.5m (£875,000) per hour, whereas reality programmes can cost as little as $200,000 (£114,000) per hour.6

The flood of ‘documentary’ films about passing a driving test, working in the air transport industry, looking after animals, and the flood of makeover programmes about houses, clothes and body shape, all fit this economic dynamic exactly. Big Brother and Survivor, which has fulfilled the same function in the US, evolve out of these conditions. In many respects they displayed all of the characteristics of the type, but they differ slightly from the bog-standard reality show in some important respects. In neither the UK nor the US were the broadcasters taking big risks. Both of the programmes are based on formats that had been tested in other markets but then modified to take account of the particularities of different national audiences. Big Brother was originally shown in the Netherlands and, despite Bazalgette’s worries, it proved a successful formula.7 It was taken up widely as a proven crowd puller by broadcasters around the globe.8

These programmes also originated with independent production companies, which meant the broadcasters did not have to bear the development costs. This independent origin is, however, something of a double-edged sword. The great success of the format has meant that Endemol, the Netherlands company that originated Big Brother, has been able to strike hard bargains with broadcasters wishing to buy it.

This leads to one of the major differences between these shows and the standard reality television product—they are relatively expensive. Quite apart from the cost of purchasing the rights to such a successful show, Big Brother has other large expenses. Continuous surveillance of contestants requires a production team of about ‘200 people…including 50 cameramen [sic] and 13 producers’.9 Celebrity Big Brother has the additional cost that, while the celebrities are not exactly A-list, they still expect substantial fees. Shilpa Shetty was allegedly paid somewhere between £200,000 and £300,000 simply for appearing in the show.10 Survivor, which uses exotic locations and is produced up to the standards of primetime US network TV, is also extremely costly for a reality programme. The justification for this expense is that these programmes deliver extremely valuable audiences, which in turn earns broadcasters very large advertising fees. Hill writes of Big Brother:

Big Brother gave Channel 4 its most popular ratings in the history of the UK channel, attracting nearly 10 million viewers in 2000; the second series of Big Brother averaged 4.5 million viewers, giving Channel 4 more than a 70 per cent increase on their average broadcast share. Big Brother 3 generated over 10 million text messages, and attracted 10 million viewers for its finale. A 30 second advertising spot during Big Brother 3 cost £40,000, over three times more than for any other show on Channel 4 in 2003 (for example, Frasier’s cash value was £14,000 for a 30 second spot).11

Really real?

The label ‘reality TV’ begs the question, ‘How real is what we see?’ The answer, of course, is, ‘Not at all.’ These programmes make a strong claim to some form of ‘realism’. This is sustained by the style in which such programmes are usually shot, which clearly originated in the genre of observational documentary, which does make strong claims to reveal reality. A further dimension of ‘realism’ is added by the fact that the contestants are usually not professional actors and they are usually seen in unscripted and mundane situations. In fact, these are rhetorical rather than substantial features of such programmes; what we see is a highly-constructed artefact rather than a slice of ‘real life’.

The process of manipulation begins long before the shooting starts. The selection of contestants is the first hurdle. In Celebrity Big Brother, and similar shows, there is no pretence that the people are anything other than extraordinary. Unlike their more plebeian fellows, they are well paid for their time. ‘Ordinary’ contestants get a fee to cover expenses—for these contestants, a major motive often seems to be a desire to become a celebrity and to work in television. Certainly some people, Jade Goody for example, have seen their lives transformed by success. From the first UK series, winner Craig Phillips, runner-up Anna Nolan, and villain ‘Nasty’ Nick Bateman have all had reasonably successful careers in the media. This is not an invariable outcome, however. Nichola Holt, also from the first series, had some initial media success but eventually landed in much less glamorous circumstances.

The participants in the non-celebrity shows are presented to us as a cross-section of ‘ordinary’ people reflecting contemporary British society, or at least its younger, European members.12 In fact, the people we get to see are the product of an elaborate process of selection in which the producers choose a group that they hope will produce good television. As Bazalgette puts it, ‘There are three crucial factors in the production of Big Brother: casting, casting and casting’.13

For the earlier series, the process began with a flood (usually more than 100,000 each time) of expressions of interest, and the filling in of an elaborate form. Motivated individuals who survived that sent in two-minute videotapes. There were about 5,000 for the second series, 9,166 for the third, and 10,012 for the fourth.14 The process of selection for the 2007 show, which closed in February, was rather simpler, which may reflect reduced public interest.15 As the selection proceeds, candidates are interviewed, by a psychotherapist among other people. Eventually, a small number of participants and reserves are chosen.16

At least for the earlier series, the producers denied casting for open conflict, and specifically they denied they cast for explicit racial or sexual conflict. The psychotherapist for the first series argued that it would be counter-productive to ‘throw in people who would obviously disagree, like putting a racist and black guy together…we know opposites like that would have a big fight and then stop communicating, and in the house they had to keep communicating for a long time’.17 What they are certainly looking for are characters who can be expected to develop complex relationships and thus ongoing dramas. The producers are also prepared to manipulate the contestants to achieve this, rather than simply relying on events to take their natural course. The contrived nature of the environment, with many of the determinants (eg work) and distractions (eg television) that characterise our everyday lives removed, acts strongly to prioritise personal interactions based upon taste and interest. This probability is intensified through the interventions of the disembodied Big Brother himself and the tasks set for the participants.

In order to achieve dramatic narratives, the producers ruthlessly edit the raw footage. For example, in the first Australian series 182,750 hours of material were edited down to 70 hours of television.18 An extreme ‘observational’ documentarist like Roger Graef might have a shooting ratio of 30 to one, and a drama perhaps three to one; the Australian Big Brother figures work out at 1,565 to one. Even the ‘live’ show broadcast continuously (first on the web and then on E4 in the UK) is not an unmediated account of reality but an edited selection of shots (there are no ‘action’ shots from the camera in the toilet, thankfully). More importantly, it is not live: there is a built-in delay of ten minutes to allow for editorial intervention in the case of unsuitable material, for example, brand advertising, swearing, defamatory material and ‘inappropriate behaviour’. This resource is used. Bazalgette records an incident involving Jade Goody from her first appearance which provoked a long debate among the production team and heavy censorship in the great British tradition of prudery.19 More recently, police investigations into charges of racism have focused on tapes allegedly containing more offensive material that were not broadcast.

Just as much as anything else on television, Big Brother is constructed to attract and hold an audience which will, in a commercial context, be sold to the highest bidder. It uses ‘real’ people in certain kinds of ‘real’ situations, but it chooses and manipulates them in order to produce narrative, drama and conflict.

The evolution of the form

Not all series of Big Brother have been equally successful. The indications are that the first three series played to average audiences that increased from 4.6 million to 5.9 million.20 Between versions three and four, however, Channel 4 issued advice on ‘how not to get into Big Brother’, the prospective contestants’ tapes contained less extreme behaviour, and the casting appears to have been designed to provoke less dramatic conflicts.21 The series was rewarded with a slump in ratings to 4.9 million and the producers thought again. What they thought was that they needed to make the show more sensational in order to recover the audience, and both casting and editorial interventions became more extreme. This reversed the decline in ratings, but in order to maintain interest there has been an obligation to ratchet up the eccentricity of the cast of characters and the unpleasantness of the tasks they must perform. As the Creative Director of Big Brother argued, ‘The levels of intervention from us increase as the show progresses—we have to find creative ways of making the experience different’.22 In pursuit of this objective, the ‘character’ of Big Brother has changed over the years, becoming crueller and more demanding. The BBC reported at the start of the 2006 series, ‘Big Brother will be “more twisted than ever” this year, according to the Channel 4 reality show’s producers’.23

The British production team continue to reject the frequent charge that they are casting specifically for sexual encounters, although they recognise that there is likely to be at least some of the latter.24 As Bazalgette put it:

Put twelve young people in a confined space for a length of time and there will be both sexual tensions and releases. But to succeed Big Brother needs relationships to develop. Sex is incidental—Big Brother remained popular in the US, Australia and the UK for several series without any instances of sexual intercourse.25

Some conflict, and some crises, and some romances are valuable elements in developing the kind of narrative that ‘good television’ requires in order to attract a large audience, but these elements must appear to us to arise out of the dynamics of the household.

The development of the form, however, has changed those dynamics. In reality, the show has moved away from its always tenuous claims on ‘reality’ and more towards performance. The casting and the situations are more and more contrived to allow the participants to display themselves in situations ranging from the undignified to the grotesque. In this, the standard Big Brother has converged more and more closely with Celebrity Big Brother, where the casting of entertainment professionals always meant that a high degree of performance would be central to the show. Jade Goody, who was the star, if not the winner, of the standard series she participated in (Big Brother _3_ back in 2002) exemplifies this shift towards the self-conscious performance for the cameras.

The producers of the recent series of Celebrity Big Brother might not have known and agreed in advance that the mix of personalities they chose was going to result in racist bullying and abuse, but they certainly knew that it contained all of the elements of a first rate row and this would be very good for ratings. Good for ratings is good for business: Endemol’s share price rose sharply after the recent row.26

Who watches this stuff, and what sense do they make of it?

All of the series of Big Brother, even the ‘boring’ fourth series, and all of the celebrity versions as well, have played to audiences that are quite substantial for contemporary British television. They are not the highest rated programmes: as figure 2 demonstrates, those spots are held, week in week out, by the primetime soaps. To compare the Big Brother audience with that of the soaps, however, is slightly misleading. While the soaps air early in the evening, Big Brother is broadcast much later, when the available audience is smaller. In its late evening slot, Big Brother often has the largest audience share. As is also clear from figure 2, the audience builds through the week and peaks around the weekend evictions. Usually it rises over the run of the series, too, but this standard pattern was interrupted in the case of the most recent Celebrity Big Brother. The racist abuse, and the furore surrounding it, more or less rescued an ailing show. Its audience leapt, peaked with the eviction of Jade Goody on 19 January, and continued at a somewhat higher level for the final week of the show. The calculation of conflict that had inspired the casting produced the expected rewards in terms of audiences.

The crude figures, substantial though they are for Channel 4, conceal a very important distinguishing feature of the audience. Reality TV in general attracts audiences from across the social spectrum, and Big Brother’s numbers, at around 25 percent of the total audience, are less impressive than those of ‘observational’ shows such as Airport (67 percent), but it attracts a unique and valuable audience.27 The hardest audiences to get watching television are younger people. They have so many other things in their life, in contrast with those with families or living in retirement, that they spend much less time in front of the TV. On the other hand, they are a particularly attractive audience to advertisers because they have larger disposable incomes. Young men, in particular, have advertisers queuing up for their attention. As figure 3 demonstrates, Big Brother is very good at attracting a young audience. It is true that the audience is disproportionately female, but it still contains a large number of those attractive and elusive young male viewers. Big Brother also captures a relatively affluent audience.28 What is more, the people who watch the programme tend to be highly educated: 51 percent of students claimed to be regular watchers, for example.29

| Audience group | Percentages of total |

|---|---|

| 8-16 | 11.5 |

| 16-34 | 49.3 |

| 35-54 | 29.2 |

| 55+ | 10.0 |

| Male | 42.4 |

| Female | 57.7 |

This audience has few illusions about what it is watching. When asked to comment on the ‘reality’ of different television programmes, regular viewers rated Big Brother as much less likely to be giving an honest picture of the world than other ‘factual’ forms such as news and wildlife documentaries.30 Audience responses demonstrate a sophisticated approach to what they are seeing that has been honed over long periods:

The fact that audiences apply a sliding scale of factuality to reality programmes suggests one of the ways they have learned to live with this genre over the past decade. Audiences watch popular factual television with a critical eye, judging the degree of factuality in each reality format based on their experience of other types of factual programming. In this sense, viewers are evaluators of the reality genre, and of factual programming as a whole.31

When asked, viewers respond that they think that the situation has elements of reality in that it uses non-actors and has no script, but they are well aware that they are watching something that has been contrived by the producers to make entertaining television.32 Far from confusing the behaviour on the screen with the ways in which people ‘really’ behave, they are very conscious of the extent to which they are watching performances and this is in fact one of the main elements in what they think about the programmes. Like soap operas, which make their own, rather different, claims to be pictures of reality, one of the appeals of this kind of programme is that it provides topics for conversation and reflection in which people speculate about the dilemmas facing the characters, relate them to their own experiences and values, and use them to reach moral judgements about human behaviour.33 In this case, though, there is a specific element that is not present in the soap opera. Audiences put great stress on trying to discriminate between the ‘performance’ that the participants give and what they are ‘really like’:

Reality gameshows have capitalised on this tension between appearance and reality by ensuring that viewers have to judge for themselves which of the contestants are being genuine. In fact, audiences enjoy debating the appearance and reality of ordinary people in reality gameshows. The potential for gossip, opinion and conjecture is far greater when watching reality gameshows because this hybrid format openly asks viewers to decide not just who wins or loses, but who is true or false in the documentary/game environment.34

The tendency, at least in the earlier Big Brother shows, was for the winners to be drawn from the participants who were seen to be most genuine and most honest. The specifically unpleasant characters tended to be despised, marginalised, and voted out.

The evolution of the reality gameshow that we traced above in the case of Big Brother has produced a shift in the nature of the kinds of talk and judgement that audiences make. The triumph of nice people hardly made for the sort of compelling television that the producers were trying to provide and as the characters have become much more eccentric so the ways in which they are judged have changed. There is now a much clearer sense that the people who take part in what is sometimes called by audiences ‘humiliation TV’ are willing participants in their own exploitation and degradation. They are thought to be decreasingly ‘real’ and driven much more by an unbridled, and unbalanced, ambition. As one respondent, a 30 year old male gardener, told Hill:

When I saw a bit of Big Brother recently, I didn’t realise they were so, kind of, they are wannabes. I thought they were genuinely just people plucked out of nowhere. They all, like, wanted to be a presenter… Reality TV is, they’re more like sort of caged animals. And they’re agreeing to be degraded. Whereas in documentaries, I think, there is a tradition of respect and humanism in documentary making. There should be. People who want to make documentaries are different types of persons to people who’d get involved in reality TV.35

The participants in the ‘ordinary’ versions of Big Brother are today seen in much the same light as the minor celebrities of the celebrity version. They are treated as people who are ‘extraordinary’ in a negative sense and regarded as not deserving of the kinds of care, respect and fairness that television should extend to the really ordinary people who are seen in the news and in social documentaries. People still watch Big Brother, but today they are slightly ashamed of the pleasures they derive from it.

Critical responses

Reality TV in general, and Big Brother in particular, has generated an enormous amount of critical commentary. Much of this material is frankly moralistic, seeking to condemn everyone involved—producers, broadcasters, participants and audiences—as engaged in a debased form of discourse in the ‘bread and circuses’ mode of public distraction. Alongside this there is a small library of more substantial analysis from academics, some of which address important issues like surveillance. The installation of video cameras capturing every moment of life in the Big Brother house has obvious parallels with the spread of CCTV through the public spaces of the contemporary world.36 Another major issue of concern for academic analysis is the political implications of the fact that Big Brother commands a large, enthusiastic and largely young audience who pay to vote in considerable numbers. There are serious analyses claiming that shows like this can provide a model for the regeneration of bourgeois politics.37

From a Marxist perspective these issues, while interesting, miss the point about what kind of social relations are embodied in the show and what that helps us understand about the nature of contemporary capitalism. Producers and broadcasters are engaged in producing a marketable commodity, but to get the attention of the audience (and so sell it to the advertisers) they have to produce something that resonates with their intended audience and they have to recruit suitable participants. The central question then is, what kinds of motivations does the show offer to participants to take part and to audiences to tune in and to vote in such numbers?

In its origins, reality television contained a strong current that celebrated the labour of workers—at Angel tube station and the London Zoo, for example—and other examples of virulent class hatred directed at the rich (The Fishing Party). Even much more entertainment driven programmes such as Airport consisted in large measure of following working class people as they solved difficult and unusual problems. Work, in these programmes, is seen as a central part of human experience, and one that constantly challenges the capacity of workers, although there was seldom any explicit reference to the capacity of workers to challenge their conditions of labour. Programmes such as Big Brother represent a radical departure from that model in that they are designed to cut the participants off precisely from the exigencies of the world of work, and in that they represent a different account of life under capitalism. They inhabit the world of leisure, consumption and reproduction rather than that of labour, and one major attraction of the show is that it takes us into that world.38 It is the way in which it shifts of the boundary of what can be made public to include many things that are normally thought of as private that has provoked most of the outrage about the programme.

The explanation for the attraction of this move is to be found in the central features of human experience in developed capitalism. For most people, most of the time, work constitutes a realm of unfreedom. Not only can hours be long and wages low, but work involves following orders that are imposed from outside, and producing commodities over which one has no control. All of one’s creativity and individuality is subordinated to the commands of the employer and devoted not to the satisfaction of human needs but to the generation of surplus value. The analysis of this reality is an important part of Marx’s critique of capitalist production from the Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 through to the pages of Capital, and the basic ideas were generalised to society as a whole in the first part of a famous essay by George Lukács: ‘Reification and the Consciousness of the Proletariat’.39 The human being entering the workplace not only surrenders the fruits of their labour, but also their control over their labour itself.40 As contemporary capitalism has developed, and productive labour has come less and less to rely on ‘hands’ and more and more on ‘brains’, so the demands of alienated labour have become ever more onerous. The conformity demanded by the contemporary labour process includes much more than simply clocking in on time and doing what the foreman says—today you must abandon your individuality as well as your overcoat at the door.

There are two possible strategies in response to these realities. One is the confrontation with alienated labour, whose highest form is revolutionary struggle. As we all know, this is not an everyday activity for the mass of the population. The other is to try to discover some area of life which is not thoroughly permeated with the logic of alienation. In contemporary society that takes the form of a stress upon personal life and consumption. As Marx put it, ‘The worker therefore only feels himself outside his work, and in his work feels outside himself. He feels at home when he is not working, and when he is working he does not feel at home’.41 It is only here—in what we wear, the car we drive, the music we like, the relationships we form—that we can try to believe that we are truly and fully individuals pursuing ends determined by our own needs and desires.

There are, however, in capitalist society a tiny layer of people who for a variety of reasons are not anonymous and interchangeable. and whose personality counts for something. Some of them, such as footballers and film stars, are richly rewarded for their special attributes. Others have less tangible claims to distinction. But however they come to hold this status they are clearly visible in all their individuality, relationships and conspicuous consumption in the pages of Hello! and OK. The realm of celebrity is the realm of legitimised personality. One of the key characteristics of celebrities is that their private lives and doings are taken to be interesting and treated as public property. This is often denounced as an intolerable intrusion, but in fact it is the highest reward that can be bestowed under capitalism. Unlike the mass of the population, the celebrity is someone whose individuality is taken seriously. The idea of an individual magical escape into the world of celebrity is an attractive one if the alternative of collective action to achieve radical social change seems remote.

The evidence is that the people who participated in the first series of Big Brother did not anticipate how this could be a life-changing experience, but the potential was clear to those who tried to enter later.42 The would-be contestants knew that for some at least success in the house could lead to a different life, richer for sure but, just as important, a life as a celebrity.43 This is very clear in accounts of the selection process. By the time the British third series was recruiting, it was reported that a definite theme emerged in the tapes sent in for audition:

There was a great deal of nudity: people on the sofa nude, playing football nude, running down the street nude, one man naked except for an accordion in field full of cows, a naked girl smearing mud on her body, lots of women with tassels on their breasts doing stripping routines, a man jumping about on a pogo stick without his clothes.44

By taking their clothes off in front of a camera, potential participants were doing more than just signifying that they were ready to go along with what they imagined the producers might be planning. They were signifying their willingness to undertake the role of celebrity and make their most private attributes public. As the series has veered towards more eccentric participants, so contestants’ willingness to be public becomes clearer and clearer.45 Being on the show guarantees at least a short period of time when one can be a celebrity, and for some such as Jade Goody it actually provides the path to a longer stint in that role.

The intense desire to be recognised, to be a celebrity, to become a Big Brother contestant, is not primarily about the money that comes with success, although that is surely something that is in the front of people’s minds. Rather it is the desire to escape the drudgery of anonymous, alienated toil in which one counts for nothing. It is the desire to be recognised as somebody unique and distinctive by a wider circle than one’s immediate family and friends. The dream of celebrity is more than a magical escape from the constraints of relative poverty and the drudgery of routine labour. It is also, and most importantly, a magical attempt to transcend alienated labour, not by expropriating the expropriators but by evading the reality of being only the repository of labour power.

For the audience, too, the attraction of Big Brother is that it provides a site on which it is possible to discuss openly and without social discomfort the fascinations of the personal. The fact that what is normally private and guarded is displayed, indeed flaunted, in front of millions of us, not with the distancing conventions of drama but with the rhetoric of authenticity, provides a powerful stimulus to discussion and reflection about personal life in the modern age. It also provides an arena in which moral judgements about behaviour can be explored. The audience, as one of the production team put it, are ‘very moral. They reward good behaviour and punish bad behaviour’.46 One of the fascinations of the process is that it allows us to make celebrities out of people we believe have acted well and to punish those, like Jade Goody, who transgress what we believe should be the boundaries of proper behaviour. The people who win in Big Brother are the people the audience think deserve to become celebrities.

As we saw, these judgements depend on a balance between the ‘real person’ and their performance. The instability of the form, what is often called its ‘feral’ character, threatens this moral economy even as the producers are driven to extremes in order to sustain ratings. The shift towards more eccentric performers is not in itself a threat: after all an eccentric is merely a personality who does not fit into recognised social patterns and thus is very often a challenge to the smooth running of capitalism. However, the combination of eccentricity and humiliation detaches the performers from any universe with which the audience can identify, and this is a threat. It can still give pleasure to millions, but it is a different pleasure. As the audience recognises, it is shifting from an arena of moral exploration to a gladiatorial contest. Like the latter, it is a compelling spectacle, but it gives a guilty pleasure.

In conclusion

Reality TV in all its versions, but particularly in its reality gameshow format, represents, from the producers’ and broadcasters’ side, an attempt to respond to the changing economics of contemporary television. It is relatively cheap to make and it reliably garners an audience in the right numbers and with the right composition to sell to advertisers. Big Brother and some other similar game shows are firmly within this category, although they have additional elements that make them distinct both in their audience and in their appeal.

The fact that Big Brother gains such a large and enthusiastic audience of young people tells us something about life in modern capitalism. We cannot assume, as do so many populist commentators in media and cultural studies, that just because lots of working class people enjoy a particular artefact it is therefore in some sense progressive or oppositional. The reality is much more complex. A show such as Big Brother offers no challenge at all to capitalism, and indeed its structure reproduces some of the most pernicious effects of capitalism—human energy and initiative are ruthlessly exploited in order to make money. On the other hand, it does represent, in a weird and utterly unrealistic way, a dream of escaping from capitalism, of transcending alienated labour, escaping from conformity and flowering as an individual. Being a contestant makes you a celebrity for the duration, and you have a fighting chance of continuing in the role afterwards.

The fact that this dream of a better and fuller life is embodied in a game show rather than a political organisation is a sad but characteristic reflection of contemporary reality. When there is no obvious alternative that can provide a focus for mass discontent, all sorts of more or less magical solutions to the anger and frustration that mar millions of lives are seized almost in despair. The chances of winning on the National Lottery are tiny, but millions still buy tickets. The chances of becoming a Big Brother contestant are much bigger. Of those who become contestants, a celebrity career is a small possibility, but thousands are still prepared to try to make it.

Notes

1: Christians, for example can find their answers in Di Archer, Caroline Putnis and Tony Watkins, What does the Bible say about TV Game Shows? (Bletchley, 2001).

2: Peter Bazalgette, Billion Dollar Game: How Three Men Risked it all and Changed the Face of Television (London, 2005), p101.

3: Even the coming of Channel 4 did not alter this immediately. For the first decade from 1982 the ITV companies sold advertising on both their own channel and Channel 4, paying a levy on their total revenue to support the minority broadcaster. This changed only in the 1990 Broadcasting Act, which gave Channel 4 the duty of selling its own advertising from 1993 onwards, and thus introduced real economic competition into UK terrestrial television for the first time.

4: Colin Sparks, ‘Independent Production: Unions and Casualisastion’, in Stuart Hood (ed), Behind the Screens: The Structure of British Television in the Nineties (London, 1994), pp133-154. This model of production was pioneered by Channel 4, which produces virtually none of its own programmes.

5: A format is the key component of a show and, unlike an idea, can be copyrighted and thus sold.

6: Annette Hill, Reality TV (London, 2005), p6.

7: Survivor had originally been developed in the UK, but had first been shown to work in Sweden. It was that success that convinced CBS it was worth developing—Chris Jordan, ‘Marketing “Reality” to the World: Survivor, Post-Fordism, and Reality Television’, in David Escoffery (ed), How Real is Reality TV? Essays on Representation and Truth (Jefferson, NC, 2006), pp78-96.

8: Johnathan Bignell, Big Brother: Reality TV in the 21st Century (London, 2005), pp53-58.

9: Jean Ritchie, Big Brother: The Official Unseen Story (London, 2000), p9.

10: Hasan Suroor, ‘Shilpa Wins Big Brother Contest’, The Hindu, 30 January 2006.

11: Annette Hill, as above, p4.

12: Around 90 percent of applicants are described as white or European—Jean Ritchie, Big Brother 4: Up Close and Personal (London, 2003).

13: Peter Bazalgette, as above, p152.

14: Jean Ritchie, Inside Big Brother: Getting in and Staying in (London, 2002), p32; and Jean Ritchie, Big Brother 4, as above, p11.

15: Details online (accessed 16 February 2007) www.channel4.com/bigbrother/auditions/openauditions.html

16: There are guides as to how to succeed at this process, for example Jack Benza, So you Wannabe on Reality TV (New York, 2005), p68. He remarks, ‘There is nothing real about reality TV. Why? Producers… Producers will always manipulate people in a certain direction for the betterment of the show. They will lie, create non-existing stories, and stir up feelings among competitors all to create drama, which producers believe is better TV.’

17: Quoted in Jean Ritchie, Big Brother, as above, p26.

18: Toni Johnson-Woods, Big Brother (St Lucia, Queensland, 2002) pp130-131.

19: The programme makers ‘had to watch a drunken encounter between two house-mates, the controversial Jade and a trainee solicitor, PJ… In fact, in tabloidese, whether PJ had had a BJ was by no means clear, the couple having been under the bed covers. But when the covers fell away briefly, what was clear was PJ’s proud erection being vigorously manipulated by Jade. This much was edited out right away’—Peter Bazalgette, as above, p231. You can buy DVDs of the ‘bits they couldn’t show on TV’ for many of the series at the fan sites, for example: www.bigbrotheronline.co.uk/shop.htm

20: Annette Hill, as above, p32, provides the rating figures for series 1-4.

21: Jean Ritchie, Big Brother 4, as above, p11.

22: Phil Edgar-Jones, quoted in Paul Flynn, Big Brother: Access All Areas (London, 2005), p96.

23: Big Brother 7 gets ‘more twisted’.

24: Some commentators question these claims. Hill and Palmer write, ‘A sensitivity to the sort of coverage that excites the media became a determining factor in contestant selection. Producers soon learned that an exhibitionist streak was a useful factor in retaining viewers. Thus worldwide a series of strippers, dancers, and other flamboyant figures were installed in the houses with the hoped-for on-screen action. And so it proved with many European contestants doing away with the subtleties of flirting to engage in sexual congress at the soonest opportunity’—Annette Hill and Gareth Palmer, editorial in Television and New Media, volume 3, number 3 (2002), p252.

25: Peter Bazalgette, as above, p245.

26: Ian Bickerton, ‘Big Brother Row Could Help Endemol’, Financial Times, 23 January 2007.

27: Annette Hill, ‘Big Brother: The Real Audience’, in Television and New Media, volume 3, number 3 (2002), p327.

28: Janet Megan Jones, ‘Show your Real Face: a fan Study of the UK Big Brother Transmissions (2000, 2001, 2002). Investigating the Boundaries Between Notions of Consumers and Producers of Factual Television’, in New Media and Society, volume 5, number 3 (2002), p406.

29: Annette Hill, Big Brother, as above, p331.

30: Annette Hill, Reality TV, as above, p62.

31: As above, p173.

32: Writing of the audience in the US, Crew states, ‘Members of the sample group know that Survivor producers control what they see through the manipulation of activities, editing, and casting decisions. Viewers accepted the manipulation of the narrative as necessary to make Survivor an entertaining one‑hour programme’—Richard Crew, ‘Viewer Interpretations of Reality Television: How Real is Survivor for its Viewers?’, in David Escoffery (ed), as above, pp68-69.

33: Janet Megan Jones, as above, p408.

34: Annette Hill, Reality TV, as above, p70.

35: Annette Hill, Factual TV, forthcoming (2007), from chapter 7 of the manuscript.

36: One line of thought is that the Big Brother version of surveillance differs radically from the classical Benthamite model prison, in which the few guards observe the many prisoners, because the television version reverses those proportions and the audience of many watch the few participants. This, it is suggested, leads to a rudimentary form of subversion of, or even resistance to, the pervasiveness of surveillance in the outside world—John McGrath, Loving Big Brother (London, 2004), p206. A more orthodox line of reasoning is that a show like Big Brother ‘validates the pervasive surveillance of the rhythm of day to day life as a contemporary commonplace—a form of convenience and entertainment’—Mark Andrejevic, ‘The Kinder, Gentler Gaze of Big Brother’, in New Media and Society, volume 4, number 2 (2002), p267.

37: Stephen Coleman, How the Other Half Votes: Big Brother Viewers and the 2005 General Election, (London, 2006). It turns out that regular viewers are just as likely to vote in general elections as anyone else, but they believe that an electoral system modelled on the kind of detailed exposure participants in the house experience would give a better insight into political choices than do current forms of publicity. More extreme claims are made for the impact of audience participation in non‑democratic societies. The voting in the Chinese Supergirl contest (modelled on Thames TV’s Pop Idol) provoked a long debate about whether it constituted the first step towards Chinese democracy. See the articles collected at www.zonaeuropa.com/20050829_1.htm

38: This is the reason why Nick Couldry’s 2006 denunciation of Big Brother as embedding the success criteria of neoliberal labour is slightly mistaken. Reality TV, or the Secret Theatre of Neo–liberalism, available online.

39: For the more developed versions of Karl Marx’s account, see the Chapter on Capital in Grundrisse (London, 1973), and also chapter one, section 4 of Capital, volume one (Moscow, 1965). Lukács’s essay is in his History and Class Consciousness (London, 1971), pp83-222.

40: As the young Marx put it, ‘This relation [of labour to the act of production within the labour process] is the relation of the worker to his own activity as an alien activity not belonging to him; it is activity as suffering, strength as weakness, begetting as emasculating, the worker’s own physical and mental energy, his personal life…as an activity turned against him, independent of him and not belonging to him’—Karl Marx, Collected Works, volume 3 (Moscow, 1975), p275, available online.

41: As above, p274.

42: For the ‘innocence’ of those who volunteered for a first series, see the interviews with the participants in the first Finnish production cited in Ninna Aslama, ‘Twelve Truths About Big Brother Finland. Researching Participants’ Experiences of Reality Television’, unpublished paper.

43: Dean O’Loughlin, who was a runner up in the second series, wrote a thoughtful book in part reflecting on the experience of becoming a (minor) celebrity—Living in the Box: An Adventure in Reality TV (Birmingham, 2004).

44: Jean Ritchie, Inside Big Brother, as above, p29.

45: Perhaps the man with the pogo stick ought to try auditioning again.

46: Quoted in Paul Flynn, as above, p96.