When the first full lockdown began in Britain, on 26 March 2020, it would have been hard to imagine that over a year later restrictions on travel and socialisation would still be the norm, face masks would be required to visit shops and a myriad other precautions would be woven into the fabric of daily life.

Back then, I argued that Covid-19 presented governments with a dilemma. They were caught between complacency, as they sought to maintain the smooth functioning of the pre-pandemic economy, and top-down and authoritarian action to control the spread of the virus.1 Different states chose different routes through the crisis. Boris Johnson’s Britain represents something of an outlier—in its tardiness in introducing a lockdown and its premature reopening of workplaces and schools in summer and autumn 2020. It also failed miserably to construct a functioning test and trace system. As Colin Leys, co-chair of the Centre for Health and the Public Interest, argues:

There is…the embarrassment of £22 billion of sunk financial and ideological capital in the outsourced “NHS Test and Trace” programme… The result was a profitable failure: the companies involved, besides being grossly wasteful, never delivered on any of their targets and failed catastrophically to make ready for the huge second wave… But the project was also fundamentally misconceived, having no component for monitoring or enforcing the isolation of Covid-positive people and their contacts, and making no realistic provision for maintaining their incomes while not working… In August 2020, five months after NHS Test and Trace was set up, fewer than a fifth of people who tested positive and only 11 percent of their identified contacts were self-isolating.2

While this fiasco unfolded, by even the most conservative estimates, over 125,000 have died. Many more have faced short or long-term health consequences, to which must be added the impact of repeated, lengthy lockdowns. These have proved cataclysmic in terms of mental health, as well as sharpening economic inequality and reinforcing oppression—for instance, through trapping women in abusive relationships.3 Alongside older people and those with underlying health issues, black people, poor people and frontline workers have borne the brunt of the suffering. In London this is exemplified by the “Covid triangle”, the three boroughs of Barking & Dagenham, Newham and Redbridge. Here, racial discrimination and exploitation combined to generate “high levels of deprivation and job insecurity, vast income inequality, housing discrimination and medical disparities,” which, “when combined with the necessity to go to work, to take public transport and to share space in densely packed housing…provided the perfect breeding ground for a deadly virus”.4

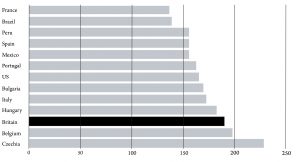

Deaths per capita in Britain are among the worst in the world (figure 1). Had the government persisted with its herd immunity approach, rather than being spooked into the first lockdown, the death toll could have been far higher. A gruesome test case is presented by Manaus, Brazil, where dense housing and poverty, and the collapse of health services, allowed the disease to rage through the city last year. A study in October 2020 estimated that 76 percent of the population had been infected, above the theoretical threshold for herd immunity (thought to be somewhere around 60 percent).5 Yet, in spite of this, it seems that “transmission in Manaus…continued, even in the presence of non-pharmaceutical interventions”.6 More alarmingly, by January this year, hospitals were again overwhelmed in the city, with death rates exceeding those in the first wave. Overall excess deaths for the city have been estimated at a staggering 435 per 100,000 people.7 Waning protection may have been one factor.8 Probably more important is the emergence of new strains—in particular “P.1”, which appears to have become dominant in Manaus and seems to evade immunity from previous strains as well as being more transmissible.9

Figure 1: Death per 100,000 population (countries with over 10,000 deaths)

Source: John Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Centre, 20 March 2021

Although vaccination programmes remain important in reducing the spread of the disease, the initial failure to contain the virus, and its eventual mutation, mean that successful eradication of Covid-19 is now unlikely. “Zero Covid” has rhetorical appeal as a slogan, but the reality is that the virus will resurface, even in countries with widespread vaccination. The sole human disease ever known to have been eradicated is smallpox. Unlike Covid-19, smallpox can only be caught and transmitted by humans, with no animal reservoir, and has a very short period between infection and symptoms appearing, making it a good candidate for eradication.10

The new Covid-19 variants that have emerged in recent months show how difficult even local elimination of the virus is likely to be. Three “501Y lineages” have now become prevalent in different areas, developing independently in Britain, South Africa and Brazil. In the first case, the variant seems more transmissible, in the second it is feared that it may evade immunity and, in the third case, possibly both.11 In a survey of over 100 scientists by Nature, most saw the virus becoming endemic. This may mean it becomes a relatively mild respiratory disease, predominately infecting children, like other coronaviruses, with the possibility of “immune escape” through mutation.12 However, even under this relatively benign scenario, there is the possibility of variants established in animal reservoirs crossing back into human populations. More generally, the pandemic reveals that the incursions of capital into ecosystems, and the accompanying commodification of nature, have reached a point at which zoonotic transfer (from animals to humans) of viruses is a pressing danger. Coronaviruses, which exist in bat populations among other reservoirs, along with other viruses such as influenza, which are prevalent in wildfowl, will be more likely to erupt into human populations. This is a danger of which writers such as Mike Davis and Rob Wallace have been warning for years.13

The needle and the damage done

In Britain, the vaccination programme has been seen as one of the few successes amid the dismal failure and cronyism of the government’s Covid-19 response. It is no coincidence that Johnson’s approval rating has risen with the rollout of the vaccine. In October 2020, 25 percent more people thought Johnson was doing “badly” than doing “well”; by March 2021 this had shrunk to just 3 percent.14

Behind the jingoism that has accompanied the programme, it is important to understand that its success rests on two factors: a huge gamble authorised by Johnson, which paid off beyond his wildest dreams, and the resilience of the NHS, in spite of the contempt shown for it and its employees by this and previous governments. First the gamble—faced with the fiasco of its response to the outbreak of Covid-19, the government put in early orders for 400 million doses of untested vaccines at a cost of about £11.7 billion. This included 40 million doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine and 100 million of the Oxford-AstraZeneca version, which both proved unexpectedly effective and gained early approval for use. British negotiators, unlike their European Union counterparts, inserted clauses in their contract with AstraZeneca, not simply ensuring that doses manufactured in Britain would be used here first, but also forcing the firm to cover shortfalls from elsewhere in its supply network. However, it should be stressed that the success also rests to a large extent to the existence, however battered by privatisation and austerity, of an NHS that is both relatively centralised and includes a primary care system built around GP’s surgeries. These elements combined to increase the effectiveness of the rollout.15

There may yet be problems for the British vaccine programme. On top of the growing danger from new variants, there were reports by mid-March of constraints in the vaccine supply, primarily because of delays in delivering AstraZeneca doses produced in India.16 In general, “vaccine hesitancy” is less of a factor undermining the programme in Britain than in most European countries.17 However, the hesitancy that does exist in countries such as Britain, as in the US, is heavily concentrated among black people. This reflects an entirely understandable mistrust of the government and medical establishment, which could only be fully addressed through the genuine collective participation of communities in shaping the vaccine programme. In a moving account of her own decision to get vaccinated, a black physician in the US argues:

The racial disparity in Covid-19 mortality has nothing to do with race and everything to do with structural racism… This lack of trust is not just the result of residual pain from past atrocities like the Tuskegee experiments… Many patients of colour, including myself, can describe present-day experiences in the health care system where we have been discounted, ignored and devalued.18

In spite of these problems, Britain’s vaccine programme so far looks a dazzling success compared to the picture elsewhere in Europe. In the face of growing vaccine nationalism, the EU has proven itself utterly dysfunctional. The vaccine rollout was delegated to the European Commission president, Ursula von der Leyen, who, during her time as German defence minister, had “messed up every major procurement project she laid her hands on,” according to Wolfgang Streeck. He adds that the Commission’s staff, tiny and inexperienced in procurement on this scale compared to the civil services available to major governments, were incapable of dealing with the “corporate sales sharks” of big pharma. Moreover:

The EU delegation had to check back with 27 nervous national governments facing 27 scared national electorates… Price was a major concern for the Commission, in contrast to the UK and US governments who were paying with their own money rather than that of others… Even more importantly perhaps, the EU delegation had no authority to promise subsidies for new production facilities.

Adding to the chaos was pressure from Emmanuel Macron to buy vaccines from French pharmaceutical giant Sanofi, which announced in January that its product would not be available until the end of 2021.19

As rows over vaccine supply broke out between EU leaders and the British government, use of the AstraZeneca vaccine was suspended in many European states amid claims, still unproven, of serious side-effects and threats by von der Leyen to stop shipments of vaccines to countries showing insufficient “reciprocity”. Such moves would not simply reinforce the pattern of vaccine nationalism but would also disrupt the complex global production networks through which vaccines are produced.20 While these debates continue, much of Europe is now gripped by a “third wave” of the virus, fuelled in part by new variants. This is forcing states to introduce new restrictions and choking off the fragile economic recovery. Of course, the situation in many countries in the Global South is worse still, with many unable to make their own purchases and reliant on the Covid-19 Vaccines Global Access (Covax) scheme, which plans to vaccinate around a quarter of the population of the 92 poorest countries.21 The availability of vaccines will ultimately reflect a world structured according to the power of capital, not one designed to meet human needs.

Economic shocks

Meanwhile, the pandemic has precipitated the sharpest economic contraction experienced by contemporary capitalism. The disruption to patterns of both supply and demand induced by the outbreak have hit particularly hard in Britain, making it the worst affected major economy so far.

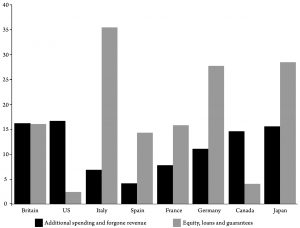

This is not a momentary setback. Long-term growth, sluggish since the 2008-9 crisis, is likely to deteriorate further, even if the public health crisis abates, with the global economy entering a new phase of its “long depression”.22 The dominant trend across the advanced capitalist states in recent decades, contrary to the rhetoric of neoliberalism, has been to radicalise the pattern of state and central bank interventions that are increasingly been required to support growth.23 As figure 2 shows, even before Joe Biden’s $1.9 trillion stimulus (a further 10 percent of GDP) was agreed, several major states had enacted economic stimulus policies at a level unseen outside of wartime.

Figure 2: Discretionary fiscal response as percentage of GDP by end of 2020 in selected countries

Source: IMF database of fiscal policy responses to Covid-19.

Britain is no exception. An estimate in autumn 2020 by the Institute for Government suggested that the government absorbed about two-thirds of the expected hit to private sector income, either through transfers such as the furlough scheme or by accepting a loss of tax revenue. This has significantly increased public sector debt.24 Chancellor Rishi Sunak’s March budget, then, reflected the contradictory imperatives faced by the Conservative government. On the one hand, it extended the furlough scheme through to autumn 2021, deferring a sharp rise in unemployment, and it offered tax incentives to encourage firms to invest. On the other hand, it reminded us that there are limits to the government’s largesse—proposing future rises in corporation tax, which, if they happen, will reverse the direction of policy over recent decades, and squeezing future public sector spending.25 The nasty side to the government’s spending plans was reinforced by its proposal for an increase of just 1 percent for NHS workers’ pay for 2021-2, likely to be a real terms pay cut, along with a complete freeze across the rest of the public sector. For all that the government has spent big during the pandemic, the indications are that Sunak and Johnson will eventually seek to reduce the scale of public debt. This can happen through some combination of austerity and tax rises—or it could come about as a side effect of a sustained economic boom boosting revenues. What are the prospects of the latter?

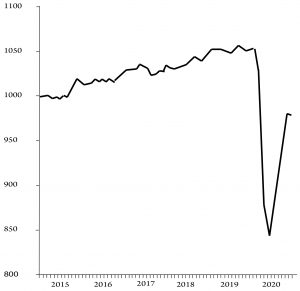

If the virus can be contained in the short term—and, as suggested above, this is a big “if”—there will be some rebound in economic activity. This is particularly the case in the US in the wake of Biden’s stimulus deal, but to some extent this will take place in Britain too, as “pent-up” demand from those who have retained their jobs and possess larger disposable incomes is released. However, this rebound is unlikely to take the form of a sustained boom. Once the “sugar rush” of pent-up demand is spent, it is unlikely the economy will shift onto a new and more dynamic track—the economic “fundamentals”, in particular the rate of profit across advanced capitalist states, remain too weak.26 In the case of Britain, with the exception of a brief upsurge in the wake of the recession of the early 1990s, profitability has stagnated since the 1970s, if anything trending downward (see figure 3).

Figure 3: UK internal rate of return on capital stock (percentage)

Source: Penn World Tables 10.0. See Roberts, 2020, on the use of measure as a proxy for the rate of profit.

As authors in this journal have argued, capitalist dynamism is driven above all else by profitability. The long post-war decline and the subsequent stagnation of profit rates makes economies increasingly dependent on credit expansion and financial exuberance, along with state and central bank support, to sustain growth. However, this very support also leads to the creation of a mass of unprofitable capital, including so-called zombie firms kept alive through cheap credit, something that has been reinforced by the pandemic.27 The astonishing levels of debt—corporate non-financial debt now surpasses global GDP—will weigh down any recovery.28 This poses a dilemma for those presiding over the system: sustain largely unprofitable businesses, along with the profitable ones, or risk a much wider shakeout in the hope that, eventually, rapid growth develops. The tendency over recent decades has been to pursue the former path, even at the cost of relative stagnation.29 However, as one strategist for Morgan Stanley put it in a recent Financial Times column:

There is increasing evidence…that four straight decades of growing government intervention in the economy have led to slowing productivity growth… Increasingly, the money printed by central banks goes to finance government debts…and much of it has stoked…asset price inflation… Easy government money has ended up supporting the least productive companies, including heavily indebted “zombies” that would otherwise fail.30

State support for the economy is not only keeping failing firms alive; it is also disguising the development of high levels of effective unemployment and underemployment. This becomes apparent when one looks at the collapse, and only partial recovery, in hours worked during the pandemic (figure 4). A staggering 11.2 million jobs, about a third of the entire labour force, had at some point been furloughed by the beginning of February—with about 4.7 million still on furlough at that date.31 It remains to be seen how many of these workers will have jobs to return to when the scheme is eventually withdrawn, particularly in areas such as retail.32 Marxist economist Michael Roberts is right to warn of long-term “scarring” to employment and investment capacity, even if the direct impact of the virus begins to recede.33

Figure 4: Index of hours worked in Britain in millions per week

Source: Calculated from Office for National Statistics data.

Authoritarian strains

In other words, alongside the pandemic, and the broader, ongoing ecological crisis within which it is situated, the economic situation remains dire.34 What does this multidimensional crisis mean for politics under the pandemic? One tendency will be the continued polarisation of global politics as the neoliberal centre that once dominated politics erodes. The emergence in this context of a range of radical right and fascist formations—strikingly demonstrated in January by the attack on the Capitol in Washington by Donald Trump supporters—is charted by Alex Callinicos’s magisterial article in this issue.

Here in Britain there are efforts by the far right to reorganise themselves through participation in anti-lockdown protests. However, there are also elements of the Conservative Party adapting to hard right politics—and, like Trump in the US, lashing out at the left and movements such as Extinction Rebellion and Black Lives Matter. The authoritarian element here is part of a broader trend: Greece has seen protests in defiance of its lockdowns after police beat up a man in Athens, demonstrators have clashed with riot police in the Spanish state over the jailing of rapper Pablo Hasél for insulting the monarchy, while repression deepens in France, as discussed in Claude Serfati’s article in this issue.35 In the case of Britain, the most obvious sign is the move by home secretary Priti Patel to use the conditions of lockdown to drive through the draconian Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill. As well as creating new stop and search laws and criminalising trespass, the bill would further restrict the right to protest—criminalising those deemed to be “causing public nuisance”, allowing police to impose a start and finish time on protests, and threatening those who topple statues with up to ten years in prison.36

Yet there is resistance to the Police Bill. The killing in South London of Sarah Everard, a 33 year old woman, with a police officer accused of the murder, led to an outpouring of rage against sexism. When a vigil for Everard held on Clapham Common was physically attacked by police, this anger began to fuse with opposition to the bill. The outcry forced even Labour leader Keir Starmer to shift to opposing the government’s plans. Of course, Starmer’s resistance to the strengthening of police powers is not to be relied upon. When, in the context of a mass “Kill the Bill” protest in Bristol, a police station was attacked and a police van burned, the Labour leader rushed to condemn the action as “inexcusable”.37

Even the limited outbreak of actual opposition from Labour’s frontbench is a rarity. In the run-up to Sunak’s budget, Starmer and his shadow chancellor, Anneliese Dodds, burnished their pro-business credentials by making clear their opposition to any immediate rise in corporation tax. In general, union leaders have echoed Starmer’s approach. Leadership from the National Education Union gave encouragement to educators to refuse to return to schools in early January, forcing the government into a U-turn and giving a glimpse of the collective strength of workers. Nevertheless, this has been the exception not the rule. In the absence of any meaningful resistance from this quarter, the revolutionary left must do what it can to offer a way forward. That means taking heart from—and continuing to build—movements such as those protesting sexism in the wake of the murder of Everard, the worldwide day of action against racism held on 20 March, or the actions planned against the Police Bill.38

It also means learning the right lessons from the defeat of Jeremy Corbyn’s project. The retreat Starmer is leading to the political centre ground is one example of learning the wrong lessons, but another is to simply look to a rehashed version of Corbynism. Momentum co-founder James Schneider has recently offered yet another version of the “in and against the state” approach for Novara Media. For Schneider this means “winning elections within the current system and balance of forces”, in the hope that the action of a left government can somehow spur a radical movement to life. In practice today it means a reversion to “municipal socialism”, with activists urged to gain “practical experience in using the state for progressive ends through local government”.39 There are few things more likely to sap the vitality from whatever movements do exist. Instead, the goal must be both to build movements outside the framework of the capitalist state and to expand the circle of those within these movements committed to a thoroughgoing revolutionary transformation of society. Such a process, mobilising the collective power of workers, ultimately requires a confrontation between the revolutionary forces and the capitalist state.

This is a lesson not just of Corbynism but, far more dramatically, of the Arab Spring, which erupted one decade ago, key participants of which are interviewed by Anne Alexander in this issue of International Socialism. The interviews show once more the immense creative energies that are unleashed by revolutionary processes but also the necessity for mass revolutionary organisation at the heart of such processes if they are to achieve a decisive break with capitalism.

Joseph Choonara is the editor of International Socialism. He is the author of A Reader’s Guide to Marx’s Capital (Bookmarks, 2017) and Unravelling Capitalism: A Guide to Marxist Political Economy (2nd edition: Bookmarks, 2017).

Notes

1 Choonara, 2020. Thanks to Richard Donnelly and Mark Thomas for feedback on an earlier draft.

2 Leys, 2021.

3 Roesch and others, 2020.

4 Raval, 2021.

5 Buss and others, 2021.

6 Sridhar and Gurdasani, 2021. For a brief account of some of the complications involved in assessing the potential for herd immunity, see Miyasaka, 2021.

7 See the data compiled by Bruce Nelson—https://t.co/6g4HHEAuNY

8 There is evidence from a Danish study that those with natural immunity under 65 years have about 80 percent protection from reinfection, those over 65 closer to 50 percent. However, the study looks at those initially infected in March-May 2020, considering whether they were infected again in September-December, and cannot offer much certainty about immunity over longer periods of time—Hansen and others, 2021.

9 Taylor, 2021. Along with these factors, there is a possibility that the original estimate of infection levels, drawn from a study of blood donors, was an overestimate; however, a careful analysis published by The Lancet suggests this is unlikely to offer a full explanation (and there is evidence that studies of this kind may underestimate infection levels)—see Sabino and others, 2021.

10 Attempts to eradicate other suitable candidates, such as polio and guinea worm, continue, thus far unsuccessfully. On the principles of disease eradication, see Dowdle, 1998.

11 Viruses mutate over time, but precisely why these three variants emerged when they did is still the source of speculation. According to one paper (a non-peer-reviewed pre-print), it may reflect changes in the landscape confronting the virus, perhaps due to relaxation of lockdown measures or due to the prevalence of potential hosts with antibodies. It may also have been a consequence of the interaction of mutations within the minority of chronically infected people over long periods, which took time to develop—Martin and others, 2021.

12 Phillips, 2021.

13 See Choonara, 2020, and the references therein.

15 Baraniuk, 2021; Schiffling and Breen, 2021. It should be added that, in violation of all the neoliberal nostrums, the development of the vaccines themselves was bankrolled by states—a good example of what Mariana Mazzucato calls “the entrepreneurial state”. See Mazzucato, 2018.

16 Torjesen, 2021.

17 Imperial College London, 2021.

18 Nephew, 2021. The Tuskegee experiment, which began in 1932, recruited 600 black people, some with latent syphilis, allowing the disease to progress without proper treatment as they died or suffered horrendous health impacts. The study ended only in 1972.

19 Streeck, 2021.

20 Financial Times, 2021.

21 Pilling, Findlay and Harris, 2021.

22 Roberts, 2021a.

23 Choonara, 2018.

24 Lilly and others, 2020, p11.

25 Institute for Fiscal Studies, 2021.

26 Roberts, 2021b.

27 Gagnon, 2020.

28 Wigglesworth, 2020.

29 See Choonara, 2018, for a more detailed discussion.

30 Sharma, 2021.

31 HM Revenue and Customs, 2021.

32 See Thomas, 2021.

33 Roberts, 2021c.

34 See Ian Rappel’s article in this issue of International Socialism for a vivid study of another aspect of this ecological crisis.

35 Clark, 2021.

36 Casciani, 2021.

37 Grafton-Green, 2021.

38 See Kimber, 2021.

39 Schneider, 2021. See Nick Clark’s article in this issue for a survey of responses to the failure of Corbynism.

References