Hartlepool is the sort of place that London-based newspapers send their journalists to go on safari. They marvel at the house prices, joke about the local food and tend to discover swathes of backward opinions among the benighted residents. However, even putting aside this predictable media circus, the Hartlepool parliamentary by-election on 6 May was undoubtedly a sign of serious developments. Paul Williams, the Labour candidate, received just 28.7 percent of the vote, with 51.9 percent going to Jill Mortimer, the Conservative. It was Labour’s lowest vote share in the constituency and its predecessors in 78 years. It was the first time the Tories have won in Hartlepool for 62 years. A few weeks later, at the Batley and Spen by-election, Labour barely clung on, beating the Tory by just 323 votes.

Normally the party of government does badly in by-elections. They are a chance for people to show all their bubbling frustrations with the people in charge. This is why the governing party has lost in 34 of 67 by-elections since 1979. An incumbent party has managed to win a seat from another party at a by-election in just three cases in the past 40 years.

It is all the more shocking because the Tories had, at the time, presided over nearly 130,000 deaths from Covid-19, one of the worst deaths per capita rates in the world. The subsequent revelations from Dominic Cummings, Boris Johnson’s former chief adviser, have underlined the murderous decisions that coldly ensured mass deaths. As Cummings told a joint hearing of parliament’s health and science committees: “Tens of thousands of people died who didn’t need to die”.1 Corruption is inbuilt in bourgeois politics, particularly due to its links to big business interests. Nevertheless, there has rarely been a government that is so openly corrupt as in Britain in 2021. It oozes contempt for accountability, handouts for its friends and favours for the rich. Johnson is personally at the centre of all of this.

In 1755, William Hogarth produced The Humours of an Election, a series of oil paintings depicting the bribery, mayhem, wastefulness and venality of politics. We could do with another equally skilled artist today to show the handing out of contracts for personal protective equipment, the calculation of the piles of bodies and much else. In addition, the government is recommending a pay rise of just 1 percent for health workers—effectively a pay cut—and implementing a pay freeze for millions more public sector workers. Simultaneously, it is squeezing funds for council services. Yet the Tories are still winning elections.

There were important factors in the Tories’ favour. They basked in a reflected rosy hue from the success of the vaccine rollout and the hope that the worst of the pandemic might be over. Through the efforts of the NHS and the government’s gambles on vaccine procurement, Britain has seen a much swifter vaccine distribution than most other countries. The Tories are acting like an arsonist who has torched a row of houses and now says: “Look how well the firefighters are doing! Give me some credit!” Still, there is no doubt their rhetoric is having an effect.

The vaccine successes have also triggered a more favourable view of Brexit. At the start of this year, the implementation of new rules and regulations flowing from the Tories’ version of Brexit led to vast lorry queues around ports, headlines about possible shortages of basic goods and fury from those who now had to wade through extra bureaucratic form-filling. However, as European Union countries descended into squabbling and competition over a relatively small pool of vaccine, Britain’s independent stance suddenly looked a much better bet. By 13 April 2021, YouGov pollster Peter Kellner could claim that Brexit was “more popular than it has been at any point since the referendum” due to the vaccine issue. This reinforced Bloomberg’s research, which found that two-thirds believed that being outside the EU has helped Britain’s vaccination programme. Kellner explained: “What the pollsters agree on is that in the last three months, after five years of stability, when very few Remain or Leave voters were changing their minds, there has now been a shift. The row over vaccines and performance of the vaccines has been responsible for the shift”.2

The Tories have skilfully used the issue of Brexit to divide working-class people. Johnson falsely posed as the friend of ordinary people who had been belittled and ignored after the 2016 vote to leave the EU. Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson, an alumnus of Eton and Oxford, outrageously paraded his supposed opposition to the elitism and privilege that, he said, was silencing the voices of Leave voters. Nonetheless, he could do this only because there were many forces that were indeed trying to reverse the vote. These included not only the Liberal Democrats and big business but also the Labour Party. Under pressure from Keir Starmer as well as some on its left, Labour embraced the demand for a second referendum. Far from being some passing episode that has been forgotten now that Britain has left the EU, Brexit has become a symbol for all the ways that ordinary people are despised and lied to. Having Starmer, the man who wanted to reverse Brexit, as Labour leader constantly reminds some workers of the insult this represented.

Outside of England, incumbent parties that were seen to have taken a slightly more credible route through the pandemic did well. The Scottish National Party gained, as did Welsh Labour. However, Starmer had failed to offer any serious alternative to Johnson. Morever, at the time of the elections, the anticipated avalanche of job losses had been postponed for most people by the continuation of the furlough scheme, which gives employers up to 80 percent of their workers’ wages in order to stop them being sacked. For now, the Tories are blending government economic intervention with deliberate divisiveness and increased oppression. The Queen’s speech on 11 May saw promises (most of which will turn out to be empty) to help ordinary people—more infrastructure, investment in adult skills, more cash for further education. Yet this came together with a right-wing pitch: special protections for military veterans, nastier attacks on refugees, restrictions on protest and longer prison sentences. The government is also moving forward with its “free speech” agenda—by which is meant the suppression of opposition to right-wing speakers on university campuses and attacks on pro-Palestinian activists through spurious allegations of antisemitism.

None of this, however, shrinks the scale of Labour’s crisis. It was not just Hartlepool that saw heavy losses. The English council elections were also a disaster. The Tories saw a net gain of 11 additional councils, winning 234 more councillors. Labour lost control of ten councils and has 326 fewer councillors.3

Around half of the seats being contested were in places where last year’s local elections were postponed and thus were last contested in 2016. At that time, the Conservatives and Labour were neck and neck in the polls, so the results acted as a test of whether the polls that have now consistently shown the Tories ahead are true. The verdict was unequivocal. The BBC collected detailed local voting figures across 1,200 wards and found the Tory vote was up on average by eight points in those last fought in 2016. Labour’s support in these wards fell by three points. The other half of the seats were in councils that were always due to have elections this year and were last contested just before the 2017 election, when the Conservatives were well ahead. So again, this is a test of whether the Tories, despite all their failures, are actually still holding support. In these seats, the Conservative vote was down by just one point, and Labour’s vote edged up by no more than one point. That reveals a big continuing Tory lead.

According to the BBC’s projection of the local election results into the equivalent of a Britain-wide share of the vote, the Conservatives’ performance was the equivalent of winning 36 percent of the vote in a general election. That makes it the party’s second best local election results since it first regained office at Westminster in 2010. The same measure showed Labour on 29 percent, seven points behind the Tories. That is better than the 12 point deficit at the 2019 general election, but still an extraordinary gap against such useless opponents.4 Facing the truth requires understanding that the Tories have the support of just over a third of voters, but that Labour had backing from only just over a quarter.

However, this is not certain to continue. There are moments when parties are so incompetent and so obviously corrupt that even a weak opposition can win. At the 1997 general election, there was widespread rejection of the results of the neoliberal assaults from Tory governments headed by Margaret Thatcher and then John Major. This mood was so strong that almost any Labour leader would have won and the “social liberalism” peddled by Tony Blair could triumph. Moreover, we must remember that politics is now much more febrile than previously and loyalties far thinner. Now the Tories are celebrating, but just two years ago they received just 8.8 percent of the vote in the European Parliament elections held across Britain. UKIP and the Brexit Party soared to huge electoral successes and are now thankfully extinguished. Similarly, Labour won 40 percent of the vote in 2017’s general election, but only 32 percent two years later.

In the immediate term, class issues are destined to batter into public consciousness. The furlough scheme is set to end on 21 September. Unemployment and poverty are set to increase, with the ruling class seeking to make workers pay the costs of the pandemic. In Scotland—as covered in depth elsewhere in this issue of International Socialism—there is growing tension between Johnson’s determination to hold the British state together and the demand for a second independence referendum that animated the SNP’s election victory. This democratic struggle, which is linked to a desire for real social change, could have ramifications across the whole of Britain.

Was it Corbyn?

The Labour right had an instant explanation for the party’s troubles—blame the left and, in particular, Jeremy Corbyn. This is astonishing given Starmer has spent his entire time as leader driving the party rightwards, seeking to marginalise the left and driving out pro-Palestinian activists. Simultaneously, he has steered away from open confrontation with the Tories and instead adopted the role of a “constructive opposition”—embracing the military, the British flag and the police while spurning the Black Lives Matter movement.

Nevertheless, this stampede to the right, motivated by the drive to become acceptable to the ruling class, was still too little and too late according to some in Labour. Arch-Blairite Peter Mandelson pinned the blame for electoral failure on “long Corbyn”, the continuing malign after-effects of having had a left-wing leader. Writing in the Daily Mirror, Mandelson claimed:

Jeremy Corbyn still casts a long shadow. A woman voter in Chaucer Avenue told me, “I cannot believe I am telling you this, but I voted Tory because of Corbyn.” When I told her Keir Starmer is very different, she snapped back, “You will have to prove it—you can earn my vote before I come back.” Locally too, people were disillusioned with Labour councillors who were aloof from them, speaking a language that owed more to far-left platitudes than their everyday lives.5

So the Labour right’s demonisation of Corbyn and its councillors’ meek passing on Tory cuts was not the problem, but rather the “far left”. Mandelson was backed up by Blair, who called for much deeper restructuring of the Labour Party so that it could be properly rebuilt: “The Labour Party won’t revive simply by a change of leader. It needs total deconstruction and reconstruction.” According to Blair, Labour’s crisis is rooted in the fact that:

Today’s progressive politics has an old-fashioned economic message of big state and tax and spend, which, other than the spending part (which the right can do anyway), is not particularly attractive. This is combined with a new-fashioned social and cultural message around extreme identity and anti-police politics, which, for large swathes of people, is voter-repellent. “Defund the police” may be the left’s most damaging political slogan since “the dictatorship of the proletariat”.6

None of this explains why people voted for Corbyn in such huge numbers in 2017 and why they are so turned off by Starmer. Since the May elections, opinion polls have put Labour as much as 18 percent behind the Tories overall. The Tories enjoy a 36-point lead among the C2, D and E social grades that make up a substantial part of the working class. Another poll saw Starmer’s net favourability rating drop 11 points in a month to minus 18, his lowest ever rating. Only 24 percent of people said he would make the best prime minister, compared to 48 percent for Johnson.

None of this should be cause for anyone on the left to snigger or celebrate. It is outrageous that Labour’s failings have enabled the murderous and corrupt Johnson to persuade nearly half the British population that he is the best choice. One of the most telling statistics was that 41 percent of people thought Johnson “represents change”; Starmer was on only 31 percent.

Starmer’s own response to defeat was to proclaim a ruthless war on the left and then engage in a confused retreat. He said he accepted “full responsibility”, only to sack his deputy Angela Rayner as party chair and national campaign coordinator. This scapegoating led to outrage, and Starmer then had to offer Rayner a clutch of jobs that may actually increase her profile. This was not so much a night of the long knives as a night of the blunt knight for Sir Keir Starmer, who has managed to unify both the left and the right in opposition to him.

The northern reactionaries

Of course, Starmer bears significant responsibility for the failures of 6 May, but the rot goes much deeper. Unfortunately, a popular explanation for Labour’s decline is that today there is something inherently reactionary about working-class people in general and, in particular, those who live in the north of England.

After the May elections, author and journalist Paul Mason wrote:

Socially conservative working-class voters despise the poor, just as they despise “students”, “wokeness”, refugees and human rights. Their politics are now dictated primarily by their identity, not their economic interest.7

Nobody would doubt that there is a section of workers (and middle-class people) who have swallowed whole all the foulness pumped out from the top of society. It could hardly be otherwise given the scale of the racist ideas and practices that have been peddled by the Tories and left unchallenged by far too many Labour politicians and trade union leaders. The Tories have deliberately sought to create divides based on British nationalism, racism and law and order in order to shore up their electoral support.

An example is the so-called Sewell report, published by the Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities in March 2021, which decreed that institutional racism does not exist and is a fiction peddled by malicious campaigners and academics. The Tories knew this would create a storm of criticism, but they did not care. Instead, they are grabbing the chance to cohere around themselves a section of the population who have been persuaded that calls for anti-racism have gone too far and are threatening the British “way of life”. Such manoeuvres will increase racism, and, in the absence of serious pushback from anti-racists, they can pay electoral dividends for the Tories.

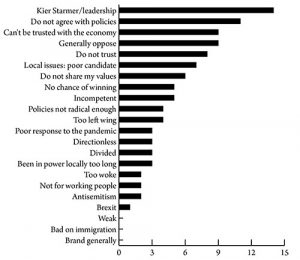

Nevertheless, it is important to challenge the idea that most people were pulled by such factors on 6 May. A poll for Channel 4 by J L Partners asked people across England the main reason why they did not vote Labour in the elections (see figure 1). Only 4 percent said Labour was too left-wing, and 2 percent that it was “too woke”. “Bad on immigration” came even lower—at zero percent. The most popular reason given, at 14 percent, was “Keir Starmer/leadership”, and another 11 percent said they either did not agree with Labour’s policies or that these policies were unclear. Typical comments about Labour from those who went over to the Tories were “poor leadership and haven’t been very vocal for a year” and “don’t think Keir Starmer is proving to be a good leader and never seems to offer any alternative policies to Boris Johnson”.8

Figure 1: Main reasons people did not vote for Labour in May 2021 local elections (percentage)

Source: YouGov, 2021.

These finding were confirmed by a major YouGov survey, taken the weekend before the elections, of people living in the “Red Wall”—the traditionally Labour seats that have now fallen to the Tories and gone “blue”. The poll covered 51 constituencies across the North and Midlands of England that the Conservatives won from Labour at the 2019 general election. In the local election voting that followed, Labour slightly outperformed the Tories by 40 percent to 37 percent. The results showed that Red Wall residents believe that Britain made the correct decision in voting to leave the EU. Some 50 percent agree that Britain was “right to leave”, compared to 37 percent who believe it was the “wrong” decision. Red Wall occupants are more favourable toward Johnson (net favourability of plus 1) than they are to Starmer (minus 18), and prefer the Conservative party (minus 4) to Labour (minus 18).

Importantly though, these results fail to show any great wave of support for Johnson or the Tories. Overall, they do not like them—but they are even less impressed by Starmer’s Labour. People in the Red Wall are nonetheless more likely to think that the Labour Party respects “people who live in your area” than the Conservatives. Four in ten (41 percent) say that Labour either somewhat or completely respect people in their area, while 33 percent say that it tends not to. Crucially, as Patrick Walker, research manager of YouGov, comments:

The Red Wall is no more socially conservative than Britain as a whole, and the characterisation of voters in these areas as predominantly “small c” conservatives concerned about social liberalisation or culture wars is not supported by polling evidence… People in Red Wall areas are very much supportive of things like multiculturalism, with 50 percent agreeing that “having a wide variety of different ethnic backgrounds and cultures is part of British culture.” Just 31 percent suggested that this undermined British culture. Some 40 percent agree that immigration has “generally been good for the country”, although 33 percent believe that it has on the whole been a bad thing.9

On transgender rights, 35 percent of the Red Wall agreed that transgender women should be allowed to use female changing rooms, versus 28 percent who disagreed (36 percent did not know or did not support either suggestion). When it comes to whether schools should teach children about Britain’s colonial past and its role in the slave trade, 73 percent of those in Red Wall seats support this being part of the curriculum, with only 6 percent opposing. More widely across Britain the figures are 78 percent and 4 percent respectively. On climate change, people in the Red Wall overwhelmingly believe that the climate is changing as a result of human activity (72 percent believe this to be the case, 16 percent do not). A big majority also believe that the risks of climate change are not being exaggerated (66 percent).

These figures are close to those recorded from Britain as a whole. They show that the Red Wall residents are very similar to people in the rest of Britain. They are far from a reactionary mob. Of course, even though such statistics help demolish some lazy stereotypes, they do not always show majority support for progressive ideas. Rather, they show that more people support them than oppose them, but also there are large numbers who still need to be persuaded. Ideas are in flux, and, at a time of economic and political crises, people can go to the right or left.

The notion, therefore, that a “culture war” utterly dominates British politics does not fit. We should reject the idea the society is made up of liberals at the top and backwards, uneducated bigots at the bottom. The reality was well expressed by the academic and writer Michael Moran:

The deregulation of financial markets (in New York in 1976, and in London a decade later) was a choice, made because economic and governing elites sensed advantage in the act. Choice created deregulated labour markets and often—as in the case of the miners in Britain—led the state to destroy whole working-class occupations. Choice fashioned taxation systems to enrich plutocrats. Choice positioned Britain as a post-industrial service economy in the international division of labour, where the most important enterprises were branch subsidiaries of foreign enterprises…

In many discussions of populism the “problem” that is posed is assumed to lie in the attitudes and behaviour of “ordinary” citizens rather than in elites. But the betrayal in the broken contract suggests that the problem lies not with “ordinary” people but with abnormal elites. It is elites, not “ordinary” people, who need re-education. But the scale of the problem suggests that re-education alone will not do the job.10

The reality is that sections of workers have always voted Tory. There is nothing automatic about the construction of mass working-class collective consciousness, let alone socialist consciousness. In the 1880s, the great majority of workers who had the vote (only 60 percent of men, and no women) voted for the openly capitalist Liberal Party. Even after the first battles to set up a Labour Party at the beginning of the 20th century, most workers still voted Tory or Liberal. The working class gained a better sense of class solidarity—and, as a side effect, a habit of voting for Labour—due to three waves of struggle. Each involved mass strikes, militant protests and socialist agitation: first, in the late 1880s and the 1890s; second from 1910 to 1926; and third, in the 1930s and during the Second World War. Direct class battles caused more workers to think of themselves as people who have common interests that was sharply different to those of the bosses and Tories. In the 1950s and 1960s, the lack of struggle meant some workers drifted back to voting Tory, and the great class battles of the 1970s had much weaker effect on voting patterns. After all, Labour was in government for 11 of the 15 years between 1964 and 1979. Moreover, the decline in struggle after the defeat of the Miners’ Strike in 1984-5 has had a powerful effect on working-class consciousness.

A wider process

The Hartlepool result and the wider Labour losses are part of a longer-term trend. As the 2019 general election showed, for 25 years Labour has been seeing generally falling support with only occasional increases—principally Corbyn’s extraordinary surge in 2017.11 The recent electoral history of Hartlepool shows this (table 1).

Table 1: Recent labour votes and vote shares in parliamentary elections in Hartlepool

|

Election |

Labour vote |

Labour vote share ( %) |

|

1997 |

26,997 |

60.7 |

|

2001 |

22,506 |

59.1 |

|

2004 by-election |

12,752 |

40.7 |

|

2005 |

18,251 |

51.5 |

|

2010 |

16,267 |

42.5 |

|

2015 |

14,076 |

35.6 |

|

2017 |

21,969 |

52.5 |

|

2019 |

15,464 |

37.7 |

|

2021 by-election |

8,589 |

28.7 |

In 1997, disenchantment with the Tories saw a very big Labour vote in Hartlepool. Anyone who thinks this was down to the candidate—Peter Mandelson—and his policies should note that this was roughly the sort of tally that Labour achieved throughout the 1980s, when its manifestos were more left wing. Moreover, as soon as the experience of New Labour governments hit, the Labour vote started to fall, even if its vote share did not decline as quickly due to an overall falling turnout. The one real moment of hope was Corbyn’s 2017 election campaign. The 2021 by-election was the instant when the underlying decline finally turned into a lost seat, but the roots are far deeper than the last few months and years. This was less a sudden earthquake and more the reaching of a tipping point.

The reality is that social democracy is in real decline not just in Britain but in many other parts of the world. In the week of the May elections, author and academic Matthew Goodwin used recent general election results to calculate that the centre-left vote was at its lowest level in Britain since 1935, lowest in Austria since 1911, lowest in Germany since 1932 and lowest in Sweden since 1908. It was at its lowest ever in France, Italy and the Netherlands, and second lowest in Finland. As he commented: “Maybe it’s not Brexit or Starmer?”12

Modern social democracy’s ability to deliver change is premised on a capitalism that can produce enough of a surplus for a bit to be skimmed off for the masses. But a system in crisis makes the multinationals, banks and bosses far less willing to countenance even small reforms. Only struggle could extract even quite small measures. Nothing of that sort is on offer from the Labour Party, German Social Democrat Party (SPD) or the French Socialist Party.

Today the SPD has no chance of winning the forthcoming elections in September 2021, even though the conservative Christian Democrat Union is facing its own corruption allegations. This is not because it is “too woke”. Instead it is a continuing effect of, for example, the Agenda 2010 programme, implemented by SPD chancellor Gerhard Schröder, that savaged wages and workers’ rights. The SPD fought its own supporters in a war that the right might have shied away from.

Social democratic parties are being battered because they either implemented austerity, particularly after the 2007-8 financial crisis, or because they offer only “austerity-lite” as an alternative. One striking example has been the death of the social-democratic Pasok party in Greece. However, the point is not to seek the resuscitation of forces such as Pasok but rather to create better alternatives, and this requires also going beyond the analysis put forward by the Labour left. For many socialists in Labour the battle is to replay the experience of Corbyn but with a bit more determination. If only, the argument goes, we could return to the possibilities we saw in 2017 but this time chuck out the most awful of Corbyn’s opponents, then electoral success and real change is once again on the agenda.

There are at least four reasons why this approach is not enough. First, Labour’s right wing are determined never to allow someone like Corbyn to be elected as leader again; there will be no risk of right-wing Labour MPs “lending” a left-winger nominations in order to “have a contest”, as they claim to have done during the 2015 leadership race.

Second, like it or not, Starmer won a significant majority in the 2020 leadership election—56 percent of party members—against the mildly left-wing Rebecca Long-Bailey. He won an even bigger majority of 76 percent among the registered supporters, who were crucial to Corbyn’s election as a leader, and he even took 53.1 percent of the votes of the affiliates, mostly trade unions.13 Many party members and supporters liked Corbyn but have accepted the need for someone more “electable”, that is, more right wing.

Third, in practice the Labour left continues to accept the necessity of unity with the right in order to win elections and pass laws in parliament. The response, for example, to Starmer’s attacks on Rayner was to bemoan his failure to welcome all parts of the party into its leadership rather than to recognise that a new course is needed. This acceptance of electoralism and unity is the reason why, despite the constant assaults, figures such as John McDonnell, Diane Abbott and Richard Burgon stay inside Labour. They do this even though Corbyn, Labour’s choice for prime minister in 2019, was first suspended from the party on false claims of antisemitism and then, when reinstated, prevented from sitting as a Labour MP. The left could have stood alongside Corbyn at the local, Scottish, Welsh and mayoral elections. They might have garnered significant support, but they fear they might not win, and they therefore remain imprisoned inside a party whose highest stratas hate them. They have left Corbyn in the wilderness and in practice they are constantly lowering their sights. If Starmer were forced out, the “left” candidate is likely to be someone such as Andy Burnham, who, though having the advantage of not being Starmer, offers absolutely nothing fundamentally different.

Fourth, the real test of Corbyn never came. If he had been elected then he would have faced the ferocious opposition of the banks, the corporations, the international financial institutions and US imperialism. There was no strategy to deal with this—except to make concessions and dutifully attend the conferences of organisations such as the Confederation of British Industry.

Elsewhere, more left-wing forces than Labour have indeed faced the test of office. Two days before Labour saw its 6 May catastrophe, Pablo Iglesias of Podemos in the Spanish state resigned from politics. Podemos once sought to be an expression of the explosive resistance of 2011 and, at one point, was the hope of much of the European left. However, it has faced a choice between staying linked primarily to resistance or prioritising the parliamentary sphere. The party was born amid the exciting resistance of the 15-M movement of occupation of the squares, mass strikes and anti-eviction movements in 2011. It is now in a government coalition with the right-wing social democrats of the Socialist Party, implementing Covid-19 policies that put business interests before workers’ health and denying the people of Catalonia a choice about their future. In Spain’s North African enclave of Ceuta, it is complicit in sending soldiers and police to repulse and batter desperate refuges from neighbouring Morocco.

Igleisias stepped away from a high-profile role after Madrid regional elections that saw Podemos come fifth with just over 7 percent of the vote amid a surge for the right and the far right. Nevertheless, he claimed that he remained “very proud” to have led “a project that changed the history of our country”. What was the nature of this project? One Guardian correspondent certainly knows what it was—Iglesias had “travelled, over the course of a few short years, from being one of the fiercest critics of the ruling elite to one of those at its very heart, albeit only briefly”.14 What a condemnation! Iglesias has followed precisely the road he explicitly rejected a decade ago. His declared mission was to detonate mainstream politics, not to find a niche within it. However, the signs have long been there. Five years ago, he said: “That idiocy that we used to say when we were on the extreme left, that things change in the street and not in institutions, is a lie”.15 Once you make that calculation then you have chosen the route of Syriza, Corbyn and Bernie Sanders—and ultimately of social democracy.

The Labour left will, in the main, direct their energies to a new round of internal battles over policies and procedures. They will insist that the weary battle to win a parliamentary majority within the existing state structures must be restarted. Nevertheless the most potent sources of hope, in Britain and across the world have been outside parliament and against the existing system. The school climate strikes, Extinction Rebellion, the Black Lives Matter movement, the demonstrations against the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill, and the massive marches for Palestine are the future—not clinging to a failed Labour Party.

Yet spontaneity, strikes and struggle in the streets are not enough. In the last two years, we have seen many insurgent movements that came up against the reality that political organisation is needed to carry through revolutionary change. The pro-Palestinian activist and academic Ilan Pappé put this beautifully at a recent meeting of Marxists in Africa. He said he had detected there was “something missing” in the Arab spring and movements such as Occupy, which possessed an “understandable disdain of organisation”. However, said Pappé, “you need organisation.” If you fail to build organisation, “you are like people who have a source of very pure and good water and want pass it on. But, because you dislike containers and bottles, you try to move it with your hands. When you do that, you come away empty-handed”.16 It seems a long way from Hartlepool to 2021’s heady battles in Hebron, Haifa and East Jerusalem, but the need for genuinely revolutionary organisation flows from both.

Charlie Kimber is the editor of Socialist Worker and a co-author of The Labour Party: A Marxist History (Bookmarks, 2019).

Notes

1 BBC News, 2021.

2 Jones, 2021.

3 House of Commons Library, 2021.

4 Curtice, 2021.

5 Mandelson, 2021.

6 Blair, 2021.

7 Mason, 2021.

8 www.jlpartners.co.uk/local-elections

9 YouGov, 2021.

10 Moran, 2019.

11 There is a full description of this process in Kimber, 2020.

13 Labour Party, 2020.

14 Jones, 2021.

15 Bravo, 2016.

16 Africa Marxism, 2021—https://fb.watch/6orjs1Pqa-

References