Antonio Gramsci famously wrote in 1930: “The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear”.1 He was writing about an era of economic depression, rising fascism, and incipient world war. For many, the contemporary world is getting there again.

The results of the German federal elections on 24 September confirmed that the celebrations in the neoliberal centre at the time of Emmanuel Macron’s victory in May were premature. The revolts against mainstream politics continue, although in this latest case it is the racist and populist right that is benefitting. The anti-migrant, Islamophobic, Nazi-apologist Alternative für Deutschland leapfrogged into the Bundestag for the first time with nearly 13 percent of the vote, becoming the third largest parliamentary party.

Meanwhile the combined vote of the parties forming the outgoing grand coalition government, which have dominated the Federal Republic since its establishment in 1949—the Christian Democratic and Christian Social Union bloc (down from 41.5 to 33 percent) and the Social Democratic Party (down from 25.7 to 20.5 percent)—saw their combined share of the vote drop from 60 percent in 2013 to around 53 percent now, their lowest levels ever. Angela Merkel will hang onto the chancellorship, but she is a weakened figure. This will have profound implications for Macron’s efforts to achieve greater economic integration in the European Union, and probably for the Brexit negotiations.

The complacent assumption of the Western ruling classes that they can continue squeezing living standards and avoid any political comeback has suffered another blow.2 The AfD’s support was strongest in economically depressed areas in eastern Germany. The reformist left can’t escape their share of the responsibility for this catastrophe: the social-liberal SPD lost 470,000 voters to the AfD and the more radical Die Linke 400,000.3 Like the attempts by American Nazis to mount demonstrations in cities such as Charlottesville, Virginia, over the summer and the much more powerful counter-protests, the AfD’s advance underlines the urgency of building mass anti-racist movements to reverse the rise of the fascist and populist racist right.

***

But few symptoms could be more morbid that the president of the United States appearing before the General Assembly of the United Nations—an organisation ostensibly dedicated to world peace—and threatening “to totally destroy North Korea”.4 Here we see the internal political strains of the advanced capitalist societies—Donald Trump is the beneficiary of another populist revolt—spilling over into the international arena. The crisis in the Korean peninsula marks a potential collision course between developing inter-imperialist contradictions and the erratic foreign policy the US is pursuing under Trump.

North East Asia is becoming the most important zone of global capitalism, the site of three major economies—China, Japan and South Korea. But it could also be the battleground of the world’s first nuclear war, embroiling these countries along with the US and North Korea as the main antagonists. Bruce Cumings, the leading American historian of modern Korea, writes:

American atmospheric scientists have shown that even a relatively contained nuclear war would throw up enough soot and debris to threaten the global population: “A regional war between India and Pakistan, for instance, has the potential to dramatically damage Europe, the US and other regions through global ozone loss and climate change”.5

The Korean peninsula has long been a site of inter-imperialist conflict, though the configuration of rivalries has changed in the past two decades. The origins of these struggles lie in the 1940s, though Korea’s subordination to outside powers dates back to 1905, when it was seized by an ascendant Japanese imperialism. The prestige of the ruling Kim dynasty in North Korea (officially the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, or DPRK) originates in the role of its founder, Kim Il-sung, in leading Communist guerrilla struggles against the Japanese occupation of Manchuria between 1932 and 1945. According to Cumings:

This is the source of the North Korean leadership’s legitimacy in the eyes of its people: they are revolutionary nationalists who resisted their country’s coloniser; they resisted again when a massive onslaught by the US air force during the Korean War razed all their cities, driving the population to live, work and study in subterranean shelters; they have continued to resist the US ever since; and they even resisted the collapse of Western communism—as of this September, the DPRK will have been in existence for as long as the Soviet Union.6

At the end of the Second World War, Korea was occupied by the two new superpowers, the US and the USSR. As a result, it became the site of one of the most savage wars of the Cold War era, in which over 3 million Koreans died, particularly as a result of devastating and indiscriminate bombing by the US and its allies.7 This conflict developed from a civil war between the two client regimes—in the North under Kim Il-sung, in the South under Syngman Rhee, but seems to have been precipitated by complex manoeuvres in the Stalinist camp. Stalinist Russia played a founding role in establishing the DPRK. As in Central and Eastern Europe, the Soviet occupiers imposed state capitalist political and economic forms in the North and suppressed popular movements.8 According to one interpretation, Stalin gave Kim the green light to attack the South in June 1950, in the hope of gaining warm-water Pacific ports at Inchon and Pusan, but also with the aim of locking the newly established People’s Republic of China into the Soviet camp.9

In the event, as the US commander Douglas MacArthur drove the Western advancing forces ever closer to the Chinese border, with the aim of reunifying Korea under US dominance, the People’s Liberation Army decisively intervened. A joint Chinese-North Korean counter-offensive in November-December 1950 sent the US and its allies into flight down the peninsula. The war ground down into a stalemate ended in 1953 by an armistice that more or less maintained the original partition of the country in 1945. But there was no peace settlement between the two Korean regimes, which remain in a state of highly armed hostility, facing each other across the Demilitarised Zone separating their territories.

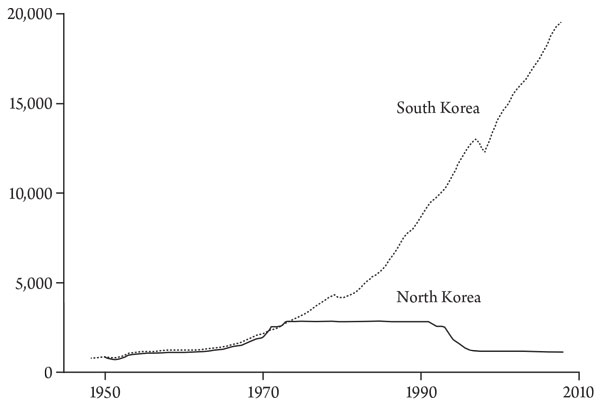

There have been two major shifts in the relations of forces on the peninsula. The first was the growing economic divergence between North and South. Both states were devastated by the war. Both grew modestly till the 1970s, with the North enjoying the advantage that it had been preferred for industrial investment by Korea’s Japanese colonial rulers. Thereafter their paths diverged dramatically, with national income per head rising spectacularly in the South and first stagnating and then, after the 1990s, dropping sharply in the North (see figure 1). Under the military dictatorship of Park Chung-hee (1961-79), and building on the foundations laid under Japanese colonial rule, the South Korean state, with generous patronage from the US and from Japanese capitalism, steered its favoured businesses into producing for selected export markets. This marked the beginning of a process of rapid (though unstable) expansion that has made South Korea the 11th largest economy in the world, with a leading position in industries as diverse as shipbuilding, semiconductors and smartphones.10

Figure 1: North and South Korean GDP per capita, 1947-2007.

Source: https://twitter.com/SevaUT/status/902217278103719936

While South Korea industrialised rapidly through selective integration in the world market, the DPRK under Kim Il-sung constructed an extreme version of the bureaucratic state capitalism already developed in the USSR and China. The distinctively North Korean version of the Stalinist conception of Socialism in One Country, dubbed juche, or self-reliance, was introduced by Kim in the mid-1950s as he tried to take the DPRK on a path independent of both the Soviet Union and China while still confronting the US, and therefore to drive up the growth rate by prioritising accumulation in heavy industry at the expense of living standards. What became a dynastic form of rule with Kim Il-sung (1948-94) followed by his son Kim Jong-il (1994-2011), and then his grandson Kim Jong-un (2011-), emerged from the factional struggles within the ruling party over whether to remain aligned with the Soviet Union, tack towards China, or take an independent path.11

The relatively sympathetic Cumings says the “North Korean system” was “put in place to insulate the nation against the disasters of colonisation, depression and war”. Writing during the 1990s, he described it as:

not simply a hierarchical structure of party, army, and state bureaucracies (although it is that) but also a hierarchy of ever-widening concentric circles… At the centre is Kim.

The next circle is his family, the next guerrillas who fought with him, then come the party elite… This…core circle…controls everything at the commanding heights of the regime… As the penumbra of workers and peasants is reached, trust gives way to control on a bureaucratic basis.12

The DPRK survived when most Stalinist regimes were swept away. During the Cold War Kim Il-sung skilfully manoeuvred between the two, increasingly antagonistic Communist giants, the USSR and China. The collapse of the Soviet Union (which accounted for three fifths of North Korea’s total trade in 1988) caused the North Korean economy to shrink by 30 percent in 1991-6.13 A combination of catastrophic floods and the disruption of a highly industrialised agricultural system by the cut-off of cheap Soviet energy imports led to a terrible famine in 1997-9; estimates of the cost in human lives vary between 200,000 and 3.5 million.14

But the North Korean state did not collapse. Indeed (contradicting the stereotypical image of a closed “Hermit Kingdom”), it survived partly by relaxing controls, allowing peasants to sell food produced on their private plots and tolerating the growth of cross-border trade with a booming China. This process of controlled marketisation has accelerated under Kim Jong-un. According to the Financial Times, Kim has promoted:

gradual market-based reforms that have led to swift growth in private enterprise and an uptick in the standard of living that defies western preconceptions about the erstwhile Stalinist state, according to a host of North Korea experts, intelligence sources, former residents and business visitors.

“North Korea has gone from a very tightly controlled state socialist economy to basically a marketising economy,” says Sokeel Park of Liberty in North Korea, a group which helps scores of people defect every year… Wages have also appeared to increase exponentially in recent years. According to the [Korea Development] institute, salaries in the official state sector have increased more than 250 percent in the past 10 years to about $85 (more than 75,000 North Korean won) a month, while wages in unofficial “side” jobs, such as private enterprises, have boomed more than 1,200 percent.15

Daniel Tudor and James Pearson, two Western journalists, describe a two-tier system in which nominally the economy is state controlled and the population live off their (tiny) state salaries and rations and an illegal but semi-tolerated market economy that expands progressively. This second economy is driven by a network of small traders and fuelled by remittances from North Korean defectors now living in the South that are very efficiently transferred to their families via China. They call the result “public-private capitalism”, where entrepreneurs use political connections to set up nominally public companies and top party officials, including the Kim family itself, enjoy generous rake-offs from the profits.16

This peculiar version of crony capitalism is facilitated by the clandestine economic operations that the regime relies on to circumvent the sanctions imposed by the US and (to varying degrees) the rest of the “international community” and to gain access to foreign currency (preferably euros or renminbi). This extends from arms trading to smuggling rhino horn and ivory in Africa.17 But the degree of marketisation can be exaggerated. North Korea’s resources (including the labour force) are still not allocated according to market signals and the share of the economy regulated primarily by market mechanisms is still small. The new merchant capitalists lack autonomy thanks to their dependence on state bureaucrats. And it’s possible the limited changes that have taken place could be rolled back when the political leadership chooses in response to changes in the political situation.

What is certain is that both the Kim regime and ordinary North Koreans have relied heavily on the DPRK’s extraordinarily strong economic connection with China. In 2015 China accounted for 85 percent of North Korea’s imports and took 83 percent of its exports.18 This then takes us to the second major change in the relations of forces. North Korea’s economic dependence on China reflects the exposed position the Kim regime found itself in after the collapse of the Soviet Union. China was now its only backer. But China’s position has also changed profoundly in the past 25 years. A close ally of the US against the USSR in the final decades of the Cold War, China, thanks both to its extraordinary economic expansion and to the ambitions of its leaders, is now the major challenger to US hegemony—in the first instance in the Asia-Pacific region, which is becoming a cockpit of interstate rivalries, but implicitly globally as well.19

Moreover, since the outbreak of the economic and financial crisis Beijing has become much more assertive regionally, most notably clashing with Japan over the Senkako/Diaoyu islands and buttressing its claim to the South China Sea by transforming tiny atolls into fortified islands. Border frictions with India have also been growing recently over areas that fell under British suzerainty during the eclipse of the Chinese Empire in the 19th century. Simultaneously China is exercising economic leverage to pull states such as Cambodia and the Philippines into its orbit. Any change in the Korean peninsula has to be assessed in the light of these shifting relationships. South Korea has growing economic and cultural links with China, with whom it shares bitter memories of Japanese imperialism, but remains locked into military alliance with the US. If North Korea collapsed and were absorbed by the South, in the way West Germany swallowed up East Germany in 1989-90—which seemed a serious prospect in the 1990s, then Beijing would find a powerful US ally on its border.

This calculation has given China a relatively strong incentive to prop up the North Korean regime. But the Kims have not been content to rely on Chinese benevolence. The nuclear programme that probably started in the early 1990s and that has now developed to the point where North Korea is drawing close to the ability to launch intercontinental ballistic missiles armed with nuclear warheads is intended to provide the regime with an insurance policy against any US-instigated attempt at regime change. This is a monstrous policy, but—contrary to the various Western denunciations—it is not irrational from the perspective of the North Korean leadership. In January 2002 George W Bush named North Korea, along with Iraq and Iran, as one of the “axis of evil” of “rogue states” threatening the world with their weapons of mass destruction. Saddam Hussein notoriously had no WMD and paid with his life after the US-British invasion of Iraq. The Bush administration seriously contemplated war with Iran as well. But North Korea vanished off the neocon agenda—Kim Jong-il really did have WMD.

US denunciations of North Korea for “introducing” nuclear weapons into the Korean peninsula are thoroughly hypocritical. After the Chinese counter-offensive of November-December 1950 sent his forces into flight, MacArthur panicked and argued for the use of nuclear weapons, a move that was seriously contemplated in Washington. MacArthur’s histrionic grandstanding eventually led to his dismissal by President Harry Truman, whose Republican successor Dwight Eisenhower cut the deal with Kim Il-sung that ended the war. But it was also under Eisenhower that the US introduced hundreds of tactical nuclear weapons into South Korea in 1958-9. American war planning right up to the 1980s provided for the early use of nuclear weapons in the event of a new conflict with the North.20 These weapons were only withdrawn after the end of the Cold War, but Washington maintains 28,000 troops in the South and of course has plenty of nuclear-capable forces near at hand.

For the US what is at stake is trying to shore up its overwhelming predominance in nuclear capabilities globally—and ultimately removing an obnoxious regime. For the Kim dynasty and its retinue it is survival. Pyongyang has become skilled in a game of brinkmanship around its nuclear programme, and has confounded the experts in the speed with which it has upgraded its capabilities. Apart from long-term security, the regime’s aim is probably partly to counterbalance the conventional superiority enjoyed by the combined US and South Korean forces, which regularly conduct massive and threatening military exercises, and partly to achieve its major diplomatic goal of direct negotiations with Washington.

Cumings scathingly summarises the bankruptcy of US policy towards the North:

Since the very beginning, American policy has cycled through a menu of options to try and control the DPRK: sanctions, in place since 1950, with no evidence of positive results; non-recognition, in place since 1948, again with no positive results; regime change, attempted late in 1950 when US forces invaded the North, only to end up in a war with China; and direct talks, the only method that has ever worked, which produced an eight-year freeze—between 1994 and 2002—on all the North’s plutonium facilities, and nearly succeeded in retiring their missiles.21

Trump has, of course, talked up another option—war with North Korea. He is by no means the first US president to do so, but successive administrations have always backed away. Of course, North Korea would indeed be “totally destroyed” in an all-out war, but probably not before it was able to mount nuclear strikes on Japan and, if not on the continental US in the short term, then on American Pacific bases in places like Guam and Okinawa. The North would also lose a conventional war, but also at a terrible price. There is no doubt an element of anti-Communist paranoia in this report of the results of Pentagon war games, but it is still scary:

Like the Imperial Japanese Army in World War II, the North will seek a decisive battle that, in its view, could knock out a weak-willed United States. That means a massive barrage in the first few hours of the conflict, targeting the largest US military garrisons along the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) and in the Seoul region. Other targets could include air and naval bases in the South, and possibly Japan, to prevent an allied counterattack and soften defences for a possible entry by the North Korean military along the DMZ or via small-scale amphibious landings in the east and west. Pyongyang will fire short-range ballistic missiles and multiple rocket launchers near simultaneously to destroy these few dozen high-value defence infrastructure targets.

Although estimates vary, some figures indicate that North Korea has approximately 1,000 missiles positioned across the country and most of them within reach of Seoul… In the event of a war, North Korea will not hesitate to launch chemical and biological weapons at South Korean and US air bases or on main supply routes. A biologically or chemically contaminated site would have to be treated with special care, requiring all forces in the area to don protective gear and severely disrupting South Korean and US movements across the battlefield… Decentralised attacks could also be in the cards, as North Korea has reportedly recruited hundreds of spies across the world to conduct various missions. Those agents would likely be blended into the larger North Korean population and could be activated to carry out attacks using weapons of mass destruction in the South…

Whether confined to conventional artillery or supplemented by unconventional warfare, within the first few hours of the conflict, tens of thousands of people will be dead and large swaths of Seoul in smouldering ruins. The South Korean capital is one of the most densely populated places in the world; some 43,000 people live in each square mile of the city.22

This report underlines one of the most frightening features of any new Korean war, nuclear weapons aside. Seoul, a world city of over 10 million inhabitants, the symbol of the South’s ascent, situated very close to the border between the two Koreas, is essentially the North’s hostage, and has been for decades. This reality alone is a very powerful deterrent against any attempt by the US to attack the DPRK. This has constrained the response by successive administrations in Washington to Pyongyang’s nuclear programme.

Two interrelated factors have complicated the situation—Trump, and growing US-China competition. Trump denounced America’s wars in the post 9/11 era during his election campaign, but in office he was authorised greater US military involvement in the Greater Middle East, most notably in his recent announcement that more troops would be sent to Afghanistan. No doubt this has a lot to do with the leading positions in his administration occupied by military men (defence secretary James Mattis, national security adviser H R McMaster, and now White House chief of staff John Kelly). But belligerence also feeds Trump’s self-image as a strong decisive leader unlike wimps like Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton.

This doesn’t mean Trump wants war with North Korea (and almost certainly his generals don’t). Back in May he said he would be “honoured” to meet Kim Jong-un personally, “in the right circumstances”.23 Since taking office Trump has concentrated on pressuring China to impose comprehensive sanctions on the DPRK. This plays into his erratically pursued policy of squeezing China economically—for Stephen Bannon, his sacked but still influential adviser, “the economic war with China is everything”.24 So not surprisingly, Beijing’s response to Trump’s unsubtle pressure has been less than enthusiastic. This doesn’t mean the Chinese leaders are giving Kim Jong-un a blank cheque. The murders of the Kim family members said to be closest to China (Kim Jong-un’s uncle Jang Song-thaek and his half-brother Kim Jong-nam) seem to have reduced its access to the innermost circles in Pyongyang. In any case relations between China and North Korea under Stalinist rule have never been easy. Kim Il-sung’s slogan of juche was directed at Beijing as well as Washington and Moscow.25

The shock-waves from North Korea’s thermonuclear test in August were felt widely in northern China, and there is growing concern among ordinary citizens about the environmental consequences of the DPRK nuclear programme. It might, moreover, provoke South Korea and Japan to develop their own nuclear capabilities. This new regional arms race would almost certainly work to Beijing’s strategic disadvantage. But the Chinese leadership still prefer the DPRK’s survival to its annexation by the South and is fearful of the refugee crisis that the violent fall of the Kim regime might create on its borders. As James Person puts it, “the collapse of North Korea would be a national security nightmare for China, bringing a US treaty ally to its doorstep at a time when Beijing aspires to reassert its regional hegemony in East Asia”.26 So China has progressively tightened sanctions, but not to the extent of, for example, cutting off the oil tap.

Trump has reacted to this (from his perspective) inadequate response by targeting specific Chinese firms deemed by Washington to be helping North Korea. But it is probably his belligerent rhetoric—for example, the UN speech and the tweet threatening that the Kim regime “won’t be around for much longer”—that is most dangerous.27 A dynasty that sees itself fighting for its survival might take this bluster seriously (while Trump was soon happily tweeting attacks on African-American football players who refuse to stand for the US national anthem). In a situation where both sides are undertaking dangerous military manoeuvres—Pyongyang threatening more tests and Washington sending its bombers close to North Korean airspace, a miscalculation could precipitate disaster.

One potential blockage on this road to catastrophe is the people of South Korea themselves. Over the past 15 years there has been a succession of mass movements at least in part aimed at the continuing US presence in South Korea, and culminating in the removal earlier this year of President Park Geun-hye, the daughter of the old military dictator. The new South Korean president, Moon Jae-in, is clearly under immense popular pressure to moderate Trump’s confrontational stance. If the South Korean mass movement impose their veto on the drive to war, the whole peninsula can contemplate a happier future.

The Korea crisis underlines the persistence of imperialist domination globally and of the rivalries among capitalist states. These afflict other parts of the world—for example, Syria, Libya and Yemen in the Middle East. But nowhere are they more toxic than on the Korean peninsula. This underlines the urgency of building a movement that can not simply stop individual wars but put an end to the entire system of capitalist imperialism.

Alex Callinicos is Professor of European Studies at King’s College London and editor of International Socialism.

Notes

1 Gramsci, 1971, p276; Gramsci, 1975, I, p311 (Q3 §34). I’m grateful to Camilla Royle and the comrades of Workers Solidarity in South Korea for their comments on this article in draft.

2 For the economic background to the German election, see Roberts, 2017.

4 Go to www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2017/09/19/remarks-president-trump-72nd-session-united-nations-general-assembly

5 Cumings, 2017.

6 Cumings, 2017.

7 Halliday and Cumings, 1988.

8 Kim, 2006a.

9 Shen, 2012. This study by a Chinese scholar using extensive archival research supports the interpretation I remember Tony Cliff putting forward more than four decades ago on the basis of an analysis of the logic of the situation.

10 Useful discussions of the origins of South Korean industrialisation will be found in Cumings, 1984, and Chibber, 2003. The latter period of Japanese colonial rule marks the start of this process because the Japanese state sought in the 1930s to construct a transnational economy in which dependencies such as Korea and Taiwan and conquered territories such as Manchuria and northern China would participate in an imperial division of labour—see Beasley, 1987. This involved, for example, establishing an important chemical plant in the North.

11 See the outstanding Marxist analysis by Kim Ha-yong, summarised in English in Kim, 2006a and 2006b.

12 Cumings, 1997, p409.

13 Noland, 1997.

14 Woo-Cumings, 2002.

15 Harris, 2017.

16 Tudor and Pearson, 2015.

17 Pilling, 2017.

18 Holodny, 2017.

19 Kim, 2013, and Callinicos, 2014.

20 Cumings, 1997, pp288-293, 477-483.

21 Cumings, 2017.

22 Peddada, 2017.

23 Wilts, 2017.

24 Kuttner, 2017.

25 Person, 2017.

26 Person, 2017.

27 https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/911789314169823232″ rel=”noopener” target=”_blank”>https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/911789314169823232″>https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/911789314169823232

References