The election of Donald Trump as president of the United States crystallised fears among sections of the financial elite that the world economy was beginning to spin towards a new era of protectionism. During his campaign Trump used rhetoric that echoed right-wing populist parties elsewhere in the developed world. In its most virulent form, trade protectionism was conjoined with anti-immigrant discourse aimed at Mexicans and other Latinos “south of the border”. The message was designed to appeal to workers disaffected and distanced from the neoliberal elite whose free trade policies had supposedly caused job losses as employers sought cheaper labour abroad. The message worked for Trump, as the Democrats had no place to hide from the suggestion that they were to blame.

Since he took office, Trump’s tilt towards protectionism has caused a row within Washington. He has withdrawn the US from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (aimed at competition with China) and plans to renegotiate the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and to drop the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) between the US and the European Union. According to one source the disagreements are akin to “a civil war…within the White House over trade, leading to what one official called ‘a fiery meeting’ in the Oval Office pitting economic nationalists close to Donald Trump against pro-trade moderates from Wall Street”.1 Writing in the Financial Times in May 2017 Martin Wolf states that Trump “appears to be intent on replacing multilateralism with bilateralism, liberalism with protection and predictability with unpredictability”.2

These divisions over strategy will not go away soon. One of Trump’s first moves as president was to establish a White House National Trade Council under the directorship of Peter Navarro, the author of the book Death By China, which takes aim at US-China trade policies. The substance of the new policy is “repatriation” of international supply chains (especially those involving China) and the construction of alternative “domestic” supply chains within the US.3 Trump’s decision on 2 June 2017 to pull out of the Paris Climate Agreement was also dressed up by him as a defence of “Pittsburgh” rather than Paris, suggesting a deepening of a long strand of Republican “isolationism” cloaked with economic nationalism.4 Parallel to these moves Trump has raised possibilities of new trade deals with the EU (outside TTIP), and indeed with China. This ambivalence and ambiguity in Trump’s agenda suggests that, rather than pure destruction and retreat into protectionism, a re-ordering of trade arrangements is under way.

The new vogue of trade protectionism, which lies like a shadow over Trump’s policies, also reflects those of right-wing populists and fascists in Europe such as France’s Front National. The protectionist mindset sits side-by-side with the proposition that we have now entered a period where globalisation as we know it is at an end. Indeed, suggestions of globalisation’s demise began more than a decade ago, after 9/11, identified by some commentators as the end of the new liberal world order promised by Francis Fukuyama in his 1989 essay “The End of History?”.5 The “end of globalisation” thesis thus runs as a follow-up to the “end of history” nirvana promised by the Fukuyamists.

The conservative historian Niall Ferguson has been prominent in the debate.6 Ferguson equates contemporary political developments with that of the period at the beginning of the 20th century, when an earlier period of “globalisation” collapsed into war and economic nationalism. His approach is affirmed by the work of John Ralston Saul, who has suggested that after 1995 (his considered “high-point” of globalisation) nationalism and ethnic and religious fundamentalism have all but destroyed the dream of a liberal world order and accentuated division in the political and economic spheres.7

Outside this essentially conservative political assessment has been a more measured economic critique, most notably by Paul Hirst and Grahame Thompson in their 1999 book Globalization in Question.8 The book articulated doubts about the “hyperglobalisation” thesis predicting the end of the nation state, by pointing out that the overwhelming majority of foreign direct investment (FDI) was not between Global North and South but was exchanged between the rich nations, and more often than not within the same corporations over national boundaries. However, what we are seeing now is a new period of doubt and caveat on the efficacy of globalisation, spurred by economic data showing a reversal of trends from previous decades.

Indeed, doubts about globalisation now also come from the left, including people such as James Meadway, consulting economic advisor to the UK’s shadow chancellor John McDonnell, who has called for a programme of state-led infrastructure investment to offset the end of globalisation.9 Others on the left, such as Wolfgang Streeck, write from a perspective of despair about the rise of “Trumpism” and its national/populist European equivalents as a consequence of the collapse of the “centre-left” project of market-based global internationalism. Streeck writes:

In the 1990s, the centre-left placed its hopes for restoring growth and consolidating public finance on liberalised international markets. A worldwide effort at industrial and social restructuring followed. International competition put pressure on national economies to become more efficient… The bitter medicine did not work; nor was the centre-left granted political immunity. In all countries of the developed capitalist world, the number of losers increased until political entrepreneurs sensed their opportunity and entered the public scene.10

So what is the balance sheet of trends in globalisation? To answer this question we look first at some statistical trends and then trace the political economy of globalisation past and present.

Trends in globalisation

In purely structural and economic terms (rather than cultural or political) we can suggest that the world economy is in a phase of “globalisation” when the rate of growth of world trade is greater than the rate of growth of world production of goods and services. Such a positive ratio would indicate that the world economy is becoming more integrated, as cross-border trade and foreign direct investment increasingly replaces or substitutes for production of goods and services for the home market. When the trend reverses, it generally indicates a period of protectionism and import substitution. This was the case in the inter-war years, when tariffs were raised and exchange controls were imposed in a period of economic nationalism that began in 1914 as geopolitical tensions between the Great Powers accelerated. It took a practical form not only in the Great War but also in its aftermath. Between 1913 and 1950, world trade grew at only half the pace of world output of goods and services, indicating the severity of the retrenchment that fed the Great Depression and then the Second World War.11

However, after 1945 we see a change in the world economy towards more integration. From 1949 until the financial crash of 2008 global trade grew on average at 10 percent per year, outstripping growth of world production by about twofold.12 The reversal in fortunes in the immediate post-war period was clearly a response to US political and economic strategy to reconstruct the capitalist order outside of the Soviet bloc. It was the political engine of war and then the Cold War from which emerged first the Bretton Woods agreement to create a world financial system conducive to open trade and investment and then the Marshall Plan to reconstruct (Western) Europe. The variations and developments of the ensuing “peak” globalisation are discussed later but generally the world economy expanded in parallel with the globalisation of goods and service production and trade.

One feature of increasing importance to the debate is the gathering convergence in incomes and wealth of many far eastern economies with those of the “West”. This convergence began in the 1980s with the rise of Japan, and has since been followed by the growth of South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore and now China. As Martin Wolf again reports,

The most important transformation of recent decades has been the declining weight of the high-income countries in global economic activity. The “great divergence” of the 19th and early 20th centuries, when today’s high-income economies leapt ahead of the rest of the world in terms of wealth and power, has gone into remarkably rapid reverse. Where once there was divergence, we now see a “great convergence”. Yet it is also a limited convergence. The change is all about the rise of Asia and, most importantly, of China.13

It is this “threat from the east” that appears to have spurred not only a revision of perspective of the nature of contemporary globalisation, but also a retrenchment of sections of the US elite into a protectionist stance.

Since 2008, however, the process of expansion appears to have been reversed. There was an upturn in world trade in 2010 as the world economy began to recover but since then trade growth has again slowed down massively and settled to around 2.5 percent per year. World production figures, measured in GDP, have also slowed down since the crash and are also now stabilising with growth rates well under 3 percent by 2015,14 less than 2 percent in the developed economies.15 More significantly, the data indicates a levelling off and then sporadic fall of both global trade and overseas financial assets (of major economies) as a proportion of aggregate world GDP since 2008.16 This retrenchment appears to have been triggered not only by the financial crash of 2008, which has made investors more risk averse, but also by the slowing down of economic growth in East Asia, particularly China, which had acted as an engine of both imports and exports within the wider world economy.

In fact the crash exposed major weaknesses in the neoliberal global business model. Declining rates of profit on investment had stemmed world economic growth, while money shifted into financial speculation eventually burst its own bubble. Since the crash new data have cast doubt on the continuing efficacy of globalisation as an irresistible phenomenon. Free trade, low or non-existent tariffs, and liberal market rules are all part of what we understand as modern-day globalisation. If the tide of economic growth were to be reversed we would expect over four decades of “globalisation” also to peter out. This indeed is the view of the authors of a very influential article in March 2017 in the Wall Street Journal entitled “Whatever Happened to Free Trade?”. The article followed fashion and linked a decade of economic retrenchment to an upsurge in populism. The authors point to the slowdown both in world trade volumes and foreign direct investment (FDI) since the 2008 financial crash, and refer also to the 7,000-plus protectionist measures that have been enacted within the world economy since 2009, “half of them aimed at China”. Capital controls across borders had also become more severe:

In all, 31 out of 108 countries tracked by economists Menzie Chinn and Hiro Ito became less open to global capital flows between 2008 and 2014, while 13 became more open. That’s a sharp reversal from the five-year pre-crisis period, when 40 countries became more open to global capital flows and 12 became less open.17

Similar patterns can be observed with flows of finance capital across borders. The rate of growth of “financial globalisation” has certainly proceeded at a greater rate than trade growth in recent decades, but as the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) reported in 2012:

After having surged to unprecedented levels in 2007 and until mid-2008, private capital flows towards developing countries came to a sudden stop or even reversed direction as the system went into cardiac arrest, fleeing back towards the core countries of global finance that were the epicentre of the crisis.18

A recovery in flows was evident for a short period in 2009, but this again stalled as concerns spread about the volatility and security of the euro within the EU’s debt crisis.

We can point to other indicators. For example, the post Second World War period of “peak” globalisation has also been associated with an expansion of production networks and supply chains as enterprises in the Global North sought cheaper labour areas to exploit in the South. However, there is emerging evidence that the rush in the last few decades to expand global supply chains and to outsource production across world networks has also slowed down and in some cases gone into reverse. Some large corporations, such as US clothing firm American Apparel and Spanish retailer Zara, have focused on domestically based product hubs rather than global supply chains, a model which is now being adopted by others such as IBM in computers and Caterpillar in agricultural machinery. These latter companies used to spread production across the world and are now switching back to a system of production based on “vertical integration”.19 This assumes a much closer geographical link between research and development (R&D) and production facilities whereby consumer market trends can be more quickly and easily accommodated. Companies switching to this business practice are now reshoring production, often alongside changes in labour practices that may include a new phase of automation.

Trends towards reshoring, however marginal, have also been matched with a decline in world totals of FDI. According to the latest OECD reports, FDI flows decreased by 7 percent in 2016, dropping to 2.2 percent of global Gross Domestic Product (GDP),20 a drop to half the rate during the decades of “peak globalisation”. Some of this decline is undoubtedly due to economic caution among investors following the financial crash, but the OECD also point to evidence of nation states citing security concerns as a reason for adding more restrictive measures on both outward and inward FDI. An OECD background note in March 2017 reported that:

Governments are increasingly concerned about the potentially non-commercial objectives of investments by state-owned enterprises or sovereign wealth funds and about the lack of potential reciprocity in terms of the market for corporate control in the country of the investor. Multinational enterprises may also face a resurgence of restrictions on outward investment from their home country.21

Such sentiments would seem to match the desire of Trump and others for a new period of economic nationalism, triggered in part by wider geopolitical concerns of competition from China, which is now a net exporter of FDI.

All this indicates that globalisation may have already had its day in the sun. But if this is the case, how sustainable is the trend away from globalisation? And what are the underlying causes and changes in political economy that have driven these changes? It would be a mistake to view globalisation and its future purely through a statistical lens. Deeper political and economic forces underlie the surface changes found in the statistics, and it is to these deeper forces that we need to turn to develop our understanding. Before doing so, however, we need to consider the history of “industrialised” globalisation, and to learn from its pattern of behaviour.

Globalisation past

The colonial system ripened trade and navigation as in a hot-house. The “companies called Monopolia” (Luther) were powerful levers for the concentration of capital. The colonies provided a market for the budding manufactures, and a vast increase in accumulation which was guaranteed by the mother country’s monopoly of the market. The treasures captured outside Europe by undisguised looting, enslavement and murder flowed back to the mother-country and were turned into capital there.22

In this passage Karl Marx highlights the developing relationship between the forces of empire and trade and capitalism’s need to appropriate funds for further expansion.23 He was writing as Britain had created its empire from the primitive accumulation of capital based on slavery and plunder of its colonial “possessions”. The competitive advantage that Britain and other European powers enjoyed (together with the US after the Great Depression of 1870-80) was utilised to its maximum to fund the coffers of corporations and the state. Technological advances, with the introduction of the telegraph and steamships aided the process. The system of colonial dispossession was based on trade advantage that, although presented as “free” by its apologists, was an expression of economic power backed by military boots on the ground and the Royal Navy at sea. As Friedrich Engels observed of the contemporary scene: “Political economy came into being as a natural result of the expansion of trade, and with its appearance elementary, unscientific huckstering was replaced by a developed system of licensed fraud, an entire science of enrichment”.24 Indeed, as John Newsinger describes in his book The Blood Never Dried, during the opium wars in China “the British Empire was the largest drug pusher the world has ever seen”.25

While trade was the driving force of this earlier period of industrial “globalisation” it was not conducted on a basis that would boost the industrial economy of the colonies. The world’s industrial working class remained firmly rooted in the advanced nations. Slavery was utilised for purposes of primitive accumulation, and the colonies were exploited for their country specific commodities (tea, cotton, sugar cane, etc) and raw materials (such as rubber) rather than their industrial labour power as in our modern period of “peak globalisation”. The search for raw materials and commodities threatened to cause inflation as supplies were finite, and so plunder, extortion and theft became the normal behaviour of the richer colonialists while the living standards of the dispossessed were deliberately suppressed. The financial surpluses extracted through colonialism aided and abetted capital accumulation through the extraction of ever more surplus value from waged workers in new and existing factories in the homeland. The imperialist projects of the Great Powers were thus a fusion of capitalist expansion and territorial gain. The colonies were simply left behind and sometimes pushed back in the process. Indeed, just taking the case of India, as Mike Davis observes, “there was no increase in India’s per capita income from 1757 to 1947”.26

More generally, what we see is that the industrialised world of western Europe and the US leapt ahead in terms of production and GDP per head during this time, leaving the colonised world behind. In 1750 the southern and eastern continents had accounted for 73 percent of world manufacturing production, its share fell to 50 percent by 1830 and by 1913, at the end of the first wave of globalisation, its share stood at just 7.5 percent.27 This is important to note. Liberal historians and conservatives like Ferguson will persist in portraying empire as benign and benevolent, when, as Davis has portrayed in Late Victorian Holocausts, the British, Japanese and US empires left a legacy of dreadful famine and poverty akin to “cultural genocide”. The violence of the period is its key feature, and was made necessary to defend the empire from revolt and insurgency. Britain, of course, was not alone in committing imperialist atrocities and expanding its territory. As Eric Hobsbawm has written, the “Age of Empire…was essentially an age of state rivalry”.28 Within this rivalry the plunder was absolute. In the scramble for Africa over a 30-year period between 1880 and 1910, 110 million Africans became subjects of five European empires, that of Britain, France, Germany, Italy and Portugal plus the Belgian monarch. By the turn of the 19th century British dominance had begun to fade and by 1913 the four chief economies were the US (providing 46 percent share of industrial and mining production, including construction), Germany (23.5 percent), Britain (19.5 percent), and France (11 percent).29 Hobsbawm described this emerging variegation in power as a period of “growing pluralism” of the world economy that began to gather pace at the turn of the century. Britain’s share of all exports from Africa, Asia and Latin America fell from one half in 1860 to one quarter by 1900, creating a world that was no longer “monocentric”.30 But then, as today, Britain did not suffer too much from its relative decline in world trade share, as it found a new role as the world economy’s banker and insurance broker in the City of London. Its previous position of domination had left it with considerable overseas assets and in 1914 Britain still held 44 percent of all world overseas investments.31 But the resulting geopolitical tensions caused by the scramble for Africa and other parts of the world became like a pressure cooker of geopolitical tension. The quarrels between the Great Powers culminated in retrenchment into protectionism followed by the Great War and then two decades of economic turmoil.

From this overview we can distinguish three pertinent features that have shaped globalisation in the past, and which may offer us insights into its present dilemmas and the future. The period of Pax Britannica crystallised after the industrial revolution and in the aftermath of Britain’s victory in the Napoleonic Wars. Britain was subsequently placed as the monocentric hegemonic power throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. However, this power became threatened by new entrants to the game, as state rivalry and polycentric tendencies emerged. The political state rivalry, the pursuit of economics by other means, eventually led to a breakdown of the world system, war and recession. Second, we must note that far from being consensual, or benign, or benevolent, the process of globalisation was violent, entailing famine, murder, torture and the use of state military power to guard against revolt and rebellion. Third, we can note from Marx’s and Engels’s writings on the first wave of “globalisation” that the process of trade expansion and colonisation was integral to the structural development of capitalism at the time. Their description of “Political Economy” flowed from their analysis of why capital needed to plunder outside its industrial heartlands to accumulate.

Our task is now to determine if these three key features of the earlier period of globalisation can aid our understanding of the stability or fragility of the neoliberal order and its own particularised project of globalisation. Most importantly, as capitalism continues to falter with a crisis of profitability and in the aftermath of financial turmoil, is Pax Americana waning to such an extent that it is now being replaced by a new order of polycentrism? If this is the case has globalisation peaked, or is it simply morphing into some other form?

Globalisation reborn

The shift to Pax Americana implies a hegemonic dominance of the US over world affairs acting both as economic superpower and “world policeman”. Indeed, the view that globalisation is a primary product and objective of a singular state power has pervaded much of the literature on our period of post-war “peak” globalisation. The Marxist writers Leo Panitch and Sam Gindin, for example, appear to reduce the explanation for “peak globalisation” to American hegemony and its ability to “disarticulate” domestic capital in other nation states which, as a result, are “no longer represented by a coherent and independent national bourgeoisie”.32 However, as Alex Callinicos has shown in this journal, this position is in many respects an overstatement of the importance of the US’s ability and willingness to direct its economic and military power in the post-war era.33 In reality, the development of globalisation in the post-war period has been a much more complex affair, involving different stages and backgrounded not so much by an overwhelming US hegemony, but rather by a set of strategic position games of which the US has played the major, but not all-consuming, role.

We can discern a first phase, often defined as the “Golden Age” of western capitalism leading up to the economic crisis of the 1970s. This was the period of post-war reconstruction, marked by state intervention translated as social democracy and Keynesianism in Western Europe, the New Deal in the US and state capitalism in the east and parts of the developing world. The economic crises of the 1970s ushered in a more “leaden age” of slower growth punctuated by oil crises (and related wars) and the collapse of the Soviet bloc. By 1995 “peak” globalisation appeared to have been reached. Global trade integration reached its apogee and FDI began to surge forward. The 2008 financial crisis appears to mark a third stage of relative retreat within which the debate over the “end of globalisation” can be located.

As we have already noted a significant feature of post-war globalisation generally is that there has been an expansion of industrialisation in new regions of the globe. This marks a different pattern from our earlier period of “colonial” globalisation. The expansion has been encouraged by sources of cheap labour costs in the Global South and elsewhere which have been utilised for manufacturing production. The process has been uneven, marked by such developments as the industrialisation of China and “enterprise zones” such as the maquiladoras on the Mexican/US border, alongside longer-term processes of partial deindustrialisation in sub-Saharan Africa.34 By 2005, as Guillermo de la Dehesa records: “60 percent of Northern exports to the South are manufactures, as are 60 percent of Southern exports to the North (author’s emphasis). In general, the manufactures exported by the North are capital and technology intensive, while those exported by the South are labour intensive”.35 The industrial expansion has produced a degree of multi-polarity that has made “policing” the world system of nations more difficult.

The stages of development of post-war globalisation also need to be analysed in a little more detail to reinforce our assessment of the limits of US hegemony. To do this it is useful to assess the history of both US intervention and the international financial institutions (IFIs) as agents of dominance. The process of restructuring the world economy began as the Allies sensed victory towards the end of the war. The Bretton Woods Agreement was signed in 1944. The participants at the three-week long meeting in a New Hampshire hotel included representatives of all 44 of the Allied Powers including the USSR and the emergent new state of Yugoslavia. New supranational institutions, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, were created after the meeting to stabilise the world financial system, essentially by fixing exchange rates to the dollar (which in turn was fixed to gold). Money would be transferred through the institutions from those states with surplus funds (creditors) to those in deficit (debtors) to preserve the stability of exchange rates and to help boost world trade. Loans would be repaid with interest determined by the IMF/World Bank. US leadership was assured. Both institutions were to be based in the US, where two thirds of the world’s gold was held, with governing and decision-making bodies dominated by creditors. The final agreement was not ratified by the USSR, which claimed that the institutions were “branches of Wall Street”.36

The political effect of Bretton Woods was to tie the Western powers into a shared economic project of financial and economic reconstruction, albeit under US leadership. To a large extent it marked a departure from earlier periods of imperialism under the British and others in that the US sought to consolidate its power and influence through economic pressure rather than through a more brutal territorial expansion. This new strategy stood in contrast to the failures of the inter-war years, which had seen a retreat into economic nationalism, and then depression and reinvigoration of the drumbeat of war. A secondary development was the creation in 1947 of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), designed to complete multilateral agreements on tariff reductions, to regulate tariffs and boost world trade. GATT morphed into the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in 1995 and the last round of deals under the process of liberalisation was struck as part of the Doha Round in 2001. Doha marked a notable shift in WTO objectives, in that there was a specific focus on the agriculture and service sectors outside of manufacturing.37

On the geopolitical front the Korean War heralded the consolidation of the Cold War, by justifying high levels of military spending and committing the US to maintaining a military presence in Western Europe. The US buttressed its European allies through Marshall Aid in 1948, which amounted to a total of $17 billion granted in aid in return for purchase of US commodities such as food, fertilisers, machinery and fuel. The plan also had an ideological edge, advancing the cause of institutions that allowed labour representation to promote a social democrat alternative to Western Europe’s still large Communist Parties.38 While the Soviet Union and its satellites were offered Marshall Aid, the offers were blocked by Stalin, who in turn developed an alternative “Molotov Plan” in Moscow’s own sphere of influence. Similar programmes were established by the US for Asian countries fulfilling the “Truman Doctrine” of 1947 which detailed a US mission to create a physical barrier to the territorial spread of “Communism”. A need for finances to reinforce the doctrine was engendered by the UK’s post-war admission that it could no longer fund the suppression of the Communists in the borderland region between East and West that was Greece. The net effect of these US-led political and economic initiatives was that a new era of military power was established both in the North Atlantic (the Washington Treaty establishing NATO was signed in 1949), and in the Pacific.

The borders of this new globalised world were drawn in Cold War terms, relatively fixed in Europe, but less specific in the Far East (until after the Vietnam War), and more fluid in Africa and South and Central America. By accepting US “leadership”, smaller nation states could be guaranteed a share, however small, in an advancing world economy within what Giovanni Arrighi has described as a distinct “regime of accumulation on a world scale” associated with a particular hegemonic state (ie the US).39 This new regime provided the necessary political stability and ushered in a “Golden Age” of Western capitalism in the immediate post-war years as the economy expanded alongside rising real incomes and the mass purchase and production of consumer goods. Behind the golden age, however, were materials of a darker hue—coal and oil. Fossil fuels steamed ahead to shape a world economy in which the mass production of the motor car allowed for further expansion of the cities into the suburbs leading to what Ian Angus has called the “great acceleration” in carbon emissions.40 It frameworked the political economy of US and other smaller imperialisms in chasing oil and subjugating oil-rich states to their will.

While the new “regime of accumulation on a world scale” was successful in many of its aims (at least from the perspective of the American ruling class) it was not without its problems. Neither US nor indeed Soviet “hegemony” was accepted automatically by nation states in the less developed world. Newly independent states (NIS) such as India and Pakistan and many African and Latin American states, as well as the Titoist regime in Yugoslavia were keen to distance themselves both politically and economically from the major powers. At an inter-state level the desire for independence from both Washington and Moscow took its effect in the establishment of the non-aligned movement following the Bandung Conference in Indonesia in 1955. The main movers of the Conference were the states of Indonesia, Pakistan, India, Burma and Ceylon (Sri Lanka). The People’s Republic of China was represented at the conference (just six years after the Mao revolution) fuelling US fears of an alternative source of Communist influence.

US post-war foreign policy had sought to court anti-colonial elements in the Global South, but this brushed against a parallel objective of drawing closer to those very countries (France, Britain, Spain, etc.) who had been culprits in colonial misdeeds. This presented US hegemonic intentions with a dilemma, so too did the “human rights” approach of Bandung when framed against the racist Jim Crow laws in the south of the US. The dilemma was partly solved by a change in the policy of the majority of the European colonial powers towards their colonies. Rebellion from below had first been met with repression, shootings and concentration camps, just like in the old days. But this strategy gave way in the face of continued resistance to one whereby local elites were cultivated to rule their countries, but within the continued remit of the interests of the former colonial masters. In the British case, as Chris Harman records:

Even where Britain did try to stand firm against making concessions to the “natives”—as in Kenya, where it bombed villages and herded people into concentration camps where many died, and in Cyprus, where troops used torture—it ended up negotiating a “peaceful” transfer of power to political leaders (Jomo Kenyatta and Archbishop Makarios) whom it had previously imprisoned or exiled.41

In political terms US hegemony survived the strains of the break-up of the colonies albeit by seeking accommodation with the elites of the newly independent states. The Soviet response was to parallel that of the West, by constructing its own trading bloc (Comecon) and by courting willing leaders of states not engaged by the West.42 Flare-ups were inevitable, most notably in the Berlin Blockade of 1948-9 and the Cuban missile crisis in 1962, but the Cold War remained cold. Western capitalism was allowed to expand across the majority of the globe unhindered and policed by growing US imperialism which sought to glue together the pillars of political, economic and territorial power.

But the “independence” of the NIS posed another problem for the US rulers’ intentions to expand global capitalism under its influence. Efforts were made by many of the NIS to develop their own economies through programmes of import substitution industrialisation (ISI), whereby state-promoted home-grown manufacturing would make up for the deficiencies in domestic industry that had accumulated under centuries of colonialism. Import substitution would act to encourage “nation building” by making the countries less dependent on the outside world. But it could only be achieved if tariffs on imports were raised and not lowered as required by the Bretton Woods/Washington mantra, and if tight exchange controls were imposed outside of the US dollar zone. The ISI approach was particularly popular in South and Central America, most notably in Mexico and Brazil and in Argentina under the 1950s Peronist regime. Currency exchange rates against the dollar and sterling were kept deliberately low to encourage exports and to make imports more expensive, while manufacturing was subsidised or nationalised through the state. Such a “state capitalist” approach was adopted by third world regimes where “young Turks” had assumed power by rebellion against the old order, such as Egypt, Libya and Cuba.

The development of a local auto industry was a key feature of the ISI programmes, partly because of the developing demand for vehicles in the age of oil, and partly because of a sense that an emerging nation state should have its own car brand (alongside a state airline and state railway). In India, for example, the old UK manufactured Morris Oxford was relaunched in 1957 and built within the country as the Morris Ambassador. For the following 30 years it was viewed as the “Indian” car. Some success can be claimed for ISI policies, as the growth rates of those countries pursuing it may testify. One study highlights that:

By the early 1960s, domestic industry supplied 95 percent of Mexico’s and 98 percent of Brazil’s consumer goods. Between 1950 and 1980, Latin America’s industrial output went up six times, keeping well ahead of population growth. Infant mortality fell from 107 per 1,000 live births in 1960 to 69 per 1,000 in 1980, [and] life expectancy rose from 52 to 64 years. In the mid-1950s, Latin America’s economies were growing faster than those of the industrialised West.43

ISI was grounded in critical trade theory, taking its cue from debates over “dependency” as it related to a post-colonial world. The associated Prebisch-Singer thesis, developed in 1949 by Argentinian economist Raúl Prebisch and Hans Singer (a UN economist), suggested that countries such as the UK went through an early stage of ISI as part of their own development.44 Indeed, ISI is presumed to work better in a developmental stage as the income elasticity of demand for manufactured goods is greater than that for primary goods such as food. This would mean that as incomes rise, while the demand for food stays roughly the same (assuming no one is starving), the demand for consumer manufactured products rises at a faster rate. If such manufactured goods are produced within the nation state, then a positive cycle of growth ensues. Without ISI, it is suggested, structural inequality would develop between the richer nations and the poorer, or the “core” and the “periphery”. This view has been put forward by dependency theorists as well as neo-Marxists such as Immanuel Wallerstein in his presentation of world systems theory.45 While this model seems to have had some success, it remains limited by its own contradictions, which are discussed later in this article.

By the 1970s the new rulers of the world, crystallised in the alumni of Harvard Business School and the Washington/Treasury nexus, had begun to challenge ISI in a global push for market liberalisation known more colloquially as neoliberal capitalism. However, it was not just the challenge of ISI that produced neoliberal mantras. More importantly, the economies of the advanced industrial nations entered their first crisis during the early part of the decade as growth rates faltered, debts accrued and inflation soared. Prior to 1973 the expansion of the system was almost unprecedented. As Michael Kidron observed in 1970: “High employment, fast economic growth and stability are now considered normal in western capitalism”, while the system as a whole had been working “twice as fast between 1950 and 1964 as between 1913 and 1950”.46 The underlying reasons for the onset of the economic reversal from “golden” to “leaden” age have been well rehearsed by authors familiar to this journal over decades.47 Evidence of a decline in the rate of profits from investment in western corporations from the late 1960s conjoined with the faltering of the “permanent arms economy” as the West German and Japanese growth spurt tailed off and US spending on arms became an increasing burden.48 The consequences of the slowdown alerted the ruling classes of western nations to the fact that a new way would have to be found to restore profitability, and the forces of the market were to be utilised as a result.

Enter the market, enter the dragon

We can date the beginning of the new wave of economic globalisation from the late 1960s onwards. The process was driven by a desire of the Western-based financial and industrial elites, increasingly stifled by saturated markets and declining profits on investment, to create new areas for production. This could restore profitability by reducing unit labour costs for certain types of batch and low technology production. The low-tech and assembly-based nature of production was to be facilitated by tapping into huge new reserves of labour in the Global South, drawn often from the peasantry or the urban dispossessed as well as child labour, at skill and wage levels which would be low enough to overcome increased transport to western markets and other infrastructure costs.

In Marxist terms it would then be possible for capital to undercut the socially necessary labour time required for many manufactured items previously made in the advanced industrial nations. A spin-off from the process would be to create new markets in the rapidly urbanising South for manufactured goods produced by Western multinational enterprises. An expansion in information technology capability engendered by the silicon chip (from the late 1960s) allowed for a leap forward in logistics capabilities, as did the construction of ships suited to the use of modular containerisation (the first dedicated container ship left Newark, New Jersey, in 1956).

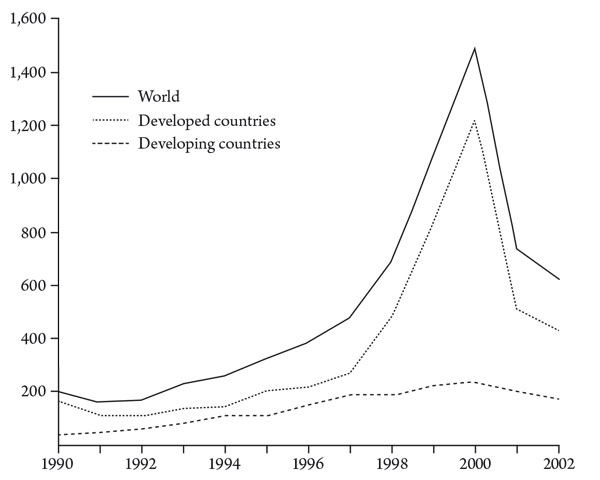

The resultant upturn in levels of FDI in the three decades after 1970, and the expansion of the volume of world trade over and beyond that of world production of goods and services that we have alluded to earlier in this article, then gathered pace. Growth in FDI was particularly strong in the late 1990s, including new cash flows into the post-Communist “transition” countries, before falling back in striking fashion after the 2008 crash. Much of the immediate pre-crash growth took place in the primary sector (agriculture and mining) and services, reinforcing the process encouraged by the WTO.49

Figure 1: World Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) trends (inflows in $ billions)

Source: UNCTAD, 2002, in Gallagher and Zarsky, 2006

However, this seeming juggernaut had to be accompanied by a process of bullying and coercion of the NIS within the Global South to open up the necessary markets to Western capital. Strategies of ISI would need to be abandoned, import tariffs reduced or abolished, exchange rate controls dismantled, and the state subsidisation of domestic industry end if the “market” was to rule supreme. This became the new neoliberal stage of capital accumulation strategy. As part of this strategy the institutions of Bretton Woods, the World Bank and IMF, began to work with local interlocutors in the process of coerced globalisation, by bribing and cajoling the political elites in the NIS to accept the pensée unique (single thought) of neoliberalism in return for a taste of honey in the new globalised economy. As Ngaire Woods has written in her book The Globalizers:

The [new] mission of the IMF and World Bank is not just to define economic programmes… Each institution deploys a mixture of technical advice and coercive power in bargaining with borrowing governments, lending or withholding resources, disbursing or suspending payments, and imposing various forms of conditions. Yet the institutions can successfully deploy this power only where they find and work with sympathetic interlocutors who are both willing and able to embrace the policies preferred by the institutions.50

This was sometimes a violent process, drawing parallels with our earlier period of globalisation. The first two Indochina wars had led to defeat for French and US imperialism leaving Indonesia as a key state from which Western imperialism could construct a defensive reaction. In the ensuing period Indonesia under General Suharto was courted and touted as the World Bank’s “model pupil”, but a million died in a purge against communists in 1965 as the regime imposed its will to allow full access for Western capital. The radical journalist John Pilger outlines in his book The New Rulers of the World that “within a year of the bloodbath, Indonesia’s economy was effectively redesigned in America, giving the West access to vast mineral wealth, markets and cheap labour—what President Nixon called the greatest prize in Asia”.51 With the collapse of the Soviet Union and Comecon in 1991, the forces of global market dominance were boosted once more. The state capitalist model had become increasingly entrapped by its own contradictions. State subsidies had isolated domestic industry from the full rigour of competition with Western capital. Increased trade between the Communist bloc and the West during the 1980s had only served to expose the differences and by the late 1980s sections of the nomenklatura, most notably with Mikhail Gorbachev’s programme of perestroika (restructuring), had grasped this and begun to look for ways to escape from a state capitalist to a full market model.

The following period of “peak” globalisation was thus backgrounded by a seeming victory of market capitalism over the state capitalism of the Eastern bloc. This all took place under the presidency in the US of Ronald Reagan, who together with Margaret Thatcher placed an immutable seal of approval on the mantra of capital accumulation over that of state direction, consolidating the ideological aspects of neoliberalism in the process. Indeed, the unrestrained entry of the market carried with it a re-regulation of pre-existing social settlements, especially in the field of labour protection and state benefits for the old or unemployed, whose social support structures were stripped to their bone on the basis that they were obstacles to free trade and unfettered competition.52 This is not to say that the “state” was abandoned by political and financial elites as an agent of capital accumulation. As Alex Callinicos reminds us, “Reagan’s combination of cutting taxes and boosting military spending hugely increased government borrowing, representing, according to Robert Brenner, ‘the greatest experiment in Keynesianism in the history of the world’”.53 Rather, the state was used as an agency to re-regulate the system in the interests of a new regime of capital accumulation.

But did these new trends represent a monocentric or polycentric distribution of power? The new era of globalisation came with its complexities. While the motor was the spread of Western capital across boundaries, including a leap forward in the number of cross-border mergers and acquisitions, there remained a need for state support. As Chris Harman wrote in this journal in 1991:

Capitalism needs states—to maintain the local monopolies of armed forces that prevent some capitals using direct, Mafia style violence against others, to impose regulations that prevent some capitalists defrauding others, to organise labour markets and to prevent recession turning into economic collapse. The greater the threat of crisis, the greater the need for the state. And yet the international scale of capitalist operations means they continually escape from any possibility of control by states.54

One way of attempting to ensure such security across state boundaries was the creation of economic blocs on a geopolitical basis, such as that of the European Economic Community/EU. NAFTA under US leadership, ASEAN and so on. Most certainly the leading player was and continues to be the US, but the first signs of an alternative axis of power began to appear with the consolidation of the EEC/EU across the Atlantic in the 1970s and then with the rise of Japan in the 1980s. Indeed, Japan’s rise as an industrial powerhouse and an alternative locus of power in the Pacific with its new manufacturing methods prompted a state initiative in the US to study Japanese work organisation and to launch the “lean production” model across Western enterprise.

The resultant book in 1990 by James Womack and colleagues, The Machine That Changed the World, became the new mantra of business school education not only in the US but across most of the West, challenging traditional Taylorist methods with new forms of team-working, continuous improvement and lean production.55 Japan’s new prominence in industrial manufacturing also prompted shifts in global supply chains as the lean production model combined with global economic trade networking in an effort to create value-added on a worldwide “just in time” basis. Auto manufacture, for example, was spread across many countries in the supply chain, and at the final “screwdriver” factory, auto parts from a dozen or more countries were added to the chassis.

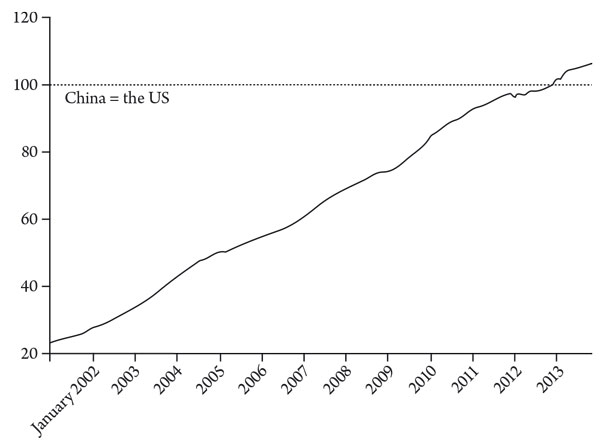

But in more recent years it has been the rise of China that has worried American strategists even more and created further possibilities for polycentrism. The US’s position as leader in world trade in merchandise was eclipsed by China in 2012, following years of Chinese economic expansion. According to the WTO, China’s share of world export trade by 2014 was 12.4 percent, followed by the US at 8.6 percent and Germany at 8 percent. The UK (at 2.4 percent) was the ninth largest trader.56 Interestingly, the total share of the EU’s major exporting countries was well over 20 percent, making the EU in aggregate the major player in world trade. At the time of China’s entry into the WTO in 2001 its share of world trade was only one fifth that of the US, so the growth has been spectacular and, of course, accompanied by suspicions of Chinese military ambitions in the Pacific. Since 2000 the growth of China within the world economy has been paralleled by a shrinkage in the importance of the US. US imports have fallen from 17 percent of the world total to 12 percent over this recent period, while its percentage share of exports has fallen from 12 percent to 8 percent.57

Figure 2: Chinese merchandise trade as percentage of US

Source: Thomson Reuters datastream

The relative collapse of US trade hegemony—mainly at the hands of China, but to a lesser extent the EU under the powerhouse of Germany—has been accompanied by a rapid increase in Chinese investment overseas, including grants and loans to less developed states made without the stringent neoliberal strings that come attached to similar cash sums from the IMF or World Bank. The majority of Chinese FDI is geared towards natural resource extraction activities in Africa, Australia, Canada and Latin America. But as part of Beijing’s “Going Global” strategy, investment in high tech industries is increasing as the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) seeks to drive the economy to a higher end of the world’s markets in manufacturing production. In Australia, a major recipient of Chinese investment, for example, FDI has in the past been focused on mining. But more recent investment has shifted towards healthcare and agribusiness.58

The threat of commodity monopolisation from China is perhaps of greater concern to the US elites than China’s growing domestic economy. As fossil fuels are challenged by potential climate change regulation, and rare earth metals are purloined by China, then the US business model, historically based on cheap oil and coal, becomes threatened. Peak globalisation corresponded with a period of peak oil and, as James Howard Kunstler has argued in The Long Emergency, as the peak has passed, countries heavily dependent on cheap oil, such as the US with its car-oriented cities and long inter-state transportation distances, may be “sleepwalking into the future”.59 Trump’s appeal for “Pittsburgh not Paris” over an international climate agreement is a real sign of the times.

Chinese multinationals may also become larger players in hoovering up privatised public services at the expense of the US. So a second sign of the times is the threatened post-Brexit trade deal between the US and the UK which may well involve granting US multinationals access to Britain’s health service.60 Indeed, the British state enters its Brexit negotiations at a time of increasing uncertainty over the future of existing tariff regimes among old and newly emerging power blocs. Britain is very much a “middle power” within the world of trade agreements and new country by country agreements.61 Negotiating a way through such uncertainty will clearly expose tensions among financial and political elites not just in Britain and the EU but across a wider range of potential trade partners. For the left, however, as Guardian journalist Larry Elliott reminds us, opportunities arise with Brexit to create an argument for retreat from the mantras of the free market. Brexit, he argues could “provide for public ownership, lower rates of VAT to help those on the lowest incomes, state aid to support sunrise industries, and fair trade agreements with developing countries”.62

What next?

We are undoubtedly witnessing a reordering of the locus of power within the world economy, as US hegemony is challenged and visions of a more polycentric world continue to proliferate. Trump and “Trumpism”, broadly defined as a nationalist form of populism focused on economic protectionism and more restricted immigration, appears as a reaction from the right dressed up to appeal to disaffected workers isolated from the alleged benefits of a globalised economy. Such alleged benefits were sold to workers on both sides of the Atlantic by Democrats from Clinton to Obama to Clinton and their Blairite equivalents in “social democratic” Europe as an antidote to economic uncertainty. The consequent “social liberalism” meant lower real wages, increased inequality and savage attacks on public services as market forces were let loose. However, it is not the end of globalisation that we are witnessing, but rather a reshaping which involves a fragmentation of existing trade relationships as new ones are formed in a new world regime of capital accumulation. Britain’s Brexit and post-Brexit negotiations for new trade deals are part of this process, with new deals proposed not just with the US but with China and India as well as the rest of the EU. However, the whiff of economic nationalism and protectionism remains in the air, driven still by electoral ambitions to appeal to a working class pacified by anti-import and “nothing can be done about globalisation” rhetoric from trade union leaders and others.

But, far from such economic nationalism being a new idea, it has in fact a deeper and longer history within the Republican Party and with Trump himself. Trump’s critique of US trade policy goes as far back as the 1980s, in response to the “threat” from Japan as the new pacemaker in automobile and consumer goods manufacture.63 As Adam Tooze suggests, Trump has since successfully convinced a large enough section of the Republican Party of his views to make economic nationalism and protectionism live issues.64 Such a redefining of the US “business model” is possible within the confines of a global political economy. Indeed, in real terms a shift towards a more protectionist world would harm the US economy a lot less than those of its rivals. In the US economy trade (imports and exports) measured about 30 percent of all GDP in 2014. This is compared to shares of 59 percent in the UK, 42 percent in China, 85 percent in Germany and up to 167 percent in smaller industrialised countries such as Belgium.65 This makes any protectionist turn less harmful to the US in aggregate than to its competitors, giving Washington continued asymmetrical bargaining power in negotiations over trade deals. This economic power will continue to be used by the US, most likely with the objective of restricting the lineage of global supply chains by shifting a higher proportion of production towards home based manufacture. However, the strategy is a huge gamble, particularly as China waits in the wings ready to scoop up the remnants of a new US economic isolationism.

Such a strategy, if continually pursued by Trump, would also necessarily involve a parallel redefining of inter-state relations, most notably with China and to a lesser extent with the emergent power ambitions of the Gulf States. The internecine wars within the Trump administration, especially with his reliance on the military within his cabinet, are testament to the tensions that will no doubt ensue. The EU, under the motor of Germany, also remains a major player within world trade, and its political elites will seek to resist pressures for isolationism and protectionism as a result. The future of globalisation is thus a contingent one dependent on the outcomes of such tensions both on a world scale and also within the US political and financial elite. Let us not also forget that after four decades of an increasingly globalised economy the world is more unequal in terms of wealth distribution than at any time since the early part of the 20th century. When coupled with a decade of austerity since the financial crash, neoliberal capitalism has awarded its working class with a steady succession of accumulated grievances in the core industrial countries. This is a heady cocktail, the outcome of which is unpredictable.

Martin Upchurch is Professor of International Employment Relations at Middlesex University, London, UK.

Notes

1 Donnan and Sevastopulo, 2017.

2 Wolf, 2017a.

3 Donnan, 2017.

4 Although the mayor of Pittsburgh was very critical of Trump—Watkins, 2017.

5 Fukuyama, 1989.

6 Ferguson, 2005.

7 Saul, 2005.

8 Hirst and Thompson, 1999.

9 Meadway, 2015.

10 Streeck, 2017.

11 See Maddison, 1991 for data.

12 World production figures since 1950 can be unreliable, due to vagaries in data collection, but estimates of proxy growth in PPP (purchasing power parity) from 1950 collated by the Institute of Institutional Economics suggest that world growth rates were approximately 2.5 percent annually from 1950 to 1980 and 2.65 percent from 1980 to 2000 (see https://piie.com/publications/chapters_preview/348/2iie3489.pdf).

13 Wolf, 2017b.

16 See figure 6 in Wolf, 2017b.

17 Davis and Hilsenrath, 2017.

18 UNCTAD, 2012, p15.

19 Foroohar, 2016. Ironically American Apparel has declared bankruptcy and has since been bought by a Canadian company.

20 OECD, 2017a.

21 OECD, 2017b.

22 Marx, 1867, p918.

23 See Cox, 2004 for a review of debates on the relationship between capitalism and imperialism.

24 Engels, 1844, p1.

25 Newsinger, 2006, p48.

26 Davis, 2001, p311.

27 Bairoch, 1982, pp269-325.

28 Hobsbawm, 1995, p51.

29 Hobsbawm, 1995, p51.

30 Hobsbawm, 1995, p51.

31 Pollard, 1985, p492.

32 Panitch and Gindin, 2003, p47.

33 Callinicos, 2005, p117.

34 Approximately 3,000 factories (maquiladoras) employing over one million workers are ranged along the border inside Mexico, primarily servicing the US market within the structure of NAFTA. For a review of the evidence of “de-industrialisation” in sub-Saharan Africa see Grabowski, 2015, p51.

35 De la Dehesa, 2006, p31.

36 Mason and Asher, 1973, p29.

38 See Carew, 1987.

39 Arrighi, 1994, p9.

40 Angus, 2016.

41 Harman, 1999, p557.

42 Comecon’s original members were the Soviet Union, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland and Romania. Albania was a member from 1949 until the end of 1961. The German Democratic Republic joined in 1950 and the Mongolian People’s Republic in June 1962. In 1964 Yugoslavia became a trading associate. Cuba, in 1972, became the 9th full member and Vietnam, in 1978, became the 10th.

43 Hoogvelt, 1997.

44 See Toye and Toye, 2003, pp437-467 for a detailed explanation of the Prebisch-Singer hypothesis.

45 Wallerstein, 1974.

46 Kidron, 1970, p11.

47 See, for example, Harman, 2009.

48 For a review of the permanent arms economy debate, see Pozo, 2010 in this journal. For an ongoing assessment of the data on the fall in the rate of profit in the post war period, see Roberts, 2016.

49 UNCTAD, 2010, p6.

50 Woods, 2006, p10.

51 Pilger, 2002. See also the video at http://johnpilger.com/videos/the-new-rulers-of-the-world

52 Upchurch, 2009.

53 Callinicos, 2017, citing Brenner, 1998, p182.

54 Harman, 1991, p45.

55 Womack and others, 1990.

57 Romei, 2014.

58 KPMG and The University of Sydney, 2016.

59 Kunstler, 2005, p1.

60 See Watts, 2017.

61 See Trommer, 2017 for an up to date assessment.

62 Elliot, 2017.

63 Clark, 2015.

64 See his blog—Tooze, 2017.

65 Ortiz-Ospina and Roser, 2016.

References