In autumn 1979, Tony Cliff, writing in International Socialism, surveyed the landscape of labour struggle in Britain. He concluded that, in the second half of the 1970s, the balance of forces had tilted in favour of the ruling class.1 A remarkable series of battles in the early 1970s had marked the high-water mark of post-war class struggle. Now Cliff’s article heralded a debate that culminated in the acceptance within the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) of what became known as the “downturn” thesis.

The downturn was a result of multiple factors. Social democracy showed its capacity to absorb workers’ militancy and redirect it into safe channels, both through the Labour Party, in power from 1974, and the “left” union leaders who had come to prominence.2 They were aided by the Communist Party, whose own militants were increasingly directed to work with left-wing union officials, rather than focusing on rank and file activism. Alongside this, there were efforts to draw senior union stewards and convenors into managerial structures and away from shop-floor militancy. Finally, there was increasing demoralisation due to economic crisis and a weakening of solidarity, reflected in a growing tendency of workers to cross one another’s picket lines. The period from 1979 intensified this shift; the offensive by employers sharpened, and a neoliberal policy regime was consolidated under the newly elected prime minister, Margaret Thatcher. Defeat for the 1984-5 miners’ strike ruled out any reversal in the fortune of workers for many years to come.3

Why does this history matter? Because, after many false dawns, there are signs of a revival of industrial militancy today. The following analysis will offer a necessarily provisional account of this revival.

A new situation

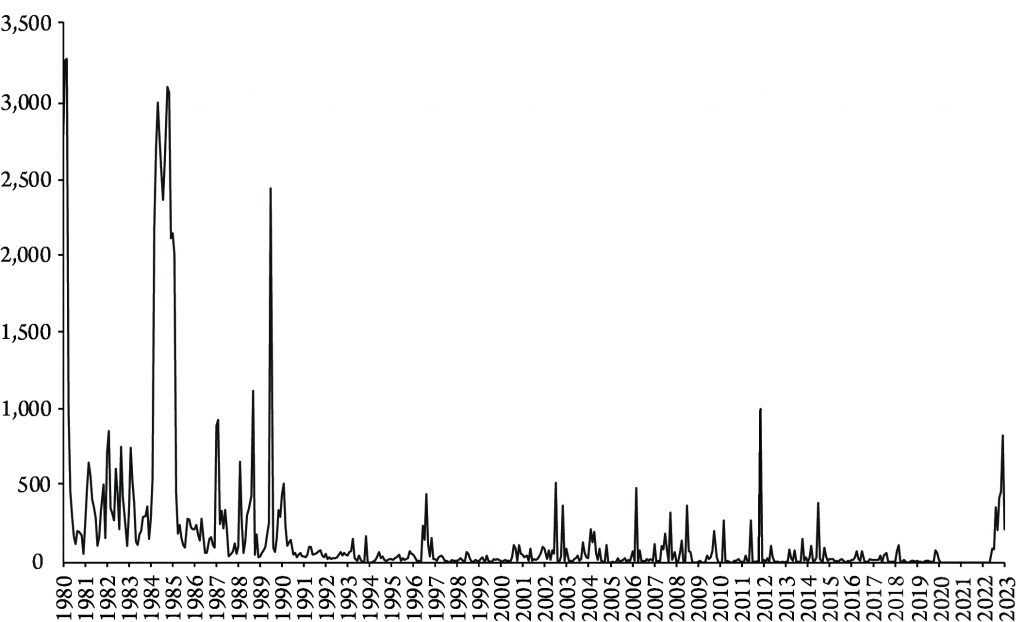

Figure 1 shows official monthly strike figures.4 The current uptick is a break with much of the past three decades. On just one occasion in this period, November 2011, has the monthly strike figure exceeded that of December 2022. However, the huge public sector strike over pensions in November 2011 lasted just a single day before the action was brought to a halt by union leaders. In contrast, by January this year, the total strike days for the preceding six months had hit 2.5 million, a figure last seen in 1989. We are witnessing a much more sustained pattern of action than earlier upticks.

Figure 1: Monthly working days “lost” (thousands) due to industrial action, January 1980 to January 2023

Source: ONS labour market statistics

What has produced this new situation? First, there are the long-term grievances of workers. In the post-war period up to 2007, except for a two-year blip during the inflationary crisis of 1976-77, workers’ “real compensation” rose every single year.5 The annual increase averaged 2.6 percent and real compensation was, on average, five times higher in 2007 than 1945. Since the economic crisis of 2008, that progress has halted. Average wages fell thereafter, recovering only a little bit in the run-up to the pandemic.6 Household income data tells the same story. If the 1977-2007 trend had continued, the average household would be 52 percent (around £20,000) better off.7

This income stagnation was followed by the pandemic itself, in which many workers made enormous sacrifices. Many of the groups who have taken strike action recently, such as health workers and bus drivers, suffered particularly harshly before being offered dismal pay awards, rather than being rewarded for their efforts.

As lockdown conditions eased, inflation took hold, further hammering wages. In the private sector, labour shortages meant that some groups were able partially to offset the decline in real wages, usually without industrial action. In the public sector, largely covered by annual collective agreements, the fall in wages was more pronounced. It is also in these areas that trade union membership has proved most resilient—around 13 percent of private sector workers are in a union, compared to 50 percent in the public sector.8 The uptick in strike activity has been focused on the public sector along with “private” organisations that retain national collective bargaining or operate in a framework created by the state (for example, Royal Mail, the rail network and the universities).

The wave of action began in June 2022, with strikes by the RMT rail union at 13 different train companies (increasing to 14 from July) as well as Network Rail and the London Underground. The RMT strikes were later joined by action from two other rail unions, ASLEF and TSSA. The Communication Workers Union also began strikes in Royal Mail and BT Openreach that month. By autumn, higher education staff in the University and College Union (UCU) had begun their action, as did the main Scottish teaching union, the Educational Institute of Scotland (EIS). Civil service workers in the Public and Commercial Services Union (PCS) struck from December 2022. Then, at the end of 2022, the Royal College of Nurses (RCN) held the first national strike action in its 106-year history, along with ambulance workers in the GMB, Unison and Unite across several NHS trusts. In January, the National Education Union (NEU) announced that it had won a strike ballot for action in schools in England and Wales; junior doctors in the British Medical Association (BMA) in England did the same in February. By this point, over a million workers had a mandate for strikes. Reflecting the strength of feeling among workers, each of these ballots overcame the onerous legal restrictions introduced in 2016, which only allow industrial action if a turnout of over 50 percent is achieved.

The problem of bureaucracy

In earlier periods, particularly those associated with the most impressive gains by workers, struggle often took place outside the framework of official union action. As Cliff writes:

Between the two wars and after the Second World War, the major unions were headed by right-wing leaders… However, the fact that they collaborated with employers and the state did not bring them into actual conflict with the rank and file in the majority of cases… Usually, management retreated under the duress of a short-lived strike, that is, before the trade union bureaucracy managed to intervene and discipline the workers… In many cases, a central element in the tactics of the militant was to win the strike before trade union headquarters heard about it.9

As well as indicating the historical importance of unofficial action, this passage also points to the key faultline within unions: that lying between rank and file members and the union bureaucracy.

Where there is sufficient stability to do so, unions tend to develop a bureaucracy standing outside the workplace.10 This consists of the trade union leaders and the unelected officials operating under them. The social function of this bureaucracy is to negotiate the terms under which union members are employed and exploited. This involves giving expression to the grievances of members but also channelling these into formal structures for bargaining and negotiation (or creating these structures if they do not already exist). Thus, the bureaucracy operates as a conservative force. Officials see “negotiation, compromise, and the reconciliation of capital and labour as the very stuff of trade unionism. Struggle appears as a disruption of the bargaining process—a nuisance and an inconvenience that might threaten the accumulated funds of the union”.11 Moreover, because they are based outside the workplace, trade union officials are not directly subjected to the pressure of managerial attacks or the counterpressure of rank and file anger. Whether workers win or lose their battles over redundancies, wages or conditions has little material impact on the bureaucracy itself—unless it ultimately reaches the point where the viability of the union itself, and hence its paid officials, is threatened.

This analysis holds whether specific members of the union bureaucracy are drawn from the right or the left. Those differences do have some relevance. The election of left-wing union leaders, such as Unite’s Sharon Graham, who raises the prospect of greater union action, and the RMT’s Mick Lynch, who articulates basic class politics in media interviews, can increase the confidence of union members. Ultimately, though, the faultline between rank and file workers and the union bureaucracy is of greater significance. As the Cliff quote earlier suggests, in the inter-war and post-war periods, workers could make huge gains through independent rank and file action while under right-wing leaders. Yet, they suffered major defeats in the late 1970s and during the 1984-5 miners’ strike under much more left-wing leaders.

To say that the bureaucracy is a conservative force does not mean that unions consist of a seething mass of workers held back by a thin crust of officialdom. It does, however, mean that, when rank and file workers move into action, the tension with the union bureaucracy tends to grow. In this context, the bureaucracy often leans on the most passive union members. This is one reason why officials like electronic surveys or postal ballots of members, which give the same weight to members who scab as those who carry strike action through picketing. Conversely, rank and file militants often prefer votes on picket lines, at mass meetings and in strike committees.

In periods of sustained struggle, the tension between rank and file members and the bureaucracy can lead to the development of rank and file organisation. At its best, such organisation can place pressure on the union bureaucracy and act independently of it through unofficial action. In 1915, this was expressed well by the first leaflet issued by one such organisation, the Clyde Workers’ Committee:

We will support the officials just so long as they rightly represent the workers, but we will act independently immediately they misrepresent them. Being composed of delegates from every shop and untrammelled by obsolete rule of law, we claim to represent the true feelings of workers. We can act immediately according to the merits of the case and the desire of the rank and file.12

In the 1920s and during the three decades following the Second World War, when such organisations flourished, it made sense for revolutionary socialists to adopt a rank and file strategy. For the SWP and its forerunners, this meant orienting on networks of shop stewards who typically led the disputes of the 1960s and early 1970s.13 This involved seeking to overcome the fragmentation of workplace organisation by creating a national rank and file movement, in parallel with building revolutionary socialist organisation in workplaces. The SWP achieved some success in implementing such a strategy in the early 1970s, but the success was short-lived, ending with the downturn.14

The character of the action

To understand the character of the strikes today, it is necessary to explore the impact of the four-decade downturn on the labour movement.

The strength of the trade union bureaucracy is in inverse relation to working-class self-confidence. By weakening the impulse towards rank and file activity, defeats can be self-reinforcing. Strikes have tended to become highly orchestrated affairs, limited to official action within a considerably tightened legal framework. Indeed, legal formalities can further strengthen the grip of the bureaucrat, centring discussion on balloting procedures, codes of practice on picketing and so on.

Today, the number of workers who have direct experience—or even indirect recollections—of independent rank and file activity is negligible. A worker who was 20 at the time of the great labour struggles of 1972 would be in their 70s now. Many of the former strongholds of such activity have diminished weight within the working class. In his 1979 article, Cliff identified “shipyards, mining, docks and motor vehicle manufacturing” as key sites of class struggle in the 1960s and early 1970s.15 In the two decades from 1975, employment in manufacturing fell by over a third, mining and quarrying by more than two-thirds. Employment on the docks suffered a similar collapse. That does not render the workers remaining in these areas powerless—compact groups in these industries can have a major impact, as has been the case in recent dock strikes, which I discuss below. However, the areas of work that have grown most dramatically, particularly within the public sector and service industries, have not known strong traditions of rank and file organisation—and have not yet experienced sufficient struggle to develop them.16

There are some counterexamples. For instance, in the 1990s and early 2000s, a rash of struggles in Royal Mail was led by rank and file workers with cooperation from sections of the left of the union bureaucracy. However, this organisation was allowed to wither and, by the time a national dispute developed in 2007, the sympathetic left officials had been drawn into the upper echelons of the union machine. The strike ended in a weak compromise brokered by the bureaucracy.17 In addition, the analysis above does not preclude explosive unofficial action. A long decline of union membership, particularly in the private sector, and the weakening hold of the institutions of social democracy on the working class, mean that workers outside the mainstream union movement can suddenly erupt into activity. That was the case at Amazon, where unofficial “wildcat” strikes by workers in distribution hubs last autumn helped spur the development of union organisation.18 There are also occasions when relations between unions and employers become so cosy that workers resort to unofficial action—as happened on North Sea oil and gas rigs last year.19

However, by and large, the current strike wave takes the form of mass bureaucratic strikes, often over one day, occasionally a few more, and usually with large gaps in between. This episodic character allows employers to ride out the action and limits the extent to which rank and file members can take initiatives and develop their own capacity to organise.

For these reasons, union militants and organisations such as the SWP have argued to escalate the strikes. Some union leaders have accepted the argument for one kind of escalation: increasing coordination between unions. On two occasions, 1 February and 15 March, over half a million workers struck together, with large cross-union protests in many cities. This was certainly an advance on the sectionalism of the RCN, whose attitude seems to have been that the NHS is a “special case”, with widespread public sympathy allowing nurses to achieve a better pay deal than other workers.

Union leaders have been less receptive to the second, more important, form of escalation: moving to prolonged or even indefinite action. The threat of shutting down the railways, non-emergency services in the NHS, schools or the universities indefinitely, or at least for several weeks, would have tested the resolve of employers and the government far more sternly.

The effectiveness of such action is shown by some localised disputes that have made breakthroughs. In Liverpool, 580 striking dock workers in the Unite union won pay rises ranging from 14.3 to 18.5 percent in November, as well as seeing off the threat of compulsory redundancies. This came after workers rejected a 7 percent pay offer and took five weeks’ strike action in three blocks. In the same month, 250 bus drivers at Stagecoach in Hull, also in Unite, won pay rises of about 20 percent after four weeks of continuous action. At Arriva North West, bus drivers in the Unite and GMB unions announced indefinite action, which lasted for four weeks, rejecting an offer of 9.6 percent. Again, the basis was laid for an inflation-busting pay award, but this time Unite officials suspended the action, without consulting members. With strikes halted, workers ultimately accepted an 11.1 percent deal.

In one of the more surprising outbreaks of industrial action, around 2,000 criminal barristers in the Criminal Bar Association, who began taking strike action from June, escalated to all-out, indefinite action on 5 September. In early October, they voted to accept a deal that would increase their fees by 15 percent, far less than the 25 percent they had demanded to reverse a long-term decline in income. The 43 percent who voted to reject the deal were right to believe that more could have been won.

The bureaucracy reins in action

Instead of seeking to generalise from the best examples of escalation, the union bureaucracy has tried to keep strike action within strict limits and, increasingly, to negotiate deals to end it altogether. This does not preclude new groups joining the action. For example, hundreds of thousands of trade union members in local government were expected to ballot in spring. Nonetheless, by February and into March, a growing trend of retreats was becoming apparent.

Initially, the bureaucracy had limited room for manoeuvre. The government was eager to hold pay awards for 2023-4 below 5 percent and refuse to reopen 2022-3 pay awards (typically also around 5 percent).20 With the Retail Price Index measure of inflation over 10 percent from spring 2022, this amounted to a substantial pay cut. Yet, by early 2023, prime minister Rishi Sunak and chancellor Jeremy Hunt began to recognise the scale and breadth of the industrial action, which also enjoyed considerable public support, and that, in the union leaders, they had interlocutors eager to enter negotiations.

The precise degree of acquiescence varied. Pat Cullen, general secretary of the RCN, whose pay claim was for 19 percent, urged health secretary Steve Barclay to “get in a room and meet me halfway”.21 By mid-March, health unions, including Unison, the RCN and the GMB, were recommending a deal that would see a 2 percent one-off payment for 2022-3 (in addition to the 4 percent pay rise covering that year) and a 5 percent rise for 2023-4. In addition, they would receive a one-off 4 percent “Covid recovery bonus”. Although Unite did not recommend the deal, it did pause action while members voted on it.22 The proposals have sparked a cross-union campaign by rank and file NHS workers to reject the deal and resume strike action, indicating how elementary forms of grassroots organisation can be built in opposition to the bureaucracy.23

Junior doctors in the BMA held three days of strike action in hospitals in March. Once other health unions put an offer to members, there was pressure on BMA leaders to enter talks, and they duly wrote to Barclay on 17 March to begin this process. However, in this case, talks almost immediately broke down, leading the BMA to announce a four-day strike in April. In this case, junior doctors appear to feel confident due to their essential role in hospitals and the difficulty of replacing them, which means they may be able to force through a much higher pay award.

After 18 days of action in Royal Mail in 2022, the CWU agreed in January to meet employers for “intensive talks” and, in February, again called off strikes following a legal challenge. As Royal Mail sacked or suspended over 200 reps, and the CWU won a 96 percent vote for further action in a reballot, the union and employer issued a “joint statement” announcing yet more talks.24 At the time of writing, not a single day of strike action had been taken in 2023.

In BT, after nine days of action in 2022, CWU leaders recommended a deal to end the dispute, resulting in a £1,500 flat-rate pay increase from January to September 2023, on top of the £1,500 imposed in April last year. This amounts to a significant real-terms pay cut for most.

On the railways, the TSSA union had, by February, pushed through a deal to end its dispute, worth just 5 percent in 2022-3 and 4 percent in 2023-4. This offered no commitment on the closure of ticket offices, a key concern of rail workers. The RMT also suspended strike action set to take place in March in Network Rail, which employs signallers and track maintenance staff. Members voted to accept a deal similar to that obtained by TSSA but with slightly enhanced awards for those lower down the pay scale. Strikes were then called off in the ongoing disputes at specific rail companies, with officials claiming progress towards a deal.

After initially calling out just a limited number of sections in 2022, the PCS civil service workers’ union only called out its 100,000 members with a live ballot, across 124 government departments, on 1 February, three months into the dispute. After it successfully re-balloted departments such as Revenue and Customs, responsible for tax collection, an additional 33,000 joined the action on 15 March. At the time of writing, the PCS was in the unusual position of not having been offered a deal, but, as with other unions, the pace of escalation has been painfully slow.

In the school system, the leaders of the EIS, Scotland’s main teaching union, recommended a deal worth 7 percent in 2022-3 and 5 percent in 2023-4, with an additional 2 percent in January 2024. One EIS executive member noted, “It’s still far short of inflation and our 10 percent one-year claim. It’s not where we should have been, but the bureaucracy has shut it down. They didn’t want to keep going”.25 In England, the NEU brought its members out for four days in early 2023, which combined national and regional strikes, accompanied by large strike rallies. This helped the union recruit 50,000 new members. Kevin Courtney, one of the NEU’s joint general secretaries, initially bucked the trend among union leaders, arguing that ceasing strikes should not be a precondition for talks with the government. However, once the initial strikes ended, the NEU did enter talks, declaring a two-week “period of calm”.26 This followed the NEU executive calling off strikes in Wales in March, putting to members, without any recommendation, an offer of an additional 1.5 percent in 2022-3 (on top of the 5 percent already paid and a 1.5 percent non-consolidated element) and 5 percent in 2023-4.

While the other trade unions discussed here did at least strike, the Fire Brigades Union never got that far. In March, its members accepted a 7 percent deal for 2022-3, backdated from July, with 5 percent for 2023-4, as recommended by its executive.

These retreats have established a new norm: two-year deals, with a small, often backdated, uplift to the 2022-3 pay award and around 5 percent for 2023-24, adding up to a significant real-terms pay cut and far less than most trade unions had demanded.

One other dispute is worth considering in detail—that of academics and academic-related staff in the UCU union. As universities have increasingly been run along neoliberal, profit-seeking lines, UCU has repeatedly been forced to take industrial action. As a result, UCU branches have greater accumulated experience of industrial action in the past few years than any other union in Britain. Local branches, which average around 500 members, can have vibrant internal lives, and strikes have often been characterised by high levels of participation on picket lines. This has helped create embryonic networks of rank and file activists, sometimes linked to the UCU Left or UCU Solidarity Movement.27

The relative confidence of activists has allowed them to challenge two attempts by the union leadership to force through unpopular deals in recent years. The first, in 2018, came in the context of a series of strikes over the USS pension scheme, which covers older “pre-92” universities (established before university reforms in 1992). The then union general secretary, Sally Hunt, encouraged members to support a joint proposal between UCU and employers that would have suspended strikes and made significant concessions on the scheme. Adding insult to injury, the proposal encouraged members to reschedule disrupted classes from strike days. The result was an explosion of grassroots anger; the hashtag #nocapitulation began to trend on Twitter as hundreds of striking UCU members gathered outside the union headquarters while its executive met. This rebellion forced the union leadership to back down—something rarely seen during the long downturn in industrial action.

The current UCU strikes, involving both pre-92 and post-92 institutions, are led by Hunt’s successor, Jo Grady. She was elected in 2019, having come to prominence in the pension strikes and as an outspoken critic of Hunt’s leadership. Having won a mandate for action across the university sector in October 2022, Grady, along with other senior officers of the union, has repeatedly come into conflict with union activists. This has involved undermining elected bodies such as the union’s Higher Education Committee (HEC), composed of elected lay members and charged with running the dispute, on which the left has a significant presence. Electronic ballots of members with loaded questions and misleading communications through official union channels have become the norm.

Three episodes are particularly noteworthy. First, in January, Grady successfully mobilised pressure on the HEC to retreat from an earlier vote for indefinite action, using an e-ballot of members, the publication of an alternative industrial strategy and a branch delegates meeting.28 The left on the HEC managed to win a vote for 18 days of action over two months, but the opportunity to break the pattern of episodic action was lost. Second, in mid-February, the general secretary “paused” strikes, without any consultation with union bodies such as the HEC or the group of elected negotiators, announcing a “two-week period of calm” and retrospectively seeking support through an e-ballot.29

Third, in mid-March, Grady sought to suspend the final three days of scheduled strike action and consult members on a deal. The deal involved an offer of 5 percent for 2023-4 for most UCU members (rising to 8 percent for those nearer the bottom of the pay scale), some of which would be backdated to February 2023. Urged on by Grady, members had, a few weeks earlier, voted overwhelming in an e-ballot to reject this pay deal. Now, to sugar the pill, members were promised progress in reversing cuts to the USS scheme. Yet, this came without sufficient undertakings to guarantee the changes required—and would have no effect on staff at the majority of “post-92” universities outside the scheme. There were also some vague “terms of reference” proposed for future negotiations over issues such as casualisation, gender pay gaps and workloads. There was uproar among many of the activists carrying the strike action, which found expression on the HEC. The left prevented the deal being put to members and maintained the final three days of strikes.30

Some lessons

There remains a gulf separating the current situation from the high points of working-class self-activity of the past. It will take far higher and more sustained levels of activity to construct rank and file organisation, rebuild working-class confidence and lay the basis for a rank and file strategy for the revolutionary left.

Yet, official action can, as the example of the UCU shows, provide the terrain on which to create embryonic networks of rank and file activists. For instance, SWP members, along with other activists, have pushed for strike committees, composed of those mobilising and sustaining industrial action. As well as strengthening and building strikes, such committees can potentially coordinate activities between unions. In the UCU they might also provide a framework for an elected national strike committee, through which pressure could be brought to bear on officials to try to prevent efforts to shut down action.31 The push for strike committees was given greater impetus by the NEU’s Courtney, who also called for them to be set up locally among teachers. This official support suggests that the role of these bodies can be contested, with some viewing them primarily as a transmission belt for the bureaucracy rather than bodies with an independent role.

As demonstrated both by the UCU and efforts in the health unions to reject poor pay deals, creating embryonic rank and file initiatives cannot rely simply on promoting struggles as they rise. It must also involve challenging the bureaucracy when it blocks or limits action, even if this means revolutionaries starting out as part of a militant minority within their union branch or strike committees. Only a combination of argument and workers’ own experience of the bureaucracy will allow such a viewpoint to become the property of the majority.

This approach needs to be combined with developing revolutionary socialist politics in the working class, able to address the overall development of the struggle across the political and economic terrain. Leadership in the working class cannot be reduced to campaigning over “bread and butter” union issues. To take just one example, as the current economic crisis deepens, the government’s scapegoating of refugees crossing the channel will probably intensify. Combatting that—and challenging the far-right groups given confidence to attack hotels housing those arriving in Britain—is essential.

There are also valuable lessons to be taken from the international struggles of workers. The outburst of struggle in France shows many of the characteristics of the British experience but at a much higher level. President Emmanuel Macron’s decision to increase the pension age, long desired by the ruling class as part of embedding neoliberalism, has sparked a huge movement and created a political crisis. Twice in March, amid mass strikes, over 3 million joined demonstrations, according to unions. Though triggered by the pension assault—important in itself—the action has encompassed many other issues including pay, insecurity and, as it developed, some of the broader questions of how society is run that flowed from the Gilets Jaunes (yellow vest) movement that began in 2018.

The fury on the streets reached new levels after Macron used one of the most undemocratic clauses of the constitution, shaped by General de Gaulle in 1958, to force through the pension changes without a vote in parliament, fearing he did not command a parliamentary majority. Although he just about survived the subsequent vote of no confidence, the aftermath saw riots in many cities—met by high levels of police violence—and gathering strikes. These strikes have seen a much greater level of self-organisation at the base than in Britain, with serious efforts at coordination between sectors as well as workers taking matters partly out of the hands of union leaders. This has been necessary because the union bureaucracy, even when it speaks left, has also constrained and narrowed the struggle. Even at a much more elevated level of struggle, the same issues of leadership and rank and file control emerge.32

Even if the current wave of strikes in Britain ebbs due to the conservatism of the bureaucracy, we remain in a period in which new centres of workers resistance are emerging, haltingly, from the long downturn. Our task is to ensure that each subsequent wave of struggle begins from a higher point of departure than the one before. That means learning both how the workers’ movement can advance and how best we can resist its retreats.

Joseph Choonara is the editor of International Socialism. He is the author of A Reader’s Guide to Marx’s Capital (Bookmarks, 2017) and Unravelling Capitalism: A Guide to Marxist Political Economy (2nd edition: Bookmarks, 2017).

Notes

1 Cliff, 1979. Thanks to Iain Ferguson, Charlie Kimber, Sheila McGregor and Mark Thomas for comments on earlier drafts.

2 The “terrible twins”, Jack Jones and Hugh Scanlon, became, respectively, leaders of the Transport and General Workers Union and the Amalgamated Engineering Union in 1968.

3 Harman, 1985.

4 This data does not give a full picture of union activity. However, the paucity of unofficial action today at least makes it a relatively accurate measure of strikes.

5 “Real compensation” is wages plus other social contributions made by employers, adjusted for inflation.

6 See the Bank of England’s “A Millennium of Macroeconomic Data” database—www.bankofengland.co.uk/statistics/research-datasets

7 Romei, 2023.

8 Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy statistics for 2021.

9 Cliff, 1979, p35.

10 There are exceptions such as in Russia in the early 20th century, where a surge in union organisation came in the context of the 1905 Revolution and the formation of soviets, which combined economic and political demands. There was little space, under conditions of near illegality, for the formation of a stable, reformist bureaucracy in Russia prior to 1917—Cliff and Gluckstein, 1986, pp13-20.

11 Callinicos, 1982, p5.

12 Cited in Callinicos, 1982, p11.

13 Shop stewards would today be called “union reps” in many contexts.

14 Callinicos, 1982, pp30-36.

15 Cliff, 1979, p1.

16 Callinicos, 1982, p34.

17 See Kimber, 2009, pp46-48.

18 Squire, 2022.

19 Kimber, 2023a.

20 Parker and Wright, 2023.

21 Pickard, Georgiadis and Strauss, 2023.

22 It should also be noted that, where pay deals are “unfunded”, they will result in further cuts to health or education provision to pay for them.

23 Prasad, 2023.

24 Finnis, 2023.

25 Kimber, 2023b.

27 UCU Left, in which groups such as the SWP participate, organises a left slate in union elections and is oriented on rank and file activism. The UCU Solidarity Movement is a broader grouping seeking to coordinate struggles among branches.

28 Nominally, the HEC controls strike action in higher education.

29 Squire, 2023.

30 At the time of writing, UCU members were balloting to renew their mandate for action.

31 See the proposals at https://uculeft.org/he-disputes-in-jeopardy

32 See Kimber, 2023c, and subsequent articles in Socialist Worker, for a taste of these arguments.

References