For God’s sake, women, go out and play! Instead of staring round to see what wants polishing or rubbing, go out into the open and draw the breath of the moors or the hills into your lungs. Get some of the starshine and sunlight into your souls, and do not forget that you are something more than a dish washer—that you are more necessary to the human race than politicians—or anything. Remember you belong to the aristocracy of labour—the long pedigree of toil, and the birth right that nature gives to everyone has entitled you to an estate higher than that of princes.

“Our Right to Play”, The Woman Worker (14 April 1909).

In 1914, Ethel Carnie Holdsworth wrote that “literature up till now has been lop-sided, dealing with life only from the standpoint of one class”.1 She dedicated most of her life to redressing the exclusion of working-class and female voices from literature and to promoting the cause of socialism through her writing. 2Carnie was a Lancashire mill worker and author who is believed to be one of the first working-class women in Britain to publish a novel. In her heyday, she outsold H G Wells.3 No other working-class woman sustained a writing career for so long and explored such a variety of literary styles as Carnie.4 She was not only a best-selling novelist, but also a popular poet, a campaigning journalist and a revolutionary socialist.

Carnie was unique among women writers of the early 20th century because she combined literary success with both personal experience of the mills and overt political commitment. Throughout the 19th century, socially committed novelists like Charles Dickens and Elizabeth Gaskell had explored class conflicts, often presenting the reconciliation of the classes through personal friendship and marriage as the solution to society’s ills. Bad employers could be reformed, and class hostility avoided, through the influence of enlightened and empathetic women. In contrast, Carnie did not observe the working class from the outside; instead, she lived and breathed class conflict and advocated collective resistance to the whole capitalist system as the solution to class and gender inequality. No woman in Carnie’s novels could marry her way out of an oppressive system, and no employer was humanised by love. Her writings expressed the desire of working people for a share of the wealth they produced, for opportunities to experience joy, and for access to the beauties of nature and the inspirations of culture.

Carnie’s literary voice was that of working-class women from the North of England—something rarely heard in literary circles. She slipped into obscurity following her death in 1962, but recent critical interest in reviving the voices of working-class women writers has prompted a modest recovery of her reputation.5 The aim of this article is to build on this renewed interest and to place Carnie’s life and work in the context of British socialism in the early decades of the 20th century.

Radical roots

In the 19th century, Lancashire and West Yorkshire were centres of both the industrial revolution and of collective working-class resistance and organisation. Women played a key role in the production of textiles in these regions. At this time, many industries were segregated by gender, and women workers were often used by employers to undercut men’s wages. However, textile workers were paid according to a piece rate system, which meant a degree of gender equality in pay and conditions, and this facilitated the growth of trade union organisations involving both men and women. From the early 19th century, women played a role in all the region’s working-class organisations and struggles. The first so-called Female Reform Society appeared in Blackburn in July 1819, and women were prominent in the crowd and on the platform at St Peter’s Field on 16 August 1819 when the Yeoman Calvary charged a peaceful protest in what became known as the Peterloo Massacre. The female Chartists of the Lancashire and West Yorkshire textile districts were among the best organised and most militant in the entire Chartist movement. During the 1842 strike wave, inspired by Chartism, women were noted for their courage. Women were also central to the Preston Lockout of 1853-4 in Lancashire and were key activists in areas supporting the Northern states during the Civil War in the United States, despite the hardship associated with the cotton famine created by the blockade of the Southern slaveholding states by the Union. The fight for the female franchise also had deep roots in the labour movement in the Lancashire and West Yorkshire textile-producing areas, where women weavers and winders took their campaign to the factory gate and the cottage door.

Carnie was no isolated voice. Rather, she was representative of a huge number of working-class women who were active in the socialist movement in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Many of these women remain unknown, but one who did achieve prominence in Lancashire was Selina Cooper. Cooper was born in 1864 and moved to Barnoldswick, a town near Nelson in Lancashire, when she was a child. In 1876, at the age of twelve, she began working in the local textile mills. Cooper became involved in trade union activities and was an early member of the local branch of the Social Democratic Federation (SDF) in Nelson.6 She joined the North of England Society for Women’s Suffrage in 1900. The following year, she was elected to the local board of guardians, which was responsible for the administration of the Poor Law, as a joint candidate of the SDF and the Independent Labour Party (ILP).7 She grew frustrated with the SDF’s lack of interest in women’s campaign for the vote and became a full-time organiser for the female suffrage movement. This brief sketch of Cooper’s life illustrates the fluidity between different political organisations and campaigns at the turn of the 20th century, when Carnie herself entered the mill. Cooper lived in the same area as Carnie, and they were both resident in Nelson during the First World War. Both were involved with socialist politics, trade unionism and the female suffrage campaign. However, Cooper was primarily an organiser; in contrast, Carnie’s main contribution to the socialist cause came through her writing. Cooper was one of many women who created a rich and sustained tradition of female organisation and political activity, which was part of Carnie’s cultural inheritance.

Carnie was born on 1 January 1886, the daughter of David and Louisa Carnie, who both worked at the Vine Mill in the weaving town of Oswaldtwistle, near Burnley. She was born into a world dominated by cotton production. Mills in north eastern Lancashire produced 82 percent of all British exported cotton goods by the 1880s, and workers in those mills made a record seven billion yards of cloth in 1913.8 Burnley doubled its number of looms to 99,000 between 1886 and 1914, and weavers’ villages grew together to form small towns. By 1892, the Carnie family had moved into the town of Great Harwood, and Ethel began to work part time in the Delf Road mill. She also enrolled in the Great Harwood British School, which was regularly closed by outbreaks of scarlet fever, measles and ringworm. In 1899, at 13 years old, she left school and began working full time in the mill. She later recalled the impact of this work:

Factory life has crushed the childhood, youth and maturity of millions of men and women. It has ruined the health of those who would have been comparatively strong but for the unremitted toil and the evil atmosphere.9

Equally detrimental was the effect of monotonous toil and external discipline on the factory hands’ creativity, imagination and capacity for joy.

Carnie no longer had access to formal education, but she took advantage of the impressive collection of books held by the Great Harwood Co-operative Society Library. She smuggled books into the mill and read in quiet moments at her loom and in her precious free time.10 She began composing poetry while she worked, listening to the rhythm of the machinery surrounding her. Two of her poems were published in local papers in Blackburn, which had a thriving radical press with a tradition of devoting serious space to poetry.11 In 1906, the Cotton Factory Times called her the “poetess of the factory”, and her poem “The Bookworm” attracted attention from local poetry enthusiasts.12 When she read it aloud at Blackburn Author’s Society, those present were astonished that a teenaged mill girl was capable of writing such verses. These early poems were suffused with a sense of the prevailing class inequality, and this only grew stronger as her talent developed:

I own no grand baronial hall,

No pastures rich in waving corn;

Leave unto me my love for books,

And rank and wealth I laugh to scorn…

The world of books—how broad, how grand!

Within its volumes, dark and old,

What priceless gems of living thought

Their beauties to the mind unfold.13

Members of the society encouraged Carnie, and she published a volume called Rhymes from the Factory in 1907. It sold out of its initial print run of 500 copies, and a second edition was published.

Carnie’s political commitment grew alongside her poetic reputation. Her father was a member of the SDF, and he often took her along to meetings in Burnley when she was young.14 The SDF’s Burnley branch was one of the strongest and most dynamic in the country, perhaps because its members were committed to building unity with other socialist organisations. Great Harwood was in easy reach of both Burnley and Blackburn, and she became active in the ILP in Blackburn.

The inaugural ILP conference was held in Bradford in 1893, so the party had deep roots in West Yorkshire. Carnie’s choice of the ILP may have been a gesture of independence from her father, but there were few practical distinctions between socialists in the area. Both the SDF and ILP were formally committed to collective ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange, though the ILP put more emphasis on winning working-class parliamentary representation. Members of both groups worked, organised and socialised easily together and were buoyed by a similar sense of optimism. The 1906 general election saw a total of 12 socialist MPs elected in Lancashire, and Victor Grayson, an independent socialist, was elected MP for Colne Valley a year later. Possibilities for socialists to organise and grow seemed limitless, and writers had a recognised role in serving the cause of socialism.

Carnie’s 1907 edition of Rhymes from the Factory was reviewed favourably by James Keighley Snowdon, a socialist writer based in the West Yorkshire town of Keighley. Snowdon noted Carnie’s commitment to winning equality for the working class, choosing to highlight these lines:

If death be equal, why not also life?

Why should the toil, the suffering and the strife

Fall but to some?

Snowdon predicted that the unpolished nature of Carnie’s poetry would probably lead to her being dismissed by critics. Although he was broadly correct, Snowdon’s own review was read by an influential socialist, Robert Blatchford. In 1890, Blatchford had helped to establish the moderate Manchester Fabian Society, but by the mid-1890s he was gravitating first towards the more militant SDF and then the ILP. Blatchford’s most significant contribution to the socialist movement was his hugely influential newspaper, The Clarion, which sold an average of 50,000 copies a week in the first decade of the 20th century, peaking at 95,000 in 1908.15 Supporters of the paper were known as “Clarionettes”, and they established a national network of socialists. The Clarionettes formed their own clubs to discuss politics and pursue cultural and sporting interests, contributing to the creation of a vibrant and confident left-wing movement. Carnie was a keen Clarion supporter, and she joined the Clarion Café in the village of Roughlee, near Nelson. She took part in walks and cycling with like-minded socialists who sought to escape from the pollution and dreariness of life in the mills by exploring nature.

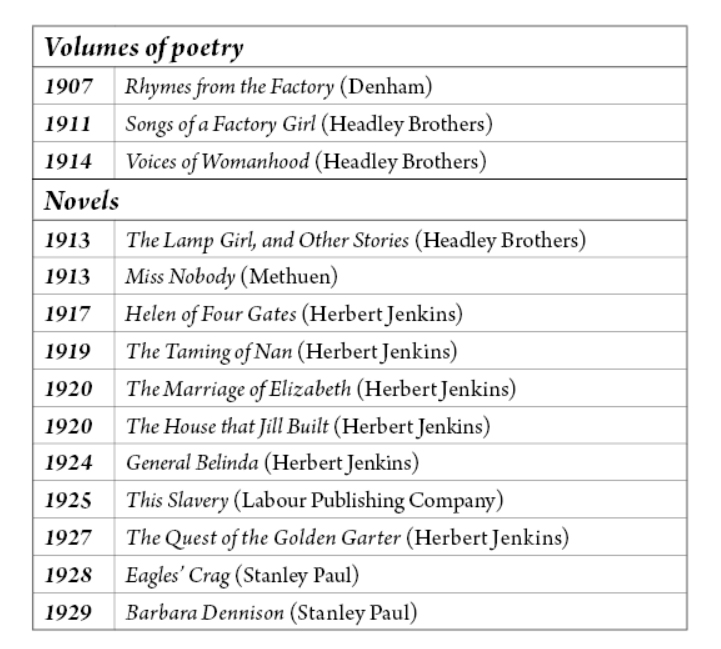

Table 1: Published works of Ethel Carnie Holdsworth

After reading Snowdon’s review of Carnie’s poetry, Blatchford visited her in July 1908. He published an account of their meeting in The Woman Worker, a new penny weekly launched in September 1907 as a companion to The Clarion. Blatchford reported that Carnie was free from airs, graces and affectations. He said she spoke with a strong Lancashire accent, rather patronisingly calling her the “Lancashire fairy”.16 Blatchford was not so enchanted with Great Harwood:

The Lancashire fairy lives at Great Harwood. Great Harwood is a monstrous agglomeration of ugly factories, of ugly gasometers, of ugly houses—brick boxes with slate lids. There is neither grace nor beauty in Great Harwood. It is the last place in which one would expect to find a poet.17

What Blatchford failed to grasp was that Carnie was not a poet despite her industrial home, but because of it. It was the unsightly mill towns and their impoverished inhabitants that inspired Carnie to write and to pose collective, militant alternatives to the ugly lives imposed on her community.

The Women Worker

Following their meeting, Blatchford invited Carnie to move to London so she could write for The Clarion and edit The Woman Worker. She accepted the invitation in July 1909. In London, Carnie joined a circle of female socialists that included Julia Dawson, who had edited the women’s section of The Clarion from 1895 and then The Woman Worker until Carnie took over. Dawson was the author of a popular 1908 pamphlet, entitled Why Women Want Socialism, and she pioneered the use of “Clarion vans”—horse-drawn coaches that were staffed entirely by women and travelled from town to town to distribute socialist literature and hold open air meetings. Speakers on these gruelling tours included female suffrage campaigners and trade unionists Caroline Martyn, Ada Nield and Sarah Reddish.18 The Clarion women also set up “Cinderella clubs”, which provided food and entertainment for poor children, and created the Clarion Handicraft Guild, based on William Morris’s ideas.

The editorials and articles Carnie wrote for The Woman Worker showed that she had no intention of confining herself to women’s issues. Instead, she asserted her right to engage directly with the government on a range of issues. She accused Edward Grey, secretary of state for foreign affairs, of failing to stop a Russian pogrom that left 29 Jews dead. She attacked Liberal Party chancellor David Lloyd George’s 1909 “people’s budget”, which financed welfare reform through raising taxes, as a half-hearted measure, arguing that the total eradication of the class system was needed instead. She criticised Labour MPs for timidly accepting the Liberals’ indifference to hungry children and voteless women.19 Carnie demanded the right to work, arguing that state support for the unemployed would increase worker’s confidence and could create a challenge to the labour market itself. She had little time for organised religion, writing:

Sunday is the only day we have to live our lives. Out of the house of bondage into the field of liberty. They did well to allow us this one day in the week in which to have a taste of home—otherwise we should have broken loose long since. Once I saw a picture of the crucified Christ. That wan brow, and anguished look—you need not go into a picture gallery to see it. Stand at the gates of a cotton factory at the end of a summer’s day, and see the operatives trail out! The little half-timer by the loom, straining to reach—with thin hands throwing the shuttle. You may see it there.20

Carnie addressed a wide range of political issues, campaigning energetically and consistently, for instance, to improve the lives of working-class children. However, she constantly returned to the question of the conditions endured by women workers and their double burden of housework and exploitation. She demanded equal pay and equal political and economic rights as well as defying convention by highlighting domestic violence. Despite being rarely talked about at the time, violence in the home was the subject of one of her poems, entitled “Shame”. She supported women’s right to vote, but she was also critical of the Women’s Social and Political Union because of the dictatorial leadership of Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst, their terrorist tactics and the organisation’s support for the vote for propertied women at the expense of working-class women. Carnie instead threw her support behind the Adult Suffrage Society, which advocated universal suffrage for both men and women. The Adult Suffrage Society attracted some of the most radical female suffragettes of the time. Its honorary secretary, Dora Montefiore, and the secretary of the Canning Town branch, Adelaide Knight, would both later become founding members of the Communist Party of Great Britain, which was established in 1920.21

With Carnie as editor, the circulation of The Woman Worker grew to between 25,000 and 26,000 copies a week.22 Despite this success, her increasingly militant political stance caused friction with Blatchford, whose socialism was inconsistent and contradictory. She criticised his support for British militarism and belligerence towards Germany, and he opposed her view that women were class fighters as well as homemakers. In January 1910, Blatchford changed the name of The Woman Worker to Women Folk, installing his daughter, Winifred Blatchford, as editor. Winifred filled the newspaper with advice on household management and how to educate children.

Fighting for freedom

Within a couple of weeks of this change, Carnie had returned to Great Harwood and was back in the mill. This was a contradictory experience. She hated the “narrow, monotonous, long day, the torture of the turning wheels, the whirling straps, the roar and rattle of the machinery when I have to come to my place sick with cold or tired with running last I should be late”.23 At the same time, she knew that it was the life of wage slavery that gave her a distinct voice and inspired her writing. She continued to contribute articles to Women Folk and published her second volume of poetry, Songs of a Factory Girl, in 1911. One of the poems from this volume, “A Marching Tune”, was later set to music by the suffragist and campaigner Ethel Smyth. This is the first verse:

The beat of the drums

And the sheen of the spears.

And red banners that toss like the sea,

Better far than the peace

That is fraught with deep death

To the wild rebel soul set in me;

Better pour out the blood in a swift crimson flood,

As to music we march to the grave,

Than to feel day by day the slow drops ebb away

From the chain-bitten heart of a slave.

In 1911, Carnie enthusiastically supported the creation of the British Socialist Party, believing it could unite England’s fractious socialist organisations. Between 1911 and 1913, Carnie enrolled at Owens College in Manchester, relying on both her wages and income from writing to pay the fees. She was committed to adult education but accused Ruskin College and the Worker’s Education Association of becoming tools of the establishment and argued that higher education must be refocused on the creation of revolutionaries.24

During these years, she lived with her mother in the Ancoats area of Manchester, which she found depressing. Yet, although the built environment was dreary, Carnie was excited by political developments. In 1913, she was engaged in raising support for the workers involved in the Dublin Lockout, an event that galvanised the English labour movement and the left wing of the women’s suffrage movement. For example, Montefiore was investigated by the police for child kidnapping when she tried to organise the evacuation of the Dublin workers’ children to families who could feed and care for them.25 However, the class struggle exposed some of the political tensions emerging in the suffrage movement; when Sylvia Pankhurst spoke alongside James Connolly at a solidarity rally in London, her mother, Emmeline Pankhurst, expelled her from the Women’s Social and Political Union. Socialists like Carnie, Montefiore and Sylvia Pankhurst stood on the side of the Irish workers, and Pankhurst took this fight into London’s East End. There is no evidence of a friendship between Sylvia and Carnie, who shared their strong commitment to socialism, but Pankhurst did publish one of Carnie’s poems, “A Vision”, in her newspaper, The Women’s Dreadnought, in December 1914.26

While in Manchester, Carnie decided to advance the cause of socialism by writing novels and contributing to a long tradition of fiction that aimed at explaining, justifying and advocating for reform. In the mid-19th century authors such as Frances Milton Trollope, Ernest Charles Jones and Charlotte Elizabeth Tonna adopted popular genres such as melodrama and reworked them to express the political concerns of a working-class audience. Carnie used melodramatic conventions to express hostility to class inequality in her first novel, Miss Nobody, which was published in 1913. The central character, Carrie Brown, is an orphaned factory worker who marries a farmer to escape her hard life. She copes with jealous relatives and the petty, boring nature of village life and leads a strike in her factory. Her marriage is failing when her husband is wrongly accused of murder, but the experience of fighting for justice pulls them together. The couple spend the rest of their days supporting working-class women with an unexpected inheritance from Carrie’s long-lost father. The novel’s improbable plot created the space for Carnie to articulate a critique of inequality and poverty and to explore the difficulties of sustaining a loving relationship in the face of monotonous and exhausting labour. The Times Literary Supplement gave the novel a very favourable review, constituting a very rare appreciation of an obscure, northern, female author in a respected national publication. The reviewer described Carnie’s depictions of factory life as “wonderfully powerful and vivid”.27 Carnie’s novel has been described as a conventional romance in which marriage across classes represents a wider class reconciliation.28 In fact, Miss Nobody was a clear and unapologetic attempt to promote socialist ideas to a wider audience.

In July 1913, socialist educationalist Mary Bridges-Adams placed an advert in Justice, the newspaper of the SDF, promoting a residential adult women’s college that would equip its students to play a constructive role in the labour and socialist movements. Carnie, who had never really taken to life in Ancoats, returned to London to take up a post at the college, teaching women how to advance the cause of socialism through writing. The college, located in London, was named Bebel House in tribute to the recently deceased German Social Democratic Party leader August Bebel, whose Women Under Socialism was one of the foundational texts in the Marxist analysis of women’s oppression. Bebel House and Carnie’s Rebel Pen Club were advertised regularly in the women’s suffrage paper, The Common Cause, where Carnie explained the rationale behind her club:

Literature is to a large extent lop-sided, inasmuch as hundreds of working-class women who might have done so have not expressed themselves; though, with sympathetic assistance, they might have held up a mirror to corners of life unseen by the many superior persons who, with feebleness exceeded only by their “good intentions”, have shown the necessity that the workers should speak for themselves.29

Unfortunately for Carnie, the college never attracted enough sponsorship or students and was forced to close. She returned to Lancashire, where she made a living selling ribbons and lace in Blackburn market. She must have reflected on the irony of a fierce tribune of women’s equality being forced to make a living selling the fripperies that symbolised the trivialisation of women’s aspirations.

By 1914, Carnie was a committed Marxist who believed that only class struggle could liberate the working class from exploitation and oppression. Her poetry from this period, published in the volume Voices of Womanhood, dramatises working-class women’s lives and criticises art that ignores class divisions.30 In the prelude, Carnie looks to revolutionary voices to bring the dream of socialism to fruition. These “voices impetuous, daring and wild” were “blazing new trails”:

What shall a poet give? Shall it be tears?

I, as you pass, unashamed and afraid,

Out from the silence to cry against wrong

Wave Song’s bright banner and smile that the world

Yet has its heroes so splendidly strong.31

Her journey to political and artistic maturity was both individual and collective. Among the collective experiences that shaped her political development were the militant women’s suffrage movement and the upsurge of industrial militancy during the Great Unrest, which lasted from 1911 until the outbreak of the First World War. The Great Unrest involved around 3,000 strikes as well as mass confrontations between strikers and the police. Many of the workers involved were un-unionised, and this included lots of women. The most visible female suffrage organisation, the Women’s Social and Political Union, opposed the strikes, arguing that their own militant actions were superior to “male” industrial unrest. When around 15,000 female factory workers in Bermondsey in South East London walked out on strike, the Women’s Social and Political Union told them to focus exclusively on the fight for the vote.32 Some radical suffragettes, including Eva Gore-Booth and Esther Roper, worked to draw working-class women into the suffrage movement, but they were in the minority among the leadership of the national suffrage organisations.

Women’s suffrage organisations tended to stand aloof from the labour movement, and socialist organisations were suspicious of making special efforts to appeal to women workers. Many women were inspired by the class struggle and joined trade unions, but the unions made little effort to support women’s right to vote or to challenge gender equality more widely. Socialist women such as Montefiore and Selina Cooper fought consistently to get socialist organisations like the SDF to devote more effort to bettering women’s conditions, but this met with mixed success. Carnie supported both women’s suffrage and gender equality and the working-class revolt. Indeed, she associated with all the major socialist organisations of her day, although she never committed fully to any of them.

In 1914, socialists across Europe faced a great test of their commitment to internationalism. War broke out in August, prompting a wave of nationalism and patriotism that overwhelmed many of the big parties of European socialism. Carnie was one of the small number of activists who stood against the stream and opposed the war. She married a local poet, Alfred Holdsworth, at Blackburn’s registry office in April 1915, becoming known as Ethel Carnie Holdsworth, and the couple began organising anti-war sentiment into a movement. Carnie shunned the existing anti-war organisations and campaigns, even though she was now living in Nelson, a town with a radical anti-war movement led by Cooper. Instead, Carnie became an organiser for the British Citizen Party (BCP) and started writing for its newspaper, British Citizen.33 BCP activists in Lancashire campaigned vigorously against the introduction of conscription in 1915 and 1916 in spite of threats and physical confrontations. On 30 November 1915, the BCP held a meeting at a school in Nelson, and around 1,000 people attended, with Carnie in the chair. A troop of the Colne Volunteer Corp, who were training nearby, attacked the meeting. Carnie leapt to the piano and led a rousing rendition of “The Red Flag”, but it took over an hour for stewards to restore order.

Despite the protests, conscription was introduced in January 1916. Carnie’s husband applied for an exemption under the law but was refused. Nonetheless, he was allowed to go to the Western front in a non-combat role.34 The ever-defiant Carnie accompanied Holdsworth to the station waving a red flag. She was left to care for her baby, Margaret, alone. As usual, she turned her experience into a political lesson, writing a series called “Women and War” for a local newspaper, where she debunked the glorification of war, stressing the psychological and physical suffering of soldiers’ wives and mothers.

In 1917, Carnie published Helen of Four Gates, her most successful novel. The book was compared to Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights because of its moorland setting and daring focus on domestic violence and marital rape. It sold 33,000 copies and was made into a silent film in 1920, directed by Cecil Hepworth and starring a popular actor, Alma Taylor.35 The picture was filmed on the moors between Hebden Bridge and Haworth, a stone’s throw from the moors above Haworth where Wuthering Heights was set. The success of Helen of Four Gates gave Carnie the funds to buy a farmhouse in the West Yorkshire countryside between Todmorden and Hebden Bridge.36

The Representation of the People Act 1918 gave women over 21 the vote, but only if they paid rates on property they owned, which excluded servants, women living with relatives and those who rented their home, as Carnie did. In the same year, she was officially informed that her husband had been killed in combat. It took a year before she found out that he was very much alive in a prisoner of war camp. In 1919, the couple was reunited and moved to Heptonstall, a village on the hill above Hebden Bridge, where their second daughter, Maud, was born. The change must have suited Carnie because she published three novels the following year: The Taming of Nan, The Marriage of Elizabeth and The House that Jill Built. All these novels were romances set amid the harsh realities of life in Lancashire’s textile towns, with characters who experience industrial injury, domestic violence, and the corrosive effects of the poverty and inequalities that women endured. The Holdsworths also visited London in 1920, which may have been prompted by the formation of the Communist Party of Great Britain. Carnie’s husband joined the Communist Party, as did a group of women who, like Carnie, had supported the adult suffrage campaign, including Dora Montefiore, Adelaide Knight and Sylvia Pankhurst. However, there is no evidence that Carnie formally joined the party. She did, nonetheless, issue the following statement in Women’s Outlook:

I look more and more to the solidarity of the workers of all countries for the solving of the wrongs of poverty and war; I believe wholeheartedly in the dictatorship of the proletariat, which means the holding down by the worker of those who have so long wronged the worker until chaos changes to order and the disorder of classes is transformed into the order of humanity.37

Despite this public statement of support, she remained a fellow traveller of the Communists rather than an active member.

The Clear Light

From 1923, Carnie and her husband began producing a radical magazine, which they entitled The Clear Light, from their living room at Robertshaw Farm, Slack, above Heptonstall. An advert for The Clear Light asserted that “the revolution is on NOW, and that it will be bloodless up to the point of open, active counter-revolution”.38 In the new publication, Carnie argued that a Labour government would be unable to win the thorough-going reform workers needed. As an alternative she advocated the creation of a “citizen army” to challenge the power of the state and prepare for a revolution.39 In October 1924, The Clear Light shifted its focus to a new threat: the emergence of fascism. Unemployment and insecurity created the basis for British fascists to begin to organise, hoping to follow the example set by Benito Mussolini in Italy, who had come to power in 1922. First came The Britons and then the much more threatening British Fascisti, whose supporters paraded in military uniforms and attacked socialist and Labour Party meetings. Carnie and her husband relaunched The Clear Light, this time as the organ of the National Union for Combating Fascism, which had Carnie as its organiser.40 The Clear Light attracted a significant readership, but Carnie’s strategy of refusing all advertising in order to stay independent meant it was impossible to keep the publication going. However, the couple did succeed in establishing a model of anti-fascist propaganda and organisation that was followed by activists in the 1930s, when the threat from fascism became more obvious.

Throughout the 1920s, Carnie combined her political activism with promoting socialism through her poetry and novels. Like so many British radicals, Carnie was inspired by the early 19th century revolutionary poet Percy Bysshe Shelley. Her 1923 poem “The Carnival of State” is an allegory that directly references Shelley’s “Masque of Anarchy”, which he wrote in the aftermath of the Peterloo Massacre in 1819. Carnie’s poem is an unequivocal condemnation of the capitalist system and the institutions that justify and legitimise its rule. Parliamentary democracy features as a hypocrite propping up exploitation. The impoverished workers are fearful of losing what little they have and are constantly told to be thrifty and manage their budgets more efficiently. Neither strikes nor pacifism are powerful enough to challenge capitalism, which is only threatened when courage unites with thought, dreams and passion. Working-class people can remake society if they use their capacity to think, imagine a different future, engage their emotions and learn to be fearless:

First came Tradition, ancient and stumbling

On gouty feet—her glory crumbling

With vile, blood-rotted banner flying

O’er Monarchy, senile, half-dying

His new name (Democracy) proclaiming.

Wire pulled (too weak for human blaming)

Swordless and voiceless, a crowned dummy

Droning a speech—galvanised mummy!

Whilst all about, admiring flunkies

Half-proved the theory about monkeys.

Next—a grim hangman, scarcely human,

Dragged to the rope a drooping woman,

And, safe (behind), strutted Lord Curzon,

Blowing War’s trumpet—ribbons—spurs on.

There went the traitor Mussolini,

Aping a look like grand Mazzini

Upon his vest of blood-soaked darkness

An English crest gleamed in its starkness…

There amble Thrift, rattling scant savings,

Answering the breadless with wild ravings,

Mumbling a litany against wasting,

Licking dry lips that ne’er had tasting

Of one great hour with Joy full-crowded

Coffined and meagre and living shrouded.

Then Proletarian Life came walking

With anxious love, of prices talking

Their children, Fear and Want and Striving…

Then went the strike, all fierce and haggard,

Shouting of wages: and that laggard

Meek Pacificism, all negation

Whilst nation made arms against nation,

And hounds of war shouted in wonder

For aeroplanes—with blood and thunder.

There walked the Soldier, left unlettered,

With all his ignorance, slave fettered,

For to give him erudition

Would bring the menace of sedition.

O motely throng! O forms of all shameless!

Go by, go by! Some shall be nameless.

For off in the rain our Freedom waiteth,

Her hour shall come when Courage mateth

With Thought and Dream and holy Passion,

And other carnivals gain Fashion.

In 1924, Carnie published a fictionalised account of her experiences of the war entitled General Belinda, in which she made clear that all the soldiers—of whatever nationality—were the sons of somebody and that conscripts of all countries were victims of capitalism’s rapacious drive for profit.

The first Labour Party government, a minority administration, was formed in January 1924 after the December 1923 general election failed to produce a majority. This government appeared to offer a breakthrough for working-class people seeking redress for unemployment and poverty. Historian Richard Smalley’s biography of Carnie suggests her home in Hepstonstall had become an organisational headquarters of the local Labour Party by 1925, the year that her husband joined the party. Smalley argues that Carnie also probably joined the party that year, although the first documented suggestion of her having become a member was in a Labour Party publication in 1927. Smalley points to a passage from the last edition of The Clear Light, published in 1924, in order to support his view: “More and more I am driven to the conclusion that democracies can never be won save by enlightened, determined and uncompromising majorities”.41 However, I can find no evidence that Carnie had changed her long-held view that Labour was too timid and too prepared to compromise with the establishment. In February 1924, just weeks after the installation of the new government under Ramsey MacDonald, she published “Labour’s Magnificat”, which reasserted the revolutionary alternative to the political prison of Labour:

Out of the house of bondage and of shame,

Leaping and shouting, singing wild I come,

Singing the songs I dreamed when blind and dumb,

The brands upon my brow now radiant flame.

For from this prison house of coward clay,

Bursting corruptions’ bonds, unsmirched and whole,

I free myself and sing—no captive soul

But one that hurls its cankering chains away.

Now my slow patient tears and long despairs,

Burst into flaming blossoms, as the staff

Flowered, ‘gainst all Power’s decree, to fires of Spring.

Now my forbearance, agonies and prayers

Bring the great harvest, casting out the chaff.

I who have sown your power—the sickle swing.42

It is true that Carnie became disillusioned with the limitation of democracy in Soviet Russia, failing to acknowledge the enormous efforts that had been required to defend the revolution from hostile foreign armies, blockades and counter-revolutionaries. However, in October 1924, she wrote to Freedom, an anarchist newspaper that was publicising cases of anarchists imprisoned in the Soviet Union, to clarify her political independence:

I do not belong to any anarchist group or any other group. I belong to the folk—from the undeveloped and illiterate, so confused that they are the bedrock of even reaction, to Walt Whitman and William Morris, and Karl Marx, Peter Kropotkin and Mikhail Bakunin.43

Carnie offered to write poems that could “sing of the indignities” of prisoners, whatever their beliefs. She wrote “Power” to champion the cause of dissent in Russia, but it also speaks to all those repressed by capitalism and the economic, political and ideological institutions reinforcing its dominance:

They built the house of Power on Force and Fear,

And gave authority the key to hold,

Stamping it with the hallmark of dead gold,

And rusting it in human Blood and Tear.

“Behold!” cried Power, “The glory of my state!

Here I conserve forever all that Is,

Here, manacled and gagged, my priests shall kiss

My sceptre. Prisons, dungeons, be my Gate!

Whilst outside millions claw and scratch for Bread,

And burdened lives go swiftly to the grave.

Hold fast my key, my mistress, and all’s well!

But Liberty came by with rose-crowned head,

And piped upon her pipe to every slave

These words of Laughter, “Fear is all their spell.”44

In December 1924, Carnie wrote to Freedom again, arguing that Labour supporters, Communists, socialists and anarchists should bury their political differences and unite ahead of the time when capitalism would be overthrown in Britain. Her position was perhaps naive, and she underestimated the importance of political clarity. However, her instinctive challenge to sectarian divisions and support for unity was understandable in the context of the fluid relationships between socialists of all different persuasions. In the 1920s, the Communist Party of Great Britain pursued a tactic of applying for affiliation to Labour Party. Although this application was rejected, individual Communists did join Labour, and some were elected to office on Labour tickets. Many socialists were members of both parties, and many others, such as Carnie, supported different aspects of the various political programmes on offer, seeing no contradiction between their sympathies for the Russian Revolution and the first Labour government in Britain. The Labour Party government survived until October 1924, when it was defeated after a general election campaign dominated by the Daily Mail’s publication of the forged “Zinoviev Letter”. This document, purporting to be a directive from Grigori Zinoviev, the president of the Communist International, ordered the Communist Party of Great Britain to foment insurrection in the armed forces and claimed a Labour government would open the way for socialist revolution in Britain. The panic caused by the letter helped Stanley Baldwin’s Conservatives to electoral victory.

The failure of Labour in office and the dirty tricks played by the establishment fuelled Carnie’s condemnation of the ruling class. In 1925, she published a second powerful poetic reply to Shelley. This time she responded to his “Ozymandias”, a poem depicting the ultimate futility of imperial authority. Carnie continued Shelley’s theme and added a new dimension. In her poem, the kings looked powerful because their subjects were “slaves of that power”; the subjects believed in the greatness of their rulers, thus perpetuating their might. Thus, when people became aware of the true nature of class power, they could begin to dismantle it:

Who was great Ozymandias, “king of kings”?

The desert answers with its fiery breath.

Democracy of Time, and Space, and Death

Its fatal arrow at Great Nothing flings.

Law, Force and Power—dark Superstition’s blight,

And all the majesty of sword and chain

Left but his futile image to remain

Half-buried where the sandstorm whirls in flight.

Feebler and feebler grow the decadent line

Which followed on that mightiest Nothingness,

Slave of that Power wherein his weakness lay,

Whom only Human Ignorance held “divine”.

With every reasoned thought their shades grow less,

To vanish in the light of ampler day.45

As well as her version of Ozymandias, Carnie also published This Slavery in 1925. This is an extraordinary novel that attempted to popularise Marxist ideas about the irreconcilable class struggle and the systematic oppression of women. She may have been becoming disillusioned with the course of the Russian Revolution, but this novel demonstrates that she still had faith in revolutionary politics. This Slavery is a compelling socialist tale of love, loss, poverty and politics with women at its centre. It tells the story of two sisters, mill girls Hester and Rachel Martin, whose lives are thrown into turmoil when a fire at the mill leaves them both unemployed. The poverty of their domestic life deepens, and the girls are forced to reckon with the difficulties of their economic circumstances. They make romantic and political choices that will place them on opposite sides of the great class divide; Hester enters a loveless marriage with a mill master, and Rachel becomes a trade union organiser.

At the climax of the novel the workers starve in a bitter strike, and Rachel discovers that her mother had a sexual relationship outside of marriage. This prompts a great feminist speech:

I believe our morals are determined by our necessity an’ the economic conditions we live under. I don’t see sex is any more sacred than genius, and to sell one had no more ill effects than to sell th’ other. I wonder when women’ll be free, mother? An’ chaps, too, of course. But we, we somehow have a tradition behind us beside an economic slavery. We’ve got the race on our shoulders an’ all this other besides. An’ all they think we’re fit for down at the SDF yonder is to cook a thumping big potato pie when there’s a social or go round canvassing the names when a councillor puts up.46

Women’s capacity to challenge sexual double standards and misogynistic assumptions is bound up with their capacity to organise collectively as workers.

In This Slavery, it is a woman, Rachel, who criticises the economistic narrowness of many trade unionists, reads Marx’s Capital and dreams of a socialist future. Less lyrical but more compelling than her dreams are the novel’s small realist details, for example, of women’s tiredness and of hunger: “We seem to do nothing but talk and think about grub… Our bodies get in the way. We’re a set of pigs kept grovelling in the ground.” Or in ironical reflections on workers’ endurance: “To starve quietly, unobtrusively and without demonstration, is perhaps the greatest art civilisation has forced on the masses.” This brilliant and accessible novel deserves to be read by socialists today.

The novel received a poor review in The Sunday Worker, a newspaper that was aimed at left-wing members of Labour party who sympathised with the Communist Party of Great Britain and was very much in tune with Carnie’s outlook at the time. In the review, Tommy Jackson accused Carnie of “bourgeois tendencies” because her novel used romance as a vehicle for promoting socialist revolution. Carnie replied that Jackson might find romance among the proletariat if he knew where to look for it.47 Jackson’s patronising review was typical of the way critics of all political persuasions dismissed Carnie’s writing. Socialists like Jackson were suspicious of Carnie’s focus on women’s relationships and the inequalities they even faced within socialist organisations. Mainstream reviewers were hostile to her overt political stance. Yet, her novels found an audience among working-class women, whose lives she depicted so powerfully.

There were no happy endings in Carnie’s novels or in her own life. She separated from Holdsworth in 1926 and moved to Manchester. Her last published novel was Barbara Dennison, which detailed the ruinous effect of marriage on two couples and the violence that geminates in unhappy relationships. This may have been a reflection on her own marriage.

Carnie’s powerful reports of the Barnoldswick strike in March 1926 were published in The Sunday Worker. Some 50 weavers in the Lancashire town of Barnoldswick had gone on strike, escalating into a lockout involving 5,000 weavers who stayed out for two weeks. Two months later, the General Strike broke out, and Carnie became involved in the Workers’ Theatre Movement, which was closely associated with the Communist Party of Great Britain. The Lancashire group were known as the Red Megaphones and sought to generate support for the General Strike by dramatising scenes of class struggle. The plays were collaborative, so it is impossible to identify which were written by Carnie, but she recalled how reading and helping to write the plays was “important work”.48

Carnie was 45 years old when Eagles’ Crag, her last novel, was published. She wrote a few short stories and poems over the next few years, but she appears to have published very little after the age of 50. She was possibly disillusioned by the failures of the minority Labour government elected in 1929, which cut budgets and wages, ultimately leading to its own collapse. After another election in 1931, MacDonald became prime minister in the National Government with Baldwin’s Tories, which many socialists such as Carnie considered to be a great betrayal. Carnie’s parents died in the early 1930s, and her health declined. She was not immune from the exhaustion of working, child-rearing and constant opposition to the system she described in her novels. Margaret Holdsworth, her daughter, later reported to labour historian Ruth Frow that Carnie had felt “worn out” and demoralised by the rise of fascism.49 Smalley suggests that she may have been supported by her daughters, who both worked, until she was eligible for her state pension. Carnie died in 1962, and she was buried in the non-conformist section of Blackley Cemetery in Manchester.

Legacies: where is Ethel Carnie Holdsworth today?

For around five decades, rediscovering and promoting the work of women writers “abandoned” by critics and literary institutions has been a staple of literary feminists. The reason why Carnie has not yet proved an attractive prospect for such literacy recovery is that she was trenchantly working class. She wrote stories for and about other working-class women—women who, like herself, were already working long hours in factories and at home. With no allowance to free up her time, nor a high level of formal education, she had an urgent need to show how things were for herself and women like her. Her novels focused on working-class women and their struggles to survive, to organise collectively against the bosses and capitalism, and to remain optimistic. Carnie insisted that socialism could never triumph if it did not involve powerful and assertive working-class women and if it did not aim to enrich every aspect of life. At its best, her writing demonstrated that, in the words of her poem “Civilisation”, “Labour and love and art walk hand in hand”.50

For all Carnie’s disappointment with the rise of Stalinism, disillusion with Labour in office and hatred of fascism, she never gave up hope that the working class could fight for a better world. She may have retreated from public view, but she never became cynical or conservative. She developed an inspiring poetic vision of socialism, “working for pleasure instead of money, serving for the sake of service and not personal gain, loving for loving’s sake and not for a house in Hanover Square, giving oneself as the leaves give their shade to shelter the swallow’s nest”.51 Carnie has been wrongly overlooked, patronised and underestimated. She used her writer’s craft to stir working-class resistance to capitalism, especially among women. Her voice has never been more relevant or more deserving of recognition.

Judy Cox is a teacher in East London. She is studying for a PhD in women and the Chartist movement at the University of Leeds. She is the author of The Women’s Revolution: Russia 1905-1917 (Haymarket, 2019) and Rebellious Daughters of History (Redwords, 2020).

Notes

1 Carnie Holdsworth, 1914.

2 Thanks to Joseph Choonara, Richard Donnelly and Rob Hoveman for their comments on drafts of this article.

3 Webb, 2012.

4 Johnson, 2005.

5 Flood, 2021.

6 The SDF, founded by Henry Hyndman in 1881, was the first organised socialist political party in Britain. Members included artist William Morris, Irish republican leader James Connolly, future Labour Party leader George Lansbury and activist Eleanor Marx.

7 The ILP was established in 1893 and reflected dissatisfaction with the Liberal Party’s reluctance to support working-class candidates. Keir Hardy, a sitting independent MP and well known union organiser, was its first chairman. The party was positioned to the left of Ramsay MacDonald’s Labour Representation Committee, which was founded in 1900 and soon renamed the Labour Party. The ILP was affiliated to the Labour Party from 1906 until 1932.

8 Smalley, 2014, p7.

9 Smalley, 2014, p9.

10 Smalley, 2014, p12.

11 Frow and Frow, 2018, p252.

12 Cotton Factory Times (24 August 1906).

13 Frow and Frow, 2018, p253.

14 Frow and Frow, 2018, p252.

15 Smalley, 2014, p17.

16 Blatchford, 1908.

17 Frow and Frow, 2018, p254.

18 Martyn was a Christian socialist and an early organiser of trade unions in England. Nield was a socialist and suffragist who worked in a factory before being employed by the ILP and then within the women’s suffrage movement; her name is inscribed on the plinth of the statue of Millicent Fawcett in Parliament Square in London along with 59 others associated with the female suffrage movement. Reddish was a trade unionist and suffragette who, as a textile worker, experienced the real conditions of working-class women before becoming a union official.

19 Smalley, 2014, p25.

20 Carnie Holdsworth, 1909.

21 Montefiore was an English-Australian suffragist, socialist, poet and author. Knight joined the Women’s Social and Political Union in 1905, becoming its branch secretary in Canning Town, the organisation’s first branch in East London. She was imprisoned several times for her suffrage activities. She joined the central committee of the Women’s Social and Political Union but left the group in 1907.

22 Frow and Frow, 2018, p254.

23 Frow and Frow, 2018, p259.

24 Cotton Factory Times (3 April 1914).

25 Smalley, 2014, p50.

26 Woman’s Dreadnought (26 December 1914).

27 Smalley, 2014, p53.

28 Smalley, 2014, p54.

29 The Common Cause (19 September 1913).

30 Johnson, 2005.

31 Quoted in Johnson, 2005.

32 Darlington, 2020.

33 Smalley, 2014, p63.

34 Smalley, 2014, p65.

35 Smalley, 2014, p68.

36 The film is available to watch at https://archive.org/details/helenofthefourgates

37 Smalley, 2014, pp87-88.

38 Forward (20 October 1923).

39 Smalley, 2014, p94.

40 Smalley, 2014, p96.

41 Smalley, 2014, p117.

42 Smalley, 2014, p99.

43 Freedom (1 October 1924).

44 Freedom (1 May 1925).

45 Freedom (1 June 1925).

46 Carnie, 2011, p54.

47 Smalley, 2014, pp117-118.

48 Smalley, 2014, p123.

49 Smalley, 2014, p125.

50 Johnson, 2005.

51 Smalley, 2014, p26.

References