The racist system that governs the lives of everyone who lives within the borders of historic Palestine has increasingly been labelled a form of “apartheid”, recalling the oppression of the black majority in South Africa.1 This analysis of the Israeli political system has not just been adopted by Palestinian movements and solidarity activists, but has recently been boosted by a high profile report by the United States’s liberal Human Rights Watch organisation.2 It is also accepted by prominent Israeli human rights organisation B’Tselem, which has described Palestine as being ruled by a regime of “Jewish supremacy from the River Jordan to the Mediterranean Sea”.3 At the core of the arguments advanced by Human Rights Watch and B’Tselem is a recognition that one state, the Israeli state, holds sovereignty across historic Palestine and that it governs Palestinians and Israelis differently and unequally according to their national origin. The unequal treatment of Palestinians on this basis holds true regardless of whether they are citizens of Israel or residents of the Occupied Territories. Moreover, because the State of Israel accords full citizenship rights only to members of a group that is defined in religious and ethnic terms (“the Jewish people”), there is no way that Palestinians can ever escape from their place in this hierarchy.4

This article concentrates on exploring two paradoxes. First, how did a political system justified by an ideology of explicit racial hierarchy manage to survive the end of the colonial order in the wake of the Second World War? Why did the experience of antisemitic persecution and genocide of Jewish communities in Europe—which was also mobilised by Zionist activists to justify the creation of an exclusively Jewish state—not undermine that ideology? Unlike liberal approaches to the question, the analysis presented here does not focus on political forms. Instead, it examines how the development of capitalism within the bounds of the national economy of historic Palestine, the wider regional economy and at a global level has sustained both the Zionist settler colonial project and the specific racist institutions that oppress Palestinians on a daily basis. In particular, it will argue that the dynamics of imperialist competition in the region are the prime motive forces that allow the Israeli ruling class to continue operating an apartheid system. Alex Callinicos notes that South African apartheid was more than simply a “particularly barbarous form of racial domination”, but rather the “particular form in which capitalism developed” there.5 The same is true of Israeli apartheid.

However, this leads us to consider a second paradox: how and why does Palestinian resistance sustain itself in the face of overwhelming pressure from this highly militarised state? The general strike on 18 May 2021 provides an example of how the Palestinian mass movement has been able to renew itself despite repression and repeated military onslaughts. This is a process which has repeated itself across successive generations both in exile and within historic Palestine. This article will examine the roots of the strike, but it also argues that we have to look more deeply at the social dimensions of the Palestinian struggle in order to understand why it remains a source of inspiration to millions around the world and a symbol of resistance to injustice and oppression. Specifically, it is the reciprocal action (and occasional fusion) between the social aspect of the Palestinian struggle and its political aspect that underlies the persistence of the Palestinian resistance as a mass movement. The peaks of Palestinian mobilisation since the Nakba are frequently depicted as episodes in a political (and military) struggle for national liberation and statehood; nevertheless, in every major case it was the collective energies of the poor and the working-class majority of Palestinians, in exile and inside historic Palestine, that provided the engine for the struggle.6

Despite this, the Palestinian working class has been fragmented through ethnic cleansing, and the Israeli ruling class can rely on sources of funding for the machinery of repression and war that are largely independent of the exploitation of Palestinian labour. For these reasons, the only resolution to these paradoxes that can bring lasting justice and peace for the majority in historic Palestine lies in re-activating the processes of social revolution at a regional level. The fight to enlarge and expand the social soul of the Palestinian revolution must develop in tandem with the rebuilding of revolutionary movements across the region (especially in Egypt, Lebanon and Jordan). This does not mean abandoning or deferring the quest for national liberation—rather it means recognising that achieving this goal depends on deepening that social struggle.

A settler-colonial garrison in a new imperial order

Although forms of institutional racism are structured into every capitalist society, there are few contemporary states that operate so openly according to principles of ethno-religious hierarchy as Israel. Seeing this as a legacy of the colonial era provides a partial explanation, but cannot explain why the apartheid system created by the Israeli ruling class has survived so long. The first issue to explore here is the relationship between the global dynamics of imperialism and the Zionist state-building project. Of course, this relationship pre-dates the foundation of the Israeli state: without the support of the British ruling class, the Zionist colony could never have established itself in Palestine in the first place.7 However, this article will concentrate on the integration of the Israeli state into the new imperial order constructed by the US in the post-Second World War period. Of particular importance here is how the dynamics of this system channel vast amounts of military hardware and funding into and through the Israeli state and economy. The ebbs and flows of imperialist competition between the US and its rivals have also sustained Israel as a settler-colonial society long after the collapse of similar political projects elsewhere.

We will analyse the role played by the massive influx of immigrants from the decaying Soviet Union in rebooting Israeli apartheid after the 1990s in more detail below. This is an example of conflicts between the global powers feeding into the particular forms of the Israeli state and the political economy of apartheid in historic Palestine. Just as in the 1930s and 1940s, when racist immigration policies prevented Jewish refugees from Nazi genocide finding safety in Britain and the US, the major imperialist powers weaponised the experience of discrimination and persecution by Jewish communities in the former Soviet Union to perpetuate their domination of the Middle East.

Such processes at the level of the world capitalist system continue to translate themselves into the institutions and ideology that sustains the Zionist project in Palestine because the founders of the Israeli state pulled off a spectacular coup. They forged a long-lasting partnership with the US ruling class that secured US protection for the Israeli state. This protection included not only the confirmation of its initial land grab and ethnic cleansing but also the legitimation and perpetuation of its racist system of government. Ha’aretz pinpointed the specific nature of Israel’s role as long ago as 1951:

Israel is to become the watchdog. There is no fear that Israel will undertake any aggressive policy towards the Arab states when this would explicitly contradict the wishes of the US and Britain. However, if for any reasons the Western powers should sometimes prefer to close their eyes, Israel could be relied upon to punish one or several neighbouring states whose discourtesy to the West went beyond the bounds of the permissible.8

Five years later, Israel’s role in the British and French attack on Egypt—an attempt to “punish” nationalist leader Gamal Abdel-Nasser for nationalising the Suez Canal—was the first major test of this approach. Later, victory over Egyptian and Syrian forces in the Six Day War of June 1967 set the “watchdog state” definitively on the path from aspiring “hired muscle” to fully fledged junior partner of the major Western imperial power.

The massive acceleration of US military and economic aid to Israel during the 1970s and its maintenance at incredibly high levels ever since is central to the political economy of the Zionist project. These huge subsidies turned the “burden” of military spending into a means to attract further external sources of funding and fundamentally shaped the class structure of Israeli society in the process.9 They also played a key role in laying the basis for the boom in high-tech and research-intensive manufacturing and services that has been central to the growth of the Israeli economy since the 1990s, as we will discuss below.

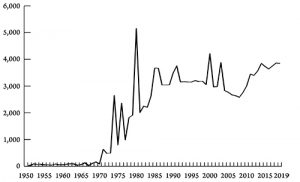

Figure 1: US foreign aid to Israel (millions of dollars)*

Source: Jewish Virtual Library.

* Constant US dollars (2018), inflation-adjusted.

Israel’s military economy is integral to the wider imperialist system that the US has sustained in the region during its period of global dominance. Israel’s “Qualitative Military Edge” over the other regional powers (including other US allies) is deeply embedded in this structure. The importance of Israel’s role, and the unwillingness of the US to rein in the Israeli ruling class or force it to allow the emergence of even a weak and stunted Palestinian state, is underscored by the failure of the “peace process” of the 1990s to bring any reduction in the level of US military aid to Israel. In fact, by the end of the 1990s, the US had initiated the first of three 10 year long Memoranda of Understanding (MoU), binding successive Republican and Democrat US administrations to continuing to transfer astronomical levels of funding, weapons and technology to Israel.10 A key clause in the MoUs allows Israel, uniquely among recipients of US military aid worldwide, to spend this aid in its own currency, thus effectively underwriting Israeli military industries with US taxpayers’ money.

Just another “army with a state”?

US military might alone is insufficient to guarantee the interests of the US ruling class in the Greater Middle East, as has been brought home forcefully by the outcomes of its disastrous military interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan since 2001.11 Moreover, US power in the wider region has never relied exclusively on Israel’s “watchdog” role, instead requiring a range of local junior partners. However, how does this system of unequal partnerships between the US and its local allies actually work? It is worth emphasising that, as the Marxist theorist Tony Cliff wrote in 1945, imperialism is not best conceived as “a mechanical external frame” but instead as a set of processes “connected with every fibre of the body” of the economy and society of the dominated countries.12 When he wrote these words, Cliff was referring to the relations between the old colonial powers (Britain and France) and the colonised nations of the Middle East, but the general point still holds today. The relationship between the US, Israel and the other ruling classes of the region has been internalised by state institutions across multiple countries. It is felt through the presence or absence of experts, the circulation of their policy manuals and directives, the flows of aid and diplomatic exchanges. Most importantly it is woven into the fabric of the military and security apparatuses of these states. The type and quality of equipment soldiers carry, the training and career histories of important layers of officers, relations between military institutions and the rest of the state, and the role of the military in wider society are all to some extent its correlates.

It is tempting to note the archipelago of US bases across the Middle East, and track the career paths of the senior officers in the armies of US allies through US military academies, and conclude that very little has changed since the period of direct colonial rule. This would be a mistake. Crucially, the “internalisation” of imperialism within the states of the region since the anti-colonial revolutions has taken place alongside the emergence of local centres of capital accumulation and the rise of local capitalist classes. Military institutions have also for most of that period acted as direct agents of capital accumulation across large parts of the region, with military officers playing various roles as managers, owners and investors in capitalist enterprises. This is distinct from, but evidently complements, the classic role played by military institutions in capitalist states as indirect agents of capital accumulation, as mapped out by Friedrich Engels, Lenin and Karl Liebknecht during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.13 In this model of the role played by military institutions under capitalism, the leadership of the armed forces are part of the wider ruling class and form the coercive core of the capitalist state. Their primary role is as guarantors of the necessary conditions for capital accumulation. “Indirect” here should not be taken as meaning subordinate or peripheral; in fact, as Lenin articulated clearly in his classic The State and Revolution, the capitalist state must be “smashed” for any social revolution from below to succeed precisely because it is a coercive apparatus created with the express purpose of ensuring the continued robbery of the direct producers.14 The military’s role as internal gendarme is the obverse of its equally important aspect as external predator in the interests of the bourgeoisie associated with its state. This propels it into conflicts with the other members of “the band of warring brothers” making up the global community of capitalist ruling classes.

The Israeli military’s role in both the formation of the state and its subsequent evolution has much in common with many of its regional neighbours. In general terms it fits the dominant pattern across the region of a highly militarised society and economy. The long-term militarisation of the economy in the region (or rather the extreme difficulty in untangling military and civilian components of the ruling class from each other) is the outcome of interactions between several different factors. The first of these was the general weakness of the indigenous bourgeoisie (largely a result of the stunting and distortion of its development by colonialism).15 Junior officers drawn from the middle class and even relatively poor backgrounds (sometimes from religious minorities, as was the case in Syria) often formed one of the most energetic and cohesive components of the modern middle class. This middle class substituted itself for the missing or weak indigenous bourgeoisie by seizing state power and ousting the political regimes allied with the colonial powers.16

A second factor driving the militarisation of the regional economy was the intense imperialist competition between the Global Powers in the area. This reflected its ongoing geostrategic importance and the centrality of oil and gas to the global economy by the mid-20th century.17 One facet of this competition was the development of a large military “footprint” throughout the region in the form of bases, military exercises, and the provision of training and advisors by the US and the Soviet Union to their junior partners. Another facet of this is the strong mutual interest of the global imperialist powers and the military sections of the emerging ruling classes of the region in the purchase and consumption of arms and other military technologies. Arms transfers to the Middle East functioned as a mechanism for the military-industrial complexes of the Great Powers to justify their own voracious appetites for resources and funding. Increasingly, the wars fought between Middle Eastern states consumed vast amounts of weapons, which required constant replenishment at source. This helps to explain why, as the economies of much of the region shifted from a state capitalist model to a more neoliberal one from the 1970s onwards, the social and political weight of the military as an institution was not reduced.

Israel fits the regional pattern of being both “an army with a state” and “an army with an economy”, with the added intensifying factor of the violent circumstances of the country’s birth. The military institutions of the Zionist movement were instrumental in creating the state through the ethnic cleansing of the majority of the Palestinian population.18 After the Nakba, their successors, the armed forces of the independent Israeli state, played a fundamental role in capturing military subsidies from the US. They then helped to incubate independent capital accumulation through the military industries and services that form the strategic core of the Israeli economy today. The Arab nationalist junior officers who captured states across the region during the 1950s and 1960s followed a more zigzag path—in most cases oscillating between the Cold War superpowers before their successors ended up becoming allies of the US. Nevertheless, the overall process is relatively similar. The Egyptian military, like its Israeli counterpart, also spent the neoliberal era attempting to incubate new industries (for instance, car manufacturing and electronics), seizing land in order to enrich the officer class through property speculation and entrench its power, and buying up former state assets at knockdown prices (for example, the Alexandria Shipyards, which were acquired by the Egyptian Ministry of Defence as part of a consortium that includes Gulf investors).19

Forged in the crucible of war: Israel’s high-tech economy

The rise of Israel’s information technology sector illustrates how the dynamics of imperialist competition worked their way into institutions and economic processes that have sustained the specific racist form of the Israeli state. Israeli government data shows that high-tech industries already accounted for 37 percent of industrial production in 1965. By 1985, this had risen to 58 percent, soaring again to 70 percent 2006. The 1990s saw rapid growth in high-tech exports, which quadrupled in volume from $3 billion in 1991 to $12.3 billion in 2000 before more than doubling again to $29 billion in 2006. In addition, some $5.9 billion of high-tech services were also exported.20 The resulting dominance of information technology in the service sector is also confirmed in Israeli trade statistics (see table 1).

Table 1: Selected Israel trade statistics, 1995-2019

|

|

1995 |

2000 |

2005 |

2010 |

2015 |

2019 |

|

Computer and communications services as percentage of commercial services exports |

36.5 |

57.7 |

60.2 |

63.4 |

73.5 |

78.4 |

|

Trade in services as percentage of GDP |

16.2 |

21 |

22.2 |

18.8 |

20.5 |

22.2 |

|

Export of goods and services as percentage of GDP |

27.5 |

35.6 |

40.8 |

34.8 |

31.6 |

29.3 |

Source: World Bank, WITS Data service.

The Israel ruling class promotes various myths and mystifications that cover over the real origins of its high-tech industries’ success. However, as Israeli government accounts emphasise, far from being the result of an “entrepreneurial” culture or the outcome of market forces, this spectacular development was the outcome of massive and sustained state investment. The primary reason why the Israeli state (unlike the white South African state during the same period) was able to find the capital and human resources to achieve this was intimately connected to the centrality of Israeli military capability in the architecture of US domination in Middle East.

The huge influx of immigrants from the former Soviet Union, which started in the late 1980s and continued through the 1990s, also played a significant role. This was the largest wave of migration to date under the “Law of Return”. This policy allows anyone with a Jewish parent, grandparent or spouse to immigrate to Israel and immediately claim Israeli nationality, regardless of whether their Jewish relative had immigrated themselves or was even still alive.21 By 2018, there were 1.2 million migrants from the former Soviet Union living in Israel, most of whom had arrived since 1990.22 The percentage of scientists, academics and other related professions among the former Soviet Union immigrant labour force in Israel was 69.4 percent as opposed to 26.9 percent for the Israeli Jewish labour force.23

Within two decades the economic gap between migrants from the former Soviet Union and the non-Orthodox Jewish Israeli population had narrowed dramatically, with the average wage of these migrants closely approaching the average for the Jewish working population.24 This contrasted strongly with the experience of Palestinian citizens of Israel, who largely remained trapped in poverty and facing systematic discrimination in access to education and more qualified, better-paid jobs.25 The huge investment by the US in the active maintenance of Israel’s Qualitative Military Edge over other military forces in the Middle East directed several feedback mechanisms specifically into the high-tech sector. One of these was the role of the Israeli military itself as both consumer and developer of information technology products and services. This was demanded by its dual missions: maintaining the apartheid system that governs the lives of Palestinians under Israeli occupation and protecting its position as a regional enforcer of the military and diplomatic interests of its imperial patron, the US. Indeed, the Israeli military has enjoyed high levels of collaborative access to the research and development component of the US military-industrial-services complex, unlike other purchasers of its arms and military technologies. This includes first regional access to US military technology and options to customise its weapons systems.

The Israeli military is not just a consumer and adapter of US weapons. Israeli military products and services also flow back in the opposite direction, including the Iron Dome missile defence system and the Trophy active protection system for armoured vehicles.26 A recent article in the US journal Joint Force Quarterly praises the long-term strategies adopted by the Israeli military and academic establishments to create a cadre of technologically proficient officers through offering intensive education in STEM (science, technology, engineering and maths) subjects as part of military service, building in close linkages with the “private” technology sector. The Talpiot programme, which was launched in 1979 and recruits high school graduates for a nine year stint in military service combined with advanced STEM training, “is perceived as a breeding ground for Israel’s tech industry CEOs”.27 More than a third of the world’s cybersecurity “unicorns” (private companies valued at over $1 billion) are Israeli, and in the first six months of 2021 Israeli cybersecurity companies raised 41 percent of the total global funds raised by firms in the sector worldwide, according to the Israel’s National Cyber Directorate.28

The relationship between Palestinian dispossession and the cybersecurity sector in Israel is well illustrated by the Gav-Yam technology park in Beersheba, which focuses on cybersecurity. Tenants include major international and Israeli computing and military companies (including Deutsche Telekom, IBM, Oracle, Lockheed Martin, EMC and PayPal) whose offices are located in close proximity to Ben Gurion University’s Cyber Security Research Centre and the Israeli military’s “ICT campus”.29 The “technology park” is a joint venture between the university, the private sector and the government. It is located in the heart of al-Naqab desert region (known in Hebrew as the “Negev”), where forced demolitions of Palestinian villages and homes are intensifying.30

The process of mutual reinforcement between the Zionist settler colonial project and Israel’s militarised economy thus operates at multiple levels of state, society and economy across historic Palestine and beyond. Palestinians, including the Arab minority that remained within the borders of the new Israeli state, have been systematically excluded from the most strategically important centres of capital accumulation in the military industries and services. Historically, these sectors were tightly bound up with the military establishment and compulsory military service for Jewish citizens, and Palestinians have been shut out of them for reasons of “national security”. Indeed, the combat doctrines, management techniques and technologies that underpin Israeli military power in the region have been more frequently tested on Palestinians than anyone else.

Towards a “Unity Intifada”?

Processes of capital accumulation drove the endless wars and continued waves of colonisation that shattered the class structure of Palestinian society after the Nakba. However, over time, these same processes began to reconstitute a social basis for the rebirth of resistance both in exile and under occupation. From the mass nationalist movement rooted in Lebanese and Jordanian refugee camps in the 1960s and 1970s to the First Intifada of 1987 and the 2021 general strike, all the major waves of the Palestinian struggle have been driven by the interaction between social injustice and national oppression. At their heart, these have been risings of the working class and poor, who form the majority of the Palestinian population, against the racist system that impoverishes and represses them. Nevertheless, the weight of historical evidence strongly indicates that, in order to rupture the Israeli state’s control over their lives, Palestinian resistance must reach beyond the borders of historic Palestine. Its success depends on becoming more deeply integrated into the revolutionary struggles of workers and the poor against the states of the wider region.

The re-establishment of Palestinian unity through collective action from below during the historic general strike across Palestine in May 2021 strongly suggests that pressures are building up towards the eruption of a new major cycle of resistance. Although it is always risky to predict the future scale of mass movements before they arise, it does seem likely further storms are on the way. Palestinian activist Riya al-Sanah notes that, though the general strike was officially called by the High Follow-up Committee for Arab Citizens of Israel—a body composed of the traditional political leaders of Palestinian citizens of Israel—the mobilisation that ensured its success came from below. “The High Follow-up Committee…often calls for strikes, but these are strikes for the Palestinian community in Israel only”, she points out. “Usually, nothing happens on those days: no politics in the streets, no mobilising”.31 This time, despite only a couple of days of preparation, the situation was very different. Hundreds of thousands of Palestinians stopped work and joined political marches and rallies. The mobilisation extended from Yafa, Haifa and Umm al-Fahm within the borders of Israel to Hebron, Jenin and Ramallah in the West Bank.32

Across historic Palestine, protesters raised the same demands: stop the bombardment and siege of Gaza, halt the ethnic cleansing of Palestinian families from East Jerusalem, and end the violence and incitement against Palestinians by Zionist settler movements. This alignment of demands and protest tactics represented the temporary fusion of a whole range of localised campaigns challenging the Israeli authorities and the apartheid system. These included escalating (and partially successful) mobilisations by Palestinian residents of East Jerusalem to defend their presence in public spaces such as the Damascus Gate and their right to worship at the Al-Aqsa mosque. More generally, East Jerusalemites have launched campaigns to defend their homes from eviction orders in neighbourhoods such as Sheikh Jarrah and resist racist harassment by militant settler groups.33 These activities build on several years of action among young Palestinians, who have tested themselves against the authorities in street protests and campaigning. Networks of youth activists have worked alongside the long-standing Popular Committees, which typically bring together activists from different political currents within a local neighbourhood. According to Akram Salhab and Dahoud al-Ghoul, these were “huge civic uprisings involving sustained protest by tens of thousands. This civic spirit and infrastructure are the basis upon which the more recent uprising was launched”.34

The sense of confidence this has imbued in Jerusalem’s Palestinian youth is palpable not just at the political level but also in the music and culture of the streets. This is permeated with an “up yours” attitude to those in power, often summed up with the term “khawa”, which loosely translates as “despite your best efforts”:

In Jerusalem, khawa is a way of life. Palestinians continued their demonstrations in Jerusalem khawa, undeterred by the machinery of oppression or the closure of the entrances to Sheikh Jarrah. They spoiled the Zionist celebration of Jerusalem Day, which marks the “reunification” of the city, and khawa they forced the cancellation of the march in the Old City. They barricaded themselves inside the Al-Aqsa mosque and stood up to bullets and tear gas khawa.35

Among the Palestinian citizens of Israel similar processes have been taking place as a result of increasing political repression and ongoing economic marginalisation. Two factors in particular have intensified the pressures on their daily lives in recent years. First, the passing of the Nation State Law of 2018 made explicit the unequal status of Palestinian citizens of Israel compared to Jewish citizens. In truth, this symbolic change merely gave legal form to a lived reality of decades-long oppression, but it has also further boosted the idea of joint action with Palestinians elsewhere to confront a single apartheid system. Second, Palestinians citizens of Israel have faced increased harassment and violence from settler movements in the last few years. Palestinians in the West Bank have long endured racist attacks from armed settlers, who destroy their crops and vandalise their property. However, more recently, far-right Jewish supremacist movements have grown in size and confidence, and now they are targeting Palestinians in cities within the 1948 borders of Israel such as Haifa, Lydd and Yafa. There were many reports of settler groups on Telegram and WhatsApp mobilising armed mobs to attack Palestinian homes and businesses in May 2021.36 In Lydd, armed settlers patrolled the streets with the Israeli police while the city was placed under a military curfew.37 As in Jerusalem, new structures of community mobilisation and self-defence are starting to form in order to resist these outrages. Al-Sanah explains:

We found ourselves in a place where we had to self-organise and discovered that we can actually do it. Local committees developed—local groups and autonomous kinds of political organising away from established structures… In Haifa, for instance, we had a neighbourhood defence committee, a legal support committee, a medical care committee and a mental health care committee. There were various forms of local, independent and collective committees that were working as part of this uprising, and Haifa wasn’t the only case where these things happened.38

The predominantly Palestinian towns in the north of Israel, such as Umm al-Fahm, have also been the site of massive popular campaigns over the past few years. Much of this action has centred around a wave of violent crime that has led to hundreds of Palestinians being murdered. Thousands took to the streets of Umm al-Fahm for ten consecutive weeks in February and March 2021. Palestinian activists link the crime wave directly to the establishment of Israeli police stations in the area after the repression of protests in 2000, arguing that the Israeli police tolerate and even encourage the activities of criminal gangs as a way of undermining political resistance. Just as among black people in the US who face a devastating combination of police brutality and violent crime, the primary demand of these Palestinians is not to strengthen the police but to defund and remove them.39

Meanwhile, a space has opened for new movements in the West Bank because of the accelerating decay of the mainstream nationalist movement Fatah, which has dominated the Palestinian Authority since its creation. These new movements have emerged in response to a range of questions. Despite difficult conditions, there is still a culture of protest, collective action and self-organisation seeking to confront Israeli settlers and state forces and defend Palestinian political prisoners. Other activists have raised issues such as sexual harassment and violence against women, which sparked a rash of demonstrations led mainly by young Palestinian women in September 2019. These developments have led to the creation of new organisations such as Tal’at (“stepping out”), a recently founded Palestinian feminist movement. The rampant corruption of Fatah’s leadership has also been a source of unrest, with criticism coming even from some of its former members. The murder of one such critic, Nizar Banat, by Palestinian Authority security forces ignited several days of large protests in June 2021.40 Banat had been planning to stand in the Palestinian Authority legislative elections scheduled for May 2021, before they were postponed by the head of the Palestinian Authority, President Mahmoud Abbas.

Fatah’s gerontocratic leadership is now facing multiple challenges. Fatah activist Marwan Barghouti, currently a political prisoner in Israel, reportedly refused to stand down from his plans to contest the presidential election. At the same time, Islamist movement Hamas looked set to win a sweeping victory in the legislature according to opinion polls.41 Hamas’s standing has been boosted by its refusal to surrender to Israeli military pressure, answering the Israeli security forces’ repression of worshippers at the Al-Aqsa mosque with rocket fire across the borders of the Gaza Strip.

In the Palestinian context, international visibility and connections with the large, politically active diaspora are important, as is support from the international solidarity movement. This movement is increasingly organising around the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions call from Palestinian civil society and trade unions, which is removed from the older nationalist currents and not dominated by Palestinian Authority loyalists. Social media has been a crucial tool for some younger activists such as Mona and Mohammed al-Kurd, who used Twitter to amplify long-standing struggles in Sheikh Jarrah. Their message reached broad international audiences, including solidarity movement activists, policy makers, major liberal NGOs and the international media.

As Ilan Pappé noted in this journal in January 2021, these developments do not mean that all the existing political currents such as Fatah are fading into obscurity.42 Moreover, the structure of Israeli apartheid constantly drives the movement from below into a nationalist framework. This gives historic nationalist currents constant opportunities to reinvent themselves, at least as long as they continue to relate to popular resistance.

A “political strike with economic implications”

Despite the survival of established political forces, signs are pointing towards the opening of a new phase in the struggle across historic Palestine. This is characterised by the emergence of a new generation of activists and the fragmentation of older political currents. If this combination of rebellious youth, an expanding culture of protest and the fragmentation of old political authorities sounds familiar, it is because this pattern has been repeated in several major cycles of popular uprisings across the region (and beyond) since the end of the 1970s.

However, the lessons from the revolutionary waves of 2011-2 and 2019-21 in the Middle East and North Africa are that a “civic uprising” requires more than numbers on the streets to achieve its goals. We need to pay close attention to the social aspect of the Palestinian rebellion, asking whether it can mobilise forces with sufficient social weight to disrupt, paralyse and ultimately break down the Israeli state’s repressive machinery. Riya al-Sanah describes the 2021 general strike as “a political strike that had economic implications”.43 These implications were significant in some areas of the Israeli economy but less so in others. The Israeli construction sector was hit particularly hard, according to Israeli newspaper Ha’aretz:

In Beit Shemesh, which is experiencing a construction boom, all the cranes were silent. One crane operator said that many operators are Arabs who were striking, adding, “If we would all fight that way for workers’ rights maybe we would achieve something”.44

Of 65,000 Palestinian workers who cross the “green line” into Israel daily in order to work on construction sites, only 150 showed up on the strike day, causing losses of $40 million. Nearly 1,000 Palestinian bus drivers working for Israeli companies took strike action, around 10 percent of the total labour force.45 Other groups of Palestinian workers, such as pharmacists and workers in the Israeli health sector, were reported to have been less confident about joining the strike.46

Writer Andrew Ross notes that the 2021 general strike continued a tradition of strikes from the First and Second Intifadas. The withdrawal of labour often takes place within a broader tactical repertoire of shutting shops and businesses, refusing to pay tax, and boycotting Israeli goods.47 Of course, the strategy of calling for political strikes and mass participation of workers and the poor as part of a national liberation struggle has an even longer history in Palestine and the wider Middle East. It was also a cornerstone of the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa, which developed the tactic of mobilising for “stay-aways” through a combination of workplace and community organising.

However, the experience of other popular uprisings—including the fight against South African apartheid—does not just underline the need to revitalise Palestinian workers’ self-organisation as workers rather than just as working-class participants in a revived Palestinian national liberation movement (important though that is). It also points to the urgency of mobilising the working class beyond the borders of historic Palestine to challenge the role of their “own” states in propping up Israeli apartheid through alliances with the US.

As the capitalist system has matured, it has become rarer for mass popular movements to force a meaningful shift towards forms of democracy that make a difference to ordinary people’s lives. Such transitions would not mean the development of elite forms of electoral competition over government posts and the allocation of resources. Instead, they would mean workers and the poor winning the ability to organise, debate and mobilise in public spaces, workplaces and neighbourhoods in order to push back against exploitation and oppression. Yet, much more common than this have been revolutionary eruptions that merely force a temporary democratic opening—or at least prove that one is possible.

A key common element in most, longer-term democratic transitions, and even in the more fleeting democratic openings, is the central role played by organised workers and workplace struggles. On a global scale, we could point to the role of workers in the 1974-5 Portuguese Revolution, the South Korean struggle for democracy between 1980 and 1988, the campaign to topple the military dictatorship in Brazil in the 1980s, and the fight against South African apartheid. Within the Middle East, the most enduring democratic opening from the 2010-12 round of uprisings was in Tunisia, the country with the largest and most politically influential workers’ movement.48 The most catastrophic outcomes on a societal scale were to be found in the countries where organised workers were largely absent as a social, let alone political, force—Syria, Libya and Yemen. In contrast, the workers’ movement was capable of shaping the early trajectory of the Egyptian Revolution through the social weight of its collective action. However, it was unable to escape the constraints of its political marginalisation, leading to the abortion of the revolutionary process.

What has this got to do the future of the Palestinian national movement? The weight of this complex historical experience suggests that major social struggles by organised workers for the cause of Palestinian liberation are going to be necessary to even begin to dislodge the grip of the militarised, authoritarian political system adopted by the Israeli ruling class. The experience of Palestinian history also points in the same direction. When the First Intifada erupted in 1987, it followed nearly two decades of growing trade union organisation. This was shaped by the social questions thrown up by dramatic shifts in the structure of the Palestinian working class, which resulted from the Israeli economic strategy of using the Occupied Territories as a dormitory for “migrant” Palestinian labour after 1967.49

By 1987, there were 130 unions in the West Bank. Mostly were relatively small and had less than 250 members, although others—such as the Construction and General Institutions Workers’ Union in Ramallah and the Hotel, Restaurant and Café Workers Union in Jerusalem—averaged 1,000 dues paying members.50 Unions did not focus solely on workplace issues in a narrow sense but developed a dense mesh of organisations supporting their members in a wide range of areas. These included medical, health, insurance and savings services, social and cultural activities, voluntary work, sports activities and committees to run their financial affairs. Most of these structures were elected and, at least in theory, there were democratic mechanisms that allowed activists at the base of the union movement to shape the decisions through election of delegates from local to national leadership positions.51

Unions representing Palestinians working in Israel were (and still are) prevented from direct engagement and negotiation with Israeli employers by the occupation’s legal structures, which banned Palestinians from organising their unions “inside” the State of Israel. There was also pressure on Palestinian unions that organised workers employed by Palestinian businesses to moderate or suspend the class struggle in order to maximise national unity.

Competition between the Communist Party and the major nationalist currents (particularly Fatah, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine and the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine) over the reviving workers’ movement intensified during the late 1970s. In the early 1980s, this competition led to splits within the trade union along factional lines and in some cases to the proliferation of duplicate, factionally-aligned unions that represented the same groups of workers.52

The reason that the Intifada was sustained beyond the first explosion of rage in December 1987 lay in the organisational structures that powered protests at a popular level: a network of “popular committees” (“lijan sha’abiyya” in Arabic), underground trade unions and community organisations. Many of these existed prior to the Intifada, or at least the groundwork had been laid in the years before the uprising through local struggles, which acted as rehearsals for the mass confrontation in 1987-8. The scope of these popular organisations went far beyond the coordination and mobilisation of protests, instead encompassing building alternative Palestinian services in areas such as education and health. The efforts by Palestinian teachers to deliver alternative education during Israeli-imposed school closures provides a good example of this. As educator and activist Yamila Hussein notes, the Israeli authorities effectively criminalised education for Palestinian children during the Intifada. Security forces harassed and arrested students and teachers “for participating in ‘underground’ classes or even for carrying books”.53 In response, Palestinians developed “popular teaching” that radically challenged the Israeli-censored school curriculum and connected education to resistance.54 The Intifada was also sustained by medical relief committees, healthcare and social work organisations, and community conflict resolution services. In addition, the popular committees, primarily focused on political work, had emerged in nearly every village, refugee camp and neighbourhood across the Occupied Territories by early 1988.55

Unfortunately, the period of the Oslo Accords during the 1990s, which led to the creation of the Palestinian Authority, saw the retreat of both grassroots union organising and neighbourhood-based mobilisational networks. The energy of a layer of activists in the mainstream nationalist organisations, particularly Fatah, was drawn into building the structures of the Palestinian Authority, which many hoped would be a step towards an independent Palestinian state. In reality, the Oslo Accords were a trap: the Israeli settlements expanded, and what Jeff Halper has called Israel’s “matrix of control” over Palestinian land, water resources and population centres tightened.56

The major nationalist factions have traditionally called on workers to refrain from fighting for their rights against Palestinian-owned businesses and challenging the Palestinian Authority, arguing that the struggle for national liberation was paramount. There are signs that this “freezing” of the class struggle has begun to thaw, including strikes among taxi drivers in 2012 and teachers in 2016 and 2020.57 The 2016 action involved nearly 35,000 teachers, who organised the largest teachers’ strike in Palestinian history despite their union leadership acting “more as a mediator for the Palestinian Authority than an advocate for union members”.58

Nonetheless, the way in which the apartheid system functions, for all the reasons outlined previously, creates structural obstacles to the realisation of Palestinian workers’ class power in the areas dominated by Israel. The Palestinian public sector is reliant on a combination of international aid and funding from Israel. At the same time, Israeli road blocks and the seizure of land and water resources by settlers have destroyed or badly damaged much of Palestinian agriculture and industry. This process of “de-development” has weakened the strategic power of the Palestinian working class.59

The same apartheid structures have politically neutralised the economic struggles of Jewish Israeli workers. Strikes and even large-scale social protest movements, such as the wave of huge “social justice” demonstrations over declining working-class and middle-class living standards in 2011, have not been able to break through the confines of Zionist ideology to show solidarity with Palestinians. Indeed, Israel’s historic trade unions have been part of the settler-colonial enterprise for longer that the Israeli state. During the period of British mandatory rule, the General Organisation of Workers in Israel, or “Histadrut”, was a pioneer of the racist “Jewish labour” policy of excluding Palestinian workers from the economy. It founded the paramilitary Haganah (literally, “the defence”), one of the Zionist militias that played a pivotal role in the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians during the Nakba.60 For decades this “union federation” was also a major employer and state institution. The Histadrut collected millions of pounds in compulsory wage deductions for health insurance and social protection from Palestinian workers who it refused to represent. It also refused to transfer these funds to Palestinian unions in the West Bank as had been agreed under the Oslo Accords.

The Histadrut’s membership collapsed in the mid-1990s after healthcare reforms broke the link between union membership and access to health insurance in Israel. However, it has not been replaced by more progressive alternatives. After the shrunken Histadrut, which now represents around 700,000 members, the second largest union federation is the Histadrut Leumit (“National Histadrut”), which is affiliated to the hard-right Likud party and has 100,000 members. This is followed by the more left-wing Koach LaOvdim (“Power to the Workers”), which only counted 13,000 members as of 2018 (although it claims to represent around 35,000 workers through collective bargaining agreements).61 Koach LaOvdim and the 2,300-strong Workers’ Advice Centre-Ma’an union do recruit Palestinians, but as writers Sumaya Awad and Daphna Thier point out, neither have shifted their Jewish members away from Zionism. The enmeshing of trade unionism with settler colonialism means that:

Unions in Israel are pulled rightward by their Jewish members. In order to recruit, they must set aside the question of the occupation. Otherwise, they doom themselves to marginality. This is the nature of labour in an apartheid economy. Almost complete separation means that, by design, Jews and Palestinians rarely work alongside one another as colleagues. Instead, they are segregated, entrenching racism and ensuring that national loyalty trumps class consciousness.62

Palestine and revolution in the region

Across historic Palestine—as elsewhere around the world—there is a working class majority that shares a common fate of exploitation but is divided by its experiences of oppression. At the moment, the grip of apartheid-justifying racism within the Jewish Israeli part of that working class seems unshakeable. The reproduction of racist ideas is stuck in a self-perpetuating cycle, not because the ideas themselves are all-powerful but because the material and social processes that give rise to them continue to dominate the political economy of historic Palestine. These include the capture of massive subsidies from the US state for the settler-colonial state-building project by the Israeli ruling class, the dependence of the economy on a military-industrial-services complex that is parasitic on its far larger counterpart in the US and the societal impact of huge waves of Jewish settlement.

Human Rights Watch reports that the Palestinian and Jewish populations each stand at around 6.8 million.63 The approximate parity in numbers between Jewish Israelis and Palestinians within the borders of historic Palestine presents a political challenge to the Palestinian national movement. It is very unlikely that the current Israeli state can be defeated militarily by the Palestinians, even if acting in concert with neighbouring states. Moreover, conditions of war simply intensify the attachment of working-class Jewish Israelis to “their” state and “their” army, particularly if they fear defeat would pose a direct threat to their existence. This is why the goal of creating one, democratic, secular state in Palestine with equal citizenship for all is an important counter-argument to Zionist claims that only an exclusively Jewish state can protect Jewish Israelis.

The depth and scale of change required to create a genuinely democratic state in Palestine demonstrates the kinship between the struggle there and those in the wider region. Undoing the militarised structures of Israeli apartheid is no less of a challenge than overcoming the other authoritarian regimes that surround historic Palestine. A major ground for hope that both are possible lies in the history of mutual reinforcement between the revolutionary struggles in Palestine and the wider Middle East over the decades. The defeat of previous waves of uprisings in Palestine and the wider region make clear that this process of interaction between revolutionary struggles cannot be left to chance. Instead, deeper rooted revolutionary organisation is needed both in Palestine and the surrounding countries.

The experience of the popular uprisings since 2011 illustrates these points. Tunisia led the way with mass strikes and protests, bringing down the dictator Ben Ali in January 2011, followed by the uprisings in Egypt, Syria, Bahrain, Libya and Yemen. Even Saudi Arabia could not escape the revolutionary tide; mass protests shook its Eastern Province, which is close to Bahrain and has a largely Shia population. Popular protests mobilising the urban poor, the organised working class and significant sections of the middle class unleashed a regional revolutionary process. These events threatened to fracture the regimes forming the weaker links in the architecture of imperialism. Dictators tottered in country after country, and they fell from power in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya and Yemen.

Throughout these events, popular forms of organised solidarity with the Palestinian struggle remained a phenomenon across the region, emerging as a significant factor at certain points in these revolutionary processes. This proved that solidarity with the Palestinian cause had survived both the decay of the Arab nationalist and Stalinist left, which had compromised themselves through their proximity to state power during the 1970s and 1980s, and the betrayals of the Palestinian national leadership during the “peace process”. Indeed, solidarity with Palestine was a persistent feature of a rising “culture of protest” during the pre-revolutionary period in many cases, particularly in Egypt and Tunisia.

The Palestinian cause could potentially act as a bridge between activists in the orbit of the Arab nationalist, Islamist, liberal and left-wing currents of the opposition political spectrum. Even if formal coordination and joint activities between Islamists and the other political tedencies were relatively rare, popular solidarity with Palestine often formed a point of consensus among otherwise fractured opposition movements. Palestine repeatedly demonstrated its capacity to spark mass collective action in ways that few other regional causes could. These solidarity movements often continued to expand and deepen during the revolutionary crisis itself. In Egypt, for example, mobilisations explicitly in solidarity with the Palestinian struggle expanded from protests in Tahrir Square on Nakba Day in May 2011 to a major confrontation between protesters and the security forces later that year. In September 2011, Israel’s ambassador fled Cairo after protesters besieged the embassy. The Israeli military assault on Gaza in November 2012 took place in a changed political context, with the Islamist Muslim Brotherhood in office after victory in the parliamentary and presidential elections. Egyptian activists mobilised solidarity convoys bringing aid to the besieged Gaza Strip, and even the Egyptian prime minister, Hisham Qandil, put in a brief appearance in Gaza alongside Hamas leaders as Israeli missiles rained down.64

However, the forward momentum of the Egyptian Revolution was halted and turned back on itself as the counter-revolution took hold. This was the result of two main factors. First, reformist Islamist political forces gained partial access to the state apparatus through elections held after the revolution, but they explicitly refused to challenge either the military’s role in the state or the military’s relationship with Israel and the US. Any deviation from the script—“peace” with Israel—would have made it extremely difficult to access international aid and investment. The Muslim Brotherhood’s leadership also hoped to negotiate its way into sharing power with the leadership of the armed forces. Notably, this involved President Mohamed Morsi, who was elected in 2012 on a Muslim Brotherhood ticket, appointing the man who would later overthrow him, Field Marshal Abdelfattah al-Sisi, as Minister of Defence.

Second, the revolutionary movement’s mobilisation of mass protests in the streets and strikes in the workplaces failed to form a counterweight strong enough to push the reformists towards challenging military control of the state. Given this, the reformist Islamists were unwilling to turn their rhetoric of Palestinian solidarity into actual withdrawal from the peace treaty with Israel, despite long-standing commitments to do so. There is little doubt that a popular mobilisation during 2011 or 2o12 for the cancellation of the 1978 Camp David Accords between Israel and Egypt would have generated a major political crisis. Such a movement would have focused attention on the role of the Egyptian military as guarantors and enforcers of the interests of the US and its ally Israel. Instead, the Islamist movement was subsumed by desire to negotiate its way into the corridors of power without disturbing the existing political system.

Meanwhile, the uprisings emerging in 2010 and 2011 elsewhere in the region became bogged down in civil wars as the old regimes fought back militarily, often sucking global and regional imperialist powers to the conflict. Only in Tunisia did the mass movement appear to have forced a genuine programme of political reform on the state apparatus. A crucial underlying reason for the derailment of the revolutionary processes in Syria, Libya and Yemen was the absence of an organised workers’ movement as part of the coalition of social and political forces contesting the old regimes. In Bahrain, trade unions did play an important role in the March 2011 uprising, but this was defeated by an external military intervention from neighbouring Saudi Arabia.

One further factor in the revolutionary context was the abeyance of the popular movement within Palestine. This followed the decline of the Second Intifada, which had erupted in September 2000 when the right-wing Israeli politician Ariel Sharon went to the Al-Aqsa mosque with an escort of 1,000 police officers. Protests were met with brutal repression once again, and nearly 500 were killed in the first few weeks of the uprising.65 In contrast to the First Intifada, Palestinian resistance this time took a more militarised form, and armed groups carried out a wave of suicide bombings that killed hundreds of Israeli civilians. Hamas was one of the leading proponents of this strategy, which sought to redress asymmetries of power between the Palestinians and Israel. It was hoped that this could create a more favourable context for negotiations, following the failure of the “peace process” to secure a viable Palestinian state.66 Nevertheless, the Second Intifada failed to reverse the setbacks of the previous decade. Israeli military control of historic Palestine remained intact. Right-wing Israeli governments, bolstered by popular support for their racist and repressive policies, accelerated the seizure of Palestinian land by settlers and promised “separation” between the two communities through the construction of huge walls and barriers. These defeats deepened fractures within the leadership of the Palestinian movement, and two rival Palestinian administrations emerged in the West Bank and Gaza, respectively dominated by Fatah and Hamas.

The case for revolution against Israeli apartheid

There is a tendency towards an unstable equilibrium between the Israeli ruling class and Palestinian resistance in the long term. The roots of both Israeli domination and Palestinian resistance in the political economy of historic Palestine are continually nourished by the large-scale social processes I have outlined above. This does not mean that the Palestinian movement can never be defeated or that Palestinian nationalism is an invincible force that will never disappear. Nevertheless, as long as the resistance has a social dimension rooted in the struggles of the poor against oppression, injustice and exploitation, there remains a mass base from which it can refresh and renew itself.

If a new cycle of mass struggle opens, what choices should activists in Palestine and the wider region make to try and avoid the fate of previous generations? This article has put forward an analysis that makes the case for developing a revolutionary strategy: embedding Palestinian liberation in the struggle to build revolutionary movements in the wider region, organically connected with the power of the working class. There are two important reasons for this strategic orientation. The first reason is that Israeli apartheid is functional to and reproduced by the dynamics of imperialism at a regional level. Moreover, its survival is not an anachronism—it is not some left over “unfinished business” from the colonial period. Instead, it reflects the continued exceptional importance of the Greater Middle East to the global imperialist powers.

The second reason is that the continual renewal of Palestinian resistance is a specific instance of the social and political processes that lead to repeated waves of revolutionary crises and popular uprisings in the Middle East. Unfortunately, the dominant political framework for the Palestinian struggle centres on seeking an independent state. However, this does not change the social character of the Palestinian mass movement. Although its leaders have generally been drawn from the middle class or the exiled Palestinian bourgeoisie, this movement remains deeply connected with the struggles of the poor and working-class majority of Palestinians, both under occupation and in the diaspora. Palestinian resistance remains an example to popular movements around the region both because ordinary people can see their own struggles mirrored there and because the same regimes that oppress them work directly with the US and its allies.

This article has also attempted to reverse the mirror by viewing the Israeli state not through the lens of its own false self-image as a “democratic exception” but as just another instance of an “army-with-a-state”. It is cut from the same cloth as the other highly militarised authoritarian regimes surrounding it, even if it is more successful in capturing subsidies from the chief imperial power to underwrite its industries and tool up its police forces. A sober assessment of the Israeli state views it as the single, authoritarian machinery that rules Palestine from the river to the sea. One result of this analysis is that expecting such a state to voluntarily give up on part of its territory, allowing a viable and sovereign Palestinian state to emerge beside it, is naive. This is particularly so because the world’s biggest imperialist power has poured money and arms into the Israeli state for over half a century.

Another challenge is that the Palestinian struggle has historically been unable to overcome the objective limitations imposed by the Zionist strategy of excluding Palestinian workers from the strategic core of the Israeli economy. This means that the Palestinian movement inevitably finds it difficult to exercise the kind of strategic power that organised workers usually possess in a revolutionary confrontation with the ruling class. Combined with the fragmentation and dispersal of millions of Palestinians around the region, it means that if the Palestinian struggle is confined to the interior of historical Palestine, it cannot rely on sheer power of numbers in a struggle with the apartheid state.

Thus the task of working out how to embed the Palestinian cause in the process of building revolutionary movements in the wider region is an urgent one. Developing a strategy that answers this question does not need to start from zero. It can draw on the experience of previous waves of struggle: the fights waged by the first generation of Palestinian revolutionaries after the Nakba, the uprisings at the end of the 1980s (including the First Intifada in 1987), and the waves of revolutions around the region since 2011. Based on those experiences, there are two key ways in which the question of Palestinian liberation is likely to be internalised by revolutionary movements in other countries in the region. The first of these is specific to countries with substantial Palestinian refugee communities such as Lebanon and Jordan. In these cases, as the rebirth of the Palestinian national movement in the 1960s showed, it is possible for the Palestinian struggle to interact with the class struggle, paving the way for a crisis and confrontation with the state.

The second way has historically been for the mobilisations in solidarity with the Palestinians to act as an accelerant to the local class struggle in countries without substantial Palestinian refugee populations. This happens by setting in motion (or deepening) a dynamic that Rosa Luxemburg called the “reciprocal action” between the political and economic aspects of mobilisations from below. The prehistories of the Tunisian and Egyptian Revolutions demonstrate how important the question of solidarity with Palestine can be on the streets and in the workplaces. On the streets, mobilisations for Palestine helped to knit together a “culture of protest”. In the workplaces, Palestine solidarity was one of the few issues that brought “politics” to workers’ organising in the years before the revolutions that began in 2010 and 2011. Moreover, because the tripartite alliance between the US, Israel and other regional militaries is deeply embedded in a large number of local states, solidarity with the Palestinian resistance can be a building block of popular mobilisations against military authorities.

The many diverse forms of struggle in Palestine and the wider region over the last half a century show that lacking an effective strategy to confront, challenge and ultimately break the military institutions at the heart of the state will lead to disaster. During the first wave of Palestinian revolutionary organising at the beginning of the 1970s, the nationalist leadership of the Palestine Liberation Organisation backed off from confrontation with the Jordanian monarchy during “Black September” and was unable to prevent the slide into civil war in Lebanon. During the second wave, peaking in the First Intifada of 1987, the same Palestinian leadership worked alongside Middle Eastern regimes threatened by popular mobilisations for political and social change in order to halt the feedback loop driven by solidarity with the Palestinian struggle. During the revolutions after 2010, popular Palestine solidarity movements ran up against the limits imposed by the political domination of reformist forces bent on compromise with the military at any cost and the preservation of the integrity of the state.

It might nowadays be asked, after the inferno of the counter-revolutions and wars that engulfed Egypt, Syria, Libya and Yemen, is there really any point talking about prospects for a return of revolution in the Middle East and North Africa? Our response should be another question: is there any real choice other than to organise and prepare for such an eventuality? All of the countries where mass popular movements arose in 2019-20 have past traumas on a comparable scale to the defeats of the 2011-2 wave: civil war in Lebanon and Algeria, sanctions, war and occupation in Iraq, multiple wars and genocide in Sudan. Jordan, which is home to a majority Palestinian population, experienced neither revolution nor catastrophic defeat during the last cycle of protest.

Of course, the deep wounds of societal catastrophe in Syria will certainly take a long time to heal, heaping further miseries on the Palestinians resident there. The scars of counter-revolution in Egypt will also last for a long time but, unlike Syria, Egyptian society has not been pulverised by war. Despite the grip of the military, there are still sporadic strikes and protests. A bigger unknown is what kind of opposition movement will survive and re-emerge, and how strong the left will be within it. What is certain is that the current military regime has made sure that Palestine remains on the minds of almost everyone who opposes the dictatorship. The Egyptian activist and blogger Alaa Abd el-Fattah recounts how the whispered news of the 2021 general strike in historic Palestine and Hamas’s rocket attacks on Tel Aviv reached the ward in Tora prison complex, where he is detained. Songs and chants hailing Palestinian resistance echoed between the cells of the leftist, Islamist and nationalist activists.67

It is also clear that breaking out of the pattern of coasting the ups and downs of the cycles of popular protest demands an active commitment to building revolutionary socialist organisation. Such organisation must be rooted in the social power of the working class, and it must be capable of resisting the pull of reformist compromises and the lure of nationalism. In this way it can help to build mass movements in historic Palestine and the entire region that are able to break the existing states.

Anne Alexander is the co-author, with Mostafa Bassiouny, of Bread, Freedom, Social Justice: Workers and the Egyptian Revolution (Zed, 2014). She is a founder member of MENA Solidarity Network, the co-editor of Middle East Solidarity and a member of the University and College Union (UCU).

Notes

1 Thanks to Joseph Choonara, Richard Donnelly, Rob Ferguson, Tom Hickey, Sheila McGregor and John Rose for comments on the draft of this article. I use the term “historic Palestine” for the territory between the River Jordan and the Mediterranean Sea, which is currently divided between the State of Israel, the West Bank and Gaza.

2 Human Rights Watch, 2021.

3 B’Tselem, 2021.

4 The number of states that currently restrict citizenship on a similar basis is relatively small. There are a greater number of states where the constitution includes clauses restricting rights to hold political office (such as the presidency) to members of a particular religion (or specifying that this role can only be held by a man). Socialists obviously ought to oppose these oppressive and discriminatory practices. However, Israel’s denial of full membership of the national community to non-Jews in its Basic Laws is genuinely unusual. Most states now provide mechanisms for new members to join the national community unconstrained, at least in theory, by kinship, ethnicity and religious belief.

5 Callinicos, 1985, p31. The fact that the form of apartheid in Palestine is sustained by processes deep within the regional and global dynamics of imperialism does not mean that there is no possibility of ending it without overthrowing capitalism. A reformist compromise preserving a capitalist state is always a possible outcome, as was the case in South Africa. On this point, see Callinicos, 1990 and 1992.

6 The Nakba is the Arabic term for the process of ethnic cleansing that occurred during the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948. Massacres and destruction of villages by Zionist militias forced 850,000 Palestinians to become refugees.

7 Rodinson, 2014.

8 Rose, 1986.

9 Orr and Machover, 2002.

10 Alexander, 2018.

11 Callinicos, 2014; Alexander, 2015.

12 Cliff, 2001.

13 Engels, 1884; Lenin, 1917; Liebknecht, 1973.

14 Lenin, 1917.

15 Trotsky, 1930.

16 Cliff, 1990.

17 Angus, 2016.

18 Pappé, 2006.

19 Alexander and Bassiouny, 2014.

20 Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2013.

21 Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2013.

22 Jewish Virtual Library, 2018.

23 Sabella, 1993.

24 Lieberman, 2018; Swirski, Attias-Konor and Lieberman, 2020, p18.

25 Sultany, 2012.

26 Dougherty, 2020.

27 Dougherty, 2020.

28 Solomon, 2021.

29 Hirschauge, 2015.

30 Masarwa and Abu Sneineh, 2020.

31 Notes From Below, 2021.

32 Kingsley and Nazzal, 2021.

33 Salhab and al-Ghoul, 2021.

34 Salhab and al-Ghoul, 2021.

35 Hassan, 2021.

36 Maiberg, 2021.

37 Ziv, 2021; Notes From Below, 2021.

38 Notes From Below, 2021.

39 Alsaafin, 2021.

40 Abu Sneineh, 2021.

41 Abu Amer, 2021.

42 Pappé, 2021.

43 Notes From Below, 2021.

44 Yaron, 2021.

45 Yaron, 2021.

46 Kingsley and Nazzal, 2021.

47 Ross, 2021.

48 The longevity of Tunisia’s experiment in democracy relative to other countries in the region is no basis for uncritical support for the Union Générale Tunisienne du Travail (Tunisian General Labour Union; UGTT) union federation. The UGTT leadership also bear responsibility for undermining the revolutionary potential of the mass movement from below and paving the way for the partial restoration of an authoritarian presidential system.

49 Hiltermann, 1993, p64.

50 Hiltermann, 1993, p69.

51 Hiltermann, 1993, p70.

52 Hiltermann, 1993, p69.

53 Hussein, 2005, p17.

54 Hussein, 2005, p19.

55 Chenoweth and Stephan, 2012, p124.

56 Halper, 2014.

57 Beinin, 2021.

58 Abu Moghli and Qato, 2018.

59 Roy, 1987.

60 Pappé, 2006.

62 Awad and Thier, 2021.

63 Human Rights Watch, 2021.

64 Al Jazeera, 2012.

65 Some 487 Palestinians were killed by Israeli security forces between 29 September 2000 and 1 January 2001, of whom 124 were children. During the same period, 44 Israeli security personnel and 112 Israeli civilians were killed by Palestinians—see https://statistics.btselem.org

66 Matta and Rojas, 2016.

67 Abd el-Fattah, 2021.

References