A widely anticipated recession across the major economies had not taken hold by the time International Socialism went to press, but there was no doubt that the global economy was coming under intense strain.1

The post-Covid rebound in economic activity has long since passed. The World Bank has revised down its latest forecasts and now expects zero growth across the Eurozone in 2023, with the German economy already contracting. The United States is expected to fare little better, with anticipated growth of 0.5 percent. China saw its monthly industrial output fall sharply in April. Its property market, which has played an outsized role in driving growth since the 2008-9 crisis, has slowed. Youth unemployment in urban areas has risen to one in five, twice its pre-pandemic rate.2 The stunning Chinese growth of the 1990s and early 2000s now seems a world away.

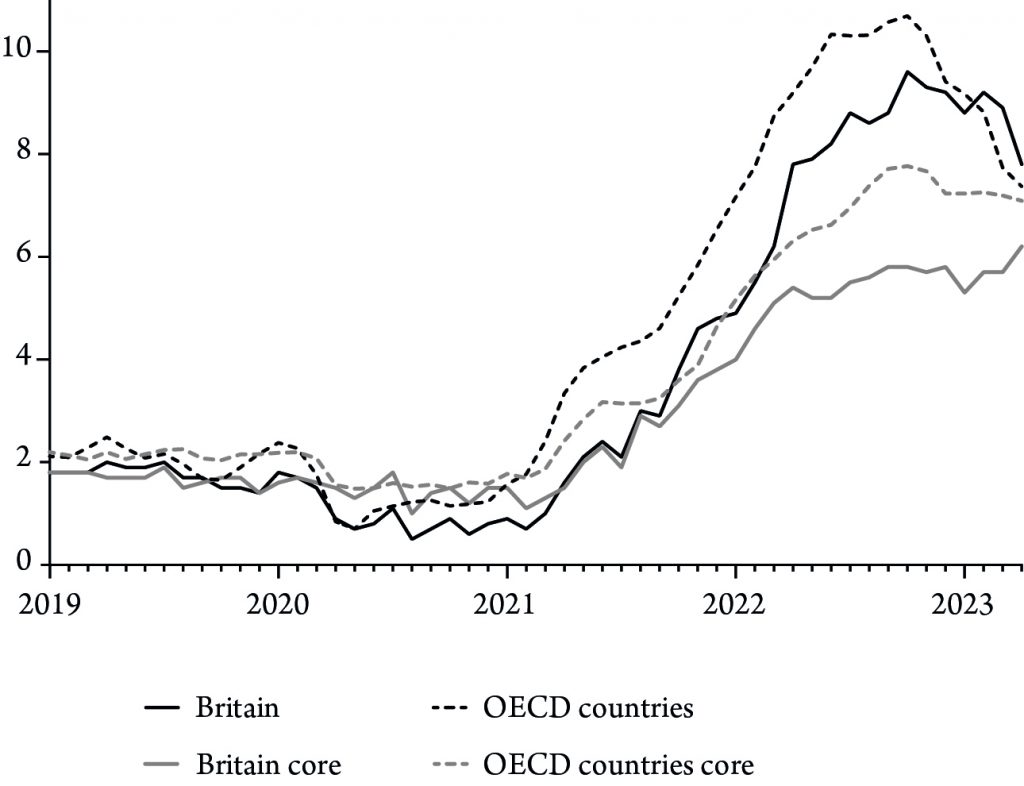

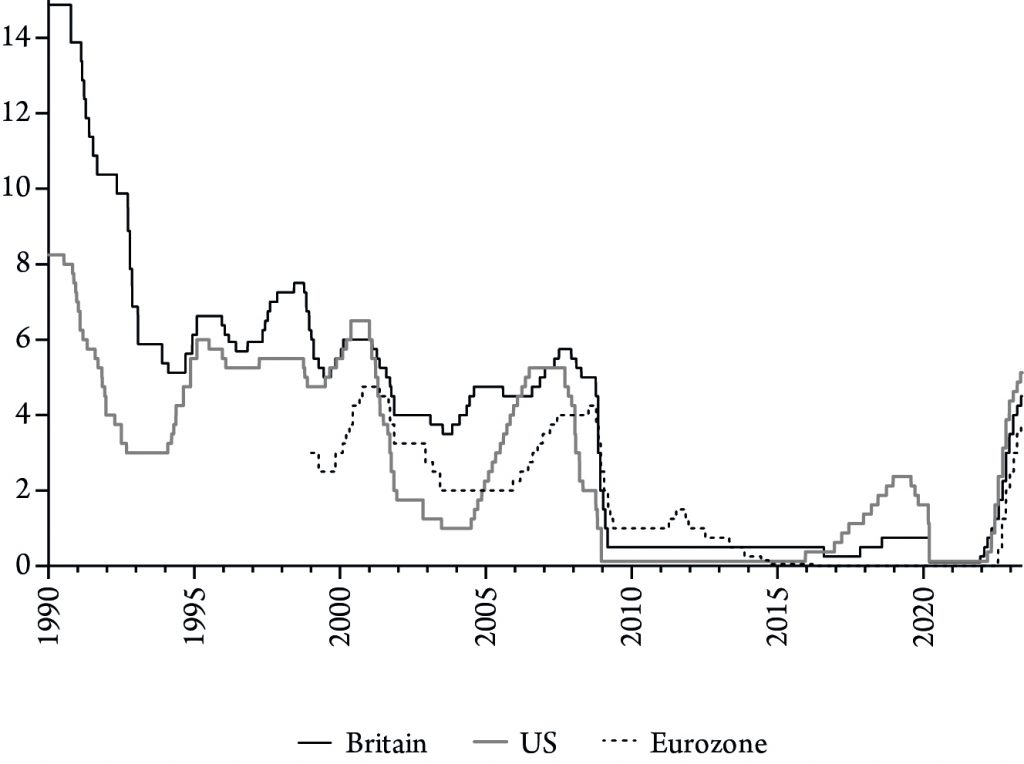

We should, of course, be wary of economic forecasts. Here in Britain, the International Monetary Fund and the Bank of England (BoE) have grudgingly acknowledged they have been consistently wrong in their projections for growth and inflation. BoE chief economist, Huw Pill, offered the rather lame excuse that prediction only worked in times of economic stability.3 Both bodies have now ditched their most gloomy predictions that the country would face the longest recession in a century. However, unusually stubborn inflation (figure 1) and the increase in the BoE’s interest rates in response (figure 2), still threatens to crash the economy.

Figure 1: CPI Inflation and “core” inflation rates for Britain and the OECD

Source: OECD data.

This highlights the dilemma facing those presiding over capitalism—much of the system has become reliant on ultra-low interest rates, yet the only mechanism widely accepted by the ruling class to control inflation is to raise interest rates. That dilemma is not simply a vexatious policy issue; it reflects how the deeper contradictions of capitalism play out in contemporary conditions. This brief analysis will explain why this is the case and explore some of the problems now emerging across the world economy.

Figure 2: Central bank policy rates of interest

Source: Bank of International Settlements data.

The low interest rate regime

Karl Marx’s writings point to a central contradiction within capitalism. On the one hand, the system relies on the creation of new value through the exploitation of workers. Indeed, a fundamental claim of Marxist political economy is that the work of this “living labour” is essential to generate new value under capitalism.4 On the other hand, because capitalism involves competition, capitalists are compelled to reduce the cost of individual commodities. This typically means automation, that is, increasing the weight of “dead labour”: machinery and other means of production produced by past labour. All else being equal, the value of this “dead labour” passes into the final commodities, but, because it is also purchased by capitalists at its value, no new value is created by its use. “Living labour” is thus distinctive because the value required to reproduce it (the wage) is not directly related to, and can be less than, the total value it creates.

The process of automation benefits capitalists able to make the required investments as early as possible. However, once advances in production generalise and prices fall to levels reflecting the value now contained in individual commodities, the overall result is a dilution of the amount of “living labour” set in motion relative to “dead labour”. The result is a tendency for the rate of profit—the ratio between profit and investment—to fall across the system. This pattern is now well attested by empirical studies.5

For Marx, the falling rate of profit was not irreversible. It could be arrested by mechanisms such as increasing the exploitation of workers or by a sufficiently rapid decrease in the price of the means of production. However, it was moments of crisis that offered a particularly effective solution to the problem. Crisis, for Marx, was when the “momentary suspension of all labour and annihilation of a great part of the capital violently lead [capitalism] back to the point where it is enabled to go on fully employing its productive powers without committing suicide”.6 Crisis destroys or devalues some of the mass of “dead labour” that has built up, for instance, through fire-sales of unsold goods or outright bankruptcy of failing firms. This works alongside the collapse of some of the mass of debt and increasing pressure on workers’ wages due to rising unemployment, eventually restoring the profitability for those capitalists who survive.

Over time, changes to capitalism have blunted this mechanism of crisis resolution. As I wrote previously:

As the units of capital swell to enormous size, and interlock with the state and financial system, the problem today known as “too big to fail” comes to the fore. States, which came to play a major role within the capitalist economy through the 20th century, are forced to decide whether to allow the painful process of crisis to take hold, in the hope that the resulting “creative destruction” will restore the capitalist system to health, or whether to bail out and support failing firms…to avoid a catastrophic slump as some of these corporate behemoths fail. The tendency of big firms to engage…directly with financial markets exacerbates the problem, as the failure of one firm can easily affect other, seemingly unrelated, ones.7

As a result, in countries such as the US and Britain, low profitability has been locked in—helping to explain stagnating productivity and tepid growth. Under conditions of low profitability, credit expansion and financial exuberance, rather than intensive investment in production, have played a major role in driving the economy forward. Multiple bubbles have emerged, underpinned by a mega-bubble of credit, culminating in the recent “everything bubble”, in which prices of “assets ranging from cryptocurrencies to vintage cars” surged as investors “chased yield”. As one commentator recently put it, loose monetary policy “kept zombie businesses afloat and swamped Silicon Valley” with cash, while “companies and governments availed themselves of cheap credit to take on more debt”.8

This pattern has begun to spread to other major economies such as that of China. China saw its rate of profit decline rapidly during its boom. As it reached the limits of its earlier export-fuelled expansion—due to the 2008-9 crisis, the pandemic and growing geopolitical tensions—it too has turned to credit expansion and state stimulus.

Short of a full-scale slump, global capitalism will continue to rely on central banks supporting low interest rates, along with mechanisms such as quantitative easing and, in moments of distress, direct state intervention. This was seen dramatically during the Covid-19 downturn, in which bankruptcy and default rates fell as states stepped in to support capital and prop up labour markets. As figure 2 shows, the pandemic also put a stop to efforts to raise interest rates from the ultra-low levels they had reached by 2009. Even before the inflationary surge, a growing number of policymakers and commentators were pointing to instability generated by loose monetary policy, fuelling an ever-expanding financial system with an insatiable appetite for high-risk, high-yield investments.

Inflation and interest rates

The disruption to supply chains and labour markets during the pandemic lockdowns, as well as the war in Ukraine and the ongoing disruption to production from climate change, ultimately forced the issue, driving inflation in many countries to levels unseen in decades. One astute left-wing economist, Isabella Weber, suggested early on that governments could respond with price controls—and was met with ridicule by much of the economics establishment.9 Opinions have since softened, with Weber herself helping to craft a “gas-price brake” in Germany. The French government has secured a voluntary deal with retailers on food prices, and even ministers in Britain are toying with similar schemes.

Nonetheless, in line with the economic orthodoxy, the key weapon to fight inflation has been interest-rate rises. These are a blunt instrument indeed. They function by increasing the cost of borrowing, so subduing business and consumer spending, investment and hiring. As unemployment rises, workers will, it is anticipated, rein in their wage demands, eliminating a “wage-price” spiral. In countries such as Britain, this approach has had a limited impact. Much of the early inflation was imported via rapidly rising food and energy costs or problems in global supply chains. These price rises were passed on to consumers, notably by large energy suppliers and supermarkets. Once inflation took hold, other firms with sufficient weight in the market sought to boost their profit margins by raising prices. This “greedflation” appears particularly bad in Britain, where “core” inflation, stripping out energy and food prices, has ticked upwards recently (figure 1). Given that wage rises lag well below inflation, it is more relevant to talk about a “profit-price” spiral than a wage-price one.

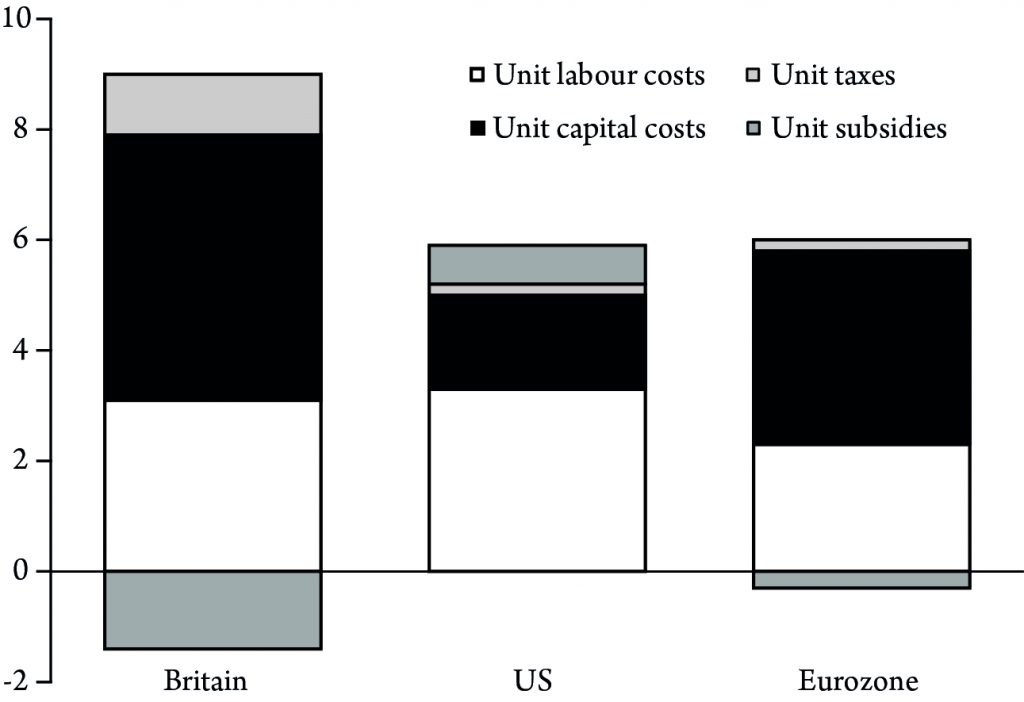

Several authors have examined the role of corporate profiteering in the cost of living crisis.10 Although the evidence remains contested, even the work of Jonathan Haskel, a member of the BoE monetary policy committee apparently eager to absolve corporations of the blame, cannot obscure the role of “unit capital costs” (that is, the amount of the price increase going to capital), whose contribution to inflation outweighs that of “unit labour costs” (the amount going to workers) in Britain and the Eurozone (figure 3).11

Figure 3: Estimates for contributions to annual “GDP inflation” 2022, quarter 4

Source: Data in Haskel, 2023.

Consequences

The rise in interest rates is placing stress on companies that have come to rely on cheap credit. In Britain, insolvencies are running at their second highest rate in a quarter of a century, just below a brief spike in 2008-9; declarations of bankruptcy by businesses across the European Union have also trended up in recent months, and in the US this figure was on track to be the highest since 2010; corporate defaults have also started rising.12

In the US, where inflation has fallen far more than in Britain and Europe, the Federal Reserve is, as a result, becoming more cautious about future rate rises. Where inflation remains stubbornly high, further rises are more likely, and, as the British chancellor, Jeremy Hunt, has acknowledged, this is so even if they trigger a recession.13

The fear that they might do so is heightened by the problems that have emerged in the banking system over recent months. The US has suffered the second, third and fourth biggest bank failures in its history, with the collapse of First Republic Bank, Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and Signature Bank.14 Each of these was hit because it could not adapt to the end of low interest rates. SVB had a tight relationship with the previously booming tech sector and was awash with cash during the easy money era. It put much of this into long-term government bonds. This was a classic case of “borrowing short, lending long”—using short-term flows of income from depositors to buy assets that would tie up this money for long periods, but ultimately yield a higher return. However, rising interest rates puts downward pressure on bond prices, and this coincided with the slowdown in the tech sector. As deposits were withdrawn, SVB had to sell bonds at a loss. Once this became clear, a bank run began, with news spreading and clients withdrawing money at the click of a button.

Signature Bank had made the fateful decision from 2018 to focus on cryptocurrencies, whose value collapsed with the bursting of the “everything bubble”. It too was hit by a bank run once SVB collapsed. First Republic’s focus was on high-net-worth individuals prepared to accept low interest on deposits in exchange for cheap loans. The rise in interest rates imperilled this business model. As clients began to withdraw their money, First Republic struggled with liquidity and several other major banks extended a lifeline of $30 billion. Despite this, over $100 billion in deposits had been withdrawn by April and the bank was shut down on 1 May.

As pressure grew on several other regional banks, the Federal Reserve stepped in, offering an emergency lending programme. Other central banks took similar action, reflecting fears that the crisis would spread abroad. These were not entirely misplaced. Ten days after SVB’s failure, the Swiss government instructed UBS to swallow up Credit Suisse, the second biggest bank in Switzerland and hitherto its main rival. Credit Suisse had faced a breathtaking series of scandals over recent years. These ranged from criminal convictions for helping drug dealers launder money in Bulgaria and a corruption case in Mozambique, to losing billions through its dealings with disgraced financier Lex Greensill and failed New York investment firm Archegos Capital Management.15 Nonetheless, the bank had not made reckless bets on interest rates nor was it heavily invested in cryptocurrencies or directly impacted by the US failures. It reputedly had a “solid balance sheet and a valuable core business franchise”. Yet, in the wake of the US collapses, depositors departed in droves. As one commentator put it: “SVB did dumb stuff and its depositors were at risk. But if Credit Suisse can suffer a run even though it was liquid and well capitalised, then the same thing can happen to any other bank, anywhere, at any time”.16

So far, that fear has not materialised—indeed many banks are reporting record profits as lending rates rise—but the concerns reflect real pressures on the bloated financial system.

More important for much of the world’s population than the banking crisis is the pressure faced by economies in the Global South. During the easy money period, finance flowed extensively into these countries, encouraging them to borrow on international capital markets. The end of policies such as quantitative easing and the rise in interest rates is now sucking capital back towards the US. Currencies of many Global South countries have plummeted in value, diminishing their purchasing power on world markets. At the same time, these countries face a surge in borrowing costs, particularly where they have borrowed in dollars.

According to the Fitch ratings agency, there have been 14 sovereign debt defaults events since 2020, with more likely to follow. In the whole 2000-2019 period, there were just 19. Belarus, Lebanon, Ghana, Sri Lanka and Zambia are all currently in default.17 In some cases, this has been met with struggle, notably in Sri Lanka, where last year an uprising overthrew the government of Gotabaya Rajapaksa, and in Lebanon, where protesters burned several banks in February in a protest triggered by the Lebanese pound losing 98 percent of its value.

The struggles ahead

The deepening economic gloom also has important political implications in the countries of the Global North, further sharpening disillusionment with the old neoliberal centre-ground and continuing the process of political polarisation we have seen over recent decades. As I discuss elsewhere in this issue, the most prominent political responses from the radical left—left-reformist currents such as Podemos in the Spanish state, Corbynism in Britain and Syriza in Greece—have been tested extremely harshly as they have approached or assumed power within the capitalist state. Thus, it has often been the radical right making the running, with various fascist, right-wing “populist” or authoritarian outfits seizing on the crisis.

Britain is not immune from this process. Here the Conservative Party government has sought to distract from its own gathering political problems through the scapegoating of refugees and migrants. Calibrating the precise degree of racism has created tensions within prime minister Rishi Sunak’s party, with a faction around the Sunak concerned about filling labour shortages. This grouping is at odds with supporters of the home secretary, Suella Braverman. Braverman caused a stir when she appeared at the hard-right National Conservatism Conference in May, attacking migrants, “experts and elites”, transgender rights, “identity politics”, critics of Britain’s history of empire, and the radical left.18 The shift to the right within the ruling party has emboldened fascist forces, who have sought to mount protests outside hotels where refugees are accommodated. Many of these protests have, so far, been successfully confronted by counter-demonstrations organised by groups such as Stand up to Racism, but the left will have to continue to be vigilant about these developments.

Denis Godard’s article on the French strike movement in this issue forcefully argues that challenging fascism is not an alternative to engaging in struggle in the workplaces, but rather a necessarily complement to it. His piece also reminds us of the other dimension of the current economic upheaval: the halting revival of workers self-activity through their use of the strike weapon. France remains the high point of this revival, but there have also been important strikes in countries such as Portugal, Germany and Greece. Here in Britain, the efforts of the union bureaucracy to contain the evolving strike movement have had mixed success. Some unions, such as the GMB and Unison in the health service, or the firefighters’ FBU union, have settled their national disputes, with members, in the absence of a clear route to escalate their action, accepting pay deals falling well below inflation. In other cases, for instance, station staff and train crews in the RMT and train drivers in ASLEF at several rail companies in England, action drags on. Here members are resistant to accepting lousy deals, but trade union leaders are seemingly unwilling to move beyond episodic strike action, thus offering little chance of scoring a knock-out blow against employers. This stands in contrast to some of the localised battles taking place, where more extended strike action has proved successful.19

Then there are groups of workers who have challenged poor deals. That was the case for the Royal College of Nursing, whose members voted by 54 percent to reject a deal recommended by their leadership. The ballot saw the emergence of campaign groups such as “NHS Workers Say No”, expressing the anger at what many saw as a sell-out. Leaders of the Communication Workers Union felt obliged to call off their ballot on a proposed pay deal in Royal Mail amid considerable unrest from rank-and-file members. The annual congress of the University and College Union (UCU), held in May, censured, and came close to passing a motion of no confidence in, its general secretary, Jo Grady, for her mishandling of the dispute and for undermining democratic bodies within the union. There has also been debate within the National Education Union (NEU) about the limits of the action in schools, as well as efforts to coordinate opposition to poor deals across unions. For instance, a 120-strong meeting in London in May was co-hosted by Lambeth and Hackney NEU associations, UCU London Region and NHS Workers Say No.20

Despite these positive developments, we remain a long way from the kind of rank and file organisation required for workers to act independently of the bureaucracy and impose their own strategy on the disputes taking place.21 However, the presence of embryonic networks of rank and file activists, prepared to challenge the union leaders, marks an important step forward, and one that socialists must nurture in the period ahead.

Joseph Choonara is the editor of International Socialism. He is the author of A Reader’s Guide to Marx’s Capital (Bookmarks, 2017) and Unravelling Capitalism: A Guide to Marxist Political Economy (2nd edition: Bookmarks, 2017).

Notes

1 Thanks to Judy Cox, Richard Donnelly, Gareth Jenkins and Sheila McGregor for feedback on an earlier draft of this article.

2 Leahy, Liu, Hale and Ho-him, 2023.

3 Barnett, 2023.

4 For an introduction to Marxist political economy, see Choonara, 2017.

5 See, for instance, the essays collected in Roberts and Carchedi, 2018.

6 Marx, 1993, p750.

7 Choonara, 2018, pp88-89.

8 Chancellor, 2022.

9 A University of Chicago economics exam in 2022 asked how “a ‘real economist’ would respond” to Weber’s proposal—Weber, 2023.

10 Some of the attempts are covered by Roberts, 2022, and Roberts, 2023.

11 Haskel, 2023. “Unit capital costs” are a complicated economic category, which include fixed capital consumption and imputed rental income among homeowners, as well as corporate profits.

12 Based on reports from Eurostat, the European Central Bank, the Office for National Statistics and S&P Global Market Intelligence.

13 Makortoff, 2023.

14 Silvergate, a smaller bank, specialising in cryptocurrencies, was also wound down voluntarily a couple of days before the SVB failure on 10 March.

15 Balezou, 2023.

16 Harding, 2023.

17 Fitch Ratings, 2023.

18 The speech is available at www.youtube.com/watch?v=NS5nh1aD-qM

19 Choonara, 2023, p10.

20 See Socialist Worker, 2023.

21 See Choonara, 2023, pp10-15.

References