The Conservative administration of Rishi Sunak, the fourth Tory prime minister in as many years, appeared to be limping into oblivion as our autumn issue went to press.1 A piece by the chief political commentator at the Financial Times compares the current government’s state to the dog days of John Major’s in the late 1990s: “In those final months, Tory MPs stopped believing they could win the next election, leadership contenders prioritised their own ambitions, and media supporters argued over how to shape the party after a defeat. Above all, voters simply stopped listening to the Tories”.2

Waiting in the wings is the Labour Party’s leader, Sir Keir Starmer, whose shadow cabinet reshuffle in September saw members of the Blairite wing of the party, such as Liz Kendall, Peter Kyle, Darren Jones and Pat McFadden, return to the front line of politics, largely at the expense of soft-left MPs. They will lead a party eager to reassure British capital that Labour will secure its interests. Over the summer, Starmer and his shadow chancellor, Rachel Reeves, ruled out additional wealth taxes, the creation of a publicly-owned energy company and the proposed lifting of the two-child cap on welfare benefits. They also postponed their £28 billion “green prosperity” programme, thus proving to markets their fiscal responsibility.

Despite such unpopular moves, Labour retains a comfortable lead in the polls. Yet, any incoming Labour government will face a similar array of societal crises to those that have confronted successive Tory administrations. The economy remains in a parlous state; ecological catastrophe is becoming an increasingly disruptive factor; and there is growing geopolitical upheaval, reflected in the war in Ukraine as well as the tensions between the United States and China.

Labour remains a party committed to managing capitalism, seeking to reform it only within limits set by capital.3 Moreover, those limits are relatively tight today. Though Jeremy Corbyn also accommodated to pressures from the ruling class, Starmer’s proposition—scant reforms and a large dose of counter-reforms—far more accurately reflects the long-term trajectory of Labourism in Britain.4

We can also dismiss the notion that any Starmer-led government will erect barriers to the continued racist offensive in Britain. If Sunak loses the coming election, we should expect the Conservatives to further embrace radical right-wing populism.5 History shows that because Labour prioritises a presumed national interest over that of the multiracial working class, its leadership repeatedly buckles to such pressures. Worse, Starmer is seeking to broaden his appeal to disillusioned Tory voters by explicitly mobilising racist sentiment, promising to outdo the Tories when it comes to halting refugees making small boat crossings to Britain.

For socialists, initiatives to blunt the racist offensive and challenge an array of far-right mobilisations, which have been directed in particular at refugee accommodation, will remain crucial in the period ahead. Stand up to Racism has played an important role disseminating an anti-racist message and, through its counter-mobilisations, preventing groups such as Britain First, Patriotic Alternative and Turning Point UK cohering into a major national movement.6

Amid the dispiriting state of mainstream British politics, it is the working-class movement’s “halting recovery” that provides hope for an alternative to the Tories and Starmer’s Labour.7 The rest of this analysis will consider the extent to which this uptick in struggle has been reversed and will then offer some lessons from the strike wave so far.

Cresting the wave?

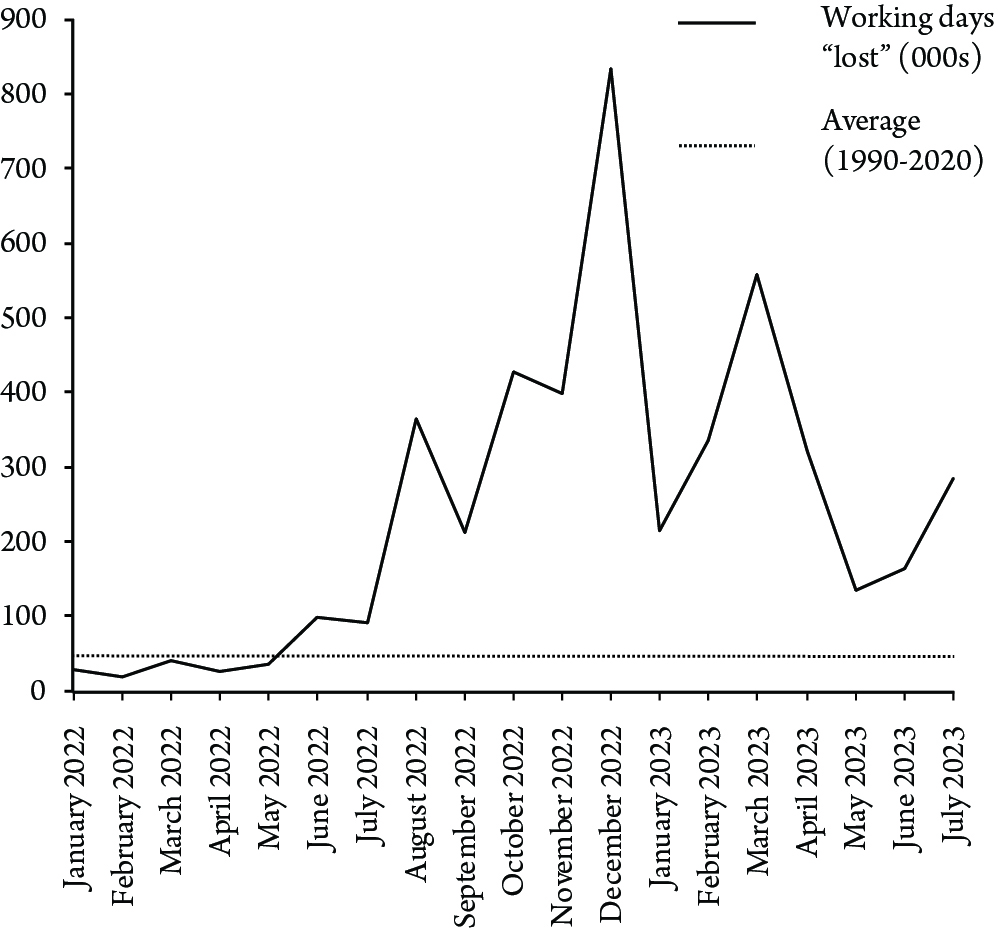

As figure 1 shows, the wave of strikes since summer 2022 experienced a number of peaks. In August and December 2022, over 85 percent of strike days were in transport and communication, primarily on the railways and in Royal Mail. By March, the action had shifted to centre on the education sector (63 percent), especially schools, along with the National Health Service (20 percent).

Figure 1: Monthly strike figures

Source: Office for National Statistics data.

We are no longer at the luminous summits of the strike wave. Most of the major national disputes that emerged in 2022 have been contained, with members voting to accept below-inflation pay deals presented by union leaders. Nonetheless, by July 2023, the final month for which data is currently available, strike activity remained elevated compared to average levels since the start of the 1990s. At the time of writing, national strikes were set to continue among junior doctors and consultants in the NHS and parts of the railways.8 There have also been more localised strikes in bus companies, councils, charities (most notably the St Mungo’s homelessness charity), media organisations, aviation, food and drink producers, and the civil service.9 Given continued pressure on workers’ living standards, these are unlikely to subside entirely in the coming months.

Four lessons

(1) Strike action remains effective: The uptick in strike action in Britain, as in other countries, challenges the notion that workers are unable to fight collectively to defend their interests. Unions have won large mandates for strike action, exceeding the 50 percent turnout required by draconian anti-union laws.10

The only group of workers to win an increase in income sufficient to offset the rising cost of living at a national level were criminal barristers, who declared indefinite strike action in September 2022. However, even the limited and episodic action called by other unions allowed workers to win more than if they had not fought. The proposition that more could have been won through sustained action remains untested at a national level. Tragically, the vote by the Higher Education Committee of the University and College Union (UCU) to undertake indefinite action was blocked by the union leadership in early 2023.11 At a local level, some workers, including some on the buses and in local government, did win better deals through more determined and sustained action.12

Although the limitations to the strikes are discussed below, many workers will draw positive conclusions, seeing that they can achieve the turnout required to win a ballot and win some things through use of the strike weapon. Putting strikes back on the agenda for millions of workers is a significant accomplishment.

(2) The union bureaucracy remains a conservative force: Unions are not homogenous bodies. Alongside rank and file workers, they contain a bureaucracy composed of salaried officials, removed from the workplace, whose main function is to negotiate the terms under which workers are exploited. This bureaucracy is a vacillating force, giving some expression to discontent but also seeking to hold it within tight limits. Replacing more conservative union leaders with more radical ones can make a difference, but ultimately the issue is structural, rather than being one of the personality and politics of this or that leader.13

The counter to the conservatism of the bureaucracy is rank and file organisation, ideally capable of and willing to take unofficial action or, at least, able to pressure the bureaucracy to act. The defeats suffered by the unions from the late 1970s onward have tended to be self-reinforcing. By undermining the confidence of rank and file workers, they strengthened the hold of the bureaucracy, further limiting the success of industrial action. Indeed, the bureaucracy often relies on the support of more passive, cautious or demoralised rank and file members.

The way out of this cycle of defeat and demoralisation will involve using official action, even in a limited form, to create networks of union activists that can become the germ of rank and file organisation. This involves building official action, even if it is less effective than it should be, while also explaining the limits of this action and of the union bureaucracy. Neither glib enthusiasm for strikes that fall short of what is possible nor passive denunciation from the sidelines will achieve the necessary breakthroughs.

(3) Significant numbers of trade unionists question the retreats: Fortunately, there is now a significant base of support for such an approach in many unions. Though this does not, in most cases, currently translate into a willingness to take unofficial action, large numbers of union members have voted to reject poor deals on pay and other issues.

Table 1 summarises this. It leaves out an array of smaller votes by unions in local disputes and some of those in multi-union workplaces such as the NHS. When these are taken into account, it is clear that close to quarter of a million trade unionists have voted against deals put to them by their union leaderships.14 This is a considerable audience within which to seek to build embryonic rank and file organisation. There are also already some basic grassroots organisations forming within the unions, such as NHS Workers Say No or UCU Solidarity Movement, that mobilise independently of formal union structures.

| Union and sector |

Percentage rejecting |

Number rejecting |

|

CWU |

19 |

4,500* |

|

RMT |

24 |

4,300 |

|

RCN |

54 |

93,500 |

|

Various unions |

25 |

40,000 |

|

CWU |

25 |

17,000 |

|

NEU |

14 |

25,000 |

|

NEU |

27 |

2,100 |

|

NEU |

15 |

3,300 |

|

UCU |

33 |

11,789 |

|

PCS |

10 |

7,000* |

|

RCM |

43 |

5,300 |

|

FBU |

4 |

1,000 |

|

EIS |

10 |

3,000* |

|

Total |

|

217,800 |

(4) Revolutionaries’ role is vital: The role of revolutionaries is vital here for three reasons. First, and most obviously, our commitment to collective workers’ struggle at the point of production means that we are often directly involved in building strikes and in preventing sell-outs and retreats. Take, as evidence, the recent vote to accept a below-inflation pay deal by teachers in the National Education Union (NEU) in English schools. Overall, 14 percent of teachers voted to reject. However, in the 16 NEU districts with the highest vote to reject, each with over a quarter voting against, 12 had members of the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) among their leadership.15

Second, revolutionaries base themselves on the general interests of the “proletariat as a whole”.16 This means rejecting the sectionalism that has afflicted British trade unionism as well as the movement’s subordination to the reformism of the union bureaucracy and the Labour Party. Such an approach is essential if the aspiration is to turn whatever rank and file organisation can be built into a rank and file movement capable of fighting on “the general class front”, linking “workers in different localities and industries”.17 Though, again, only an embryonic stage in this process, the decision to hold a Workers’ Summit in London on 23 September was a positive step in the right direction. Members of the SWP have played an important role in this initiative.

Third, an important characteristic of reformism is a division between economics and politics—institutionalised in Britain in the form, respectively, of the union bureaucracy and the Labour Party. Revolutionaries know no such limitation. Indeed, our ultimate goal is to use the economic power of workers to elevate them to political power through a revolutionary process.

Workers’ movements flounder not simply on economic questions but also on political ones. It is essential, for instance, that issues of oppression, such as the fight against racism, is made the property of the workers’ struggle. In this sense, building workplace organisation and building Stand up to Racism are not opposed goals but part of a unified strategy to advance the working-class struggle. It is also the case that explosions of activity can originate outside of the workplace, through political crises. Revolutionary organisation plays a central role both in linking together the various struggles and developing a clearer theoretical understanding of the situation in which we find ourselves to guide activity.

Given the key role of revolutionary socialists, implementing the lessons from the past year, and ensuring greater success in future struggles, means, among other things, increasing the size and weight of our own forces by building and revitalising revolutionary organisation.

Joseph Choonara is the editor of International Socialism. He is the author of A Reader’s Guide to Marx’s Capital (Bookmarks, 2017) and Unravelling Capitalism: A Guide to Marxist Political Economy (2nd edition: Bookmarks, 2017).

Notes

1 Thanks to Mark L Thomas, Camilla Royle, Gareth Jenkins, Judy Cox and Sheila McGregor for comments on earlier drafts.

2 Shrimsley, 2023a.

3 A classic statement of the argument is Cliff and Gluckstein, 1996.

4 Kimber, 2020. The most significant departure from the administrations led by Tony Blair and Gordon Brown is that, where they accepted much of the neoliberal rhetoric of the withdrawal of the state from economics, Starmer and Reeves acknowledge the state has a role to play. This is no shift towards socialism. It follows a similar logic to that of the Joe Biden administration in the US—accepting that the state should be deployed to buttress capitalism against its own crises and to engage in intensified inter-imperialist rivalry, especially with China—see Choonara, 2021.

5 For a description of the various motley groups waiting in the Tories’ wings, see Shrimsley, 2023b.

6 Stand up to Racism, 2023.

7 Choonara, 2023.

8 Kambiz Boomla’s article in this issue draws some lessons from an earlier wave of industrial action in the NHS.

9 For a heroic effort to summarise the strike picture nationally, see Moss, 2023.

10 See Dave Lyddon’s article in this issue for a historical analysis of anti-union laws.

11 Choonara, 2023.

12 See, for instance, Ringrose, 2022. See also Ord, 2022.

13 See Choonara, 2023 and the references therein for longer discussions.

14 Thanks to Mark L Thomas, of the Socialist Workers Party’s workplace and union organising team, for compiling the data for Table 1. The UCU figure is for the March ballot over “pausing” the dispute to allow talks. The consultative ballot in the PCS was on the basis of continuing the pay campaign but “pausing” strikes.

15 Again, thanks to Mark L Thomas for this analysis of the NEU voting data.

16 Marx, 1973, p119.

17 Callinicos, 1982.

References