The extraordinary British general election of 8 June 2017—held amid the echoes of police gunfire on London Bridge—showed that the forces destabilising the advanced capitalist societies since the global economic and financial crisis that broke out nearly a decade ago in August 2007 are still at work. Paradoxically, however, these forces have operated partially to revitalise the old two-party system that had been buckling under the pressure of a decades-long crisis of the British state and of the political forms through which it has secured the hegemony of the dominant capitalist coalition.1

But above all the election saw the Labour Party under Jeremy Corbyn—derided and despised by the other parties, by the media, by most of his MPs—win its highest share of the vote since Tony Blair’s second landslide in 2001 and deprive the Tories of a parliamentary majority. This astonishing achievement relied not on the slick media savvy political technology of the neoliberal era, but on a mass campaign in support of a left wing anti-austerity manifesto.

To understand what happened we have to set the Corbyn movement’s success alongside the advances of the radical left elsewhere—for example, the election of Syriza and the anti-austerity referendum in Greece in 2015 and Bernie Sanders’s successes in last year’s Democratic Party primaries. Contrary to the assumption of too many on the liberal and even radical left, the Brexit referendum did not expose British (or at least English) society as irredeemably reactionary (or indeed Scottish society as qualitatively more progressive, which the Tory advance north of the border contradicts). In Britain as in other countries, the effects of the crisis and its long aftermath are beginning to crack open the neoliberal order, strengthening both radical left and radical right, anti-racism and racism, progress and reaction.

But here and now it is the right that is on the back foot. Theresa May’s snap election has proved to be one of the most disastrous miscalculations of modern British politics.2 It invites comparison with two snap elections called by earlier Tory prime ministers—Stanley Baldwin’s attempt to win a mandate for Protection (import tariffs) in December 1923 and Ted Heath’s “Who Governs Britain?” election in February 1974. In both cases the result was defeat and a minority Labour government. This time May is trying to cling on to office with the support of the ultra-Loyalist Democratic Unionist Party (DUP). But the writing’s on the wall.

The wages of Brexit

May’s decision to call the election reflected the convergence of two factors. The first was, of course, the vote to leave the European Union on 23 June last year. Having been a tepid supporter of staying in the EU, May transformed herself into an enthusiast for Brexit. This was, in part, a matter of simple opportunism. After winning the premiership thanks to the self-immolation of the Brexiteers and to her own reputation as a safe pair of hands, May embraced Brexit. Indeed she did so in terms—leaving the Single European Market and escaping the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice (ECJ)—that would ensure a “hard Brexit”. She hoped both to reunify her own party, which had been badly split by the referendum, and to recapture some of the electoral ground the Tories had lost to UKIP, particularly in the 2015 general election.

But ideology as well as opportunism has played its part in this choice. For nearly 20 years what one might call cosmopolitan liberalism was politically dominant in Britain. This involved a combination of economic liberalism—in other words, a commitment to neoliberal economic policies—and social liberalism —progressive attitudes on issues such as LGBT+ rights. This was underpinned by participation in the multilateral institutions built up since the Second World War by the United States as means of securing its hegemony (NATO, the EU, the World Trade Organisation, etc). The leading politicians of this era—Tony Blair and David Cameron and their chancellors of the exchequer, Gordon Brown and George Osborne respectively—embodied this kind of cosmopolitan liberalism. As everyone knows, this politics suffered two major defeats last year—the Brexit referendum and the election of Donald Trump.

Now May doesn’t necessarily reject cosmopolitan liberalism—in particular, she lacks the intellectual originality, the class interest, or the social base to break with neoliberalism. But undoubtedly she has sought to give the dominant ideology a more nationalist, authoritarian and economically interventionist cast. Of these three elements, the last is the most vague. With Margaret Thatcher, economics was plainly in command, but it’s hard to know how seriously to take May’s talk of helping “working people” and correcting “market failure”.

The best known socio-economic policy she devised, apparently with the help of her leading strategist Nick Timothy—the “dementia tax” abandoning any cap on the financial contribution made by those needing social care—was mean-spirited, socially regressive and politically disastrous. The fact that May and Timothy admire Joseph Chamberlain (1836-1914), the Birmingham Radical turncoat who helped keep the Tories in office for 20 years, fought Irish Home Rule, and championed imperialism and protectionism tells you all you need to know about them. Allying with the Paisleyite bigots of the DUP is right up May’s street.

Her heart is clearly in it when she seeks to restrict migration and resist judges seeking to defend human rights. In this she reflects the nasty, repressive ethos of the Home Office, which she headed for six years under Cameron. Will Davies describes how in conversations with Home Office officials:

a powerful image emerged of a department that had been embattled for a long time. In an era in which national borders were viewed as an unwelcome check on the freedom of capital and (to a lesser extent) labour, and geographic mobility was regarded as a crucial factor in promoting productivity and GDP growth, the Home Office, with its obsession with “citizenship” and security, was an irritant to the Treasury and the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills. There has been an ideological conflict in Whitehall for some time regarding the proper relationship between the state, markets and citizens, but it has been masked by the authority of a succession of prominent, ambitious chancellors pushing primarily economic visions of Britain’s place in the world. One can imagine the resentment that must have brewed among home secretaries and Home Office officials continually represented as the thorn in the side of Britain’s “economic competitiveness”.3

Winning the premiership on the back of the Brexit vote gave May the opportunity not only to settle old scores with the likes of Osborne, but to assert the priority of national sovereignty and security. In all probability it was the prospect of being able to scrap free movement of labour and break loose from the ECJ that led her to reject a Brexit deal that involved Britain staying in the Single Market, which chancellor Philip Hammond ineffectually pressed on her. The weakening of the Treasury, the main bastion of cosmopolitan liberalism in the British state, is underlined by the way May rebuffed City lobbying not to leave the Single Market and in last year’s Tory conference speech denounced “citizens of nowhere” who sought to break free of national identity. As in the US since Trump’s victory, base and superstructure have got badly out of sync.4

David Runciman describes the speech as “surprisingly reckless”, indicating that, alongside her widely publicised qualities of diligence and stubbornness (May eventually embraced Ken Clarke’s description of her as “a bloody difficult woman”), she is as much a gambler as Cameron was in calling two referendums that nearly broke up the United Kingdom state and took it out of the EU.5 As one pro-Tory columnist contemptuously puts it, “under Mrs May, and before her Mr Cameron, leadership became the low art of doing whatever tactical trick gets you through the week until the gradual build-up of contradictions and liabilities gives rise to an unsurvivable crisis”.6

What made calling the election seem not to be such a gamble was a second factor. May shared the view of the rest of the political and media elite that Labour was there for the taking. This was partly a function of the conventional wisdom about Corbyn—most assiduously spread by his own MPs—that he is a feeble left wing loser, “unelectable”, a modern version of the failed left wing party leaders of the past, George Lansbury and Michael Foot.

But there was also the Brexit effect. Britain’s EU membership has always been an issue that cuts across normal party allegiances (and indeed the division between left and right). UKIP was able to build itself up to be—in terms of votes, although not parliamentary seats—the third biggest party in the 2015 election by winning the so-called “left behind” voters—relatively poor, less educated and older people who no longer felt represented by the main parties.7 Initially it was the Tories that seemed most vulnerable, but increasingly Labour in its working class heartlands in the Midlands and the North was threatened too.

Then came the EU referendum. While Labour campaigned to remain, 35 percent of its voters backed leaving.8 This was widely seen in political and academic circles as a tipping point that would precipitate conservative working class Labour supporters rightwards. By making Brexit the main election issue (and complaining about the obstructionism of a House of Commons that voted overwhelmingly to trigger article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty and thus to initiate Britain’s departure from the EU), May and her advisers such as Timothy and the Australian Machiavelli Lynton Crosby hoped to roll up UKIP and tip many Northern and Midlands Labour seats into the Tory camp. This script was accepted by the bulk of the establishment. Up to the very day of the election the media were full of stories about Labour’s vulnerability to Tory inroads into its heartlands.

This calculation didn’t prove completely wrong. UKIP, which has imploded since its triumph in June 2016, was virtually demolished, seeing its share of the vote drop by 10.8 percentage points. And how constituencies had voted in the referendum was related to whether they tilted towards Tories or Labour. According to John Curtice, architect of the exit poll that tolled doom for May’s dreams of a landslide, “on average, there was a one point swing to the Conservatives in seats where over 60 percent of people voted Leave in 2016. In contrast, there was a seven point swing to Labour in seats where more than 55 percent voted Remain”.9

Nevertheless, on the whole Brexit was the dog that didn’t bark on 8 June. We can see this in the fate of the parties that made a point of opposing Brexit—the Liberal Democrats, Greens and, to some extent, the Scottish National Party (SNP). All lost vote share, though the Lib Dems picked up four extra seats on a slightly reduced share (7.4 percent compared to 7.9 percent in 2015), while the Greens, who denounced Corbyn for supporting the triggering of article 50 and campaigned for a “progressive alliance” against the Tories and a second referendum on Brexit, dropped from 3.7 to 1.6 percent. Much more importantly, the swing to the Tories in pro-Leave constituencies wasn’t enough to sweep up many Labour seats. On the contrary, it was Labour that made major advances in southern England and consolidated its dominance of London, where it took an astonishing 54.5 percent of the vote (to the Conservatives’ 33.2 percent), and even narrowly captured the ultra-Tory seat of Kensington.

To explain this one must start with a simple fact highlighted on the eve of the election by Bill Emmott, ex-editor of The Economist: “‘Europe’ does not score highly among the issues that matter for British voters, whether they are for or against membership of the EU”. (Emmott reveals his own preferences when he calls this “the true failure of the pro-EU cause in Britain over the past 44 years…a tragedy for Britain and its strategic interests”.)10 But the relatively low salience of the European issue for most British voters has allowed many who voted to remain a year ago to accept the inevitability of Brexit. Marcus Roberts of YouGov writes:

On the question of Brexit, the electorate can be broken down into three core groups instead of two: the Hard Leavers who want out of the EU (45 percent); the Hard Remainers who still want to try to stop Brexit (22 percent); and the Re-Leavers (23 percent)—those who voted to Remain last summer but think that the government now has a duty to leave.

The emergence of this latter group means that when the parties are discussing Brexit, they should not think in terms of two pools of voters split almost down the middle. Instead, there is a big lake made up of Leave and Re-Leave voters and a much smaller Remain pond. This means that the Conservatives and UK Independence Party are fishing among 68 percent of voters, while Labour, the Liberal Democrats, Greens and nationalists are battling for just 22 percent of the electorate.11

Roberts’s analysis—and his prediction that May would win a landslide—puts Labour in the category of anti-Brexit parties. But this is precisely where Labour under Corbyn refused to be placed. Despite a chorus of disapproval from the Guardian-reading classes and the defiance of 52 diehard Remainer MPs, he whipped the Parliamentary Labour Party to vote for the bill triggering article 50 during its rapid passage through the House of Commons. This made it much harder for May to brand Labour as anti-Brexit, and it allowed the Corbyn team to concentrate on campaigning for the social and economic content of their manifesto. The issue became, not for or against Brexit, but what kind of Brexit?

Corbynism connects

The political scientist Jonathan Wheatley distinguishes between “two dimensions of political opinion” that can be used to identify where people stand in the right-left spectrum”:

The first is an economic dimension about whether you prefer pro-free market economic policies on the one hand, or redistribution of wealth and a greater role of the state in the economy on the other. The second is a cultural dimension, which I referred to as communitarian-cosmopolitan, but which other commentators have described as “open versus closed”. It concerns the relationship of your community with the outside world, draws on issues such as EU membership and immigration.12

Wheatley’s research suggests that by the time of the general election Tory and Labour supporters had become more polarised along both dimensions compared to 2015, with:

a wide gap in the middle that is not occupied by any party’s supporters. This, perhaps, reflects the legacy of last year’s referendum campaign, which may have led to a polarisation of preferences.

In reality, the middle is not empty and, given the recent volatility in the opinion polls, most likely contains large numbers of undecided voters. It is these that all parties, and especially the two main parties, will need to win over. For Labour, the dilemma is that they need to draw from two very distinctive support bases. On the one hand, there are the traditional Labour heartlands of the North and the Midlands, whose voters often take a “closed” position on the cultural dimension, and may have voted for Brexit or even toyed with UKIP in 2015. On the other are young cosmopolitan “open” voters, typically from London or the Home Counties, who may also consider the Lib Dems or the Greens. These two support bases seem to have moved further apart after last June’s referendum and are hard to accommodate in a single “tent”. From the evidence presented here and from opinion poll evidence, the latter group seem to have swung clearly behind Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour Party, while the former remain open to persuasion.13

As Wheatley also notes, “Theresa May has consciously attempted to target ‘closed’ economic leftists”. We can now see that she has failed and that Labour was able to overcome its dilemma. This can’t just be explained negatively, by May’s lacklustre campaign and the catastrophic error she made in proposing the dementia tax. Corbyn and his supporters were able to make a positive appeal. Their manifesto proved not to be a repeat of the 1983 Labour manifesto, “the longest suicide note in history”—Gerald Kaufman’s famous quip, which lazy journalists repeated after a draft was leaked with the London Evening Standard screaming: “Comrade Corbyn Flies the Red Flag” (16 May).

In fact, Corbyn and his shadow chancellor John McDonnell offered what would have been in the Keynesian era (1945-75) a solid social democratic programme—higher taxes on the rich and affluent, borrowing to fund infrastructural investment, a National Investment Bank, ending privatisation in the National Health Service, establishing National Education and Care Services, bringing rail, water, electricity and the Royal Mail back into public ownership, improving workers’ rights, attacking the abuses of the gig economy, preserving the triple lock on pensions, scrapping university tuition fees, and restoring the Education Maintenance Allowance.

The context—40 years of neoliberalism, nearly a decade of austerity—made these proposals radical. Even Polly Toynbee—apologist first for the Social Democratic Party split from Labour and then for Blairism—described the draft as “a cornucopia of delights…a treasure trove of things that should be done, undoing those things that should never have been done and promising much that could make this country infinitely better for almost everyone”. She just worried that association with Corbyn might discredit a set of good proposals.14

After the election the mainstream media and Labour right wingers took a different line, conceding that “of course, Jeremy is a good campaigner”. This suggests that the difference between him and May was just a matter of technique and personality. In fact, the content and organisation of the Labour campaign were crucial. Corbyn ran as a socialist fighting for an end to austerity. Like May, he was offering an alternative to cosmopolitan liberalism, but on a progressive and internationalist basis. So the manifesto made a difference. Moreover, the Corbyn team took a step towards their goal of transforming the Labour Party into a social movement. A wave of mass rallies criss-crossed the country, buttressed by skilful use of social media. Moreover, previously stalemate had reigned within the Labour Party, with Corbyn enjoying the support of the mass membership but stymied by the right’s control of the machine nationally and locally. Momentum, created to provide him with a powerful base of activists, had been paralysed by internecine factional debates.

During the election campaign Momentum came into its own, mobilising its members as a canvassing strike force. The Corbynistas ceased to be just an online presence and began to exert real influence on the ground. Their activities were reinforced by a wave of anti-austerity protests and local days of action, often organised by Labour Party members and militants of the far-left (including the Socialist Workers Party). All these initiatives now had a common political focus that united a hitherto fragmented and mutually antagonistic radical left, whether in or outside the Labour Party—to kick out the Tories, back Corbyn and vote Labour.

This is the context in which the surge in youth participation in the election must be seen. According to YouGov, Corbyn captured the youth vote along a broad front—66 percent of 18 to 19 year olds, 62 percent of 20 to 24 year olds, and 63 percent of 25 to 29 year olds voted Labour, but also 55 percent of thirtysomethings and a plurality (44 percent) of fortysomethings.15 Young voters’ support for Labour can’t be reduced to specific issues—opposition to Brexit or Corbyn’s promise to scrap tuition fees. One ingredient in the political upheavals unleashed by the crisis has been waves of youth radicalisation, internationally the Occupy movement in 2011, in Britain the student protest movement of 2010. Victims of an austerity regime that offers them a future of low-paid jobs, scarce and expensive housing and massive student debt, many young people have moved left.

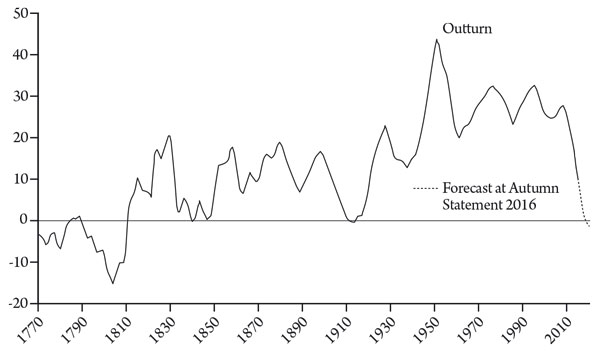

Labour’s economic offer also undercut May’s appeal to “‘closed’ economic leftists”. We originally published Figure 1 showing the sharp drop in real earnings since the economic crisis in International Socialism 153. It bears republishing because it shows who have been paying for the “recovery” from the Great Recession—the “ordinary working people” May promised to defend. And the uptick in inflation caused by the drop in the sterling exchange rate since June 2016 means that real wages will continue to be under pressure from employers struggling with endemic problems of competitiveness and reluctant to engage in productivity-enhancing investment. Real earnings fell by 0.6 percent in the three months to April.16 The experience of squeezed pay and more general austerity, along with fears for the future of the NHS—which May’s empty manifesto did nothing to counter and indeed offered worse in the shape of the dementia tax—must have persuaded many traditional Labour voters who might be attracted to the Tories or UKIP on Brexit or migration to stick with Labour.

Figure 1: Real weekly earnings decadal growth since the 1700s Percentage change in average pay between last 10 years and 10 years before (CPI and predecessors adjusted). Source: Resolution Foundation.

Even an academic supporter of the popular media thesis that the election result was the “revenge of the Remainers”, Matthew Goodwin, after arguing “disproportionately high youth turnout combined with support from urban, pro-Remain liberals allowed Labour to storm through London and university towns”, concedes:

Crucially, Labour also managed to defend some of its more fragile territory in areas that had voted to leave the EU and make a number of other gains. This was not all about Brexit. Clearly, Corbyn’s pledge to tackle economic injustice, push back against the banks, impose higher taxes on the wealthy and renationalise the railways resonated with Britain’s left behind.17

The party’s success in the cities moreover supports more long-term research that urban Britain, with its increasingly ethnically mixed population, is becoming an increasingly favourable terrain for Labour.18 Fraser Nelson, editor of the right wing Tory weekly The Spectator, grudgingly conceded: “We should stop thinking of Corbynism as an anachronism, a relic from the 1970s. There is something horribly 2017 about it”.19

Finally, and remarkably, the Tories’ efforts to use the terrorist atrocities in Manchester and at London Bridge to brand Corbyn as “soft on terrorism” proved a flop. In the last few days of the election campaign, May sought to recapture the ground she had lost by threatening new assaults on human rights. Her own record didn’t help. You can’t serve as home secretary for over six years and respond to two terrorist attacks in the space of a fortnight by talking about your opponent’s conversations with Sinn Féin during the 1980s. But, more importantly, Corbyn could draw on the moral capital he had built up as a leader of one of the biggest anti-war movements in history, who opposed the invasion of Iraq from the start and warned that it would lead to more terrorist attacks. His speech on 26 May criticising the disastrous legacy of Britain’s subservience to US imperialism in the Middle East was a crucial intervention.

Hanging by a string

So a general election that was meant to consolidate the shift to the right sought by the Tory Brexiteers has instead produced an upsurge to the left. As she faces the second hung parliament in less than a decade May has delivered the opposite of the strong and stable leadership she promised. The claims by Tories and Labour right wingers that she nevertheless won the election is patent nonsense. Constitutionally, as the leader of the largest party in the House of Commons, she has first go at trying to form a government. But she has no automatic right to the premiership. In 1923 Baldwin resigned, even though the Tories were still the biggest party in the House of Commons (with 258 seats to Labour’s 191 and the Liberals’ 159), opening the way to the first Labour government under Ramsay MacDonald, after the abandonment of what A J P Taylor called “hare-brained schemes” to avert this outcome.20 Corbyn and McDonnell are entirely right to assert their willingness to form a minority government.

Nevertheless, the parliamentary arithmetic favours a Tory government. This doesn’t mean that the “confidence and supply” deal that May is seeking with the DUP will allow her to stay in office for a full five-year term. To begin with, even the Tories can cling on. May herself is, as a gloating Osborne observed, “a dead woman walking”.21 The Tories mercilessly punish failure, and May’s arrogant and secretive style of governing has left her with few friends. The fact that she had to sack her joint chiefs of staff—Nick Timothy and Fiona Hill, apparently to avoid an immediate leadership challenge, is a sign of her weakness. She may hang on for a bit. Her strongest card is probably the unappealing bunch of potential contenders for the succession. Boris Johnson, David Davis, Amber Rudd and Liam Fox hardly constitute an embarras de richesses.

Secondly, there is the alliance with the DUP. Relying for survival on a bunch of creationist, homophobic, anti-abortionist bigots undermines the government’s legitimacy from the start. Both partners are weak—the Tories because of their electoral defeat, the DUP under pressure from Sinn Féin in the Six Counties themselves. Combining them can simply multiply their weakness. Even if the DUP hold back on pressing their ultra-conservative social views on May, they will demand plenty in the way of pork-barrel measures, as well as support in buttressing the crumbling Protestant ascendancy in the North of Ireland.

The DUP had led the power-sharing Northern Ireland executive for the past ten years until first minister Arlene Foster was forced to resign earlier this year amid allegations of corruption surrounding a failed renewable heating scheme that cost nearly £500 million. Foster originally joined the DUP because she shared its bitter opposition to the 1998 Good Friday Agreement that ended the Troubles. The DUP are sure to use the deal with the Tories to buttress themselves against Sinn Féin. If May lets them destabilise power-sharing, her standing will sink even lower with both the British and the other European ruling classes.22

Thirdly, and most importantly, there is Brexit. May is now in an extremely hard place. There isn’t a parliamentary majority for the kind of radical break with the EU that she has made her own. The Remainers in the cabinet and on the Tory back benches will now press for a much softer Brexit, involving staying in the customs union and perhaps also the Single Market, with strong support from the City and business big and small alike.23 But this will not go down well with the likes of Johnson and Fox and their supporters, whose hand has been strengthened by May’s decision to bring Michael Gove back into the cabinet.

And waiting on the other side of the Channel are the representatives of the rest of the EU. The leaks about a Downing Street dinner in late April from the ineffable Jean-Claude Juncker, president of the European Commission, indicated that the leaders of the EU intend to use similar bullying tactics against Britain to those that broke the Syriza government in Greece.24 Britain is a much bigger economy, an imperialist power with its own currency and central bank, but the fact remains the EU doesn’t do negotiations with individual states—it prefers diktats. The article 50 clock is running, and, without a deal, Britain will crash out of the EU on 29 March 2019, with its trade relations with the rest of Europe disrupted by much higher tariffs. It increasingly looks as if EU leaders, focused on trying to integrate more closely to overcome the eurozone crisis and counter Trump’s challenge to neoliberal globalisation, would (ironically, like the ultra-Brexiteers) welcome such an outcome.25

The Brexit vote and its aftermath—Cameron’s fall and May’s catastrophic snap election—have thus thrust Britain into a period of serious political instability. The problems facing British capitalism, which has yet to recover from the financial crash and the Great Recession, are intensifying.26 And, confounding all the calculations of the political and media elites, the force that offers a way out of this crisis is Labour under Corbyn. The explosion of outrage and anger provoked by the terrible Grenfell Tower fire in north Kensington has brought into even sharper focus the sense of British society as defined by a class antagonism that protects the rich and victimises the poor. It was this sense that Corbyn articulated during the general election. The very political vocabulary used by Grenfell residents and their supporters to describe their plight, words such as “class” and “austerity”, was given a wider currency thanks to his campaign.

One of the most striking features of the 2017 election was the revival of the old two-party system, which has been in decline for decades. One has to go back to 1970, when Heath defeated Harold Wilson’s Labour government as the long post-war boom drew to a close, for a general election where the two main parties won over 80 percent of the total vote (table 1). As we have seen, this time around many of the smaller parties had their vote squeezed. This extraordinary change doesn’t mean that the relative stability of the 1950s and 1960s has returned. Then commentators talked about Butskellism, implying that successive chancellors R A Butler (Tory) and Hugh Gaitskell (Labour) both stood for the same Keynesian, welfarist policies. Now it is a harsh left-right polarisation that has invested and revived the old two-party conflict.

Source: Financial Times.

|

Year (PM) |

Con |

Lab |

LD |

|

1970 (Heath) |

46.4 |

43.1 |

7.5 |

|

Feb 1974 (Wilson) |

37.9 |

37.2 |

19.3 |

|

Oct 1974 (Wilson) |

35.8 |

39.2 |

18.3 |

|

1979 (Thatcher) |

43.9 |

36.9 |

13.8 |

|

1983 (Thatcher) |

42.4 |

27.6 |

25.4 |

|

1987 (Thatcher) |

42.4 |

30.8 |

22.6 |

|

1992 (Major) |

42.2 |

34.4 |

17.8 |

|

1997 (Blair) |

30.7 |

43.2 |

16.8 |

|

2001 (Blair) |

31.7 |

40.7 |

18.3 |

|

2005 (Blair) |

32.4 |

35.2 |

22.0 |

|

2010 (Cameron) |

36.1 |

29.0 |

23.0 |

|

2015 (Cameron) |

36.9 |

30.4 |

7.9 |

|

2017 (May) |

42.4 |

40.1 |

7.2 |

Even the SNP has had its wings clipped after its triumphs in the 2015 Westminster and 2016 Holyrood elections. Its share of the vote in Scotland fell from 50 percent in 2015 to 36.9 percent and 21 of its 56 MPs lost their seats, to both Tories and Labour. May’s snap election wrong-footed Scottish first minister Nicola Sturgeon, who had to row back from her earlier call for a second independence referendum, which proved electorally unpopular. Politics has become competitive again north of the border. Although the Scottish Tory Party leader Ruth Davidson has been talked up for her successful pro-Union campaign, this development opens the way for an advance of Corbynism in Scotland.

There’s a good chance that the instability will lead to a second general election long before 2022. Polls are already suggesting Labour could win this time. This would be the first radical left government in an advanced capitalist society since the Popular Front in France in 1936. Clement Attlee’s Labour government of 1945-51 carried through the greatest programme of progressive reforms of the 20th century, but its members had been schooled as trustworthy managers of British imperialism by serving in the wartime coalition under Winston Churchill. This government would be led by Corbyn and McDonnell, hard-left militants who spent a generation fighting first Thatcherism and then Blairism from the back benches and in a myriad of campaigns and then put themselves at the head of the anti-austerity movements since 2010.

The stakes couldn’t be higher. Should Corbyn and McDonnell take office they would confront the usual enemies within—the civil service and the security and intelligence apparatuses—and without—the financial markets and the corporate media—that confront every reformist government. But short of that they and their supporters face plenty of hazards. Since Corbyn’s victory in the leadership contest—still less than two years ago—dual power has reigned in the Labour Party, with the leader with his mass base constantly being sabotaged, harassed and blocked by a PLP and official machine dominated by leftovers from New Labour. Corbyn’s achievement in the general election has shifted the balance of power in his favour, perhaps decisively. Judged by the ultimate criterion of success for social democratic parties, he has delivered, not (yet) a Labour government, but the party’s biggest share of the vote since 2001, an increase since 2015 of 9.5 percentage points.27

But the Labour right won’t simply go away. Blairism has been very badly wounded, but the strength of its supporters in parliament and the Labour national and local bureaucracy means that it is not, as many have declared, dead yet. The signs that many right wingers are willing to make their peace with Corbyn are a tribute to his success, but can also be a source of pressure to compromise. As it was, the manifesto contained a series of concessions to the Blairites and the soft left—notably the commitment to Trident, support for NATO, and the abandonment of free movement of European labour. The temptation to hearken to the siren call of New Labour—sung, for example, by the arch-Blairite Alastair Campbell on the post-election Question Time—to move onto the centre ground will become stronger the better Labour performs in the polls. Corbynism may have worked a miracle on 8 June, but it hasn’t abolished the logic of electoral politics.28

But Corbyn turned the tables on his internal and external enemies by refusing to follow the counsels of the conventional wisdom, and playing to his strengths—mass mobilisation in support of left wing policies. He needs to continue on this course. This means avoiding like the plague the kind of “cross-party commission on Brexit” being proposed across the political spectrum from William Hague to Paul Mason: this would blur the clear alternative Corbyn offered at the election and potentially tie the hands of a future Labour government. More than that—May’s second administration, propped up by the DUP, is the most reactionary government Britain has seen since the inter-war years. But it is also weak and illegitimate. The protests demanding May’s resignation that started straight after the election need to continue on a much larger scale. She can be driven from office by a mass movement on the streets and in the workplaces that mobilises Labour Party members but goes well beyond them.

The aim of this movement has to be to force May from office. Logically, this implies demanding a second general election that can finish the job and bring Corbyn to 10 Downing Street. But the closer he gets to the premiership, the more he will face the extra-parliamentary powers of the state and capital. The lesson of the Syriza government in Greece is that these powers can only be defeated by an extra-parliamentary mass movement of the left—a movement in which revolutionary socialists have an essential part to play. The most important result of the election has been to lay the basis of this movement. Whatever the fate of Labour under Corbyn, we are participating in a renewal and expansion of the radical left in Britain whose effects will be felt for many years to come.

Alex Callinicos is Professor of European Studies at King’s College London and editor of International Socialism

Notes

1 See Callinicos, 2015a and 2015b.

2 One of the many dents to conventional wisdom produced by the election was the discovery that the main constitutional reform of the Conservative-Liberal Coalition government, the Fixed-Term Parliaments Act 2011, has not, as intended, removed the prime minister’s power to call snap elections, if the opposition parties cooperate in providing the necessary two thirds majority in the House of Commons to override the Act—as in this case, the fear of being seen to refuse to go to the electorate is a strong incentive to cooperate.

3 Davies, 2016.

4 For the American case, see Callinicos, 2017, pp4-14.

5 Runciman, 2017.

6 Ganesh, 2017.

7 Ford and Goodwin, 2014.

8 Moore, 2016.

9 Curtice, 2017.

10 Emmott, 2017.

11 Roberts, Marcus, 2017.

12 Wheatley, 2017.

13 Wheatley, 2017.

14 Toynbee, 2017.

15 Curtis, 2017.

16 Khan, 2017.

17 Goodwin, 2017.

18 Phillips and Webber, 2014.

19 https://twitter.com/FraserNelson/status/875095316235788288

20 Taylor, 1970, p269.

21 BBC News, 2017.

22 Powell, 2017.

23 Giles, 2017.

24 For an insider’s account of the EU’s demolition of Syriza see Varoufakis, 2017.

25 Münchau, 2017.

26 For a snapshot of the economic problems facing British capitalism, see Roberts, Michael, 2017.

27 Merrick, 2017.

28 For a classic analysis, see Cliff and Gluckstein, 1988.

References