On 26 July 2022, it will be 50 years since an upsurge of unofficial strikes freed five dockers from Pentonville Prison. Through this action striking workers won what Tony Cliff, founder of the International Socialist tradition associated with this journal, described as “the greatest victory for the British working class for more than half a century”.1 When we consider that there has since been what political economist Jane Hardy calls “a transition from a high to an historically very low level of strike activity”, the triumph at Pentonville seems even more historic.2

Yet, strangely this is a victory that is rarely mentioned, let alone seriously discussed.3 Moreover, we can confidently predict that the media will treat the 50th anniversary as a non-event.4 In this article we remember and celebrate the Pentonville victory, but we also want to do more than that. As rank and file London dockers in 1972, we want to double down on Cliff’s verdict that, “during the five-day struggle, the rank and file showed itself in all its glory, while the union bureaucracy…showed their complete bankruptcy”.5 Furthermore, we want to record some of the political dynamics of those five days and their build-up. Ultimately, our aim is to re-affirm that “the lessons of Pentonville are essentially revolutionary”.6

The battle lines are drawn

To understand the historic significance of the Pentonville victory it is necessary to understand the forces that confronted each other during the long hot summer of 1972. On one side was the new Conservative Party government under Edward Heath. The Tories had won a surprise victory in the June 1970 election on the promise of introducing laws to legally neuter the organised working class. Their manifesto spelt this out quite bluntly:

There have been more strikes in 1969 than ever before in our history… We aim to strengthen the unions and their official leadership by providing some deterrent against irresponsible action by unofficial minorities.7

A subsequent election manifesto explained what was at stake for the Tories and their class: “Remember the conventional wisdom of the day: we were in the grip of an incurable British disease. Britain was heading for irreversible decline”.8 Jane Hardy summarises the dynamics of the Tory counter-offensive:

On the election of a Conservative government in 1970, trade unions and workers faced a prime minister…whose mission was to be even tougher on the working class. He took up the baton from the previous Labour government, which had been forced to abandon its legislation designed to shackle trade unions and destroy shop stewards’ organisation in the face of a mounting strike wave at the end of 1969. The nakedly anti-union Industrial Relations Act…was a clumsy piece of legislation that quickly brought the state into conflict with workers.9

So, for the ruling class and their preferred party, the stakes were very high indeed. The Industrial Relations Act was drafted as a bill and introduced in parliament within weeks of Heath taking office. It passed through the various stages of the parliamentary line dance at speed, receiving royal assent in March 1971. It was the keystone legislation of Heath’s government, addressing what was seen as the central problem facing British capitalism.10

To get a sense of the forces on the other side of the battlelines in 1972 we must pass through the looking glass and peer back into an industrial ecosphere that has now (sadly) long disappeared. Like Hardy, we reject the pervasive sort of pessimism that argues that today’s workers have been bought off, split up and worn down into a catatonic state of powerlessness. However, it is obvious that working-class organisation, confidence and combativity were all much stronger 50 years ago than they are in the present day. Moreover, it would be reasonable to say that the registered dock workforce was among the best organised, most self-confident and most militant sections of Britain’s working class in 1972.

Dockers in “registered” ports were employed (or “registered”) under the National Dock Labour Scheme. The dockers in the ports managed under the Scheme were technically employed not by the companies for which they worked, but instead registered with local Dock Labour Boards. Half of each board was made up of trade union representatives. This system was a long way from any form of “workers’ control”, but it did assure a high level of job security. Employers in the ports simply did not have the usual seigneurial power over hiring and firing that they exercised in other parts of the economy. This meant, for example, that workers injured on the job—in what was a frighteningly dangerous working environment—could not just be sacked.11 On top of this, the registered ports were 100 percent pre-entry union “closed shops”. Any “newie” in the docks had to be a union member before they could even start work in the industry.12

There is no need to romanticise any of this. Dock work was hard and dangerous. Until 1970 it was still often a hybrid form of casual labour. Harry Constable, a prominent militant in the 1950s docks, explained:

The Dock Labour Scheme was in the nature of a legislated class compromise, an attempt to remove the class struggle without removing its causes. It was part of the…welfare state provisions that capitalism had been forced to grant rather than lose everything.13

Nonetheless, the upshot of working under the Scheme was that registered dockers had a very tight union organisation and a strong tradition of solidarity.14

However, throughout the post-war period, the majority dock union, the Transport and General Workers’ Union (TGWU), was in the grip of hard-nosed and frequently corrupt right-wing bureaucrats.15 Indeed, until 1968, the TGWU had a ban on any member of the Communist Party holding office in the union.16 Ralph Darlington and Dave Lyddon explain that this “led to workplace union organisation that was totally unofficial”. In most unionised industries there was a system of “shop steward” organisation that developed through the 1950s and 1960s. Stewards were shopfloor representatives, directly elected by the workforce, but they were usually recognised by both the official union and the employers. The Industrial Relations Act was a direct attempt to asphyxiate the shop steward system, reacting to the challenge described by Tony Cliff and Colin Barker:

Who leads the struggle at plant level for improved pay and conditions? Who acts as the main organiser of the unofficial movement? Who spearheads the…wage drive strike? Who really worries the management? Above all the shop stewards’ committees.17

The shop steward system was only introduced in the docks industry as late as 1970. Instead, before this, in the major ports—especially London, Liverpool and Hull—there were even more democratic forms of organisation. Each of the ports had its own form of unofficial organisation and a tradition of organising outside and, if necessary, in opposition to the union machine. In London, this took the form of the Liaison Committee, which reflected a now almost forgotten type of open mass democracy. Members of the Liaison Committee were elected at mass meetings where anyone could stand up and everyone could vote; members could also be removed in the same way. In the event of a dispute in the docks, the Liaison Committee would go from ship to ship, summoning dockers to an open air mass meeting where decisions were, again, made in the most democratic way: free and often angry discussion followed by a show of hands. When the shop stewards’ system was formalised in the docks in 1970, this form of mass democracy carried on alongside it.

There is another aspect of this unofficial political tradition in the docks that was subtly influential in July 1972. The culture of unofficial organisation and political discussion in the docks tended to be a good recruiting ground for the Communist Party (CP). However, there were a few brave dockers who broke with the CP and moved to the left. At a time when the Trotskyist movement in Britain was miniscule and largely disconnected from militant sections of the working class, there were nonetheless small but influential groups of Trotskyist dockers in all the major ports.18

Finally, the fighting mood in the docks reflected the rising combativity among the wider working class. The victory at Pentonville did not come out of nowhere. There was a very widespread understanding that the Industrial Relations Act was class legislation, threatening the job security and union organisation of all workers. During the parliamentary progression of the bill, there had been a campaign of marches and one-day strikes. More generally, there had been a turnaround in working class confidence since the defeat of the postal workers in 1970. The workers’ occupation at the Upper Clyde Shipbuilders in the summer of 1971 was followed by the knockout victory of the miners’ strike in early 1972, which climaxed in the mass picket of Saltley Gate. As Darlington and Lyddon put it, Pentonville was just the crescendo of what was a “glorious summer” for the working class.

So, in 1972, the 65,000 registered dockers were tightly organised. We had a long tradition of solidarity, and there was a network of respected and confident militants who were quite willing to take unofficial strike action. Yet, we were also facing an existential crisis of our own.

The casus belli

Containers had been first developed by the United States Army during the Second World War, but it was in the 1960s that the “container revolution” unfolded. The result was a dramatic undermining of the job security of dockers.19 The labour historian Peter Cole explains: “From the 1960s into the 1980s, containerisation expanded trade by an order of magnitude, dramatically increased productivity, sent the number of dockworkers plummeting and increased employers’ profits”.20 It was during the late 1960s and early 1970s that the container revolution hit the British docks industry—and it hit hard. We will focus on how this played out in the Port of London, but the pattern was similar in all the major registered ports.

Before the introduction of “unit loads”—first pallets and then containers—all cargo coming into or leaving Britain had to be moved by dockers by hand. Although containers were overwhelmingly still passing through registered ports, the “stuffing and stripping” of these containers could now be done outside the dock estates.21 Inland container depots began to spring up throughout East London, and port employers saw their chance to reduce their workforce. Under the National Dock Labour Scheme registered dockers could not actually be sacked, so instead they were placed in a state of limbo called the “temporary unattached register”. Job losses reached a crisis point when the Southern Stevedores docking company closed in early 1972.

The TGWU responded with its usual lethargy, but a network of unofficial militants loosely organised in the National Port Shop Stewards Committee took up the challenge and began a nationwide campaign of picketing and “blacking”—the practice of refusing to handle certain goods. Once again, describing this campaign involves time travel into a world of class struggle that will be hard to imagine today. First, dockers threw up picket lines across the entrance to the Chobham Farm inland container depot in Stratford, East London.22 As lorry drivers approached the picket line, they were given a simple ultimatum; if they crossed the line their haulage company would be blacked in the registered docks—we would refuse to service their lorries. In the docks, a “Cherry Blossom” list of scab firms would be published every few days, and dockers would simply refuse to load or discharge their lorries until they stopped crossing our picket lines.23

At this point, the campaign was mainly organised outside the TGWU bureaucracy, and all of the important decisions were put to an open vote at regular mass meetings. However, the compromising inertia of the TGWU was still a factor in the campaign, not least because many of the lorry drivers were themselves TGWU members, and soon the union would recruit the Chobham Farm labour force as well. These conflicting loyalties produced some viciously angry divisions among the London shop stewards with the CP-influenced leadership leaning towards the TGWU call for “moderation”, while other more militant stewards wanted to expand and intensify the campaign.

Nevertheless, this national campaign of picketing and blacking was exactly the kind of wildcat action that the Industrial Relations Act was designed to prevent. So, throughout the spring of 1972, the registered dockers inevitably moved closer and closer to a showdown with the Tory government and their new law.

There were early skirmishes in Liverpool over Heatons, a haulage company, and in Hull over Bishop’s Wharf, a small non-registered facility. These were resolved by TGWU retreat and compromise, but the conflict over Chobham Farm was more intractable. Chobham Farm was in many respects a full dress rehearsal for the smackdown that would soon follow at Midland Cold Store. The large container depot of Chobham Farm, just five miles from the Royal Docks, was partially owned by Tom Wallis, one of the major stevedoring companies in London, and it was clearly syphoning off what had traditionally been registered dock work. It was therefore the first target for the campaign of picketing and blacking. Ultimately, the Tories were forced to threaten to apply the full force of their new law and the National Industrial Relations Court (NIRC) issued warrants for the arrest of three London docker shop stewards—Vic Turner, Bernie Steer and Alan Williams. The three were due to be arrested on the picket line at Chobham Farm on 16 June, but at the last minute the Tories and their court staged a humiliating climbdown via a medieval throwback called the “tipstaff”, an official at the High Court.24

Now, the eye of the storm passed to another inland container depot just a few miles from Chobham Farm—Midland Cold Store. There had been some rather low intensity picketing of the depot for a few weeks. It had been presented in the press as a local start-up firm threatened by the bullyboys from the docks. At exactly this moment, Socialist Worker journalist Laurie Flynn revealed that Midland Cold Store was wholly owned by the giant Vestey Organisation. In some respects, the Vestey Organisation was a template for the integrated conglomerates that dominate the world economy today. Lord Samuel Vestey, an Old Etonian and personal friend of the Queen, owned farms in Argentina and Australia; he owned the Blue Star Line; and he owned Dewhurst, the biggest chain of butchers in Britain.25 For dockers, what was more important was that Vestey also owned Southern Stevedores, which had so recently apparently gone out of business and sacked its registered labour force. One of the richest men in the country was using the efficiencies of containers to replace highly organised registered dockers with cheap non-union labour.

Once Socialist Worker had exposed this duplicity, Vestey went on the offensive. After consulting Special Branch, he hired Euro-Tec, a firm of private detectives. These spooks then stalked some of the dockers from the picket line to their homes. Vestey used the “evidence” gathered to go back to the NIRC in order to get another injunction for the imprisonment of dockers if they failed to lift the picketing and blacking campaign at Midland Cold Store. Initially, Vestey named seven dockers, but the final arrest warrant was for just five. The joke in the docks was that the hard-nosed Vestey Organisation traditionally took no prisoners—this time it was taking five.

Let battle commence

Up to this point in the summer of 1972, the government had shown a distinct reluctance to actually use the Industrial Relations Act, which they had expended so much political effort to pass. This time the Tories decided to go in hard, and four of the five dockers were arrested on the afternoon of Friday 21 July.26

The response in the docks was just as decisive. As soon as it was announced that the five workers were to be arrested, there was an immediate walkout at all the registered ports. There would be no secret ballots to approve the strike. Instead, the policy of “One in the dock, all out the dock!” had been approved repeatedly at mass meetings up and down docklands. It had long been the practice in the docks that, prior to any strike action, dockers would replace the beams and hatch-boards on a ship so that the vessel would be structurally safe on the open sea. However, on Friday 21 July 1972 nobody had time for that—it was an entirely spontaneous walkout. Even before the gates of Pentonville Prison shut behind the five workers, 65,000 dockers were on a spontaneous, indefinite and mainly unofficial strike.27 Because Britain was almost wholly dependent on shipping before the opening of the Channel Tunnel in 1994, all trade into and out of the country abruptly stopped in the course of an afternoon.

In a typical act of defiance three of the Pentonville Five—Conny Clancy, Derek Watkins and Tony Merrick—chose to be arrested on the picket line at Midland Cold Store. There were only a couple of hundred dockers and supporters on the picket line with them, but the political drive that would release the Pentonville Five was already emerging. First, Tony Delaney, one of the militant stewards from the Royal Docks, started shouting “picket the fucking prison”. Delaney was one of the stewards with an association to Trotskyism, and this political response would play a fundamental role in the victory. Second, Delaney and another Royal Docks steward, Micky Fenn, walked directly into a small printing works that was opposite Midland Cold Store and demanded (that really is the only word that fits) that the shop steward there call the workers out on immediate strike. Within minutes of the arrests, three crucial political tactics had been established: this dispute would be fought out on the streets, not in committee rooms; it would be driven by the demand for class solidarity; and it would be led by docks shop stewards and not by union bureaucrats and their placemen. This political strategy would humiliate the Tory government and spring the Pentonville Five in a matter of days, and we would argue that it constituted a form of revolutionary politics.

When socialists discuss the critical question of “leadership”, all too often it becomes a matter of programmes and demands that veer towards the abstract. In the case of the Pentonville victory, we can be much more concrete. Again, it is important to stress that much of this analysis applies to the experience in London, and there were variations in different ports. However, the fact that the Five were all London dockers, combined with Delaney’s moment of inspiration about picketing the prison, meant that it would be the London shop stewards who were playing at home and driving the movement. This meant the political composition of the London shop stewards’ committee was central to the course of the dispute. In normal circumstances the extent of the influence of the CP would guarantee that it won most arguments, but here the CP was facing in two directions at the same time. On the one hand, they felt the pressure of the anger among ordinary dockers; on the other hand, their organisation was totally compromised by its strategy of a “left alliance” with leftist union officials such as Hugh Scanlon and Jack Jones.28 So, for example, it was the influence of the CP that limited the campaign of picketing and blacking to minimise the political inconvenience to Jones.29

Two of the Five—Bernie Steer and Vic Turner—were CP members, though Turner was no slavish follower of the party line. Of course, Steer and Turner had been taken out of the equation by being virtue of being stuck behind bars. Another respected CP steward was inconveniently on family holiday for the duration of the action. The most senior CP steward outside prison, Danny Lyons, would destroy what influence he might have had by turning up on the first night at Pentonville drunk and baying that only Steers and Turner “mattered” and the other three dockers were just “fodder”.30 That left the direction of the dispute in the hands of the non-CP stewards, and it was the most militant and determined of these (mainly younger) shop stewards who choreographed the victory. All of them were mistrustful of the TGWU machine and particularly Jack “The Rat” Jones—they had bitter experience of their treachery in a failed nine-week strike of 1967. Some, such as Delaney, had some involvement in Trotskyist politics; others, such as Fenn, had dropped out of the CP and moved to the left. Although it would be delusional to exaggerate the significance of this, it is notable that all of them—without exception—were regular readers of Socialist Worker, the weekly paper of the International Socialists (later the Socialist Workers Party).31

As pickets assembled in the pouring rain outside the forbidding walls of Pentonville Prison on that first Friday night, the stewards faced a massive political challenge—how could they take on and defeat a government with a 30-seat majority with the full force of the state behind it? There were a few more everyday problems added to this. As we have mentioned, there was an acceptance that the key to victory was working class solidarity in action. However, many of the best organised sections of the working class—such as car workers, engineers and some miners—were on summer holidays. Moreover, there was an even more basic problem: the weekend. How was it possible to generate any sense of momentum when most workers in 1972 would be on their free time?

The first strategic political decision was to make an appeal to the one group of well organised workers who most certainly would be working—the various print workers on Fleet Street. What happened on two successive nights there is a major lesson in itself. On the Friday night, several carloads of stewards drove the few miles to Fleet Street in search of solidarity action. They walked into the various newspapers and demanded to see the union reps and that they call mass meetings to vote for immediate strike action in solidarity with the Five. We were personally not part of these delegations, but it is clear that the stewards were met with a mixed response. A lot of sympathy was expressed, but all of the national newspapers printed as usual on that Friday night.

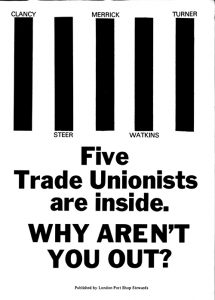

This snub might have demoralised a less determined leadership, but the dock stewards decided to return to Fleet Street on the Saturday night, and this time they were much better prepared. Whereas on Friday the delegation was restricted to a handful of shop stewards, on Saturday there was a general call for all supporters of the Five to assemble in Fleet Street, and thousands turned out. Whereas on Friday the dockers had approached printers as outsiders, on Saturday the delegations included respected print militants such as Mike Hicks, Vincent Flynn and Ross Pritchard. Whereas on Friday the stewards relied merely on the persuasive power of class solidarity, on Saturday this was reinforced by a loudspeaker van. Another important addition to the class fire power was the simple but brilliantly defiant leaflet shown in figure 1.

The leaflet was designed by Micky Fenn in the streets outside Pentonville in the immediate wake of the disappointment after that first visit to Fleet Street.32 The design was approved by other stewards, and Fenn then approached one of us to arrange for the printshop of the International Socialists (IS) at Cotton’s Gardens, East London, to print the leaflet. After late-night phone calls to Cliff and Roger Protz, then editor of Socialist Worker, it was agreed that one of the IS printworkers, Ross Pritchard, would work through the night to print tens of thousands of copies of the leaflet. Over the next four days, several hundred thousand more would be printed and distributed, and the imagery was also blown up to make a poster.33

Figure 1: Leaflet designed by Micky Fenn

There is some film footage of that Saturday night in Fleet Street, shot by the agitprop filmmakers from Cinema Action, which shows dockers, printers and their supporters proceeding down Fleet Street in a carnivalesque march that brought every single one of the newspapers out on strike.34 Where the politics of persuasion had failed on Friday, the politics of mass action stopped Fleet Street on Saturday.

This success became the playbook that was followed over the next four intoxicating days. This is a story that has been told elsewhere so we will focus on the political strategy rather than the amazing stories.35 The picket of the jail was maintained night and day, and the streets outside Pentonville Prison were a combination of demonstration and festival. The noise from the crowds was so loud and so persistent that some prisoners approached Tony Merrick and asked him if he could get his supporters to keep the noise down so they could get some sleep. Every day, as the numbers taking action swelled, delegations would march up the Caledonian Road, usually behind handmade banners. On Tuesday 25 July, there was a more formal mass march from Tower Hill to the prison.

The streets outside the prison walls were ground zero for the organisation of the campaign. This is where decisions were made, plans laid, and action plans handed out. From the very beginning, on the Friday night, the emphasis was on mass action and taking the fight to the class enemy. In other words, the campaign was guided by a clear political strategy and class politics.

An example of this was the mass flyposting that was organised on the Sunday night. Dozens and dozens of carloads were dispatched from Pentonville to plaster London with the message “Free the Five!”. Some of this was deliberately targeted against our political enemies—we hit the offices of the Confederation of British Industry, the Conservative Party head office in Westminster and the National Association of Port Employers. The Vestey Organisation and its high profile Dewhurst shops were also redecorated. Delegations were also sent to the headquarters of fascist organisations such as the National Front and the League of Empire Loyalists and even to Buckingham Palace. There was also more general flyposting that night—the idea was that, when they made their way to work on the Monday morning, workers should be only too aware that the fight to free the Five was alive and kicking.

The main strategy during these five days was to drive home the message of Fenn’s leaflet: “Why Aren’t You Out?” Wherever dockers could find an invitation from a group of workers, and sometimes even without one, the tactic was always the same: demand (still the right word) that a mass meeting be called and argue at that meeting that, when faced with an attack on our class, the only proportionate response is strike action. Most of these invitations would come through politically committed militants, but all the dockers on the picket outside Pentonville would find themselves speaking at meetings and demanding action. Darlington and Lyddon recount one story that is noteworthy only because it was so typical:

Sometime on Monday afternoon, the stewards decided there was a significant workplace that we had omitted—Heathrow Airport. So, I was dispatched with another docker and an IS engineering worker. The three of us drove into Heathrow, contemptuous of all the security guards. We drove up to Terminal One, demanded to see their convenor and two hours later there were no holiday flights from Heathrow due to action by the ground staff. This is the sheer sense of adrenaline when a class is on the move.36

It is difficult to get a clear picture of the numbers eventually involved in action to free the five dockers—partly because there were no newspapers to record this. However, Darlington and Lyddon suggest that, in addition to the 65,000 dockers who walked out on the Friday, there were another 90,000 workers on indefinite and usually unofficial strike. On top of this, “as many as a quarter of a million” workers took some form of more limited strike action. It should also be remembered that the strike action was swelling rather than deflating when the Five were released on Wednesday afternoon.37 For example, there was a meeting that day of 300 workplace delegates in the Hull area to call an all-out strike from the following day.38

So far, this article has only concentrated on the leadership of the campaign from street level, but there were, of course, other political forces contending over the direction of the strike. At the intermediate level, some of the older, “moderate” London shop stewards set themselves up in the offices of Newham North East Labour Party. There is no reason to doubt that all these dockers wanted to free the Five; their problem was that they could only imagine this happening through the official channels of the union machine. Their influence on the campaign was next to nothing, but that might have changed had the Tories not given in so quickly. At a more elevated level, the role of the Labour Party was despicable—even for a party that specialises in class betrayal. Reg Prentice, then shadow employment spokesperson and incredibly also a TGWU-sponsored MP, did everything he could to support the Tory government and to undermine the campaign to free the Five. He was quoted as saying: “They are absolutely wrong to organise the picketing and blacking and even more wrong to defy the order of the court… I have no sympathy for them, and I don’t think they deserve the support of other workers”.39

However, the main contender to dictate the strategy of the campaign inevitably emerged from the official trade union machines. Here, there was a contemporarily important, if ultimately historically trivial, difference between the left and the right of union officialdom. The right, typified by Vic Feather, the general secretary of the Trades Union Congress (TUC), more or less openly sided with the Tories and poured contempt on the dockers’ campaign. The left-wing union leaders were of a different order and might easily have snatched defeat from the jaws of victory. One aspect of the Pentonville victory that is always overlooked is that not one of the men most responsible for this victory were in the many jubilant photos from the afternoon the Five were freed. None of the political leaders that won the campaign was present to celebrate its moment of triumph, because they were all utterly exhausted. After five relentless days and nights, once the news broke that the Five would be freed, they went home to sleep. Indeed, it seems quite obvious to us that had the dispute lasted for even a day or two more, the political leadership would have probably been commandeered by the left wing of the union bureaucracy.40 The key to that political hijack would have been the “general strike” that the TUC had called for Monday 31 July.41 As Socialist Worker said at the time: “The union bureaucrats are jumping on the bandwagon—but only to apply the brakes.”

It is a commonplace for labour historians with a right-leaning slant to argue that it was the threat of the TUC strike that won the release of the Pentonville Five. Yet, in reality, the TUC only called this strike as a political gambit. Darlington and Lyddon produce strong evidence that the vote at the TUC general council was taken after it had been confirmed that the Tories were running up the white flag. Jack Jones admitted as much in an interview: “We moved what you call a general strike in the knowledge that it wouldn’t be necessary”.42

However, we do not need to speculate about what might have happened had the political leadership of the Pentonville campaign been grabbed by Jones and the left union bureaucrats. There is hard evidence of what would have occurred. Amid the euphoria of the victory on 26 July, the TGWU docks delegates’ conference voted just one day later for an indefinite, national docks strike starting the very next day in order to resolve the issue of the threat posed by containerisation. For political reasons the CP-influenced moderate shop stewards asserted themselves and the strike was left to be run entirely by the union machine.

This undermined one of the most significant features of the whole campaign that climaxed at Pentonville: the level of active involvement it encouraged. The mass meetings that set the general strategy were always enormous and invariably very lively. The picketing of the container depots was usually organised on a rota basis, and clusters of gangs were assigned sessions to maintain the picket line. The “Cherry Blossom” list could only work if all dockers were actively enforcing it. The picket of the prison actively involved thousands, and often tens of thousands of dockers from across the country. Many of those pickets would then be organised to speak at meetings, flypost and hand out leaflets. The victory at Pentonville was won by mass action and mass involvement by rank and file dockers. The official strike was the exact opposite, encouraged by the CP’s line that dockers could rely on the TGWU with their “left-wing” champion Jack Jones at its head. After the activism of the five days and its build-up, the official strike was passive to the point of inertia. Such was the level of union solidarity in the docks that no pickets were really necessary; there were no marches and we cannot recall a single mass meeting during the three weeks we were on strike.43

In the glorious summer of 1972, dockers took their chance to get on with their gardening or perhaps some DIY. Only after three weeks of this passivity, once Jones had reneged on his promises and the strike had been sold down the river, did the shop stewards change gear and call on dockers to take action against the TGWU sell-out. It was too little too late. Much of the active enthusiasm of Pentonville had been dissipated. At this point the shop stewards were easily out-manoeuvered by Jones and his placemen.44 The result was a particularly squalid compromise—the Jones-Aldington Report. Cliff rather inelegantly said of this report that “dockers got sweet Fanny Adams out of it”.45 Jones agreed to major job losses in return for higher severance payments. As always, Jack “The Rat” haggled over price rather than principle.

The central argument of this article is that Pentonville was indeed a historic victory but one achieved because our side was led by a group of politically conscious, highly determined shop stewards who gave zero fucks for legality and respectability. In simple but accurate terms, in our opinion, they acted like revolutionaries. The “question of leadership” has been one of the recurring memes of the Trotskyist movement, but it can become a form of ahistorical “what-iffery”, all the way back to “what might have happened if Spartacus had marched on Rome instead of heading south?” For once history spared us that torment—the movement to free the Pentonville Five got the political leadership it needed. Therefore, we won.

We mentioned above that none of the leaders of the strike were present at the prison when the Five were set free. However, they did get their moment to celebrate the victory. The following evening there was a victory meeting called by the International Socialists at a euphoric and packed Stratford Town Hall. Three of the imprisoned Five spoke from the platform (Clancy, Merrick and Watkins), and all of the docks shop stewards who had driven the victory spoke from the floor. The headline speaker was Tony Cliff.

Bob Light and Eddie Prevost were both London dockers working first in the Royal Group of Docks and then Tilbury. Prevost started in 1960 and Light in 1970. They were illegally sacked in July 1989 after the sell-out of the national dock strike. Both are members of the Socialist Workers Party.

Notes

1 Cliff, 2002, p329.

2 Hardy, 2021, p70.

3 By far the best written discussion of Pentonville is chapter five of Ralph Darlington and Dave Lyddon’s Glorious Summer: Class Struggle in Britain 1972. The book has a cover photo of Vic Turner, one of the Five being crowd-surfed after his release. See also Fred Lindop’s articles in the journal Historical Studies in Industrial Relations (edited by Dave Lyddon)—Lindop, 1998a and 1998b.

4 In the past 18 months, two of the Pentonville Five—Tony Merrick and Derek Watkins—sadly died, yet none of the “liberal” press bothered to commemorate their achievement.

5 Cliff, 2002, p333.

6 Darlington and Lyddon, 2001, p229. Full disclosure—this quote actually comes from one of us. It is worth adding that this is a contested opinion. For instance, Fred Lindop argues that Pentonville was never a revolutionary moment but instead represented “the very best of the militant syndicalism of the post-war period”.

8 From the Conservative Party’s 1987 election manifesto—www.conservativemanifesto.com/1987/1987-conservative-manifesto.shtml

9 Hardy, 2021, p74.

10 Hardy, 2021, p74.

11 During these years, dock work had the second worst record for industrial accidents and significantly more deaths and serious injuries per thousand workers than, for example, coal mining. Only trawler fishers worked in more dangerous conditions.

12 When there was a recruitment into the docks, the port employers could nominate up to 50 percent of the intake. In practice, even these men had to have union credentials. For a variety of reasons, and with a pleasing irony, the employers’ nominees often turned out to be the foremost militants—Micky Fenn, discussed below, was one.

13 Hunter, 2017, p116.

14 You can see a list of dockers’ class battle honours in Cliff, 2002, p379.

15 In 1972 there were still two unions in the docks: the massive TGWU and the National Amalgamated Stevedores and Dockers Union (NAS&DU). The two unions were usually referred to as the Whites and the Blues, names derived from the respective colours of their union cards. Three of the Pentonville Five were NAS&DU members—Bernie Steer, Conny Clancy and Derek Watkins. The NAS&DU was much more democratic than the TGWU, and it was frequently more militant, actually calling its members out on official strike over the arrest of the Five. However, the Blues were mostly restricted to organising in London and by 1972 they probably had no more than 6,000 members. Moreover, in the mid-1950s, an attempt by dockers influenced by the Socialist Labour League to use the NAS&DU as a breakaway union to undermine the TGWU resulted in a vicious turf war, especially in Liverpool and Hull, leaving a lasting legacy of hostility towards the Blues. In 1959, the NAS&DU was officially expelled from the Trades Union Congress. The upshot was that the NAS&DU played an honourable but marginal role in 1972.

16 In the early 1970s, the Communist Party was still the largest political party to the left of Labour. Although the party’s membership had slumped from its post-war high of 60,000 to around 30,000 by 1972, it continued to claim the loyalties of a significant number of industrial militants.

17 Cliff, 2002, p79.

18 In London there was Harry Constable and later Terry Barrett. In Liverpool, Larry Kavanagh, Tony Burke and Peter Kerrigan, and in Hull, Roy Garmston.

19 See www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v43/n08/john-lanchester/gargantuanisation for a more complete discussion of the role of containerisation in the expansion of world trade.

20 Cole, 2018, p2.

21 The Port of Felixstowe would eventually become the largest port in Britain, but it was still a rural backwater in the 1960s and 1970s.

22 Today, much of this area has been built over by the Westfield shopping centre. In 1972, however, this part of Stratford was still a busy industrial area.

23 This name typifies the two-faced approach of the TGWU Docks Group machine. Cherry Blossom was the most common brand of shoe polish in the 1970s, so the name implied “blacking” without actually using the term. This euphemism gave the TGWU some “plausible deniability” in the face of a law that they pretended not to recognise.

24 The Tories used the legal fig leaf of an intervention by the Official Solicitor who sent the tipstaff (a position created in the 14th century and rarely used since then) to inform Turner, Steer and Williams.

25 In 1940, the Vesteys were officially the richest family in Britain, second only to the monarch. In the 1980s, to nobody’s great surprise, it was revealed that the company had employed tax avoidance strategies and paid derisory amounts of tax throughout these years.

26 Despite his arrest being ordered at the same time, Vic Turner was only actually detained the following day on the picket line outside Pentonville Prison.

27 As noted above, technically dockers who were members of the minority NAS&DU were on official strike.

28 Jack Jones was the general secretary of the TGWU, then Britain’s largest union, and Hugh Scanlon was the general secretary of the Amalgamated Union of Engineering Workers. Both were the product of the Broad Left factions in their respective unions and were identified with the left-wing voices in the TUC. In the broadsheet newspapers they were unaffectionately known as the “terrible twins”. For a more extensive explanation, see Darlington and Lyddon, 2001.

29 Militant stewards wanted to picket the London International Freight Terminal in Stratford, which was by far the biggest inland container facility. There were bitter disagreements about this.

30 One of us can verify this incident, along with the outrage it caused, as an eyewitness. Lyons did not show his face at the prison again.

31 One of the authors of this article and Fred Lindop would regularly sell the paper to all of them. Colin Ross, in particular, gave several in-depth interviews to Socialist Worker in the build-up to Pentonville.

32 In personal correspondence Fred Lindop adds: “The leaflet was Micky’s inspiration, but Laurie Flynn turned it into the final effective design. I was there and saw it done on the back of an empty cigarette packet. The original has no printer’s name, thus avoiding giving any angle to the CP.”

33 There was another iconic poster produced during Pentonville by printworkers who were occupying the Briant Colour Printing printworks in the Old Kent Road in order to fight against redundancies.

34 This can be seen in a Cinema Action film about Pentonville, Arise Ye Workers, which is available online—www.youtube.com/watch?v=qQGnKf58fkg. This film is well worth watching as cinéma vérité footage of the five days, but it is also heavily skewed towards the milquetoast politics of the CP and is mainly taken up with a boring interview with Bernie Steers (who, of course, played a purely passive role in the five days due to being in prison). We showed the Cinema Action movie at a conference of The Dockworker in 1973, and there was a great deal of loud anger expressed towards the CP-compliant politics of the film.

35 See chapter 5 of Darlington and Lyddon, 2001. There is also an audio file of interviews (with printouts) conducted by Fred Lindop with dockworkers about 1972 available at the University of Warwick website. This covers all the major docks, includes most of the leading activists in the major ports (only Bernie Steers refused to be interviewed), plus many trade union officials (including Jones but not Scanlon, who refused), employers in Liverpool and Hull (but not London), and several Tory politicians.

36 Darlington and Lyddon, 2001, p166-167.

37 In personal correspondence, Sheila McGregor makes the important point that socialists up and down Britain threw themselves into the campaign to free the Five: “IS comrades across the country postered in support of the dockers, contacted shop stewards and so on. Those five days were hectic for all of us. We were small, but we acted as revolutionaries.”

38 Darlington and Lyddon, 2001, p167. Fred Lindop comments (in personal correspondence): “On the numbers on strike, Darlington and Lyddon’ figures and comments are reliable, based on my article. I spent a fair bit of time at British Library in Colindale reading the provincial press from the major conurbations. The TUC General Council move (backed by the CP) definitely stopped the movement. Some groups of workers had voted for all-out strike after the weekend: for example, Hawker Siddeley in Hull and Cammell Laird in Birkenhead.”

39 Darlington and Lyddon, 2001, p169. Prentice was subsequently deselected by his constituency party and “crossed the floor” to join Margaret Thatcher’s Conservatives. However, it should also be noted that, in the votes for the Labour shadow cabinet in 1973, Prentice topped the poll.

40 This is of course one of the most compelling reasons why the IS and its successor, the Socialist Workers Party, placed such emphasis on the need for a revolutionary party. The Pentonville victory is an example of how a determined and politically-conscious group of stewards pulled off an historic victory; however, had the campaign been more elongated, the momentum could only have been sustained by a much larger network of militants acting under tight discipline.

41 Typically, the TUC refused to call this a “general strike”, instead branding it a “national stoppage”.

42 Darlington and Lyddon, 2001, p172.

43 At least this was true in 1972; as the downturn in militancy continued, scabbing in the docks became a problem even in the traditionally solid ports.

44 For example, the TGWU ensured that all the traditionally less militant ports held early meetings to confirm the return to work. By the time London, Liverpool and Hull held their meetings, the momentum was going in reverse, and workers who at this point had been on strike without pay for four weeks saw little chance of winning.

45 Cliff, 2002.

References