The issues that have driven the “trade union debate” in International Socialism are fundamental to the left in Britain and most importantly to Marxists. The “problem”, often repeated in this journal and elsewhere, is simply this: the level of strike action mounted by British workers has remained at a very low level for a very long time. If Marxists wish to maintain the historical potential of the working class to act as a social force in its own right, able not only to resist attacks from both employers and an ever more aggressive capitalist state, but ultimately to challenge the existence of capitalism, then this is something that must be explained.

Frequently, comrades in this debate (and myself particularly) have reluctantly cited the monotonously repeating messages from the “Labour disputes in the UK” reports—published retrospectively for each year in May by the Office for National Statistics (ONS)—that, once again, the figures are the “amongst the lowest” or even “are the lowest” since records began. The figures for the last complete annual data set (2018) were no exception.1 Responding once more to this reality, this article will restate the phenomenon of the extraordinarily low strike rate that began in the late 1980s and continues today.2 It will then summarise a model that explains this phenomenon—developed and refined through the challenges and responses of the debate—by identifying a change in the character of British trade unionism. However, it will not restate the trajectory of shifts in state policy spanning Conservative and Labour governments from the late 1960s onwards that has led to this change.3

The model will therefore be presented abstractly in order to convey the conjunction of factors and organisational responses that shape trade union behaviour today. It foregrounds the “objective risk” involved in taking strike action for both trade unions and individual workers. In this way, it is different from explanations centred primarily upon cultural or affective factors, such as the confidence of workers, or upon long-term economic trends.

The article also identifies a shift towards a type of trade unionism that I characterise as “legal unionism”. I argue that leaderships of both the right and the left are now largely wedded to this kind of trade unionism as an alternative to strike action.

Finally, this article reflects on the consequences of these changes for revolutionary practice in the trade unions—locating the major “fault-line” at the base of the trade unions and the potential for “rank and file” moments that can suddenly appear as a result at critical points within or in place of official strike action.

The problem

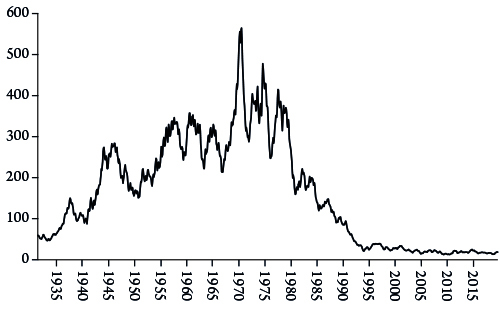

Figure 1 shows the number of work stoppages in any given year. It shows starkly the more than three-decades-long low in strike figures from the late 1980s to the present day. To emphasise the historical significance of this flat-lining effect, it is worth noting that the annual strike rate was greater during the Second World War—when strikes were illegal. The same 30-year-low is evident also if we consider other measures, such as “days lost to industry” and “numbers of workers involved”.4 Over this same period, we also see the ineffectiveness of trade unions measured by the decline in the “trade union premium”, the wage differential between organised and non-organised workers. Between 1995 and 2018 the premium fell from 15.3 percent to 2.6 percent in the private sector, 29.0 percent to 11.6 percent in the public sector, and 21.2 percent to 7.9 percent for all employees.5

Figure 1: Number of stoppages in progress, 7 month rolling average

Source: Calculated from ONS Labour Market Statistics

An explanatory model: risk and adaptations to risk

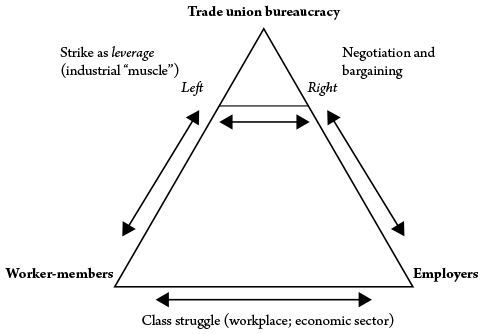

There are three types of interaction, or “axes”, that define the British trade union: that between workers and capitalist employers, that between trade union members and trade union officials (the “trade union bureaucracy”), and that between the left and the right of the trade union bureaucracy.6 At the risk of over-abstraction, we can summarise the situation visually to illustrate the dynamics of these interrelationships, and their associated vectors of force (figure 2).

Figure 2

To explain the low level of strikes over more than three decades we need to consider how the constituent elements of this schema interact today. There are three areas to bring into focus.

(1) Loss of legal immunity

The principle of legal immunity from actions by employers seeking damages from a trade union due to industrial action was enshrined in the Trade Disputes Act of 1906 and the Trade Disputes and Trade Unions Act of 1946. It was briefly lost in the July 1972 ruling by the National Industrial Relations Court (NIRC) that transferred liability for damages from individual members of a trade union to the trade union itself.7

The circumstance was the imprisonment of five dockers from the Newham Chobham Farm Docks at Pentonville Prison and their release. The NIRC, following an intervention by the Official Solicitor, used a precedent from a House of Lords ruling on a dispute in the North West of England, Heatons vs TGWU, to the effect that the dockers themselves were not liable for damages, only their union—which was deemed “vicariously liable”—so enabling their “lawful” release in order to avert a major confrontation with the unions. This episode was also the point on which the 1971 Industrial Relations Act, established to control the trade unions, shattered, with the Tory government of Edward Heath collapsing in the face of an imminent general strike called against a backdrop of a surging strike movement to release the five men.8 The principle of vicarious liability was dropped soon after the fall of the Tories in October 1974.9

However, “vicarious liability” found its way back into the statutes via the 1982 Employment Act, introduced by Margaret Thatcher’s Tory government, which aimed to reduce trade union power by stealth in successive acts, rather than all at once in a single act.

The trade union movement has been living with the implications of this legal principle ever since. It has created risk for unions when calling strikes, exposing them to court injunctions and potential claims by employers because of the legal transgressions of their members.10 One result has been the disappearance of the type of strike that, while unofficial (that is, not called or endorsed by national officials), is nonetheless tolerated and even covertly encouraged. Another has been a “bureaucratic intensification” as national officials strive to control more tightly membership behaviour in dispute situations.

(2) Loss of legal autonomy

Before the Tory governments of 1979-92, trade unions were self-organising bodies that determined their actions (including industrial action) by their own democratic methods. This changed with the employment acts of the 1980s and early 1990s.

Specifically these included: the 1980 Employment Act, which introduced controls on strike conduct and in particular restricted secondary action; the 1982 Employment Act, which enabled employers to seek damages where unions acted unlawfully; the 1984 Trade Union Act, which made balloting a condition of lawful industrial action and prevented unions paying fines incurred by their members; and the 1990 Employment Act, which required that a union repudiate unlawful action and allowed for the selective dismissal of strikers taking such action.11

The result of these changes has been new types of objective risk for ordinary trade union members, who are now unable to look to their union for protection should they be dismissed for breaking their employment contract outside of the protection of the law.12 The effect has been to make worker members of trade unions dependent upon their officials’ sanction if their action is to be lawful and thus relatively risk-free.13

(3) Gaining of “positive (legal) rights”

In the post-Thatcher era, under the John Major government of 1990-97 and the Tony Blair and Gordon Brown governments of 1997-2010, legislative elements began to appear that gave trade unions a degree of legal leverage over employers.14 These included: the 1992 Trade Unions and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act, which provided consultation rights to trade unions in redundancy situations; the 1999 Employment Relations Act, which created recognition and negotiation rights in workplaces with more than 21 employees; the 1999 Disability Rights Commission Act, which placed anti-discrimination requirements upon employers; the 2002 Employment Relations Act, which improved parental rights in the workplace; the 2008 Employment Act, which strengthened the enforcement of the National Minimum Wage; and the 2010 Equality Act, which legislated against harassment of workers with “protected characteristics” and created the “public sector equality duty”.15

The effect of this “positive workplace rights” agenda has been to create an alternative to striking for trade unions, now able to mount legal action against employers in a range of circumstances, so representing an alteration in the register of trade union behaviour away from industrial action as the primary resort. This new legislative platform was accompanied by “partnership agendas” in some sectors, partly supported by legislation such as the 2002 Employment Relations Act, which introduced statutory time off for trade union learning representatives.16

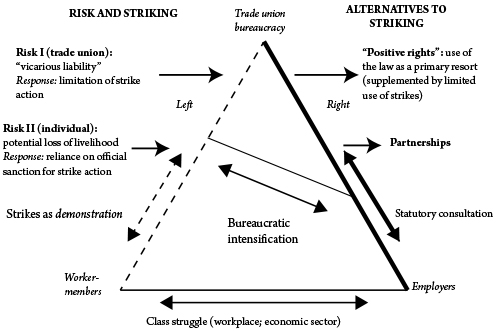

Our pyramid now looks like figure 3.17 It is crucial to note that these changes affect the left as well as the right within national leaderships. They are the result of structural alterations to how trade union behaviour is articulated within today’s socio-legal framework, and to how the structural relationships between workers, employers, trade unions and the state are now configured. The risks on the left hand side of our pyramid, for the trade union (Risk I) and for individuals (Risk II) are real. The shift towards legalism is a “rational response” to these risks—“rational” that is for trade union officials, wary now of creating situations in which events might run out of their control. It is, of course, not “rational” in the longer term for worker members who suffer the effects of inferior contracts, deteriorating working conditions and declining real terms wage levels. One indicator of this is the declining trade union premium, which we have already looked at.

Figure 3

Our revised diagram now shows a skewing of the trade union bureaucracy “to the right”, as a structural tendency, regardless that is of formal political orientations and rhetorical style. It represents an intensification of bureaucratic control of members’ behaviour, and a change in the mode of operation of the trade union bureaucracy itself. It furthermore marks a shift from the industrial unionism of a previous era to legal unionism, a new organisational form that today dominates industrial relations in Britain.

The “official lefts”

The political character of national leaderships still matters for trade union activists. Right-wing leaders at the national level typically create obstacles to official strike action. It is important to see left leaders achieving national influence. The stronger the left in a union, the better the prospects for it delivering strikes, even if they are of limited duration and effectiveness. However, we must acknowledge the changes that have occurred to the nature of British trade unionism, as well as the more obvious changes to the environment that unions operate within. These changes have weighted the scales heavily against strikes as an industrial response in national disputes.

Two illustrations will suffice here. First, we have the example of the left-wing Communication Workers Union (CWU) leadership that crumbled in the face of an employers’ injunction in November 2019, despite a vote of 97.1 percent (on a 75 percent turnout) for national strike action against the Royal Mail Group.18 The cause of the 2019 dispute was employer infringements of a comprehensive partnership deal, the “Four Pillars Agreement”, that the union had recommended to its members and signed up to in 2018. Second, there is the example of the Public and Commercial Services Union (PCS). The PCS, in the face of mass civil service redundancies from 2008 onwards, and especially in the wake of the 2010 government Comprehensive Spending Review, staged two days of strike action, followed by a legal campaign through the High Court in defence of the Civil Service Compensation Scheme.19 This was important of course, but not a proportionate industrial response, and not resistance to redundancies per se.20 The structural changes introduced by the era of legalism have led to the severe attenuation of the industrial (as opposed to simply political) left in the unions.

Moreover, the very meaning of the language of “left” and “right” in the unions has changed. “Left” no longer represents a consistent indicator of preference for industrial over legal routes to national dispute resolution. The pattern of industrial action, where it still occurs, does not fall straightforwardly along left-right lines. In particular, the left-led unions present a contradictory picture. On the one hand, the University and College Union has mounted impactful strikes in recent years and provided an example of what can still be achieved where a commitment to industrial unionism survives. On the other hand, we see left-led unions such as the CWU and the PCS not delivering substantial strike action when it is needed, or even when it is strongly mandated. All of this contrasts markedly with the British Airways Mixed Fleet cabin crews, members of the not-so-left unions British Airlines Pilots Association (BALPA) and Unite, who staged 86 days of strike action in 2017. The fact that significant industrial action can still occur reminds us that we are dealing here with tendencies, not pure phenomena or completed processes. However, these examples also suggest that political leaning at the top of the trade union is not the chief determinant of whether substantial strike action occurs.

An alternative

To conclude, there is an alternative scenario to consider which, given the change in the nature of British trade unionism I have discussed, seems likely. This is that accumulating grievances begin to break out in an uncontrolled manner, as walkouts triggered by local “final-straws”, and sudden worker actions that occur without official authorisation. Such rank and file moments happen when workers suddenly act outside of officially endorsed actions, pushing them up to and beyond their lawfully prescribed limits, or when the potential for this to happen presents itself as a result of: frustration with negotiations, defiance of court orders, solidarity with a victimised colleague, a serious safety issue, bitterness after a prolonged period of “strike suppression” and so on.21 These moments are located on the primary fault line running through British trade unionism: the contradiction of enormous working class grievance, anger and frustration on the one hand, and the restriction or avoidance of national industrial action by union leaders on the other. This tension lies at the base of the trade unions. When faced with spontaneous strikes, national officials (both left and right) are left on the wrong side of the dividing line between legal responsibility and working-class solidarity.

In each separate case in which workers step beyond officially endorsed limits to industrial action, there is also the germ of something bigger to come. A glance across the English Channel shows how collective action can erupt into life outside of the traditional structures, sweeping to one side official obsessions with “the law”, and legitimising legal transgression as it grows. A movement such as the gilets jaunes (“yellow vests”) in France involves trade union members in their many thousands, who take its energy and disregard of officialdom back into their organisations. Considering also the instabilities created by departure from the European Union, it seems more than possible that some variant of this can happen in Britain.

Questions naturally follow from this assessment. Are we positioning ourselves correctly for this kind of scenario? How can we use rank and file moments to build a culture of local and national solidarity? What is the structure of those rank-and-file moments? How can we anticipate and relate to them in practical terms? How do we support action that is unofficial? How do we reduce the significant risks involved? How will we support activists and spontaneous leaders who are victimised for leading action without the protection of the law? How do we use our official positions to build networks of locally rooted activists? What would a strategic practical orientation along these lines look like? And so on.

To help us answer these questions we should indeed look to France and the “yellow-vesting” of the trade unions there, where activists have built “a solid network of solidarities and friendships” in each local area.22

Such perspectives can help to orient our activism primarily at the base of trade unions; working systematically to unite moments of resistance in localities where—after more than 30 years of suffocating control of national industrial action—walkouts and even eruptive actions will occur regardless of the law and despite the very real risks that they entail.

Mark O’Brien is a socialist researcher based in the city of Liverpool.

Notes

1 The figures for 2018 in ONS, 2019a are the last complete data set. They show: the sixth-lowest annual total for “working days lost” due to labour disputes since records began in 1891; the lowest number of “working days lost” in the public sector since records began for public sector strikes in 1996; the second-lowest figure for the number of workers involved in strikes since records began in 1893; and the second-lowest figure for the total number of stoppages since records began in 1930. A single dispute, the University and College Union pension dispute, accounted for 61 percent of all strike days.

2 This article does not reply specifically to Dave Lyddon’s article in International Socialism 162. His critical points are noted and appreciated. I have great respect for Dave’s expert knowledge on this topic. However, my view is that further debate between Dave and I is of limited value and creates the appearance of a dispute between individuals—a type of continuous exchange more befitting of academic debate than revolutionary praxis. If the analysis that I have promoted is of more than academic interest, others will engage with it, either supportively or with further critique.

3 The historical aspect of the model presented here in elemental form is explained in O’Brien, 2018 and defended in O’Brien, 2019, responding to welcome challenges in Lyddon, 2018.

4 ONS, 2019b

5 ONS, 2019c

6 This characterisation draws on Cliff and Gluckstein, 1985.

7 The NIRC had been established by the 1971 Industrial Relations Act to provide the means by which the legal restraints upon the unions would be implemented. It fell into disuse soon after the Pentonville Five crisis.

8 Sewell, 2012.

9 This dispute concerned the blacking (refusal to handle) by Liverpool dockers of freight carried by St Helen’s based haulage company Heatons in April 1972.

10 This is “Risk I” in figure 3.

11 The 1992 Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act significantly strengthened the law on this point. The national executive, general secretary and/or president must write individually to workers using statutory wording to repudiate their unofficial action and must give the names of those individuals to their employer, if they are to avoid liabilities.

12 This is Risk II type in figure 3.

13 The risk of loss of employment is compounded by the removal of social protections for workers, and the prospects of the loss of one’s home, a fall into the low pay economy or into a vicious benefits system. I discuss this aspect of the problem in O’Brien, 2018. Also arising from this type of risk is the erosion of activist autonomy at the local level as branches become reliant on official sanction for action to go ahead. I discuss this issue in O’Brien, 2014.

14 These acts had precedents in the “Social Contract” era under the Labour governments of the 1970s, specifically the 1975 Employment Protection Act, the 1975 Sex Discrimination Act and the 1976 Race Relations Act. Along with the 1974 Trade Union and Labour Relations Act and the 1976 Trade Union and Labour Relations Amendment Act, they were part of the of legislative agenda that implemented the recommendations of the 1968 Donovan Report into trade union conduct. I discuss the role of Labour in government in shifts of state policy towards the unions in O’Brien, 2018.

15 Since 2010, with the arrival of the Conservative-led coalition government, these “positive workplace rights” have been weakened with successive rounds of legislation covering areas such as health and safety, employment tribunal rights and statutory consultation periods. Trade unions now have to defend these rights where they are threatened. The right to strike, of course, continues to be eroded with the 2016 Trade Union Act that sets restrictively high thresholds for ballot participation ahead of industrial action and the introduction of minimum service conditions for unions in the transport sector.

16 Also relevant here was the 2004 Warwick Agreement intended to achieve improvements on low pay, public sector pensions, job harmonisation in local government, and training and apprenticeships. The partnership element of the model I am proposing is discussed in O’Brien, 2015.

17 The historically weakened influence of the “worker members/trade union bureaucracy” axis is represented by the dotted line. The historically strengthened influence of the “trade union bureaucracy/employers and courts” axis is represented by the heavy line and also the skewing of the shape of the apex to the right. Strikes are still present, but now typically for demonstrative purposes only.

18 CWU members delivered similarly high votes for industrial action in previous years, most notably in 2017 with a vote of 89 percent for strike action over pensions, pay and jobs by 74 percent of members—see Syal, 2017. Despite these levels of membership support for strike action, the CWU failed to deliver on the strong mandates it achieved. As this article went to press, the CWU announced another stunning result following a re-ballot over the “Four Pillars” dispute and also over pay. The result was 94 percent in favour of strikes on a 63.4 percent turnout. This was followed by an announcement that no action would be taken until after the Covid-19 crisis. The CWU has an established culture of unofficial walkouts at the local level.

19 The strikes took place over the 8-9 March 2010. Other national days of action mounted by PCS for all of its sectors over this period have included: 30 June 2011 (pensions), 30 November 2011 (pensions), 10 May 2012 (pensions) and 10 July 2014 (pay).

20 The civil service workforce contracted by 106,814 (20.3 percent) between 2008 and 2016, from 525,157 to 418,343 (ONS, 2016). Numbers have since risen to former levels in response to the EU referendum result of 2016.

21 I discuss rank and file moments in more detail in O’Brien, 2019. For a more wide-ranging workers’ account of such potential triggers and stresses in the modern workplace more generally, see O’Brien and Kyprianou 2017, chapter 4.

22 ACTA, 2020.

References