The past has been

A mint of blood and sorrow –

That must not be

True of tomorrow. 1

From appeasement to coordinated strike action

Langston Hughes wrote the short poem “History” ,just as the US labour movement rose like a phoenix out of the ashes of the devastation of the Great Depression of the 1930s. Today Britain too is in the throes of an assault on the working class and the poor, the like of which we have not seen since the 1930s. Will it end in “blood or sorrow” or will we too see a sweet revenge? The half million strong Trades Union Congress demonstration against the cuts on 26 March 2011 marked a major turning point in that struggle. The process may have been slow, painful and one that is still fragile, but the organised working class has become a central player in the resistance to the government’s austerity measures. Mark Serwotka, the general secretary of the PCS, summed up the mood of many when he said, “We have marched for the alternative. Now we have to strike for the

alternative”.2 As I write this article, four major unions are set to strike to defend their pensions on 30 June. If these strikes go ahead, it opens up the possibility of wider and more militant struggles to follow.

But if you cast your mind back to last summer, the picture was far from rosy. The TUC made it clear that it was opposed to an autumn national demonstration against the government’s austerity measures, and not only that, it announced that David Cameron had been invited to address the TUC’s annual Congress in September. A spokesperson said: “The TUC’s general council gave overwhelming support for the invitation to the prime minister to address Congress. This was not to endorse his policies, but to ensure he addresses the concerns of people at work”.3 Many a union leader lined up to make it clear that they too opposed any talk of strikes and mass demonstrations. Derek Simpson, the then joint general secretary of Unite (Britain’s biggest union), told the BBC that talk of an “autumn of discontent” would only help the government by deflecting attention away from the spending cuts and their impact. “I don’t think that’s the nature of the British public,” he said. “We don’t have the volatile nature of the French or the Greeks”.4 The rejection of a general strike was not confined to the trade union leaders. The national steering committee of the Coalition of Resistance (CoR), one of the national anti-cuts organisations, voted down a motion calling for a general strike. Some officers of CoR claimed it would upset Unite.

But by the time the TUC leaders arrived at their conference in Manchester last September the “volatile nature” of the Greeks and French seemed to have infected the conference delegates. I wrote at the time:

I first attended a TUC conference in 1986 and have been going to them on and off ever since. Never before have I heard so such fighting talk. Talk of a national demonstration against the cuts and coordinated resistance has buoyed up many trade union activists. A massive protest next year could electrify the trade union movement and become the launch pad for militant action. September’s TUC shows that when the trade union bureaucracy gives even the slightest nod in the direction of resistance it can dramatically alter the mood of key sections of the working class.5

The reason for this dramatic shift was threefold. Clearly the scale of the cuts and the refusal of the government to enter meaningful talks gave the union leaders little space to manoeuvre and negotiate compromises. Also union leaders have always felt more comfortable resisting a Tory government than they do a Labour one. Secondly, by early autumn the pressure was building up from below. London firefighters organised very large and militant demonstrations in opposition to the cuts to their services, and joint strikes by rail workers belonging to the RMT and TSSA brought London to a grinding halt in September. Even workers at the BBC voted to take action against job losses. Lastly, during the summer of 2010, major divisions emerged inside the trade union bureaucracy. While union leaders like Simpson and Dave Prentis of Unison rejected out of hand any idea of a national demonstration, let alone strikes, others like Mark Serwotka (PCS) and Bob Crow (RMT) openly called for action. Fear of being outflanked by the smaller unions and of pressure inside their own unions forced the likes of Prentis and Simpson to support both the call for a national demonstration in the spring and the motion calling for coordinated action.

Two other movements outside the sphere of the “official” trade union movement also helped radicalise sections of the working class. First, as the cuts were unveiled a myriad of anti-cuts groups and protests grew up. Individual trade unionists played a key role in many of these. But it was the outburst of student militancy last winter that really showed how fragile the government was. The students smashed the idea that the cuts could not be resisted. Len McCluskey spoke for hundreds of thousands when he told the police at the 26 March demonstration to “keep your sleazy hands off our kids”. Most important of all, the student protest destroyed the myth that the government’s austerity measures were supported.

During March there were small signs of a growing militancy developing inside the working class. There was Day X, the protest that saw over a thousand student nurses and doctors take to the streets in London against the cuts in the NHS. This unofficial march was clearly inspired by the student protests. Then the University and College Union (UCU) took national strike action over pensions on 24 March 2011, and within days of the 26 March protest teachers in Camden, north London, and teachers and council workers in Tower Hamlets, east London, struck for the day against the cuts. Over 7,000 workers were involved. An interesting feature of the strikes was the spontaneous chanting for a general strike.6

The idea of a general strike was, in the run-up to and on the TUC demonstration on 26 March, a popular political slogan. Since then it has become a real possibility. Coordinated strikes set for 30 June and the possibility of further and more widespread action in the autumn mean that the working class is slowly nudging towards a major industrial confrontation with the government. It is no exaggeration to say that the trade union movement faces its biggest test since the miners’ strike of 1984-5. The defeats of the past two decades and the very low levels of class struggle mean that two factors are going to be critical to the outcome of any future struggles. The first will be the role of the trade union bureaucracy and the second the confidence and organisation of union members and the shop stewards and reps. I want to look first at the strengths and weaknesses of the trade union movement in Britain today.

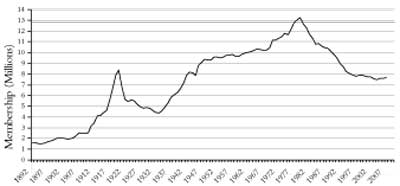

Figure 1: Trade union membership levels in UK from 1892 to 2009

Source: Labour Force Survey, ONS; Department for Employment (1892-1974); Certification Office (1974-2007/8)

A question of organisation

The first thing that strikes you when you look at figure 1 is the sharp decline in union membership during the 1980s. This is primarily due to two related factors. The first is the high levels of unemployment that stalked the country during most of the 1980s. Unemployment reached its highpoint of 3 million people (12 percent of the working population) in 1983.7 Industrial sectors like coal, steel and manufacturing were hit particularly hard; these bastions of the trade union movement were decimated. So even when the economy grew again, the growth often took place in sectors with little or no trade union organisation or tradition and therefore many unions did not even maintain their membership, let alone expand. There was one very big exception to this, the public sector, which has seen an expansion and strengthening of trade union organisation.

The second factor is that the working class in Britain suffered a series of major defeats during the 1980s. Although space does not permit me to go through a detailed history of the events that led up to those battles, a very brief outline does help put the movement’s strengths and weaknesses in context.

The end of the Second World War ushered in an era of economic expansion and increased profitability in Britain. These favourable economic conditions enabled unions and in particular shop stewards to win increases in wages and improvements in working conditions. The shop stewards were the backbone of this movement. The Communist Party may have been relatively small, but it was politically dominant. By this time the CP had become a loyal Stalinist party, the years of the “revolutionary” shop stewards movement were long gone and these CP militants limited the struggle to the winning of concessions, a “DIY” version of reformism. The Peter Sellers film I’m All Right Jack, although mocking these shop stewards, and in particular the CP militant, gives a valuable insight into the shop floor politics of that period.

However, as a series of economic crises hit the world’s economies from the late 1960s onwards, the British ruling class was forced to try and cut wages and conditions in order to increase profitability. Both the Labour government of 1964-1970 and the Tory government under Edward Heath of 1970-74 went on the offensive against militant shopfloor organisation. But determined trade union opposition beat both governments. The zenith of this movement was when the Heath government was brought down by waves of strikes. The historian Royden Harrison noted:

The labour unrest of 1970-74 was far more massive and incomparably more successful than its predecessor of 1910-1914. Millions of workers were involved in campaigns of civil disobedience arising out of the resistance to the government’s Industrial Relations Act… Over 200 occupations of factories, offices, workshops and shipyards occurred between 1972 and 1974 alone and many of them attained all or some of their objectives…

But it was the coal miners, through their victories in the two Februaries of 1972 and 1974 which give a structure, a final roundedness and completeness which the contribution of 1912 had failed to supply to the earlier experience. First they blew the government “off course”; then they landed it on the rocks.

First, they compelled the prime minister to receive them in 10 Downing Street—which he had sworn he would never do—then they forced him to concede more in 24 hours than had been conceded in the last 24 years. Then two years later their 1974 strike led him to introduce the three-day week—a novel system of government by catastrophe—for which he was rewarded with defeat in the General Election. Nothing like this had ever been heard of before!8

When the Labour government came to office in the spring of 1974 it made a tactical retreat before the workers’ movement. It bought off working class discontent and also repealed the Tory anti-union laws. But this came with a price: left wing union leaders like Jack Jones of the Transport and General Workers Union and Hugh Scanlon of the Amalgamated Union of Engineering Workers (two unions which are now amalgamated as Unite) sold the Labour government’s incomes policy, the “social contract”, to their members. The purpose of the “social contract” was to keep wages low. The Labour government also introduced a series of measures to weaken shop stewards’ organisation.

After three years of falling real wages and huge cuts in public expenditure, the dam broke and a series of official strikes labelled by the press as the “Winter of Discontent” rocked the government. But they did not have the same characteristics as the strikes of the early 1970s: they were very bitter and protracted disputes but they did not generalise politically. They were also firmly under the control of national union officials, not the rank and file. By the time of the general election of May 1979 Labour voters were demoralised. This was the political and economic background that enabled Margaret Thatcher and the Tories to come to office.

The primary aim of the Conservative government was to reverse the defeats the ruling class had suffered at the hands of the trade unions in the early 1970s. Unlike Cameron today, Thatcher proceeded cautiously at first, pursuing a strategy—devised by right wing Tory Nicholas Ridley in 1978—of isolating and defeating key groups of workers and slowly introducing anti trade union legislation. The first confrontations were with the steel workers in 1980 and the health workers in 1982. But the key battle took place in 1984-85 when the government and the state took on and beat the miners in a brutal year-long strike. Two more major industrial confrontations followed: the first was with the printers in 1985-86 and then the dockers in 1989. Thatcher won every one of these battles: however, they were all hard fought and during the miners’ strike there were at least two occasions when the government came very close to losing.9

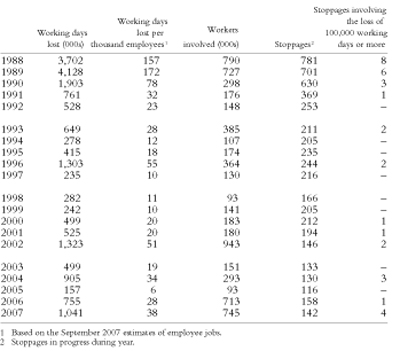

Figure 2: Number of stoppages and working days lost

Source: Economic and Labour Market Review, ONS, June 2008

As well as weakening the trade union movement, the defeat of some of the best-organised sections of the British working class had other serious knock on effects. Firstly, it severely weakened the confidence of workers to fight. From the late 1980s onwards there has been a sharp fall in the number of officially recorded stoppages. There had been an average of seven million officially recorded strike days per year during the 1970s and early 1980s. As Figure 2 shows the decline in the number of strikes over the last 20 years is severe and has only topped the million mark three times in that period.

This has been a tme when there has been a relative stalemate between the employers and the trade unions. There have been some important strikes but none have generalised into a wider fight and neither has any group of workers been smashed in the same way as the miners or printers were in the 1980s. This equilibrium is about to change: this government is desperate to ram through its austerity measures and it is just as apparent that a large section of the population are willing to stand up to it.

We shouldn’t downplay the defeats of the last two decades, but there are a number of encouraging factors which should give confidence to our side. As Figure 1 clearly shows, over the last ten years the decline in union membership has halted and membership may even be increasing. Obviously if the government were to get away with its attacks it would be catastrophic for the working class. Although the trade union movement is half the size it was in 1979, it is nonetheless bigger than it was during the 1910-14 upsurge in militancy and bigger than at any point between 1926 and 1942.

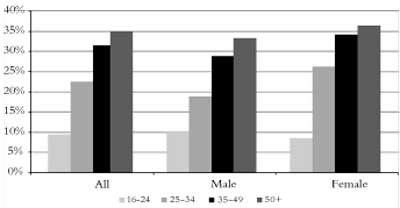

Figure 3: Trade union density by gender and age bands, 2009

Source: Labour Force Survey, ONS

Another problem facing the Cameron government is that Thatcher only half finished the job. She did indeed defeat workers in key sections like mining, docks and steel. However, she left some big battalions relatively intact. Figure 3 shows that union density levels in the public sector, sections of the service sector like transport and power, and core sections of the manufacturing sector remain relatively high. For instance, almost 75 percent of rail workers belong to a trade union and likewise 67 percent of all civil servants.10 But even these statistics do not give a complete picture. There are big variations within sectors. Take, for example, Tesco, Britain’s biggest employer: membership levels for shop workers are relatively low at 26 percent, but among warehouse workers levels reach 78 percent and among drivers 75 percent.11

The problem for the government is that if its austerity measures are going to succeed then it is going to have to defeat some of these core groups or persuade their leaders to hold down struggle. This is not going to be an easy task, as one journalist on the Economist noted: “Public-sector unions enjoy advantages that their private-sector rivals only dream of. As providers of vital monopoly services, they can close down entire cities. And as powerful political machines, they can help to pick the people who sit on the other side of the bargaining table”.12

The government’s strategy of massive cuts in wages, pensions and public services is certainly bold, but it may not be wise. As I stated above, the strategy being deployed by Cameron is in stark contrast to that adopted by Thatcher. Back in the 1980s the Tory government was very careful and only fought one group at a time; it never bit off more than it could chew. This time Cameron is taking on everyone at the same time. If he fails it will be the biggest defeat the ruling class has suffered since 1974, but if he is successful he will have inflicted a huge defeat on the working class.

Statistics that look at the number of strikes, membership levels and density of membership are an important tool, but they present a static and two-dimensional view of what is going on. Previously I wrote in this journal:

Any debate about the nature of class struggle today in Britain has not only to discuss the economic situation but also look at the political and ideological dimensions of the struggle. There are many on the left who argue that an industrial upturn will come about out of a slow rising tide of trade union militancy. Industrial relations academics in Britain often cite the development of trade unions in car plants from the mid-1950s until the mid-1970s as an example of this. Of course this is one model of how an upturn has taken place, and of course this could happen again. But most industrial upturns have not developed this way. For example the upswing of class struggle in Britain in 1889 and 1910, the sit-down strikes in the US in 1934-36, the May events in France in 1968 and the Italian hot summer of 1969 were a product of sudden explosions of anger.13

We have seen sudden and unpredicted explosions of anger in Britain over the last few months. The student protests are an obvious example of this and also the TUC’s demonstration shows there are a large number of people who want to resist the government’s cuts. But it is not all onwards and upwards: as well as anger, there is a great deal of fear inside the working class—people are scared of losing their jobs; they are apprehensive about being able to pay the mortgage or debts. Although this is hard to quantify, it does explain how the Scottish teachers’ union, the EIS, can sell a wage cut to its conference delegates, or the reason why tens of thousands of workers are bullied by management into taking “voluntary redundancy” when there is little prospect of finding another job. The relationship between fear and anger is not a static one. Subjective factors like strong union organisation, reps urging a fight, anti-cuts groups campaigning to save a local community service can tip the balance away from fear and towards anger and action. Given the obvious weaknesses inside the trade union movement and the fact that workers generally lack confidence to fight, the trade union bureaucracy can be a critical factor in any possible fightback.

The trade union bureaucracy

Britain’s trade unions have been in existence for over 120 years now. In all that time we have never had just one “big union” representing all workers. As it says on the tin, they are trade unions and therefore reflect the divisions imposed on them by the capitalist system. Because British capitalism is constantly evolving the unions mirror those changes.

If you were to look at the British trade union movement in 1933 there were just over 300 trade unions affiliated to the TUC and most were numerically smaller than many unions today. So the biggest union in the country in 1933 was the Miners Federation, which had half a million members, and the tenth biggest was the wood workers’ union, which had 97,000 members.14 In 1963 there were 183 TUC affiliated unions. The picture is now very different: by 1995 the TUC had 70 affiliated unions and today it has 58. The two biggest, Unite and Unison, have over 1.5 million members each and the third biggest, the GMB, has over 650,000 members.15 Unison was formed in 1993 and Unite was created in 2007. These so-called “super unions” are a product of merger and not mass recruitment drives.

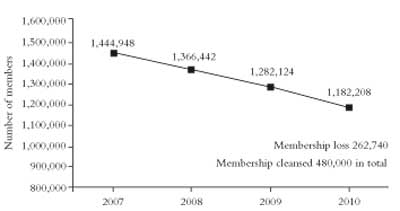

The rise of the “super unions” has not solved the question of retention and growth. Unite was launched in 2007 and it claimed it had over 2 million members. Now the union’s website claims 1.5 million members, a fall of half a million. But the truth is it is even worse than that publicised. Unite has just produced a recruitment strategy document for its full-time officers. It makes depressing reading, and acknowledges that its membership now stands at 1,182,000 members, a fall of nearly 1 million.

Figure 4: Unite membership decline 2007-2010

Source: Unite union

The problem with mergers is that, while they temporarily halt any decline in membership, they do not address the fundamental problems of union decline and do defer any mass recruitment campaigns. If history has taught us anything it has shown that unions expand in struggle and when they can prove they can win real improvements for workers. If a mass strike movement emerges, I believe unions will see workers flock to join their ranks. In the run-up to the Tower Hamlets NUT strike, over 140 people joined the union, an increase of 10 percent in the membership. Again if we look to the past there is a strong case to be made that high levels of nationwide strike activity brought with them rapid and powerful shop stewards movements in Britain, most notably between 1910-1920, 1935-1939 and 1968-1974. The growth of these large unions mirrors the restructuring of British capitalism which has seen the development of large national and global corporations and expansion of the public sector. Bureaucrats have followed a conscious policy of mergers in order to survive

The growth of the large public sector unions demonstrates the changing nature of work in Britain. Up until 40 years ago large professional associations in teaching and local government considered themselves to be superior to unions— they represented workers most of whom felt they were a cut above manual workers. However, as teachers’ and local government workers’ status, pay and conditions were undermined, their associations made the transformation from professional bodies to trade unions and affiliated to the TUC—the National Association of Local Government Officers (now part of Unison) in 1964 and the National Union of Teachers (NUT) in 1970.

Sadly many trade union leaders ape their rivals in other ways. I heard one left wing union leader make a throwaway comment that he was “the CEO” of the union. Figure 5 shows the annual salaries and benefits given to eight of Britain’s union general secretaries and demonstrates how that off the cuff comment could be made. It is a graphic reflection of how far removed their lifestyle is from their members. The truth is all trade union officials who are working full time for the union are subjected to conservative pressures built into the union machine. A very well paid job, free from the daily grind of work, can be enough to subdue the instincts of the best militants.

Figure 5: Annual salary and benefits of trade union secretaries 2009-2010

Source: Certification Office for trade unions and employers association17

| UNION | SALARY | BENEFITS |

| CWU | £87,045 | £1,393 |

| GMB | £84,000 | £28,000 |

| NUT | £111,431 | £22,400 |

| PCS | £85,421 | £27,213 |

| RMT | £84,923 | £28,088 |

| Unison | £94,953 | £35,156 |

| Unite | £97,027 | £89,599 |

| UCU | £97,592 | £15,827 |

The existence of a trade union bureaucracy, a social layer made up of full-time officials with material interests in confining the class struggle to the search for reforms within a capitalist framework, is not a new phenomenon. At the end of the 19th century Sidney and Beatrice Webb wrote a book charting the formation of a trade union bureaucracy. They noted, “During these years we watch a shifting of the leadership in the trade union world from the casual enthusiast and irresponsible agitator to a class of salaried officers expressly chosen out of the rank and file of trade unionists for their superior business capacity”.16

Tony Cliff described the trade union bureaucracy as:

a distinct, basically conservative formation. Like the god Janus it presents two faces: it balances between the employers and the workers. It holds back and controls workers’ struggles, but it has a vital interest not to push the collaboration with the employers to a point where it makes the unions completely impotent. For the official is not an independent arbitrator. If the union fails entirely to articulate members’ grievances this will lead eventually either to effective internal challenges to the leadership, or to membership apathy and organisational disintegration, with members moving to a rival union. If the bureaucracy strays too far into the bourgeois camp it will lose its base. The bureaucracy has an interest in preserving the union organisation which is the source of their income and status.18

Put simply, the trade union bureaucracy balances between the two main classes in capitalist society—the employers and the workers. Precisely because union leaders’ power comes from their ability to defend members’ interests even the most right wing general secretary can be forced to call or support strike action. We have two very interesting examples of this at the moment. The Association of Teachers and Lecturers union is currently balloting its members to strike on 30 June. Traditionally it has been on the right of the trade union movement and last went on strike in 1979.19 Likewise delegates at the Royal College of Nursing conference this year voted to take strike action if their pay was cut, even though the RCN has more in common with a professional association than a trade union.

Two other factors keep the trade union leaders in check. One is the union’s machine—the headquarters, finances and organisation, of which Rosa Luxemburg wrote:

There is first of all the overvaluation of the organisation, which from a means has gradually been changed into an end in itself, a precious thing, to which the interests of the struggles should be subordinated. From this also comes that openly admitted need for peace which shrinks from great risks and presumed dangers to the stability of the trade unions, and further, the overvaluation of the trade union method of struggle itself, its prospects and its successes.20

The same point was put to me rather more succinctly by a full-time official for the predecessor to PCS during an unofficial strike I was involved in at the Passport Office. She told us to “get back to work—we are not going to sacrifice the union for you lot!” That was 1986, and the fear of the bosses using the anti trade union laws has increased tenfold since then. The legislation strikes at the trade union leaders’ Achilles heel. The fear that the courts will impose a heavy fine on the union if it fails to curb unofficial disputes has seen the unions shy away from leading the kind of militant fights that can win. An article published in the Guardian in 2010 noted that over the last five years there were “36 applications for injunction to the high court to block strikes (almost all were successful), all bar seven against planned strikes in transport, the prison service or Post Office”.21

The final conservative pressure on the union leaders is the link between the trade unions and the Labour Party. One feature of advanced capitalist economies is an apparently sharp division between politics and economics. To put it crudely, trade union leaders and the majority of members believe unions deal with economic issues like wages and conditions and the Labour Party deals with winning reforms through parliament. This blunts the struggle and reinforces the idea that negotiation and reform are the only avenues open to workers.

Some claim that Labour’s link to the trade union movement is weakening. Two relatively small unions left the Labour Party in 2004. The RMT was expelled after deciding to allow branches to affiliate to organisations to the left of Labour, and the FBU voted to disaffiliate due to the betrayals of the Labour government during their 2002-03 dispute. But the latest figures published by the electoral commission show that Labour is still very much financially dependent on the trade unions. In quarter four of 2010 the party received £2,545,611 in donations (excluding public funds or “Short money”), £2,231,741.90 or 88 percent of which came from the unions, compared to 36 percent in the final quarter of 2009. Private donations have all but collapsed since Ed Miliband became leader, with just £39,286 raised from individual donations to Constituency Labour Parties. In total the unions were responsible for 62 percent of all Labour funding last year (up from 60 percent in 2009), with one union, Unite, providing nearly a quarter (23 percent) of all donations. Back in 1994, when Tony Blair became Labour leader, trade unions accounted for just a third of the party’s annual income.22

Time and time again we have seen union leaders subordinate their members’ interests to those of the Labour Party. This was patently clear during the Brown/Blair years in government, but the impulse is just as strong now Labour is in opposition. In the run-up to the TUC demonstration leaders of the GMB and USDAW (the shop workers’ union) made it clear that the goal of the demonstration was to help get Labour re-elected and that any strike action that took place before the council elections on 5 May 2011 would damage Labour’s electoral challenge in those elections. The lack of class confidence strengthens the hand of those who say wait for Labour.

As the possibility of large-scale strikes against the government’s cuts are being put on the political agenda, the division between left union leaders and right union leaders can play an important role in events.

Left v right

In 1998 a relatively unknown train driver from Leeds, Mick Rix, won the general secretary election in the train drivers’ union Aslef. Within the space of five years the left won general secretary election after general secretary election. Bob Crow (RMT), Mark Serwotka (PCS), Billy Hayes (CWU), Andy Gilchrist (FBU), Tony Woodley (TGWU) and Jeremy Dear (NUJ) were collectively known as the Awkward Squad.23 The rout of the right was complete when Ken Jackson, the head of Blair’s favourite union Amicus (now part of Unite), lost to a relatively unknown regional officer, Derek Simpson, in 2002. John Edmonds, the former GMB leader, was not exaggerating when he said, “No Blairite can a win a trade union election”.24

The election of these left wing officials and in a few cases activists from the rank and file represented a desire for change. I wrote at the time: “The Awkward Squad’s enthusiasm for political movements like the Stop the War Coalition and the anti-capitalist movement, and its rejection of partnership with the bosses, were and continue to be a breath of fresh air for the trade union movement”.25 But international questions and political movements that take place “outside the trade union orbit” have always been the line of least resistance for the leaders and have been used as a safety valve for the anger of the members.

It was Andy Gilchrist, the leader of the FBU, who famously said: “It’s a well known secret that many of us meet up to discuss. We’ll support each other on specific issues and follow each other’s lead”.26 Well, that was true up to a point; the problem was that this cooperation was confined to a fight within the union structures, to motion mongering at the TUC and, for those affiliated, Labour Party conference. Even in this environment it was a case of the left being pulled by the right.

The clearest example of this took place at the Labour Party conference in Bournmouth in 2003. That was the year Blair ordered the invasion of Iraq. All of the Awkward Squad opposed the war and it should have been the conference at which Blair was brought to task. But he wasn’t—the motion opposing the Iraq war was pulled through lack of support. How could that happen? Derek Simpson and Amicus persuaded the other big unions, the GMB, TGWU and Unison, to unify around a motion on foundation hospitals and pull their support for a motion opposing Iraq. Blair was let off the hook and the most right wing elements of the Awkward Squad set the agenda. When Billy Hayes of the CWU spoke at a fringe meeting later in the week, his excuse was feeble to say the least: “We have to start to set priorities. We have to remember it took the Blairites ten years to take over this party; we have to be patient on what we can achieve”.27

Members of the Awkward Squad have been involved in a number of key disputes over the past 11 years—the firefighters’ dispute of 2002-3,28 the national post dispute of 2007, the public sector pay revolt of 2008 and the BA cabin crew strike of 2010-11.29 They have all been discussed in previous editions of this journal and its sister publications. Without repeating what has been written, in all cases the trade union leaders failed to promote the kind of action needed to win and as a group they shied away from encouraging solidarity action. However, another less pronounced feature of the last decade has been a small number of unofficial disputes—post workers (2003), BA check-in workers (2003), Shell tanker drivers (2008), the second wildcat strike by construction workers at the Lindsey oil refinery (2009) and the Visteon occupation (2009). The tactics deployed were in stark contrast to the official strikes mentioned earlier: they were militant, unofficial and with the exception of Visteon they all involved other workers taking secondary action.

The left in one form or another has won just about every major general secretary election since 1998 (Usdaw is the exception to this rule). It is an indicator that members want leaders who will stand up for their interests. Even when Rix lost the Aslef general secretary election to a right wing populist, Shaun Brady, in 2003, the status quo was soon restored when Brady was removed a year later and replaced by Keith Norman, a mainstream Aslef official and Labour Party member.30 This trend continues. Last year left wing official Len McCluskey, won the Unite general secretary elections and Jerry Hicks, a lay member and someone who would be regarded as part of the hard left, came second with 52,000 votes.

The left’s victories are not just confined to general secretary elections. The hard left has won a large number of national executive seats in unions like the PCS, NUT, RMT, UCU and Unite. In the NUT, PCS and UCU these activists have played a pivotal role in getting the 30 June action off the ground and in the case of the UCU, the national strikes in the lead up to 26 March.

Sharp divisions are once again opening up inside the TUC. The sheer scale of the government assault on trade unions has opened up debates among the leaders of the unions. A small group of unions, ATL, NUT, PCS and the UCU, are pushing for strikes against the cuts in pensions now. Others like Unite and Unison say they will be ready to fight in the autumn. Behind the scenes Paul Kenny of the GMB and Dave Prentis of Unison are complaining that the smaller unions are trying to bounce them into taking action. Socialists should not be neutral in this fight. When a section of the bureaucracy want to fight it makes it easier to win action and, importantly for activists in the unions where their leaders are shying away from action, it makes it easier to point the finger and say, “If that union can fight, why can’t we?”

At the same time it is important not to sow illusions in left wing officials. A J Cook is a name to evoke powerful memories. He is remembered as the man who led the miners during their bitter struggles in the 1920s. He is regarded by many as the most left wing leader Britain has ever had. The Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky wrote a series of brilliant polemics about Britain in the run-up to the General Strike of May 1926. He made absolutely no concessions to any of the left union leaders—even Cook. For example, Trotsky wrote:

Both the right and the left, including of course both Purcell and Cook, fear to the utmost the beginning of the denouement. Even when they in words admit the inevitability of struggle and revolution, they are hoping in their hearts for some miracle that will release them from these perspectives. And in any event they will stall, evade, temporise, shift responsibility and effectively assist Thomas [the right wing leader of the rail workers] over the really major question of the British labour movement. 31

Trotsky was absolutely right. Cook was a prisoner of the trade union bureaucracy. He was a tireless fighter for the miners’ cause, but that alone was not enough. When it became clear that the other union leaders were going to leave the miners to fight alone, Cook was never willing to go over the head of the TUC and call on workers to defy their own leaders’ treacherous behaviour. He was trapped in his own bureaucratic straitjacket .

On a much lower scale, but much more recently, we have seen the same kind of pressures applied to the left union leaders over the last nine months. It was obvious during the summer of 2010 that the TUC was not going to call a demonstration in the autumn. A number of unions began to discuss the idea of holding an autumn demonstration if the TUC failed to organise one. This was absolutely the right response, but the demonstration never materialised. As soon as one leader got cold feet and withdrew support for the demonstration, the others pulled out one by one. In other words, rather than the left pulling the right towards resistance, the opposite occurred. A similar situation occurred earlier this year when some unions tried to set a date for coordinated action around the time of the 26 March TUC demonstration. If hundreds of thousands had gone on strike in the run-up to the demonstration, it would have electrified the trade union movement, but again, with the exception of the UCU, no other union took action. Indecisiveness ruled the day—union officials in the PCS told me that the UCU strike was not “big enough”, while NUT officials said they needed to wait for another teaching union to commit to action before they called a strike ballot. The UCU was different because revolutionary socialists on the NEC pushed the bureaucracy to call the action.32

There is no better guide to how socialists should relate to the trade union bureaucracy than the statement put forward by the Clyde Workers’ Committee in November 1915:

We will support the officials just so long as they rightly represent the workers, but we will act independently immediately they misrepresent them. Being composed of delegates from every shop and untrammelled by obsolete rule or law, we claim to represent the true feelings of the workers. We can act immediately according to the merits of the case and the desire of the rank and file.33

Leon Trotsky put it even more succinctly when he wrote: “With the masses—always; with the vacillating union leaders—sometimes but only as long as they stand at the head of the masses. It is necessary to make use of the vacillating leaders while the masses are pushing them ahead, without for a moment abandoning criticism of those leaders”.34

The last sentence is of particular importance today for socialists. Right now Britain’s union leaders are being forced to fight. When those leaders are pushing a fight we should support them and work with them. This is a doubly important point at this critical stage in the struggle against the government’s austerity measures. There would have been no mass demonstration

of half a million against the cuts unless the TUC had called it; in that situation

it was right for socialists to build the demonstration. Secondly there is no possibility of getting 800,000 workers to strike against the cuts independently right now. The fact that a section of the bureaucracy has called action makes it possible. In this situation socialists should support those leaders who want to fight and criticise those that don’t. But that cannot be all: socialists have to push the action to the next level and be prepared to challenge those leaders who are not prepared to go further. Historically, Britain’s shop stewards/union reps have played a critical role in struggles. Are they still a force to be reckoned with? Have they been incorporated into the union machine? These are going to be crucial questions

in the time ahead.

Union reps: the backbone of the trade union movement

Shop stewards and union reps have played a distinctive role in the British trade union movement. On a local level they hold union organisation together and lead almost every local dispute. They are also the key link between the national union officials and the members. Shop stewards played a pivotal role in a number of important disputes in the last century. In 1919 they led strikes that brought Britain to the brink of revolution and in 1974 the disputes they organised brought the Tory government crashing down. The shop stewards movement has become synonymous with the idea of trade union militancy.

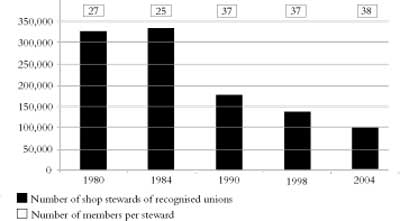

However, there has been a severe weakening of union organisation over the last 35 years . This is reflected in the declining number of shop stewards/union reps, the fact that in many workplaces their bargaining powers have been seriously reduced and that there has be a concerted attempt by both management and union officials to bureaucratise these activists. Any serious assessment of shop stewards and union reps organisation needs to look at both its weaknesses and its strengths.35

The decline of union reps over the last 25 years is worrying, but it is explainable. In 1970 there were around 200,000 stewards in Britain; by 1984 they had reached the 335,000 mark. This dramatic increase was due to the rising levels of militancy and the growth of trade unionism in the white-collar sectors—local government, civil service and health.36 There then followed a sharp fall in union membership and an even bigger fall in the number of shop stewards. As Ralph Darlington points out, recent estimates vary considerably: some believe that the number of stewards in 2004 was around 100,000,37 others as high as 200,000.38 Whatever the truth, it is a serious decline and one rooted in the defeat of key sections of the working class in the 1980s and the decline in industries with strong union representation.

Figure 6: Number of trade union lay representatives 1980-2004

Source: Charlwood and Forth, 2008, p6

The picture is uneven: in the public sector 67 percent of employees work in a workplace with an on-site union rep, whereas in the private sector it is only 17 percent.39 Even within unions there are wide variations. Take for example, the PCS, one of Britain’s better-organised unions—it has an average union rep to member ratio of one rep to every 26 members. However, in some sections like aviation it is as high as one in ten and in others like Siemens it is as low as one in 49.40 Statistics alone don’t really tell you how active the stewards are. Frustratingly, there are no major studies in this area and so a few anecdotes will have to do. During the early part of the year I was involved in building support for the Tower Hamlets Unison strike. The branch has 3,500 members and delivered a very solid strike on 30 March 2011. The branch secretary and assistant branch secretary told me that on average around 25 stewards attend their monthly meeting. They believed that in an ideal world they needed three times that number. Likewise when I was the branch secretary in the London Passport Office in the early to mid-1980s, on average 16 reps attended branch committee meetings. Today it is half that, though the union now incorporates even more workers because the union is open to higher and lower grades.

Passivity is one problem and obviously management offences against trade unions are another. But management are deploying the carrot as well. Alex Callincos wrote: “While capitalist democracy permits the development of working class organisation (not simply trade unions but also the parties linked to the unions, like Labour in Britain), it also seeks to contain those organisations”.41

In the wake of the Donovan Commission’s recommendations (Royal Commission on Trade Unions 1968), employers encouraged a massive expansion in the number of stewards on full-time release. Today it is estimated that 13 percent of all stewards are on full-time facility duties. Ralph Darlington believes that it could involve between 16,000 and 18,000 union reps.42 In the most extreme case I have found, in Usdaw there has been a 28 percent decrease in shop stewards since 1997, but a 50 percent increase in the number of reps on full-time facility time.

This significant increase in full-time facility time for stewards has led to what some industrial studies experts call “steward bureaucratisation”. This is a situation where management are granting convenors/branch secretaries 100 percent facility time to cover large workplaces, often across many sites. Instead of bargaining over wages and conditions (which has in most cases been handed over to national officials) more and more of their time is spent dealing with grievances and disciplinary cases. The effect of this is to remove them further and further away from the shop floor or office. If activists are not careful a gulf can arise between themselves and the members they represent. This is not just confined to stewards on full-time facility time as Waddington and Kerr have noted:

The severe weakening of workplace union organisation today compared with the past has been reflected in the way that many stewards/reps, whether full-time or otherwise, spend less time than previously on collective bargaining issues such as wages and conditions and more time on representing individual members in relation to welfare work, grievances and disciplinary cases. Even though many stewards have undoubtedly displayed an extraordinary level of commitment to holding together workplace union organisation (spending on average 6.3 hours a week on union duties), some of them have also, as a result of often feeling beleaguered and defensive in relation to employers, become fairly cynical towards their members, reflected in an unwillingness to make attempts to mobilise them into taking action. The seeming paralysis of the shop stewards’ network within the car industry—where representation is firmly based in companies such as Vauxhall, Land Rover, Jaguar, Toyota, Nissan and Honda—and an inability to resist wage freezes, lay-offs and redundancies during the current economic recession has underlined the atrophy of organisation. Meanwhile, one of the weaknesses of union organising campaigns in recent years, given the characteristic lack of integration with bargaining agendas, has been the limited extent to which some lay union reps have been involved, with the most bureaucratised reps effectively operating as a barrier to union recruitment and renewal initiatives in some contexts.43

This is not a reason to resist becoming a workplace rep or even a branch officer—precisely the opposite. The union movement needs more activists—abstaining will not strengthen the movement. But activists have to be aware of the dangers; they have to be accountable to the members, fight the pressures that turn them into another “hack”, and encourage strikes. At all times socialists who are reps should put the interests of the rank and file before the needs of the boss or for that matter the union machine. As for the taking of positions with 100 percent facility time, two basic rules should be applied: first, activists should only stand if they have a base and, secondly, why not share the facility time with another activist? There is nothing like working on the shop floor or in the office to keep your feet on the ground.

But it is important not to exaggerate the moves towards “stewards bureaucratisation”. The vast majority of stewards and union reps have held union organisation together through very difficult times and the fact remains that one in ten union reps get no paid time off at all to carry out their duties.44 Also, while it is true that in many industries there has been a centralisation of union power, in other sectors, for example in further education, the civil service and on London Underground, recruitment strategies have been adopted which have encouraged the rebuilding of stewards’ organisation and the decentralisation of negotiating powers.

Yes, today’s stewards/branch reps are too male, pale and stale. But if they are going to revive they need an injection of younger activists. History has taught us that unions and union organisation have grown out of victorious struggles, particularly where struggle has been accompanied by a political strategy to develop such organisation. If you go back to Figure 1 you can see that the revival of union membership coincides with periods of high levels of class struggle: 1910-26, 1936-38 and 1968-84. Conversely, membership and union organisation have tended to fall after major defeats—1926 and 1985 are two obvious cases in point. What are the prospects for such a revival today and what should socialists be arguing?

Where next?

When Bob Dylan’s album The Times they are a–Changin was released in 1964, it captured the spirit of social and political upheaval that characterised much of that decade. If the album had been recorded today it would be just as relevant. Across the Middle East workers, students and the poor have driven out tyrants like Hosni Mubarak in Egypt and Zine El Abidine Ben Ali in Tunisia. The revolt is not confined to North Africa and the Middle East. The spread of austerity across Europe in 2010 has brought with it general strikes in Greece, France, Spain and Portugal, and the explosive emergence of a mass movement in Wisconsin. Not even China is immune: in April 2011 three days of strikes and protests by Shanghai truckers over rising fuel prices shocked the Chinese government, provoking new fears that social discontent over inflation will ignite broader movements

of the working class.

Britain is part of this process: last year’s student revolt is evidence of this. But the resistance is now taking a different form—it is moving away from the street and into the workplace, where workers wield power as an organised force. Just like in the 1980s we face a nasty government, but unlike then it is a weak and increasingly divided government. Unlike Thatcher who picked off one group of workers at a time, Cameron is taking everyone on at the same time—even many on his own side think this is a dangerous strategy.

We have to see the economic crisis as a process, not an event. It will be the dominant factor shaping British and world politics for years to come. In Britain over the coming months the possibility of large groups of workers striking together is going to be discussed in workplace after workplace. It is imperative that activists push as hard as they can to make the demand for coordinated action a reality. If the 30 June strikes take place there will be further pressure on the “big battalions” of Unison, Unite and the GMB to join any future action. From this kind of development you can see how a general strike could develop and therefore why it is important to raise it as a demand.

As I write this article Dave Prentis has told the press, “Unless the government changes direction it is heading for industrial action on a massive scale”.45 Fine words indeed, but we have a responsibility to turn them into action. In concrete terms, that means every trade unionist should be building support for the idea of mass strikes against the cuts in their workplaces. In unions where the leadership is trying to stall any joint action, we need to exert as much pressure on them as possible. But we also have to acknowledge another problem: the gap between the political anger in Britain and the level of class struggle is large. There is a real need right now to bridge the gap between the anti-cuts campaigns and students and the organised working class. This cross-fertilisation will strengthen the entire working class movement.

Individuals matter—they can make a real difference to the outcome of any fight. National coordinated action is one route that may be taken in the struggle to defeat the government’s austerity programmes. But there is also a realistic chance that branch and local disputes may set the pace or run parallel with national action. The nature of the assaults means that there is a local dynamic to the fight. In recent months there have been a number of strikes in local Unison and NUT branches and sections of the civil service. In all of these examples socialists have led the disputes. Every demonstration, every stunt and every community action must be supported and encouraged.

This means that socialists have to raise the big political questions like the call for a general strike and united strike action, but at the same time serious attention to detail has to be applied. Every steward should be recruiting to the union—in particular women, black and young people should be encouraged to become shop stewards/union reps. At the Tower Hamlets strikers’ rally it was encouraging to see the branch officials calling for a general strike, but it was just as impressive to see them afterwards behind a table encouraging strikers to become union reps. We have to ensure over the coming months that we build support for the fight from the bottom up. There is a mood for coordinated action, but that doesn’t mean it will happen. The union leaders’ record is not a good one, the history of the British trade union movement has been one of shoddy compromise and sell out. Today it is no secret that many are nervous about the proposed strikes.

Historically, rank and file organisations have been launched in an attempt to overcome the conservative nature of the trade union bureaucracy. The most famous examples of these movements in Britain developed primarily on the Clyde and in Sheffield among engineers during the First World War, on the buses and in the aircraft building industries during the 1930s and in the mines during the early 1970s.46 This type of organisation also arose in Italy during the “Red Years” of 1918-1920 and

the US in the 1930s.

Rank and file organisations develop during high levels of class struggle and more often than not along workplace lines. But their key feature is that although they often exist within official union structures, because they arise from and are a direct expression of the will of the shop floor, they are militant and soon come into conflict with the trade union bureaucracy. But as the Clyde Workers’ Committee’s first leaflet made clear, they are both prepared to work with the unions, but also to act independently if the union leaders fail them.

I do not believe the creation of a national rank and file movement is possible right now, but, as history teaches us, the situation can change rapidly. The weakness of shop floor organisation, the dominance of the trade union leaders and the lack of confidence of the rank and file to fight make the building of such a movement impossible at the moment.

The terrible record of the trade union leaders does not mean socialists should refuse to have anything to do with them—right now those leaders urging a fight are helping to strengthen the movement. That means we will have to build a working relationship with those officials who want to fight as a means of getting a mass movement off the ground. But we must learn from history: tailing these leaders will not do. We have to ensure that we pull in the direction of strengthening the rank and file and not

subordinating the struggle to the official machine. When debating with British Communists in the run-up to the 1926 General Strike, Trotsky cited Lenin: “Lenin allowed the possibility of a temporary bloc even with opportunistic leaders under the condition that there would be a sharp and audacious turn and a break based on actions of the masses when these leaders began to pull back, oppose or betray”.47

The last task is in some ways the most important. Socialists have always been at the heart of any revival of working class militancy. Eleanor Marx and Ben Tillett played a central role in the great unrest of 1889, which led to the formation of mass general unions in Britain. Revolutionary socialists like Willie Gallagher and J T Murphy were central to the first shop stewards movement on the Clyde and in Sheffield, and the Communist Party helped to organise the revival of the trade unions in the 1930s. Today socialists have to throw themselves into the developing struggles. The wave of strikes which engulfed Britain in 1889 were predicted by no one and led by unorganised workers. The following year a massive May Day demonstration was held in London, Frederick Engels, Marx’s lifelong collaborator, was there and wrote: “The English working class, rousing itself from 40 years of winter sleep, rejoined the movement of its class”.48

Maybe, just maybe, this sleeping giant is awakening again.

Notes

1: Hughes, 2001, p140.

2: Socialist Worker, 23 April 2011.

3: Guardian, 8 July 2010.

4: Interviewed by the BBC, 8 August 2010.

5: Smith, 2010.

6: See the online report at www.socialistworker.co.uk/art.php?id=24397

7: See www.statistics.gov.uk/articles/nojournal/Analysis.pdf

8: Harrison, 1978, pp1-2.

9: Robertson, 2010.

10: PCS, 2011.

11: USDAW, 2010.

12: Economist, 6 January 2011.

13: Smith, 2005, p113.

14: Clegg, 1987, p570.

15: www.tuc.org.uk/tuc/unions_main.cfm-as seen in Figure 4, Unite’s membership actually stands at just under 1.2 million, but for consistency I have used the TUC’s own figures in all cases.

16: Sydney and Beatrice Webb, 1919, p577-578

17: Certification Office for trade unions and employers association, Annual Report of the Certification Officer, 2009-2010, p66.

18: Cliff and Gluckstein, 1986, p27.

19: Mary Bousted is the general secretary of the ATL. Over 30 percent of her members work in private schools and by any criterion they are a conservative section. But even among these workers the anger is palpable. To get a flavour of the mood of the ATL conference and a taste of how a trade union bureaucracy can move to the left you can read her speech at the ATL website-www.atl.org.uk

20: Luxemburg,1970, pp214-215

21: Guardian, 2 April 2010.

22: Electoral Reform Commission, 2011.

23: The order of the election victories follows, Mick Rix 1998, Andy Gilchrist 2000, Mark Serwotka 2000, Billy Hayes 2001, Jeremy Dear 2001, Bob Crow 2002, Derek Simpson 2002 and Tony Woodley 2003. Paul Mackney, who was also one of those involved in the informal grouping, became Natfhe (now part of UCU) general secretary in 1996.

24: Telegraph, 7 September 2002

25: Smith, 2003, p2.

26: Vallely, 2002.

27: Guardian, 3 October 2003.

28: Smith, 2003, pp13-15.

29: Kimber, 2009, pp46-55.

30: If you are so inclined you can read a blow by blow account of the Rix/Brady battle at www.labournet.net/ukunion/0408/aslef21.html

31: Trotsky, 1973, p167.

32: The discussions about an alternative demonstration or coordinated strikes in March have only been covered in Socialist Worker (23 April 2011) and Socialist Review (April 2011). I have spoken to officials in both the PCS and NUT who have confirmed the events I have outlined.

33: Hinton, 1973, p296.

34: Trotsky, 1973, p172.

35: For this section I have borrowed very heavily from Ralph Darlington’s excellent article-Darlington, 2010, pp126-134.

36: Charlwood and Forth, 2008, pp3-4.

37: Darlington, 2010, p127.

38: BERR, 2009, p2.

39: DTI, 2007

40: PCS, 2011

41: Callinicos, 1995, p15.

42: Darlington, 2010, p128.

43: Waddington and Kerr, 2009, pp27-54.

44: TUC, 2007.

45: Telegraph, 2 May 2011.

46: Fishman, 1995, provides a very useful analysis of the development of rank and file groups on London buses and in the aviation industry,

47: Trotsky, 1973, page 256.

48: www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1890/05/23.htm

h2. References

Achur, James, 2009, Trade Union Membership 2009 (Office for National Statistics).

BERR, 2009, Reps in Action: How Workplaces Can Gain From Modern Union Representation, (Department for Business Enterprise and Regulatory Reform).

Callinicos, Alex, 1995, Socialists in the Trade Unions (Bookmarks).

Charlwood, Andy, and John Forth, 2008, “Workplace Employee Representations 1980-2004”, NIESR discussion paper, www.niesr.ac.uk/pdf/240708_152852.pdf

Clegg H A, 1979, The Changing System of Industrial Relations in Great Britain (Blackwell).

Clegg, H A, 1987, A History of British Trade Unions since 1889, volume 2: 1911–1933 (Clarendon).

Cliff, Tony, and Donny Gluckstein, 1986, Marxism and Trade Union Struggle, The General Strike of 1926 (Bookmarks).

Darlington, Ralph, 2010, “The State of Workplace Union Reps’ Organization in Britain Today”, Capital and Class, volume 34, number 1, http://cnc.sagepub.com/content/34/1/126.full.pdf+html

Department of Trade and Industry, 2007, “Workplace Representatives: A Review of Their Facilities and Facility Time”, www.berr.gov.uk/files/file36336.pdf

Electoral Reform Commission, 2011, “Political Parties’ Latest Donations and Borrowing Figures Published”, www.government-news.co.uk/electoral-commission/201102/political-parties-latest-donations-and-borrowing-figures-published.asp

Fishman, Nina, 1995, The British Communist Party and the Trade Unions 1933–45 (Scolar).

Harrison, Royden, 1978, The Independent Collier (Harvester).

Hinton, James, 1973, The First Shop Stewards Movement, (George Allen and Unwin).

Kimber, Charlie, 2009, “In the Balance: the Class Struggle in Britain”, International Socialism 122, www.isj.org.uk/?id=529

Hughes, Langston, 2001, The Collected Works of Langston Hughes, volume 1 (University of Missouri Press).

Luxembourg, Rosa, 1970, Rosa Luxemburg Speaks (Pathfinder).

PCS, 2011, “National Organising Strategy 2011” (PCS).

Robertson, Jack, 2010, “25 Years After the Great Miners Strike”, International Socialism 126, www.isj.org.uk/?id=640

Smith, Martin, 2003, The Awkward Squad, Let’s Go to Work: New Labour and the Rank and File (SWP).

Smith, Martin, 2005, “Trade Unions: Politics and the Struggle”, International Socialism 105, www.isj.org.uk/?id=55

Smith, Martin, 2010, “Everything to Play for”, Socialist Review (October),

www.socialistreview.org.uk/article.php?articlenumber=11406

Trotsky, Leon, 1973, Leon Trotsky on Britain (Pathfinder).

TUC, 2007, “Workplace Representatives: A Review of their Facility Time—TUC Response to DTI Consultation Document” (TUC).

Unite, 2011, “A Union-Wide Strategy to stop decline and grow Unite” (Unite the Union).

USDAW, 2010, “Going for Growth” (USDAW).

Vallely, Paul, 2002, “Profile: Andy Gilchrist”, Independent (23 November),

www.independent.co.uk/news/people/profiles/profile-andy-gilchrist-609260.html

Waddington, J, and A Kerr, 2009, “Transforming a Trade Union? An Assessment of the Introduction of an Organising Initiative”, British Journal of Industrial Relations, 47/1:27.

Webb, Sydney and Beatrice, 1919, The History of Trade Unionism 1616-1920 (Edinburgh).

WERS, 2004, “Workplace Employment Relations Survey”, www.wers2004.info