The need to “seize back control of fishing rights in British waters” was pitched as a symbol of all that was wrong with the European Union by the Leave campaign in the 2016 referendum.1 The right-wing Brexit campaign, including Nigel Farage and the Fishing for Leave organisation, used Britain’s maritime history and long fishing traditions to invoke a myth of plucky and beleaguered but independent individuals battling the EU and foreign fishers hell bent on stealing “our” fish.

Fishing for Leave described itself as “fighting to reclaim British fisheries and rebuild the industry to benefit all communities and fishers”.2 The campaign group repeatedly asserted that Britain’s fishing fleet had been robbed of most of the available fish in its territorial waters.3 Despite this, according to government figures, the British fleet had the “second-largest total catch by landed weight and the second-largest fleet size by gross tonnage when compared to EU countries” in 2019.4

It is true that many fishers in Britain, Europe and the rest of the world have been robbed of their ability to make a living.5 It is also true that fishing has declined in importance to the British economy. In 2019, the sector was worth only £437 million, 0.02 percent of GDP; in comparison, financial services were worth £126 billion.6 However, the Brexit deal agreed by the British government in January 2021 made very little difference to the amount of fish available to British registered or owned boats.7 The little the deal said about fishing also did not change how much fish Britain’s boats could take. Nor did it change the country’s responsibilities to comply with international laws concering maintenance of fish stocks—Britain is still required by transnational agreements to minimise damage to marine biodiversity and practice sustainable aquaculture.

Commercial fishing in British waters is integrated into a world system designed to maximise profit extraction from the marine resources available. The production of food for humans and livestock is not entirely incidental to the process, but it is secondary to the accumulation of profit. Access to the majority of marine species legally available for British-registered fishing vessels is owned and controlled by a few rich or very rich people. The capitalists who own the means of fish production constantly compete with their British rivals, their counterparts from other European countries and sometimes even capitalists from further reaches of the global fishing industry, such as fishmeal producers in Peru.8

The project of European integration aimed at creating a capitalist block that could rival the United States, the Soviet Union and other states. This involved tying fishing in Britain and other European countries to a developmental course that demanded job cuts, the introduction of new technology and a series of technical measures that are discussed below. All this was targeted at increasing the profitability of the fishing industry.

The effects of this are clear to see in the British fishing industry. As in other countries, this sector comprises both wild-caught and farmed fish, which are sold as fresh, chilled, frozen and canned fish products. The industry has been profoundly reshaped over the past 40 years by capitalists who have sought to control and develop integrated supply chains in food production and marketing to customers.

Fish retailing is now dominated globally by supermarkets. In Britain, this was worth £4 billion between June 2019 to June 2020, with just three chains—Tesco, Sainsbury’s and Aldi—taking 47.8 percent of total sales.9 As the largest buyers, supermarkets have been able to control supply of many products and even buy up suppliers. Their desire to ensure reliable stocks and prices, and to standardise products, has driven the growth of aquaculture (the cultivation of fish, shellfish, crustacea and other species) over the last four decades. Despite the elevated risk of disease outbreaks, farmed marine and freshwater species have become a more reliable source of supply, price and profit than wild-caught fish. This is particularly the case with salmon, tilapia and shrimp.

Today, the British fishing industry faces a perfect storm of capitalist crisis, compounded by the effects of the pandemic and Brexit, overfishing and climate change. To understand how the industry got to this state, this article looks at what has happened to fishing, fishers and fishing communities in Britain since the Second World War, tracing the development of capitalist property relations, food production and retail. I focus on the development of the EU and its Common Fisheries Policy, because it has shaped the state of the industry today. I also consider why fishing still carries such political weight and what the real solutions are to ensuring that fishing has a sustainable future, providing both food and jobs that are safe and well paid.

Bailing out capital: post-war modernisation

Britain’s fishing fleets needed extensive rebuilding and modernisation in 1945. During the Second World War, the government set maximum fish prices. Fish and chips were never rationed, but supply was restricted through rationing of potatoes and fat and by smaller catches. In 1945, catches of cod, whiting, haddock, hake and pollock were 29 percent lower than in 1938 in Scotland and 59 percent lower in England. This was partly because thousands of fishers had joined the Royal Navy Patrol Service at the beginning of the war, and many fishing boats became minesweepers, rescue and supply ships, and armed escorts for convoys. By the end of the war, more than 400 trawlers, drifters and whalers had been destroyed, including 96 trawlers from Hull alone. Horrifically, nearly half of the 1,243 British fishers killed came from Grimsby, Hull’s sister port across the Humber estuary.10 Catches were also lower during the war because the remaining fishing boats had been restricted to the west coast of Scotland, the Irish Sea, some other places off Ireland and the waters around Iceland, where Britain’s long-distance cod fleet had fished for centuries.

Despite Britain’s fishing fleets being in poor shape by the end of the war, boat owners with capital were reluctant to invest. Indeed, few of them had ever been happy to seriously invest in boats that could, after all, sink and take the money down with the crew. Instead, they expected the state to invest in their fleets, just as it had since 1750, when legislation provided for government money to fit out specialist herring boats called busses.11 There are also more recent examples of state investment such as the government’s creation and funding of the Herring Industry Board from 1935. The board, formed from the Scottish Herring Producers’ Association and the English and Welsh Herring Catchers’ Associations, lent money for building new boats, reconditioning old ones and buying fishing gear. Boats were divided into “inshore” vessels of up to 24 metres, “near water” vessels of up to 33.5 metres and larger “middle-water” vessels, which included distant water steam trawlers and whalers. Fishing methods and technology varied depending on the species being caught, with many methods, such as seine netting and trawling, having been used for centuries before mechanisation.12 “Drifters” caught herring in long drift nets; ring-nets and purse-seiners surrounded shoaling fish such as mackerel and tuna; “liners” used multiple baited hooks on lines; and shellfish, crabs and lobster were caught in pots.

Public money paid for refits, new gear and motor boats. Many of the Royal Navy’s 13.7-27.4 metres vessels were now turned over to fishing. From the late 1940s, fishing vessels were refitted with more efficient diesel engines, but this was a slow and uneven process. Indeed, 967 fishing boats in Scotland were still registered as sailing vessels in 1950.13 However, a decade later, John Hare, minister for agriculture, fisheries and food, told parliament that there were only 150 “coal-burner” fishing boats and that “the number of diesel trawlers has risen from 179 in 1956 to more than 330 today”.14

Handing large amounts of public money to owners concentrated capital in fewer hands. Jobs were cut and profits buoyed by increasing the size of boats, trawls and lines. This process also accelerated the industry’s reliance on fossil fuels, which had begun since sailing drifters were first converted to steam trawlers in the 1870s. New technologies such as nylon nets—much lighter and stronger than cotton ones—and the power block, a mechanised winch invented by Croatian fisher Mario Puratić, revolutionised the hauling of fish-filled nets in the 1950s. Sonar and echo sounding technology, developed during the war to detect submarines, now became available, making fish easier to find. Improved refrigeration and freezing methods enabled factory trawlers to stay at sea for weeks at a time.

The White Fish Authority, established in 1951, handed out grants and loans to owners of “inshore, near and middle-water sections of the British fishing fleet”. It also provided cash operating subsidies for whitefish and herring boat owners, although this was supposed to be a temporary measure while the fleet was modernised. Nevertheless, Hare made it clear in 1960 that the subsidies would continue: “We do not intend to leave the industry in the lurch should the circumstances of the day be such that continuance of government aid in one form or another is necessary”.15

Some fish stocks were under pressure in the 1930s from earlier technology such as steam and motor trawlers. The 1933 Sea Fishing Industry Act set up the Sea Fisheries Commission to govern British North Atlantic cod fishing, restrict fishing for cod in the summer and prevent immature fish being caught, but this had little impact.16 The wartime exclusion of most fishing from the North Sea gave species a brief chance to recover, but diesel-powered boats with purse-seine nets could surround most of a herring shoal in its coastal spawning grounds, and thus catches fell again by 1947. This was also the year the Herring Industry Board opened its first factory, processing herring into fishmeal for animal feed and oil for ice cream and margarine. This was part of a wider push by the British, European and US food industries to drive up profits by processing foods with cheaper ingredients, while meat consumption and production were increased with the help of advertising.17

The Herring Industry Board was processing up to 50 percent of Britain’s herring catch by 1950, when the herring population in the North Sea collapsed due to overfishing.18 Local fishery collapse was not peculiar to Britain—there were many such incidents around the world in the 20th century, driven by new technologies that boosted commercial fishing’s ability to overfish.19

Dangerous work

The owners who got government support to modernise and operate boats still argued that profits were too tight to improve safety on their trawlers. Between 1976 and 1995, 616 people died in British fishing, mainly from sinkings and trawling nets getting snagged. Many others were made disabled by accidents. Dangerous conditions were exacerbated by exhausted crew members being encouraged to keep working until the fish holds were full.20 In winter, a tonne of ice could form on decks and rigging in minutes in bad weather, and crews had to chip it off by hand without even safety lines with which to attach themselves to the boat. Less than 20 tonnes of ice could capsize a 657 tonne ship such as the Hull trawler Kingston Peridot, which sank off Iceland in January 1968, killing all 20 men aboard. Fishers had to buy their own bedding and work clothing, and their work brought risks of serious injury and death. Employers ignored available safety measures in order to maximise profit, and crews who refused to sail could be blacklisted by owners and captains.

The Kingston Peridot was the second of three Hull trawlers that sank in early 1968. When news reached families of the disaster, the fishing community, centred on Hessle Road, erupted in rage and grief. Hundreds came to the first campaign meeting, which was organised by Lillian Bilocca, whose husband, son and father were trawlermen. “Big Lil”, as she was affectionately known, had started a petition with demands for better equipment, more radio operators and more experienced crews. She managed to get the journalists and television crews besieging the town to sign it. The campaign grew into marches and direct action as hundreds of women demanded change, especially when another trawler sank. From the three Hull trawlers lost that winter—St Romanus, Kingston Peridot and Ross Cleveland—there was only one survivor, Harry Edom. Edom was the mate on the Ross Cleveland and had been on deck in his oilskins “duck suit” when his ship went down, thus managing to get into a lifeboat and then ashore.21

Chrissie Smallbone, whose entire family worked in the fishing industry, and dozens of other women threw themselves into the campaign. Smallbone was on her way to meet Bilocca with some of the other women when a television reporter with a microphone stopped her. She expressed her fury about the owners’ practice of sending out so-called Christmas cracker crews over the Christmas and New Year holidays, when experienced men were at home with their families. These crews were made up to full complement with 15 to 17 year olds as “deckie learners” and older men with little or no fishing experience. Smallbone raged:

There’s been that many men lost at sea in the last five years that we aren’t going to put up with it anymore. There’s too many 15 year olds going to sea what don’t know anything about it, and there should be a training course for those 15 year olds before they set foot on a trawler. We want more experience aboard, especially at Christmas.

Another woman said:

There should be a wireless operator on every ship. For a skipper can’t be on the bridge and in the wireless room at the same time, can he?

A third woman added:

And the owners…they don’t care. All they are interested in is the fish. The men, they don’t mean a thing to them. They could not care less what happened to them as long as they are bringing the fish back.22

In the face of vilification, the campaign managed to unite workers whose shore-based jobs usually set them at odds with trawlermen. Even students from the University of Hull marched in solidarity. The women’s protests and media appearances made international news, leading to a complete overhaul of safety standards on British trawlers.

Exclusive Economic Zones and the “cod wars”

The idea of “exclusive economic zones” (EEZs) that would further expand property relations at sea emerged in the early 20th century. They aim to allow national states to control access to waters and species adjacent to their coastlines. As EEZs developed they allowed states to claim special rights over marine resources, so that foreign fishers theoretically had to pay to access EEZ fisheries from which they had previously taken as much of the “free gift” of fish as their skill, equipment and luck allowed. States owning EEZs could now gain rents from other states that wanted access, effectively appropriating part of the surplus value created by the labour of foreign fishers working in their waters.23

EEZs were codified in the Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea between 1973 and 1982, but the motivation to form EEZs had already got a powerful boost when the US claimed exclusive rights to mineral resources miles off its coasts after the Second World War.24 However, it was more difficult for smaller states to establish EEZs and control their natural resources because their waters had often been fished for centuries by foreign fishers.

For British long-distance trawlermen, the most important attempt to establish an EEZ began when Iceland became an independent republic in 1944. The Icelandic government’s attempts to control access to its nearest fisheries, their only major industry, meant keeping British and other foreign trawlers out. However, after centuries of fishing these waters, British fishers failed to see why they should leave. So, when Iceland’s government unilaterally extended its fishery limits from 3 to 4 nautical miles (7 kilometres), the dispute known as the “cod wars” took off between the two countries.25

The British government and trawling industry owners banned Icelandic boats from its ports, assuming Iceland would back down because Britain was its largest fish export market at the time. Yet, Iceland’s government increased its territorial waters to 12 nautical miles in 1958, using its 100 coastguards and six gunboats to fire blank and live shells in order to ward off British trawlers. In turn, the British fishers were protected by 37 Royal Navy ships. When the final cod war dispute was settled in December 1976, Iceland had extended its territorial waters to 200 nautical miles, effectively destroying Hull’s long-distance trawler industry.

At the same time, every fishing port and village in Britain was being affected by the growing complexity and reach of the European Economic Community, the predecessor of the EU, which culminated in the creation of the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP) from 1970. If the CFP really intended, as it claimed, “to ensure sustainable fisheries and guarantee incomes and stable jobs for fishers”, it has been an unmitigated disaster.26 Hundreds of thousands of fishing and fishing-related processing jobs have disappeared from communities in villages and towns in every coastal state in Europe. This has hit fishers from the north of Iceland and the Scandinavian states to northern Germany, Poland, Spain and around the Mediterranean to the Black Sea. Just as in Hull, these fishing communities have experienced how “capitalism can create and then dismiss a way of life”.27 Moreover, the CFP also helped destroy fishing communities along the coast of West Africa, where EU-flagged boats purchased fishing rights from individual African states, robbing fishing communities of their fish and their livelihoods.

The chief result of the CFP has been the concentration of capital in fewer, larger and more profitable boats. Owners got very rich while target species were overfished for decades. The CFP is an expression of capitalism’s drive to accumulate for profit, as well as a distorted response to the ecological destruction wrought as individual states’ fishing fleets have used technological improvements to compete with one another for market share. This has been the CFP’s core contradiction—it is impossible to protect commercial fishing profits and fisheries’ ecosystems, yet it has claimed to do both.

Inevitably, the CFP has provoked protest. Inshore fishers used their boats to blockade major ports all over Britain for three days in 1975, angry at the policies of the EEC, falling fish stocks, imported frozen fish, high fuel prices and too little support from the government. The blockade was called off after talks with the ministry, and the fishers claimed they had won concessions.28 The Scottish Trawler Federation (STF) and Scottish Fishermen’s Federation said they agreed with all the issues raised by the fishers, but they failed to join the blockades, probably because their focus was on larger trawlers and owners with substantial capital.

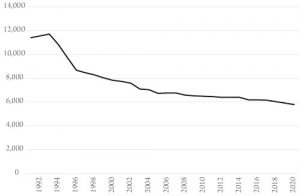

Protests, lobbying and clashes between the fleets of different EEC and EU member states continued over decades. In response, the EU introduced technical measures to tackle the CFP’s problems without challenging the logic of profit. These included paying owners to decommission older, less profitable boats in the 1990s in order to make fishing more efficient and profitable. This cut European fishing fleets by 40 percent, causing a corresponding loss of jobs. The number of working boats based in Britain has dropped by 26 percent since 1996 (see figure 1). Fishers based in Britain numbered around 12,000 in 2019, down from 20,000 in the 1990s and just a fraction of those directly employed on fishing boats in the 1950s.29 Some 60 percent of the 4,301 active fishing vessels in Britain in 2020 were under 10 metres in length and generally fished within six miles of the shore.

Figure 1: Total British fishing fleet size 1991-2020 by number of boats

Source: Marine Management Organisation.

Other measures included setting minimum net mesh sizes and minimum landing sizes, individual transferable quotas, legislation to restrict the numbers of days some fishers could be at sea and most recently the so-called landing obligation or “discard ban”. But each of these measures has in its own way failed to protect species and fishers’ livelihoods.

Individual transferable quotas

Individual transferable quotas (ITQs) were pitched as a means of preventing overfishing by setting limits on each boat’s catch alongside a total allowable catch (TAC) for each target species in a particular area. ITQs were pioneered in New Zealand fisheries in the 1980s, further developed in Iceland in the 1990s and then brought into the EU’s Common Fisheries Policy. They effectively enclosed areas of sea by privatising access to fish in the same way that landowners had enclosed land for private hunting grounds in previous centuries. TACs were based on “maximum sustainable yields” determined for each species by fisheries scientists and were intended to maximise efficiency by not “wasting” fish by taking “too little”. ITQs were allocated by the boat’s catch history, favouring larger boats and owners of multiple boats. Fishers with smaller boats were often disadvantaged by being unable to prove their fishing record in enough detail. Many were unable to compete with larger boats with bigger quotas and instead sold their quotas, becoming employees on someone else’s boat or getting out of fishing altogether. Others worked alone to try to make their work pay enough to cover their costs, but these fishers were typically incapable of affording to maintain and replace safety equipment. Their work became more dangerous than it needed to be, and accidents and deaths more likely. Some could not afford insurance; if their boats were wrecked, they would still have to make loan repayments for a boat that no longer existed.30

Quotas commodified access to fish, and those with more capital could buy up quotas whether they actually fished or not. These so-called slipper-skippers stayed ashore, selling or renting quotas out, as and when it was profitable. This also created “quota hopping”, whereby an EU citizen could buy and register a fishing vessel in, for example, Britain in order to gain access to quotas allocated to British fishers. All this was legal. However, despite Fishing for Leave’s claim that quota hopping was the industry’s main issue, it was mostly a problem for fishers with substantial capital, who disliked competition and how speculation in ITQs drove prices up. Unearthed, Greenpeace UK’s investigative journalism body, showed in 2018 that Britain’s five largest quota holders controlled over a third of the total British fishing quota. Four of these were members of families on the Sunday Times Rich List, and a fifth was a Dutch multinational whose British subsidiary, North Atlantic Fishing Company, controlled about a quarter of England’s fishing quota.31 Christina S, the trawler used in the infamous “Brexit Flotilla” stunt with Nigel Farage on the River Thames in 2016, was owned by a partnership of some of these “codfathers”.32 By leaving the EU, the richest people involved in Fishing for Leave hoped to get hold of quotas held by companies based in the Netherlands, Iceland and Spain, which held around half of England’s fish quotas in 2020.

Wasted fish

ITQs also ensured that thousands of tonnes of edible fish were thrown back to the seagulls and virtually guaranteed that any organised effort to flout the rules would be highly profitable. For instance, Shetland Catch Limited, a fish processing company based in Lerwick, colluded with dozens of captains to not report landing undersized mackerel and herring up to 700 times between 2003 to 2005. The fish was sold for around £47.5 million. This was illegal and various participants were convicted, but the compensation orders and fines imposed together came to less than £5 million.33 In its defence, Shetland Catch argued that, if it had not accepted the illegal fish, it would have been landed on the Scottish mainland, taking local processing jobs with it. More generally, fishers protested that they were obliged to throw away edible fish; the European Commission itself estimated this waste at some 1.7 million tonnes a year in EU waters.34

Eventually the EU introduced the landing obligation for pelagic species such as herring and mackerel in 2015, and it was implemented for all species subject to quotas by 2019. With less fish being wasted, the EU increased total allowable catches by up to 50 percent for affected species. However, a 2020 report by Our Fish, which campaigns against overfishing, argued there was no demonstrable cut in fish discarded and little enforcement of the ban. The landing obligation may prove to be just another sticking plaster that allows the CFP’s wounds to fester.35

“Working the ground”

Fishing communities have managed ecosystems for thousands of years, protecting them from overfishing and damage. Examples of strict customary regulations in indigenous communities include Māori people in New Zealand, who prohibited fishing and even travelling by boat through coastal fisheries in spawning seasons. Polynesian people in Hawaii limited catches from reefs to protect them for future generations.36 For thousands of years, people have created and managed fishing opportunities through techniques such as the fish weir capture systems of aboriginal Australia and southwestern Spain, which protected immature fish. These systems allowed ecosystems and biodiversity to thrive, but also enabled humans to capture substantial quantities of mature fish.37

Unfortunately, capitalism’s prioritisation of profit over the health and reproduction of species and their ecosystems has created a generalised and deep crisis in the relationship between humans and nature—the so-called metabolic rift.38 Yet, fishers remain skilled experts; they do not just pull species out of the water. Instead, they carry out “working the ground”, knowing their actions can bolster biodiversity or destroy it.39

Depending on where they are, fishers without quotas can work to capture various species regulated by licence rather than quotas, such as squid, scallops and some types of crab. These species were made profitable at some point because fishers were able to link to markets and sell them for more than they cost to catch. For instance, the first recorded commercial catches of velvet crab in Scotland happened in 1985 when a Spanish buyer contacted fishers on the west coast of Scotland to ask whether the crabs were available. Relatively few people in Britain ate velvet crab in the 1980s compared with the “edible” or brown crab with its crimped pasty-like shell, but the velvet crab were extremely popular in Spain. A fisher went looking for them, worked out how they could be caught using modifications to his existing equipment and developed ways to transport them alive to markets in Spain. By 2009, 2,762 tonnes of velvet crab were landed with a total value of £6.1 million.40 These fishers creatively managed an ecosystem, creating a fishing ground with their labour. They understood when it could be worked and when it had to be rested to remain productive and were highly protective of it. Such examples show that fishers can be part of the solution to environmental degradation and biodiversity loss. They stand in contrast to the solutions pitched by capitalists, who do not challenge the primacy of profit, such as aquaculture.

Aquaculture

Aquaculture, the farming of marine and freshwater species, has been heavily promoted as a sustainable solution to overfishing and the biodiversity loss linked to climate change. The British government and the EU has supported it over the past 40 years, and in Britain alone was worth over £962 million by 2018. Typical products can include muscles, oysters and rainbow trout, but 82 percent of produce in 2018 was Atlantic salmon farmed in floating cages along the west coast of Scotland. Seafish, a government body set up to support fishing, describes it as an “efficient, industrialised” sector. In Britain total aquaculture production was 189,921 tonnes by live weight in 2018, with a first sale value of over £962 million before any of it was processed.41 The industry provides tonnes of relatively cheap salmon to eat all year round. It is, however, unsustainable. When domestic fish escape and breed with wild salmon, their fast growing genes undermine the survival chances of wild salmon.42 By concentrating sometimes hundreds of thousands of fish and their waste in small areas, farmed salmon cages have also become centres of disease and pesticide-resistant lice.

Proponents of salmon farming and other industrial aquaculture argue that the problems it causes are minor when compared with its potential to feed the world. This has become a frequent argument used by those pushing “solutions” to capitalist problems that fail to challenge the principle of profit above all else. Yet, aquaculture around the world has the potential to foster catastrophic disease that move back and forward between farmed and wild fish, which could ultimately interrupt and even end the profitability of the industry, no matter how well it suits supermarket supply chains. Climate change too is exacerbating the mounting pressures on wild species and their ecosystems. In particular, ocean acidification, caused by water absorbing more carbon dioxide as more is released into the atmosphere, is doing great damage. Acidification undermines the capacity of crustaceans, shellfish and other species to grow their shells, leaving them vulnerable to predators and disease and less likely to successfully reproduce. Environmental degradation is also compounded by pollution, changing land use and warming water.43

Brexit

Fishers in Britain were promised a great deal from Brexit. Fishing for Leave said it would mean “the restoration of our water to national control”.44 The reality of leaving the EU has been much more complicated however. Shellfish and crustacean fishers were affected badly by Brexit and the subsequent deals because Britain became a “third party” that must “purify” shellfish for export to the EU. Fishers argued this was an expensive, time consuming and unnecessary public health measure since the same species caught in the same waters by EU vessels were considered fit to eat. Nevertheless, this is simply how exclusion from competition works, as every fishing state in Africa that could potentially export its products to the EU knows. Brexit has also generated substantial bureaucracy around the planned annual negotiations for sharing out fish with a new system for settling disputes. It is likely that rich fishers and companies with large amounts of capital will benefit, being able to afford to buy bigger quotas as they become available between 2021 and 2026.

Since 2021, boats from Britain and EU member countries need a licence to fish in each other’s waters. Technically, Britain could exclude EU member states boats from its waters after 2026, but the current struggles over access to fishing licences shows how incendiary such an imposition would be. The licences are based on boats being able to show they have worked in a particular area from 1 February 2017 to 31 January 2020. The problem for fishers with smaller boats is that they usually cannot afford the “automatic identification systems” used by larger boats that collect this data. Britain’s Marine Management Organisation did launch an app with which boats under ten metres can log their catches from the end of 2019, and over 77 percent of the fleet signed up within six months of it going live. However, the app does not help with proof for 2017 and 2018. Fishers from both sides of the Channel could be kept out of waters they have worked for decades. The recent new battles between France and the Channel Islands over access to licences were fuelled by years of frustration over different fishing methods and claims about who is considered to be taking too much of some species. These have involved boats from France, the Netherlands, Kent, the Channel Islands, Brixham and other ports in Devon and Cornwall. Fishers who promote sustainable fishing have been angry about larger boats and more destructive fishing methods.

Table 1: Most important species landed by the British fleet in 2020, by weight

|

Species |

Weight in tonnes |

|

Mackerel |

205,000 |

|

Herring |

75,000 |

|

Blue whiting |

52,000 |

|

Haddock |

75,000 |

|

Cod |

25,000 |

Source: Motova, 2021.

Last November, fishers in France blocked British boats from access to the French ports where they land fish and blocked trucks at the Eurotunnel freight tunnel with burning pallets. French minister of the sea Annick Girardin talked about taking “retaliatory measures” if licences were not issued by the government of Jersey, implying that France could cut off electricity currently supplied to the island via undersea cables.45 Nonetheless, fishers also joined Greenpeace’s “No Fish, No Future” campaign last year against industrial fishing companies with “super trawlers”, which operate with mile-long nets in the English Channel alongside ones with the latest “fly-shooter” nets that can take as much fish as a hundred smaller boats.46

Table 2: Most important species landed by the British fleet in 2020, by value