Sub-Saharan Africa is huge. Its area is larger than that of China, the United States and India combined or five times that of the 28 countries of the European Union. Its population, at over 930 million, is also getting on for twice as much as that of the European Union. The 48 countries of the region are also extremely varied, both in size and economic history, with many small countries and giants such as Nigeria. This article aims to provide an overview of the economic history of sub-Saharan Africa since independence (around 1960 for most countries).

At the beginning of the 20th century sub-Saharan Africa was “an overwhelmingly land-abundant region characterised by shortages of labour and capital, by perhaps surprisingly extensive indigenous market activities and by varying but often low levels of political centralisation”.1 This shortage of labour was overwhelmingly due to the slave trade. In the 200 years to 1850 the population of Africa did not grow significantly. In contrast, the population of Europe grew over four-fold in this period. But sub-Saharan Africa was also ravaged by the effects of colonialism. From the end of the 19th century sub-Saharan Africa suffered around 60 years of colonial plunder and as a result, “on a continent of household-based agrarian economies with very limited long-distance trade, colonialism imposed cash-crop production for export, and mineral extraction, with manufacturing supposed to come later”.2

The relative underdevelopment of the African economy can therefore be traced to a number of factors. As a result of colonialism, many of its national economies became virtual monoculture (mineral or commodity) exporters. They are also dependent on imports for equipment, capital goods, the bulk of their consumer goods, know-how and technology. By the 1980s only five countries (Benin, Sierra Leone, Morocco, Senegal and Zimbabwe) had diversified export bases.3

Primary production still dominates sub-Saharan Africa’s exports.4 The economies of many African countries are heavily dependent on the export of one or two commodities. As a result they are more susceptible to the vagaries of world price changes and other external shocks than more diversified economies.5 The result of such adverse shocks from the late 1970s and the subsequent introduction of neoliberalism, was the further growth of incredible inequality within Africa. While over two thirds of Africans still exist on less than $2 a day,6 there are also Africans among the richest people in the world. Aliko Dangote of Nigeria, with a net worth of 14.9 billion US dollars, is richer than anyone in Britain. Nicky Oppenheimer and Johann Rupert of South Africa are richer than all but three people in Britain.7

There is, of course, also gross inequality between Africa and the industrial world. This inequality has exploded over the last two centuries. As an example of the comparability of their economic development, in the late 19th century some African states were still able routinely to defeat European armies: for example, a popular uprising led to the death of Charles Gordon, Britain’s governor general of the Sudan in 1885, and the British retreat from Sudan. Similarly, in neighbouring Ethiopia, an Italian army of 20,000 was massively defeated at the Battle of Adowa in 1896. In West Africa the armed forces of the Asante Empire defeated the British forces and killed their commander, the governor of the Gold Coast (now Ghana) in 1824. The Asante again attacked the coastal area of the Gold Coast between 1869 and 1872 and were only finally defeated in 1874.8

Whereas in 1820 the average European worker earned about three times the wages of the average African worker, now the average European earns around 20 times as much.9 In addition, there is great inequality between countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. Economically, the continent is dominated by Nigeria and South Africa; combined they account for around three quarters of the region’s GDP. Their companies are very active across sub-Saharan Africa and their governments act as sub-imperial powers, even aiding Western imperial powers. During 2013, for example, Nigerian troops helped to replace the French forces in northern Mali and 13 South African paratroopers were killed in the Central African Republic during the overthrow of its former president.

Despite the diversity of national economic experiences, the economic history of sub-Saharan Africa can be broadly divided into four sub-periods:10

-

1960-1980, when the growth of many African economies equalled that in many other areas of the world—annual GDP growth of 4.8 percent.11

-

1980-2000, when economic growth collapsed in many African countries as a result of the external shocks of oil price increases, declining terms of trade and increased real rates of interest—annual GDP growth of 2.1 percent.12

-

2000-2007, when many African economies recorded reasonable economic growth largely from the significant increase in the prices received for primary products—annual GDP growth of 3.9 percent.13

-

2008-present when economic uncertainty returned with some decline in demand for raw materials with the slow down in the European and American markets and reduced growth in the Chinese economy.

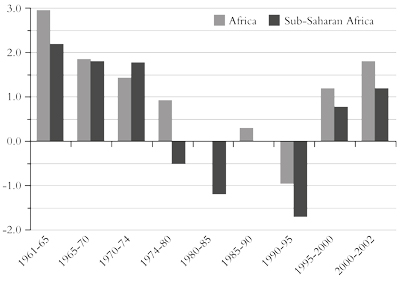

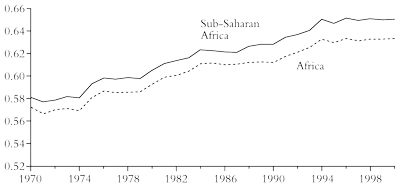

The broad trends of economic growth in sub-Saharan Africa (and Africa as a whole) over the last half a century are shown in figure 1. The recent economic prosperity, termed “Africa rising”, has largely been grabbed by the economic elite. It will take more sustained struggle by the growing working class to see a significant reduction in poverty over the coming decades. But the huge struggles, especially in South Africa and Nigeria, in recent years have indicated that this is a distinct possibility.

The medium-term effects of the ongoing global Great Recession on Africa are not yet clear and the economy still faces a significant number of key risks.14 Initially there was a marked slow-down in economic growth, but there has now been some economic recovery, although prices of primary products have moderated recently.

Figure 1: Average per capita GDP growth rates (percentage)

Source: Artadi and Sala-i-Martin, 2003

In 1970 around 48 percent of the population of sub-Saharan Africa existed on less than $1 a day. By 1995 this had increased to 60 percent.15 Despite the economic growth over the recent past, the World Bank16 estimates that almost one in two people in sub-Saharan Africa still have to live on less than $1.25 a day and their numbers are still increasing (because of the inequality of economic growth). In addition, average per capita income is currently probably as much as 10 percent less than its peak in 1974.17

Great hopes at independence

As John Saul and Colin Leys said:

At independence—between 1955 and 1965—the structural weaknesses of Africa’s economic position were generally recognised and it was assumed on all sides that active state intervention would be necessary to overcome them. Although Africa would still be expected to earn its way by playing its traditional role of primary-product exporter, the “developmental state” was to accumulate surpluses from the agricultural sector and apply them to the infrastructural and other requirements of import-substitution-driven industrialisation.18

Ten African countries enjoyed a consistent GDP growth rate of about 6 percent a year between 1967 and 1980, some of them ranking at times with the best performing East Asian economies. For example, over this period the Kenyan economy grew faster than that of Malaysia and the economy of Côte d’Ivoire grew faster than that of Indonesia.19 Giovanni Arrighi points out that “up to 1975, the African performance was not much worse than that of the world average and better than that of South Asia and even of the wealthiest among First World regions (North America)”.20

The origins of the debt crisis

The Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) was able significantly to increase the price of crude oil with its oil embargo in 1973. This provided vast windfall gains for oil-producing states such as Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Abu Dhabi. However, as David Harvey describes, the US was only prepared to accept the oil price increases if the profits were channelled through US investment banks.21 So, perhaps partly as a result of the threat of US military intervention, the banks suddenly found themselves with massive funds for which they needed to find profitable outlets. As the returns from investments in the US and Europe were depressed, “governments seemed the safest bet because, as Walter Wriston, head of Citibank, famously put it, ‘governments can’t move or disappear’”.22

At the time it was widely accepted that governments should borrow to invest in public infrastructure and also to meet other demands that could not be met due to the relative reduction in commodity prices (see below). This was widely abetted by the World Bank and others; they “coached and encouraged” many African governments who were “ambivalent borrowers”.23

The experience of the US and Britain in the years immediately following the Second World War had shown that extensive government borrowing could facilitate economic growth (in particular circumstances). In the US the federal debt alone (excluding state or local government debt) reached over 120 percent of GDP in 194624 and in the UK government debt peaked at nearly 250 percent of GDP25 at around the same time. In the circumstances of the long economic boom of the 1950s and 1960s, these levels of public debt proved to be sustainable and indeed may have facilitated the sustained economic growth of these years.

However, most African governments were not to be so lucky. Many borrowed heavily (but not to the post-war levels of the US or Britain), but then their economies suffered a series of external shocks that meant that governments were not able to repay these loans. Heads of African governments voiced their position in the 1980 Lagos Plan of Action. This placed most of the blame for the then dire economic performance of sub-Saharan Africa on factors beyond the control of its governments—namely, the seemingly ever-declining real commodity prices and declining overall terms of trade, world recession, rising international interest rates and debt burden, and extended periods of drought26 which the economically ravaged governments were less able to manage.27

Declining terms of trade

The rapid increase in world interest rates in the early 1980s (see below), on top of the oil price rises, tipped a world economy already suffering declining profit rates into recession. As a result most developing countries faced a reduced demand for their exports while having to pay much higher interest rates on their debts (and higher oil prices in the case of oil importing countries). The reduced demand for primary products and the relative decline in their prices continued from the 1960s until the early years of this millennium, as the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) reported: “There has been a long-term downward trend in real nonfuel commodity prices since 1960…the commodity prices recession of the 1980s was more severe, and considerably more prolonged, than that of the Great Depression of the 1930s”.28

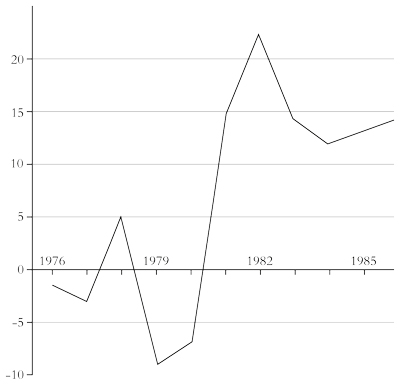

Figure 2: Composite commodity price index 1948-82 (1977-9 = 100)

Source: World Bank, 1983

Christian Aid also reported: “The prices Third World countries receive for many of their traditional exports, from coffee and cocoa to rice, sugar and cotton, continue to decline. The relative value of their exports has declined even more—for example, in 1975 a new tractor cost the equivalent of 8 metric tons of African coffee, but by 1990 the same tractor cost 40 metric tons”.29 The reduction in commodity prices is shown in figure 2.

The terms of trade for low income African countries declined by over 15 percent during 1973-6 and by nearly 14 percent further during 1979-82.30 However, official projections at the time by the World Bank and others continually indicated that prices for raw material exports from sub-Saharan Africa would soon improve, reinforcing the hopes of African governments that the decline in the price of their main exports would only be temporary. As a result: “Many governments dealt with this problem by short-term borrowing, creating the long-term debt burden”.31

This decline in the terms of trade did not just arise naturally, but was due, at least partly, to explicit policies, this time adopted by the World Bank. As Michael Barratt Brown commented, the prices of nearly all primary products had a “steady downward trend from the late 1970s. The cause must in part be the [World] Bank’s encouragement of all primary commodity producers to pay off their debts by increasing their exports”.32 In addition, the World Bank itself also noted:

Between 1980 and 1986 the real prices of primary commodities fell sharply… Several factors were at work. Slower growth in industrial countries had depressed demand. Over the longer term, shifts in technology continued to reduce the demand for industrial raw materials. Meanwhile supply had expanded. Growing subsidies and trade protection—as provided, for example, by the EC’s Common Agricultural Policy—caused overproduction in the industrial countries. Output had also expanded in developing countries in response to the high prices of the early 1970s. Past investment in infrastructure, new techniques, and improved domestic policies also contributed.33

Some commentators, for example the dependency theorists such as Samir Amin, have argued that the declining terms of trade, theorised as unequal exchange, arise from the differences in power relations between the “centre” and “peripheral” countries.34 However, this does not explain the significant improvement in the terms of trade for many African countries over the last 15 years or so (see below) or the improved terms of trade for Africa in 1940-50.35 In addition, the dependency approach can fall into the trap of seeing exploitation as being between countries, rather than workers in each country being exploited by their bosses. If the former were really the case then African nationalist responses would be more appropriate than the strikes and other forms of class struggle we have seen within African countries in recent years.

According to the World Bank, changes in the terms of trade cost non-oil producing African states (excluding South Africa) a total of 119 percent of their annual GDP between 1970 and 1997.36 External debt grew by 106 percent of GDP over the same period. So all the external debt of African countries at the end of the 20th century could be explained by falling prices for their exports and increasing prices of imports—both changes over which their governments had little or no control. The cost of debt also increased due to sudden increases in world interest rates.

Interest rate rises

In October 1979 the United States government significantly increased interest rates, which reached nearly 20 percent by July 1981,37 in a battle to throttle back its persistent inflation.38 This “Volcker shock” led directly to a massive increase in world interest rates. The real (inflation adjusted) interest rates paid by governments of the Global South increased from -4 percent in 1975 to over 10 percent a decade later, as is shown in figure 3.39

Figure 3: Inflation adjusted (real) interest rates on external borrowings of developing countries 1976 to 1985 (in percentage points)

Source: World Bank, 1988

As a result of these increases in interest rates and repeated devaluations, the amount that Africa had to pay to service its debt increased from around 2 billion US dollars in 1975 to 8 billion dollars by 1982.40 “Once the Mexican default of 1982 dramatically revealed how unviable the previous pattern had now become, the ‘flood’ of capital that Third World countries (and Latin American and African countries in particular) had experienced in the 1970s turned into the sudden ‘drought’ of the 1980s”.41

So the economy of sub-Saharan Africa faced a triple whammy in the early 1980s of declining terms of trade, increased interest rates on existing debts and lack of access to further loans.

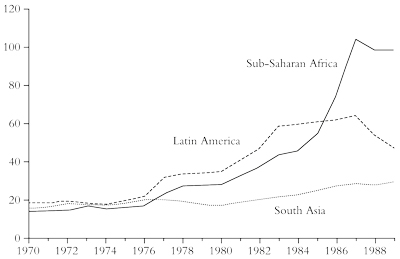

The rising problem of government debt

UNCTAD describes the result: “From just over $11 billion in 1970, Africa had accumulated over $120 billion of external debt in the midst of the external shocks of the early 1980s. Total external debt then worsened significantly during the period of structural adjustment in the 1980s and early 1990s, reaching a peak of about $340 billion in 1995”.42 Figure 4 shows this graphically.

Figure 4: Total external debt (as percentage of GDP)

Source: Elbadawi, Ghura and Uwujaren, 1992

The impact of worsening economic conditions, increased rates of interest and the imposition of penalties for failure to repay loans on time meant that African debt soared despite considerable repayments having been made. UNCTAD43 calculated that between 1970 and 2002 sub-Saharan Africa received $294 billion in loans, paid back $268 billion in debt service, but was still left with debts of some $210 billion.44 In the case of the Nigerian government, for instance, the amount originally borrowed was less than 15 billion dollars. However, after paying 15 billion dollars to service the debt, the country still owed $26 billion in 2005.45

As a result, many governments were not able to pay the interest or repayments, 14 countries in sub-Saharan Africa had their debts rescheduled in 1984-546 and 11 African countries defaulted on their debts in the 1980s.47

Structural adjustment made the situation worse

By the mid-1980s most of the government debt in sub-Saharan Africa was owed to the World Bank and IMF.48 This gave these institutions the leverage they needed to implement their newly adopted policies of deregulation and privatisation through what were called structural adjustment programmes (SAPs).49 These almost invariably included the following elements of what is now called neoliberalism:

reduced government spending and greater fiscal discipline to control inflation.

removing import controls and restrictions on foreign investment.

privatisation of state enterprises.

devaluation of the currency.

allowing the market to set foreign exchange rates, interest rates and the price of commodities.

making labour more flexible by reducing legal protection, food subsidies and minimum wages.

The SAPs were replicated across most countries in sub-Saharan Africa over the next decade with grim results.50 Economic growth declined from over 3 percent in 1985-90 to less than half of this figure for 1991-5.51 Even the World Bank itself found the results disappointing. A 1992 study found that: “World Bank adjustment lending has not significantly affected economic growth and has contributed to a statistically significant drop in investment ratio”.52

In a study covering 220 reform programmes sponsored by the World Bank, more than a third were judged to have failed by the World Bank’s own Operations and Evaluation Department.53 As the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa concluded:

SAPs exacerbated the crisis of the state in Africa… The limited state capacity at their birth was weakened as the public sector and public bureaucracy became major targets for state budget cuts, often inspired by SAPs. The paradox of SAPs is that, while the state was expected to lead the process of economic reforms, stabilisation and transformation, its capacity was dismembered, and it became unable to pursue the reform measures effectively. SAPs frequently held back economic growth and social progress, negating the construction of developmental states.54

The immediate result was “IMF riots” in many countries (caused by the food price increases from the removal of government subsidies demanded by the IMF). Riots brought down the governments in Liberia, Sudan and Zambia and threatened several others.55 As the economic downturn continued, popular protest movements and strikes brought down more than 30 African regimes between 1990 and 1994.56 These movements were galvanised by resistance to structural adjustment or the neoliberal counter-revolution, but also by the democratic revolutions across Eastern Europe.

Resultant economic developments

The impact of structural adjustment on the general economy of most African countries was devastating. Deregulation and the opening up of economies to the global market did not result in a significant growth in manufacturing; indeed the result was often deindustrialisation. For example, the textile industry in Nigeria was decimated. The textile production index (1972 = 100) for Nigeria declined from 427.1 in 1982 to 171.1 in 1984.57 When Nigeria joined the WTO the textile industry suffered from cheap imports of new cloth from India and China and second hand clothes from Europe.58 At its peak there were 250 factories directly employing around half a million workers, but less than 25 now remain.59

UNCTAD explained that:

The main cause of deindustrialisation in a number of developing countries in the 1980s and 1990s lies in their choice of macroeconomic and financial policies in the aftermath of the debt crises of the early 1980s. In the context of structural adjustment programmes implemented with the support of the international financial institutions, they undertook financial liberalisation in parallel with trade liberalisation, accompanied by high domestic interest rates to curb high inflation rates or to attract foreign capital. Frequently, this led to currency overvaluation, a loss of competitiveness of domestic producers and a fall in industrial production and fixed investment even when domestic producers tried to respond to the pressure on prices by wage compression or lay-offs.60

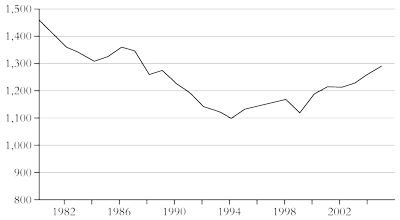

In 1989 even the World Bank was forced to admit that “overall Africans are as poor today as they were 30 years ago”.61 Between 1980 and 1987 the real income per capita in sub-Saharan Africa fell by about a quarter. Eight African countries (Chad, Ghana, Liberia, Madagascar, Niger, Uganda, Zaire and Zambia) experienced severe drops in real income per capita of more than 20 percent between the early 1970s and late 1980s.62

The reversal in economic development during sub-Saharan Africa’s “lost decade” is shown dramatically in figure 5 (we will discuss later the partial recovery since the mid-1990s, largely based on improving terms of trade).

Figure 5: GDP per capita in poor sub-Saharan African countries, 1980-2005 (in constant PPP dollars, weighted by average GDP for 2001-5)

Source: IMF Independent Evaluation Office, 2007, p8, Based on World Bank, world development indicators

The International Labour Organisation reported in 1990 what this meant in terms of African wages: “a sharp fall in real wages…an average 30 percent decline between 1980 and 1986… In several countries the average rate has dropped 10 percent every year since 1980”.63

Similarly, the declaration from the UN Khartoum conference of 1988 concluded: “Regrettably, over the past decade the human condition of most Africans has deteriorated calamitously. Real incomes of almost all households and families declined sharply. Malnutrition has risen massively, food production has fallen relative to population, the quality and quantity of health and education services have deteriorated”.64

Although the details varied from region to region and from country to country, the overall picture was the same. Accounts from individual countries may suggest that it was problems with internal policies, the behaviour of their governments and civil servants. But when the timing of the economic reversal is so similar in so many countries, this suggests that the economic problems were mainly due to common external events rather than the particular domestic approach of individual governments.

It is true, as Saul and Leys argue, that “the ‘developmental state’ became primarily a site for opportunist elements to pursue spoils and lock themselves into power”.65 But this corruption was (and is) a symptom of Africa’s economic problems and the huge resultant inequality, not its main cause, as the World Bank and others would like to claim.

The lost decade for Africa continues

The lost decade of economic crisis extended into the 1990s as the declining terms of trade continued and was made worse by capital flight, the brain drain and the devastating effect of HIV/AIDs.66

Capital flight

Léonce Ndikumana and James Boyce show that over the period 1970-2008 sub-Saharan Africa was a net exporter of capital to the rest of the world.67 Total capital flight over this period amounted to $735 billion (in 2008 dollars)68 compared to an external debt of only $177 billion; “according to one UNCTAD study, Africa received US$540 billion in loans between 1970 and 2002 and paid back US$550 billion. Yet in 2002 the continent still owed US$295 billion because of imposed arrears, penalties and interests”.69 For every dollar Africa borrowed externally, more than 50 cents immediately left the country in the very same year in the form of capital flight.70 The people benefiting from capital flight are the local elites who, in cooperation with the multinational companies, engage in mispricing of imports and exports to get round any local regulations on the export of capital that had not been removed as a part of the neoliberal reforms.71 Deregulation and the ending of controls over capital exports as part of neoliberalism make capital flight possible and far more difficult for local governments to control.

Brain drain

Capital flight also takes the form of the brain drain. Not only is Africa providing financial capital to develop the rest of the world, but it is also providing it with intellectual capital. It is estimated, for example, that over a quarter of the graduates (especially in such fields as engineering, science and medicine) have emigrated from West Africa and nearly a fifth from East Africa.72 As a result, taxes in Africa are being spent on educating a minority of the population to university level whose expertise is then used to benefit the economies and companies in the industrial countries.

In contrast much of the development aid sent to Africa is immediately repatriated to industrial countries via payments to consultants. The loss of key professionals by emigration from Africa has led to the use of foreign consultants whose daily rate is often equivalent to the monthly salary of local officials. In 1995 it was estimated that there were 100,000 expatriate experts working in Africa at a cost of $4 billion.73 In 2005 the World Bank admitted that $20 billion of the $50 billion global aid budget was spent on consultants.74

AIDS

The acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) pandemic was first recognised in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in the mid-1980s. From there it spread to Uganda, Tanzania and Kenya, and also spread southwards, via Zambia to Botswana and South Africa. By 2005 some 25 million Africans were living with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV/AIDS) and over 13 million had died: “the inadequacy of Africa’s medical systems, especially when eroded by structural adjustment programmes, not only slowed the initial recognition of the disease but contributed greatly to the sufferings of AIDS patients and delayed the adoption of antiretroviral drugs”.75

This had a devastating effect on the economy, especially in Southern Africa, with, for example, several countries having more teachers dying each year from the disease than were graduating from teacher training colleges.

Although the AIDS pandemic is now coming under control in most African countries “nearly 9 percent of sub-Saharan 15 to 49 year olds are living with HIV/AIDS”.76 Around two thirds of people living with HIV/AIDS globally are living in Africa and half of these are in ten countries: Angola, Botswana, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, Swaziland, Zambia and Zimbabwe. In 2009 some 1.8 million more people became infected with HIV/AIDS in Africa and around 1.3 million people in Africa died of AIDS related deaths (three quarters of the world total).77 In Mozambique, for example, around 1.4 million people were living with AIDS in 2009 and only slightly more than 10 percent of these were receiving antiretroviral drugs.78

A new approach or more of the same?

The debt problem continued and its impact on government finances continued to be catastrophic. In 1999 it was estimated that “the Highly-Indebted Poor Countries (HIPCs) spent one third of their tax revenues in servicing their debts. In some countries such as Angola (84 percent), Côte D’Ivoire (62 percent), Guyana (48 percent) and Sierra Leone (50 percent), this ratio was much higher”.79 By 2000 sub-Saharan African governments were still spending over twice as much on debt service as on basic healthcare and almost as much on debt as they spent on education.80

In 1999 the IMF and World Bank agreed a “new” approach. Low income countries wanting financial aid or debt relief under the HIPC initiative were required to develop “poverty reduction strategies”.81 But these included many of the standard neoliberal prescriptions and still have to be signed off by the boards of both the IMF and World Bank. Limited debt relief was eventually made available to some governments that accepted this further conditionality.82 But this was designed more to ensure that the remaining debts were repaid than to assist economic development.83

The HIPC initiative has not provided a significant reduction in the debt burden actually suffered by many African countries. Annual debt service relief in 2003-5 for the 20 HIPCs involved was not much more than one 20th of the foreign aid these countries had received in 2000.84

Economic growth returns for the 21st century

The economies of sub-Saharan Africa finally managed to achieve reasonable economic growth in the early years of the 21st century achieving real per capita growth of over 2.5 percent each year from 2002 to 2008.85 Indeed, “of the world’s 15 fastest growing economies in 2010, ten were African”.86 But this was mainly driven by the price boom for primary products: “Since independence, African growth has been driven by primary production and export and only limited economic transformation, against a backdrop of high unemployment and worsening poverty”.87

Over 50 percent of the economic growth of sub-Saharan Africa in the 21st century was due to increased commodity revenue thanks to higher demand especially from emerging economies such as India and China.88 The countries to which sub-Saharan Africa exports have diversified. The proportion of exports, going to the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) have increased from less than a tenth in 2002 to more than a third in 2012. This is now comparable to the level of exports to the European Union and the United States combined. China is now the largest destination for African exports taking nearly a quarter of the total (having increased from only 5 percent in 2000).89 China has also become the largest single trading partner for the region, a key investor and provider of aid.90

Other significant factors in sub-Saharan Africa’s growth included huge inflows of foreign direct investment, mainly for the extractive industries,91 development aid and increased remittances from nationals working abroad. Remittances from Africans working outside Africa exceeded foreign direct investment from 2007 and overtook development aid from 2010.92

However, prices for export goods remain volatile and so place future economic growth at a significant risk.93 Therefore growth in Africa has been followed by a return to uncertainty in recent years (figure 6). Growth declined after 2007 (although it was still 3.9 percent in 2013 and was projected to be 4.8 percent in 2014)94 and became more erratic as a result of the impact of the Great Recession and the decreasing rates of growth in China. Commodity prices remain at historically high levels although they weakened in 2013. The world prices of agricultural goods, metals and minerals fell by nearly 10 percent in the first six months of 2013 compared to the year before and there remains at least the potential for a longer-term decline.95

Figure 6: Africa’s annual percentage GDP growth, 2000-12

Source: OECD/AfDB, 2014

This risk is made worse as most sub-Saharan African countries are dependent on the exports of only a few commodities. As pointed out earlier, three quarters of these countries rely on three commodities or less for 50 percent or more of their export earnings.96

Over the decade to 2012 economic growth in China averaged more than 10 percent. This growth rate moderated to less than 8 percent in 2012 and 2013,97 with the slower rate of growth translating into lower industrial metal prices. For example, the price of copper, a key export for several African countries including Zambia, decreased by more than a third from its 2011 peak.98

Overall, Chinese economic interests in sub-Saharan Africa are still significantly lower than the US and the former colonial powers of Britain and France. These three countries together hold nearly two thirds of the total FDI stock in Africa and the value of each country’s stock is around double that of Chinese companies.99

Africa’s growing economic links with China also carry associated risks, as China is still relatively independent of these links. China’s investment in and trade with Africa represents only 3 percent and 5 percent of its global investment and trade, respectively.100 In addition, Chinese investments are concentrated in a few countries. South Africa accounts for nearly a third of this investment and, together with Nigeria, Zambia and Algeria, takes over half of all Chinese investments in Africa.101

The experience of the 1980s led many African governments to take a cautious view of debt and maintain reasonably tight fiscal and monetary policies. Partly as a result, inflation has generally been modest, at around 5 to 10 percent for sub-Saharan Africa since 2005. But it peaked at around 20 percent in East Africa in 2011-12. 102

The other major risk is an increase in global interest rates that could be triggered by the further reining back of the US programme of quantitative easing. This would result in governments paying more for their public debt. The number of governments suffering debt distress or at high risk of distress fell from 17 to seven between 2006 and 2012, but this could change with a significant increase in global interest rates.103 A more serious problem could be the associated reduction in foreign direct investment which has been partly fuelled by low global interest rates: “the search for yields among investors has supported strong capital flows to developing countries in recent years, including sub-Saharan African countries”.104 The impact of this risk would be increased if it was also to be combined with weaker prices for raw commodities.

Financial flows to Africa reached a record high in both 2011 and 2012 driven by foreign investment and remittances from Africans working abroad.105 However, these financial flows are concentrated in a few countries, with the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Nigeria and South Africa amounting to perhaps half the total.106 In addition, the overall net position is that sub-Saharan Africa continued to be a net contributor of capital to the rest of the world during at least the first decade of the 21st century (due mainly to continued capital flight).107

The Great Recession led to a reduction in donor aid to sub-Saharan Africa, although it was again more than Foreign Direct Investment from 2009. Donor aid is not expected to increase over the medium term and half of donor aid is received by only six countries making up a third of the population; these are headed by South Africa and Nigeria.108

Economic growth is not equitable

Unlike in the period 1960 to 1980, the economic growth of the early years of the 21st century did not benefit the majority of the population: “Africa’s high growth rates have not translated into high levels of employment and reductions in poverty… They are also quite volatile, especially in sub-Saharan Africa”.109

The higher levels of inequality resulting from the neoliberal policies of privatisation, deregulation and a more regressive taxation system—associated with an increase in corruption—mean that the rich local elite benefited most from the increased prices for raw materials. One symptom of this is the huge property boom in Accra, Ghana, Dar es Salaam in Tanzania and other cities of the continent.110 Another is the growth in the travel industry in Africa. Demand for passenger aircraft in Africa is expected to grow from the existing 600 to over 1,500 in the next 20 years. Some 40,000 new rooms are also planned by international hotel developers in the coming years.111

Figure 7 shows a clear increase in the Gini coefficient (measure of income inequality) across sub-Saharan Africa from the mid-1970s to at least the mid-1990s. Other studies have shown that inequality has continued to increase in a large number of countries across sub-Saharan Africa into the 21st century.112 South Africa, for example, is now considered to be the most unequal country in the world with the Gini coefficient increasing until at least 2009 and the proportion of the GDP going to wages falling from over 50 percent in 1995 to less than 45 percent by 2010.113 Of the top ten most unequal countries in the world, six are in sub-Saharan Africa.

Figure 7: Income inequality in Africa (Gini coefficient)

Source: Artadi and Sala-i-Martin, 2003

In this situation there are increased demands for redistribution as well as economic growth to address poverty and inequality and for more deliberate government intervention in the economy and a return to the developmental state of the early post-independence period.114

The role of inequality in slowing poverty reduction in Africa is now becoming widely accepted.115 The World Bank is even suggesting that basic income grants provided to all citizens, at least in resource rich countries, would have a significant impact on poverty reduction.116 This is in recognition of the fact that across sub-Saharan Africa the number of people having to live on less than $1.25 a day increased by around 10 percent in the first decade of the 21st century.117

The issue of food production is critical for the region with over 60 percent of the continent’s labour force still being employed on family farms.118 Africans have been encouraged to grow crops for export, especially over the last 50 years. In addition, relaxation of import controls has meant that an increased proportion of food is obtained from imports with prices often undercutting local food production. As a result, local farmers have reduced the cultivation of food crops and so the food prices, heavily dependent on imports, are now more susceptible to the vagaries of the world market, the weather and climate change.119

The urban poor in particular are suffering from the high food price inflation that is expected to continue over the medium term as a consequence of global warming (reducing yields across sub-Saharan Africa), cultivation of cash crops rather than food crops and other factors. This is being made worse with high food prices and the development of agrofuels leading to a new scramble for land in Africa by multinational agribusiness.120

Unemployment also remains high, with official estimates of around 25 percent in South Africa and Nigeria.121 In each case the real rate of unemployment may be significantly higher and young people in particular are finding it very difficult to find work, a particularly significant factor in a continent where half the population is under 25 years old.122 In addition, where people do find jobs, many of these are in the informal sector. It is estimated that only 16 percent of the labour force across sub-Saharan Africa works in the formal sector with 62 percent working on family farms and the remainder in the informal sector.123 Even in South Africa, where the informal sector is much smaller, outsourcing, labour brokers and contractors have reduced the number of permanent jobs. In mining, for example, it is estimated that one in three workers is employed by a contractor or sub-contractor rather than directly by the mine owners.124

In South Africa the proportion of people living on less than one US dollar per day fell from 11 percent to 5 percent of the population between 1994 and 2010. However, nearly a third of the population still have to survive on $2 a day or less. In 2012 the Nigerian minister of information claimed that Nigeria had the third fastest growing economy in the world.125 However, the proportion of people living in poverty increased from 54 percent in 2004 to 72 percent in 2011126 and about two thirds of the population in Nigeria lives on less than US$1.25 per day.127 Meanwhile almost half of the income is consumed by only 10 percent of the population.128

Increasing urbanisation, unionisation and protest

United Nations data shows that about 15 percent of Africa’s population were urban dwellers in 1950. This is expected to rise to 50 percent by 2030. This urbanisation has been associated with huge increases in the size of the African working class. The African Regional Organisation of the International Trade Union Confederation, ITUC-Africa, now has 94 affiliated organisations in 48 African countries and a membership of 16 million.129 The working class in Africa is now playing an increasingly important role across the continent with major strike waves currently taking place in South Africa and several other countries.

In early 2014 platinum miners in South Africa held a five month all-out strike winning significant above-inflation pay increases for the next three years. Some of these miners had also taken part in the strike that involved the massacre of 34 of their colleagues at Marikana in August 2012. In July 2014 Numsa, the largest union in South Africa, won 10 percent wage increases for its lowest paid members for the next three years and above-inflation increases for its other members after a four-week strike.

In Nigeria, judiciary workers have been on strike in many states since the beginning of the year over independence for the courts and health workers ended their largely successful strike in early February. Last year a ten-month strike by polytechnic lecturers, inspired by an equally long and successful strike by university lecturers, ended in July. Public sector doctors struck for two months (ending in compromise due to disunity with other health workers); judicial workers were also on strike for three weeks, along with a host of local strikes including a five-day general strike in Benue State. During 2013 there had been major strikes by health workers and college lecturers with some lasting months. At the beginning of 2012 there was an almost insurrectional general strike against the removal of fuel subsidies. This succeeded in retaining at least some level of subsidy—essential for the travel costs of many workers across Nigeria.

The average per capita growth across sub-Saharan Africa over the last two decades has begun to make up for the significant decline experienced over the previous two decades. However, neoliberal reforms of privatisation and deregulation mean that the rich are currently receiving most of the benefits of this growth. This is in a situation where per capita incomes are still as much as 10 percent below the peak of the mid-1970s. Significant redistribution of wealth and incomes will be needed, in addition to continued economic growth, if the number of Africans living in abject poverty is to be reduced over the coming decades.

Political collapse and civil wars in the Central African Republic, Mali and South Sudan and continued insurgency in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and northern Nigeria, for example, indicate the barbarism that is possible where socialists and the organised working class are not able to provide an effective lead. Such risks are also possible around this year’s presidential election in Nigeria. Post-election violence conditioned by ethnic partisanship cannot be ruled out as an outcome of these elections. Whichever of the main contenders wins, the introduction of austerity measures, as part of the existing neoliberal policies, is set to continue and, unless the trade unions can lead a real fightback, this will make the lives of the mass of workers and other poor people worse.

The working class and its allies are now acting in many parts of the region to rebuild their strength and so try and reduce the increased levels of inequality and poverty that they have suffered since the early years of independence. There is a major wave of strikes and other protests in South Africa, Nigeria, Kenya and other countries across the region. This provides excellent conditions for building socialist organisations and the independent forces of the working class that will in turn be able to lead the further struggles that will be necessary for fundamental change.

Notes

1: Austin, 2010.

2: Saul and Leys, 1999.

3: Okigbo, 1993.

4: Saul and Leys, 1999.

5: Mkandawire and Soludo, 1999.

6: World Bank, 2012.

8: Boahen, 1990.

9: Abdulkadir, Jayum, Zaid and Asnarulkhadi, 2010.

10: UN Economic Commission for Africa and African Union, 2011.

11: World Bank figures, Iliffe, 2007.

12: World Bank figures, Iliffe, 2007.

13: World Bank figures, Iliffe, 2007.

14: IMF, 2013, and World Bank, 2013.

15: Artadi and Sala-i-Martin, 2003.

16: World Bank, 2013.

17: Artadi and Sala-i-Martin, 2003.

18: Saul and Leys, 1999.

19: UN Economic Commission for Africa and African Union, 2011.

20: Arrighi, 2002.

21: Harvey, 2005, p27.

22: Quoted in Harvey, 2005.

23: Mkandiwire and Soludo, 1999, p21.

25: Clark and Dilnot, 2002.

26: Mkandawire and Soludo, 1999.

27: Arrighi, 2002.

28: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, 2002, p138.

29: Christian Aid, 2003, p22.

30: World Bank, 1983.

31: Dwyer and Zeilig, 2012, p35.

32: Brown, 1995, p79.

33: World Bank, 1988, p24.

34: Amin, 2010.

35: Toyo, 1981.

36: Gelb, 2000.

37: Harvey, 2005.

38: Stiglitz, 2006.

39: Bond, 2006.

40: Moyo, 2009.

41: Arrighi, 2002, p24.

42: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, 2004, p5.

43: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, 2004.

44: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, 2004, p9.

45: Onimade, 2000.

46: Mazrui, 1999.

47: Moyo, 2009.

48: Saul and Leys, 1999.

49: UN Economic Commission for Africa, 2012.

50: Sender, 1999.

51: UN Economic Commission for Africa, 2012.

52: Elbadawi, Ghura and Uwujaren, 1992, p5.

53: Dollar and Svensson, 1999.

54: UN Economic Commission for Africa and African Union, 2011, pp102-103.

55: Iliffe, 2007.

56: Dwyer and Zeilig, 2012.

57: Slotterback, 2007.

58: Eneji, Onyinye, Kennedy, and Rong, 2012.

59: Aguiyi, Ukaoha, Onyegbulam, and Nwankwo, 2011.

60: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, 2012, pviii.

61: World Bank, 1989, p1.

62: Elbadawi, Ghura, and Uwujaren, 1992.

63: International Labour Organisation, 1990, p34.

64: Quoted in Brown, 1995, p265.

65: Saul and Leys, 1999.

66: Iliffe, 2006.

67: Ndikumana and Boyce, 2011.

68: Quoted in OECD/AfDB, 2011.

69: Loong, 2007; Shivji, 2009, p65.

70: Ndikumana and Boyce, 2011.

71: Ndikumana and Boyce, 2012.

72: Kapur and McHale, 2005.

73: Stewart, 1995, quoted in Mkandiwire and Soludo, 1999.

74: Mathiason, 2005.

75: Iliffe, 2007, p313.

76: Arrighi, 2002.

77: Abdulkadir, Jayum, Zaid, and Asnarulkhadi, 2010.

78: UNAIDS, 2010.

79: Jahan, 2003, p3.

80: Owusu and others, 2000.

81: UN Economic Commission for Africa, 2012.

82: Shivji, 2009.

83: Capps, 2005.

84: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, 2002.

85: UN Economic Commission for Africa and African Union, 2011.

86: UN Economic Commission for Africa, 2012, p59.

87: UN Economic Commission for Africa, 2012, p59.

88: UN Economic Commission for Africa and African Union, 2011.

89: World Bank, 2013.

90: IMF, 2013.

91: UN Economic Commission for Africa, 2012.

92: World Bank, 2013.

93: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, 2012, and World Bank, 2013.

94: African Development Bank, 2014.

95: World Bank, 2013.

96: World Bank, 2013.

97: African Development Bank, 2014.

98: World Bank, 2014.

99: African Development Bank, 2014.

100: Sun, 2014.

101: Chun, 2014.

102: African Development Bank, 2014.

103: World Bank, 2013.

104: World Bank, 2013, p12.

105: African Development Bank, 2013.

106: African Development Bank, 2013.

107: Kar and others, 2013.

108: African Development Bank, 2013.

109: UN Economic Commission for Africa and African Union, 2011, p75.

110: Shivji, 2009.

111: Namibian, 3 October 2012.

112: Alvaredo and Atkinson, 2010, IMF, 2013, and African Development Bank, 2013.

113: Di Paola and Pons-Vignon, 2013.

114: For example, Economic Commission for Africa, 2012, IMF, 2013 and World Bank, 2013.

115: World Bank, 2013, and IMF, 2013.

116: World Bank, 2013.

117: World Bank, 2013.

118: Filmer and Fox, 2014.

119: Onimode, 2000.

120: Shivji, 2009, and United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, 2012.

121: African Development Bank, 2013.

122: Filmer and Fox, 2014.

123: Filmer and Fox, 2014.

124: Di Paola and Pons-Vignon, 2013.

125: Aye, 2012.

126: Aye, 2012.

127: World Bank, 2012.

128: Aye, 2012.

References

Abdulkadir, M S, A A Jayum, A B Zaid, and A S Asnarulkhadi, 2010, “Africa’s Slow Growth and Development: An Overview of Selected Countries”, European Journal of Social Sciences, Volume 16, Number 4.

African Development Bank, 2013, “African Economic Outlook 2013: Structural Transformation and Natural Resources—pocket edition” (AfDB, OECD, UNDP, ECA), www.africaneconomicoutlook.org/fileadmin/uploads/aeo/PDF/Pocket Edition AEO2013-EN.web.pdf

African Development Bank, 2014, “African Economic Outlook 2014: Global Value Chains and Africa’s Industrialisation” (ADB, OECD and UNDP).

Aguiyi, Godswill, Ken Ukaoha, Lilian Onyegbulam and Onyekachi Nwankwo, 2011, “The Comatose Nigerian Textile Sector—Impact on Food Security and Livelihoods” (National Association of Nigerian Traders).

Alvaredo, Facundo, and Anthony B Atkinson, 2010, “Colonial Rule, Apartheid And Natural Resources: Top Incomes in South Africa, 1903-2007”, Discussion Paper number DP8155 (Centre for Economic Policy Research), http://topincomes.g-mond.parisschoolofeconomics.eu/#Country:South%20Africa

Amin, Samir, 2010 [1978], The Law of WorldWide Value (Monthly Review Press).

Arrighi, Giovanni, 2002, “The African Crisis—World Systemic and Regional Aspects”, New Left Review, II/15 (May-June), http://newleftreview.org/II/15/giovanni-arrighi-the-african-crisis

Artadi, Elsa, and Xavier Sala-i-Martin, 2003, “The Economic Tragedy of the XXth Century: Growth in Africa”, National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper W9865, www.econ.upf.edu/docs/papers/downloads/684.pdf

Austin, Gareth, 2010, “African Economic Development and Colonial Legacies”, International Development Policy Series, http://poldev.revues.org/78

Aye, Baba, 2012, Era of Crises & Revolts—Perspectives for Workers and Youths (Solaf Publishers).

Boahen, A Adu (ed), 1990, General History of Africa Volume VII: Africa under Colonial Domination 1880-1935 (UNESCO).

Bond, Patrick, 2006, Looting Africa: The Economics of Exploitation (Zed Books).

Brown, Michael Barratt, 1995, Africa’s Choices: After Thirty Years of the World Bank (Penguin Books).

Capps, Gavin, 2005, “Redesigning the Debt Trap”, International Socialism 107 (summer), http://isj.org.uk/redesigning-the-debt-trap/

Christian Aid, 2003, The Trading Game: How Trade Works (Oxfam).

Chun, Zhang, 2014, “The Sino-Africa Relationship: Toward a New Strategic Partnership” (London School of Economics IDEAS reports).

Clark, Tom, and Andrew Dilnot, 2002, “Measuring the UK Fiscal Stance Since the Second World War”, The Institute for Fiscal Studies Briefing Note Number 26.

Di Paola, Miriam, and Nicolas Pons-Vignon, 2013, “Labour Market Restructuring in South Africa: Low Wages, High Insecurity”, Review of African Political Economy, Volume 40, number 138.

Dollar, David, and Jakob Svensson, 1999, “What Explains the Success or Failure of Structural Adjustment Programs?” (World Bank Policy Research Working Paper).

Dwyer, Peter, and Leo Zeilig, 2012, African Struggles Today (Haymarket).

Elbadawi, Ibrahim A, Dhaneshwar Ghura, and Gilbert Uwujaren, 1992, “World Bank Adjustment Lending and Economic Performance in Sub-Saharan Africa in the 1980s: A Comparison with Other Low Income Countries” (World Bank Policy Research Working Paper).

Eneji, Mathias Agri, Iwayanwu J Onyinye, Drenkat N Kennedy, and Shi Li Rong, 2012, “Impact of Foreign Trade and Investment on Nigeria’s Textile Industry: The Case of China”, Journal of African Studies and Development, volume 4, number 5, www.academicjournals.org/article/article1380034520_Eneji%20et%20al.pdf

Filmer, Deon, and Louise Fox, 2014, “Youth Employment in Sub-Saharan Africa: Volume 2” (World Bank Africa Development Forum Series).

Gelb, Alan H, 2000, Can Africa Claim the 21st Century? (World Bank).

Harvey, David, 2005, A Brief History of Neoliberalism (Oxford University Press).

Iliffe, John, 2006, The African Aids Epidemic: A History (Ohio University Press).

Iliffe, John, 2007, Africans: The History of a Continent: 2nd edition (Cambridge University Press).

IMF, 2013, “Regional Economic Outlook: Sub-Saharan Africa”, www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/reo/2013/afr/eng/sreo1013.htm

International Labour Organisation, 1990, “African Employment Report 1990”.

Jahan, Selim, 2003, “Financing Millennium Development Goals—An Issues Note” (conference paper), http://r4d.dfid.gov.uk/PDF/Outputs/ChronicPoverty_RC/Jahan.pdf

Kapur, Devesh, and John McHale, 2005, Give Us Your Best and Brightest: The Global Hunt for Talent and Its Impact on the Developing World (Center for Global Development).

Kar, Dev, Sarah Freitas, Jennifer Mbabszi Moyo, and Guirane Samba Ndiaye, 2013, “Illicit Financial Flows and the Problem of Net Resource Transfers from Africa: 1980-2009” (Global Financial Integrity and African Development Bank), http://africanetresources.gfintegrity.org/index.html

Loong, Yin Shao, 2007, “Debt: The Repudiation Option” (Third World Network), http://finance.thirdworldnetwork.net/article.php?aid=47

Mazrui, Ali A (ed), 1999, General History of Africa Volume VIII: Africa since 1935 (UNESCO).

Mkandawire, Thandika, and Charles C Soludo (eds), 1999, Our Continent, Our Future: African Perspectives on Structural Adjustment (Codesria).

Moyo, Dambisa, 2009, Dead Aid: Why Aid Is Not Working and how there is A Better Way for Africa (Penguin).

Ndikumana, Léonce, and James Boyce, 2011, Africa’s Odious Debts—How Foreign Loans and Capital Flight Bled a Continent (Zed).

Ndikumana, Léonce, and James Boyce, 2012, “Capital Flight from Sub-Saharan African Countries: Updated Estimates 1970—2010” (Political Economy Research Institute), www.peri.umass.edu/236/hash/d76a3192e770678316c1ab39712994be/publication/532/

Mathiason, Nick, 2005, “Consultants Pocket $20bn of Global Aid”, Observer (29 May), www.theguardian.com/business/2005/may/29/hearafrica05.internationalaidanddevelopment

OECD/AfDB, 2011, “African Economic Outlook 2011: Africa and its Emerging Partners”, www.afdb.org/en/knowledge/publications/african-economic-outlook/african-economic-outlook-2011/

Okigbo, Pius, 1993, “Problem, Crisis, or Catastrophe: Any Exit for African Economies in the 1990s?” in Nigerian National Merit Award Lectures, volume 3 (Fountain Publications).

Onimode, Bade, 2000, Africa In the World of the 21st Century (Ibadan University Press).

Owusu, Kwesi, Sarah Clarke, Stuart Croft, and John Garrett, 2000, “Through the Eye of a Needle: The Africa Debt Report” (Jubilee 2000 Coalition).

Saul, John S, and Colin Leys, 1999, “Sub-Saharan Africa in Global Capitalism”, Monthly Review (July/August), http://monthlyreview.org/1999/07/01/sub-saharan-africa-in-global-capitalism/

Sender, John, 1999, “Africa’s Economic Performance: Limitations of the Current Consensus”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, volume 13, number 3.

Shivji, Issa G, 2009, Accumulation in an African Periphery—a Theoretical Framework (Mkuki na Nyota Publishers).

Slotterback, Jamie N, 2007, “Threadbare: The Used-clothing Trade and its Effects on the Textile Industries in Nigeria and other Sub-Saharan African Nations” (seminar paper).

Stiglitz, Joseph, 2006, Making Globalization Work (Allen Lane).

Sun, Yun, 2014, Africa in China’s Foreign Policy (Brookings).

Toyo, Eskor, 1981, Primary Accumulation and Development Strategy in a Neo-colonial Economy—A Critique of Dependence Theory and its Implications (publisher unknown).

UNAIDS, 2010, “UNAIDS Report on the Global Aids Epidemic”, www.unaids.org/globalreport/Global_report.htm

UNCTAD, 2002, “The Least Developed Countries Report 2002: Escaping the Poverty Trap” (United Nations), www.unctad.org/en/docs/ldc2002_en.pdf

UNCTAD, 2004, “Economic Development in Africa: Debt Sustainability: Oasis or Mirage?” (United Nations), http://unctad.org/en/docs/gdsafrica20041_en.pdf

UNCTAD, 2012, “Policies for Inclusive and Balanced Growth” (United Nations Trade and Development Report), http://unctad.org/en/publicationslibrary/tdr2012_en.pdf

UNECA and African Union, 2011, “Economic Report on Africa 2011—Governing Development in Africa—The Role of the State in Economic Transformation”, www.nepad.org/system/files/UNECA%20Economic%20Report%20content%20EN_final_WEB.pdf

UN Economic Commission for Africa, 2012, “Economic Report on Africa 2012—Unleashing Africa’s Potential as a Pole of Global Growth” (UNECA and African Union), www.uneca.org/sites/default/files/publications/era2012_eng_fin.pdf

World Bank, 1983, World Development Report 1983 (Oxford University Press).

World Bank, 1988, World Development Report 1988: Public Finance in Development (Oxford University Press).

World Bank, 1989, Sub-Saharan Africa: From Crisis to Sustainable Growth (World Bank).

World Bank, 2012, “Global Economic Prospects January 2012: Uncertainties and Vulnerabilities” (World Bank), http://tinyurl.com/ogn5oo2

World Bank, 2013, “Africa’s Pulse: An Analysis of Issues Shaping Africa’s Economic Future: Volume 8” (October) (World Bank), www.worldbank.org/content/dam/Worldbank/document/Africa/Report/Africas-Pulse-brochure_Vol8.pdf

World Bank, 2014, “Africa’s Pulse: an analysis of issues shaping Africa’s economic future: Volume 9” (April), (World Bank), www.worldbank.org/content/dam/Worldbank/document/Africa/Report/Africas-Pulse-brochure_Vol9.pdf