For a timeline of key events related to this article go to http://isj.org.uk/pakistan-timeline-of-key-events

The popular image of Pakistan is of a failing state with nuclear weapons. Neither the government nor the army can prevent the Taliban’s terrorist outrages, not least because they cannot do without the proxy forces they use against Afghanistan and India, forces often indistinguishable from the Taliban in their methods. What follows seeks to show the falsity of this pathologising, Islamophobic mythology that pays little attention to Pakistan’s place in the global division of labour. It applies an understanding of imperialism as the combination of the unequal competition between capitals and the geopolitical conflicts between states aiming to show that the core elements of Pakistan’s crisis are not unique to Pakistan but result from dynamics which always produce uneven results.

Our starting point is the world economy. With global economic growth slow and without a full recovery from the 2008 crash, despite record stock market highs, Pakistan’s annual growth, at just over 4 percent, barely keeps GDP per head rising. Growth of 7 percent is needed to absorb the annual 2 million increase in the labour force. The resultant poverty for most of its 180 million people, half of them under 25, is not specific to Pakistan. Rather, as Karl Marx put it, “an accumulation of misery [is] a necessary condition, corresponding to the accumulation of wealth”.1 But why is Pakistan’s performance so weak when compared to most of South and East Asia? The argument that imperialism has underdeveloped Pakistan as some form of neo-colony is mistaken.2 The reasons for Pakistan’s failure to join the Asian tigers do not lie in unmediated North on South pressures from the heart of the beast, depriving Pakistan of access to productive resources.3 Rather the explanation lies in the failure of the Pakistan bourgeoisie to establish its territory as a location for successful accumulation in a world dominated by competing global capitals. Unlike India and South Korea, it has failed to establish its own multinationals. This is despite the geopolitical advantages it possesses with major powers competing to strengthen their influence.

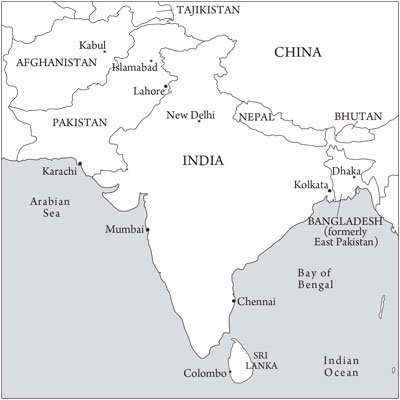

Pakistan and surrounding countries

Pakistan’s colonial legacy

It is true that the early stages of capitalism as a global system, the primitive accumulation of capital, saw the Indian subcontinent robbed of greater wealth than anywhere else.4 The destruction of much of its textile industry in the 18th and 19th centuries created a huge, captive market for British exports. Yet under imperial domination of the world’s most valuable colony there was a willingness to develop selected productive capacity in the Indian subcontinent.5 Arguably the most important example was the expansion of the Indus irrigation system in Punjab. Today it is the world’s largest, valued at $300 billion.6 Securing the north western border with Afghanistan against the expanding empire of the Russian tsars, the so-called “Great Game”, was an important element of British imperial strategy.

The British used a peculiarly sharp form of divide and rule in creating “Muslim” Pakistan in 1947. Partition, the division of the subcontinent, came at the cost of over a million lives. Pakistan was based on the large landowners of Punjab and, on the opposite side of the subcontinent, the privileged few of East Bengal in what would later become independent Bangladesh.7 Together with the mohajirs, educated migrants from northern India, they saw the opportunities to be gained from creating their own state. The result was a truncated state dominated by mohajir and Punjabi elites who oppressed all other nationalities including Sindhis, Pashtuns, Balochis and Bengalis economically, politically and culturally. The need to have India as a threat that justified Pakistan’s existence guaranteed that throughout the Cold War the subcontinent would never unite against the US and its allies. In two halves on opposite sides of the subcontinent separated by a thousand miles of hostile territory, starting with just 9 percent of the industry and virtually none of the banks that had existed in previously united India, Pakistan would always struggle to compete.

The first Asian tiger?

Despite this, Pakistan boosted its annual growth from 3.5 percent in the 1950s to 6.5 percent in the 1960s, overall a higher rate than India. Unlike India, as a loyal servant of Western imperialism Pakistan received substantial US military and civilian aid. It was, however, not its political loyalties that qualified it as the first Asian “tiger”: “Many countries sought to emulate Pakistan’s economic planning strategy and one of them, South Korea, copied its second Five Year Plan, 1960-65. In the early 1960s the per capita income of South Korea was less than double that of Pakistan”.8

The post-war boom provided a global market in which, with strong support from the state, capital intensive industry expanded rapidly. Starting as joint public-private ventures they were handed to private owners when they became viable. In effect, a new manufacturing bourgeoisie was created by the state.9 Such state-driven hothousing of economic growth was not unique to Pakistan. What distinguished it was the government’s pro-market attitude, particularly under its first military dictator, Ayub Khan. Pakistan welcomed advice from Gustav Papanek and other Harvard academics advocating “the social utility of greed”.10 While manufacturing output grew at an annual rate of 10 percent,11 real wages were kept down, both by squeezing agriculture to lower food prices and by repressing labour organisation. The share of wages in value added in manufacturing fell from 45 percent in 1954 to 25 percent in 1967.12 A number of private business groups, often called “the 22 families”, came to dominate manufacturing, insurance and finance.13

The uneven geographical distribution of growth was politically unsustainable. Trying to deal with this, in particular to forestall any electoral victory for Bengalis, who constituted 55 percent of the total population, the “One Unit” policy in 1955 combined the four provinces of West Pakistan into one with its capital in Lahore, Punjab’s largest city. East Bengal became “East Pakistan”. Land ownership was skewed in favour of rich farmers whose power grew as land reform failed. Often called “feudals”, the persistence of the term conveys their brutal control at the local level.

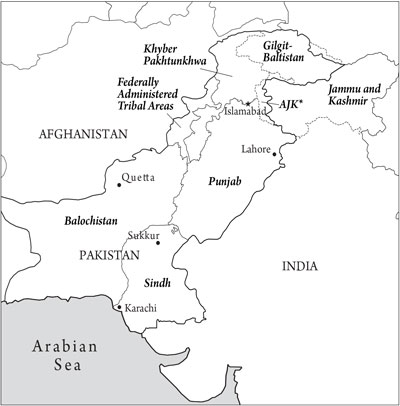

Regions of Pakistan

*AJK= Azad Jammu Kashmir, under control of Pakistan. Dashed lines denote disputed territories.

Not only were the benefits of growth unequally divided between classes14 but East Pakistan was treated almost as a colony of West Pakistan. The lion’s share of growth went to Karachi, Lahore, Faisalabad and the other big cities of Punjab and Sindh. As industry in these cities grew, so did slums which housed half of Pakistan’s urban population. Education, health services, public transport and welfare provision all failed to keep pace. Sustained repression of workers included shooting striking workers during the Karachi mass strike of March 1963.

By 1968 the masses had had enough of “managed democracy”. Students and workers rose against the regime and within four months Ayub Khan had gone, opening the way to the country’s first proper general election in 1970 with an overwhelming victory for Bengali nationalists in East Pakistan. The army under Ayub Khan’s successor, Yahya Khan, responded with genocidal repression which cost more lives than partition but was unable to avoid humiliating defeat at the hands of India. In December 1971 East Pakistan became Bangladesh. What was left, West Pakistan, found itself bankrupt.

The state capitalist alternative

As with all developing countries, the global recession of 1973-74 found Pakistan in a weak position to overcome the end of the post-war boom. Promoting a “third world” model of development which inspired radical nationalists in former colonies across the globe, Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, then a reformist politician, built a populist mass base, the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP). He campaigned for working class and poor peasant votes using the slogan “Bread, clothing and shelter” and won the 1970 general election in West Pakistan. Taking office as president in December 1971, he vigorously pursued a Nasserite state capitalist strategy,15 immediately nationalising 31 major industrial enterprises, including steel, chemicals and cement and fertiliser plant. Three years later he followed this with nationalisation of banking, insurance and shipping. Bhutto’s more radical attempt at land reform failed as badly as its predecessors. While workers used new tactics such as gherao, occupying the workplace with the boss held captive in his office, Bhutto, much weakened by the loss of East Pakistan and unable to sustain the new social contract with the poor, the oppressed nationalities and women, turned on the radicals. A key turning point came in the Karachi textile mills, June-October 1972, where a mass strike and three month long occupation of working class communities with workers killed by police both in June and October ended with defeat for the workers.16

A large Sindhi landlord himself, Bhutto made alliances with the rich to bolster his position. Faced with quadrupled oil prices, he sought backing from Saudi Arabia by playing the “Islam card”. In 1974 he declared the million strong Ahmadi sect to be “un-Islamic” and three years later banned alcohol, made Friday an official holiday and shut down much of the cultural life in cities. General Zia-ul-Haq, a staunch Islamist, was appointed army chief of staff. Having attacked the radical base that had worked to bring him to power and strengthened the repressive apparatus, with an army chief who, unlike himself, was committed to an Islamist worldview, Bhutto had paved the way for Zia to depose him in a right wing coup. While there was no Chile-style involvement by the US, there was unofficial approval of Zia’s takeover in July 1977.17 Zia introduced elements of sharia law, sharpening sectarianism, but made no immediate changes in economic policy. Political parties together with labour unions and student unions were suppressed, journalists were flogged for criticising the dictatorship and party-less elections held, initially for local bodies, later in 1985 for national and provincial assemblies. A new layer of subservient “non-party” politicians were brought in.

Neoliberalism

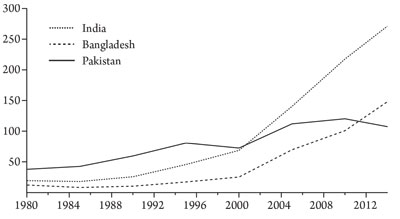

Despite the growth achieved by Bhutto under difficult circumstances—the average rate in the 1970s, 4.8 percent, was higher than that in the 1950s—Zia came to accept the “Washington Consensus” over privatisation and deregulation, deficit reduction and trade liberalisation. The neoliberal “reforms” under Zia started slowly with roll-back measures to restore the private sector. By 1988, when Zia was killed in an air crash, the public sector share of total industrial investment had fallen from 73 to 18 percent. Though growth averaged over 6 percent, exports per capita stagnated (see figure 1). The interim government appointed by the military and headed by former IMF employees signed the structural adjustment agreements focused on reducing budget deficits and boosting currency reserves.

Figure 1: Exports of goods and services per capita 1980-2014 (in constant 2005 US dollars)

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators

These agreements set the course for the next decade. While the Asian tigers used state control to accumulate capital to bring “the end of the Third World”,18 Pakistan failed to keep pace. This was not because of external pressures, real as these were, but from a failure to use resources to accumulate and compete for a larger share of the world market. Instead the resources gained from its geopolitical situation, an (unpredictable) rentier benefit, paid for the coercion needed to sustain control. The resulting position of the army with its hegemonic political role has reduced parties to little more than organised patronage. While investment in education, research, health and welfare remains minimal, the political class focuses on dividing the spoils.

The depth of ethnic division and lack of any Pakistani national ideology beyond seeing India as the eternal enemy have made a strong military necessary if Pakistan is to survive as a single entity. The success of Bengali nationalists in breaking away in 1971 inspires Baloch, Pashtun and Sindhi nationalists. It makes the myth of India as a permanent threat indispensable.

The International Monetary Fund

Pakistan’s relation to neoliberal imperialism has not been one of subservience. Foreign multinationals play a limited role. Rather IMF loans have been used to postpone and ultimately avoid the reforms that they were designed for. Since 1988 Pakistan has had 12 IMF programmes, more than all other South Asian countries combined. None have succeeded in reducing the budget deficit or increasing the tax base. Pakistan still has a tax to GDP ratio of less than 9 percent, half that of India and a quarter of the OECD average. The rich evade paying tax; and the military takes 35 percent of the budget. Throughout the 1990s exports hardly grew and development expenditure fell with a growing layer of aid-funded NGOs in a quasi welfare state role. Support for foreign reserves came not from increased exports but from loans that continued thanks to US fears of civil breakdown in Pakistan (as happened in Sudan after the IMF withdrew).

Thus IMF programmes not only failed to bring reform but acted as a shield protecting Pakistan’s ruling class from the need to reform. Today a combination of unilateral US, European Union and Saudi aid plus IMF and World Bank programmes provide what can be called “geopolitical rent”. The current IMF programme provides $6.7 billion, paid in quarterly tranches. Through the 1990s Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) and Muslim League governments, relying on IMF loans, presided over growth averaging little more than 4 percent. There was little difference between the PPP, led by Bhutto’s daughter Benazir with a popular base in the cities plus backing from Sindhi feudals, and Nawaz Sharif’s Muslim League (PML-N), party of the big bourgeoisie and landlords.

From General Pervez Musharraf’s 1999 military coup to the collapse of the global boom in 2008, growth averaged 7 percent per year—without, however, Pakistan catching up on its competitors. The government debt burden fell; the IMF programmes stopped. As elsewhere, this was credit-fuelled expansion. The middle class grew along with consumer debt. The banks were given the largest interest rate spread in the world, much of their lending contributing to a property bubble. Speculators hoarded sugar, flour and rice whose prices jumped. Mobile phone use grew exponentially and private TV channels flourished, neither having much impact on labour productivity. This was a joyless boom with little improvement in most people’s living standards and none in Pakistan’s competitiveness.

As the officer class enriched itself, Musharraf, both military chief and president, found himself increasingly challenged by the judiciary. In suspending the chief justice of the Supreme Court, Iftikhar Chaudhry, in March 2007, he triggered a wave of protests led by lawyers against the growing corruption and incompetence of his dictatorship. Baton charging the protests only radicalised the movement, which climaxed with the elections in early 2008 replacing Musharraf with PPP boss Asif Zardari, husband of the assassinated Benazir Bhutto. Under Zardari, government borrowings rose by 10.3 trillion Pakistani rupees ($100 billion), pushing debt up to 68 percent of GDP. His successor from 2013, Nawaz Sharif, has taken $32 billion in loans from China, $11 billion from the World Bank, $6.64 billion from the IMF and $2 billion in eurobonds.

Efforts to boost tax revenues to overcome the low income tax to GDP ratio have done nothing to reduce tax evasion, only increasing the burden on the poor with indirect tax revenue nearly twice that from direct taxation.19 Meanwhile, despite extensive borrowing, load-shedding—power cuts of six hours daily in big cities and up to 22 hours in rural areas—continues as electricity production lags 25 percent behind demand, up to 60 percent in summer. Unregulated development leading to pollution and the destruction of the environment is the norm. Dams and the manipulation of irrigation systems were important contributors to catastrophic flood damage that has destroyed the livelihoods of several million people since 2010.

Labour rights are weaker than under the British. Some 95 percent of Sindh’s 14 million workers are unregistered with no entitlement to social security benefits. There is no enforcement mechanism for the minimum wage. Labour inspectors in Punjab and Sindh have not set foot in a factory for more than 10 years. The owners of the Ali Enterprise clothing factory in Karachi, where locked fire doors led to the death of over 250 workers in September 2012, had no record of the names of most of the thousand workers in the plant when the fire started. They were hired on casual contracts by a senior manager acting as an employment agency. Inflation, averaging 8 percent, robs the poor. The official figure for August 2015, 1.7 percent, is a 12-year low. The effective rate for those spending over half their income on food is higher.20 The worsening figures for stunted growth in children under five indicate that increases in the rate of exploitation undermine the capacity of labour power to reproduce.21

Accumulate, accumulate!

Support for export-led growth had to focus on textiles, Pakistan’s most important industry, today employing 15 million workers, 30 percent of the industrial workforce, and producing just under 10 percent of GDP. With global exports of textiles and clothing around $600 billion, Pakistan is a relatively minor player with exports of $13 billion in 2014 (table 1). Its textile industry, untrammelled by regulation, paying male workers less than Rs12,000 a month (£80) for a 53-hour week and female workers Rs6,900,22 competes with that of Bangladesh, Vietnam and Cambodia in the race to the bottom (see table 1). Given Pakistan’s position as the world’s fourth largest producer of raw cotton there is a clear failure to make the downstream investment needed fully to exploit the value added potential of this crop, much of which is exported as yarn or semi-finished cloth, often of poor quality. This is despite the capital needed to expand the clothing industry being far less than the current investment in large-scale spinning and weaving plant, much of it concentrated in large integrated plants, with up to 20,000, mainly male, workers. The clothing industry is relatively labour intensive, generally in much smaller units with vast and growing numbers of subcontractors, often home based women paid lower wages. Expanding it would require investment in a more skilled workforce in the increasingly sophisticated supply chain for clothing exports across the globe.

Table 1: Clothing exports of selected economies (million dollars)

Source: World Trade Organisation, 2014.

|

|

1990 |

2000 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

|

World |

108,129 |

197,635 |

417,724 |

422,573 |

460,268 |

|

Bangladesh |

643 |

5,067 |

19,214 |

19,788 |

23,501 |

|

Cambodia |

— |

970 |

3,995 |

4,294 |

5,095 |

|

China |

9,669 |

36,071 |

153,774 |

159,614 |

177,435 |

|

India |

2,530 |

5,965 |

14,672 |

13,833 |

16,843 |

|

Indonesia |

1,646 |

4,734 |

8,045 |

7,524 |

7,692 |

|

Malaysia |

1,315 |

2,257 |

4,567 |

4,560 |

4,586 |

|

Pakistan |

1,014 |

2,144 |

4,550 |

4,214 |

4,549 |

|

Sri Lanka |

638 |

2,812 |

4,211 |

4,005 |

4,511 |

|

Turkey |

3,331 |

6,533 |

13,948 |

14,290 |

15,408 |

|

Viet Nam |

— |

1,821 |

13,149 |

14,443 |

17,230 |

Industry’s failure to invest in fixed capital can, in the first instance, be explained by a gross national saving rate of 13 percent compared to India’s 34 percent, Bangladesh’s 30 percent and China’s 50 percent.23 Pakistan’s annual foreign direct investment (FDI) is only $1.5 billion ($8 per capita) and its total FDI is $24.33 billion—India’s is 12 times as much, $310 billion. The problem is not too much foreign control of Pakistan but too little investment. One important reason is the energy crisis. Another is the law and order situation in Karachi, Pakistan’s largest industrial centre. There are reports of textile plant relocating to Bangladesh.24 The resulting weak growth creates vicious circles. With few jobs being created, labour migrates abroad, particularly to the Gulf. Betweem 2008 and 2013 some 2.5 million workers left, many skilled, a brain drain weakening Pakistan as an investment location and reinforcing dependence on foreign aid and remittances from expatriates. Running at $15 billion a year, these remittances are indispensable in paying for much of Pakistan’s imports.

The stick of “open door” imperialism continues with the occasional carrot such as the European Union’s 2013 decision to grant Pakistan trade concessions conditional on progress with human rights and ILO conventions. The 20 percent increase in textile exports to the economically stagnant EU, Pakistan’s largest export market, in the first eight months of 201525 shows the EU’s softer strategy compared to that of the US. It illustrates how states and their representative institutions such as the EU, however much they are influenced by multinational corporations, dominate economic development.

An Islamic state?

Hamza Alavi’s concept of the relatively autonomous “overdeveloped state” in “such peripheral capitalist societies as Pakistan”26 implies a self-perpetuating burden condemning Pakistan to permanent domination—sometimes open, sometimes hidden—by the military. But Pakistan did not inherit an overweight state apparatus from the British, quite the opposite. Rather, the various forms of “strong” state in Pakistan are rooted in partition and the consequent need for a vast military to deal with India.

It was this weakness of the Muslim landowners that led to Muhammad Jinnah’s adoption of a “two nations, Muslims and Hindus” theory to justify dividing the subcontinent. Jinnah’s use of religion was, however, very soft. Pakistan was not an Islamic state:

Islam and Hinduism are not religions in the strict sense of the word, but in fact different and distinct social orders, and it is only a dream that the Hindus and Muslims can ever evolve a common nationality… To yoke together two such nations under a single state…must lead to a growing discontent and final destruction of any fabric that may be so built up for the government of such a state.27

It was, however, impossible to show that life for Muslims in Pakistan was better than in India. In 1953 there was rioting in Punjab with Ahmadi sect members targeted as “non-Muslims”. Bangladesh’s secession left Pakistan with only a third of the subcontinent’s Muslims. Consequently the ongoing efforts by governments to reinforce the “Muslim identity”, school syllabuses shaping the common sense of the young, can only be understood as “playing the Muslim card”.28 While Jinnah insisted that Pakistan “should be a modern democratic state with sovereignty resting in the people and the members of the new nation having equal rights of citizenship regardless of their religion, caste or creed”,29 others argued the state should be based on sharia law. Pakistan’s successive constitutions contained compromises reflecting politicians’ alliances with religious forces, forces that have rarely been electorally successful. The judgement of the Supreme Court’s sharia bench that land reform contradicts Islam continues to reinforce the power of landlords. Despite assurances given over the years to minorities, Bhutto declared in 1974 that Ahmadis were not Muslim, boosting sectarianism, not just against Ahmadis but also against Shia, Hindu and Christian minorities. The 1977 ban on un-Islamic practices such as drinking alcohol laid the ground for Zia to introduce the Hudood ordinances, which enshrined sharia-based discrimination against women into law.

The growing strength of Islamist organisation has reached the point where any move towards secularism risks a violent response. Despite the links between terrorist activity and thousands of madrassas with several million students, funded both locally and by rich Sunni interests in the Gulf, commitments to regulate madrassas remain verbal. The key Islamist organisations are used by the deep state, ie the military intelligence agency, Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), which gives the Islamists the freedom to spread their networks. In return they can be employed to provide proxy forces in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir, Asad Jammu and Kashmir (AJK) and elsewhere.

The national question

Underlying the contradictions of the Islamic Republic is the national question. Conflicts between the four provinces have grown. Punjab, with over half of Pakistan’s population, benefits at the expense of the others. The majority of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK)30 was opposed to the partition of India in 1947 only to be forced to join Pakistan. Balochistan, the largest and poorest province, was only incorporated into Pakistan after invasion in 1948. Since then the state responds brutally to nationalist resistance with daily “disappearances” of activists whose bodies are often later found mutilated.31 Almost none of Balochistan’s gas and other natural resources have been used to develop the province. Sindh, the only province in West Pakistan with majority support for the Muslim League before 1947, quickly experienced discrimination in the distribution of resources. The recent 18th constitutional amendment, devolving education, labour, etc to provincial governments, is undermined by “apex committees”, ostensibly established to speed implementation of the counter-terrorism National Action Plan (NAP), and unable to correct the imbalances.

The army’s control of the deep state has combined with the corrupt practices of big business to hollow out the state’s formal structures. A coterie comprising army chief Raheel Sharif, his five corps commanders, prime minister Nawaz, his brother Shahbaz Sharif, chief minister of Punjab and Ishak Dar, minister of finance, make all the important decisions. The current priority is the domestic “war on terror”. But this has to be balanced with defence against the traditional enemy, so as the perceived threat level from India rises and falls, policy zigzags back and forth. The massacre at the Army Public School in Peshawar in December 2014 brought renewed commitment to the “war on terror”, to be followed a month later by concern that the defence posture towards India needed strengthening with Barack Obama’s India visit. It is not only that the resources to do both at once are not available but that they contradict each other. Defence against India involves strengthening precisely those Islamist organisations such as Jamaat-ud-Dawa and the Haqqani network that are the enemy in the “war on terror”. Unable directly to confront the vastly superior Indian forces, Pakistan has, since the 1990s, used these organisations as proxies. This sustains the myth of an ongoing challenge to India’s 68-year occupation of Kashmir and provides some control of the Afghan border needed to make “strategic depth” possible. At the same time the proxies’ jihadist ideology leads them to challenge the Pakistani state, often violently, whenever it looks for an accommodation with Indian or Afghan governments.

The army is caught in this contradiction. Since both religion and nation have to be used to justify their position, India must remain the enemy. Inevitably, India’s reaction is to expand its own military capacities, especially nuclear, creating an arms race draining the resources available for productive investment. This squeezes health, education and welfare spending. Pakistan spends 2.5 percent of GDP on education, India 3.9 percent, South Korea 4.6 percent.32

Despite having lost all the wars it has fought with India, the army describes itself as “the guardians of the geographical and ideological frontiers of the nation”. The confrontation with India over Kashmir, cause of three wars, remains unresolved. The “strategic depth” policy, the control of the Afghan border area, the army’s rear in any future conflict with India, necessitates good relations with the Afghan Taliban. Meanwhile, the proxy forces used in Afghanistan and Indian-occupied Kashmir, irregular Islamist militants, anti-Hindu and often anti-Shia, have spread across the country, often based in madrassas. Some carry out sectarian killings against “non-Muslims” such as the large Shia minority, and others have joined the Pakistani Taliban, though often only on a temporary basis, dependent on shifting tribal alliances and who is providing funding. Despite increasingly violent blowback, the military argues the only alternative is to admit defeat and accept a junior partnership position with India.

The US versus China

Pakistan depends on competition between rival imperialisms. After 1947, countering India’s good relations with Russia, the US-Pakistan alliance was underpinned with aid.33 This vital component of the economic boom of the 1960s was withdrawn after Pakistan’s attack on India in 1965. Relations with the US further worsened in the 1970s with Bhutto’s state capitalism, his anti-imperialist rhetoric and the decision to develop nuclear weapons. Following the Russian invasion of Afghanistan in 1980, Pakistan was a key US ally funnelling US aid to the mujahideen fighting the Russians. However, the collapse of the USSR and Pakistan’s nuclear weapons programme caused US aid to fall to an all-time low in the 1990s, relations cooling further when General Musharraf’s coup in 1999 established Pakistan’s third military dictatorship. Immediately after 9/11 US deputy secretary of state Richard Armitage invited Musharraf to be an ally in the “war on terror”, threatening to bomb Pakistan back to the Stone Age if the invitation was refused.

Since then assistance, mainly military, has fluctuated along with US perceptions of the terrorist threat. Anti-US sentiment in Pakistan has increased with the assassination of Osama Bin Laden, deaths of civilians caused by US drones and a CIA agent shooting two men dead on the streets of Lahore. Aid nevertheless continues at around $1.5 billion a year as the US seeks to maintain its credibility in the region after defeat in Iraq and Afghanistan and the rise of Islamic State. For Pakistan the price of US aid is high. The decision in June 2014 to attack North Waziristan, stronghold of the Pakistani Taliban and also a refuge for many foreign Islamist militants, has cost $1.9 billion creating 80,000 casualties and a million refugees. Far from defeating the enemy, Taliban activity has increased across Pakistan.

The often tense relations with the US contrast strongly with Pakistan’s joint ventures with China including airports and two nuclear power stations near Karachi and the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, new investments estimated at $46 billion. A new port at Gwadar, built and managed by China, will give China access to the Arabian Sea and all points west, cutting out the need for the long, vulnerable route round South East Asia through the Malacca Straits. These projects draw on around $40 billion in soft loans from the world’s largest creditor. China has earned the title of Pakistan’s “all-weather friend”, avoiding the rancour so often found in US-Pakistan relations.

Taliban, resistance of the rural poor and the “war on terror”

The British Raj had established a system of control by the maliks, the propertied class, in the settled areas of today’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA). This was reinforced with regulations allowing government agents to use force including collective punishment. Starting in the 1960s, the maliks’ authority was undermined by mass emigration to Karachi and later to the Gulf. In Karachi, Pashtun businesses came to dominate transport and construction. Together with the advantage of some modern education, the power of émigré remittances produced a challenge to traditional authority.

The Russian invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 was the key event in the decay of the power of the maliks. Some 35,000 young Muslims from across the world came to fight. They revived the tradition of a challenge from below, movements led by low status mullahs, often charismatic figures. They drew strength from the growing reputation of Islamism, the successful mujahideen challenge to the “socialist” regime in Kabul and its Russian “communist” backers and the Iranian Revolution’s overthrow of the Shah’s pro-US regime.

After 9/11, under pressure from the US, Pakistan, now “a key non-NATO ally”, sent 80,000 troops to fight fleeing Taliban. The question was whether to sustain the policy of strategic depth and relations with the Taliban or support the “war on terror”. The answer was to allow Taliban forces such as the Haqqani network to escape capture while continuing to publicise unverified “successes” in anti-terrorist operations. Good relations with the Afghan Taliban, however, also required some kind of relationship with the emerging Pakistani Taliban after the army’s invasion of Waziristan in the tribal areas in 2004 started the “Talibanisation” of Pashtun communities. These communities had strongly reacted against the breach of the agreement dating back to the Raj whereby the military stayed outside tribal areas. Resistance grew, strengthened in response to the US’s use of drones. From 2006 the Taliban marginalised tribal leaders, killing hundreds and forcing others to flee. The main Pakistani Taliban organisation, Tehrik-i-Taliban (TTP), was established in December 2007. As malik rule weakened, the army tried to build alliances with warlords, distinguishing between “good Taliban” and “bad Taliban”.

Efforts to restore support for central and provincial government among Pashtuns such as renaming the province were not backed by any serious increase in material resources. Growing inequality in the supply of electricity, water, jobs, health facilities and quality education meant the Taliban was able to present itself as a credible alternative to the dysfunctional Pakistani state. For example, in contrast to the official system of justice, the Taliban offer was quick and cheap. As the “war on terror” stoked anger, the military continued to fudge. The KPK government made a power-sharing agreement with the local Taliban in Swat in central Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa that, as Malala Yousafzai described in her BBC blog, the Taliban used to attack local girls’ schools.34 Under pressure from the US, the army invaded Swat in 2009, at a cost of thousands of lives and over 2 million refugees. Despite growing anger towards the US, Obama’s aid package of $7.5 billion over five years was accepted a few months later. This committed the military to support Obama’s so called “Af-Pak” strategy which used Pakistani troops to do the fighting against the Taliban and Al Qaeda with NGOs running development projects. Unable to create a sustainable opposition force to counter the Taliban, the package has failed miserably.

Pakistan today

Five years on, nothing of importance has changed. Military occupation has expanded, most recently in June 2014 with Operation Zarb-e-Azb in North Waziristan. The massacre of 143 children and staff in the Peshawar army public school in December 2014 was immediately followed by indiscriminate aerial bombing of tribal areas killing hundreds, all “terrorists” according to the military’s communiqués. The Pakistan media has dutifully repeated this despite being banned from the areas under attack. With 7,000 prisoners on death row, a six year old moratorium on implementing the death penalty was lifted. An emergency amendment to the constitution enabled military courts to handle terrorism cases, breaching the constitutional principle separating judiciary and executive.

“Modernisers” such as Imran Khan, leader of the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf, Movement for Justice Party (PTI), argue for integrating Pakistan further into the global economy. Representing the interests of the growing professional classes, they aim to create the growth that can ease national tensions and reduce the need for a strong state. However, the desire to demonstrate national unity at the top resulted in Khan calling off the four-month mass sit-in in the autumn of 2014 against vote-rigging and corruption, in order to unite with Muslim League, People’s Party and other parties to back the new counter-terrorism National Action Plan (NAP). After countless meetings of NAP committees, many chaired by the prime minister, actions such as shutting down the dozens of outfits on the official list of terrorist organisations have not been carried out. The Supreme Court found it necessary to order the government to publish the list. Having invested so much in its proxies, the deep state refuses to abandon them. Jamaat-ud-Dawa, political-welfare wing of Lashkar-e-Taiba, the terrorist organisation focused primarily on Kashmir, was able to bring over 10,000 supporters onto the streets of Karachi in protest against Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons.

Imran Khan’s calls for reform continue. Launched at a giant rally in Lahore on Independence Day, August 2014, his populist strategy gave hope to many. His supporters, together with those of the moderate cleric Muhammad Tahir-ul-Qadri, marched on Islamabad to sit down in front of parliament. The protest expressed the anger of all but the very rich at Nawaz’s failure to deal with the Taliban or to tackle any of the basic problems such as load-shedding and corruption. In June 2014 the fruitless efforts to find a “good Taliban” through talks with elements of the banned Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan ended after the humiliating attack on Karachi airport and the start of Operation Zarb-e-Azb.

The May 2013 election had been heralded as a step forward for Pakistan, as the Muslim League took over from the People’s Party, the first time a civilian government completed a full five-year term to be replaced by another. The new government put the former dictator Musharraf on trial. Such moves strengthened the US narrative of “fighting the Taliban in the name of democracy”, important given their plans to withdraw from Afghanistan having failed to defeat the Taliban. In reality, the pro “war on terror” governing parties in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, the Pashtun nationalist Awami National Party (ANP) and People’s Party were massively voted down. The Islamic reformists Jamaat-e-Islami (JI) and Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam (JUI) having equivocated on the “war on terror” also did badly. These defeats came as no surprise. At a cost of $100 billion since 9/11,35 the “war on terror” has broken tribal self-governing traditions and created widespread despair.

The election itself triggered unprecedented protests against vote-rigging. Despite the heavy military presence, Balochistan saw the independence movement’s mass support ensure a near complete boycott. In Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, pledging to end drone attacks, Imran Khan’s PTI topped the polls. In Punjab, Pakistan’s most powerful province, it was a “No” vote against the ruling People’s Party which gave victory to the PML-N, largely because the PTI could rally opposition to electricity shortages. Karachi and other cities in Sindh saw a huge vote against the gangster tactics of the Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM), Karachi’s ruling party for the last 25 years. The MQM is the party of the mohajirs, the relatively well educated and more affluent migrants from India who dominated Pakistan’s capital until it was moved from Karachi to Islamabad in 1959. The nationalisations of the 1970s saw young mohajirs marginalised as jobs went increasingly to new waves of migrants, mostly from rural areas. Initially a mohajir student leader, Altaf Hussain established the MQM as a reactionary force challenging this marginalisation and seeking concessions at the expense of others by trying to define the new migrants as privileged.

The ruling parties

The Muslim League had promised to revive the economy through deregulation and by cutting bureaucracy. It also pledged to increase spending on health, education, young people and women. Its industrialist backers, hampered by load-shedding and high interest rates, were to get privatisation, cheaper credit and international partnerships. On each point the government has failed. As its predecessor had done, the so-called circular debt owed to the electric power companies totalling Rs500 billion ($5 billion) was cleared by government. Nothing, though, was done to prevent big business dodging its electricity bills. Nor did the government have the confidence to end subsidies and raise prices to cover costs. After just 18 months the circular debt was back, the power companies were again unable to pay for their fuel and the load-shedding returned. The new government claimed that higher indirect taxes on mobile phone calls and petrol would pay the private power producers. This was simply to make workers pay while protecting capital. Other neoliberal policies such as lower interest rates, higher prices for basic goods, devaluation and an IMF bailout followed a pattern that has polarised Turkey, Egypt and Brazil. While the recent fall in oil prices will ease matters, the government’s failures, especially load-shedding, have undermined support in all but the best-connected business circles.

There is no shortage of ambitious objectives. Overall the plan is to increase growth to 5 percent a year and cut the deficit. In 2012 half of government spending went to the gas and electricity companies, vastly increasing the deficit. The current plan involves public sector spending cuts and privatising steel, airline and rail companies at a cost of hundreds of thousands of jobs. The funds released will further enrich the energy companies that already dominate the stock market. The other major beneficiaries are the textile, rice and leather exporters who get preferential treatment in tax reductions and rebates on exports. So the stock market rises not because the economy is booming but because of the super-profits of the energy and export sectors based on government support and subsidy. There is no reason to suppose that government commitments to the IMF to levy new taxes to lower the deficit will be any more successful than in the past.36

The government aims to restore investor confidence. What public investment takes place is built without any serious planning, only projects guaranteeing massive profits to the few. For example, the heavily subsidised Lahore Bus Rapid Transport, a single 16-mile route with 86 buses, has cost Rs30 billion (£200 million). Meanwhile Karachi, twice the size of Lahore, remains the largest city in the world without a publicly funded transport system, dependent on 10,000 privately owned buses and 50,000 six seater motor tricycles.

The middle class reformist challenge

Notwithstanding the apparent return of stable parliamentary government, hatred of the ruling elite continues. While rising inequality is global, Pakistan’s appallingly low spending on health, education and welfare as shown in its UN Human Development Index rating, remains much weaker than its GDP per capita would indicate. Public health spending is 1.0 percent of GDP in Pakistan, 7.8 percent in Britain and 8.3 percent in the US.37 Perhaps the harshest indicators are the statistics for the condition of women: In 2012 there were approximately 500 “honour” killings and out of a total of 9 million pregnancies, 4.2 million were unintended with 54 percent resulting in induced abortions, almost all clandestine. Some 623,000 women were treated for complications arising from induced abortions.38

In May 2013 the megacities Karachi and Lahore saw a massive uprising of young people protesting against the fixing of the general election. They were led by members of the professional middle class, challenging the ballot-rigging and demanding re-elections in almost 100 of the 290 seats contested. The success of the Balochistan independence movement’s election boycott ensured that its provincial government would be a puppet of Islamabad.

Almost all the political heavyweights from prominent KPK families suffered humiliating defeat at the hands of little known, middle class candidates, mostly from the PTI. Massive spending on roads and education in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, including scores of schools, 70 colleges and eight universities, failed to win votes as most people saw government sponsored developments as corrupt failures.

Imran Khan built his support thanks to his reform programme. People in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa voted for him hoping for an end to the war and a negotiated settlement with the Pakistani Taliban. The PTI is primarily a party representing professionals: doctors, engineers, architects, lawyers, managers in larger businesses. Together with educated youth keen to become professionals, they have emerged as a challenge to all middle class parties in the urban centres across Pakistan, asserting themselves ever more independently of big capital and its various political formations. Large numbers of lawyers and educated young people have been active against the war, corruption at highest levels and the interference of the military in civilian matters. The high points of this activity were the two “long marches” of the 2007 lawyers’ movement that twice resulted in the restoration of the senior judges sacked by General Musharraf. The urban youth now active in the PTI are led by students from middle class professional colleges particularly in Punjab and Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, desperate to rescue Pakistan from the disasters brought about by its Western-backed ruling elite.

Small and medium capital faced ruin during the years of People’s Party rule with its load-shedding, expanding war and the falling purchasing power of the mass of the population. Professionals, earning up to Rs7.5 million (£50,000) a year have not been weakened to the same extent. Traditional parties like the Muslim League and Jamaat-e-Islami who used to represent the small business class have failed to adapt. The PTI has emerged as representative of professionals, appealing to the masses by pointing to the poverty, rising inflation, corruption and lack of healthcare and education. Expressing the growing confidence of professional layers, it has benefitted from the weakening of the traditional petty bourgeoisie and its parties because of the impact of neoliberalism. The assertion of this layer against the super-rich, those associated with international capital and the domination of the military, comes from the realisation that they and those poorer than themselves pay most of the taxes while the rich and powerful are the main beneficiaries. Hence, despite the weakness of its policies—more private investment, less state involvement and a bigger role for NGOs—the PTI programme has a strong appeal when it says it will jail the corrupt, bring their money back to Pakistan and end their privileges and manipulation of the state machinery.

Pakistan needs approximately $40 billion to pay for its imports. Exports bring in $25 billion; remittances from Pakistanis working abroad, mainly the Middle East, Europe and USA contribute $14 billion, a six-fold increase in the past 12 years. Imran Khan and the cleric Tahir-ul-Qadri have appealed to Pakistani professionals living abroad, promising to give them a role in the country’s politics. This appeal to expats has provided almost 80 percent of PTI funding enabling it to spend billions on media campaigns. It is noticeable, though, that unlike the traditional parties that build local organisation, the PTI cadres find themselves mere cheerleaders as private event managers run the PTI rallies.

Western media have regularly used Imran Khan’s opposition to war and calls to negotiate peace with the Pakistani Taliban as evidence that he is right wing. In reality, the PTI is socially liberal and uses a mix of Islam and nationalism similar to that used by the People’s Party when it was founded in the late 1960s and earlier by the Muslim League itself. When it comes to negotiating with imperialism, the PTI has proved no less willing to compromise than the established parties. In late 2012, as the Muslim League’s attempt to create a movement against People’s Party rule was failing, it was the PTI that emerged as a challenger both to the Muslim League and the People’s Party. As a result, a number of Muslim League stalwarts joined the PTI. However, the floodgates did not open, largely because the PTI was too weakly organised, particularly in rural areas. In class terms, the PTI challenge to the Muslim League is a challenge by the professional layer to big and medium sized capital.

The 2013 elections in Pakistan showed the mix of revolts that have hit this so-called frontline state in the war against terror. Like any rebellion, it brought to the fore new political forces that challenge the system in apparently reformist ways. However, up till now those involved have very high expectations. In KPK, despite the wave of support for the government after the Peshawar massacre, there is a huge desire for an end to the war. In Punjab, it is the energy crisis that motivates mass opposition. In Karachi and Sindh’s other cities people want an end to the politics of the gun.

The election generated hopes that the indifference of the ruling elite would disappear and that poverty, unemployment and hunger would be addressed. The Karachi youth who came out in their thousands demanding the right to vote after the MQM had stopped them were among the 30 million on the electoral register targeted by billions of rupees of state and NGO money exhorting them to vote. Professional middle class leaders like Imran Khan promised a “tsunami” that would not only wipe out their opponents but the entire structure of state repression. Business class leaders like Nawaz Sharif roused hundreds of thousands at rallies claiming voting Muslim League would save Pakistan from those destroying it. It is the promise of such “revolutions” of the professional middle class and the business class leaders that instilled hopes of reform into millions everywhere except Balochistan. Now these parties have to put the genie back into the bottle.

The millions who voted PTI in May 2013 included many young people but also 80 percent of women voters in Karachi and other parts of urban Sindh. In Lahore hundreds of thousands of under-25s voted PTI in the hope it would wipe out the old, corrupt ruling system. However, the PTI leadership failed to take up this huge challenge. It limited the movement to social media and sit-ins under military protection rather than spreading the movement to workplaces, colleges and universities. Nor was it ready to give a strike call to demand fresh elections in the many seats its supporters consider lost due to vote-rigging. It wanted to reinstate faith in the failed Election Commission, persuading people to believe it is not the system but its mismanagement that is the problem. It was also eager to accept the results in KPK and form a government. Hence Imran Khan nominating billionaire Pervaiz Khattak as KPK chief minister.

These attempts to put a lid on the movement and impose leadership on the various assemblies that claim to represent the will of the people show a fearful ruling class. This widening gap between hopes and reality grew dramatically at the beginning of 2013 when Qadri mobilised people to march on Islamabad demanding electoral reform. The 20,000-strong Islamabad dharnas (sit-ins) that started in August 2014 led by Khan and Qadri, and with some support behind the scenes from the military, allowed a further demonstration of popular anger.

Why do such movements fail to break a system imposed from above and seen by all to be weak? The answer lies in the contending forces. In Karachi the PTI emerged as a force challenging the mafia-style rule of the MQM. Here a huge majority of the population voted against the MQM who, as usual, rigged the elections winning 18 out of 20 seats. The protests by young people, at first independently organised, were quickly taken under control by the PTI leadership wanting to pressure the Election Commission to permit some repolling. When the MQM terror struck one day before the repolling of only a part of one of the 19 disputed seats, a majority of would-be PTI voters were terrorised into staying at home. All parties opposing the MQM had demanded elections under military supervision. The state ensured that its military presence appeared as a neutral force stopping the MQM killers from attacking those voters who appeared on the repolling day. In the event, the turnout was down by three quarters. Those wishing to rid Karachi of the MQM stranglehold were reminded by the military that it is they who decide if the masses will be allowed to participate in the parliamentary process. It was the same when, in early 2014, tens of thousands, having taken part in a “long march” to the capital Islamabad, braved the cold and rain to sit-in for five days in front of the national assembly until Qadri, fearful of a police attack, retreated with a sham set of promises.

The “tsunami” mobilised by the PTI, the march and the sit-ins organised by Khan and Qadri all presented a Pakistani nationalist view based on fear of a collapse of the state, reflecting the growing chaos experienced by the professional and middle classes. They have attracted the support of a huge mass of the underprivileged by claiming they will rid the system of its corrupt rulers. They use the words “revolution” and “tsunami” but their attempt to halt the decline is an entirely reformist scheme. At its core is the desire to continue with this systematic indifference towards the working masses. When pressured by the military, Imran Khan will abandon his supporters, for example, calling off the 2013-14 blockade of NATO supplies to Afghanistan staged in protest against the US use of drones. The professional and middle classes have neither the strength nor the will really to challenge the system. They raise the hopes of the masses only to limit any movement that arises. They call for free and fair elections but only for a parliament full of billionaires and the already powerful. They challenge the mafia-style rule of the MQM but they wish only to take the place of the MQM. They call for an end to state terror in Balochistan but only in so far as such lip-service is needed to cover their Pakistani nationalism, a nationalism that has always denied any demand for freedom for the Baloch.

Since the 1970s industrialists in Sindh and Punjab have robbed Balochistan of its gas reserves. More recently this pillage has been joined by Australian and European multinationals. The new Gwadar port in Balochistan and the highways connecting it help Pakistani and Chinese capital but marginalise the local population. Such developments have changed Baloch resistance from its roots in partition and Balochistan’s subsequent occupation by the Pakistani military. What used to be fought and led by tribes and tribal leaders in the mountains is now taking place in the populated areas along the coast under middle class leadership, a vicious conflict characterised by “disappearances” and cold-blooded murders of political activists. Meanwhile the Pakistani state claims that minor interventions by Iran and Afghanistan are a threat to Baloch interests. However, it is with precisely these same “interventionists” that the Pakistani state is working on mega-projects including the Iran-Pakistan gas pipeline and Afghan-Pakistan hydropower projects.

“Laissez-faire” urbanisation and ethnic division

The toughest of all the “ethnic” political parties remains the MQM. However, as the IMF-led privatisations of the 1990s brought professional education and jobs back to Karachi, the MQM turned itself into a Karachi nationalist formation. It broadened its base, substituting “Muttahida” (United) for “Mohajir” in its name and championing the development of Karachi. Based among the lower middle classes, its leadership used gangster muscle power to silence its opponents, thousands of whom have been killed since the late 1980s.

Despite this, challenges to the MQM’s rule have grown as Karachi has become divided into areas held by competing mafias. Mass migrations from rural areas, especially from Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa and Sindh, have brought major changes in the city’s political landscape. Today Karachi stands divided into three distinct parts each ruled by a mafia with its own political cover. The resulting weakening of MQM control has led big capital to call for power sharing between the MQM, the People’s Party and Pashtun nationalists. The recent elections saw the PTI emerge as the second largest party in Karachi. Had the MQM not rigged the vote, the PTI would have taken at least half Karachi’s seats.

In Karachi the huge, if often passive, support for the PTI has put MQM leaders under tremendous pressure. Its weakness is also a problem for the Pakistani state; demanding rights for mohajirs, the MQM’s core support, has allowed big business and state institutions to use divide and rule to crush resistance. However, the havoc of privatisation and deregulation has unleashed a new generation of tens of thousands of the unemployed and semi-employed that the MQM alone cannot manage. Threatened by Karachi’s instability, big business has been suggesting multi-party rule for some years. The PTI leadership sees the protests as an opportunity to show it has a serious popular base. However, it also has to show it has the power to coerce the masses it has mobilised, to suppress workers and students from organising where they work and study. This combination of consent and coercion, which the MQM has sustained for 25 years, no longer works, creating the possibility for alternatives. The military’s choice has been to give the Pashtun middle classes in Karachi proper representation. In 2015 the paramilitary Sindh Rangers carried out a massive campaign against the street power of the MQM and, to a lesser extent, the PPP. With around 500 extra-judicial killings—many “shot while trying to escape”—they have forced the remaining MQM militants underground. For the first time in decades an MQM call in September for a city shutdown, in protest at extra-judicial killings, failed.

Where now?

If reformist leaders succeed in restricting the movement to changes through parliament, its aims will remain limited to power struggles between members of the elite. Against this possibility the resistance from below constantly asserts itself. There are daily protests against water shortages and load-shedding. Larger-scale protest movements have successfully blocked the building of new dams. The post-election budget triggered strikes in state enterprises and government offices, winning 10 percent pay rises. The 20,000 members of the Faisalabad-based power loom workers’ union, the Labour Qaumi Movement, have achieved the distinction of being accused of bullying by local employers forced to pay wage increases. The fisherfolk organisation, Pakistan Fisherfolk Forum, mounted mass protests successfully challenging the theft of inland fishing rights by the paramilitary Rangers. The Young Doctors Association in Lahore struck successfully, forcing chief minister Shahbaz Sharif to negotiate with them over both their pay and conditions and the provision of free healthcare. In Gilgit-Baltistan, Shia and Sunni united in a week long mass “shutter down” and “wheel lock” strike in April 2014 to force the federal government to restore the bread subsidy. In Punjab the brick kiln workers’ movement against debt bondage has mobilised thousands against the kiln owners.

While none of these movements is national in scope, the demand for democracy that has drawn people into activity since the 2013 election means greater opposition to neoliberalism. The elite are ever more divided on the “war on terror”. They are also split on whether to promote a bigger role for international capital, so further limiting democracy and weakening trust in state institutions while requiring more military operations. The alternative is to rebuild trust in the state and check the role of global capital. As a result, the ruling elite has been forced to deliver reforms and restore the independence of the judiciary, resulting, if only temporarily, in huge numbers of anti-corruption cases. However, none of these movements has spread far enough to include the national question, the Baloch and the Pashtun insurgencies, nor has the working class managed to put itself at the centre of these struggles.

Large numbers of young people, especially students in Punjab and in other urban centres are now engaged in PTI politics. The PTI leadership wishes to keep all struggles confined to winning seats in elections. Time and again it has lagged behind its supporters. Despite this the prospect of new, larger protests will not disappear. An important example is the all-out strike against the privatisation of Pakistan International Airlines which saw hundreds of thousands take solidarity action across Pakistan after the military killed two PIA workers on a demonstration at Karachi airport.39 It is up to those wishing to overthrow this rotten system to organise where they work, where they study and on the streets to unite the movements of resistance against war and neoliberalism.

Notes

1 Marx, 1976, p799.

2 Ahmed, 1983.

3 Callinicos, 2009, p12.

4 Alavi, 1981, Ashman, 1997, Luxemburg, 1963, p371, Marx, 1853.

5 “From 1802 to 1814, the East India Company built 31 ships in London and 38 in India”—Prothero, 1979, p49.

6 Belokrenitsky, 1991.

7 Alavi, 2002.

8 Abbas and Foreman-Peck, 2007.

9 Ahmed and Amjad, 1984.

10 For example Papanek, 1967.

11 Zaidi, 2015, p6.

12 Shaheed, 1983.

13 Shahid-ur-Rahman, no date.

14 Weiss, 1991, pp34-35.

15 Alexander and Bassiouny, 2014, p43.

16 Asdar Ali, 2005, p88.

17 Harman, 1994.

18 Harris, 1986.

19 Dawn, 2014.

20 Subohi, 2015.

21 World Food Programme, 2012.

22 Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, 2013, figures for manufacturing as a whole.

23 Jamal, 2014.

24 Hasan and Raza, 2015.

25 Dawn, 2015.

26 Alavi, 1983.

27 Jinnah, 1940.

28 For one example of the elite’s hypocrisy, see Armytage, 2015: “Blurred lines: Business and Partying among Pakistan’s Elite”.

29 Fell McDermott and others, 2014.

30 North West Frontier Province till 2010.

31 See Brown, 2015.

32 Go to http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SE.XPD.TOTL.GD.ZS

33 Guardian Global Development Data, 2011.

34 Yousafzai, 2009.

35 Dawn, 2013.

36 Iqbal and Kiani, 2015.

37 World bank figures: data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.PUBL.ZS

38 World Economic Forum, 2014; Junaidi, 2015.

39 Ahmed, 2016.

References