Capitalism and war have always been profoundly connected. Max Weber noted the important role that financing the wars of European states played in the development of early modern capitalism.1 The bond remains as tight as ever today. As the illusions of neoliberal globalisation have dispersed, we find ourselves in a new epoch of inter-imperialist competition. The proxy war waged by NATO against Russia in Ukraine is simply the first round in the developing conflict between the declining hegemon, the United States, and its most serious challenger, China.2 Donald Trump’s denunciations of the “forever wars” waged by his predecessors have not stopped Congressional committees drafting proposals for a $1 trillion (£741 billion) defence budget for the 2026 financial year.3 It is not surprising therefore that we are seeing a revival of interest in the work of Michael Kidron (1930-2003), the most important Marxist theorist of the Cold War Permanent Arms Economy (PAE).4

Marxism and the economics of war

The first epoch of inter-imperialist wars between 1914 and 1945 had Marxists of the calibre of Rosa Luxemburg, Nikolai Bukharin and Henryk Grossman seeking to decipher the relationship between militarism and capital accumulation. But it was the development during the Cold War of high levels of peacetime arms spending that provoked the most serious theoretical exploration of the connection. “Peacetime” here refers to the absence of general wars between the Great Powers during the Cold War, as its name implies.5 This made it very different from the preceding era of world wars between 1914 and 1945. There were, of course, major wars waged in the global south, which rapidly became the arena where the Cold War turned hot—above all in Korea, Indochina, the Middle East and Afghanistan.6

In an important recent study of US military Keynesianism during the Cold War, Tim Barker highlights the distinctiveness of “Cold War capitalism—especially of the high military Keynesian period of 1950-1970, when the defence share [of US gross domestic product] never fell below 9 percent—…a qualitatively more militarised economy” than the US in the 21st century, when defence spending normally does not exceed 5 percent of national income.7 The emergence of this PAE coincided with the trentes glorieuses, the “thirty glorious years” of the long postwar boom of Western capitalism (in fact, slightly less than 30 years, since it spanned the period 1948-73). As Kidron put it towards the end of this era, “High employment, fast economic growth and stability are now considered normal in western capitalism”.8

Initially, this outcome came as a surprise. As Barker documents, commentators of different political persuasions warned that the end of the Second World War would lead to the kind of economic crises that had followed the First World War, threatening the replacement of capitalism with socialism. The Cold War strategy of Harry S Truman’s administration, set out in the famous NSC-68 memorandum of April 1950—drafted by Wall Street banker Paul Nitze and implemented after the outbreak of the Korean War three months later—demanded a huge surge in defence spending and ensured there would be no return to the 1930s.9 As Nitze put in 1953, “Korea came along and saved us” from the political resistance from sections of the ruling class to higher arms spending.10

But how to conceptualise the relationship between capital accumulation and military expenditure? It is regrettable that, despite offering a sophisticated and enlightening analysis of the shifting and sometimes conflicting interests of different fractions of US capital in the PAE, Barker never goes beyond a conventional post-Keynesian explanation of the macroeconomic effects of high defence budgets in stimulating effective demand and hence employment, investment and consumption.11 Even Tony Cliff, the Palestinian Marxist who was Kidron’s closest political collaborator when he developed his theory of the PAE, remained within a broadly similar intellectual framework. In his own pioneering 1957 essay, “Perspectives for the Permanent War Economy”, Cliff uses the Keynesian conception of the multiplier to explain the impact of arms spending in increasing national income.12

Whatever the merits of these analyses, they fail to situate the PAE within Marx’s theory of capital accumulation and crises. Cliff’s own most important theoretical contribution, his analysis of the Soviet Union as neither socialist nor (as Trotsky had argued) a degenerated workers’ state, but bureaucratic state capitalism, nevertheless finds an important place for military production. In the first place, it is the pressure of geopolitical competition with Western imperialism that imposes the logic of capital accumulation on the Stalinist bureaucracy by compelling it to give priority to investment in the heavy industries required to supply the military. Secondly, Cliff has a brief discussion of the relationship between the tendency towards economic crises inherent in the capitalist mode of production and the specific characteristics of state capitalism. Here he notes the feature of what he calls “war production” that plays such an important role in Kidron’s analysis of the PAE, namely that it is a form of unproductive consumption “which, while it is a subtraction from the process of reproduction just as much as the personal consumption of the bourgeoisie, nevertheless constitutes a means in the hands of the bourgeoisie to get new capital, new possibilities of accumulation”.13 But the discussion is inconclusive. Cliff was writing in 1947-8, in the very early stage of the Cold War, before the Soviet Union had acquired nuclear weapons and therefore before the peculiar logic of a global geopolitical conflict regulated by the inevitability of “mutual assured destruction” if a general war broke out had been properly delineated.

Decoding the Cold War

It is here that Mike Kidron made a decisive contribution by situating the fully developed PAE with respect to the main mechanism that, according to Karl Marx, drives capitalism in a cycle of boom and slump, the law of the tendential fall in the rate of profit presented in Capital, Volume III, Part 3. First, a word on Kidron himself and on the context in which he developed his theory.14 He was born in Cape Town in 1930 to an affluent Zionist family who emigrated during the 1940s to what was still the highly contested British colony of Palestine but much of which was seized by the new State of Israel in the Nakba of 1947-9. Kidron moved to Britain in 1953 to study for a DPhil at Balliol College Oxford. He soon was persuaded by Cliff to join the Socialist Review group, the tiny Trotskyist organisation that he and his wife (and Mike’s sister) Chanie Rosenberg were seeking to build in Britain in the very unpropitious conditions of the Cold War at its height and an unprecedented economic boom. The group’s defiant slogan, rejecting both the global antagonists, was “Neither Washington nor Moscow, but International Socialism!”.

Kidron quickly became one of the group’s leading activists and the editor of Socialist Review. Roger Cox, a young worker who joined in the late 1950s, recalls “Mike Kidron and Reuben [later Robin] Fior, who were incredibly charming and were really funny. The most important thing about them was that they listened. You talked about life at work, and they listened”.15 Kidron’s intellectual gifts ensured he became the first editor of the theoretical journal the Socialist Review group helped to found in 1960, International Socialism (the group subsequently became known as the International Socialists). Among his close collaborators was the philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre, who co-edited International Socialism in 1961-2. Recalling his long career at the age of 80, MacIntyre, by then a Catholic follower of St Thomas Aquinas, wrote in his characteristically contrarian way:

The two standpoints without which I would have been unable to understand either modern morality or twentieth-century moral philosophy are those of Thomism and of Marxism, and I therefore owe a large and unpayable debt of gratitude to those who sustained and enriched those marginal movements of thought in the inhospitable intellectual climate of capitalist modernity, including Thomists as various as Maritain, Garrigou-Lagrange, De Koninck, and McInerny, and Marxists as various as Lukács, Goldmann, James, and Kidron.16

It was in its pages of this journal that Kidron made his most important contribution to Marxism, notably “A Permanent Arms Economy” (1967), which represents in embryo the fuller analysis in Western Capitalism since the War (1968, 1970). Kidron was by no means focusing exclusively on the PAE. His effort was to grasp the specific dynamics of postwar capitalism, which he argued differed in important respects from the imperialism portrayed by Lenin, Trotsky and other revolutionary Marxists in the early 20th century. Such a reappraisal, Kidron believed, could help to rearm a revolutionary left that was facing new openings thanks to the crisis of Stalinism unleashed by Nikita Khrushchev’s 1956 secret speech denouncing Stalin’s dictatorship and the Hungarian Revolution it helped to provoke, by the escalation of anticolonial struggles, and by the emergence of a powerful mass movement against nuclear weapons in Britain.

Kidron brought to this task a deep empirical engagement with the functioning of postwar capitalism, a powerful grasp of the concepts of the Marxist critique of political economy and a readiness to sacrifice the sacred cows of left orthodoxy. These qualities were very much in evidence in an article published in 1962, five years before “A Permanent Arms Economy”, entitled “Imperialism—Highest Stage but One”. Here he shows the limitations of Lenin’s classic analysis, partly because he overgeneralises from the case of German “finance capital” but mainly because of “the change in the locus and forms of accumulation”, as capital investment became primarily self-financing and concentrated in the advanced Western economies themselves, therefore making the loss of empire more palatable to colonial powers such as Britain and France.17

Kidron undoubtedly knew what he was talking about. As a professional development economist, he closely studied the changing patterns of involvement of foreign capital in India, once the financial and military lynchpin of the British Empire, as a result of independence and the associated rise of the Indian bourgeoisie.18 He was a brilliant communicator, making his points in lucid, punchy, economical prose, and (as I can bear personal witness) entrancing audiences with his eloquence, wit and flair for metaphors. But his distaste for the dogmatism of much of the Marxist left sometimes led him to make his points in misleadingly absolute terms. To dismiss imperialism as a passing phase of capitalist history at a time when gigantic, bloody national liberation struggles—above all those in Algeria, Vietnam, Portugal’s African colonies and Palestine—were helping to draw a new generation into revolutionary politics worldwide was a serious misjudgement that contrasts with Kidron’s own practical solidarity with the Algerian cause in particular.19

It should be emphasised that Kidron had to grapple with two mistaken approaches to postwar capitalism. One was the dogmatism of much of the Stalinist and Trotskyist left that held that essentially nothing had changed in postwar capitalism and tended to ignore or explain away the boom of the 1950s and 1960s. Kidron made a particular brutal example of the Fourth International leader Ernest Mandel, at his best a gifted Marxist economist.20 But the other, and much more powerful, ideological tendency was that of the Western mainstream, which argued that, thanks to the techniques of Keynesian demand management, capitalism had overcome its economic contradictions and could avoid the old oscillation of boom and slump. In Britain, this argument was made particularly powerfully by two leading theorists of right-wing social democracy, Anthony Crosland and John Strachey, himself an ex-Marxist.21

In a brilliant earlier demolition of Strachey’s The End of Empire, Kidron anticipates “Highest Stage but One”, affirming: “We have to concede that imperialism as defined by Lenin is on the way out, barbarically at times, but nonetheless on the way out.” He also sets out his own programme: “It is time for the Left to cease being the mastadons of revolution and for it to come to grips with contemporary capitalism and its mode of survival”.22 Kidron, in other words, was combating two kinds of apologetic tendency—one that insisted nothing had changed, the other that claimed that postwar capitalism had changed beyond recognition.

His words, published in 1961, have lost none of their actuality in the succeeding decades: “whatever the future holds, it is one of irreparable instability, of crises whose violence is such as to question the continued existence of capitalism as a world system at best, or at worst of civilization itself”.23 This passage comes from an article where Kidron first sets his theory of the PAE, though later texts develop the theoretical underpinnings more systematically. In both this article and the slightly earlier critique of Strachey, he emphasises the chronic problem of surplus capital that capitalism perpetually struggles with—in other words, the accumulation process generates more capital that can be profitably invested. Imperialism and the PAE can both be understood as temporary solutions to this problem: “Where imperialism righted capitalism’s bias to over-production productively, therefore imperfectly and temporarily, the arms economy looks to doing so destructively. therefore perfectly (but, for reasons I cannot adduce here, not permanently)”.24

As I have already noted, Kidron’s mature theory of the PAE centres on the law of the tendential fall in the rate of profit. He insists: “If you reject the thesis of the declining rate of profit, then you reject the entire Marxist analysis”.25 For Marx, competition compels individual capitals to invest in improved methods of production that lower their costs relative to those of their rivals. But this causes the organic composition of capital to rise. In other words, higher labour productivity is expressed in rising investment in the means of production compared to that in the employment of labour-power. But it is labour that creates new value, and more particularly the surplus-value that is the source of profits. In Capital, Volume I, Marx focuses on the rate of surplus-value, which compares surplus-value to the wages paid to workers to create it. But for capitalists the crucial variable is the rate of profit, which compares surplus-value to the total capital they advance, that is their investment in the means of production as well as in labour-power. The rising organic composition of capital causes a fall in the rate of profit even if the rate of surplus value remains constant and potentially even if it rises.

As Kidron notes, Marx emphasises the existence of “counteracting factors”: “He iffed and butted the ‘law’ extensively and was at pains to explain that ‘this fall [in the rate of profit] does not manifest itself in an absolute form, but rather a tendency towards a progressive fall,’ but he clearly considered it the overriding trend”.26 In fact, the most important of these counteracting factors (though not listed as such by Marx) is the devaluation and destruction of capital that takes place during economic slumps. This is made clear in what is in many ways the most important part of Marx’s discussion of his law, in the chapter carved out by Engels from his manuscript and entitled “Development of the Internal Contradictions of the Law”. Here Marx understands the tendency for the rate of profit to fall as the specific form taken in the capitalist mode of production of the development of contradictions between the forces and relations of production. It is rising productivity that leads to the fall in the rate of profit:

The tremendous productive power, in proportion to the population, which is developed within the capitalist mode of production, and—even if not to the same degree—the growth in capital values (not only in their material substratum), these growing much more quickly than the population, contracts the basis on behalf of which this immense productive power operates, since this basis becomes ever narrower in relation to the growth of wealth; and it also contradicts the conditions of valorization of this swelling capital. Hence crises.27

Capital—above all in the form of constant capital—grows too large to be profitably employed, tipping the economy into recession. “All this therefore leads to violent and acute crises, sudden forcible devaluations, an actual stagnation and disruption in the reproduction process, and hence to an actual decline in reproduction.” But crises also create the conditions under which investment becomes profitable again. Firms go bust, so their assets can be bought up cheaply by surviving capitalists; mass unemployment forces workers to accept lower wages and speed-up. The mass of capital shrinks and the rate of surplus-value increases. Rising profitability eventually allows a resumption of growth. “And so we go round the whole circle [Zirkel] once again. One part of the capital that was devalued by the cessation of its function now regains its old value. And apart from that, with expanded conditions of production, a wider market and increased productivity, the vicious circle [fehlerhafte Kreislauf] is pursued once more”.28

In his first account of the PAE, Kidron emphasises how the destruction of capital is actually functional to the accumulation process:

For Marxists, the problem presented by the absence of major slumps these last twenty years boils down to an enquiry into the factors that have fractured the compulsive accumulation-overproduction sequence. Logically, the factors fall into two groups: capitalism can either expand its markets or else destroy, partially or wholly, its constantly accumulating productive capacity.29

Kidron dismisses the first factor, which he associates with reformist versions of Keynesianism: the rising wages these explanations rely on will eventually eat into the rate of profit. “This brings us to the second type of solution open to capitalism—the destruction or partial destruction of capital. Even in its most progressive phase, capitalism has resorted to destruction in order to sustain itself. Slumps were ruinous of capital; wars even more so”.30

It is here that the specific properties of arms production become significant. In Capital, Volume II, Marx analyses the capitalist process of reproduction via the circulation of commodities and capital. This process depends on two main departments of production: I, which produces means of production, and II, which mainly produces the means of consumption of the working class. Though Marx does not put it exactly like this, both these departments represent forms of what he calls “productive consumption”, since their products feed back into the process of production, by supplying workers with the means to make new commodities and to reproduce themselves and their families. But he notes in passing the existence of the subdivision Department II(b), which, unlike II(a), producing the means of consumption for the working class, is responsible for “luxury means of consumption, which enter into the consumption only of the capitalist class, ie can be exchanged only for the expenditure of surplus value, which does not accrue to the workers”.31

As we have seen above, Cliff had already noted the significance of this sector for understanding the economics of militarism. Kidron seizes on arms production as a form of unproductive consumption that counteracts Marx’s law of falling profitability. He emphasises the sheer scale of Cold War military spending:

The addition made by arms budgets to world spending is stupendous. In 1962, well before Vietnam jerked up American (and Russian) military outlays, a United Nations study concluded that something like $120 billion (£43,000 million) was being spent annually on military account. This was equivalent to between 8 and 9 percent of the world’s output of all goods and services, and to at least two-thirds, or even as much as, the entire national income of all backward countries. It was very near the value of the world’s annual exports of all commodities. Even more breathtaking is the comparison with investments: arms expenditure corresponded to about one-half of gross capital formation throughout the world.32

This last comparison is crucial in representing the scale of military spending compared to the process of capital accumulation. The effect was to draw off a vast amount of value most of which—in conditions of competitive accumulation—would have otherwise been productively invested in departments I and II(a). This investment, had it taken place, would have led to the rapid increase in the organic composition of capital and therefore a fall in the rate of profit—a return to the prewar “vicious circle” of boom and slump. High levels of arms expenditure slowed down the rate of accumulation, and thereby permitted slower, but more stable and consistent growth than would have occurred if the rising organic composition of capital and the falling rate of profit had been allowed to develop unabated (it is this, presumably, that Kidron has in mind when he refers to the “partial destruction of capital” in the passage cited above). As he succinctly puts it in response to a critic, David Yaffe,

Military expenditure affects both the rate and the mass of profit. It sustains the rate by preventing or slowing down the rise in the organic composition of capital in the productive sector—that is its “depletion effect”, the sterilisation of vast quantities of plant and machinery by tying them to military procurement. At the same time military expenditure cuts into the mass of profit available to the productive sector—it has a “taxation effect”. It can keep the rate up only by keeping the mass down, and vice versa.33

But even if the PAE temporarily limited the operation of the mechanisms that, for Marx, are the main drivers of crisis, it too arises from the same remorseless logic of competitive accumulation. Kidron takes some trouble to deal with the social-democratic argument that what Maynard Keynes calls the “somewhat comprehensive socialisation of investment”, which he claims is “the only means of securing an approximation to full employment”, could have performed the same stabilising role as arms production.34 Barker argues that, in the postwar US, “the major advantage of military Keynesianism was that it did not threaten capitalist control over the ‘decisive functions’,” above all, investment, “but it did achieve a version of what Keynes had in mind … US defence spending from 1947 through 1991 averaged 10.5 percent of net national product, with a range 7 to 17.5 percent—nearly exactly matching Keynes’ quantitative sense of what the socialization of investment might encompass”.35

Kidron’s perspective on the role played by the PAE roots it more directly in the logic of capital:

Internationally, the system still performs in the classic manner through constant mutual adjustment by national capitals … any country opting for full employment and stability through productive investments or even unproductive “hole-filling” public works is bound to suffer in world competition. Full employment might be achieved, but it might be achieved in isolation; and the result would almost certainly be a degree of inflation that would prise the single economy out of world markets. For it to endure, the ability of others to undermine it must be contained. In other words, full employment must be exported, and what better compulsion to “buy” it than an external military threat?

… One can admit that the initial plunge into a permanent arms economy was random—without affecting the issue. The important point is that the very existence of national military machines of the current size, however happened upon, both increases the chance of economic stability and compels other nation states to adopt a definite type of response and behaviour,which requires no policing by some overall authority. The sum of these responses constitutes a system whose elements are both interdependent and independent of each other, held together by mutual compulsion—in short, a traditional capitalist system.36

The stabilising effect of the PAE was, however, only temporary. The uncontrolled arms race at the height of the Cold War was both existentially threatening and economically costly, creating powerful pressures to limit military expenditure:

The existence of an economic limit on arms outlay is crucial to the permanent arms economy. In a war economy the limits are set by physical resources and the willingness of the population to endure slaughter and deprivation. In an arms economy, the capacity of the economy to compete overall, in destructive potential as well as in more traditional forms, adds a further constraint.37

The pressure to economise on the military reinforces a tendency for arms production to become more technologically specialised and capital-intensive, thereby reducing the spin-offs it had previously provided to civilian production, and giving rise to

the intractable form unemployment takes in a permanent arms economy. Rapid unplanned—and unplannable—technological change in the arms industries within a ceiling on expenditure creates regional-industrial husks of unemployment that remain grossly insensitive to general fiscal and monetary cures, and unskilled strata unemployable by the high-flying, quick changing technologies in use. Again, high boom in the west is obscuring the point, but the plight of the shipbuilding areas here and in the United States, the problems of the aircraft manufacturing areas in the US, even the problems of the American blacks owe at least something of their intensity to the changing tides of military expenditure and the increasing complexity of production for military use.38

This analysis overlaps interestingly with perhaps the high-point of Barker’s study of US “military Keynesianism”—his account of the Vietnam war boom, which was unfolding as Kidron developed his theory of the PAE. This was a boom centred on hi-tech industries that fed a military campaign conducted primarily, like so many wars waged by Anglo-American imperialism, with bombs and missiles. It pulled up inflation, starting in capital goods, then spreading to the rest of the economy, but it also left more consumer-oriented industries, such as housing and autos, depressed. This combustible mixture produced an upsurge in wage militancy interacting with the inner-city risings, the most powerful of which—Detroit July 1967—took place in Motown, where Black unemployment had risen from 3 to 8 percent in the preceding two years.39

A neglected aspect of Kidron’s own analysis is his preoccupation with understanding the PAE’s impact on workers—high employment and the increasing economic dominance of big industrial corporations empowering some through the development of plant-level decentralised pay bargaining, but excluding others, most notably blacks in the US.40 This reflected the broader political preoccupation of the Socialist Review group/IS (noted by Roger Cox in his memories of the 1950s and 1960s) with the actualities of working-class struggle during the Long Boom.

The legacy

The late 1960s marked a turning point. Defence spending began to fall as a share of US GDP, and—despite a surge under Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan at the height of the “Second Cold War” in 1979-85—never again recovered the heights reached in the 1950s and 1960s.41 The presidency of Richard Nixon (1969-74) sought withdrawal from Indochina, détente and arms control agreements with the Soviet Union, and a reversal of the declining competitiveness of US civilian industries compared to the revived capitalisms of West Germany and Japan. The “Nixon Shock” of August 1971—when the administration took the dollar off gold and imposed a 10 percent import surcharge—was an attempt to achieve this last objective. The result was a short-lived but intense economic boom that stoked global inflation and ended in the first great postwar recession in 1973-5. It was followed by an even more severe slump after Federal Reserve chair Paul Volcker sharply increased interest rates in October 1979, successfully breaking the inflationary spiral and disciplining labour. This “Volcker Shock” marked the global advent of neoliberalism.42

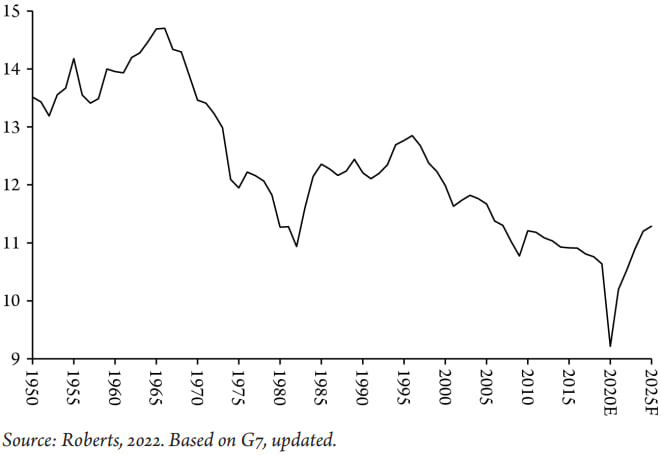

Kidron’s prediction that the PAE was becoming an increasing source of instability helps us to understand this return of crises. As investment shifted from the arms sector to civilian industries, the classic tendencies analysed by Marx for the organic composition of capital to rise and the rate of profit to fall reasserted themselves. Indeed, numerous Marxist studies demonstrate that it is precisely in the late 1960s that capitalism entered the crisis of profitability that neoliberal efforts to force up the rate of exploitation have only partially overcome (see Figure 1).43 Michael Roberts, a leading Marxist researcher into the law of profitability, to whom I am indebted for the graph below (and for many other things), has recently cited the decline in arms expenditure relative to GDP during the final phase of the long boom in the 1960s as evidence against the PAE theory.44 But Kidron never claimed that arms were the sole force driving the boom—other factors were involved, for example, wartime destruction of capital and postwar expansion of the urban workforce with the entry of married women, migrants and peasants. Roberts, moreover, overeggs the cake by exaggerating the health of Western capitalism during the 1960s—a period when instability was increasingly marked, not just by workers’ strikes and urban revolts, but by the currency crises that afflicted first the pound sterling and then the dollar, symptoms of both British and US relative decline and of the growing internationalisation of capital.

Figure 1: The fall in the rate of profit since 1950 (percentage)

Kidron himself became sceptical about his own theory. By the late 1960s, he was increasingly disaffected with the turn that IS made, as it recruited students and workers radicalised by the tumults of the time, towards Leninist forms of organisation, a process that culminated in its transformation into the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) in 1977. In an article I commissioned as editor of International Socialism for its 100th issue that year, Kidron cast doubt on the ability of the PAE and more broadly traditional Marxist political economy to understand a world that was becoming dominated by nationally integrated state-capitals.45 This was another bad misjudgement, given the drive towards the internationalisation of capital and the subjection of both firms and states to market disciplines that neoliberalism would unleash. Kidron’s younger co-thinker Chris Harman provided a cogent reply to Kidron at the time and would later go on to build on his work, particularly in two books that integrated the PAE theory into a much larger canvass of the history of capitalism.46

Nevertheless, even here there was a kernel of truth in Kidron’s argument. He constantly stressed the effects of the concentration and centralisation of capital that the PAE helped to reinforce: “As capitalism ages its constituent capitals get fewer and larger, more dangerous and more vulnerable to one another and more dangerous and vulnerable to workers”.47 In his own economic writings, Harman was deeply influenced by this theme of the ageing of the system, even though he had demonstrated on the eve of the neoliberal era that it in no way contradicts the tendency to the internationalisation of capital. The growth in the size of capitals meant that, while the past few decades have seen the return of the “vicious circle” of boom and slump ultimately caused by low profitability, the destruction of capital on the scale required to restore the system to health has become too great to risk. Hence, particularly in the period since the Global Financial Crisis of 2007-9, the role played by the state (critically in the shape of the central banks) in keeping especially financial markets afloat with ultra-low interest rates and infusions of liquidity. The inflationary upsurge since the COVID-19 pandemic has greatly complicated the central banks’ task of economic management, but if anything, made it more important.48

After leaving the SWP, Kidron did not cease to be intellectually fertile. He came up with the brilliant idea of The State of the World Atlas (Pluto Press, 1981), using a familiar format to convey unfamiliar, often alarming truths about a globe heaving with conflict.49 In his later years, Kidron worked on a large manuscript that, in a less conventionally Marxist way, continued the critique of capitalism always at the focus of his intellectual preoccupations. Happily, International Socialism published an extract not long before his death in 2003.50

What place does military production occupy on this crisis-ridden system today? According to the International Institute of Strategic Studies,

[G]lobal defence spending reached $2.46 trillion [£1.8 trillion] in 2024, up from $2.24 trillion [£1.66 trillion] in 2023. Real-terms growth rose to 7.4 percent in 2024 compared to 6.5 percent in 2023 and 3.5 percent in 2022 … As a proportion of GDP, global spending increased from an average of 1.59 percent in 2022 to 1.80 percent in 2023 and 1.94 percent in 2024.51

This spending is substantially higher in real terms than the $120bn total Kidron reports for 1962, equivalent to $1.262 trillion (£934 billion) today. But it represents a much smaller percentage of global GDP than the 8-9 percent the military claimed then.

Rising productivity and output have reduced the economic burden that the arms sector represents for states, and therefore its ability to counteract the tendency of the rate of profit to fall. But the diminished relative economic weight of military production has not in any respect reduced the tremendous capacity for destruction with which it endows states, as we see in the wars Israel is waging against the Palestinians and between Russia and Ukraine—even without taking into account the capability to destroy humankind many times over that the nuclear powers retain. We still live in the shadow of mutual assured destruction. The rising figures for “defence” spending signal that we have entered an arms race unprecedented since the Cold War. This embraces not just higher spending by the Pentagon, but matching efforts by the West’s main rivals, China and Russia, the European rearmament drive, and the rivalries among regional powers at play in both the Middle East and Asia.52 So, it makes sense to revisit the efforts Marxists made during that earlier era to understand how the compulsive logic of inter-capitalist competition shapes the prospects for human survival.

Alex Callinicos is Emeritus Professor of European Studies at King’s College London, and a columnist for Socialist Worker. His latest book is The New Age of Catastrophe (Polity Press, 2023).

Notes

1 Weber, 1981, ch. XX, XXII, XXIII. This article was originally commissioned to introduce a translation of Michael Kidron’s article “A Permanent Arms Economy” in the French Marxist journal Contretemps—Callinicos, 2025. My thanks to Stathis Kouvelakis for commissioning the original article and translating it into French, and to Adrian Budd, Joseph Choonara, and John Rudge for their comments on drafts. The present version is slightly expanded and amended.

2 Callinicos, 2023, ch4.

3 Quadri, 2025.

4 Goldberg, 2025.

5 See Halliday, 1983, ch1.

6 The importance of the Third World as the arena where the Cold War was fought out is a major theme of Sergey Radchenko’s fascinating recent history of the Cold War from Russia’s perspective, see Radchenko, 2024.

7 Barker, 2022, p4.

8 Kidron, 1970, p11.

9 Barker, 2022, pp1-2, ch3, and Callinicos, 2009, pp169-178.

10 Quoted in Barker, 2022, p180.

11 The sole reference to Kidron is in a footnote that includes Western Capitalism since the War in a list of contemporary studies of postwar US capitalism; see Barker, 2022, p2, n6.

12 Cliff, 2003a, pp169-175.

13 Cliff, 2003b, p111; see generally, ch. 7, 8. See, on Cliff’s broader contribution, Callinicos, 1990, ch. 5.

14 I am indebted here to the excellent collection of Kidron’s writings edited and introduced by Richard Kuper with the assistance of John Rudge: Capitalism and Theory: Selected Works of Michael Kidron. His articles cited here are (with one exception) included in that collection.

15 Cox, 2019.

16 MacIntyre, 2023. Thanks to John Rudge for this reference.

17 Kidron, 1962.

18 Kidron, 1965.

19 I am grateful to John Rudge for pointing out Mike’s commitment to the Algerian struggle. For an alternative approach, much indebted to Kidron, that portrays capitalist imperialism as itself a historically evolving phenomenon, see Callinicos, 2009, esp. ch. 4, 5.

20 Kidron, 1969. This is a review of Mandel’s Marxist Economic Theory. In a subsequent and better work, Late Capitalism, Mandel does seek to address and account for the long boom.

21 Another ex-Marxist, Cornelius Castoriadis of the Socialisme ou barbarie group was another, more militant example of this tendency: see Callinicos, 1990, pp66-72.

22 Kidron, 1960.

23 Kidron, 1961. In what follows, I am indebted to Joseph Choonara’s excellent theoretical and historical exploration of Kidron’s theory: Choonara, 2021.

24 Kidron, 1960.

25 Kidron, 1974. On Marx’s theory of crises, see Callinicos, 2014, ch6.

26 Kidron, 1967,

27 Marx, 1981, p375.

28 Marx, 1981, pp363, 364 (translation modified).

29 Kidron, 1961.

30 Kidron, 1961.

31 Marx, 1978, p479. Marx restricts “productive consumption” solely to Department I, but his argument is clearer if the expression is extended to Department II(a), what he calls the “individual consumption” of working-class families. Kidron later devoted a study to the broader phenomenon of unproductive expenditure in late capitalism: Kidron, 2006.

32 Kidron, 1967.

33 Kidron, 1973. I am very grateful to Joseph Choonara for reminding me of this extremely brief and lucid text, published in the IS Internal Bulletin in March 1973, and not included in the Capitalism and Theory collection. (Mike’s original title for his text was “Every Talmud has a Torah, and every programme has a Yaffe”, which is funny but was deemed too obscure.) In his most widely cited statements of the PAE theory, Kidron confused matters somewhat by appealing to the claim by neo-Ricardian economists, notably Ladislaw von Bortkiewicz and Piero Sraffa, that the rate of profit in the luxury sector plays no part in the formation of the general rate of profit. This attracted the criticism of the likes of Yaffe and is quite unnecessary for his argument to work. For more on this, see Choonara, 2021.

34 Keynes, 1970, p378.

35 Barker, 2022, p8; see more generally, pp4-14.

36 Kidron, 1967.

37 Kidron, 1967.

38 Kidron, 1967.

39 Barker, 2022, ch5.

40 Kidron, 1970, Part 2.

41 Figures 18 and 19 in Barker, 2022, p408.

42 See the detailed account in Brenner, 2006.

43 See also Carchedi and Roberts, 2018. Adem Y Elveren and Sara Hsu, 2016, in a Marxism-inspired empirical study of 24 OECD countries find that military expenditure had a positive effect on profit rates in 1963-80 and a negative one thereafter, a result supportive of Kidron’s analysis.

44 Michael Roberts, 2025. Roberts’ misguided criticism is probably partly explained by his treating Kidron’s theory as an instance of military Keynesianism, which it plainly was not. Thanks to Joseph Choonara for this point.

45 Kidron, 1977; see also Kidron, 2019. This is the text (edited by John Rudge and with an introduction by me) of a talk Mike gave and the discussion it provoked at the SWP’s Marxism 1977 festival. There is much valuable material on Kidron’s political and theoretical shift during the 1960s and 1970s in the texts and editorial material provided by Kuper and Rudge in Capitalism and Theory.

46 Harman, 1977; Harman, 1984; Harman, 2009.

47 Kidron, 1973.

48 Callinicos, 2023, ch3.

49 For example, the first in the series, Kidron and Segal, 1980.

50 Kidron, 2002.

51 https://www.iiss.org/publications/the-military-balance/2025/defence-spending-and-procurement-trends/

52 Though this extra spending isn’t necessarily effective. As Adam Tooze, 2025, points out, “after spending more than $3tn over a decade, Europe really has been left with virtually no military capacity.”

References

imperial.htm

maginot.htm

insights.htm

defense-budget/