The advance of the far right internationally has disturbing echoes of interwar Europe.1 Just before Hitler’s National Socialist German Workers’ Party (Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei, NSDAP) came to power in 1933, the Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky wrote:

Any serious analysis of the political situation must take as its point of departure the mutual relations among the three classes: the bourgeoisie, the petty bourgeoisie…and the proletariat… When the social crisis takes on an intolerable acuteness, a particular party appears on the scene with the direct aim of agitating the petty bourgeoisie to a white heat and of directing its hatred and its despair.2

This article aims to apply Trotsky’s analysis to contemporary Western Europe. Mainstream thinkers believe that rather than class, a populist cultural backlash against liberal values explains the growth of the far right: “From the 1970s onwards…the erosion of old class structures undermined political bonds… The result of this development is the emergence of a new cultural cleavage”.3 In this scenario, populism is “a programme and communication in tune with voters’ priorities”.4 According to this narrative, migrants appear the pressing “legitimate concern” democratic politicians must surrender to.5

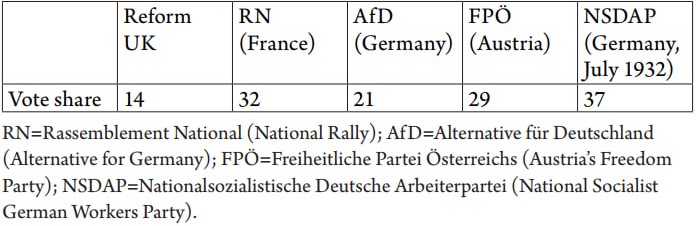

The scale and trajectory of far-right electoral support is undoubted. Table 1 compares elections during 2024-5 with the NSDAP’s best result in a free vote. France and Austria have long-established far-right parties. Those in Britain and Germany are newer.

Table 1: Vote share of far-right parties in Europe

However, it does not follow that populism is “in tune” with popular priorities. In the European Union (EU), surveys conducted twice annually since 1974 ask “What do you think are the…most important issues facing (our country)?”. Migration tends to score relatively high—and it led the list in 2015, during the summer of migration. Yet, when the 2015 survey replaced the word “country” and changed the question to “personally, what are the…most important issues you are facing?”, it clearly dropped. The new question elicited mainly personal socio-economic threats: prices, followed by household finances, health and social security, unemployment, pensions, taxation, education—and only then came immigration.6

In Britain this summer, frenzied rhetoric from Labour, the Tories and Reform UK, has pushed immigration to the top concern for “country” in one poll, while another poll found the cost of living, NHS, economy and crime ahead of it.7 The latest European survey puts immigration in third place for “country”, but it falls to 14th out of 15 as a personal priority.8 Another survey question measures individual discrimination: 91 percent say they treat people equally against 7 percent who say they do not. In Marine Le Pen’s France and Georgia Meloni’s Italy, the results are even better—93 versus 5 percent.9 One writer concludes: “Despite a rise in populism on the continent, Europeans seem to be getting more liberal”.10

This dichotomy between political trends and mass priorities reveals a battle to implant ruling-class ideology into the thinking of the working-class majority. One weapon used to legitimise capitalist needs above voters’ concerns is parliamentarism (though this is not an argument against revolutionaries standing).11 Apparent free choice notwithstanding, the agenda is framed to induce workers to vote for parties openly indifferent to their interests. Hence, since 1884, workers have been a majority of Britain’s electors, yet in the 125 years since its founding, Labour has led governments for only 27 years. For Germany’s Social Democratic Party (Sozial-Demokratische Partei Deutschlands, SPD), once the strongest social democracy, it is 29 out of 150 years.

The current upsurge in racism and reaction began after profit rates fell around 1970.12 To hide the fact that popular priorities like living standards are secondary to establishment politicians’ overriding priority—the maintenance of capitalism—minorities were presented as the major problem. The more intractable the crisis, the more the lies and scapegoating are ratcheted up. Refugees in small boats are demonised here, but every country has its spurious moral panics. Centre parties launched this racist auction but lose to whoever is most anti-immigrant. In a topsy-turvy world, the needs of a tiny super-rich minority come first, far-right voting eclipses public preferences, and the masses are unjustly reproved for ditching socially liberal values.

If actual levels of immigration explained votes for the far right, they would mirror each other. Yet, studies find no positive correlation. In French local council elections, far-right votes do “not depend in any way on the prominence of the foreign population”.13 People “are more favourable to immigrants when the proportion of resident foreigners is high, and all the more “racist” when it is low”.14 In 2024, England’s most ethnically diverse region, London, registered Reform UK’s lowest percentage, and the North East, the least diverse, its highest.15 No correlation exists at national scale between immigration and populist voting either.16 Hungary has a miniscule refugee population but one of the highest levels of anti-refugee sentiment in Europe.

The Petty Bourgeoisie

As in the 1930s, the current situation should be understood through class, with petty bourgeois politics playing a particular role. This class comprises “shopkeepers… tradesmen (i.e., builders, electricians, plumbers, etc.), publicans, small landlords, freelancers, farmers, hairdressers and many more besides”.17 Early on, Herbert Kitschelt noted the far right appealed to the petty bourgeoisie of France, Denmark, Austria and Italy.18 Jens Rydgren found: “Empirical research clearly shows that…the old middle classes are indeed overrepresented among new radical right voters”.19 Ronald Inglehart and Pippa Norris agree: “populist voting was strongest among the petty bourgeoisie”.20 It is above-average in the fascist Alternative for Germany (Alternative für Deutschland, AfD).21 A Socialist Worker undercover investigation completes the picture. At one Reform meeting:

[T]he speaker asked who in the room is a small business owner—roughly four in ten hands went up. Most of the speakers were small business owners too. It points to Reform UK being powered by a revolt of the small capitalists.22

Nonetheless, at roughly one in ten of Europe’s working age population, the petty bourgeoisie is too small to explain the size of far-right polling.23 Insofar as parties are expressions of ideology rather than of their social composition, the exact proportion of the petty bourgeoisie in far-right ranks is not decisive, however. The petty bourgeoisie was four out of ten Germans in the 1930s, yet most Nazi votes came from elsewhere.24 The ruling class is miniscule, and it still dominates the discourse of most parties.

Europe’s petty bourgeoisie has not always played a reactionary role. Once very large, it was the vanguard of the 1640 English Revolution (the Levellers) and of the 1789 French Revolution (sans-culottes). Today, a diminished petty bourgeoisie sits alongside a “new middle class” of supervisors and managers but unlike them, is not an intermediary between labour and capital. Its enterprises are petty (small) aspiring to be big, and so it apes big business ideology. A disparate bunch of individuals competing inside national borders, the petty bourgeois sense of identity comes from a xenophobic patriotism. It denies the relevance of class and class division, subsuming them into the concept of nation. How this mentality is expressed depends on circumstances.

While the post-WWII boom lasted, the petty bourgeoisie was the backbone of centre-right parties. Afterwards came falling profit rates, crisis and neoliberalism so that “global inequality between the top and the middle of the distribution increased, but it declined between the middle and the bottom”.25 In Britain, the proportion of national income going to the top 1 percent tripled between 1980 and 2005.26 The petty bourgeoisie faces crushing competition from corporations, online merchants such as Amazon, large high street chains, mass production and cheap imports. No class is monolithic, but significant sections angrily splintered from established parties to constitute an autonomous pole of attraction in the wider party universe.

How this manifests itself is important for tailoring counter-strategies.27 Hitler’s Nazis began as a militia and turned to parliamentarism later. Some far-right leaders have associations with this past. Others do not. Today, the emphasis is mostly electoral, though events in Britain show no wall separates parliamentary and extra-parliamentary far right agitation. Policies range from economic libertarianism to state authoritarianism, respectability to radicalism, beer-swilling joviality to menace.28 Much academic effort is devoted to categorising this: “neo-fascist”, “far right”, “radical right”, “extreme right” or “populist right”. Cas Mudde wins the prize, finding 26 types with 56 ideological features.29 Beneath the variations, the petty bourgeois perspective—an exaggerated and dogmatic form of capitalist ideology—infuses far-right politics.

The ruling class takes a more instrumental approach towards its own creed. As Lord Palmerston, a former British prime minister, put it: “we have no perpetual enemies. Our interests are eternal”. Global business exploits people and resources everywhere while political acolytes glorify “our nation” and stigmatise “outsiders”.30 Tensions exist between ideology and pragmatism, politics and economics, as with Trump’s tariffs or Brexit, but compromise is possible, sometimes under pressure from workers and the oppressed.

Wrapped in the flag, modern far-right parties bristle against such flexibility. To them, promoting racism and oppression feels fundamental, not expedient. Driven to fury by the establishment, anger is overwhelmingly against its scapegoats. Britain’s August 2024 pogrom witnessed no attacks on banks or corporate headquarters. Rage punched downwards, against mosques and refugee hotels.

Petty-bourgeois extremism can call upon extra-parliamentary forces unavailable to the ruling class and the state. Hitler’s two million brownshirts were a counter-revolutionary sledgehammer.31 Ironically, once they had crushed the workers’ movement, he massacred their leadership and let corporate capital run riot. A major contraction in petty-bourgeois numbers followed. To mollify supporters, Hitler resorted to increasingly grotesque measures in a process dubbed “cumulative radicalisation” that ended with Auschwitz. It was the fatal mistake of the 1930s German left—Communists and Social Democrats alike—to focus on internal rivalries and underestimate the danger. For the moment, ballots usually predominate, but the firebreak of revulsion against fascist violence is not unbreachable, and ongoing crisis gives the far right space to spread poison in the streets, at work and in the pub. 32

Far-right workers’ parties?

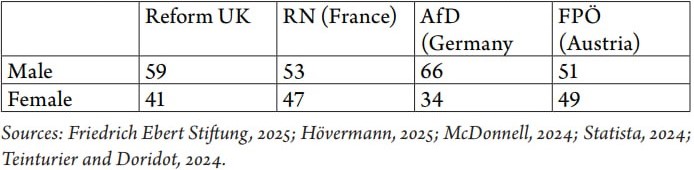

Support for the far right is wider than the petty bourgeoisie. Studies of 2024-5 elections show four regular features and are covered in tables 2 to 4. Firstly, most votes came from men.

Table 2: Male and female votes for selected far-right parties (percentage)

Greece’s Neo-Nazi Golden Dawn had an extraordinary 74/26 male/female ratio. The imbalance is partly due to ideology. The twisted logic of the enraged petty bourgeoisie was seen in Britain’s August 2024 fascist riots claiming to defend “our” women and girls from Muslims and migrants. The sexist nature of capitalist society encourages attacks across all communities and 41 percent of arrested rioters had been reported for domestic abuse.33 Additionally, many male industrial workers vote for the far right for structural reasons (see below).34

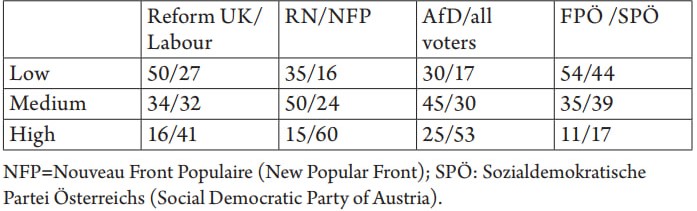

Secondly, on average, far-right voters are less qualified.

Table 3: Educational attainment (percentage)

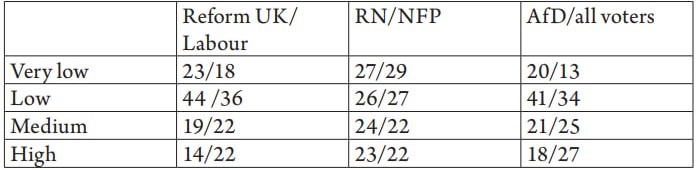

Thirdly, they earn less overall.35 They are poorer than Labour supporters, as poor as France’s radical left, and substantially worse off than the average German voter. Likewise, Austria’s Freedom Party (Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs, FPÖ) polls better in lower income brackets.36

Table 4: Income levels (percentage)37

Finally, and linked to that, blue collar workers are prominent. The ratio of Reform voting manual workers and poor to managers, professionals and clerical grades is 65/35. Labour has a more even structure, 48/52.38 In France, manual workers are 37 percent of the vote for the National Rally (Rassemblement National, RN) compared to 17 percent of the NFP’s.39 The AfD’s blue-collar share is twice the public’s. As for the FPÖ, 44 percent of voters are manual workers, 28 percent white collar and 27 percent petty bourgeois.40

A superficial reading of such statistics concludes the far right is “proletarised”.41 For Didier Eribon, the French working class has “found a new way to organise itself and to make its point of view known” through the far right, the only party “that seemed to care about them [and] offered them a discourse that seemed intended to provide meaning to the experiences that made up their daily lives”.42 This is “class war carried out at the ballot box”.43 Germany’s AfD has been classified a “post-industrial workers’ party”, and Farage declares Reform the “party of the workers”.44 Urged on by the Blue Labour think-tank, Keir Starmer seems convinced of moving rightwards to “reconnect” with voters.45

Some on the left are also influenced by this conception. Rather than understanding the reactionary core appeal of the far right, they hope to win back workers by relating only to the economic and social distress of those drawn towards it. So, they avoid exposing its racism. In Britain, this goes along with playing down “woke” issues and not shouting “Nazis out” when the far right threatens refugee hotels because not all the participants are ideologically hardened Nazis. If the far-right threat is to be opposed, its fundamentally racist and reactionary nature must be called out.

Furthermore, the idea that the far right is “proletarised” is itself false. Firstly, workers back many parties because consciousness is shaped by the interaction of the prevailing ideas and the experience of exploitation—which varies widely. At one end of the spectrum, workers who support far-right petty bourgeois politics identify with a nebulous “nationhood” that negates class.

Secondly, if a party receives workers’ votes that does not mean it stands for them. Lenin wrote, “whether or not a party is really a political party of the workers does not depend solely upon a membership of workers, but also upon [those who] lead it, and the content of its actions”.46 Before Hitler smashed all working-class organisation, 58 percent of his supporters were workers.47 Nowadays, some low-qualified men trapped in poorly paid manual labour blame women or ethnic minorities and vote for the far right. This does not lend “meaning to the experiences that made up their daily lives”.48 Bosses set pay levels, not refugees. Workers under the spell of manipulative propaganda do not represent their class.

Thirdly, some far-right support comes from protest voting. The conventional party system is breaking down, some arguing: “the establishment offers us nothing, so we’ll give someone else a go”.49 Their vote does not change the far right’s petty-bourgeois ethos. Britain illustrates the phenomenon. Nigel Farage’s UK Independence Party (UKIP), precursor to Reform, promoted Brexit in classic petty-bourgeois terms. Though marginal to working-class preoccupations, when Brexit became seen as a means to kick the establishment, UKIP support exploded: from 3.1 percent (2010) to 12.8 percent (2015). In 2017 (after the referendum), it crashed to 1.8 percent. One third simply abstained, Labour’s Jeremy Corbyn attracted more than those who still backed UKIP, and four times that number went Conservative.50 In 2019, these helped push Labour to its worst result since 1935. In 2024, the Tories suffered their worst defeat in history when the protest vote jumped ship again—back to Farage. In Scotland, Reform gained half the share of voted it managed to gain in England because the Scottish National Party (SNP) had previously captured protest votes, though this took the form of rejecting Westminster government. Nonetheless, if unaddressed, over time the protest voter of today becomes the committed far-right voter of tomorrow.

Finally, the proletarisation thesis wrongly assumes workers who vote for the far right are typical. Classes are in a continual process of change, and as we shall see, the working class is larger, more multigender and more multiethnic than what this thesis assumes. It also goes beyond manual workers.51

Yet, sections are clearly vulnerable, because the pain of capitalism is unevenly shared, and class struggle has been generally low. For example, West European industrial employment halved between 1950 and 2014, over 6 million jobs disappearing after 2000.52 Those in manufacturing found it harder to protect pay and conditions. Sometimes the phrase “the left behind working class” is used, although this mistakenly suggests everyone else is fine.53

In Germany, this process was concentrated in time and place.54 In 2025, the AfD scores about twice as high a percentage in Eastern Germany as in Western Germany.55 Dreams that unification meant luxurious living standards evaporated after East Germany’s uncompetitive industry collapsed overnight. Swarms of “job nomads, low-wage earners, seasonal commuters, casual workers” and unemployed were created.56 In some areas, a quarter migrated westwards, many being women with non-industrial skills. 57 With politics focused on “the return of the German nation” “a portion of wage earners began to internalize the right-wing populist axiom, a worldview that would henceforth seem spontaneous”.58 They became obsessed with workers who were migrants too, but from further afield. This was despite the East having one third the ethnic minority density of the West and lower wages (giving the lie to the idea immigration depresses wages).59 Fantasies about immigrants do not depend on truth. They gain purchase with workers by feeding on real deprivation and lack of belief in the class’s ability to fight back.

Far-right support in such circumstances was not inevitable though. Unlike the petty bourgeoisie, which pictures itself as part of the system (even when it undermines them), workers’ experience (including white, male and manual) tends to contradict claims capitalism is the best there can be. Poverty, oppression, exploitation and inequality cut through the “we are all in it together” mantra. Workers fend off the bosses’ worst excesses through struggle and union organisation. If a working-class culture exists, this is it. So, why adopt a petty bourgeois mentality instead?

The fact that Social Democratic leaders embraced right-wing and racist policies before far-right voting took off is telling. Predictably, during the boom years after the Second World War, centre-right parties were prone to divide and rule tactics, while reformism, left and right, talked of progressive change framed within “the national interest”. However, when the boom ended, bolstering capitalism and diversionary tactics took precedence all round.

Labour’s Tony Blair whipped up Islamophobia to justify the 2003 Gulf War. Gordon Brown, his successor, borrowed the British National Party slogan of “British Jobs for British Workers!”. From less than 2 percent support in the early 2000s, the BNP scored around 12 percent in opinion polls a decade later. Jeremy Corbyn’s attempt to buck the trend was sabotaged internally.

When French Socialist François Mitterrand became president in 1981, far-right Jean-Marie Le Pen was on 0.2 percent. In 1986, to undercut mainstream rivals, Mitterrand altered electoral arrangements to favour him. He got 9.6 percent that year.60 In 2003, the SPD brought in the Agenda 2010 benefits changes that depressed wage growth until 2012.61 The AfD launched a year later. In 1970, Austria’s Social Democrats struck a deal with the FPÖ to support their minority government and formed a full coalition with it in 1983. Seven years later, the FPÖ vote had tripled.

Greece’s Golden Dawn stood at 0.1 percent in 1996. During the early 2000s centre-left Panhellenic Socialist Movement (Panellínio Sosialistikó Kínima, PASOK) met EU fiscal rules to join the Eurozone by imposing deep cuts, particularly in health, and turned on the racist tap. By the end of PASOK’s 2009-2015 government, Golden Dawn had 7 percent. During the 1980s recession, the Dutch Socialist Party reduced public spending by a quarter and argued native workers were threatened by immigrants with an alien culture. This cleared a path for Geert Wilders’ Party for Freedom, founded in 2004.

Social democratic leaders do not blame their record for far-right expansion, but they blame their followers. In fact, new supporters are mainly disgruntled centre-right voters looking for an alternative home. They see no benefit to voting for a centre left that offers so little and whose leaders’ rhetoric makes anti-immigration policy seem so crucial. Overall, “less than 20 percent of new voters of radical right parties switched from a social democratic party”.62 Tracking specific elections confirms this.

In 2024, the Tories lost 23 percent of voters to Reform, whereas Labour lost just 3 percent.63 In the 2017 French presidential election, social democracy collapsed from its previous 52 percent to 6.4 percent in the first round. In the next round, only 3 percent of this went to Le Pen; 70 percent went to Emmanuel Macron.64 The SPD slumped in the 2025 German election, but 71 percent of vote switching to the AfD came from non-left parties. SPD voters mainly transferred to the conservative CDU/CSU.65 Austria’s 2024 election confirms this trend: The FPÖ vote share increased from 16.2 to 28.8 percent, but the SPÖ lost only 0.1 percent (from 21.2 to 21.1).66

Social democracy is in trouble, but for a different reason to their leaders’ claims. When reforms were delivered in the post-war period, it was rewarded with loyalty. After these dried up, the bond was broken. In Britain, for example, Labour won the 1964 general election with 73 percent of the trade union vote. By 1983, it was only 39 percent.67 Between 1990 and 2020 European social democracy’s vote share fell from 30 to 16 percent.68 This measures the degree to which social democratic leaders walk away and openly back the enemy. It is not a sign of rank-and-file defection to the far right.

Potential for resistance

Readers could be forgiven for thinking the situation is bleak. Yet, we should not be mesmerised, because the basis for a mass anti-racist and anti-fascist politics exists. What academics call the “disappearance of class” is the turbulent, alienated assertion of very real classes faced with a political system that stands with the super-rich.

The result is polarisation. The petty bourgeoisie breaks rightwards dragging many with it, but potential for working-class resistance and revolution also grows. Far-right successes in polling booths every few years compete with a thirst for meeting genuine needs and ongoing struggles by trade unions, campaigns, communities and individuals.

In the tussle, parliamentarism loses legitimacy.69 A survey in the countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) reveals 44 percent have “low or no trust in the national government” and those who think this are often “financially insecure [or have] low levels of education”.70 This is the demographic of the far-right vote. But loss of trust also leads to abstention.71

The net reduction in voter numbers since the 1970s exceeds Britain’s far right by two to one, while equalling it in France and Germany. In 2022, 46 percent of Italians abstained. Meloni was elected by just 26 percent of the remainder—1 in 6 of those eligible to vote. Performing the same calculation on Reform UK at the 2025 English council elections (30 percent of the vote on a 34 percent turnout) gives one in ten of the population. Party fragmentation (with more candidates standing) also meant the percentage needed to clinch a seat was the lowest ever, at 41 percent.72 In 2024, 87 million US abstainers comfortably beat Trump’s 77 million.73 Many, including those who fit the far-right electoral profile, do not support it.

Abstainers are not necessarily politically disengaged or apathetic. For example, “the historically low voter turnout rate of the [French] 1969 presidential election followed the greatest social uprising in modern French history”.74 Today, abstention accompanies mass movements over climate change, Black Lives Matter, trans and women’s rights, Palestine, and more. These dwarf what occurred in the heyday of parliamentarism.75 Since 2006, the number of protests worldwide has tripled: “We are living in an age of global mass protests that are historically unprecedented in frequency, scope, and size”.76

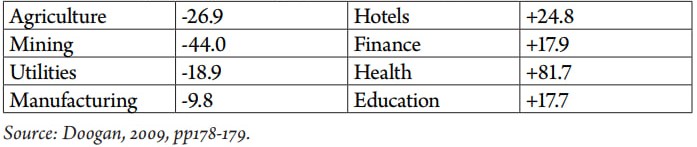

Furthermore, proletarisation is not as imagined by those for whom only blue-collar work counts. Over decades, new groups are being added while some more susceptible to voting far right shrink.

Table 5: Percentage change in employment in the EU 1992-200277

Expanding areas of work attract a high proportion of women.78 Those with an educational advantage may command better incomes, yet many know they are exploited.79 Britain’s well qualified workers are “a significantly higher proportion [of trade unionists] than all other employees with lower levels of educational qualification”.80 Workforces that once stood aloof from class struggle, such as universities, schools and hospitals, are now as proletarian as anyone else:

[T]he working class constitutes an increasingly diverse and progressive group in the twenty-first century. Although women and people with a migration background are more prominent among the “new working class” of service workers… a significant minority of the “old working class” of production workers is neither white nor male. And in terms of attitudes, the vast majority of both production and service workers hold progressive views on LGBT issues, while a large share holds progressive or neutral (and therefore not very strong) attitudes on immigration.81

Clearly, forces exist to be mobilised. Social surveys (whose samples are majority working-class) show how big these forces are. Countries in the “most favourable to immigration” category of the Europe-wide Social Survey rose from three in 2002 to eight a decade later.82 Although opinion polls show France’s RN riding high, surveys suggest “there is no sign of a long-term move to the right. Rather it is the inverse that is seen”.83 A 2024 British Social Attitudes report finds: “attitudes to immigration and its impacts have become much more positive… In 2014, 30 percent thought that immigration had a positive impact on the economy; by 2020/21 this figure had increased to 59 percent”.84 The report noted the same trend applies across Europe. Favourable attitudes to immigrants who are here can co-exist with wanting reduction in immigration by others unknown.85 We are back to the vote versus priority, ideology versus experience, dichotomy.

None of this leaves room for complacency.86 The far right is rising and is dangerous. Elections are biased, but who heads the state matters. Starmer’s government is a disaster that encourages the far right. Fascist street violence can erupt very quickly. Latent resistance is not active opposition. Irrational conspiracy theories and blatant falsehoods can insulate people from reality and reverse progress. In struggles between division and solidarity, the outcome is not fixed. Strategy based on class is decisive.

Strategies

If culture rather than class factors really explained the far-right surge, tougher immigration rules should dissipate rather than increase support. It is claimed that Margaret Thatcher’s racist speeches and policies destroyed the National Front in the early 1980s.87 That honour lay with a working-class united front, the Anti-Nazi League.88 Thatcher’s antics, parroted by Labour leaders, laid the ground for the British National Party and Reform. A study of 350 European centre parties across 108 different elections finds “voters are on average more likely to defect to the radical right when mainstream parties adopt anti-immigration positions”.89 Jean-Marie Le Pen noted voters “prefer the original to the copy”.90 Centre-left and centre-right politicians do not deliberately aid their far-right electoral nemesis, but they are functionally incapable of stopping themselves. Tied to rescuing capitalism by peddling the divisions it needs, they unintentionally commit political suicide.

The popular front appears to be an alternative tactic: a cross-class coalition of the left and centre to exclude the far right from office. However, this approach from the 1930s is a failure. Mainstream leaders may verbally criticise far-right electoral rivals, but they still promote the capitalist agenda fuelling them. As Denis Godard showed in a previous issue of this journal, the popular front disarms anti-racists and the working-class fightback.91

Trotsky’s class approach is a far better basis for devising strategy. The petty bourgeois ideology of the far right is a specific threat to the working class. It is reproducing a 21st century equivalent of developments seen during interwar Europe’s social crisis. Racism is the ideological vehicle for grievance—but one whose aim is to counter a class response to the crisis—to act as a battering ram against the left and social movements.

Explicitly or implicitly racist and “anti-woke” by turns, the far right poses as a “normal” political alternative to hide its true role.92 If right-wing extremism sneaks through as merely cultural or acceptable, its appeal will diversify. Take Nadine, a black woman born in the Congo living in a French women’s refuge with her four young children. She says: “How can you say it’s racist to vote for [Marine Le Pen]? If I was entitled to vote, I would vote for her to get the country in order, because Africans are abusing things”.93 The AfD enjoys some backing from second-generation migrants.94 There are Serbs in Austria who vote for the FPÖ to exclude Muslims who they see as rivals. In the Netherlands, Wilders has support from Surinamese-Dutch Hindustanis accepting lies about people with a Turkish or Moroccan background. In Italy, almost as many women now vote for the far right as men.95 Reform UK polled half as well among ethnic minority voters as it did with the general public—the figure was not zero.96

The petty-bourgeois national illusion leads the far right to believe it is the people. Mobilising large-scale anti-racist and anti-fascist working-class opposition can burst that collective bubble and demoralise followers. Workers who support the far right should be treated as the political equivalent of scabs in a strike. These are dealt with by a picket line whose main purpose is to stop strike-breakers getting through, while persuading them to change. It takes patient, hard work to build a picket line, but the bigger the turnout, the more convincing it is. The type of argument for mobilising to counter the far right is that: 1) racism is morally repugnant; 2) fascism is a genuine danger; and 3) victimising scapegoats for social problems they are not responsible for perpetuates these problems and derails campaigns to alleviate them.

In isolation, campaigns based on pure moralism, references to the 1930s or economism are insufficient. Progressive campaigners and trade unionists should realise how much their cause is weakened if the far right is not confronted. If workers think they are poor, homeless or lack services because of someone in a dinghy in the Channel, pay, housing and services will not improve. Every sexist, homophobic, transphobic and disablist comment divides our class and aids the bosses.

What happened in the London docks shows how to turn the tables. In 1968, dockers struck in support of Tory Enoch Powell’s racist speech. However, consistent anti-racist work by socialist dockers along with agitation over economic grievances meant that when the dockers fought in 1972, they led the British working class to the brink of a general strike, clinching a famous victory against a Tory government.97

The oppressed are the first but not the last in the firing line. Mutual defence depends on solidarity. France shows the dangers of separation. The working class is militant on the economic front but has avoided confronting Islamophobia masked as upholding “laicité” (secularism). So, the RN has grown. If the working class fails to grasp the need to fight oppression, or vice versa, if identity politics creates a barrier to unity with workers, that is self-defeating.

A long history, from London’s Cable Street in 1936, through occupied Europe’s resistance movements, to the Anti-Nazi League and Stand up to Racism’s quelling of the August 2024 pogrom, shows the mechanism for resisting the far right is the workers’ united front. This brings together trade unions, campaigns, oppressed communities and political currents from reformist to revolutionary. The mechanism for ending its periodic regeneration is revolution led by a party committed to that goal. Our class has the size, power and motive to defeat barbarism in all its forms.

Donny Gluckstein is a Socialist Workers Party member whose publications include The Radical Jewish Tradition (with Janey Stone, Bookmarks, 2024), The Nazis, Capitalism and the Working Class (Haymarket Books, 2012), A People’s History of the Second World War (Pluto Press, 2012) and, as editor, Fighting on All Fronts: Popular Resistance in the Second World War (Bookmarks, 2015).

Notes

1 Thanks are owed to Leandros Bolaris, Joseph Choonara, Richard Donnelly, Manfred Ecker, Rob Ferguson, Jacqui Freeman, Penny Gower, Despina Karayianni, Mark Kilian, Charlie Kimber, Sheila Macgregor, Carlo Morelli, Tony Phillips, Gianni del Pianta, Eddie Prevost, Sascha Radl and David Reisinger.

2 Trotsky, 1993, p6.

3 Norris and Inglehart, 2019; Delespaul, 2025.

4 van Haute and others, 2024.

5 Even Perry Anderson seems to believe there is “a problem of immigration”—Anderson, 2025. China Miéville, 2025, effectively counters this.

6 Eurobarometer, 2015.

7 YouGov, 4 August 2025; ONS, June 2025.

8 Eurobarometer, 2025.

9 Eurobarometer, 2023, p25.

10 Ulea, 2023.

11 See Choonara, 2023.

12 See Roberts, 2022.

13 Mayer, 1999 p 252. See also Mudde, 2007, pp212-3, and Le Bras and Warnant, 2021.

14 Quoted in Mayer, 1999, p 260.

15 Cracknell and Baker, 2024, p15, and UK Government, 2021.

16 Mudde, 2007, p212.

17 Evans, 2023, p32.

18 Kitschelt, 1997, pp102, 135, 145, 177, 189.

19 Rydgren, 2007, p249.

20 Inglehart and Norris, 2016, p4.

21 See Becker and others, 2018, p136.

22 Foster, 2025.

23 CEDEFOP, 2023; Espinosa, 2024.

24 Gluckstein, 2012, p88.

25 The dates in question are 1980-2020. Global inequality, 2022.

26 Umney, 2018, p42.

27 See for example Choonara’s fourfold definition in Choonara, 2024, and Ali and Nielsen, 2024.

28 See authors like Kitschelt and Mudde for discussions of this.

29 Bruter and Harrison, 2011, p5.

30 See for example Georgi, 2024.

31 See for example Allen, 1973.

32 See Callinicos, 2023.

33 Cuffe and Gregory, 2025; Murray and Syal, 2025.

34 See also Hardy, 2021, Ch 7.

35 See also Ciccolini, 2025; Dassonneville and McAllister, 2023, pp20-21; Stoetzer and others, 2021.

36 Rybak, 2019.

37 Britain: annual household income £20,000-£49,999, £50,000-£69,999, over £70,000; France: monthly household income under €1250, €1250-€1999, €2,000-€2999, more than €2.999; Germany: monthly household income of less than €1,500, €1,500-€2,499, €2,500-€2,999, €3,000 and above.

38 McDonnell, 2024.

39 Teinturier and Doridot, 2024.

40 Statista, 2024.

41 See Mudde, 2007, p17.

42 Eribon, 2018, p128; Eribon, 2018, p124.

43 Eribon, 2018, p129.

44 Becker and others, 2018, p140; Maddox and Mitchell, 2025.

45 Peston, 2021 and Syal, 2025; See for example Oush, 2025.

46 Lenin, 1959, p460.

47 July 1932. Gluckstein, 2012, p86.

48 Eribon, 2018, p124.

49 See for example Crewe and others, 1977. Mayer talks about “ninistes” in the far-right French electorate, who consider themselves neither (“ni”) on the right nor (“ni”) on the left. Mayer, 1999. This was heard on the doorstep from people considering Reform when canvassing for a socialist recently.

50 Kellner, 2017.

51 See Abou-Chadi and others, 2021, pp11-15.

52 EU Commission, 2018.

53 A study of Austria’s Freedom Party finds it did best “where the losers of modernization are particularly exposed”—Jansesberger and others, 2021.

54 See Radl, 2025, for a more detailed analysis of crisis in Germany and the rise of the AfD.

55 Statista, 2025.

56 Mau, 2019, p161.

57 Mau, 2019, p191.

58 Mau, 2019, p 210; Becker and others, 2018, p 58.

59 Bevölkerung und Erwerbtätigkeit, 2019, p68. Average earnings are 15 percent higher in West Germany. (IFO, 2023). In England are lowest in the North-East and highest in London. (Average earnings by age and region,2024). See also Le Bras and Warnant, 2021.

60 Mudde, 2007, p225.

61 Average annual wages, 2024.

62 Abou-Chadi and others, 2021, p 18.

63 Ashcroft, 2024. A Persuasion UK report shows 74 percent of those who voted Reform in 2024 had never voted Labour previously. (Akehurst, 2025).

64 Clarke and Holder, 2017.

65 Tagesschau, 2025.

66 See Walker, 2024.

67 Cliff and Gluckstein, 1988, p383.

68 Abou-Chadi and others, 2021, p5.

69 Ansell, 2022 p13.

70 OECD Survey, 2024.

71 Ledgerwood, 2024. See also Ansell who reports “a robust relationship between inequality and overall turnout…in 21 advanced democracies”—Ansell, 2022, p6.

72 See Local election, 2025.

73 Lindsay, 2024.

74 Vugdalic, 2022.

75 See Tiberj, 2024, p174.

76 Ortiz and others, 2022; Stirling and others, 2020.

77 Doogan, 2009, pp178-179.

78 See More people in work, 2022.

79 For details see Giupponi and Machin, 2022, figure 19.

80 Newson, 2023.

81 Abou-Chadi, 2021, p15; see Hardy, 2021. The Birmingham bin workers are a good example.

82 European Social Survey, 2017, p14.

83 Tiberj, 2024, p23.

84 Ford and others, 2024, pp4, 10.

85 See for example Migration Observatory, 2011.

86 See for example Kranebitter and Willmann, 2024, p8.

87 Ignazi, 2003, p180.

88 See Brown, 2025.

89 Brown, 2025.

90 Krause and others, 2022.

91 Godard, 2025.

92 Reform’s Edinburgh council election leaflet promised improved services, fewer potholes, and more housing. There was no mention of immigration. Elsewhere some are full of racism.

93 Dahani and others, 2023, p39.

94 Becker and others, 2018, p76.

95 Puleo and others, 2022.

96 Abraham and Smith, 2024.

97 Prevost, 2025.

References

not-vote

n07/letters

net-migration