Capitalism has placed humanity on a devastating collision course with living nature.1 In its 40-year neoliberal phase alone it has unleashed a scale of ecological destruction that has few precedents across Earth’s entire geological history—we are teetering on the brink of a sixth mass extinction event. While we are not short of examples of the horrors unleashed by capitalism, this wanton destruction of non-human life in its myriad and amazing forms is surely one of the most obvious markers of our descent towards barbarism.2

The unrelenting ecological degradation of the neoliberal era is all the more alarming when we reflect that organs of environmental resistance have been flourishing during this period. Environmental NGOs and pressure groups now number in their hundreds across the world and membership numbers are higher than those of most mainstream political parties.3 While the situation for biodiversity would be worse in the absence of these groups, their work and occasional victories have failed to stem the tide of extinction and ecological devastation derived from capitalism’s accumulation process.

For environmental conservationists the frustrations and growing awareness of the scale of the challenge have lately led to some surprising tactical and philosophical directions that have been discussed previously in this journal.4 In particular, the drive to assign monetary value to biodiversity and nature is being portrayed as a necessary means of translating the environmental message to legislators, business and the markets. This argument for nature financialisation—the processes by which banks and financiers have turned to environmental conservation as a new front for speculative investment, and the simultaneous rewriting of conservation to fit banking and financial concepts—has gained momentum and acceptance across environmental science and politics during the last decade as economic recession/depression and austerity have dominated global economic architectures.

The concept of “natural capital” (NC) that has developed through this drift towards financialisation has now taken firm and favourable root within mainstream environmental politics. Essentially, in the spirit of the old Quaker maxim “speak truth unto power”, some environmentalists are presenting the need to assign monetary value to biodiversity, ecology and nature as a form of political pragmatism. Critiques of NC within conservation, meanwhile, are being suppressed through false consensus and the well-rehearsed Thatcherite TINA—“there is no alternative”—mantra.

Modern campaigning environmentalism can trace it roots back to the social and political movements that erupted 50 years ago. Organisations such as Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth rose directly from the anti-Vietnam War movements to challenge the ecological destruction that was being revealed across the world during the 1960s and early 1970s.5 Alongside direct action and the development of ecological science, many environmentalists embarked on a quest for alternative and counter-cultural or anti-capitalist values. Native American history and culture provided a particularly rich seam of influence for environmental romantics and the ecological elements of individualist lifestyle politics. A poorly-translated and Hollywood-manipulated “speech” by Chief Si’ahl (Seattle) was particularly popular, and one suite of questions in the speech was for many decades held aloft as a central ethic within environmentalism: “How can you buy or sell the sky, the warmth of the land?… If we do not own the freshness of the air and the sparkle of the water, how can you buy them?” Today, almost a half-century later, it is astounding to think that the answers to these profound (if sadly apocryphal) questions have come from within environmentalism itself. For today’s neoliberal or pragmatic environmentalists, the answer is natural capital.

Natural capital

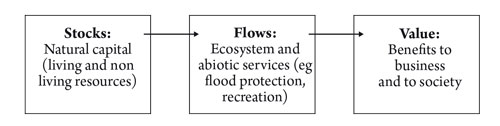

Natural capital can be interpreted as a concept in which, “nature and the ‘natural world’ [are] approached in terms of asset values for human organisations and societies that can be calculated in monetary units using economic and accounting techniques”.6 It represents an increasingly popular attempt on the part of certain environmental economists to identify and apply mainly quantitative, financial values to the components of ecology that underpin human society. The species, habitats and ecosystems that constitute society’s natural capital provide various and wide-ranging “ecosystem services”—ranging from indirect or generalised services such as water quality, to direct and specific services such as fishery yields. The condition of these units as defined in qualitative and quantitative terms, represent the “stock” of natural capital (figure 1). Monitoring of the stock’s condition can be achieved through the development of natural capital accounting tools, and the outputs of these are increasingly used to determine the state and trajectory of biodiversity under prevailing economic and policy conditions.

Figure 1: The natural capital framework

Source: Natural Capital Coalition, 2016.

The approach has been developed by environmental economists who are concerned by the general failures of capitalism’s price allocations for biodiversity, ecology and ecosystems. In the current system, environmental degradation appears as a so-called market “externality”—in other words, it doesn’t represent a direct financial cost to the polluter. Instead, NC identifies the value of these hitherto economically-hidden elements of society, helping states and businesses to quantify their ecological impact and steer their policies accordingly. An effective NC approach relies on acceptance of a framework in which monetary value is assigned to nature to a maximum feasible degree (full financial valuation is tempered with a slight nod to “ethical” considerations).7

The historical response to biodiversity loss

Before outlining the problems with NC it is worth considering how the concept fits within the historical landscape and politics of environmental conservation. Prior to the 1960s, species conservation was influenced mainly by a philosophy of wilderness romanticism. The poetic narrative embedded in influential work by the likes of Aldo Leopold and John Muir in the US, and Gilbert White and Lord Rothschild in the UK, led to a land ethic dominated by the need to “protect” landscapes from human interference through partition into nature reserves and national parks.8

Thus, for the first half of the 20th century, ambitious attempts were made to carve out and preserve parcels of land for nature and wildlife. The most influential initiatives came from the US, where large areas such as Yosemite National Park were established for landscapes that appeared devoid of human interference but which had actually been wiped clean of indigenous influence by disease, war and racist land-grabs. Throughout Africa, European colonial powers created similar “game reserves” (with similar devastating cultural impact) to enhance wildlife populations for hunting and the “safari” culture. These reserves are today the source of amazing media images of “wild Africa” that feed Western appetites for wildlife conservation. But their artificial and often violent history is hidden from view.9

Across the USSR, the pre-revolutionary interest in nature reserve development was encouraged by Lenin and the Bolsheviks to protect vast swathes of land as zapovedniki—nature reserves that could serve the joint objectives of wilderness protection and scientific research.10 This latter approach entailed maintaining “natural” areas as comparative laboratories against land that was earmarked for agricultural and industrial improvement—a more rational methodology that saved much of the former USSR’s biodiversity from post-war industrialisation but which is now threatened by market capitalism across Russia today.

Environmental conservation, for much of the 20th century, was dominated by this land preservation ethos. And many of the world’s “natural” parks and monuments have developed into hotspots for biodiversity despite, or because of, their artificial origins. However, by the 1960s it was becoming obvious, thanks to the work of Rachel Carson and others,11 that ecological degradation outside of these protected areas was accelerating through post-war industrialisation, particularly in agriculture. Radicalism infected parts of the ecology movement during the 1960s and early 1970s—inspired by images of Agent Orange defoliant use by the US during the Vietnam War and harrowing scenes of industrial whaling. Whether fueled by these events or the countervailing tendency of neoMalthusianism and “Population Bomb” rhetoric, the 1970s and 1980s witnessed a remarkable growth in environmental awareness and produced a consensus of concern over biodiversity loss and associated degradation.12

By the 1990s, at the close of the Cold War, there was much optimism within mainstream environmentalism that humanity would finally cooperate and coordinate its efforts to address global environmental problems. Consequently, many of the outcomes of the 1992 Rio “Earth” Summit, such as the concept of “sustainable development” and the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), were framed in a positive light despite critical voices that warned that the agenda at Rio ’92 was being shaped by Western hegemony and that vital issues of corporate power were being sidelined.13 Indeed, by the time of the Rio+10 Summit in Johannesburg, the atmosphere had turned sour. Ten years of neoliberal reforms across the Third World had seen living conditions stagnate or decline in what became known as the “Lost Decade” for development. On the ecological front, the empowerment of multinational corporations and of a growing Third World capitalist class gave rise to increased biodiversity loss as rainforests and other ecosystems were replaced by cash crops and landless peasants were forced onto the ecological margins or into urban slums.14 The 1990s witnessed a concentration of global power in the hands of Western governments, particularly the US, extending their influence over the Bretton Woods Institutions (International Monetary Fund, World Bank and World Trade Organisation) and undermining any alternatives to neoliberal economic reforms (by implementing Structural Adjustment Programmes) as part of the so-called Washington Consensus.

After a decade of frustration with neoliberal globalisation, many environmental activist groups and conservation NGOs began voicing their concerns over the ecological impact of the growing material and power discrepancies between the wealthy minority and the poorest sections of global society. Between 1999 and 2001 environmental activists and NGOs played an important role in the global anti-capitalist movement that emerged to challenge the neoliberal agenda of “globalisation” at several high-powered international meetings (Seattle WTO in 1999, Genoa G8 in 2001). Even large mainstream conservation NGOs such as WWF were caught up in the anti-capitalist mood at the turn of the century—publishing radical critiques of biodiversity loss that looked explicitly at the interactions between poverty and ecology.15

But the first decade of the 21st century was not dominated by anti-capitalism or its environmental possibilities. Instead, 9/11, Western wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, and the so-called War on Terror defined all major agendas. Simultaneously, environmentalism was rocked back on its heels by strong post-Seattle criticisms of NGOs within Western politics and across the business press.16 Indeed, the US proved so bullish in its foreign policy during this decade that it barely even acknowledged the 2002 Rio+10 Summit in Johannesburg, arguing that potentially excessive criticism of corporations by environmental NGOs made the summit irrelevant.

Between 2002 and 2012 (when the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development returned to Brazil for “Rio+20”) the political direction of mainstream environmental conservation was thrown into sharp reverse. At Rio+20 concepts such as natural capital were controversially promoted as “Green Economy” initiatives despite opposition from many activists and Third World delegates.17 Environmental NGOs—disciplined by state violence at Seattle and Genoa and increasingly entangled with neoliberal government agendas through the development of professional lobbying—appear to have been finally caught up in the trawl net of neoliberal ideology.

Since the 1970s, in a world where field experience pointed to an unfolding biodiversity crisis, conservationists (knowingly or otherwise) had been wrestling with strategies to preserve species and ecosystems in the face of a growing capitalist onslaught of commodification and profiteering. A desperate sense of urgency, combined with the political difficulties of confronting capitalism, had left many activists and NGOs in a state of paralysis by the time of the 2008 global economic downturn. The sudden implementation of global austerity, combined with calls to loosen environmental regulations, drove a gradual breakdown of the Rio ’92 consensus over sustainable development and the CBD. In attempting to maintain political relevance and access to private sector funding many conservationists became increasingly attracted to a new environmental lexicon that was being developed by the United Nations and other international bodies such as the World Bank. Within the influential Millennium Ecosystems Assessment (MEA) report,18 and the work of The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB) project,19 novel environmental metaphors were developed.20 Ecology and biodiversity, and the functions that flowed from them, were increasingly described as “ecosystem services” and markets in these being worked up as Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES). Uncritical and enthusiastic adoption of this language opened the door to an overarching neoliberal “solution” to species loss, with its emphasis on financialisation and the market—natural capital.21

The economic ancestry of natural capital

One of the world’s leading advocates for natural capital is Professor Dieter Helm, Fellow in Economics at New College Oxford and Chair of the UK’s Natural Capital Committee. Helm’s arguments for natural capital follow quite standard lines of neoclassical supply and demand economics:

For much of the conventional economy, prices and costs are accepted as the way to allocate resources. Markets are the social institutions through which demand and supply are brought together, and equilibrium is found where prices and quantities match people’s willingness to pay with companies’ willingness to produce. Changes in demand and supply work themselves out through markets… Markets are all about the allocation of scarce resources… Humans impact on almost all of nature now and, where there is no price, and hence no cost to the users of these natural resources, there is no incentive to conserve them.22

In this context environmental destruction is framed as a product of economic inefficiency. Many converts to NC—responding to the staggering scale of the biodiversity crisis, and a cynicism or disbelief in the potential for social movements to win change—agree with Helm on this.23 According to the RSPB:

Our economic system continues to fail to reflect the importance of nature in decisions that affect it. This long-term failure is at the heart of the over-exploitation of and under-investment in nature that has driven so much of the destruction of the natural world—a loss for both people and nature.

A Natural Capital approach sets out a framework that can address this failure, by better reflecting the values of nature during decision-making. If widely adopted, it could deliver huge benefits for nature and people.24

The most extreme supporters of NC blend this neoclassical analysis with a neoliberal argument that environmental regulations are both ineffective and undesirable acts of market distortion. They advocate the establishment of mechanisms to enhance Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES) and biodiversity offsetting. It is no small coincidence that these arguments are being made at this time—with land and resources facing privatisation through austerity.

Moderate advocates of natural capital are careful to qualify their enthusiasm for financialisation with a demand that biodiversity is also valued for its “intrinsic” worth. While arguing for a need to consider moral and ethical elements of nature conservation, they propose methods such as natural capital accounting as a monitoring tool that can objectively audit the impact of society—positive or negative—on biodiversity and nature. Given the recently revealed history of accounting trickery and outright fraud associated with finance under neoliberalism, this search for “objectivity” seems naïve if not counterproductive.

(Un)natural capital

Raymond Williams, in his discussion of human-nature relationships, argued that “It will be ironic if one of the last forms of the separation between abstracted Man and abstracted Nature is an intellectual separation between economics and ecology. It will be a sign that we are beginning to think in some necessary ways when we can conceive these becoming, as they ought to become, a single discipline”.25 Many of its advocates conclude that NC represents a significant step towards this disciplinary unity—one whereby nature can be integrated with economics through a calculation of its monetary value so that the full costs of exploitation are revealed, and market failure and externalities are ameliorated. Indeed, it is important to note that a strong environmental ethic lies firmly at the heart of NC. In many ways the development of the concept is implicit acknowledgement of the fact that humanity and nature are closely interrelated but that capitalism does not recognise the roles and functions of living nature within its social metabolism (thus widening the “metabolic rift” highlighted so well by John Bellamy Foster and others). In locating the source of the environmental crisis with the failure of the capitalist system, NC is an improvement on many of the historical responses to biodiversity loss that have sought to isolate humans from nature through elitist exclusion. Likewise, the narrative of “ecosystem services” that has become closely connected with NC contains ecological truths regarding our interrelationship with nature. There are ecological approaches to societal problems that could “save” money and enhance livelihoods. For example, protection and restoration of sub-tropical habitats such as mangrove forests would protect coastal settlements from flooding and maintain vital nursing grounds for tropical fisheries.

But the difficulty remains that various arms of capitalist industry have been, and are being, developed to exploit the self-made environmental problems of the system—most agribusiness operations are geared towards replacing natural ecology with artificial fertilisers and pesticides—and that these operate on shorter business cycles and vastly greater rates of profit than the “ecosystem services” that are derived from biodiversity or nature.

Although NC appears as a sophisticated, rigorous and holistic attempt to marry ecology with economics, “intellectual separation between economics and ecology” is in reality exactly what the approach entails. In place of critical analysis based on holistic socio-ecology, NC throws a net of economic simplicity and ideology over nature in its entirety. It seeks to identify the “true costs” of environmental degradation and conservation but its advocates have restricted themselves to an appallingly narrow spectrum of economic theory in order to demonstrate nature’s worth.

The branches of economics that have been utilised—an unholy alliance of neoclassical and neoliberal doctrines—are so deeply enmeshed with bourgeois perspectives on economic respectability that NC advocates have somehow failed to notice that these are the very same schools of economics that have driven the biodiversity crisis while normalising our collective alienation from nature—the fundamental driving force behind the loss of biodiversity and associated human cultural diversity.

The outcomes of NC are therefore the exact opposite of what it proposes. Appealing to market capitalism, its corporations and politicians, to value biodiversity through money is akin to asking the fox to look after the henhouse. The situation is made even more perilous by the way in which NC has moved from being a technical method of environmental economics engaging in stocks and flows analysis to become a substitute for the concept of “nature” itself.26

If the development of NC is considered from the broader economic perspective that Williams subscribed to—one embedded in historical materialism—then three possible interpretations of this unfortunate turn in environmental history can be explored: natural capital as fictitious commodity; as primitive accumulation and as disaster capitalism.

Natural capital as “fictitious commodity”

NC represents an explicit attempt to assign economic value to biodiversity and ecosystems—entities that have failed to appear on the balance sheets of capitalism because they are viewed as market externalities or public (free) goods. But there remains a substantial problem with a valuation exercise that compares or meshes the value of currently free services with those generated, and therefore already transformed into commodities, by human labour.

The chief problem is derived from the competitive market atmosphere into which ecosystem valuation is placed. Typically, for example, TEEB calculates that the total economic value of the Charles River Basin in Massachusetts is the equivalent of $95.5 million per annum (see table 1).27

Table 1: The economic value of the Charles River Basin

|

Economic benefit |

Economic value per year (converted to US dollars) |

|

Flood damage prevention |

39,986,788 |

|

Amenity value of living close to the wetland |

216,463 |

|

Pollution reduction |

24,634,150 |

|

Recreation value: small game hunting, waterfowl hunting |

23,771,954 |

|

Recreation value: trout fishing, warm water fishing |

6,877,696 |

|

Total |

95,487,051 |

This value is calculated from, “the benefits derived from these wetlands [including] flood control, amenity values, pollution reduction, water supply and recreational values”.28 Since a proportion of this value is calculated from market prices (the housing market element of “amenity value of living close to the wetland”) then the wetlands’ total value can rise and fall in line with non-ecological factors. A leisure or tourism contribution to ecosystem valuation is similarly problematic since it depends ultimately on the wetland’s ability to compete with other leisure or tourist attractions, as well as an assumption that workers can maintain leisure expenditure despite booms and busts within the wider economy. In Costa Rica—the country often portrayed as the model for NC and PES—some ecologists have gone so far as to argue that rainforests should effectively be seen as farms for ecotourism and that the number of tourists visiting a rainforest reserve (and their associated tourist dollars) should be seen as the rainforest’s crop!

A certain proportion of ecosystem valuation is, by implication, derived from within the existing capitalist system—for the Charles River Basin wetlands, roughly a third of their economic value is derived from existing fluctuating monetary cycles (the dollars spent on amenity and leisure). The remaining values that are applied relate to the ability of ecosystems to supply a monetary-equivalent service to humanity (flood damage prevention and pollution reduction). But these figures are similar to “fictitious capital”—“money that is thrown into circulation as capital without any material basis in commodities or productive activity”29—because they are applied as arbitrary values against an anthropogenic equivalent that would necessarily be derived through labour. If the value of an ecological function is only compared to how much it would cost humans to adopt technological measures were we to undertake the same “service”, then a Marxist perspective shows how this comparison makes only limited sense. The latter would be determined by the quantity of human labour, not by any non-human ecological quality.

Further, where this comparison has played out on the ground the results have been unpredictable. Pollination is a much-lauded ecosystem service that is rightly highlighted by environmentalists as a deep and growing challenge as industrial pesticides have decimated species of bees and other invertebrates across the world. Hanyuan County, in China’s Sichuan province, is noted for its fruit production—in particular its pear orchards. Over the last decade the region has suffered a pollination crisis as bee populations have crashed through historic use of pesticides. In the face of this crisis, farmers turned to human labour and much of the annual crop has now become dependent on pollination by hand—a process whereby pollen is dusted onto blossom by labourers. In the early phase of this crisis, although beehives could be rented to achieve the same outcome, farmers used workers to replace bees because labour costs were low and productivity increased as the human eye proved to be more effective. The crisis has recently returned as poor rural workers have migrated towards urban areas under industrialisation. As this example hints, once valued and embedded within the capitalist system, ecosystem services and its NC basis could be outcompeted by technological advances or other human attributes. In this regard, the possibilities of overvaluation and undervaluation through the desires and whims of speculative capitalist investors is also very real.

NC can also be described as a form of fictitious capital because its concern with realising monetary value for ecosystems through PES is effectively a form of ground rent. David Harvey argues that rent itself is a fictitious commodity, and that Karl Marx saw such as a sign of capitalism’s insanity.30

Natural capital as “primitive accumulation”

Capitalism’s historic ability to secure value from without was described by both Marx and Rosa Luxemburg as “primitive accumulation”. While the privatisation and direct appropriation of communal resources such as land played a historical role in early capitalist expansion, certain aspects of this strategy appear to function today in the guise of “accumulation by dispossession”.31 In the Third World, dispossession of peasants’ landholdings to service the needs of international commodity markets in “cash crops” has accelerated under neoliberalism since the 1970s—a trend continuous with colonial and post-colonial patterns of land use.32

NC appears to enhance this characteristic through its growing link to international agreements and legal structures that will permit the development of property rights over ecological entities and functions. The transformation of public goods into property rights has the potential further to alienate humanity from its ecological base. In practice, this could arise through the impact of enclosure of formerly open resources through legislation or through illegal or discounted land grabbing.33 As previously mentioned, such acts have already carried controversial implications within biodiversity conservation where land has been enclosed for nature reserves by colonial powers.

The intention appears benign—formal ownership of an ecosystem by its human users and managers should facilitate payment for its maintenance in line with the value derived from its local, regional and global ecological services. However, the introduction of ownership rights can subject these beneficiaries to new pressures. For example, once an ecosystem is entered into the cash nexus, what is to stop other wealthier interests from buying up resources and ecological rights? What happens if the function of an ecosystem becomes dominated by the needs of one interest group associated with a particular ecosystem service over another? Fixed ownership rights are also difficult to predict over time because of the dynamism inherent within ecology: How can ecological dynamism operate where the rationale for conservation of an ecosystem or species may be fixed to a particular marketable outcome? What happens to market value when an ecosystem changes its characteristic from within? These questions are generally avoided by NC environmentalists. But the issues raised do hint at the potential discrepancies between ecological functions and valuation imperatives under capitalism, and the dangers of extending the frontier of capitalist accumulation across living nature itself.

Natural capital as “disaster capitalism”

The rationale for NC is derived from the biodiversity crisis. This, in turn, has its historic roots in the evolution of human societies. But the greatest acceleration in environmental degradation and associated biodiversity loss has occurred over the last 300 years through the development of capitalism. Within this period, the last four decades have witnessed the most extensive rates of degradation as capitalism has forced its way into every nation state and an increasing share of human activities. The growing dominance of capitalism over human affairs has given rise to a situation where capitalist solutions are increasingly offered to those crises that have arisen from the system itself. In its most extreme responses, “disaster capitalism” has even used natural disasters and wars to further its neoliberal penetration into regions and nation states.34

The circular logic of capitalist solutions to capitalist crises is now so commonplace that many formerly radical environmentalists have given up on criticising the system in order to explore options for how environmental problems can be addressed by capitalist measures.35 The tone of TEEB itself is almost incredulous when it comes to the objective concerns of conservation to protect biodiversity from capitalist development: “Even today, more political emphasis is placed on protecting and isolating ecosystems from economic development and commodity markets, than on redefining and regulating the latter”.36

While NC carries the stated aim of protecting biodiversity, the tendency for capitalism to seek to profit from its own crises means that it could equally operate as a truly grandiose version of “disaster capitalism”—a neoliberal response to the Anthropocene—that generates profit opportunities from a crisis of geological proportions.

The tragedy of natural capital

All three of these radical interpretations of natural capital are connected by neoliberal conservationists’ acceptance of markets and private property relations. In particular, NC proponents display enormous faith in privatisation as a solution to the degradation of environmental commons. This ideological position has its own creation myth in the form of Garrett Hardin’s “Tragedy of the Commons”—principally a Malthusian argument but one that has been produced regularly over the last half century to argue against any communal or socialist solutions to environmental problems.37

In Hardin’s own words:

The [tragedy] develops in this way. Picture a pasture open to all. It is to be expected that each herdsman will try to keep as many cattle as possible on the commons. Such an arrangement may work reasonably satisfactorily for centuries because tribal wars, poaching and disease keep the numbers of both man and beast well below the carrying capacity of the land… Once social stability becomes a reality…the inherent logic of the commons remorselessly generates tragedy…each man [becomes] locked into a system that compels him to increase his herd without limit—in a world that is limited. Ruin is the destination toward which all men rush, each pursuing his own best interest in a society that believes in the freedom of the commons. Freedom in a commons brings ruin to all.38

Hardin targets the need to control the “freedom to breed” in particular, but his theory (which has virtually no ascertainable accuracy because “commons” have been historically managed and sustained through cultural practices and are never left “open” in the sense that Hardin promotes) is more often used to justify the need to privatise commons to realise their value and thereby to conserve them. This embeds them within a market system (in line with neoclassical economic views).39

Helm and virtually all the natural capital converts that I have met in conservation use Hardin’s work as their starting point and justification. On that basis alone the assumptions of NC are as borderline fraudulent as Hardin’s bourgeois-friendly theory. Alas, the economists and ecologists now engaged with NC have been allowed to take this pseudoscience to the next level of academic and disciplinary respectability despite the efforts of Marxist critics such as Paul Burkett.40

Towards a socialist response

The uncritical promotion of NC by environmental conservationists is a tactic of profound self-defeat. By encouraging the financialisation of nature, these environmentalists are actively extending the frontier of capitalist commodification across the living earth. Whether their motivations are derived from well-meaning pragmatism or neoliberal ideology, they will find that the crudeness of their efforts will backfire. In place of greater value-realisation for Earth’s wonderful biodiversity, a crude lexicon of dumbed-down ecosystem services will come to the fore. Pro-development initiatives such as biodiversity offsetting41 are already riding on the coat-tails of this commodification. And the much-hyped “new innovative markets” will merely promote Payments for Ecosystem Services, further enriching wealthy landowners and encouraging land grabbing and dispossession. Already, a new group of technocratic ecologists is emerging to promote and exploit the pseudoscience of NC, offering enhanced monetary and political power for large NGOs and ecological consultancies, and a corresponding disenfranchisement of the public body and vulnerable groups such as small farmers and indigenous people.

Natural capital is potentially dangerous and its advocates must be vigorously challenged, despite the fact that they have normalised the concept within international politics and environmental discourse. At best, the concept is a hopelessly ineffective means to reverse the sixth extinction because it represents little more than another capitalist solution to a capitalist crisis. At worst, it provides the basis for commodifying, privatising and trading in living nature—developing new markets based on our current system of speculation and profit that will corrupt and distort ecology for short-term aims—leading to further biodiversity loss.

In place of capitulation to commodification, environmentalists would better serve the interests of biodiversity if they subscribed to Harvey’s observation: “We have loaded upon nature, often without knowing it, in our science as in our poetry, much of the alternative desire for value to that implied by money”.42 The struggle for alternative non-monetary, valuation is a central theme within socialism and other anti-capitalist traditions. It is an expression of resistance against the barbarism unleashed by capitalist valuation in all areas of human affairs, from ecology to education, from science to the arts. Appreciation of the need to fight for environmental quality over the quantitative world of the cash nexus helps us to consider our historic function and relevance as socialist ecologists. In those respects, we must fight for biodiversity today with a view to enhancing its recovery tomorrow. Whether the future is bound by ongoing and decaying capitalism, or is thrown open by meaningful revolution, we can operate today in the interests of all life on Earth once we accept and advocate certain radical conclusions.

First, that capitalism is ecologically dysfunctional and inherently destructive of biodiversity. Second, that dominant, neoliberal misanthropic explanations of the biodiversity crisis are fatalistic and cynical regarding humanity’s historical and future interrelationship with biodiversity. And that the solutions (natural capital, neo-Malthusianism, the “tragedy of the commons”, “clearance rewilding”, the privatisation of nature reserves) flowing from these positions are also largely ideological and pro-capital.

Biodiversity conservation under prevailing capitalism is a “spaces of hope” project. Through various tools within the reformist armoury, we need to save what we can with meagre resources in the limited time available to us. These tools will also provide vital ecological lessons for the historically viable mode of society that will be derived through socialism. Some tools are socially and ecologically imperfect and need to be improved because of their association with elitism (nature reserves and national parks). Others require direct community activism across diverse united fronts that can cross class boundaries and seek to utilise complex planning and legal frameworks (resisting developments like fracking, or motorway road schemes). Some are currently small in scale but have enormous potential if they could be scaled-up under a different mode of social reproduction (organic agriculture and agroecology). Some are emergency measures that are fundamentally unappealing but sadly necessary (rare species breeding programmes, seed banks and zoological gardens). Others are largely verbal and prone to ambiguity or abuse but can be useful campaigning tools for holding power to some account (“sustainable development” legislation).

Whatever tools we use, we are compelled to act today in favour of biodiversity and its positive human associations in very distressing circumstances. But by maintaining radical critique while deploying the tools to hand, and acting in solidarity with groups and classes that are closely entwined with biodiversity, we can also generate ecological optimism for the Anthropocene on the reasonable Marxist grounds that the seeds of future society are sown in the present.

Ian Rappel is a conservation ecologist and member of the SWP. He is also a member of the Beyond Extinction Economics (BEE) network.

Notes

1 I am grateful for comments and feedback on this article from Bram Büscher, Alex Callinicos, Martin Empson, Camilla Royle, Sian Sullivan and Colin Tudge.

2 Rappel, 2015.

3 The World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF)—the self-proclaimed “world’s leading conservation organisation”—has more than 1 million members in the United States and 5 million globally. The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) in the UK has over 1 million members. Greenpeace claims 130,000 supporters in the UK and 2.8 million around the world. In early 2018 the Labour Party had 552,000 members, the Conservatives 124,000, Scottish National Party (SNP) had 118,000, Liberal Democrats 101,000, Green Party 41,000, UK Independence Party (UKIP) 21,000 and Plaid Cymru 8,000 members.

4 Churchill, 2014.

5 Hunter, 2004.

6 Sullivan, 2017, p66.

7 RSPB, 2017, p10.

8 Spowers, 2002.

9 Adams, 2004; Adams and McShane, 1992; Dowie, 2009.

10 Weiner, 1988.

11 Carson, 2000 [1962].

12 Ehrlich, 1968; Cherfas, 1989.

13 Middleton, O’Keefe and Moyo, 1993; Treece, 1992.

14 Rappel and Thomas, 1998.

15 See Wood, Steadman-Edwards and Mang, 2000. WWF sent a delegation to the demonstrations at the Genoa G8 summit.

16 Economist, 2000.

17 Empson, 2012.

19 TEEB, 2010; Ninan, 2009.

20 Many of these concepts have their roots in the early discussions on “green capitalism” that were circulating on the fringes of mainstream environmentalism during the late 1980s.

21 An excellent critical overview and assessment of neoliberal conservation can be found in Büscher, Dressler and Fletcher, 2014. Sian Sullivan’s pamphlet for the Third World Network (Sullivan, 2012) also gives a useful introduction to the evolution of natural capital and nature financialisation.

22 Helm, 2016, p117.

23 I am grateful for Martin Empson’s input on this point. Tony Juniper, formerly Executive Director for Friends of the Earth UK, is one of the highest profile advocates of NC, and has declared his new role at WWF to be one of Natural Capital advocacy—Juniper, 2013; Juniper, 2015.

24 RSPB, 2017.

25 Williams, 2005, p84.

26 I am grateful to Professor Sian Sullivan at Bath Spa University for this observation.

27 TEEB, 2010, p383.

28 TEEB, 2010, p383.

29 Harvey, 2006, p95.

30 Harvey, 2006.

31 Harvey, 2003; Harman, 2008; Glassman, 2007; Ashman and Callinicos, 2006.

32 Harman, 2008; Rappel and Thomas, 1998.

33 Peluso, 2007; Pearce, 2012.

34 Klein, 2008.

35 See or examples: Porritt, 2005; Lynas, 2011; Juniper, 2013.

36 TEEB, 2010, p155 (emphasis added).

37 Hardin, 1976 [1968]. Hardin’s work, like that of the Reverend Thomas Robert Malthus, could be quite accurately described as a libel against humanity (to borrow Marx and Engels’s phrase). However, unlike Malthus’s Essay on the Principle of Population, Hardin’s work has no redeeming features. The Essay was at least extremely influential in the development of Charles Darwin’s and Alfred Russell Wallace’s theory of natural selection. It is a source of some historical solace to think that Malthus’s work went on to help establish one of the most important pillars of philosophical materialism (if only because he certainly would not have wanted that as a legacy!).

38 Hardin, 1976 [1968], pp235-236.

39 For excellent critiques and counter-blasts to Hardin’s lazy theory I would recommend reading Ian Angus’s 2008 essay for Monthly Review Online (Angus, 2008) and the book The Tragedy of the Commodity by Stefano B Longo, Rebecca Clausen and Brett Clark, 2015.

40 Burkett, 2006.

41 “Biodiversity offsetting” is the means by which capitalist developers, states and consultant ecologists assign scores for ecological damage within an agreed matrix of habitat type, species presence and quality. These scores are then given a monetary value with the aim of creating equivalent habitats elsewhere once the area under development has been destroyed. The concept is, unsurprisingly, mired in controversy.

42 Harvey, 2016, p174.

References