In the 1990s and beyond, the concept of globalisation dominated the business press and academic economics.1 Globalisation became a new orthodoxy and was declared to be sweeping aside state economic intervention of various sorts (planning, nationalised industry and welfare spending) as governments acknowledged their powerlessness to rein in transnational capital or global financial markets. New words and phrases appeared: “footloose” capital with limited connections to any state roamed an increasingly “borderless” world; in this “post-national” era, the ruling classes of the major economies had become increasingly “cosmopolitan”. Those Marxists who challenged the orthodoxy were in danger of appearing out of touch and wedded to the familiarity of a national frame of reference. Meanwhile, as central banks became independent of governments, a new breed of high-tech business leaders expanded from the United States into the Chinese market, even if that meant strengthening “communist” China’s state-directed economy. In 2016, of Silicon Valley’s top 20 IT executives, only Larry Ellison supported Donald Trump’s presidential campaign.

However, something is changing. The Global Financial Crisis of 2008 exposed the fragility of markets and compelled states to take steps to restore stability, including by bailing out banks and orchestrating quantitative easing by nominally independent central banks. By 2012, the business weekly the Economist—long-time bastion of free market orthodoxy—warned of the “rise of state capitalism”, suggesting that it may be “the emerging world’s new model”.2 This trend was reinforced by the response to the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020. Today, the aura of cosmopolitanism around the “tech bros” has evaporated and most support Trump’s Make America Great Again (MAGA) project.

State economic activity has been rehabilitated more widely. A century ago, it was often associated with the catch-up efforts of late developers and the protection of weaker economies. Half a century ago, the newly independent countries of the global south mobilised state power to compensate for weak domestic capitalist classes. Today, state actions in key high-tech sectors pursued in what Tobias ten Brink calls China’s “state-permeated capitalism” are mirrored in the major Western countries, the largest sovereign wealth funds are those of some of the world’s richest societies, and economic statecraft in the form of tariffs, inducements to capital and expansion of foreign markets is being aggressively applied by the world’s most powerful state, the US.3

This article analyses contemporary trends in the relationship between states and capital. Firstly, I will briefly outline the relationship between states and capital in Marxist theory; secondly, I will discuss the tendency towards state capitalism that developed across the advanced capitalist countries from the end of the 19th century. Thirdly, I will explain why the Stalinist Soviet Union should be characterised as bureaucratic state capitalism—something that is central to the classical Marxist tradition in which this journal stands. The Soviet Union, the most developed form of state capitalism, collapsed in 1989-91, after which it and its satellites in Eastern Europe were radically restructured as part of a more general re-shaping of the state’s relations with capital under neoliberal globalisation. I will analyse some these processes in the fourth part. Many authors writing in this journal, or associated with it, have demonstrated that claims about the “retreat” of the state in the neoliberal era, which followed the state capitalist era from the end of the 1970s, are over-stated and over-simplified.4 Although there was no fundamental state retreat, the re-shaping of state-capital relations was real. Today, a re-emergence of important aspects of earlier versions of state capitalism, particularly in industrial policy, is equally real. The significance of this re-emergence lies not in its corroboration of the general theoretical approach of this journal, but in its demonstration that global capitalism has entered a more conflictual and unstable era in which inter-imperialist rivalry is deepening. This threatens the very future of our planet.

State and capital in Marxist theory

States played a vital role at the birth of capitalism as they sought, in Karl Marx’s words, to “hasten, hothouse fashion” the transition from feudalism to capitalism.5The British state promoted primitive capital accumulation by protecting, and effectively participating in, the bloody plunder of less developed parts of the world. Bourgeois ideology presents markets as natural but, as the economic historian Karl Polanyi argued, “there was nothing natural about laissez-faire; free markets could never have come into being merely by allowing things to take their course…laissez-faire was enforced by the state”.6 So contrary was the new market society to existing social behaviour that its introduction, “far from doing away with the need for control, regulation, and intervention, enormously increased their range”.7 This was especially true of the labour market, which was forcibly created via a series of draconian measures, including land clearances, the prohibition of vagabondage, and the establishment of the work-house system. Marx concluded that the state plays an essential role, which cannot be performed by any other body, in setting “the conditions for the existence of capital”.8

Beyond protection of property rights, these conditions include provision of physical infrastructures (transport, power, water, communications). However, since, as Marx argued, capital is not a thing but a “definite social production relation”, a relation between dead and living labour, these conditions for the existence of capital primarily concern the enforcement of social relations, attitudes and behaviours conducive to capitalism. These include state measures to create an educated and trained workforce, to maintain workers’ health, and to reproduce labour-power (and society more generally). The reproduction of labour-power takes place mainly in the family, which simultaneously reduces the cost to capital and perpetuates traditional gender roles, but although it is largely privatised, it is regulated and supported by states. Capitalists and their ideologues frequently bridle against state encroachment on their property rights, but without state power (funded primarily by surplus-value produced in national economies), the effective exercise of property rights and the reproduction of the entire system would be jeopardised. Capitalism in all its forms has always depended on state actions, such that states and capitals have always operated within a relationship of what Chris Harman called “structural interdependence”.9 The precise balance between the two is not fixed, however, and in different periods their relative importance changes.

An era of state capitalism

The phenomenon of state capitalism is rooted in the development of capitalism itself. Rosa Luxemburg captured the emerging statisation of capitalism at the end of the 1890s:

[C]apitalist development modifies essentially the nature of the state, widening its sphere of action, constantly imposing on it new functions…making more and more necessary its intervention and control in society. In this sense capitalist development prepares little by little the future fusion of the state and society.10

The increasing role of the state had both national and international dimensions. Capitalist industrialisation in the advanced countries produced a new and rapidly expanding working class—according to Marx, the “grave-diggers” of capitalism—which was concentrated in urban areas, increasingly literate and organised in trade unions and socialist parties.11 From the last decades of the 19th century, these new labour movements demanded that states enact social reform and protective legislation. Polanyi explained increasing state regulation as the second element of a “double movement”, a reaction to marketisation (the first element) that would have “annihilated” society “for protective countermoves which blunted the action of this self-destructive mechanism”.12 Where state power had previously ensured that society was run “as an adjunct to the market”, those same states now engaged in processes to re-embed the economy in wider social relations and to provide more extensive infrastructures for the reproduction of labour-power.13 Across Europe, and under a variety of political regimes, market-limiting welfare legislation covering workplaces, public health and social insurance now appeared. The extent and pace of social reform were influenced by levels of class struggle, but states faced pressure from above as well as from below. As Luxemburg highlighted, capital’s requirement for healthy and educated workers meant that “labour legislation is enacted as much in the immediate interest of the capitalist class as in the interest of society in general”.14

International competition also demanded that states intervene more systematically in processes of capitalist production and social reproduction: as Ellen Wood put it, capitalism is a “global system organised nationally”.15 However, in organising the national component of global capitalism, states are not passive bearers of global pressures and simply translate global imperatives into a national framework. Capitalism had transformed the world’s societies and states, but states now shaped particular national forms of capitalism.16

In the early years of the 20th century, the Bolshevik Nikolai Bukharin developed the Marxist analysis of the international dimension of increased state roles. His 1917 book, Imperialism and World Economy, took the global capitalist economy as his point of departure. He wrote that “there grows an extremely flexible economic structure of world capitalism, all parts of which are mutually inter-dependent. The slightest change in one part is immediately reflected in all”.17 This was not a smooth conflict-free process. Rather, interdependence intensified international competition: late-developers such as Germany, Russia and Japan faced up to Britain’s global leadership and imperial expansion by pursuing state-orchestrated social and economic change to facilitate rapid capital accumulation. Measures included the establishment of state-owned savings banks to concentrate savings, huge infrastructural developments and programmes of expanded technical education provision.

Capitalist internationalisation, driven by the systemic imperative of competitive accumulation (and expressed in the emergence of multinational firms, increasing overseas trade and investment) thus provoked “a reverse tendency towards the nationalisation of capitalist interests”.18 For Bukharin, this generated pressure towards state capitalism—combining both increased state activity in the economy and the increasing clustering of big capital around home states—that were called upon for support in the competitive struggle for colonies, market access, sources of raw materials and investment opportunities overseas. Bukharin may have over-stated aspects of his thesis (including that national economies would become so statised that they would develop into a single combined enterprise), but he grasped the essential character of global capitalism in the first half or more of the 20th century. What developed was an extended epoch of state capitalism and, as economic competition dovetailed with inter-state rivalries, military competition and conflict.

States mediated and modified global pressures in the context of existing social structures, cultures, institutional arrangements and political conditions. As a consequence, national capitalisms retain their peculiarities, yet, as David Coates put it, the surface impression of a world that is “irreducibly pluralistic and complex” masks “an underlying structuring logic…tied to the uneven development over time of capitalism as a world system”.19 It is the structuring logic of global competitive accumulation, and the military rivalry that is one of its forms, that provide the essential framework for understanding the nature of the Soviet Union after the revolutionary transformation of 1917 had been isolated and quarantined by the advanced capitalist powers.

Bureaucratic state capitalism in Soviet Russia

Formulaic versions of Marxism identify capitalism with the economic sphere, identifying all other spheres of human activity as “not-capitalism”, including the actions of states. They erect a sharp distinction between politics and economics and thereby deny that states and capitals are interdependent, differentiated forms of ruling-class power and both structured by the same capitalist logic. In contrast, the Marxist geographer David Harvey argues that the concept of mode of production does not simply refer to the economy, but it refers to:

the whole gamut of production, exchange, distribution and consumption relations as well as to the institutional, juridical and administrative arrangements, political organisation and state apparatus, ideology and characteristic forms of social (class) reproduction. In this vein we can compare the “capitalist”, “feudal”, “Asiatic”, etc, modes of production.20

Harvey’s approach is broadly shared by the tradition associated with this journal. The foundational document of this tradition, Tony Cliff’s State Capitalism in Russia, argues that the consolidation of the Stalinist Soviet bureaucracy in 1928 and the first five-year plan represented a counter-revolution, which led to the establishment of what Cliff analysed as bureaucratic state capitalism under the dominance of a new ruling class. The source of its power lay in its control over the Soviet state and ownership (understood as effective control) of nationalised property. Together, these enabled the state capitalist ruling class to control the social surplus that flowed from the exploitation of workers. Politics and economics were institutionally differentiated but essentially combined.

The essential unity of the two aspects of Soviet ruling-class power was highlighted in Michal Reiman’s important book The Birth of Stalinism, which drew on a chance discovery of an archive of Soviet historical materials in West Germany’s foreign ministry in 1969. Reiman showed how the Stalinist bureaucracy’s possession of the police and judicial apparatus gave it a monopoly over the means of coercion and of ideological production that enabled it to increasingly impose its own interests on society in the late 1920s, particularly after the elaboration of the first five-year plan. The astonishing list of repressive measures taken in early 1929 destroyed the last vestiges of the power of the working class, which had been the chief gain of the 1917 revolution. One-man management was instituted in place of the troika system under which the unions, independent to a degree until 1928, exercised some control over management decisions; management was granted increased rights to discipline and fire workers; courts were prohibited from hearing workers’ complaints over discipline and dismissals; and the unions henceforth refused to defend their members in the courts. At the same time, Sunday was abolished as a day of rest, rationing was introduced, and a dramatic extension of the piece-work system, which acted as a powerful atomising force on the working class, was initiated. By 1932, 68 percent of workers were paid on piece-rates.

The rise of bureaucratic state capitalism extinguished the last embers of workers’ power in industry and reversed the revolutionary changes that had provided a basis for women’s emancipation and the transformation of traditional gender roles and relations. The measures to socialise much of the burden of housework and child-care introduced immediately after the revolution (including work-place laundries and canteens) fell victim to the reassertion under Stalin of the centrality of the private family in the reproduction of labour-power. After 1945, the Soviet model was imposed on Eastern Europe and was replicated in China after the 1949 revolution.

Although the picture was not uniform, the loss of male workers during the Second World War increased the demand for women’s labour. Their formal economic participation was generally greater than in the West and provided opportunities and benefits not widely available to Western women. This was particularly true in East Germany, Eastern Europe’s most advanced economy, where the number of male workers killed during the war was especially high. The state encouraged the upskilling of women workers, and women entered sectors traditionally dominated by men in increasing numbers, including in managerial positions. They also entered more prestigious sectors, including higher education and the sciences. In general, in the state capitalist countries, women’s experience of work—including paid maternity leave, access to childcare and crèches—improved significantly after 1945.

However, the driver of these changes was not the Stalinist system’s commitment to women’s emancipation but its need for supplies of labour. This meant that while many women saw a significant improvement in their lives, these could be precarious: subordinate to the drive to industrialise, the supply of crèches, kindergartens and canteens was never sufficient to meet women’s demand, and when growth slowed, as in Czechoslovakia in 1962-3, the government declared the abandonment of the “ideological concept of socialised housework”.21 Women continued to shoulder the “double burden” of work inside the home (including shopping, cooking, housework and child-care) and paid work outside, reinforcing their subordinate position in society. This was expressed in numerous ways, including official perception of women as a source of cheap labour and the sort of gender pay gap that is still familiar to women in the West. There was also a gendered division of labour in which women were generally marginal in decision-making and managerial positions, occupied the lowest paid jobs, performed unskilled work or worked part time (which lightens the double burden slightly but at the expense of wider advancement). Although the demand for women’s labour meant that women in the East, particularly in East Germany, worked in a wider variety of jobs than women in the West, the gender division of labour was also, as in the West, illustrated by women’s disproportionate concentration in traditional “women’s work”, including education, health and social care.22 Whatever the differences between the economies of the Eastern bloc, and whatever the claims of Stalinists, state capitalism did not represent a realisation of Marxism’s vision of women’s emancipation but a backward step compared to the years of hope immediately after 1917.

The systematic restructuring of the Soviet economy and society reflected the weakening of the working class and the Bolshevik rank and file during the civil war and war of intervention, and the related rise to power of the party-state bureaucracy in the 1920s. However, echoing Bukharin’s dialectic of internationalisation and nationalisation, Cliff emphasised that the dynamic was not simply an internal one. Stalin was acutely aware of the competitive international environment, arguing in November 1928 that “it is impossible to defend the independence of our country without a sufficient industrial base for defense… Either we acquire it or we will be wiped out”.23 He repeated his argument in 1931, telling factory managers that “we are fifty or a hundred years behind the advanced countries. We must make good this lag in ten years. Either we do it or they crush us”.24 This demanded what Reiman calls Stalinism’s “complete break with the meaning and essence of the social doctrine of socialism”.25

The roots of bureaucratic state capitalism in the specifics of the history and class structure of the Soviet Union in the decade after 1917 meant that it involved the almost complete statisation of the forces of production. This led to confusion on the international left over how to understand the Soviet Union. For many, capitalism is defined by private property, understood as legal ownership by individuals or corporations. In the context of the global system of competitive accumulation, Soviet nationalised property was private precisely because it was in the exclusive possession of the Soviet state: all non-Soviet citizens and, of course, outside the realms of ideology, almost all Soviet citizens were excluded from exercising any influence over its use.

Soviet state capitalism was the most extreme form of the general phenomenon that Bukharin identified in 1916, but across the world, statised forms of capitalism predominated until the rise of neoliberalism at the end of the 1970s. Every crisis stimulated further state measures to protect the national economy and national capital. In response to the Wall Street crash and the early years of the 1930s depression, both Britain and the US came off the Gold Standard, thereby de-linking from the direct penetration of the law of value and the subordination of their economies to international monetary movements. The Second World War saw the systematic organisation of the combatants’ national economies by states. After 1945, state capitalism was further stimulated by the extension of Soviet power into Eastern Europe, and the emulation of the Soviet model in China and elsewhere. In the West, the strength of labour movements and the East-West rivalry reinforced the competitive pressure on capital to enhance the welfare funding that in any case met its own interests in removing such spending from the responsibility of individual capitals. The nationalisation of heavy industry was commonplace. In the global south, the weakness of domestic capitalist classes reinforced the establishment of national champions as a symbol of sovereign independence in newly post-colonial states. In some parts of the global South, in Asia in particular, “developmentalist” states corralled capital behind the drive for national growth and development.

Paul Samuelson, author of the best-selling economics textbook in the 1960s, wrote that Keynesian methods of state planning and demand management had solved capitalism’s fundamental problems. Yet, over the next few years, as a crisis of profitability developed, labour and other social movements began to pose a challenge to capitalism on a scale not seen for 50 years. By the mid-1970s, capitalism was mired in the first full-blown economic crisis since the 1930s. The ultra-liberals, who had been preaching free-market ideology from the political margins since 1945, now began to exert a greater influence in ruling class circles in various Western countries, spearheaded by the US and Britain, where growth rates had been particularly anaemic. With the partial exception of Chile after Augusto Pinochet’s 1973 coup, neoliberalism never achieved a complete transformation of existing national economic systems and proceeded via pragmatic programmes of reform, particularly where it met resistance. However, by the early-1980s, neoliberalism’s promise to restore profitability and the power of capital meant that state capitalist arrangements were coming under pressure in many of the major economies.

Neoliberalism and the partial retreat of the state

As we will see below, the relationship between neoliberalism and the capitalist state is not straightforward and it has simultaneously subverted some aspects of state power (such as regulation of capital) while strengthening others (including anti-union measures). This is explained by contradictions in the nature of the postwar capitalism that neoliberalism encountered: increasingly statised in key respects (welfare and nationalised industry), yet also increasingly exposed to internationalisation (trade, overseas investment and growth of global financial markets) due to pressure from the US and the world’s largest capitals. Nevertheless, neoliberal ideologues hammered home the argument that the state is an obstacle to entrepreneurial dynamism and a source of inefficiency and slow growth. However, their chief purpose was to dismantle not the state but influence of the labour movement on state policy and to re-shape popular conceptions on the boundary between the public and the private. They fully understood that even if the state’s role was to shift from direct production to market-enabling functions, it was to be reconfigured, not dismantled. Four decades of neoliberal restructuring and globalisation have reconfigured many of the aspects of the forms of state capitalism that persisted for some 75 years in the West. In 1989-91, the Soviet-style variant collapsed. The change forced through under what was dubbed the “Washington Consensus” co-existed with more continuity.

On the change side, mainstream politicians reeled off a litany of arguments that became a decades-long common sense. A dramatic growth in trade was increasingly exposing national economies to global price comparisons and so applying pressure to reduce state taxation and spending. Public policy needed to be driven by value-for-money considerations and so had to accommodate the private sector, part of whose superior efficiency over the public sector was because private firms often reaped global economies of scale. State spending is now policed by international capital markets, global ratings agencies and international financial institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. Production by state-owned enterprises (SOEs) dwindled as a proportion of total national production and many state assets were privatised. Even in China, SOEs only account for about 30 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP), while 50 percent of banking is in private hands.

At the time, mainstream demonisation of the welfare (“nanny”) state was commonplace: as Francis Castles and his co-writers put it in The Disappearing State?, neoliberals argued that “big welfare states could not compete in increasingly globalised markets because high levels of ‘non-productive’ state spending constituted a source of economic inefficiency”.26 In their book, which was written at the height of the globalisation orthodoxy, they highlight the continuity with the earlier era, puncturing numerous myths about neoliberalism. They look at trends in state spending between 1980 and 2005, focusing on the countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Their data relies on the OECD’s Classification of the Functions of Government (COFOG) system for analysing national accounts.27 COFOG includes education, general public services (the costs of running the state and collecting taxes), defence, public order and safety, economic affairs (for example, subsidies), environmental protection, housing and welfare. The Disappearing State? largely excludes welfare, which Castles explores elsewhere, Only Chapters 1 and 2 analyse the totality of state spending including welfare. The other chapters look at specific COFOG categories. The results are striking.

Although there is no uniform pattern across the entire OECD, the data generally shows small cuts in core expenditure (tax collection) and public order spending (which in some cases rises slightly though). In line with neoliberal laissez-faire, there were significant cuts in state regulation (of product markets and the labour market) as well as industrial subsidies. Defence spending was also cut, as was spending on education.

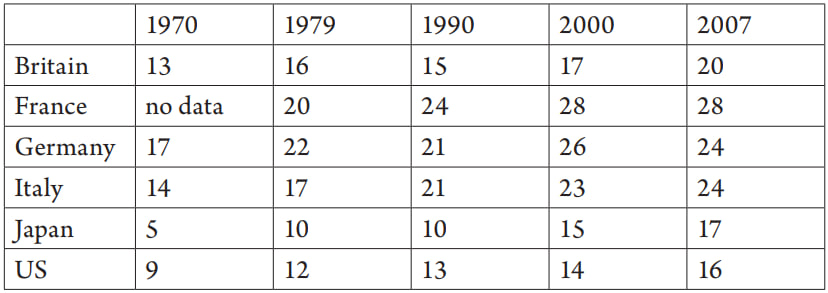

Much of this is to be expected, but what is surprising is that savings were more than used up in expanding welfare: “over the period as a whole, average increases in social expenditure outweighed aggregate cuts in core spending”.28 In the 1980-2001 period, “average OECD levels of social expenditure increased by 3.9 percent of GDP…[to 22.7 percent, while] core spending levels declined by 1.4 percent of GDP [to 22.9 percent]”.29

These figures are corroborated by the Our World in Data website, much of its data sourced from the International Monetary Fund.

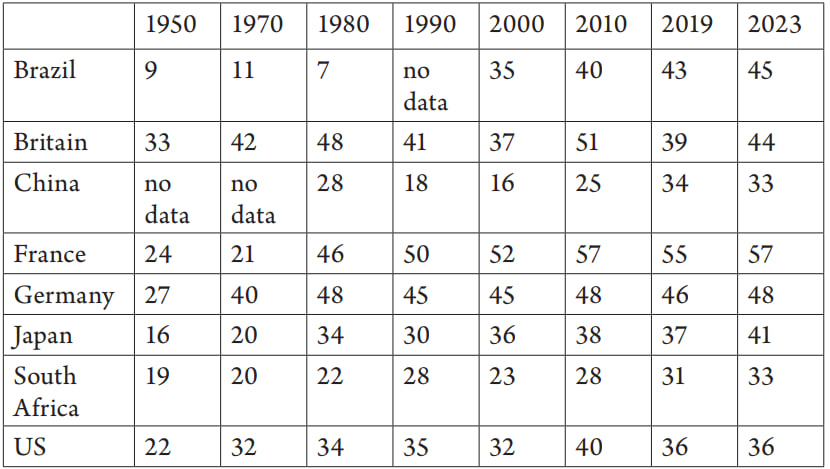

Table 1: Government spending as a share of national income (GDP)

Source: Our World in Data, 2025. Social spending covers health, old age, incapacity-related benefits, family, labour-market programmes, unemployment, and housing.

Table 2: Government social spending as a share of national income, selected OECD countries (GDP)

Source: Our World in Data, 2025. Social spending covers health, old age, incapacity-related benefits, family, labour-market programmes, unemployment, and housing.

Even under neoliberalism, spending on Britain’s NHS rose in real terms, albeit less rapidly than in earlier periods.30

The economic data then suggests strong grounds for contesting the exaggerated claim that economic globalisation entailed a fundamental erosion of state power. The main driver of neoliberal globalisation, the US, confirms this picture: according to OECD data, state spending as a proportion of GDP was 33.6 percent in 1979 (the beginning of the neoliberal era) and has never subsequently fallen below 34 percent. In 2023, the latest year for which OECD data is available, it was nearly 39.1 percent, having fallen from a high of 47.3 percent in 2020, after the response to the Covid-19 crisis.31 This general trend also applies to the other developed economies.

Of course, overall figures conceal a great deal of detail. The state’s taxation income may be steady or rising, but we need further work on who pays it, especially after the regressive shift from direct to indirect taxation and the establishment of self-declaration. Similarly, a break-down of health spending reveals a vast subsidy from generalised taxation and national insurance to private capital via the Private Finance Initiative, particularly in Britain. Additionally, internal markets and competition between health providers require a huge expansion of managers and accountants (partly paid for by cuts in the number of nurses and other medical staff). In sum, the headline figures do not indicate whether public spending that may have been market limiting/replacing in specific parts of society 50 years ago has given way to market-enhancing spending. More work is required in this area, but headline state spending levels across a wide range of countries emphasise the abiding centrality of the state in neoliberal capitalism up to the 2007-8 crisis and beyond.

This argument is strengthened when we critique the transnationalist Marxist perspective that developed in the academic area of international relations under globalisation.32 In the language of a major text-book on globalisation, transnationalists are “hyper-globalisers”.33 For transnationalists, capital was liberated from its national moorings by neoliberalism and grew so powerful that it could evade the regulatory powers of even the strongest states. States, in turn, were no longer the central institutions of economic management but merely parts of a decentred global economy, what the neo-Gramscian international relations scholar Robert Cox referred to as a “nebuleuse”.34 Within this, he argued, globalisation entails a tendency towards the unity of capital on a global scale, up-rooted from national attachments and regulated, if there were regulation at all, by a transnational managerial elite based in the international financial institutions.

One important empirical challenge to the transnationalist perspective was provided by the transnationality index produced by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). This index was devised to measure the degree to which transnational corporations had become global firms. It was comprised of a set of data measuring national sales against overseas sales, total assets and employment in the home national market compared with overseas. Unsurprisingly, major firms had a transnationality index of over 50 percent. The transnationality index for countries painted a different picture. Based on data such as foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows as a percentage of total investment, FDI inward stocks as a percentage of GDP and the contribution of overseas firms to national GDP and employment, the scores were far lower. Small countries, such as Denmark, Sweden and the Netherlands, have a relatively high transnationality index of around 30 percent. With larger countries, however, we see a significant decline: Britain and France have indices of around 20 percent, Germany and Italy around 10 percent, the US 6 percent, and Japan only 1 percent.35 UNCTAD also qualified the transnationalisation thesis when its assessment of FDI data for 1990-2003 led it to conclude that FDI accounted for only “8 percent of world domestic investment” and “only complements domestic investment”.36 UNCTAD’s data suggests that even when globalisation was at its height, the rather flat-earth claims of a “single global economy” were misplaced. As Ellen Wood argued, “the national organisation of capitalist economies has remained stubbornly persistent”.37

Even when capitals did restructure internationally under neoliberalism, it was generally within relatively narrow geographical limits: world FDI and trade were heavily concentrated within a triad of advanced regions—the European Union (EU), East Asia (including China, Japan and South Korea), and North America. UNCTAD noted that the concentration of FDI within this triad “remained high between 1985 and 2002 (at around 80 percent of the world’s outward stock and 50-60 percent for the world’s inward stock)”.38 The “footloose” quality sometimes ascribed to capital by globalisation theorists, and implied by many transnationalists, was thus quite limited.39 The production of use-values requires considerable cooperation between capitals, commodities being produced and sold within complex networks of production (including supply networks), finance and distribution. These networks remain densest at the national level.

A further reason for doubting the thesis that neoliberal globalisation entailed a significant retreat of the state was that it depended on state power in a quite crucial sense. The break with postwar consensus politics and welfarism, albeit within the limits discussed above, was linked to and enabled by major defeats for core parts of the labour movement in key countries (FIAT workers in Italy, the British miners, French steel workers, US air traffic controllers and so on). These defeats were reinforced by unemployment, which was increased dramatically by fiscal and monetary tightening, particularly by the Reagan and Thatcher governments. Capital was subsequently more confident to reduce its commitments to social welfare, restructure corporatist industrial relations and impose market discipline on labour. Enveloping the entire programme was an intensification of nationalism designed, in the words of Immanuel Wallerstein, to “shift exclusion from an open class barrier to a national, or hidden class, barrier”.40

In summary, under neoliberalism, states were re-shaped, the balance between their spending programmes shifted, but only states possessed the political legitimacy to impose the new shape of capital’s rule on subordinate classes and the capacity to police the arrangements when challenged. State functions are not fixed, and under neoliberalism, notwithstanding the persistence of welfare spending, it was mobilised to enrich the powerful and already rich and to moderate downwards redistribution. It became more linked to global flows of commodities and capital, more authoritarian and repressive, less committed to redistribution. Although the balance between the national and the global shifted, nowhere did economic globalisation render nation-states a “fiction” in a “borderless world” and government obsolete.41 As the French sociologist and anti-globalisation activist Pierre Bourdieu argued, it is not the state as such that has been in retreat but its left hand (“the set of agents of the so-called spending ministries which are the trace, within the state, of the social struggles of the past”). Meanwhile, the state’s right hand (“the technocrats of the Ministry of Finance, the public and private banks and the ministerial cabinets”) remained as powerful as ever.42 It was reinforced by states’ pursuit of measures to protect and enhance their own economies and major firms in response to the global financial crisis and further reinforced in response to the increasing rivalry in the international system accompanying the rise of China. The combined effects have been to generate new forms of state capitalism.

New forms of state capitalism

There is no single or universal model of state capitalism but a variety of state-capital configurations ranging from authoritarian statism to more liberal forms of economic management and statecraft. Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (abbreviated as the BRICS states), Western economies, energy-rich states in the Middle East and states located in the new growth centre of East Asia together reveal a patchwork of statist strategies. The differences between them arise from the uneven and combined development of capitalism as a world system, mediated by national histories and institutional arrangements, national patterns of class struggle, and global inter-state rivalry. However, nowhere do the new forms of state capitalism mark a fundamental rupture with neoliberalism. It is rather the latest adaptation of capitalism’s core imperatives under new constraints and political conditions. That adaptation combines elements that developed under neoliberalism (weak regulation of capital, particularly finance, and exclusion of labour movements from policy making institutions) together with new measures that are themselves conditioned by the uneven experience of capitalist crisis and the intensification of inter-imperialist rivalry it generates.

The 2007–8 global financial crisis marked a turning point. Governments nationalised banks, injected liquidity and resurrected some Keynesian tools. Ironically, at least for those who believe that China and the Labour Party are in some sense committed to socialism, it was China and Gordon Brown’s Labour government that helped stabilise global capitalism. Systemic crisis was reinforced by deepening inter-imperialist rivalry as a driver for a renewal of state economic activism. In this sense, the last decade or so has resembled the period before 1914, which informed Bukharin’s argument that intensified internationalisation generates a reverse tendency towards the increased nationalisation of capitalist interests. Four decades of globalisation have generated a renewal of international rivalry, particularly between the US and China, and forced states to pursue new measures to both protect and promote their interests and those of the major domestic capitals operating on their territory.

One obvious starting point for discussing contemporary forms of state capitalism is China. This case immediately throws up the problem of definition. In housing, for instance, roughly 95 percent is privately owned, compared to 63 percent in the US. Similarly, as we saw in table 1 above, overall state spending is lower in China than in the US and considerably lower than in Europe. Welfare spending is also low in China, and president Xi Jinping has spoken against welfare as an “idleness-breeding trap”.43 Against the US, Chinese banks are disproportionately state-owned (0 percent versus 51 percent), but state ownership is considerably higher in India and Russia (70 percent and 72 percent). The picture for productive capital is more clear-cut: the Chinese state owns 42.5 percent of corporate capital and the next highest figure among BRICS countries, the US and Britain is Russia’s 35 percent, with India and Brazil far lower at 17 percent.

However, state capitalism cannot be reduced to state ownership of capital. China’s SOEs produce roughly one-third of manufacturing output, but private capital is subject to very tight state control. All entities are defined as part of national security under the 2015 national security law and all must house a Communist Party cell, which influence corporations’ strategic decisions and hiring processes. State-owned banks are deeply inter-penetrated with SOEs, with over 80 percent of lending going to SOEs in many years. In Russia, while there is disagreement about the precise figure for the state’s share of GDP, it is clear that in the last decade or so, Vladimir Putin has reversed the post-Soviet liberalisation trend, increasing state control over the oligarchs who benefitted from privatisation under Boris Yeltsin, and undertaken strategic nationalisations of key corporations.44 SOEs dominate strategic industrial sectors in both China and Russia, and their own strategic position at the heart of each countries’ political-economy is underlined by the fact that while they only generate about one-third of output. They comprise over two-thirds of the value of stock market listings.45 Overall, as a recent analysis of the BRICS countries put it: “the state has a much larger role in steering economic activity, which is often discussed under the term state capitalism in the comparative capitalism literature”.46

The BRICS economies are not uniform, but in all of them state institutions, notably their financial systems, are more directly geared than Western finance towards supporting national capitals. This poses the question of whether the BRICS countries will continue to adapt to the liberal, US-dominated world financial order or whether domestic financial reforms and moves towards de-dollarisation might enable them to contest that order—and if such a possibility exists, might any innovations along these lines be capable of transnational extension? The recent expansion of the BRICS group seems, in part at least, to be related to these issues, even though the limited trade between BRICS members means that even its complete de-dollarisation would have only a limited impact on the dollar’s centrality to the world financial system.47 Nevertheless, Trump understood the threat to US power posed by an alternative world reserve currency when, in January 2025, he posted that if “these seemingly hostile Countries” create a new BRICS currency or “back any other Currency to replace the mighty US Dollar”, the US will impose 100% tariffs on them.48

Trump’s comments highlight that the issue of de-dollarisation should be set against the background of deepening inter-imperialist rivalries and a reassertion of state economic activism. Some developments, such as the sovereign wealth funds of energy-rich states that have become an everyday part of capitalism in the last two decades, suggest that it is late-comers and less developed catch-up states that have intensified their state capitalist measures. However, as global tensions have increased more economically advanced states have also become more active in strategic sectors. Trump’s first-term response to the rise of China as its main contender included a tech-war against major Chinese firms, such as Huawei, and restrictions on high-tech exports. The restrictions were extended under Joe Biden, who pursued a revamped industrial policy to strengthen the US relative to China. This included the 2022 Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors (CHIPS) and Science Act, which directed $280 billion (£213 billion) towards high-tech sectors, as well as inducements to global high-tech capital to establish new production sites in the US. This return to activism meant that the announcement of DeepSeek’s Artificial Intelligence (AI) model in January 2025 felt like a contemporary Sputnik moment for the US. Developed at a cost of $5bn (£3.8 billion), against the hundreds of billions spent by Western AI models like ChatGPT, DeepSeek showed that Western restrictions have accelerated the development of Chinese high-tech, which benefitted from support from the $150 billion (£114 billion) China Integrated Circuit Investment Industry Fund. This poses a threat to US technological leadership in key consumer industries and in the military sphere, where the military-industrial complex continues to anchor the US economy.

China and the US are caught in a tit-for-tat rivalry in high-tech sectors. In response to DeepSeek, the Trump administration accelerated state initiatives in defence of US capital. It issued thinly veiled threats to Ukraine, trading military support for access to strategic minerals, including the rare earths whose production is dominated by China. These are vital for a range of consumer technologies, including renewable energy, AI, robotics and electronic vehicles. They are also indispensable for the latest military technologies, including missile targeting. Ukraine has deposits of 22 of what the EU defines as 34 critical minerals, while Greenland has deposits of 90 percent of the world’s critical minerals. It is not hard to detect US geostrategy behind Trump’s interest in these countries.

Trump’s aggressive economic statecraft is designed to maintain the US’s leading position against China (as well as Western rivals like Japan and the EU). In the 1980s, the US used the Strategic Defence Initiative (SDI, also “Star Wars”) to update its industrial base around the military-industrial complex, including aerospace, computing, engineering and electronics. The Star Wars programme awarded the overwhelming majority of research and other contracts to US firms and represented a giant arms-centred industrial policy, designed, according to John Palmer, to restore the US to “an unchallengeable position in world hi-tech leadership over the Europeans and the Japanese”—of the total spent on SDI up to the end of 1986, only 0.7 percent went to European firms.49 Via various intermediary steps, the beneficiaries today appear as firms like Microsoft, Apple and Google over which US allies such as the EU express disquiet due to the huge state support they are receiving via US defence spending. Regular transatlantic tension over Boeing and Airbus, and over US dominance in the digital economy, show that even between long-term allies, state support for “national champions” remains a source of conflict.50 This is likely to increase under Trump’s plans to update Star Wars with a space-based missile defence system, “Golden Dome”.

Conclusion: why this matters for the left

Under capitalism, politics and economics are formally separate and occupy distinct institutional spheres, but they are unavoidably inter-penetrating and inter-dependent. Exchange relations in the market (especially in the labour market) would not survive for long without the support of coercive relations of non-exchange. For capital, the corollary is that it exists in a relation of structured interdependence with the state.51 This is an historical relationship that is neither fixed and unchanging nor characterised by linear change. The balance of power between the two sides ebbs and flows, but capital has never been, nor can it be, “liberated” from its ties to states.

The ascendancy of state capitalism for much of the 20th century was undermined by the neoliberal revolution, under which the state retreated across a number of areas and policy domains (particularly reduced support for declining industrial sectors and nationalised industry). However, even in its supposed retreat, the state never vanished—it reconfigured its functions and resurfaced with renewed prominence after the 2008 crisis.

The balance between the national and international also changes historically, but it is a permanent concern of all states, which are always Janus-faced. To argue that national economies can simply adjust to global imperatives is at best one-sided, and, as Philip McMichael writes about one of the key transnationalist theorists, William Robinson, such an approach “suspends the dialectic”.52 States, particularly the most powerful, are not passive recipients of international pressures but active agents that promote the interests of domestic capitals and seek to strengthen the wider national economy. States have not been fundamentally or irreversibly weakened by globalisation, and global capitalism continues to be shaped by the actions of both the major capitals and the most powerful of the world’s states, within whose jurisdictions those capitals are largely based.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the rise of labour movements and the left played an important part in forcing states to adopt measures to tame the “destructive mechanism” of the market. This, the second part of Polanyi’s double movement, is not an immediate concern for today’s ruling classes. State capitalism was also, as Bukharin emphasised, a response to internationalisation. Entangled in increased inter-imperialist rivalry, states sought to export crisis and protect their own parts of the world system. There are echoes of this in today’s resurgence of state capitalism in response to the internationalisation promoted under neoliberal globalisation and particularly the rise of China and the intensification of inter-imperialist rivalry. These responses have been amplified by the pressures of what Michael Roberts calls the “long depression” afflicting the global capitalist system.53

The resurgence of state capitalism demands clarity and principled arguments from the global left. As the world teeters on the edge of climate catastrophe and populist-nationalist violence, socialists need to argue:

1. State capitalism is not a progressive alternative to neoliberalism but a tool for managing capitalist crises and international rivalry. Whether authoritarian or liberal-democratic, the capitalist state remains committed to accumulation and the power of the capitalist class. The state may play a more active role in the economy in Xi’s China and Putin’s Russia, for example, but these are not models that socialists can support. Both societies are highly unequal, and social spending and household consumption as proportions of national income are even lower than in the West.

2. Statism may contain progressive elements, as with the British NHS, but state economic activism usually entails support for capital.

3. The revival of state capitalist measures highlights that state power is not separate from capitalism and capital accumulation but central to both.

4. The state is not a neutral arbiter but a class instrument. It enforces property rights, disciplines labour and seeks to sustain profitability. In recent decades, welfare reform has been shaped to enable, not restrain, capital.

5. Nationalism, within which state capitalist measures have always been framed, remains a strategic tool for ruling classes as they aim to consolidate their power and legitimacy and fragment working-class solidarity. As inter-imperialist rivalry intensifies so too do state assertions of nationalism and supremacy.

6. Where labour movements fail to challenge nationalism and the racism with which it is associated, they fail to overcome an obstacle to independent working-class activity and the internationalist solidarity that is key to the struggle for socialism. Workers’ solidarity must transcend borders.

7. Socialists fight on the terrain and issues that capitalism generates, primarily at the national level. However, as Antonio Gramsci argued, “the point of departure is national—yet the perspective must be international”.54

Adrian Budd teaches international relations at the University of Hertfordshire and is the author of China: Rise, Repression and Resistance (Bookmarks, 2024).

Notes

1 Thanks to Anne Alexander, Joseph Choonara, Rob Hoverman, Sheila McGregor and Nick Moore for comments and suggestions on this article in draft. I also benefitted from discussions at online meetings of the Marxist Political Economy Group and of the Republican Labour Education Forum.

2 Economist, 2012.

3 Ten Brink, 2023.

4 See in particular Harman, 1991. See also Kliman, 2008; Callinicos, 2023, chapter 3; Choonara, 2021 and 2025.

5 Marx, 1954, p751. For a longer analysis, see Miller and Dale, 2023.

6 Polanyi, 1957, p139.

7 Polanyi, 1957, p140.

8 Marx, 1973, p507.

9 Harman, 1991.

10 Luxemburg, 1989, p43. Chapter 4, on capitalism and the state, from which this quote comes, repays careful reading today.

11 Marx and Engels, 1942, p218.

12 Polanyi, 1957, p76.

13 Polanyi, 1957, p57.

14 Luxemburg, 1989, p44.

15 Ellen Wood, 2002, p37.

16 Michael Löwy rightly criticised the Communist Manifesto for “a certain economism and a surprising amount of Free Tradist optimism” when it argued that capitalism’s expansionary dynamic “batters down all Chinese Walls”, and that “national differences and antagonisms between peoples are daily more and more vanishing”—Löwy, 1976, p82; Marx and Engels, 1942, p209, p225. Capitalism both batters down and erects protective walls around national economies.

17 Bukharin, 1987, p36.

18 Bukharin, 1987, p62.

19 Coates, 2000, p226.

20 Harvey, 1999, p25, fn12

21 Heitlinger, 1979, p139.

22 Sally Kincaid’s forthcoming article in this journal shows the striking similarities between the experiences of women in China after the 1949 revolution and the Soviet Bloc. Under Mao Zedong’s national-developmental project immediate gains were real (divorce rights, increased paid work, some collectivisation of the reproduction of labour power via communal dining and laundries), albeit that legal rights were frequently limited in practice. However, here too women remained responsible for housework and childcare and their unpaid labour continued to subsidise the country’s economic development. This pattern has persisted into the post-Mao reform period, which is the focus of Kincaid’s article. In 2023 Xi Jinping gave official endorsement to the highly privatised nature of social reproduction, encouraging the All-China Women’s Federation to foster traditional gender roles as part of “the traditional virtues of the Chinese nation” as well as “good family traditions” and the cultivation of “a new culture of marriage and child-bearing”.

23 Reiman, 1987, p86.

24 Quoted in Deutscher, 1966, p328.

25 Reiman, 1987, p86.

26 Castles, 2007, p2.

27 For the latest data see OECD, 2025. The COFOG classification is outlined in annex I.

28 Castles, 2007, p11.

29 Castles, 2007, p21. The savage austerity of the 2010s changed the picture somewhat, but pre-2008 data suggests no simple correlation between globalisation and the retreat of the state.

30 Arnold and Jefferies, 2025.

31 OECD, no date.

32 For a critique, see Budd, 2007.

33 Held and others, 1999. It should be pointed out, however, that not all those working within a transnationalist perspective adopted the most extreme view of, for instance, William Robinson. Many of the members of the Amsterdam School of International Relations, for instance, agree with Henk Overbeek’s argument that “transnational neoliberalism manifests itself at the national level not as a simple distillate of external determinants, but rather as a set of intricate mediations between the ‘logic’ of global capital and the historical reality of national political and social relations”—Overbeek, 1993, pxi.

34 SOURCE

35 UNCTAD, 2008, p12.

36 UNCTAD, 2004, p3.

37 Wood, 2003, p23.

38 UNCTAD, 2003, p23.

39 Productive capital’s relative geographical immobility parallels a frequent immobility between industrial sectors. Car producers’ profit rates fell from 20 percent in the 1920s to 10 percent in the 1960s and 5 percent in the 21st century, but they remained committed to the sector in which their fixed investments were sunk.

40 Wallerstein, 1998, p 21.

41 Ohmae, 1994.

42 Bourdieu, 1998, p2.

43 According to the China Labour Bulletin website, shortly before it closed down in mid-2025, the Chinese state wanted “to reduce the social insurance burden faced by employers and shift the burden of pension and other social insurance contributions onto individual workers”.

44 See Arshakuni and Yefimova-Trilling, 2019.

45 See the special report on state capitalism in the Economist, 2012.

46 Petry and Nölke, 2022, p4.

47 Afota et al, 2024. The expansion of the BRICS group—now BRICS plus—includes Egypt, Ethiopia, Indonesia, Iran and the United Arab Emirates.

48 Trump, 2025.

49 Palmer, 1988, p72; p197, fn26.

50 See, for an example of European concerns, James, 2004.

51 Major capitals may have a home state but they also have deep relations with other states. Hence, in his important 1991 article on capital and the state, Chris Harman preferred “trans-state capitalism” over “transnational capitalism”—Harman, 1991, p33. This registers that even giant firms do not operate beyond states, as could be imagined with “transnational”, but rather multiply the number of states with which they establish some degree of interdependence. It thereby recognises both continuity and change: the complex of relations between capitals and states (and indeed labour movements) did change under neoliberalism, but capital remained tied to states in a variety of ways.

52 McMichael, 2001, p201. Robert Cox argued that nation-states once provided a “bulwark defending domestic welfare from external disturbances” but, under neoliberalism, became “a transmission belt from the global to the national economy”—Cox, 1992, p31.

53 Roberts, 2016.

54 Gramsci, 1971, p240.

References

spending.html