Sean Vernell’s article, “The Working Class, Trade Unions and the Left: the Contours of Resistance” (available on the International Socialism website), is a very welcome assessment of the legacy of the wave of strikes that took place over the issue of pensions across public sector trade unions between March 2011 and June 2012.1 Sean offers a comprehensive overview of the impact of the strikes, their novelty in terms of (among other things) the coordination between the different unions, the internal dynamics within a number of the unions that were pivotal in the strikes (especially those of the University and College Union, UCU) and observations and perspectives relating to strategy for the trade union activists who played central roles at different levels of the movement and for those who came into activity for the first time through it. It is an analysis that deserves serious engagement by workplace activists seeking to learn the lessons of the pensions campaign and overcome the impasse created by the failures of the official leaderships.

It is in that spirit that I raise an argument with some of Sean’s formulations: particularly those supporting his discussion of the mass strike. Specifically, Sean rejects the characterisation of the pensions strikes as having been (simply) “bureaucratic mass strikes”, describing this position as “too abstract” and as revealing “a deeper misunderstanding of the character of the struggle today”. I will argue that in their dominant characteristics the pensions strikes (and particularly 30 November 2011) were indeed “bureaucratic” and that this is something that needs to be properly understood rather than glossed over. I also argue that this does not in any sense diminish the authentic rank and file activism within them and, indeed, that the experience of that strike wave points to the potential and importance of local organisation more compellingly than is gestured to by Sean. I will focus on the limitations of the one-day public sector strike that has been the preponderant form of strike action over recent years across the British working class movement and within these limitations the opportunities it nonetheless creates—if properly understood. In making my argument I will draw on the experience of building for N30 in my own city of Liverpool to explore what a rank and file perspective can mean specifically in relation to the one-day mass strike. This will, I know, make some of the illustrations seem localised and perhaps provincial: however, I can only speak of what I know.

The bureaucracy and the rank and file

In their analysis of the British General Strike of 1926 Tony Cliff and Donny Gluckstein put forward a critique of Lenin on the question of the trade union bureaucracy.2 Borrowing from Marx’s and Engels’s assessments of the British union bureaucracy, Lenin had formulated the “aristocracy of labour” thesis. Responding to the calamitous collapse of the European labour movement in the face of the nationalist war frenzy of August 1914, Lenin outlined a materialist analysis of the official trade unions in the Western bourgeois democracies. For Lenin the fruits of empire in many of the Western European countries permeated down from the bourgeoisie into the middle classes and also to a narrow layer at the top of the working class.3 This created a psychology and politics of “opportunism” within the trade unions that, at decisive moments, would always derail confrontations with employers and with the state. This, for Lenin, was also the basis of reformism. Indeed he came close to including the whole of the British and German trade union movements, leaders and members, within this analysis. For Lenin then, it was only the lowest paid workers (the “lowest strata”) who could ultimately be counted on to oppose capitalism and war. The revolutionary episodes in the Western European countries that came with the end of the First World War, in which engineers and other groups of skilled workers played central roles, exposed the weakness of this assessment. Developed at a great distance from the British experience and in conditions of illegality for trade unions in Russia, Lenin’s formulation also entailed some major simplifications. Crucially, it could lead to the ultra-left position that the fight for better wages represented a kind of complicity with imperialism. It also inclined towards a romanticisation of unorganised workers as representing a kind of pure reservoir of revolutionary potential.

In Cliff and Gluckstein’s recalibration of Lenin’s formulation the roots of reformism go far deeper than a narrow layer of relatively well salaried and highly skilled workers. Rather reformism, as a political psychology as well as an articulated political system, affects all parts of working class movements within liberal democratic countries. It was not then something that could be sloughed off in a wave of pure proletarian struggle by the “lowest strata”. In turn, this meant that involvement in the trade unions was unavoidable for Marxists, and so also were the pressures towards assimilation within the trade union machine.

For revolutionaries within the trade unions this raised significant complications that had not been faced by the Bolsheviks. Crucially, Cliff and Gluckstein argued, it created the twin dangers of adaptation and abstentionism: “There are dangers of too great a concentration on official influence at the expense of the grass roots, or an abstentionist approach which leaves the rank and file under the tutelage of the officials”.4

This reassessment was a prelude to a searching critique of different types of rank and file organisation in the history of the British trade unions. We will refer to this critique, and to perspectives on the subject by other contributors to this journal, in the concluding discussion. Now, however, we will elaborate further upon the character of the trade union bureaucracy in its most general features and behaviour. There are a number of key and interrelated characteristics of trade unions that are important to understand:

- Trade unions are “sectional”. They both unite and divide the working class: unite, that is, within workplaces and across trades; divide between trades (and so also within workplaces).

- Trade unionism matches the “geography of capitalism” in that the technical aspects of the labour process must dictate the form of the struggle between capitalists and workers and therefore of the types of issues that arise.

- Trade unions exist to maintain and, where possible, improve the conditions under which work is organised within these sectional and technical constraints.

- In this organisational context a layer of salaried officials emerges (the trade union bureaucracy) whose function it is to represent the work-related interests of their worker-members to the capitalists and their management functionaries, as negotiators, acting as mediators in the exploitation nexus.

- This layer is relatively privileged insofar as trade union officials are not subject to the discipline of the workplace or the assaults of the employer with respect to pay and conditions of work in a direct sense.

- The interests of the trade union bureaucracy lie then primarily in the maintenance of the trade union machine (its assets and income) and secondarily in the working conditions of its members.

- All of the above means that trade unions—at least those that have evolved in historically non-revolutionary periods—can never be revolutionary in purpose or effect.

- The trade union official is “Janus-faced” in that she or he must maintain credibility both with trade union members (in expressing and up to a point mobilising their grievances) and with the capitalist employer (as a figure who can both threaten the employer with industrial action, and also restrain members’ militancy at the crucial moment for the purpose of collective bargaining).

- This contradiction leads to splits in the bureaucracy insofar as some of its parts will lean more towards the mobilising aspects of the purpose of the trade union and some more towards its bargaining functions.

- This means that trade union officials differ ideologically between a left and a right (something which revolutionaries must recognise if they are to avoid the twin pitfalls of adaptation on the one hand and abstentionism on the other).

As Cliff and Gluckstein argue:

In leading workers’ struggles, the revolutionary party must have its priorities clear. It must start from the basic contradiction under capitalism: the contradiction between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie. It must also take into account a secondary contradiction—that between the trade union bureaucracy and the mass of workers—and a third: the division inside the bureaucracy because of its dual nature. Pulled in different directions by the force of the two major classes in society—the bosses and the workers—arguments develop among the bureaucrats.5

This schema sets out parameters for any assessment of the behaviour of trade unions at the national and local levels and across a range of axes: between the confidence of the capitalist class (the severity with which they threaten and act against workers) and the ability and willingness of workers to resist; between the unifying and dividing (sectionalist) tendencies across trade union memberships; and between the relative influences of the left wing of the trade union bureaucracy and its right wing. Each of these axes interact with one another. Where workers are unable to defend their own interests by independent action with respect to their own employers, for example, they are unlikely to be able to overcome the sectionalism that divides them from other groups of workers. Similarly, where workers remain divided along sectionalist lines they are more likely to remain dependent on the bureaucracy for any ability to resist their employers’ offensives. Only by understanding each of these different pressures in relation to one another can each factor be accorded its proper weight in understanding the direction of travel of the trade union struggle and in deciding upon an effective orientation within it.

The bureaucratic mass strike: Cliff’s formulation

The limitations of the mass strike

Tony Cliff described Belgium, in his analysis of the mass strike there in 1961, as a “laboratory” of the general strike.6 With this phrase he was echoing Rosa Luxemburg who had urged the workers’ movements of Europe to learn to “speak Belgian”. Cliff, and before him Luxemburg were pointing to the high incidence of general strikes in the history of the Belgian working class movement. Between 1886 and the 1961 strike there had been no fewer than eight general strikes in Belgium. This was a direct reflection of the high rate of industrialisation in Belgium from the 1890s onwards. As Chris Harman was to explain much later, the pattern of mass strikes has followed the patterns of industrial concentration across the world:

The general strike is a form typical of class struggle in large scale modern industry. It comes to the fore when the development of the class struggle has reached the point where action in one industry has an immediate impact upon every other industry and upon the state.7

However, Cliff was doing more than simply commenting on a particular episode in the history of the Belgian trade unions. He was developing a critique of the limitations of Luxemburg’s analysis of the mass strike itself. Luxemburg had described the general features of such strikes in her celebrated 1906 pamphlet The Mass Strike and elsewhere.8 Capturing the momentous power of working class action in the mass strikes she observed in her day, she described their spontaneous and explosive character: the ways in which economic demands transformed swiftly into political demands (and vice versa); the overcoming of sectionalist divisions; the ways in which workers learnt and developed in consciousness, representing a “spiritual” growth; the challenges that they threw up to the capitalist state; and the potential for workers’ revolution that they created. However, the strikes that Cliff was addressing had revealed another property of the mass strike in the context of an established bourgeois order: the ability of labour bureaucracies to control them. In 1935 Trotsky had argued:

The parliamentarians and the trade unionists perceive at a given moment the need to provide an outlet for the accumulated ire of the masses, or they are simply compelled to jump in step with a movement that has flared over their heads. In such cases they come scurrying through the back stairs to the government and obtain the permission to head the general strike, this with the obligation to conclude it as soon as possible without any damage being done to the state crockery. Sometimes, far from always, they manage to haggle beforehand some petty concessions, to serve them as figleaves. Thus did the General Council of British Trade Unions (TUC) in 1926.9

In 1961, abandoned by their leaders, Belgian workers were unable to take control of events and the general strike collapsed.10 What Cliff addressed then was this question: how is it that the official “machine”—the trade union bureaucracy in alliance with the political forces of social democracy, of the right and the left—can, at decisive moments, pull the rug from under the feet of the mass strike, sometimes with devastating consequences for the workers’ movement? What he identified in the pattern of all Belgian strikes, from 1961 back to 1894, was the element of bureaucratic “discipline”. This took various forms but often included the centralisation of propaganda materials, the control of the timing and organisation of demonstrations, the careful selection of orators and even the creation of special labour “strike police” whose role it was to steward the movement and deal with “irresponsible” elements. As he said of the Belgian strike of 1913: “If they were pushed into the strike by the masses, they never lost their control, which was practically complete, over all the levers of the strike”.11

More than two decades later and responding to the defeat of the British miners’ strike of 1984-85, Cliff was substantially to expand his argument and in ways that are of direct relevance to the debate today. In two significant publications, “Patterns of Mass Strike”12 and Marxism and the Trade Union Struggle: The General Strike of 1926,13 Cliff developed his analysis but now with greater historical detail. In the first of these publications he described two “extreme” types of bureaucratic mass strike: Sweden 1909—the extreme illustration of the “purely political” mass strike; and Belgium 1913—the extreme illustration of the “purely economic” mass strike. Over and above this schematic categorisation of bureaucratically controlled strikes, however, two archetypal manifestations of the mass strike per se were now apparent. There was the spontaneous, explosive, creative and pre-revolutionary mass strike of Luxemburg’s formulation; and now its disciplined form, initiated and controlled according to the agendas and political timetables of the labour bureaucracy.

In framing his analysis Cliff cautioned against dogmatic formulations. Any actual mass strike was not to be shoehorned into one or other of these types. Rather each particular episode of mass working class strike action would require concrete historical analysis with attention being paid to its dominant characteristics as well as a proper weighting of its specific factors. Only with this type of empirical scrutiny could it be determined whether the classical model of Luxemburg’s mass strike or that of the bureaucratic mass strike was most appropriate—and to what degree. To illustrate his spectrum Cliff discussed three examples: the 1926 British general strike; the 1972 British miners’ strike; and the 1968 French general strike. Through these discussions he drew generalised conclusions that bear directly upon how we understand the relationship between the bureaucracy and the rank and file of the trade unions.

Three case studies: Britain 1926

Cliff characterised the 1926 British General Strike as having been nearer to the bureaucratic mass strike than to the Luxemburg formulation. Strenuous efforts were made to pacify strikers. The local strike committees, or Councils of Action organised mainly by the trades councils, were bureaucratically controlled. The strike ended after just nine days, too short a time for rank and file initiatives to develop. However, it is also the case that significant disturbances and confrontations with the police did happen in some parts of the country. Strikers were radicalised—representing “a real spiritual growth”—leading to significant recruitment to the Communist Party as well as the seven-month refusal of the miners to buckle in the face of the employers’ lockouts.14 Nonetheless, despite these significant features of the strike and its aftermath, never at any stage did the rank and file threaten the TUC’s control of the strike.

While characterising the 1926 general strike as “bureaucratic” in its main features, Cliff also analysed the background to the strike in order to explain why the trade union officials had been able, with very little difficulty, to “turn off” the strike when it suited them. Crucially, a decline in shop floor confidence following a decline in industrial action had damaged workers’ collective ability to act independently of the officials:

Thus the historical background to the 1926 general strike was a descent from a pre-revolutionary situation in 1919 to the almost complete disappearance of shop stewards’ organisation, lack of confidence of rank and file workers, and therefore the heavy dependence on the trade union bureaucracy.15

By way of contrast Cliff considered two other mass strikes, asking why French workers in 1968 didn’t simply side with the forces of “law and order” against the students (as had workers in Germany and the US) and why, in 1972 in the UK, engineers and power workers did come to the aid of the miners. Underlying the responses to both of these questions lies a common thread: over the preceding years workers had built up sectional and workplace militancy and organisation through a series of localised and sectional struggles combined with national mass strikes, from which generalised confidence and consciousness had grown.

France 1968

In France students staged their largest ever strike on 20 November 1967. This was followed by a series of demonstrations and protests by university and school students that culminated in the “Night of the Barricades” on the night of 10 May 1968. Following a meeting of the French National Union of Students and Communist Party and Socialist Party affiliated trade union leaders, 13 May was declared a general work-stoppage day in support of the students, bringing 10 million workers out on strike—the largest mass strike in history. But what is of most importance to note here is that, while the union leaders had imagined a one-day token strike which would be dominated by French nationalist flags and slogans, in reality the flags were solidly red and the left slogans of the students were the ones taken up by workers on mammoth demonstrations across France.

The background to the strike was the two preceding years that had seen a rise in factory struggles. The Communist Party-controlled trade union federation, the CGT, had mounted a number of demonstrative regional and national days of action. In May 1966 and again in February 1967 they had called strikes across all trades. The result of this had been lockouts of workers at the Dassault aircraft factories in Bordeaux and of steel workers in Villerupt which led in turn to solidarity strikes across those sectors. Further strikes and factory occupations now occurred of textile workers, truck makers, metal workers and shipyard workers. This phase of the strike wave led to a one-day general strike to protect state social security arrangements on 17 May 1967 called by the Communist and Socialist trade union federations. This was followed by a renewed wave of strikes by Renault workers at Le Mans and Cannes in which barricades were built and which saw violent clashes with the CRS police.16 The reason, then, that in the following year the May-June 1968 French strike was close to the “model of Russia, 1905”, lay in the willingness of French workers to fight over their own issues and to generalise from those struggles. The same was true of Cliff’s third case study, the 1972 UK miners’ strike.

Britain 1972

From the start of the 1972 miners’ strike the levels of strategy and coordination of picketing were extraordinary. Power stations, coke depots, railway depots and all main docks were picketed across the country. Power workers, railway workers and dockers responded well and liaison committees began to emerge. Following an appeal by miners seeking to close one strategically important coke depot at Saltley outside Birmingham, 100,000 engineers and power workers walked out in sympathy and 20,000 marched to Saltley to close it down. The 1972 strike was “in effect a rank and file strike”.17

But it is again the background to the strike, and crucially to the solidarity shown by different groups of workers, that is of most interest to us here. During the 1960s the downward pressure on wages in the UK had produced a pattern of militancy at both the national level and within thousands of workplaces up and down the country. Moreover, the great majority of work stoppages had been unofficial. In February 1971 something approaching 2 million workers came out on strike—mostly unofficially—against the Industrial Relations Bill.18 It was against this background, as well as a round of area-wide pit strikes and the breakdown of national bargaining talks on pay, that the National Union of Mineworkers gave its first national call-out since 1926.

More specifically, the power workers had been an important group in the “wage explosion” battles between 1969 and 1970, winning a 10 percent rise through largely unofficial action. Among the engineering workers the best organised and most militant in the Birmingham city region were those in the motor industry. Industrial action on pay had been led for many years by the British Motor Corporation Joint Shop Stewards Committee that operated across the cities of Birmingham and Coventry. In 1970 there had been five major stoppages in the Birmingham car plants and 11 in other engineering plants. In 1971 a further nine stoppages occurred in the car plants. When the miners turned to the power workers and Birmingham engineers their appeal met a receptive and willing audience. The result famously was the closing of the Saltley depot.

The axes of militancy

As we have seen with respect to a general framework by which to assess the behaviour of the trade union bureaucracy and now with his analysis of three mass strikes, Cliff identified the three dominant factors that determine the ability of workers to take action independently of their official leaderships:

The relative confidence of workers in the face of their employers, the relations between the rank and file and the trade union bureaucracy and the depth of sectionalism dividing workers. All three are interrelated and all are relative.19

In 1926 in Britain, following a seven-year downturn in industrial militancy, workers were not confident in taking action against their own employers and so, despite there having been some areas of combativity, they remained dependent on their official leadership. In 1968 in France, however, the local strikes and lockouts that had occurred before the May general strike, and that had in the main gone down to defeat, had created a legacy of battle experience and self-organisation. In the UK in 1972 the experience of the power of workers and engineers in fighting over their own pay settlements meant that they were confident in taking on their own employers and so were responsive to the call for solidarity.

The key generalisation that emerges from each of Cliff’s studies is that any particular mass strike cannot be understood in isolation. Rather it must be understood against a recent background of the highs and lows of sectional and more generalised industrial action that have led up to it. It is not necessarily that this background must be one of continuous success. This was not the case, for example, in France before the 1968 strike. It is as much to do with the lessons drawn from struggles, making crucial the theme of how workers learn from the experiences both of victory and defeat. It is in this sense that all of the elements that Cliff identifies are both “interrelated and relative”.

The 30 November 2011 pensions day of action

Charlie Kimber vividly described the splendour of the day of coordinated strike action to protect public sector pensions on 30 November 2011 in this journal in the immediate afterglow of the day itself.20 Without reciting every aspect of the day and its impact, a few of its more remarkable features are worth recalling here. More than 2 million workers took part in the strike: comparable to the number that struck against the Industrial Relations Bill in 1971 and certainly the largest official strike since 1926. The number of participating unions was also historic. All told, 29 TUC affiliates struck on the day ranging from one of the giants of the trade union movement (Unison), across the large public sector unions—National Union of Teachers (NUT), Public and Commercial Services Union (PCS), National Association of Schoolmasters Union of Women Teachers (NASUWT), University and College Union (UCU)—the public sector sections of some large unions (Unite and GMB), smaller public sector unions (Undeb Cenedlaethol Athrawon Cymru,21 Prospect, FDA,22 National Association of Head Teachers, Napo,23 etc) and including also a number of professional body TUC affiliates (Society of Chiropodists and Podiatrists, Association of Educational Psychologists, Aspect, etc). This level of coordination across the trade union movement was quite unprecedented.

Finally, at the local level the reports were of impressive mobilisation and big turnouts for rallies: 10,000 in Leeds, Brighton and Newcastle; 20,000 in Bristol, Liverpool and Birmingham; 25,000 in Glasgow and Manchester; and 50,000 in London. Probably more than half a million people in total took part in demonstrations.24 There is far more to say about the experience of N30 and Kimber’s 2012 article describes what happened in some detail. However, there was a paradox to the strikes that was largely eclipsed by the excitement of the day and the sense of potential that it created; one that Kimber pointed to clearly:

One of the contradictions of the present situation is that we have just seen the biggest strike since 1926, and yet earlier this year the Office for National Statistics reported: “In the 12 months to March 2011 there were 145,000 working days lost from labour disputes, the joint lowest cumulative 12 month total since comparable records began in the 12 months to December 1931.25

This was something that needed to be addressed because if the party had been great, the hangover was terrible. Over the next few weeks and months activists watched in disbelief as each of the leaderships of the largest trade unions caved in to pressure from the coalition government, signing up in turn to the “Heads of Agreement” put in front of them by the Chief Secretary to the Treasury, Danny Alexander. It is true, as Sean emphasises, that in the case of the NUT, PCS and UCU, under the pressure of motions from branches, local associations and conference votes, active campaigns continued into the spring. The result, however, was the same—the defeat of the pensions revolt.

Every conceivable obstacle normally used by official trade union leaderships not to fight had been removed: the strikes were popular;26 the coalition government on the other hand was hugely unpopular as it stumbled from crisis to crisis; the action was lawful with all the participating unions having balloted successfully; the unions were acting together; and the great majority of these unions had mandates for action that would be live well into the following year. And yet still the official leaderships walked away from what millions of workers believed was a victory there for the taking. The question this left hanging in the air (and that remains still) is simply this: how could it have happened? Or rather how could we have let it happen? To be clear, the “we” here is not aimed at the thousands of activists who over those weeks and months fought determinedly inside their unions to prevent the debacle. It is rather “we” as a movement that is meant, rhetorically. However, it is a question that must be answered because the reality within the movement underlying the contradictory strike figures can intensify the tendencies towards adaptation within the trade union machine on the one hand and abstentionism (or ultra-leftism) on the ground. To answer this question, and mindful of the paradox highlighted above, we will adopt the approach utilised by Cliff in his studies of the mass strike in history.

Considering the pressures that were acting upon the bureaucracy, clearly, the officials were not faced with direct pressure from active rank and file workers. The extraordinarily low strike rate in the UK in the years immediately preceding the 30 November strike meant that the official control of the movement was never in question. However, workers were angry with the coalition government, deeply worried about pensions and public services and frustrated with the slowness of their leaders to act. This was borne out in numerous conferences and union elections with left caucuses gaining ground in a number of large unions in the years leading up to the pensions revolt. More important for the officials was the sheer scale of the assault on state services: a scale that threatened the membership bases of the public sector trade unions. A not so hidden agenda to the devaluing of pensions, for example, was that of removing the obstacle to the privatisation of health and welfare services represented by employers’ pension fund contributions.

The immediate problem for the public sector unions was the 2010 Comprehensive Spending Review (CSR). The cuts contained in the CSR were savage (and have of course been compounded by further cuts since). In it the coalition government announced spending reductions of £81 billion by 2014-15 with £11 billion coming through welfare cuts and £3.3 billion as public sector pay freezes. These cuts were also to be accompanied by new mechanisms for and pressures towards outsourcing and privatisation as well as new funding mechanisms based on future tax returns on current investments intended as an alternative to state funding for local government.

In the early part of 2011 this is what union officials were confronted with. For public sector unions, and particularly those whose membership base was exclusively in local and national government run services (Unison, PCS, NUT, etc) the cuts not only threatened hundreds of thousands of jobs but also fundamentally the raison d’être of public sector trade unionism itself in terms of political leverage, national collective bargaining and, in the case of Unison, of the partnerships with government offices established during the Blair-Brown years. However, properly to understand the impact of N30 and what it tells us about the current state of the trade union movement in Britain, we need to see it in relation to the character of the struggles that led up to it. To do this we can make use of the labour disputes data of the Office for National Statistics (ONS).27

The 2011 figures show that 92.7 percent of “working days lost” and 96.2 percent of the workers involved are accounted for by strikes that lasted just one day (with N30 naturally accounting for the majority of these days). Numerically, 87.3 percent of all disputes lasted for five days or less. The ONS also reports that the 2011 “spike” in the statistics was caused by a small number of national public sector strikes. Finally, the overwhelming majority of disputes (95 percent of “working days lost”) in 2011 were over pay (with pensions included as “pay”). From the ONS statistics then a clear picture emerges. The great majority of strike action in 2011 took place in the public sector. It was national in character and of very short duration (normally one day) and it was over pay. More importantly, this conforms to a general pattern in the strike figures over previous years leading up to 2011.

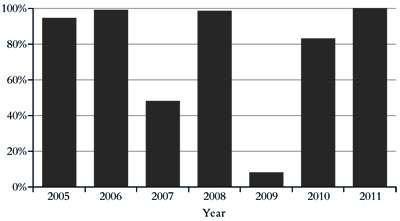

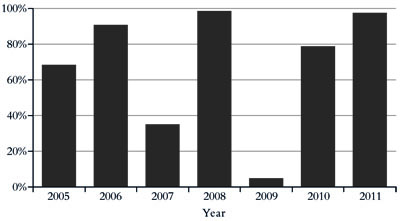

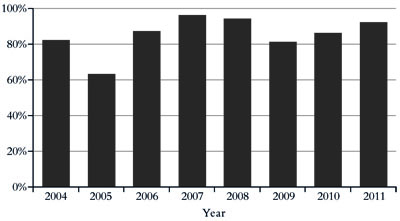

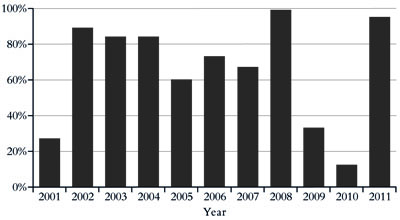

In fact, as figure one shows, the great majority of workers who have been on strike over recent years have been involved in strikes that have lasted for four days or less (or disputes that have involved four or less separate days of strike action). Most “working days lost” have also tended to result from strikes of four days or less (Figure 2). For both of these measures 2007 and 2009 stand out as exceptions (2009 extremely so)28.

Figure 1: Percentage of strikers involved in strikes of 1 to 4 days

Source: ONS

Figure 2: Percentage of working days lost in strikes of 1 to 4 days

Source: ONS

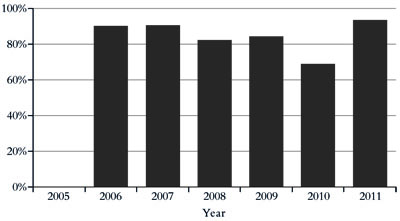

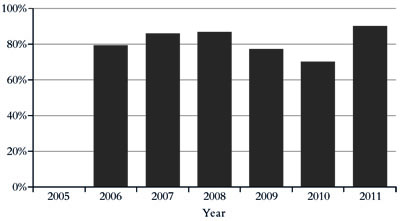

The ONS statistics also show that, measured in terms of strike participation and “working days lost”, large strikes have been the norm. Most workers who have taken strike action have been involved in disputes in which more than 50,000 working days were “lost” (Figure 3). Similarly, by far the largest proportion of “working days lost” in the total figures resulted from specific disputes in which 50,000 or more working days were “lost” (Figure 4). For both of these measures 2005 stands out as an extreme exception.

Figure 3: Percentage of strikers involved in strikes of 50,000 or more working days lost

Source: ONS

Figure 4: Percentage of working days lost (total) to strikes of more than 50,000 WDL each

Source: ONS

Public sector strikes have also been predominant for many years with the proportion of working days lost to this type of strike dropping below 80 percent of “working days lost” just once in the eight years leading up to 2011. Some caution is needed here for interpretation. When numbers of stoppages are used to compare public sector and private sector strikes a more even balance appears over recent years. Nonetheless, in terms of the “working days lost” and the numbers of workers involved, it is clear that public sector strike action is the dominant pattern. It is public sector strike action then that is also most likely to create the greatest social impact resulting from the experience of workers taking part.

Figure 5: Percentage of working days lost in public sector strikes

Source: ONS

Finally, the figures for the cause of strikes reveal that pay has featured prominently. Here the pattern has varied across recent years. For example, in 2009 and 2010 this was not the case with most strikes in these years being caused by redundancy situations. Still, the frequency of disputes over pay has been high and we have to go back to 2001 to find clearly localised issues such as “working conditions” appearing significantly in the statistics.

Figure 6: Percentage of working days lost to strikes over pay

Source: ONS

It is clear then that the most common form of strike action in the UK over the years leading up to N30 (and today) has been the one-day public sector pay strike—and N30 was the high water mark of this phenomenon. This is important to grasp in order to address our key concern: the relationship between rank and file members of the trade unions and their official leaderships.

Intrinsically, the organisational dynamics of the day of action are national. In this type of strike, unlike specifically workplace-based strikes that do tend more towards rank and file branch control and sometimes of an unofficial form,29 all of the levers of control remain within the hands of national officials and their regional offices. Moreover, these types of dispute typically occur following a breakdown of annual national pay bargaining and are called by the officials in response to reports from national negotiators. Lasting just one day, they do not allow local dynamics of any significance to emerge. Crucially, they render local leaderships reliant upon national decisions regarding the action in all of its major aspects. Over time the result is a relationship of rank and file dependence on the strategic direction set out by the national trade union bureaucracy. It is the reason that the national control of the bureaucracy over the movement following N30 was never in doubt and was the reason ultimately for the debacle.

Sean in his article argues that N30 was not simply a bureaucratic mass strike. I argue here that it was a bureaucratic mass strike in all of its dominant features. To borrow again from Cliff’s analysis, if the 1926 General Strike was a bureaucratic mass strike, then N30 certainly was. However, Sean is also formally correct. It was not simply a bureaucratic mass strike; but then neither was the 1926 General Strike. Indeed no mass strike is ever simply bureaucratic. Each has its own specific dynamic shaped by a range of factors: industrial composition; political influences; geography; the behaviour of the state, etc. There is also always some level of rank and file activity and even initiative present. Indeed it is precisely this concrete and specific detail that needs to be understood for an effective orientation in relation to any particular mass strike and during a period in which this type of industrial action represents a norm. We can approach N30 in this way to describe the opportunities it did create for local activists and to assess what these might mean more generally with regard to perspectives for trade union work.

N30 and the local left

There is no question that N30 presented the activist left with significant opportunities to influence events to some degree in each town and city as well as to extend and deepen its networks. In the following discussion some of these will be described and illustrated by reference to the experience of one small network of activists in Liverpool in shaping some aspects of the day in the city.

In the weeks leading up to the pensions strike day an invitation had gone out from UCU activists to those in other unions preparing to strike. The call was clear that this was not intended to be a coordinating centre and made no pretence of being formally representative. The work of other existing local bodies such as the Liverpool Trades Union Council, for example, was acknowledged. The message was that if activists wished to meet up to share experiences and ideas then the local UCU offices would be available for that purpose. In the six weeks ahead of the strike three meetings took place. These meetings varied in attendance between five and 11 workplace activists, union reps and city-wide union officers. Across these meetings 18 people were involved, between them representing UCU, NUT, Unison, PCS and the trades council.

The ideas from these meetings were later taken to one official organising meeting held in the offices of the PCS. For the preparations for N30 the TUC had delegated organising responsibility and budgets to different unions in different regions. This did affect the ability of workplace-based trade union activists to access key strategic meetings in that the regional offices of different unions had quite different attitudes to their local lefts. In Liverpool activists were fortunate in that a left controlled union, the PCS, had been tasked with this role. The key figures within the regional office of the PCS were quite open to the officers of local union branches becoming involved in some aspects of the planning. This was not the case in every part of the country and where right dominated unions had been given this organising responsibility activists found more obstacles in their way.

Three ideas were fed into the planning process in Liverpool that made a difference on the day: the organising of a battle bus; the involvement of students; and service-group meetings for strikers following the main rally.30 The battle bus was a popular idea and went ahead without any difficulty. On the day it set off from the university quarter staffed by students, university strikers and the “Socialist Singers”31 to tour all of the main picketing areas across Bootle, Liverpool and Speke. There was some discussion about the proposal to welcome students onto the day’s events. However, again this was brief and no serious opposition was raised. Students were prominent on the day especially on university picket lines. One important effect of this argument being pushed was that the President of the Liverpool Guild of Students spoke at the main rally, making the most radical (and memorable) speech of the day.

Finally, of the service-group strikers’ meetings that had been proposed it was the education workers’ meeting that actually went ahead. This was the result of a good working relationship that had been quickly established between local branch officers of the UCU and the NUT. For the day a large room in a pub near to the main rally point was booked. The pub had been persuaded to subsidise their food menu. The room was set up for an open-mic event and 5,000 leaflets were produced advertising an opportunity to meet as education workers after the main event, to rest and to assess the day’s experience. On university picket lines activists were asked to hand out the UCU’s share of the leaflets to picketers and later on the march. Around 200 education workers came to this meeting. The composition was mainly NUT but with a good presence from the UCU and a small group of NASUWT members. For an hour speakers from these different unions gave reports of their picket-line experience and campaigns of various kinds including a fight against an academy and one anti-victimisation struggle. A DVD of the anti-academy campaign was shown to finish the political part of the event. From then on rank and file activists and strikers from different unions mixed and talked informally about the day.

The account given here is intended only as an example of one local experience. In many areas and with variations of course, this kind of experience will have been fairly typical. More importantly, however, it provides an illustration of one kind of rank and file initiative that applies within the context of the bureaucratic mass strike. We can elaborate upon this theme in relation to the larger questions of what kind of rank and file activity local activists were engaged with on N30 and, importantly, how this type of activity fits into our wider understanding of how a strengthened and less dependent culture of rank and file activism and leadership might emerge.

Building the rank and file in history and today

Forms of rank and file organisation and their purpose

Steve Jefferys identifies three historical forms of rank and file organisation in Britain.32 Firstly, there is the shop stewards committee that reflects a specific work group and that has bargaining power with management. This form is “spontaneous” in that it arises from the structure and patterning of the work process itself. It is seen as “legitimate” by all workers in that group, regardless of politics or militancy. The second type is that of the combine committee that organises across a company or industry representing a range of occupational groups. This type also reflects industrial composition but at one level removed from immediate production processes. The third type is that of the rank and file movement that is consciously built by a militant minority across workplaces and industries.

This latter type is not recognised by managements and is not formally representative. It has no negotiating position and does not normally command influence among a majority of workers. Before 1928 for example, the Communist-led National Minority Movement (NMM) had drawn Communists together with workers who were members of the Labour Party and the Independent Labour Party as well as independent militants, in various worker actions. The model for the NMM, explicitly stated at its launch conference in August 1924, was that of the factory committees that had been built during the war by the Shop Stewards and Workers’ Control Movement (SSWCM) in the engineering plants especially in Sheffield and on the Clyde.33 In 1928, however, the Communist Party leadership, following Stalin’s Third Period policy, threw its members into a sectarian stance against reformist organisations, putting many of its best militants at odds with reformist workers in workplaces. By 1932, after four years of this disastrous strategy, many Communist workers were to return to their earlier efforts to build a rank and file movement of industrial militants.

This typology is useful not only in illuminating the differences of organisational form but also in clarifying differences of purpose. The first two forms described by Jefferys can certainly play the role of coordinating industrial action as did the British Motor Corporation Combine Committee magnificently in 1972. However, such workplace and industry-based formations can also serve a regulating function in bargaining with employers and playing the role of de facto mediator between workers and managers in daily work processes. During the First World War, for example, the huge adjustments to industry could not have been achieved without this type of workshop organisation and an incorporated layer of worker representatives.34 Indeed during the 1960s workplace bureaucratism represented an “insidious trend” that alienated workers from their shop stewards as well as the trade union officials.35 Short of such collaborationist tendencies, however, often unconscious in the individuals that embody them, there are differences of intention within different forms of rank and file organisation. In the cases of the NMM and the SSWCM the aim had been that of worker actions that were independent of the trade union officials. This contrasted with the orientation of the miners’ United Reform Committee (URC) some years earlier and before the First World War, the aim of which was to work as a ginger group exerting pressure upon the officials to act.36 This “gingering” role was also the position adopted by the Communist Party during the days of the 1926 General Strike.37

In the years following the Second World War and under its British Road to Socialism programme, the Communist Party had come to see in the shop stewards committees a lever by which to tip the balance of forces towards the working class as part of its political strategy. The orientation then had been on capturing the trade union machine, position by position, with candidates of the left, whether Communist Party or Communist-aligned. The result was that by the early 1970s the Communist Party, through its industrial front, the Liaison Committee for the Defence of Trade Unions (LCTDU), had achieved significant mobilising power. Despite this, however, in the major battles with the Ted Heath government following the introduction of the 1971 Industrial Relations Act the LCDTU made no effort to link rank and file militants together:38 that was never its purpose.

The challenge today: One perspective

The paradox faced by Marxists in the unions today is that of the mass strike that brings tens and hundreds of thousands out on strike but in a form that fosters dependence on the national officials. There is broad agreement about the great potential that exists for independent working class action. It is also not disputed that the “lefts” have been instrumental at key moments in the internal machinations of their various unions and that this has led to days of action where they might not otherwise have happened (though the predominant pressure on the trade union bureaucracy to act has come from the assault by the state). It is also true that the effect of N30 combined with the work of left members of some of the key unions (notably within UCU, NUT, NASUWT and PCS) meant that genuine struggles took place inside those unions resulting in further days of action on 28 March and 10 May 2012 before the coordinated character of the pensions fight finally collapsed.39 The battle between left and right in the unions is clearly of real consequence.

What is in question, however, is how the working class can advance its struggle beyond actions that are sanctioned by their leaderships and that, more frequently than not, fail. To answer this we need more than a strategy of sophisticated internal operation and appeals to the “mood of the class”. This is not the same as an argument that there are “too many comrades on the national executive”. It is not fundamentally a quantitative matter: rather it is one of orientation. Along with the work of leading activists at the regional and national strategic levels there must be, as its complement, a properly developed focus on the structure of the rank and file opportunities that present themselves.

Without this kind of systematic attention the dependency created by the current contradictions of the working class movement becomes reproduced structurally within the trade union lefts themselves, with national level activists becoming the “experts”, always reporting specialist knowledge from within the union machine. Moreover, this strategic focus needs to combine an attention to the concrete detail and nuances of specific and local rank and file “moments” that occur—and to which the individual activist can relate—with an anticipation of sudden and large-scale shifts within the working class. For this latter perspective an ability to break with the established trade union lefts is also important. This was demonstrated at national level by the example of the Jerry Hicks campaign inside the Unite union in early 2013.40 But it is with the local that we will end this discussion and by way of a return to our earlier considerations of the mass strike.

In his survey of the pattern of specific strikes leading up to the French May 1968 general strike, Cliff describes how these served as rehearsals for “the great event”.41 These rehearsals included one-day strikes against the new social security measures introduced by the French government in October 1967. The pattern was different than the one we face in the UK today. The build up to May ‘68 involved intense factory struggles and violent confrontations with the CRS corps of the French state. Still, the theme of rehearsals is useful here in reaching a conclusion. Each one-day public sector strike is indeed potentially a rehearsal for “great events”; but each needs to be treated as such. Called and controlled by national officials, one-day strikes nonetheless create opportunities for local initiatives and actions that can begin to build the independent confidence of workers locally. But this means attention to small steps as well as strategic work inside the union machine.

In Liverpool the effects achieved by the intervention of one small ad hoc grouping of union activists were modest in relation to the day’s main events of pickets all across the city and a demonstration of 20,000. Indeed, the term “ginger group” is probably the one that applies best. Putting on a battle bus and encouraging students to become involved certainly helped to liven up the day. The education workers’ meeting was important in that it was a thoroughly rank and file affair and enabled strikers to report their experiences and views spontaneously, with no major preparation and in the absence of the platform of officials—of the left or the right. Again this did not have an impact on events in any major sense. But it did push beyond the official plans for the day. It is in that sense that such opportunities, if seized, are preparations for whatever is on the horizon.

The national trade union bureaucracy will call one-day strikes in this period. The threat they face to their organisational bases is too profound and their members are too angry for them not to do so. Official lefts will play important, and at points decisive, roles in advancing those actions. However, in the workplace left activists need to know that what they do locally in deepening their own roots, liaising with others in workplaces in their vicinities is in the end what will decide whether workers are able to act independently of the strangulating hold of the trade union bureaucracy. The organisational expression that this takes is likely to vary from area to area and to evolve over time.

Today we talk of “networks” and this seems realistic. In fact, the form of networks themselves can vary greatly from those that have clearly defined memberships and with established leaderships that meet regularly, to far more diffuse formations that come in and out of active focus and that are based on loose affiliations and personal activist relationships stretching back over years. Whatever organisational form they take, however, rather than being formally representative, patterned by trade union structures and seen as legitimate by all workers, they will need to be based upon militant minorities, be action-oriented and able to lead layers beyond them. If properly positioned they will also, at crucial stages, be of decisive effect for the direction of large-scale struggles.

We have a sense today of growing anger and potential volatility across many parts of the British working class. Their highest expression in terms of scale so far is the public sector mass strike. The bureaucratic control of this phenomenon, however, raises the frightening prospect of a collapse into battle weariness on the part of activists and cynicism across trade union memberships. Any such collapse will enable national official leaderships further to strengthen their control, so creating a downward spiral. Each national action, however, presents a new opportunity—a potential rehearsal—to local activists, individually and in small groups, to take initiatives to forge new activist links, to make networks more systematic, to raise confidence and so on. Between action that is official and relatively passive and action that is unofficial and dynamic there are actions that, while occurring within the domain of “the official”, can be nonetheless relatively independent. These actions can push against official restrictions and strain towards more thoroughgoing rank and file independence.

By adjusting our lens upon this area of possible strategy (and risk) we can prepare for the opportunities for independent rank and file action that will appear in the coming years. This type of work, properly understood and encouraged, will lead to more solid forms of rank and file organisation as well as a growing consensus among workplace activists that this is what is needed. By creating a sense of steps forward it will also make the official one-day strike a rehearsal at every level including that of the individual activist in the workplace—no matter how isolated they may have been previously. What is of ultimate importance is the ability of the local activist to translate the national strike into stronger and more activist-oriented local organisation and in ways that engender rank and file independence. This may appear in the short term to be a strategy of small steps forward in anticipation of “great events”. However, our attitude must surely be that no step, taken firmly towards your goal, is too small. After all, this (and not national positions) is what will make the difference in the end.

Notes

1: Vernell, 2013.

2: Cliff and Gluckstein, 1986, p22.

3: Lenin, 1974, pp438-454, referred to by Cliff and Gluckstein, 1986, p23.

4: Cliff and Gluckstein, 1986, p22.

5: Cliff and Gluckstein, 1986, p17.

6: Cliff, 1961, pp10-17.

7: Harman, 1985.

8: Cliff, 1959. Cliff cites two articles by Luxemburg: “The Belgian Experiment”, Die Neue Zeit, 26 April 1902, and “Yet a Third Time on the Belgian Experiment”, Die Neue Zeit, 14 May 1902.

9: Trotsky, 1935.

10: These events were analysed in detail by Xavier Mourre, 1961.

11: Cliff, 1961, p15.

12: Cliff, 1985.

13: Cliff and Gluckstein, 1986.

14: McFarlane, 1966, p173, cited by Cliff, 1985.

15: Cliff, 1985, p23.

16: Cliff, 1985, p44.

17: Cliff, 1985, p48.

18: As Cliff explains, this figure is an estimate as political strike days are not recorded.

19: Cliff, 1985, p21.

20: Kimber, 2012.

21: Welsh teachers.

22: First Division Association: Senior civil servants.

23: Probation officers.

24: Kimber, 2012.

25: Kimber, 2012.

26: According to a BBC poll 66 percent said that the strikes were justified. Among 18 to 24 year olds the figure from this poll was 79 percent-Kimber, 2012.

27: All of the strike figures used here are compiled from the ONS Labour Disputes annual articles and labour disputes reports for the years 2006 to 2011 inclusive (ONS, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2012a and 2012b). The limitations to the ONS statistics are acknowledged in the technical notes to the articles: the figures do not include political strikes; they do not distinguish between official and unofficial strikes; short stoppages involving small numbers of workers that are not widely reported can be missed; etc.

28: 2009 also had the lowest number of work stoppages in over 50 years.

29: A feature noted by Kimber, 2009.

30: Strikers had been organised into four occupational service-groups for the march.

31: A Liverpool based socialist choir that has become a familiar feature of university strike days.

32: Jefferys, 1980, p25.

33: Callinicos, 1982, p11.

34: Cole, 1923, pp3-4. Cited by Hyman, 1980, p36.

35: Cliff, 1970, p204. Cited in Hallas, 1980, p46.

36: Cliff and Gluckstein, 1986, p48.

37: Cliff and Gluckstein, 1986, p50.

38: An observation made by Callinicos, 1982, p22.

39: Miles, 2012.

40: Jerry Hicks was the independent “fighting” candidate for the position of Unite General Secretary 2013. His candidature was the cause of a split of the Unite left grouping with Socialist Worker Party activists breaking from it to support Hicks’s campaign. He won an extraordinary 80,000 votes, 36 percent of the turnout.

41: Cliff, 1985.

References

Callinicos, Alex, 1982, “The Rank-and-File Movement Today”, International Socialism 17 (autumn), www.marxists.org/history/etol/writers/callinicos/1982/xx/rfmvmt.html

Cliff, Tony, 1959, Rosa Luxemburg (International Socialism pamphlet), www.marxists.org/archive/cliff/works/1959/rosalux/

Cliff, Tony, 1961, “Belgium: Strike to Revolution”, International Socialism 4 (1st series)(spring) www.marxists.org/archive/cliff/works/1961/xx/belgium.htm.

Cliff, Tony, 1970, The Employers’ Offensive: Productivity Deals and How to Fight Them (Pluto),

www.marxists.org/archive/cliff/works/1970/offensive/index.htm

Cliff, Tony, 1985, “Patterns of Mass Strike”, International Socialism 29 (summer), www.marxists.org/archive/cliff/works/1985/patterns/

Cliff, Tony, and Donny Gluckstein, 1986, Marxism and Trade Union Struggle: The General Strike of 1926 (Bookmarks).

Cole, G D H, 1923, Workshop Organisation (Clarendon).

Hallas, Duncan, 1980, “Trade Unionists and Revolution—A Response to Richard Hyman, International Socialism 8 (spring), www.marxists.org/archive/hallas/works/1980/xx/turev.html

Harman, Chris, 1985, “What do we Mean by the General Strike”, Socialist Worker Review (April), www.marxists.org/archive/harman/1985/01/genstrike.htm

Hyman, Richard, 1980, “British Trade Unionism: Post-war Trends and Future Prospects”, International Socialism 8 (spring), www.marxists.org/history/etol/newspape/isj2/1980/no2-008/hyman.html

Jefferys, Steve, 1980, “The Communist Party and the Rank and File”, International Socialism 10 (autumn), www.marxists.org/history/etol/writers/jefferys/1980/xx/cp-rf.html

Kimber, Charlie, 2009, “In the Balance: the Class Struggle in Britain”, International Socialism 123 (spring), www.isj.org.uk/?id=529

Kimber, Charlie, 2012, “The Rebirth of our Power? After the 30 November Mass Strike”, International Socialism 133 (winter), www.isj.org.uk/?id=774

Lenin, V I, 1974 [1915], “Opportunism, and the Collapse of the Second International”, in Lenin Collected Works, Volume 21 (Progress Publishers, Moscow).

McFarlane, Leslie J, 1966, The British Communist Party. Its Origins and Development Until 1929 (MacGibbon and Kee).

Miles, Laura, 2012, “Stepping Up the Pressure on Pensions”, New Left Project, www.newleftproject.org/index.php/site/article_comments/stepping_up_the_pressure_on_pensions

Mourre, Xavier, 1961, “Belgium: Success Beyond Our Grasp”, Internationalism Socialism 4

(1st series) (spring), www.marxists.org/history/etol/newspape/isj/1961/no004/mourre.htm

Office for National Statistics, 2007, “Labour Disputes in 2006”, Economic and Labour Market Review, Volume 1, Number 6 (June).

Office for National Statistics, 2008, “Labour Disputes in 2007”, Economic and Labour Market Review, Volume 2, Number 6 (June).

Office for National Statistics, 2009, “Labour Disputes in 2008”, Economic and Labour Market Review, Volume 3, Number 6 (June).

Office for National Statistics, 2010, “Labour Disputes in 2009”, Economic and Labour Market Review, Volume 4, Number 6 (June).

Office for National Statistics, 2012a, Labour Disputes: Annual Article, 2010 (1 August),

www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/bus-register/labour-disputes/annual-article-2010/index.html

Office for National Statistics, 2012b, Labour Disputes: Annual Article, 2011 (15 August),

www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/bus-register/labour-disputes/annual-article-2011/index.html

Trotsky, Leon, 1935, “The ILP and the Fourth International: In the Middle of the Road”,

www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1935/09/ilp-fi.htm

Vernell, Sean, 2013, “The Working Class, the Trade Unions and the Left: the Contours of Resistance”, International Socialism 140 (autumn), www.isj.org.uk/?id=930